The inclusion of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area in China’s national strategies, such as its 13th Five-Year Plan and Vision and Actions on Jointly Building the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, will bring about new opportunities for the development of Hong Kong in the years to come. In this connection, action should be taken as soon as possible to map out plans taking advantage of Hong Kong’s strengths in financial services, professional services and international ties in order to enhance co-operation with Guangdong as well as to explore new horizons and add new vitality to the sustainable growth and prosperity of Hong Kong.

Hong Kong’s strengths in financial services, professional services and international ties can also contribute to the transformation and upgrading of industries in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area, building the Bay Area into a world-class city cluster with international competitiveness as well as a leading economic growth engine for the mainland, driving the development advantages of the Pan-Pearl River Delta (PRD) region encompassing central-south and southwestern China. The Bay Area will also play an important role in building the Belt and Road. With reference to other economically advanced bay areas in the world and analysing the development of Hong Kong and the PRD, the following initial thoughts regarding the future industrial and trade development of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area and the roles played by Hong Kong may serve as the reference for further discussion.

Development Advantages of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area

1. Transportation and Logistics

As a collective economy, the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area is home to a number of leading airports and ports in the PRD region, with air and sea cargo throughput ranking first not only in China but also in the world. The PRD, covered by an extensive network of railways and highways with the Bay Area as the core, offers multimodal transport both internally and externally conducive to logistics development.

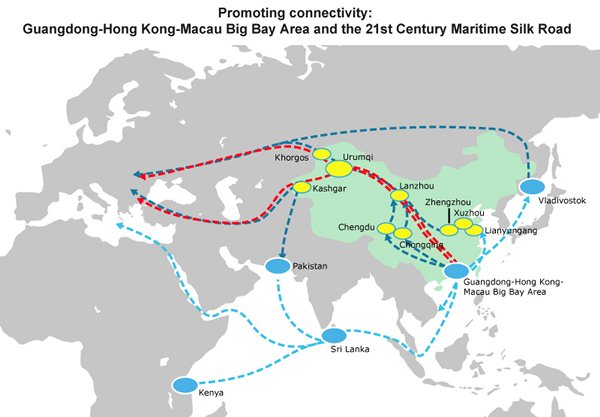

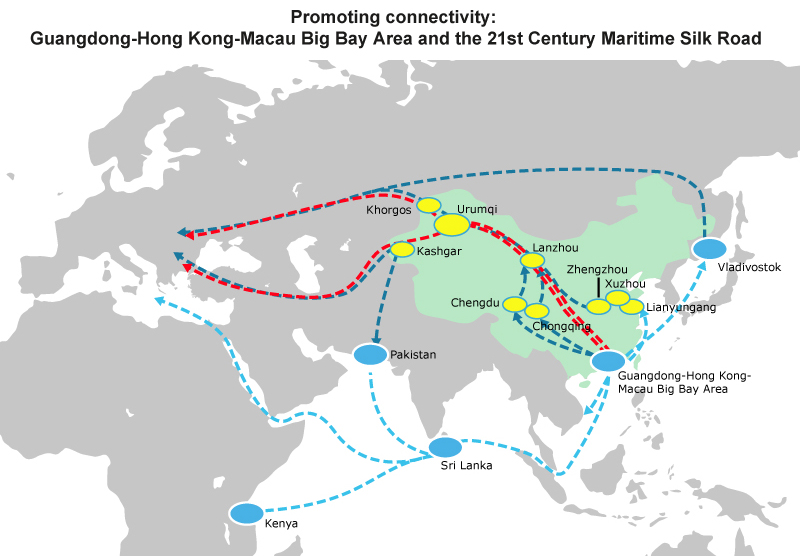

Compared with other regions in the Chinese mainland and overseas, the Bay Area, as a major passageway for air, land and sea transport linking countries along the Belt and Road, has obvious advantages in terms of geographical location and logistics infrastructure.

2. Upstream and Downstream Industry Supply Chain

Among all provinces and cities in China, Guangdong ranks first in terms of industrial value-added and export, while the PRD accounts for 80% of the industrial value-added and 95% of export for the province. Despite rising production costs in the PRD in recent years, thanks to its strengths in logistics, industrial structure and comprehensive supporting facilities, the majority of enterprises in the region still opt to retain their production lines there while taking action to move towards automation and high value-added production. According to findings of a questionnaire survey conducted by HKTDC Research, 70% of the surveyed manufacturers and traders still see the PRD as the most important production or sourcing base, with 81% sourcing raw materials and semi-manufactures in the PRD for production activities. Among companies which have plans to expand or relocate their factories, 59% said they would still choose the PRD, while the rest mostly opt for other mainland regions close to the PRD or Southeast Asia. In fact, some enterprises which have already relocated to northern Vietnam pointed out that one of the advantages of investing there is its proximity to the supply chain in the PRD which helps to raise production efficiency and lower logistics cost.

3. ICT and High-tech Industry Cluster

Under China’s innovation-driven development strategy, a high-tech industrial belt has gradually taken shape in the PRD. The PRD High-tech Industrial Belt is one of the three national-level belts of its kind approved by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST). This belt covers six national high-tech industrial development zones in Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Foshan, Zhongshan, Zhuhai and Huizhou; three provincial high-tech industrial development zones in Dongguan, Zhaoqing and Jiangmen; two national software industrial bases in Guangzhou and Zhuhai; three national high-tech products export bases; 12 national '863' achievement transformation bases; and one national-level university technology park.

In 2015, the shares of advanced manufacturing industry and high-tech manufacturing industry amounted to 53.9% and 31.8% in PRD’s total value-added industrial output respectively; R&D spending as a share of GDP reached 2.7%; the number of applications for invention patents per 1 million people was 1,728; ownership of invention patents per 10,000 people was 23.33; and technology self-sufficiency rate was over 71%.

4. International Financial and Professional Services

Compared with other city clusters in the mainland, the PRD Bay Area has the unique advantage of encompassing Hong Kong, an international financial centre, in its ‘one-hour economic circle’. Hong Kong, with its large pool of professional service providers and international talent, as well as economic and judicial systems different to those of the mainland, is an ideal gateway for multinational companies entering the Asia and China market.

According to a survey conducted by the Hong Kong SAR government, as of June 2016 there were a total of 3,731 regional headquarters and regional offices in Hong Kong which represent their parent companies outside Hong Kong in handling their business in the Chinese mainland, Northeast Asia and Southeast Asia. As such, Hong Kong has been a leading region in the world for many years in attracting foreign direct investment and exporting outbound direct investment. Moreover, Hong Kong accounted for 52% of China’s cumulative utilised foreign investment as at the end of 2016 and about 60% of its cumulative foreign direct investment as at the end of 2015.

Development Prospects for Economic Integration of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area

Although the political and legal systems of Guangdong, Hong Kong, and Macau differ greatly, through existing co-operation frameworks between governments of the three places and co-operation platforms such as CEPA and free trade zones, trade between Guangdong and Hong Kong and between Guangdong and Macau is basically liberalised. Hong Kong and Macau already have plans to conduct negotiations on free trade agreement, which, when completed, will turn Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macau into one free trade zone.

In view of the fact that Hong Kong is a service platform for the mainland in its ‘bringing in’ and ‘going out’ strategies, players in the industry clusters in Guangdong and Hong Kong, including production enterprises, service suppliers, capital providers, universities and R&D centres, have already established close ties with one another and the two places have practically formed a collective economy. Connections between Guangdong and Hong Kong in terms of people flow, logistics, transportation, capital flow, commercial existence and corporate investment can well testify to this.

It can be expected that upon completion of the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge and Shenzhen-Zhongshan Bridge, transport links, customs clearance and trade activities at the Pearl River Estuary will be further enhanced. One of the objectives of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area plan is to further deepen co-operation in the Bay Area and co-ordinate the connectivity and construction of infrastructural projects, including ports, airports, railways and highways in Hong Kong, Macau and PRD cities.

Efforts should be made to expand the liberalisation of and co-operation in financial and services sectors; promote the free flow of factors of production, products, technology and services within the Bay Area; create an environment conducive to the transformation and upgrading of existing industry clusters and the growth of new industry clusters. Action should also be taken to attract more domestic and foreign investors, as well as trading and commercial activities to the Bay Area in a bid to create more room for development and business opportunities for cities in the area.

In the US, the San Francisco Bay Area (SFBA) comprises nine counties. While each county has its own characteristics and advantages, the rate of economic and industrial development and urbanisation of the entire SFBA is very high and interaction among the nine counties is extremely strong. Industry clusters in the sub-regions of the SFBA are similar, which mainly include industries taking advantage of local talent, such as professional services, scientific research and technical services, as well as tourism-related industries.

The majority of the industries with outstanding performance in the SFBA also have a presence in almost all the sub-regions. While the three largest and most important industry clusters in the SFBA established their foothold in the San Francisco and San Jose sub-regions, three-quarters of the sub-regions house at least two industry clusters which are developing well in the SFBA. Also, residents in the SFBA commute between different sub-regions every day and ties between all the sub-regions are close. This shows that the economic operation of the SFBA works as a collective whole.

The high degree of interaction between the sub-regions means that any development strategy which takes into consideration just one county or sub-region will miss out on benefits which can only be brought about by taking the entire bay area into account [1].

In a move to meet demands of the market and of their own development, PRD enterprises have started to establish their presence in more than one city. For instance, TCL Communication Technology Holdings Ltd has its production base in Huizhou and China headquarters in Shenzhen, while its Hong Kong office takes charge of overseas business. Another example is Welon (China) Ltd, which set up its base in Huizhou at first, but as business continued to expand the company began to build production lines for different sporting goods in various PRD cities and even set up its China headquarters and production R&D centre in Guangzhou. In order to better co-ordinate its expanding overseas business, Welon may consider setting up an office in Hong Kong.

It can be expected that PRD enterprises will increasingly carry out their business development according to the competitive advantages and economic environment of different cities in the Bay Area. This will in turn bolster the economic and industrial development as well as urbanisation rate of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area, while interaction between cities within the Bay Area will also grow stronger.

Hong Kong’s Role in the Future Development of the Bay Area

1. Global Supply Chain Management and Logistics Centre

In recent years, as production cost in China continues to climb, many enterprises have relocated or extended their production lines to emerging countries such as Vietnam and Bangladesh. As a result, a supply chain linking China, East Asia, Southeast Asia and South Asia has gradually been formed to become one of the world’s three largest regional supply chains on a par with the Americas and Europe.

Under the pressure of rising wages and labour shortage, many labour-intensive enterprises in the PRD, such as those engaged in garment and footwear manufacturing, have relocated their production lines to popular spots in Southeast Asia and South Asia. This has caused China’s share in the garment imports into the US and EU to drop from 39% and 42% respectively in 2012 to 36% and 34% respectively in 2016. During the same period, China’s share in the footwear imports into the US and EU also fell from 72% and 51% respectively in 2012 to 58% and 45%.

However, it is interesting to note that the share of Chinese goods in total imports into the US and EU actually rose rather than dropped, while China’s share in global industrial products exports jumped from 16.8% in 2012 to 18.6% in 2015. This shows that China’s manufacturing industry and exports are gradually moving towards high value-added and upstream products.

According to data released by the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the share of China’s semi-manufactures exports in the world rose from 9.6% in 2010 to 12% in 2014. A large part of this was exported to Southeast Asia and South Asia, which reflects the increasingly close supply chain relationships between countries in these regions and China. Currently, the PRD is the ‘world factory’ for a wide range of consumer goods and intermediate products. As Chinese enterprises and other multinational corporations expand their processing and production activities in Southeast Asia and South Asia, they have to import various parts, components, accessories and industrial materials produced in other countries, as well as those produced by their factories in the PRD and their upstream suppliers.

Since the industrial base of emerging markets in Southeast Asia and South Asia is still in its nascent stage, if local and foreign invested enterprises wish to expand their production in these countries, they must import more advanced processes. And in so doing, they have to seek the support of foreign professionals and services, including a wide range of engineering, equipment manufacturing and environmental services.

Hong Kong is an international commercial and logistics centre in Asia, its service suppliers possess rich professional knowledge and have established extensive business networks in many countries and regions, hence, it can help China connect with other regions by providing one-stop services in supply chain management, including the above mentioned production, logistics and environmental services.

In addition to building a supply chain for processing and production activities, the rapid development of logistics supply chain services is not to be overlooked as the booming Chinese economy and other emerging Asian countries has pushed up the income level of the population, which in turn has generated great demand for imported consumer products.

In particular, as e-commerce has grown in leaps and bounds in recent years, the way of doing business has undergone immense changes. And as consumer products are moving faster and faster, the demand for high-efficiency international supply chain services is also bound to expand further. Judging from the structure and growth of Hong Kong’s re-export trade currently, the role played by its logistics sector is becoming increasingly important in Asia’s regional supply chain.

Capitalising on the service networks and efficiency of the airports and ports of Hong Kong, Shenzhen and Guangzhou, as well as the close co-operation between the Guangdong and Hong Kong customs and port authorities (such as the new logistics services offered by the one-stop air-land multimodal super trunk line in Hong Kong Airport and Nansha Bonded Port Area Logistics Park), the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area can be expected to maintain its position and competitiveness as a logistics hub in the course of its development as a supply chain linking major regions around the world and as a regional supply chain serving China in its move to connect with Asia.

Within the Bay Area there are five airports, namely in Hong Kong, Macau, Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Zhuhai, while Hong Kong, Guangzhou and Shenzhen also have their own international ports. How to co-ordinate these facilities and pursue rational development, complementariness and co-operation in order to strengthen the competitiveness of the Bay Area will have to depend on the communication and collaboration between the participating members.

In the case of Japan’s Tokyo Bay, there are six ports, namely in Tokyo, Yokohama, Yokosuka, Kawasaki, Chiba and Kisarazu. In order to avoid vicious competition, these ports were carefully planned with the aim of promoting co-ordinated division of labour and co-operation. Each port performs different functions according to its strengths and characteristics and all six synergise to form a port cluster.

The planning and development of infrastructural facilities such as ports and airports in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area can refer to the Tokyo Bay model in achieving co-ordinated division of labour and complementariness. For instance, Hong Kong, as an international aviation hub, has a strong network of international air routes (for both passenger and cargo flights).

Through strengthening water and land transport links with Shenzhen’s airport and ports as well as customs co-operation, Hong Kong can provide multimodal transport services linking mainland cities with foreign markets. Also, upon completion of the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge, Zhuhai Airport can forge closer co-operation ties with Hong Kong Airport and further strengthen the competitiveness of the Bay Area as an international logistics hub.

Where promoting logistics resources integration and complementariness in the Bay Area is concerned, Guangdong and Hong Kong can further enhance collaboration in a move to raise the level of advanced and highly efficient services such as online logistics, customs clearance, payment, source tracing and tracking in international trade.

2. Advanced Production and Innovation R&D Centre

Technology and innovation are the main direction for future development. In the course of building the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area into a city cluster with global influence and competitiveness, technology and innovation are important drivers. Technological development not only aims to enhance the R&D capability of the Bay Area, but also extensively apply technology in different areas, such as smart production, smart cities, Internet of Things, environmental protection and energy saving, in order to raise the level of overall economic efficiency and sustainable development. Industrial development in the PRD region can also attract more input into R&D and propel a benign cycle.

Information on Guangdong’s planning shows that the PRD will, leveraging on its industrial advantages, build five high-tech industry clusters:

(a) Using Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Foshan as the fulcrum to drive development of the information industry in cities including Zhuhai and Zhaoqing, and to expedite the pace of building a national-level information industry base in the PRD.

(b) Using Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Dongguan and Huizhou as the fulcrum to create a number of new energy industry clusters and establish a new energy car production base; using Shenzhen, Dongguan, Foshan and Zhongshan as the fulcrum to build a national solar photovoltaic high-tech industrial base to support the development of low-carbon economy in Shenzhen, Jiangmen and Zhaoqing, and to accelerate the pace of Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Foshan and Dongguan in creating a national-level new energy, environmental protection and energy saving industrial base.

(c) Using the Torch Plan new materials and niche industry base and the national high-tech industrial base for new materials in Guangzhou and Foshan as the pillar to create a leading national-level new materials industry base.

(d) Using the two national biological industry bases in Guangzhou and Shenzhen as well as Zhongshan as the support to create a national bio-medicine and leading modern innovation industry base.

(e) Using Guangzhou and Shenzhen as the core to develop a world-class LED new light source industry integrating Shenzhen, Dongguan, Huizhou, Guangzhou, Foshan, Zhongshan and Jiangmen, and to form an LED new light source upstream-downstream integration industrial belt in the PRD.

Unlike the San Francisco Bay Area in the US whose industrial structure focuses on professional/scientific and technical services as well as the information industry, the industrial structure of the PRD covers a wide spectrum of industries ranging from high-tech to a diversity of traditional manufacturing.

While technology can be applied in different sectors and smart cities, internet of things, environmental protection and energy saving are major directions. How to promote the integration of advanced technology, modern professional services and traditional industries in order to accelerate industrial transformation and upgrading in the Bay Area is a development direction that warrants attention. For instance, manufacturing industry production lines in the PRD should move towards automation, while industrial associations in various cities in the Bay Area should strengthen exchanges and co-operation, combine different industrial enhancement resources and technological resources, and develop automation equipment suitable for their respective industries.

Today, mainland enterprises boast sound R&D ability and have developed a wide range of popular technologies and products in such areas as ICT applications and solutions as well as mobile device applications (apps). However, not many enterprises manage to extend such technological applications from local level to national level, neither can they tap the international market by using technologies that meet international standards. Meanwhile, although China is still at a nascent stage in certain advanced technologies, it is finding it difficult to import foreign technologies directly into the mainland for application due to different technical specifications and user experiences.

Compared with the mainland, Hong Kong is weaker in terms of scientific research input and overall R&D capability. However, Hong Kong companies are not only well-versed in international technological trends and technical standards, but also have established extensive international market networks. As such, Hong Kong can collaborate with Shenzhen as well as cities within the Bay Area in forging closer ties in personnel exchange, technological application, and technical specifications in relevant technological sectors.

Such joint efforts not only can help advance commercialisation of mainland technological achievements and develop overseas markets, but also effectively bring in the right foreign technologies for mainland industry players for local application, which will in turn boost the overall development of the Bay Area.

In certain high-tech industries, e.g. internet of things applications and development of next generation internet, some mainland enterprises currently still lack the necessary expertise, which has more or less restricted the relevant R&D and technological application. Hong Kong’s technological industry players have good knowledge about advanced foreign technologies, excel in using technologies developed in accordance with international standards/frameworks, and are experienced in importing foreign technologies. Therefore, they can help mainland projects pursue commercialisation to meet market demand.

Hong Kong, as a regional intellectual property trading hub, offers sound protection to intellectual property and provides excellent professional services. Hence, the SAR has attracted a great number of technology, creative, R&D, design and production companies around the world to use it as a platform for trading intellectual property with the Chinese mainland and other Asian markets.

To meet the demands arising from the development of technology and innovation in the Bay Area, Hong Kong can give full play to its advantages as an intellectual property trading hub to bring in intellectual property, such as technology from abroad, as well as assist the Bay Area in launching its R&D achievements onto the market and tap the international market.

Financial technology is another sector where Hong Kong can participate in the technological and innovation development of the Bay Area. In Guangdong’s 13th Five-Year Plan, it was put forward that efforts would be made to encourage Shenzhen and Hong Kong to jointly build a global financial centre.

Hong Kong is already an international financial centre in its own right. As its ties with the mainland financial sector become increasingly close, it provides a sound co-operation base and excellent opportunities for the development of financial technology. For instance, for financial technology companies wishing to develop financial technology for stock investment, Hong Kong offers room for growth because its stock market has connections with both the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets.

Any enterprise wishing to engage in financial technology must possess knowledge in financial services and the necessary technical background. Hong Kong is not only home to a large pool of professionals rich in financial experiences and knowledge, but also has in place transparent regulations and a sound supervision system which guarantees information safety. As such, it can join hands with the technical personnel of the Bay Area in developing the right financial technology.

If Guangdong and Hong Kong can coordinate the development and application of financial technology in the Bay Area, including system standards and connection, the application and research of financial technology in the Bay Area is bound to reach an advanced level.

It can be expected that more and more entrepreneurs and investors in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area will be encouraged to participate in various technological innovation enterprises. Apart from demand for financial resources, these enterprises are also in dire need of supporting services in technology, market network and corporate development.

Technological innovation enterprises in Shenzhen and in the Bay Area at large can capitalise on Hong Kong’s advantages, such as the free flow of information and capital, extensive international market networks, and sound corporate management, to enhance their development ability. In encouraging Shenzhen and Hong Kong to jointly build an innovation platform, efforts have to be made to strengthen exchanges and connections between the R&D institutions and technological enterprises in the two cities in a bid to create a technological co-operation platform. Steps should also be taken to extend the platform to other related financial and professional services in the hope of combining each other’s advantages.

Pooling talent is an important factor in propelling technology and innovation. In attracting experts, especially experts from overseas, Hong Kong can join hands with Shenzhen and play to their respective strengths.

Foreign experts may find it easier to adapt to living in Hong Kong, an international metropolis, than in mainland cities. So, in order to attract foreign professionals to form R&D teams with mainland and Hong Kong personnel, action can be taken to form teams straddling Hong Kong and neighbouring Shenzhen. In so doing, foreign professionals can live in Hong Kong, where the environment is international, while maintaining close contacts with research team mates in the PRD region, in particular Shenzhen.

Hong Kong, with its foreign ties and international background, can be positioned as a base for foreign technological exchanges and co-operation in the Bay Area. Currently, Hong Kong and Shenzhen are planning to jointly build a Hong Kong/Shenzhen Innovation and Technology Park in the Lok Ma Chau Loop. Upon completion, this park can play a leading and demonstrative role in attracting the entry of mainland and leading foreign enterprises, universities and R&D institutions and help bolster the future development of the Bay Area.

3. Building the Belt and Road

Under the Belt and Road Initiative there are five development priorities: policy coordination, facilities connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration, and people-to-people bonds. Among the five, facilities connectivity takes the lead in driving the development of infrastructural projects.

According to the latest estimate released by the Asia Development Bank, from 2016 to 2030, in developing Asia alone, capital required for investing in infrastructural construction amounts to US$1.7 trillion a year. Currently, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are the major players participating in infrastructural projects along the Belt and Road. However, the diverse range of infrastructural construction projects along the Belt and Road require enormous amounts of investment.

The capital, risks, and management technology involved are far beyond the ability of the government and SOEs. Public-private partnership (PPP), which supplies the above investment essentials and brings in different innovative ideas, is crucial to the successful building of the Belt and Road.

The arrangement of PPP projects can be very complex as they involve investors from different countries and each of the multiple investing parties has its own interests in mind. Hong Kong companies have rich experience in PPP projects and Hong Kong, as an international hub, can play the role of a ‘super-connector’ in effectively matching participants in the projects and providing financing solutions.

Guangdong province has long been a major source of investment in China’s overseas contracted projects. Mainland enterprises, in particular Guangdong enterprises, have an edge in contracted projects, while Hong Kong’s professional and commercial services are highly rated in specific areas. For instance, many architectural, surveying and engineering services companies in Hong Kong have reached the world’s top levels. They can provide Guangdong enterprises participating in Belt and Road infrastructural projects with a wide range of services, such as consultancy, design, planning and supervision.

Also, Hong Kong companies, with their wealth of international experiences and strengths in grasping and analysing information from overseas, can effectively conduct project risk assessment and provide the necessary risk management services for project investment.

Co-operation in investment and trade is another priority in building the Belt and Road. China hopes to collaborate with countries along the route to study ways to advance investment and trade facilitation and remove investment and trade barriers in order to expand the horizon for multilateral investment.

At the same time, efforts should be made to optimise the division of labour and distribution of the industry chain, as well as synergise the upstream and downstream industry chain with related industries with a view to enhancing the region’s industrial support and comprehensive competitiveness. This will include encouraging joint efforts in establishing different types of industrial parks in the hope of collaborating with Belt and Road countries in promoting the development of industry clusters.

The PRD is the first region in China to open up to the outside world. Today, PRD enterprises are highly internationalised and are leading the country in both the ‘bringing in’ and ‘going out’ strategies. As at the end of 2015, Guangdong ranked top in the country in terms of the number of foreign-invested enterprises and amount of outbound direct investment.

Guangdong enterprises have a competitive edge in technology, capital and management. As their ability in participating in international competition continues to increase, they possess the right conditions to ‘go out’.

At present, as China’s economy is undergoing transformation and upgrading, constraints in the domestic resource environment are tightening, labour cost is rising and corporate profit margin is dwindling. If these industry players can leverage on the advantages of Guangdong’s manufacturing industry and capture opportunities generated by the Belt and Road strategy, they should be able to quicken their pace of ‘going out’ and expanding their international business.

HKTDC Research conducted a questionnaire survey of over 200 Guangdong enterprises in the second and third quarters of 2016. According to the survey, 80% of the enterprises indicated that they would consider exploring business opportunities in countries along the Belt and Road in the next 1-3 years.

Among enterprises that would consider exploring Belt and Road opportunities, the majority of them said they hoped to increase product sales to Belt and Road markets. Some of them opted to invest in setting up production factories in the Belt and Road or source various kinds of consumer goods/food products/raw materials there for supplying to the mainland market, while others hoped to build transit warehouses in Belt and Road countries in order to enhance their international logistics efficiency.

With regard to locations along the Belt and Road where the surveyed enterprises showed interest in exploring business opportunities, the vast majority of them (83%) chose Southeast Asia, including ASEAN countries. The Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area is not only an important transport and logistics hub for the Maritime Silk Road, but has also established effective supply chain relationships with Southeast Asian countries.

For many years, Hong Kong service providers have been assisting enterprises in Guangdong and other mainland regions in managing their trading and investment activities in Hong Kong and in foreign markets. As China advances the Belt and Road development strategy and further encourages enterprises to ‘go out’ to invest offshore, Hong Kong service providers should further strengthen co-operation with Guangdong in such areas as finance, law, logistics, taxation, marketing and risk assessment in a move to capture Belt and Road opportunities.

When mainland enterprises go abroad to establish sales networks, make direct investment, and carry out sourcing and various kinds of acquisition, they need to raise funds in US dollar or other foreign currencies to finance their activities. Currently, enterprises raising funds for their offshore investment projects through the banking system or other financing channels in the mainland are still subject to a lot of restrictions.

If action is to be taken to make it easier for mainland enterprises to make use of the Hong Kong platform to raise funds for their offshore business by taking advantage of its free flow of capital and wide range of professional services, it can effectively resolve their investment and financing problem in the course of ‘going out’. Apart from bank financing, Hong Kong’s financial services and investors, such as venture capital and private funds, not only can provide equity fund but also inject international elements into mainland enterprises. For instance, they can set up an international company through Hong Kong to carry out cost-effective equity and debt financing for individual ‘going out’ investment projects and support the operation and development of the projects.

Moreover, as Hong Kong and Macau forge closer ties with the ports and airports in the Bay Area and in other parts of the PRD, such efforts can be further extended to co-operation with ports in foreign countries. Specifically, they can form alliances with ports in Southeast Asian countries along the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road with the aim of promoting goods import and export facilitation, such as customs clearance, integration of ports and free trade zones etc. These developments are bound to raise the competitiveness of the Bay Area in terms of production, sales, supply chain management, international logistics warehousing and distribution.

Cross-border online sales is an example. The developed transportation and logistics networks in the Bay Area have provided great convenience to consumers in shopping online and to small commodity producers in developing e-commerce. Currently, online shopping and e-commerce in the mainland mainly focus on the domestic market, and international business has yet to be developed.

Hong Kong is one of the most popular cross-border online shopping grounds. It has a sound e-commerce platform and offers network security and protection of personal data privacy. Hence, it has won the trust of foreign users who attach importance to network safety.

Hong Kong also has in place different international payment instruments and third-party payment platforms which can facilitate consumers’ cross-border online shopping activities. Moreover, Hong Kong has a highly efficient global logistics network, with service suppliers providing consumers with effective consolidation, purchase, international transhipment and customs clearance services. As such, it can serve as an ideal platform for foreign consumers shopping online for products in the Bay Area and other mainland regions, and for netizens in the Bay Area searching for trendy foreign goods.

If Guangdong and Hong Kong can jointly strengthen goods flow and further implement facilitation measures for the customs clearance and inspection of import and export goods, it can certainly promote the development of online business in the Bay Area.

Conclusions

Outstanding regional economies such as the San Francisco Bay Area, New York Bay Area and Tokyo Bay share a common feature, that is, their entire area is made up of a number of clusters with strong interaction with one another. Enterprises in the clusters develop on a mutually beneficial basis while sharing competitive advantages of the cluster.

The fact that enterprises in the clusters are distributed in different cities in the bay area has raised the degree of urban integration of the entire area. As such, the economic operation of the bay area advances as a whole. For instance, some development strategies must be formulated from the angle of the whole area in order to protect the economic benefits of the bay area. In light of this, the National Development and Reform Commission mapped out the plan of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area as a collective economy.

However, unlike foreign bay areas in San Francisco, New York and Tokyo, or bay areas in the mainland, such as Bohai Rim and Yangtze River Delta (YRD), the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area embodies three places with different political, administrative and economic systems. Hence, it is not surprising that many hurdles exist in the planning of the Bay Area as a whole. The authority should not over-rely on the analysis of a single expert when mapping out such plans and must hold consultation and discussion with all stakeholders concerned.

According to analysis, the ‘single core’ feature is shared by many leading bay areas in the world. For instance, the New York Bay Area has New York City as its core, Tokyo Bay is centred round Tokyo City, while the San Francisco Bay Area has San Francisco as the core and San Jose as a secondary centre.

In the case of the PRD Bay Area, Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Hong Kong are the three major cities with similar population size and economic strength. How to integrate these cities to develop jointly in the Bay Area and collaborate in carrying out overseas promotion is an issue that warrants attention.

In the Guiding Opinions of the State Council on Deepening Pan-Pearl River Delta Regional Co-operation, it was proposed that the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area is to be positioned as the engine driving the growth of the Pan-PRD region as well as Southeast Asia and South Asia. In strengthening ties with inland regions, such as central-south and southwestern China, connecting with the world and covering Southeast Asia and South Asia, Hong Kong and the PRD can complement each other by way of division of labour and synergy.

In sum, Hong Kong, as an international business platform and financial centre, should continue to maintain foreign ties while taking advantage of the Bay Area’s connection with the hinterland to enhance the strength of the Bay Area in propelling the development of an even wider area. Where specific division of labour is concerned, past experience has shown that not only first-tier cities like Hong Kong, Guangzhou and Shenzhen wish to become regional or international financial, trade and shipping centres capable of attracting the presence of international corporations and business activities, even second- and third-tier cities also hope to join the fray and develop high value-added industries.

With reference to the directions for development of economic industries and urban integration of the San Francisco and other bay areas, the planning of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area as a collective economy should follow the macro directions of future developments. It was mentioned in the Guiding Opinions that Pan-PRD has to clean up the various rules and practices impeding the reasonable flow of production factors. By so doing, all kinds of production factors can flow freely and orderly across different regions.

Moreover, in order to create an environment conducive to the transformation and upgrading of existing industry clusters and the healthy growth of new industry clusters, Guangdong and Hong Kong should strengthen co-operation in areas such as increasing market attraction, optimising business environment, and nurturing and attracting talent. This will improve the ability to compete with other regions in the mainland and overseas under the megatrend of globalisation, and in turn attract more domestic and foreign investors and commercial activities to establish a presence in the Bay Area.

In terms of population, size and total economy, the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area is more or less on a par with most of the advanced bay areas in foreign countries. If the Bay Area can operate as an integrated market where market access and circulation are concerned, it is bound to attract investment, bolster the development of high-tech and innovation industries, and elevate the Bay Area to the level of world-class city cluster.

All in all, Hong Kong can enhance its functions in financing, international operation and risk management. It should also aim to strengthen co-operation with PRD enterprises, enhance its role as an international business platform, drive industries in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area to undergo transformation and upgrading, and give full play to the core values of its role as a ‘super connector’ in the building of the Belt and Road.

[1] The Bay Area: A Regional Economic Assessment, Bay Area Council Economic Institute, October 2012