The inclusion of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area in China’s national strategies, such as its 13th Five-Year Plan and Vision and Actions on Jointly Building the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, will bring about new opportunities for the development of Hong Kong in the years to come. In this connection, action should be taken as soon as possible to map out plans taking advantage of Hong Kong’s strengths in financial services, professional services and international ties in order to enhance co-operation with Guangdong as well as to explore new horizons and add new vitality to the sustainable growth and prosperity of Hong Kong.

Hong Kong’s strengths in financial services, professional services and international ties can also contribute to the transformation and upgrading of industries in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area, building the Bay Area into a world-class city cluster with international competitiveness as well as a leading economic growth engine for the mainland, driving the development advantages of the Pan-Pearl River Delta (PRD) region encompassing central-south and southwestern China. The Bay Area will also play an important role in building the Belt and Road. With reference to other economically advanced bay areas in the world and analysing the development of Hong Kong and the PRD, the following initial thoughts regarding the future industrial and trade development of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area and the roles played by Hong Kong may serve as the reference for further discussion.

Development Advantages of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area

1. Transportation and Logistics

As a collective economy, the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area is home to a number of leading airports and ports in the PRD region, with air and sea cargo throughput ranking first not only in China but also in the world. The PRD, covered by an extensive network of railways and highways with the Bay Area as the core, offers multimodal transport both internally and externally conducive to logistics development.

Compared with other regions in the Chinese mainland and overseas, the Bay Area, as a major passageway for air, land and sea transport linking countries along the Belt and Road, has obvious advantages in terms of geographical location and logistics infrastructure.

2. Upstream and Downstream Industry Supply Chain

Among all provinces and cities in China, Guangdong ranks first in terms of industrial value-added and export, while the PRD accounts for 80% of the industrial value-added and 95% of export for the province. Despite rising production costs in the PRD in recent years, thanks to its strengths in logistics, industrial structure and comprehensive supporting facilities, the majority of enterprises in the region still opt to retain their production lines there while taking action to move towards automation and high value-added production. According to findings of a questionnaire survey conducted by HKTDC Research, 70% of the surveyed manufacturers and traders still see the PRD as the most important production or sourcing base, with 81% sourcing raw materials and semi-manufactures in the PRD for production activities. Among companies which have plans to expand or relocate their factories, 59% said they would still choose the PRD, while the rest mostly opt for other mainland regions close to the PRD or Southeast Asia. In fact, some enterprises which have already relocated to northern Vietnam pointed out that one of the advantages of investing there is its proximity to the supply chain in the PRD which helps to raise production efficiency and lower logistics cost.

3. ICT and High-tech Industry Cluster

Under China’s innovation-driven development strategy, a high-tech industrial belt has gradually taken shape in the PRD. The PRD High-tech Industrial Belt is one of the three national-level belts of its kind approved by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST). This belt covers six national high-tech industrial development zones in Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Foshan, Zhongshan, Zhuhai and Huizhou; three provincial high-tech industrial development zones in Dongguan, Zhaoqing and Jiangmen; two national software industrial bases in Guangzhou and Zhuhai; three national high-tech products export bases; 12 national '863' achievement transformation bases; and one national-level university technology park.

In 2015, the shares of advanced manufacturing industry and high-tech manufacturing industry amounted to 53.9% and 31.8% in PRD’s total value-added industrial output respectively; R&D spending as a share of GDP reached 2.7%; the number of applications for invention patents per 1 million people was 1,728; ownership of invention patents per 10,000 people was 23.33; and technology self-sufficiency rate was over 71%.

4. International Financial and Professional Services

Compared with other city clusters in the mainland, the PRD Bay Area has the unique advantage of encompassing Hong Kong, an international financial centre, in its ‘one-hour economic circle’. Hong Kong, with its large pool of professional service providers and international talent, as well as economic and judicial systems different to those of the mainland, is an ideal gateway for multinational companies entering the Asia and China market.

According to a survey conducted by the Hong Kong SAR government, as of June 2016 there were a total of 3,731 regional headquarters and regional offices in Hong Kong which represent their parent companies outside Hong Kong in handling their business in the Chinese mainland, Northeast Asia and Southeast Asia. As such, Hong Kong has been a leading region in the world for many years in attracting foreign direct investment and exporting outbound direct investment. Moreover, Hong Kong accounted for 52% of China’s cumulative utilised foreign investment as at the end of 2016 and about 60% of its cumulative foreign direct investment as at the end of 2015.

Development Prospects for Economic Integration of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area

Although the political and legal systems of Guangdong, Hong Kong, and Macau differ greatly, through existing co-operation frameworks between governments of the three places and co-operation platforms such as CEPA and free trade zones, trade between Guangdong and Hong Kong and between Guangdong and Macau is basically liberalised. Hong Kong and Macau already have plans to conduct negotiations on free trade agreement, which, when completed, will turn Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macau into one free trade zone.

In view of the fact that Hong Kong is a service platform for the mainland in its ‘bringing in’ and ‘going out’ strategies, players in the industry clusters in Guangdong and Hong Kong, including production enterprises, service suppliers, capital providers, universities and R&D centres, have already established close ties with one another and the two places have practically formed a collective economy. Connections between Guangdong and Hong Kong in terms of people flow, logistics, transportation, capital flow, commercial existence and corporate investment can well testify to this.

It can be expected that upon completion of the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge and Shenzhen-Zhongshan Bridge, transport links, customs clearance and trade activities at the Pearl River Estuary will be further enhanced. One of the objectives of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area plan is to further deepen co-operation in the Bay Area and co-ordinate the connectivity and construction of infrastructural projects, including ports, airports, railways and highways in Hong Kong, Macau and PRD cities.

Efforts should be made to expand the liberalisation of and co-operation in financial and services sectors; promote the free flow of factors of production, products, technology and services within the Bay Area; create an environment conducive to the transformation and upgrading of existing industry clusters and the growth of new industry clusters. Action should also be taken to attract more domestic and foreign investors, as well as trading and commercial activities to the Bay Area in a bid to create more room for development and business opportunities for cities in the area.

In the US, the San Francisco Bay Area (SFBA) comprises nine counties. While each county has its own characteristics and advantages, the rate of economic and industrial development and urbanisation of the entire SFBA is very high and interaction among the nine counties is extremely strong. Industry clusters in the sub-regions of the SFBA are similar, which mainly include industries taking advantage of local talent, such as professional services, scientific research and technical services, as well as tourism-related industries.

The majority of the industries with outstanding performance in the SFBA also have a presence in almost all the sub-regions. While the three largest and most important industry clusters in the SFBA established their foothold in the San Francisco and San Jose sub-regions, three-quarters of the sub-regions house at least two industry clusters which are developing well in the SFBA. Also, residents in the SFBA commute between different sub-regions every day and ties between all the sub-regions are close. This shows that the economic operation of the SFBA works as a collective whole.

The high degree of interaction between the sub-regions means that any development strategy which takes into consideration just one county or sub-region will miss out on benefits which can only be brought about by taking the entire bay area into account [1].

In a move to meet demands of the market and of their own development, PRD enterprises have started to establish their presence in more than one city. For instance, TCL Communication Technology Holdings Ltd has its production base in Huizhou and China headquarters in Shenzhen, while its Hong Kong office takes charge of overseas business. Another example is Welon (China) Ltd, which set up its base in Huizhou at first, but as business continued to expand the company began to build production lines for different sporting goods in various PRD cities and even set up its China headquarters and production R&D centre in Guangzhou. In order to better co-ordinate its expanding overseas business, Welon may consider setting up an office in Hong Kong.

It can be expected that PRD enterprises will increasingly carry out their business development according to the competitive advantages and economic environment of different cities in the Bay Area. This will in turn bolster the economic and industrial development as well as urbanisation rate of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area, while interaction between cities within the Bay Area will also grow stronger.

Hong Kong’s Role in the Future Development of the Bay Area

1. Global Supply Chain Management and Logistics Centre

In recent years, as production cost in China continues to climb, many enterprises have relocated or extended their production lines to emerging countries such as Vietnam and Bangladesh. As a result, a supply chain linking China, East Asia, Southeast Asia and South Asia has gradually been formed to become one of the world’s three largest regional supply chains on a par with the Americas and Europe.

Under the pressure of rising wages and labour shortage, many labour-intensive enterprises in the PRD, such as those engaged in garment and footwear manufacturing, have relocated their production lines to popular spots in Southeast Asia and South Asia. This has caused China’s share in the garment imports into the US and EU to drop from 39% and 42% respectively in 2012 to 36% and 34% respectively in 2016. During the same period, China’s share in the footwear imports into the US and EU also fell from 72% and 51% respectively in 2012 to 58% and 45%.

However, it is interesting to note that the share of Chinese goods in total imports into the US and EU actually rose rather than dropped, while China’s share in global industrial products exports jumped from 16.8% in 2012 to 18.6% in 2015. This shows that China’s manufacturing industry and exports are gradually moving towards high value-added and upstream products.

According to data released by the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the share of China’s semi-manufactures exports in the world rose from 9.6% in 2010 to 12% in 2014. A large part of this was exported to Southeast Asia and South Asia, which reflects the increasingly close supply chain relationships between countries in these regions and China. Currently, the PRD is the ‘world factory’ for a wide range of consumer goods and intermediate products. As Chinese enterprises and other multinational corporations expand their processing and production activities in Southeast Asia and South Asia, they have to import various parts, components, accessories and industrial materials produced in other countries, as well as those produced by their factories in the PRD and their upstream suppliers.

Since the industrial base of emerging markets in Southeast Asia and South Asia is still in its nascent stage, if local and foreign invested enterprises wish to expand their production in these countries, they must import more advanced processes. And in so doing, they have to seek the support of foreign professionals and services, including a wide range of engineering, equipment manufacturing and environmental services.

Hong Kong is an international commercial and logistics centre in Asia, its service suppliers possess rich professional knowledge and have established extensive business networks in many countries and regions, hence, it can help China connect with other regions by providing one-stop services in supply chain management, including the above mentioned production, logistics and environmental services.

In addition to building a supply chain for processing and production activities, the rapid development of logistics supply chain services is not to be overlooked as the booming Chinese economy and other emerging Asian countries has pushed up the income level of the population, which in turn has generated great demand for imported consumer products.

In particular, as e-commerce has grown in leaps and bounds in recent years, the way of doing business has undergone immense changes. And as consumer products are moving faster and faster, the demand for high-efficiency international supply chain services is also bound to expand further. Judging from the structure and growth of Hong Kong’s re-export trade currently, the role played by its logistics sector is becoming increasingly important in Asia’s regional supply chain.

Capitalising on the service networks and efficiency of the airports and ports of Hong Kong, Shenzhen and Guangzhou, as well as the close co-operation between the Guangdong and Hong Kong customs and port authorities (such as the new logistics services offered by the one-stop air-land multimodal super trunk line in Hong Kong Airport and Nansha Bonded Port Area Logistics Park), the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area can be expected to maintain its position and competitiveness as a logistics hub in the course of its development as a supply chain linking major regions around the world and as a regional supply chain serving China in its move to connect with Asia.

Within the Bay Area there are five airports, namely in Hong Kong, Macau, Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Zhuhai, while Hong Kong, Guangzhou and Shenzhen also have their own international ports. How to co-ordinate these facilities and pursue rational development, complementariness and co-operation in order to strengthen the competitiveness of the Bay Area will have to depend on the communication and collaboration between the participating members.

In the case of Japan’s Tokyo Bay, there are six ports, namely in Tokyo, Yokohama, Yokosuka, Kawasaki, Chiba and Kisarazu. In order to avoid vicious competition, these ports were carefully planned with the aim of promoting co-ordinated division of labour and co-operation. Each port performs different functions according to its strengths and characteristics and all six synergise to form a port cluster.

The planning and development of infrastructural facilities such as ports and airports in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area can refer to the Tokyo Bay model in achieving co-ordinated division of labour and complementariness. For instance, Hong Kong, as an international aviation hub, has a strong network of international air routes (for both passenger and cargo flights).

Through strengthening water and land transport links with Shenzhen’s airport and ports as well as customs co-operation, Hong Kong can provide multimodal transport services linking mainland cities with foreign markets. Also, upon completion of the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge, Zhuhai Airport can forge closer co-operation ties with Hong Kong Airport and further strengthen the competitiveness of the Bay Area as an international logistics hub.

Where promoting logistics resources integration and complementariness in the Bay Area is concerned, Guangdong and Hong Kong can further enhance collaboration in a move to raise the level of advanced and highly efficient services such as online logistics, customs clearance, payment, source tracing and tracking in international trade.

2. Advanced Production and Innovation R&D Centre

Technology and innovation are the main direction for future development. In the course of building the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area into a city cluster with global influence and competitiveness, technology and innovation are important drivers. Technological development not only aims to enhance the R&D capability of the Bay Area, but also extensively apply technology in different areas, such as smart production, smart cities, Internet of Things, environmental protection and energy saving, in order to raise the level of overall economic efficiency and sustainable development. Industrial development in the PRD region can also attract more input into R&D and propel a benign cycle.

Information on Guangdong’s planning shows that the PRD will, leveraging on its industrial advantages, build five high-tech industry clusters:

(a) Using Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Foshan as the fulcrum to drive development of the information industry in cities including Zhuhai and Zhaoqing, and to expedite the pace of building a national-level information industry base in the PRD.

(b) Using Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Dongguan and Huizhou as the fulcrum to create a number of new energy industry clusters and establish a new energy car production base; using Shenzhen, Dongguan, Foshan and Zhongshan as the fulcrum to build a national solar photovoltaic high-tech industrial base to support the development of low-carbon economy in Shenzhen, Jiangmen and Zhaoqing, and to accelerate the pace of Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Foshan and Dongguan in creating a national-level new energy, environmental protection and energy saving industrial base.

(c) Using the Torch Plan new materials and niche industry base and the national high-tech industrial base for new materials in Guangzhou and Foshan as the pillar to create a leading national-level new materials industry base.

(d) Using the two national biological industry bases in Guangzhou and Shenzhen as well as Zhongshan as the support to create a national bio-medicine and leading modern innovation industry base.

(e) Using Guangzhou and Shenzhen as the core to develop a world-class LED new light source industry integrating Shenzhen, Dongguan, Huizhou, Guangzhou, Foshan, Zhongshan and Jiangmen, and to form an LED new light source upstream-downstream integration industrial belt in the PRD.

Unlike the San Francisco Bay Area in the US whose industrial structure focuses on professional/scientific and technical services as well as the information industry, the industrial structure of the PRD covers a wide spectrum of industries ranging from high-tech to a diversity of traditional manufacturing.

While technology can be applied in different sectors and smart cities, internet of things, environmental protection and energy saving are major directions. How to promote the integration of advanced technology, modern professional services and traditional industries in order to accelerate industrial transformation and upgrading in the Bay Area is a development direction that warrants attention. For instance, manufacturing industry production lines in the PRD should move towards automation, while industrial associations in various cities in the Bay Area should strengthen exchanges and co-operation, combine different industrial enhancement resources and technological resources, and develop automation equipment suitable for their respective industries.

Today, mainland enterprises boast sound R&D ability and have developed a wide range of popular technologies and products in such areas as ICT applications and solutions as well as mobile device applications (apps). However, not many enterprises manage to extend such technological applications from local level to national level, neither can they tap the international market by using technologies that meet international standards. Meanwhile, although China is still at a nascent stage in certain advanced technologies, it is finding it difficult to import foreign technologies directly into the mainland for application due to different technical specifications and user experiences.

Compared with the mainland, Hong Kong is weaker in terms of scientific research input and overall R&D capability. However, Hong Kong companies are not only well-versed in international technological trends and technical standards, but also have established extensive international market networks. As such, Hong Kong can collaborate with Shenzhen as well as cities within the Bay Area in forging closer ties in personnel exchange, technological application, and technical specifications in relevant technological sectors.

Such joint efforts not only can help advance commercialisation of mainland technological achievements and develop overseas markets, but also effectively bring in the right foreign technologies for mainland industry players for local application, which will in turn boost the overall development of the Bay Area.

In certain high-tech industries, e.g. internet of things applications and development of next generation internet, some mainland enterprises currently still lack the necessary expertise, which has more or less restricted the relevant R&D and technological application. Hong Kong’s technological industry players have good knowledge about advanced foreign technologies, excel in using technologies developed in accordance with international standards/frameworks, and are experienced in importing foreign technologies. Therefore, they can help mainland projects pursue commercialisation to meet market demand.

Hong Kong, as a regional intellectual property trading hub, offers sound protection to intellectual property and provides excellent professional services. Hence, the SAR has attracted a great number of technology, creative, R&D, design and production companies around the world to use it as a platform for trading intellectual property with the Chinese mainland and other Asian markets.

To meet the demands arising from the development of technology and innovation in the Bay Area, Hong Kong can give full play to its advantages as an intellectual property trading hub to bring in intellectual property, such as technology from abroad, as well as assist the Bay Area in launching its R&D achievements onto the market and tap the international market.

Financial technology is another sector where Hong Kong can participate in the technological and innovation development of the Bay Area. In Guangdong’s 13th Five-Year Plan, it was put forward that efforts would be made to encourage Shenzhen and Hong Kong to jointly build a global financial centre.

Hong Kong is already an international financial centre in its own right. As its ties with the mainland financial sector become increasingly close, it provides a sound co-operation base and excellent opportunities for the development of financial technology. For instance, for financial technology companies wishing to develop financial technology for stock investment, Hong Kong offers room for growth because its stock market has connections with both the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets.

Any enterprise wishing to engage in financial technology must possess knowledge in financial services and the necessary technical background. Hong Kong is not only home to a large pool of professionals rich in financial experiences and knowledge, but also has in place transparent regulations and a sound supervision system which guarantees information safety. As such, it can join hands with the technical personnel of the Bay Area in developing the right financial technology.

If Guangdong and Hong Kong can coordinate the development and application of financial technology in the Bay Area, including system standards and connection, the application and research of financial technology in the Bay Area is bound to reach an advanced level.

It can be expected that more and more entrepreneurs and investors in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area will be encouraged to participate in various technological innovation enterprises. Apart from demand for financial resources, these enterprises are also in dire need of supporting services in technology, market network and corporate development.

Technological innovation enterprises in Shenzhen and in the Bay Area at large can capitalise on Hong Kong’s advantages, such as the free flow of information and capital, extensive international market networks, and sound corporate management, to enhance their development ability. In encouraging Shenzhen and Hong Kong to jointly build an innovation platform, efforts have to be made to strengthen exchanges and connections between the R&D institutions and technological enterprises in the two cities in a bid to create a technological co-operation platform. Steps should also be taken to extend the platform to other related financial and professional services in the hope of combining each other’s advantages.

Pooling talent is an important factor in propelling technology and innovation. In attracting experts, especially experts from overseas, Hong Kong can join hands with Shenzhen and play to their respective strengths.

Foreign experts may find it easier to adapt to living in Hong Kong, an international metropolis, than in mainland cities. So, in order to attract foreign professionals to form R&D teams with mainland and Hong Kong personnel, action can be taken to form teams straddling Hong Kong and neighbouring Shenzhen. In so doing, foreign professionals can live in Hong Kong, where the environment is international, while maintaining close contacts with research team mates in the PRD region, in particular Shenzhen.

Hong Kong, with its foreign ties and international background, can be positioned as a base for foreign technological exchanges and co-operation in the Bay Area. Currently, Hong Kong and Shenzhen are planning to jointly build a Hong Kong/Shenzhen Innovation and Technology Park in the Lok Ma Chau Loop. Upon completion, this park can play a leading and demonstrative role in attracting the entry of mainland and leading foreign enterprises, universities and R&D institutions and help bolster the future development of the Bay Area.

3. Building the Belt and Road

Under the Belt and Road Initiative there are five development priorities: policy coordination, facilities connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration, and people-to-people bonds. Among the five, facilities connectivity takes the lead in driving the development of infrastructural projects.

According to the latest estimate released by the Asia Development Bank, from 2016 to 2030, in developing Asia alone, capital required for investing in infrastructural construction amounts to US$1.7 trillion a year. Currently, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are the major players participating in infrastructural projects along the Belt and Road. However, the diverse range of infrastructural construction projects along the Belt and Road require enormous amounts of investment.

The capital, risks, and management technology involved are far beyond the ability of the government and SOEs. Public-private partnership (PPP), which supplies the above investment essentials and brings in different innovative ideas, is crucial to the successful building of the Belt and Road.

The arrangement of PPP projects can be very complex as they involve investors from different countries and each of the multiple investing parties has its own interests in mind. Hong Kong companies have rich experience in PPP projects and Hong Kong, as an international hub, can play the role of a ‘super-connector’ in effectively matching participants in the projects and providing financing solutions.

Guangdong province has long been a major source of investment in China’s overseas contracted projects. Mainland enterprises, in particular Guangdong enterprises, have an edge in contracted projects, while Hong Kong’s professional and commercial services are highly rated in specific areas. For instance, many architectural, surveying and engineering services companies in Hong Kong have reached the world’s top levels. They can provide Guangdong enterprises participating in Belt and Road infrastructural projects with a wide range of services, such as consultancy, design, planning and supervision.

Also, Hong Kong companies, with their wealth of international experiences and strengths in grasping and analysing information from overseas, can effectively conduct project risk assessment and provide the necessary risk management services for project investment.

Co-operation in investment and trade is another priority in building the Belt and Road. China hopes to collaborate with countries along the route to study ways to advance investment and trade facilitation and remove investment and trade barriers in order to expand the horizon for multilateral investment.

At the same time, efforts should be made to optimise the division of labour and distribution of the industry chain, as well as synergise the upstream and downstream industry chain with related industries with a view to enhancing the region’s industrial support and comprehensive competitiveness. This will include encouraging joint efforts in establishing different types of industrial parks in the hope of collaborating with Belt and Road countries in promoting the development of industry clusters.

The PRD is the first region in China to open up to the outside world. Today, PRD enterprises are highly internationalised and are leading the country in both the ‘bringing in’ and ‘going out’ strategies. As at the end of 2015, Guangdong ranked top in the country in terms of the number of foreign-invested enterprises and amount of outbound direct investment.

Guangdong enterprises have a competitive edge in technology, capital and management. As their ability in participating in international competition continues to increase, they possess the right conditions to ‘go out’.

At present, as China’s economy is undergoing transformation and upgrading, constraints in the domestic resource environment are tightening, labour cost is rising and corporate profit margin is dwindling. If these industry players can leverage on the advantages of Guangdong’s manufacturing industry and capture opportunities generated by the Belt and Road strategy, they should be able to quicken their pace of ‘going out’ and expanding their international business.

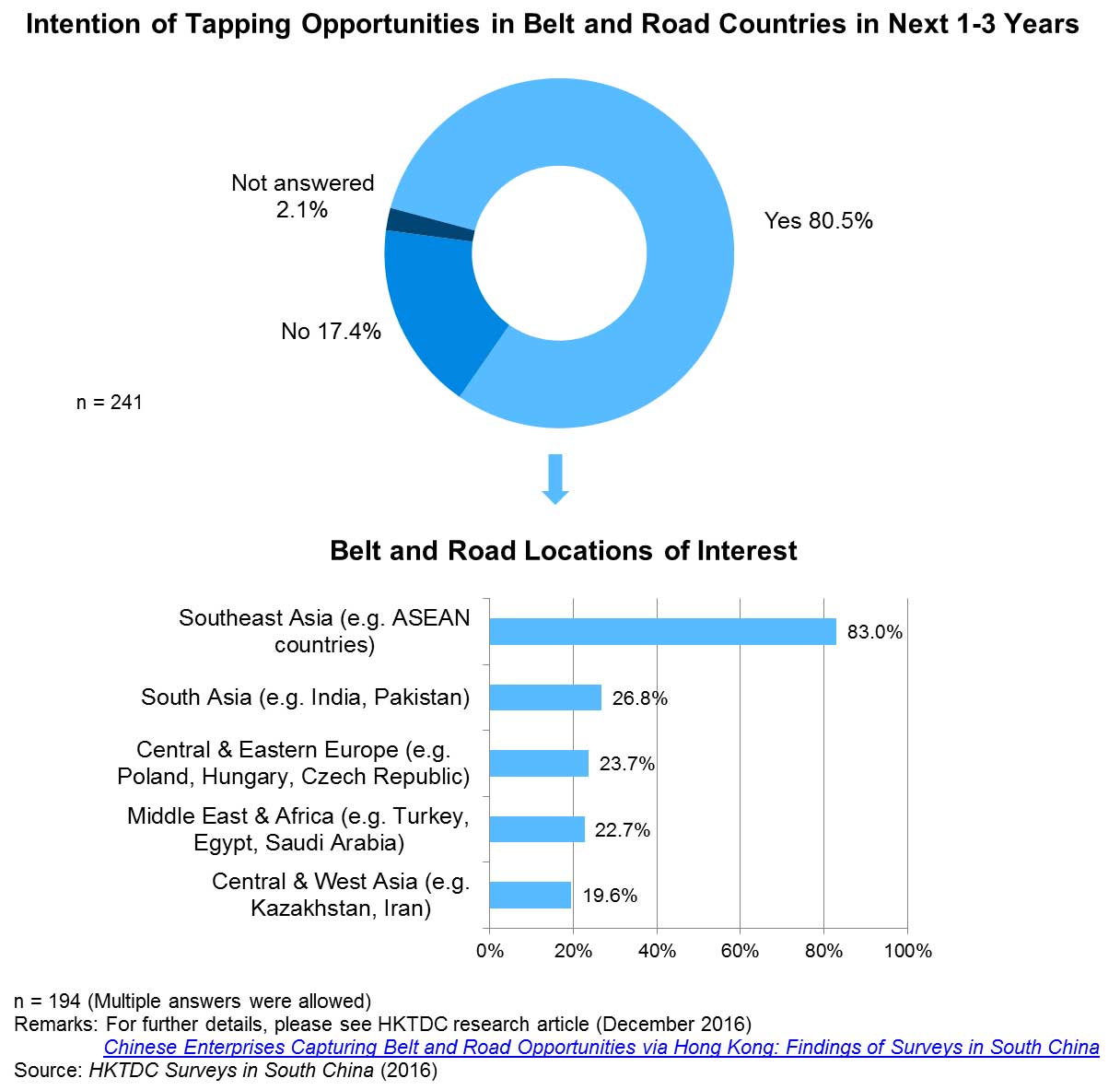

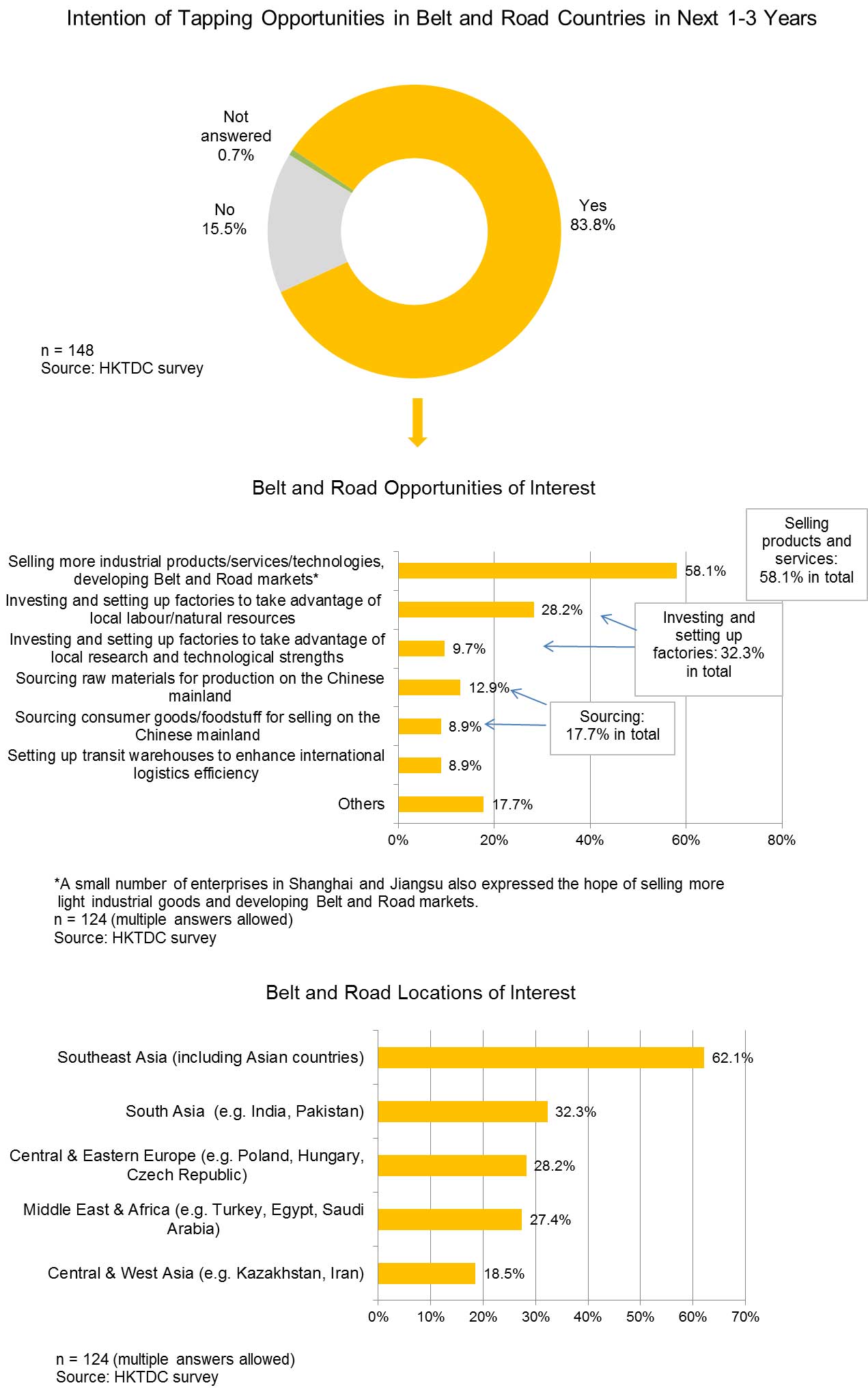

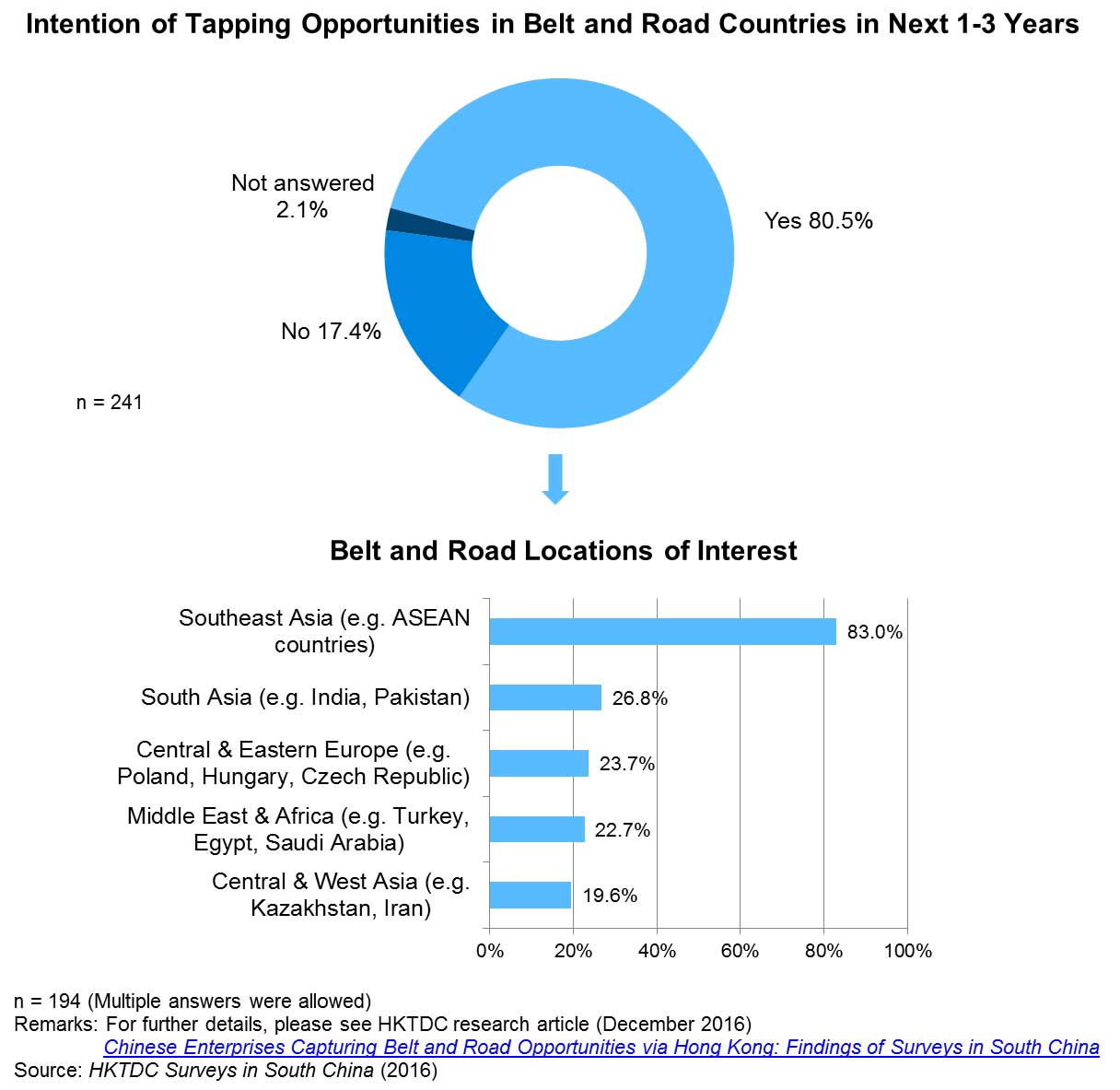

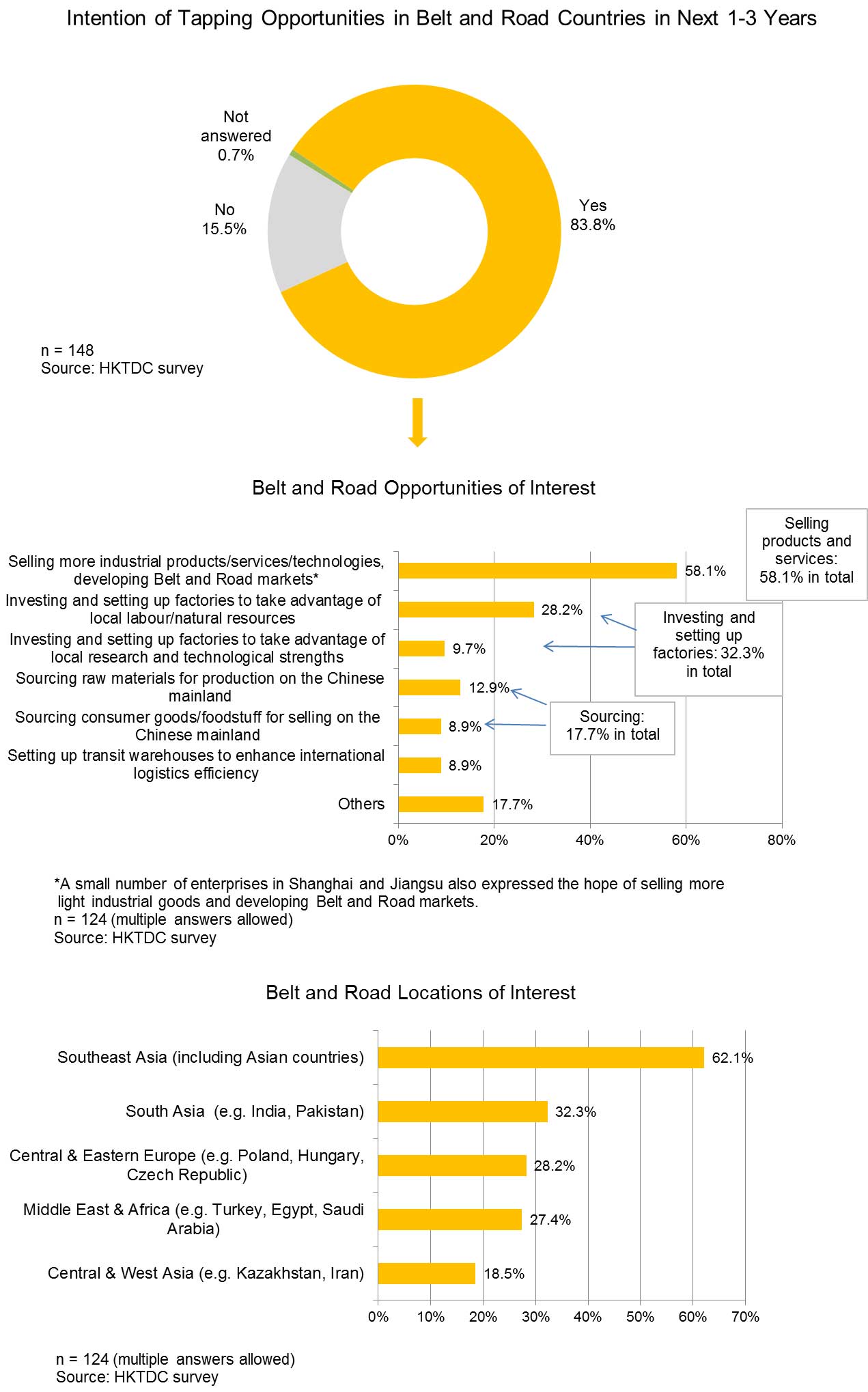

HKTDC Research conducted a questionnaire survey of over 200 Guangdong enterprises in the second and third quarters of 2016. According to the survey, 80% of the enterprises indicated that they would consider exploring business opportunities in countries along the Belt and Road in the next 1-3 years.

Among enterprises that would consider exploring Belt and Road opportunities, the majority of them said they hoped to increase product sales to Belt and Road markets. Some of them opted to invest in setting up production factories in the Belt and Road or source various kinds of consumer goods/food products/raw materials there for supplying to the mainland market, while others hoped to build transit warehouses in Belt and Road countries in order to enhance their international logistics efficiency.

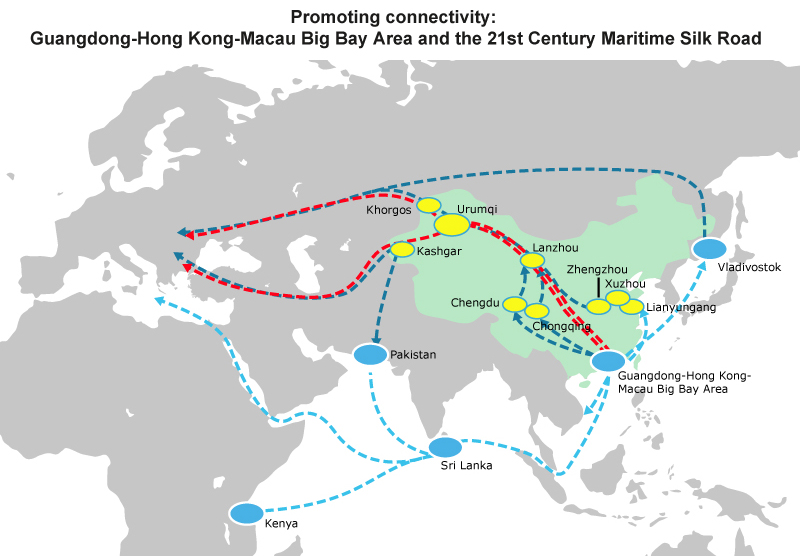

With regard to locations along the Belt and Road where the surveyed enterprises showed interest in exploring business opportunities, the vast majority of them (83%) chose Southeast Asia, including ASEAN countries. The Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area is not only an important transport and logistics hub for the Maritime Silk Road, but has also established effective supply chain relationships with Southeast Asian countries.

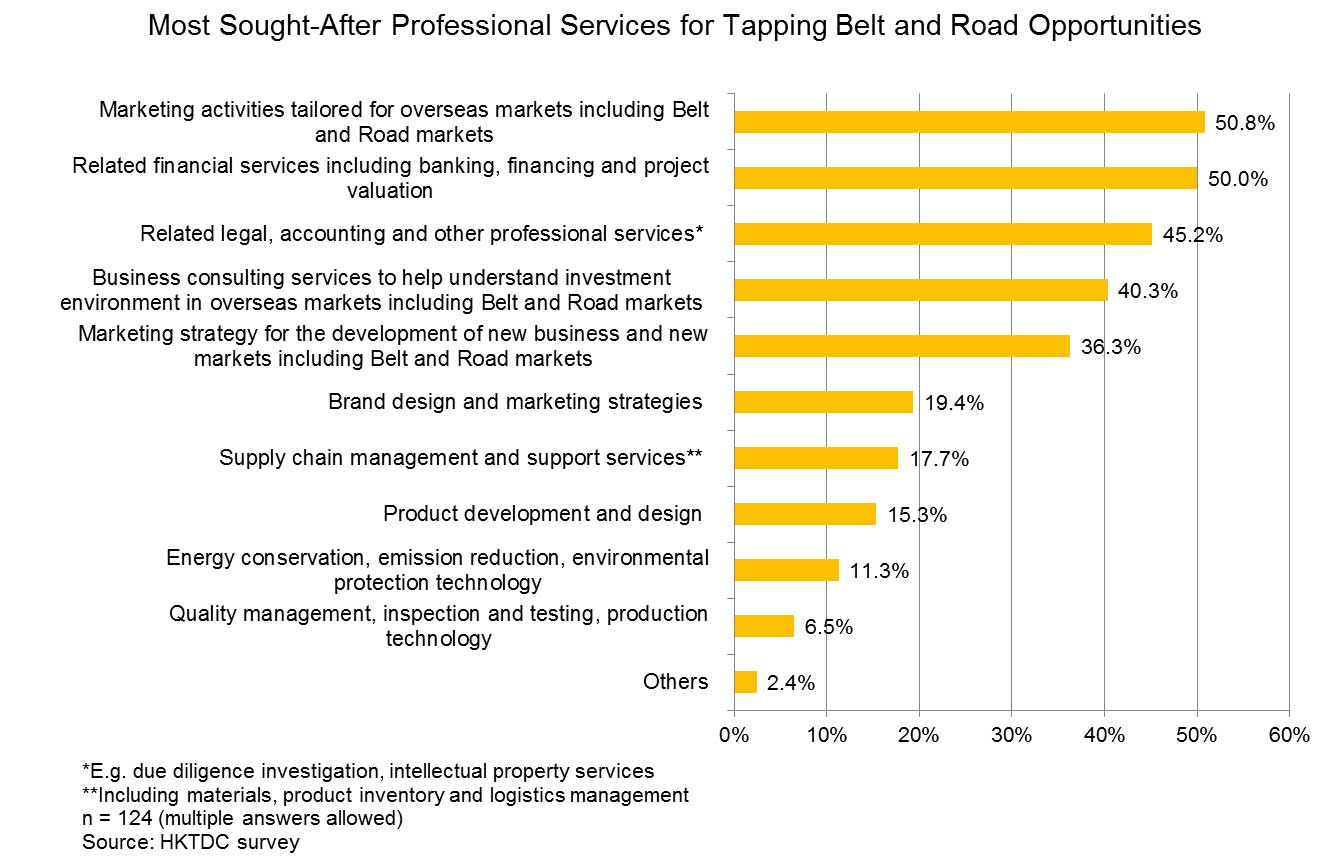

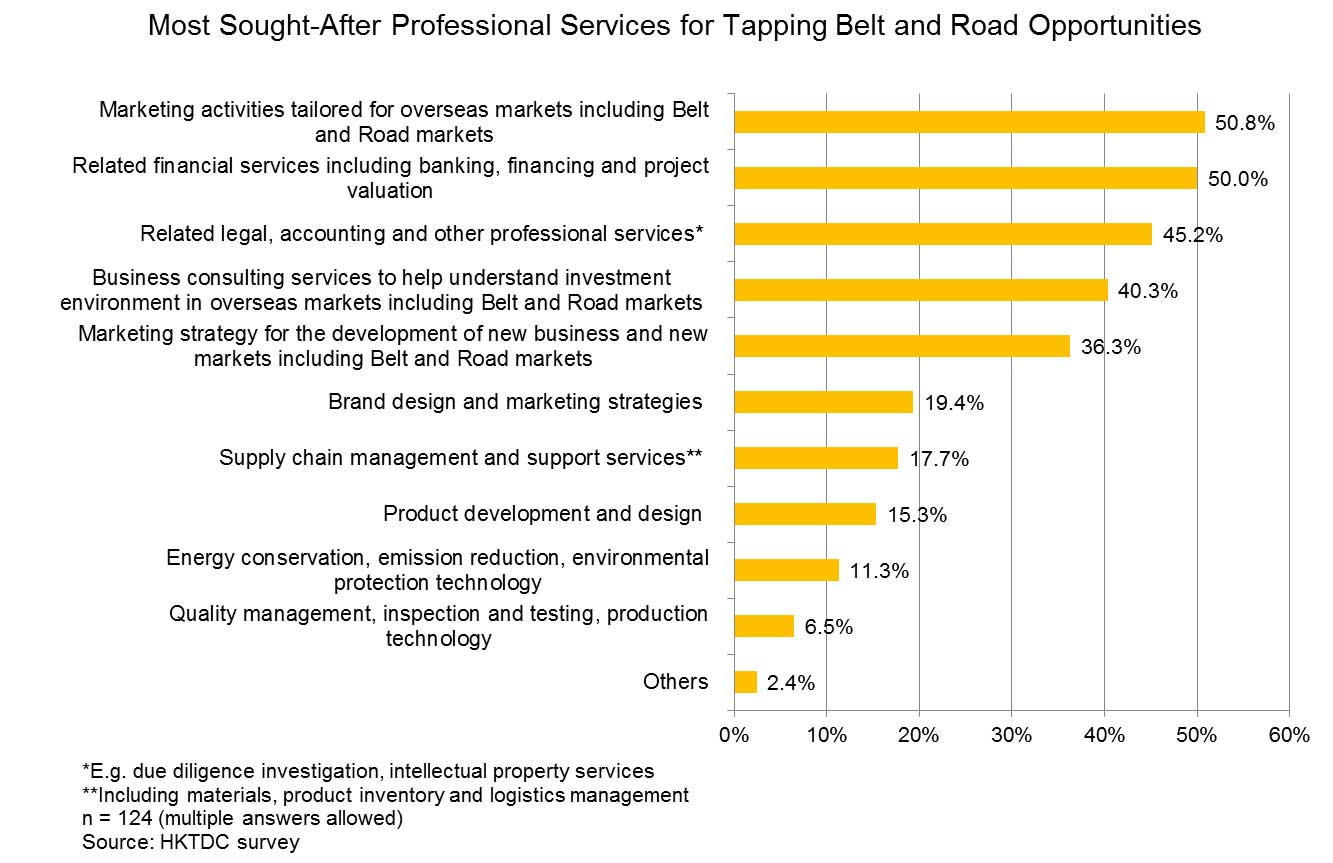

For many years, Hong Kong service providers have been assisting enterprises in Guangdong and other mainland regions in managing their trading and investment activities in Hong Kong and in foreign markets. As China advances the Belt and Road development strategy and further encourages enterprises to ‘go out’ to invest offshore, Hong Kong service providers should further strengthen co-operation with Guangdong in such areas as finance, law, logistics, taxation, marketing and risk assessment in a move to capture Belt and Road opportunities.

When mainland enterprises go abroad to establish sales networks, make direct investment, and carry out sourcing and various kinds of acquisition, they need to raise funds in US dollar or other foreign currencies to finance their activities. Currently, enterprises raising funds for their offshore investment projects through the banking system or other financing channels in the mainland are still subject to a lot of restrictions.

If action is to be taken to make it easier for mainland enterprises to make use of the Hong Kong platform to raise funds for their offshore business by taking advantage of its free flow of capital and wide range of professional services, it can effectively resolve their investment and financing problem in the course of ‘going out’. Apart from bank financing, Hong Kong’s financial services and investors, such as venture capital and private funds, not only can provide equity fund but also inject international elements into mainland enterprises. For instance, they can set up an international company through Hong Kong to carry out cost-effective equity and debt financing for individual ‘going out’ investment projects and support the operation and development of the projects.

Moreover, as Hong Kong and Macau forge closer ties with the ports and airports in the Bay Area and in other parts of the PRD, such efforts can be further extended to co-operation with ports in foreign countries. Specifically, they can form alliances with ports in Southeast Asian countries along the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road with the aim of promoting goods import and export facilitation, such as customs clearance, integration of ports and free trade zones etc. These developments are bound to raise the competitiveness of the Bay Area in terms of production, sales, supply chain management, international logistics warehousing and distribution.

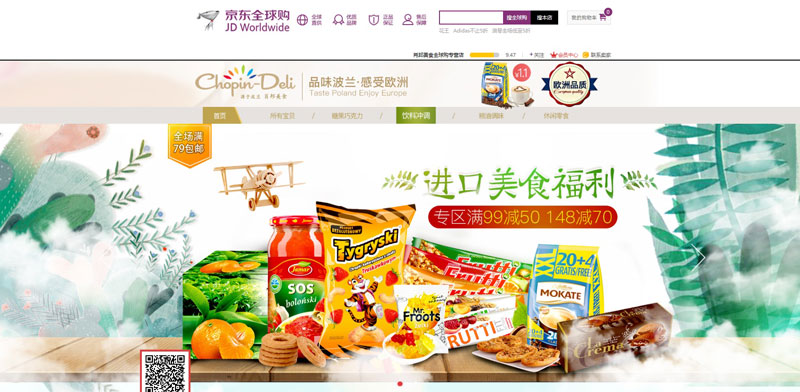

Cross-border online sales is an example. The developed transportation and logistics networks in the Bay Area have provided great convenience to consumers in shopping online and to small commodity producers in developing e-commerce. Currently, online shopping and e-commerce in the mainland mainly focus on the domestic market, and international business has yet to be developed.

Hong Kong is one of the most popular cross-border online shopping grounds. It has a sound e-commerce platform and offers network security and protection of personal data privacy. Hence, it has won the trust of foreign users who attach importance to network safety.

Hong Kong also has in place different international payment instruments and third-party payment platforms which can facilitate consumers’ cross-border online shopping activities. Moreover, Hong Kong has a highly efficient global logistics network, with service suppliers providing consumers with effective consolidation, purchase, international transhipment and customs clearance services. As such, it can serve as an ideal platform for foreign consumers shopping online for products in the Bay Area and other mainland regions, and for netizens in the Bay Area searching for trendy foreign goods.

If Guangdong and Hong Kong can jointly strengthen goods flow and further implement facilitation measures for the customs clearance and inspection of import and export goods, it can certainly promote the development of online business in the Bay Area.

Conclusions

Outstanding regional economies such as the San Francisco Bay Area, New York Bay Area and Tokyo Bay share a common feature, that is, their entire area is made up of a number of clusters with strong interaction with one another. Enterprises in the clusters develop on a mutually beneficial basis while sharing competitive advantages of the cluster.

The fact that enterprises in the clusters are distributed in different cities in the bay area has raised the degree of urban integration of the entire area. As such, the economic operation of the bay area advances as a whole. For instance, some development strategies must be formulated from the angle of the whole area in order to protect the economic benefits of the bay area. In light of this, the National Development and Reform Commission mapped out the plan of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area as a collective economy.

However, unlike foreign bay areas in San Francisco, New York and Tokyo, or bay areas in the mainland, such as Bohai Rim and Yangtze River Delta (YRD), the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area embodies three places with different political, administrative and economic systems. Hence, it is not surprising that many hurdles exist in the planning of the Bay Area as a whole. The authority should not over-rely on the analysis of a single expert when mapping out such plans and must hold consultation and discussion with all stakeholders concerned.

According to analysis, the ‘single core’ feature is shared by many leading bay areas in the world. For instance, the New York Bay Area has New York City as its core, Tokyo Bay is centred round Tokyo City, while the San Francisco Bay Area has San Francisco as the core and San Jose as a secondary centre.

In the case of the PRD Bay Area, Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Hong Kong are the three major cities with similar population size and economic strength. How to integrate these cities to develop jointly in the Bay Area and collaborate in carrying out overseas promotion is an issue that warrants attention.

In the Guiding Opinions of the State Council on Deepening Pan-Pearl River Delta Regional Co-operation, it was proposed that the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area is to be positioned as the engine driving the growth of the Pan-PRD region as well as Southeast Asia and South Asia. In strengthening ties with inland regions, such as central-south and southwestern China, connecting with the world and covering Southeast Asia and South Asia, Hong Kong and the PRD can complement each other by way of division of labour and synergy.

In sum, Hong Kong, as an international business platform and financial centre, should continue to maintain foreign ties while taking advantage of the Bay Area’s connection with the hinterland to enhance the strength of the Bay Area in propelling the development of an even wider area. Where specific division of labour is concerned, past experience has shown that not only first-tier cities like Hong Kong, Guangzhou and Shenzhen wish to become regional or international financial, trade and shipping centres capable of attracting the presence of international corporations and business activities, even second- and third-tier cities also hope to join the fray and develop high value-added industries.

With reference to the directions for development of economic industries and urban integration of the San Francisco and other bay areas, the planning of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area as a collective economy should follow the macro directions of future developments. It was mentioned in the Guiding Opinions that Pan-PRD has to clean up the various rules and practices impeding the reasonable flow of production factors. By so doing, all kinds of production factors can flow freely and orderly across different regions.

Moreover, in order to create an environment conducive to the transformation and upgrading of existing industry clusters and the healthy growth of new industry clusters, Guangdong and Hong Kong should strengthen co-operation in areas such as increasing market attraction, optimising business environment, and nurturing and attracting talent. This will improve the ability to compete with other regions in the mainland and overseas under the megatrend of globalisation, and in turn attract more domestic and foreign investors and commercial activities to establish a presence in the Bay Area.

In terms of population, size and total economy, the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area is more or less on a par with most of the advanced bay areas in foreign countries. If the Bay Area can operate as an integrated market where market access and circulation are concerned, it is bound to attract investment, bolster the development of high-tech and innovation industries, and elevate the Bay Area to the level of world-class city cluster.

All in all, Hong Kong can enhance its functions in financing, international operation and risk management. It should also aim to strengthen co-operation with PRD enterprises, enhance its role as an international business platform, drive industries in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area to undergo transformation and upgrading, and give full play to the core values of its role as a ‘super connector’ in the building of the Belt and Road.

[1] The Bay Area: A Regional Economic Assessment, Bay Area Council Economic Institute, October 2012

Editor's picks

Trending articles

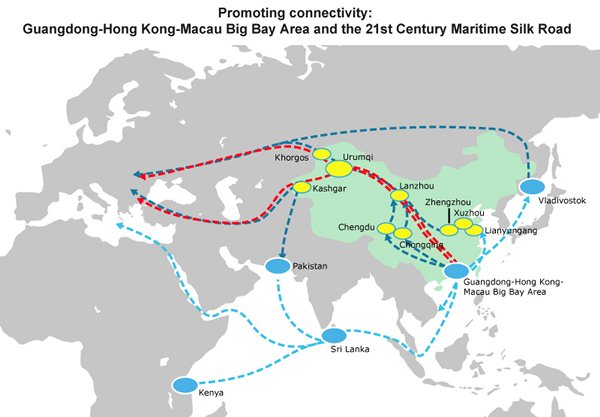

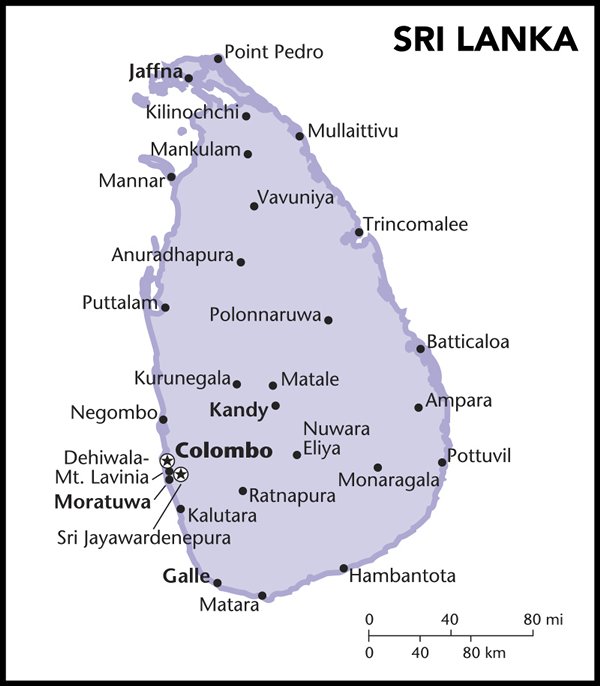

According to Vision and Actions on Jointly Building the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, a key strategy document produced by the Chinese government, the “maritime silk road” will consist of two routes, one of which will run from China's coastal ports to Europe via the South China Sea and Indian Ocean. As the key Eurasian shipping route, the Indian Ocean plays a major role in facilitating China’s overseas trade and the transportation of fuel and raw materials. Sri Lanka, an island country in the Indian Ocean, is seen as one of the vital nodes along the maritime Silk Road. In line with this, the Chinese province of Guangdong will ally with Sri Lanka to build the proposed sea-rail multi-modal transportation corridor as part of its participation in the “One Belt, One Road” initiative and the plan of developing the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Big Bay Area into an international logistics hub as part of the Silk Road Economic Belt.

Sri Lanka’s Logistics Strengths

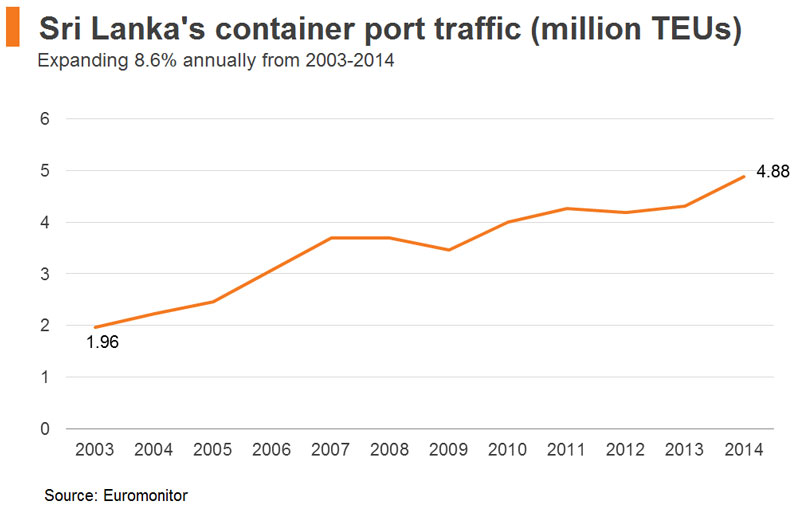

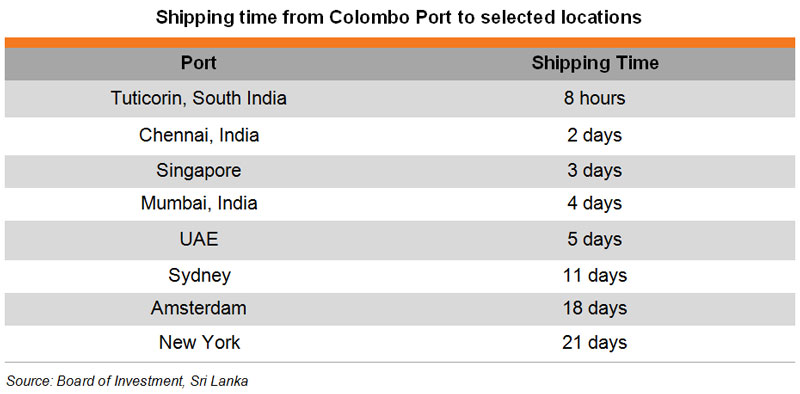

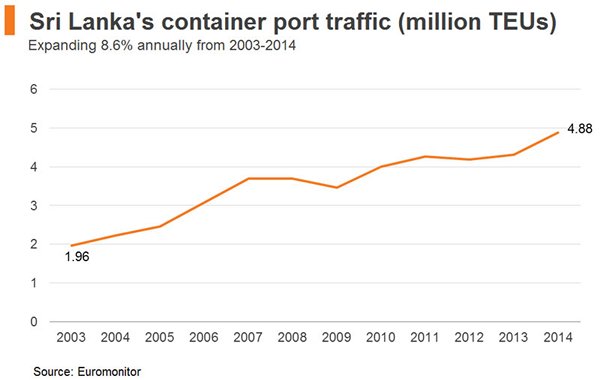

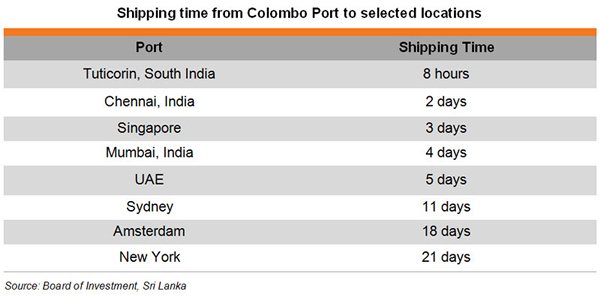

Situated in the Indian Ocean, along some of the world’s busiest shipping routes and close to India, Sri Lanka has a distinct locational advantage, which should see it develop into a key shipping centre and logistics hub in South Asia (See Sri Lanka: An Emerging Logistics Hub in South Asia). Despite being a small economy, with a total trade amounting to about US$31 billion in 2014 (only 4% of India’s US$778 billion), Sri Lanka is an important transhipment hub in the region. It is a site where many shipping companies consolidate and deconsolidate cargo for transhipping to other destinations. In 2014, the Port of Colombo reported a growth of 12.3% in container traffic to 4.88 million TEUs, of which transhipment cargo accounted for 75% of total container throughput.

World Shipping Council statistics show that the Port of Colombo – Sri Lanka’s major container port on the west coast – was the busiest port in South Asia in 2013, handling 4.31 million TEUs. This puts it ahead of India’s largest container port, Jawaharlal Nehru (4.12 million TEUs in 2013).

Port of Colombo

Amid the growing demand for international logistics services, Sri Lanka has launched the Colombo Port Expansion Project (CPEP). Prior to the project, there were three terminals in the Port of Colombo: Jaya Container Terminal, Unity Container Terminal and South Asia Gateway Terminal, with seven main container berths and four feeder berths.

Following the completion of the CPEP, three more terminals will be available. The first of these, the South Container Terminal (developed by Colombo International Container Terminals Limited, a joint venture (JV) between China Merchants Holdings (International) Co Ltd and SLPA) has already commenced operations. This is the first terminal in South Asia that can accommodate a mega-sized vessel. The SLPA-owned East Container Terminal (ECT) will come into operation in late 2015, while the West Container Terminal is still at the planning stage. It is expected that the container handling capacity of Port of Colombo could be increased from slightly more than 4 million TEUs to 12 million TEUs per year, making it one of the world’s largest container ports.

Hambantota Port

In order to further expand the country’s logistics sector, the Sri Lankan government is developing a new port and economic zone in Hambantota, a southern coastal district. Significantly, the designated contractor for the whole project is a JV between China Harbour Engineering Co and Sinohydro Corporation Ltd.

Phase one of the projects has already been completed, delivering a port capable of berthing four vessels and a bunkering terminal that started operation in 2014. The current plan will see the second phase of the port’s development add a container terminal with seven berths, while a dockyard will be added in third phase. It is expected that the construction of phase two will be completed by the end of 2015. While a vast proportion of the project is still under construction, the Hambantota port has already made good progress, handling a total of 388 ships in 2014 - more than double its 2013 throughput.

Although Sri Lanka does not manufacture automobiles, Hambantota is now becoming a transshipment hub for finished vehicles. Given its desirable location, augmented by its deep-water port, carmakers from Japan, Korea and India are increasingly using Hambantota as a nexus for transshipping vehicles built in India, Thailand, Japan and China to markets in Africa, the Middle East, Europe and the Americas. According to SLPA, the port handled 254 Ro-Ro vessels (i.e. ships carrying vehicles) in 2014, an 85% increase on the previous year. The total number of motor vehicles handled approached 190,000 in 2014, compared to about 65,000 in 2013. Aside from vehicles, the Hambantota port is also set to become a transshipment hub for a range of other merchandise, similar to the Port of Colombo. In particular, it is looking to service goods manufactured in OEM plants in other Asian production bases.

Foreign Participation

Despite heavy public and private investment in infrastructure – long considered an essential ”tangible factor” for a logistics hub - Sri Lanka is encountering challenges in terms of “intangible factors”, including access to a sufficient number of qualified professionals and international participants in the field. Not surprisingly, the country’s logistics and transport industry still lags behind a number of the region’s other leading hubs, including Hong Kong, Singapore and Dubai.

Sri Lanka was ranked 89th out of 160 countries in the World Bank’s 2014 Logistics Performance Indicator (LPI). Notably, Sri Lanka scored 2.91 on competence and quality of logistics services, compared to India’s 3.03, UAE’s 3.5, Hong Kong’s 3.81 and Singapore’s 3.97. This indicates a need for Sri Lanka to improve the quality of its logistics services, as well as a requirement for greater investment in “hardware” - ports, roads and railways.

The participation of foreign logistics service suppliers, many of whom could bring in the level of services that meet international standards, is important for the future development of Sri Lanka’s logistics industry. Currently, the permitted foreign shareholding of a shipping agency in Sri Lanka can be up to 40%, while requests for a larger share has to be approved by the Board of Investment (BOI) on a case-by-case basis.

Apart from its locational benefits, Sri Lanka has other advantages likely to appeal to foreign logistics companies. Unlike a number of other developing nations, Sri Lanka seldom experiences port congestion or large-scale industrial unrest. In addition, the relevant costs involved in undertaking international trade in Sri Lanka are cheaper than when carrying out comparable activities among its regional peers. According to the World Bank’s Doing Business Report 2015, the per-container cost for exporting and importing to and from Sri Lanka are, respectively, US$560 and US$690 – much lower than the South Asian average (US$1,923 and US$2,118) and in Mumbai (US$1,120 and US$1,250).

During a HKTDC Research field trip to a Hong Kong-based shipping and logistics services provider operating in Sri Lanka in early 2015, it was pointed out that an increasing number of liner and barge transport companies are moving to the country. This is gradually helping Sri Lanka achieve the economies of scale required to succeed in the logistics industry. APL Logistics, one of the world’s largest logistics companies, for example, has announced it will set up a regional consolidation hub for South Asia in Sri Lanka this year. Its company statement said that the logistics service provider will operate container freight stations, warehouses and other logistics-related businesses in the country. In a similar vein, Hong Kong logistics services suppliers who are considering expanding their business further afield can work with their Sri Lankan counterparts to access the opportunities in South Asia.

Useful Contacts

| Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA) | Tel: (+94 11) 2421201 Fax: (+94 11) 2440651 Email: webmaster@slpa.lk Website: www.slpa.lk |

| The Chartered Institute of Logistics and Transport | Tel: (+94 11) 5657357 Fax: (+94 11) 2698494 Email: admin@ciltsl.com Website: www.ciltsl.com |

| Sri Lanka Logistics & Freight Forwarders’ Association | Tel: (+94 11) 4943031 Fax: (+94 11) 2507577 Email: secretary.general@slffa.com Website: www.slffa.com |

| Ceylon Association of Ships’ Agents (CASA) | Tel: (+94 11) 2696227 Fax: (+94 11) 2698648 Email: info@casa.lk Website: www.casa.lk |

| Shipper's Academy Colombo | Tel: (+94 11) 3560844 Fax: (+94 11) 2874065 Email: enquiries@shippersacademy.lk Website: www.shippersacademy.lk |

| Sri Lanka Shippers’ Council | Tel: (+94 11) 2392840 Fax: (+94 11) 2449352 Email: slsc@chamber.lk Website: www.shipperscouncil.lk |

Editor's picks

Trending articles

The Hong Kong Law Society has initiated a pact to promote international cooperation among Belt and Road economies.

With more than 60 countries covered under China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the rise of cross-border investment and trading is expected to lead to greater demand for professional legal services. The Law Society of Hong Kong has drafted a related agreement called the Hong Kong Manifesto, and in May, signed the pact with 38 legal organisations from 22 countries and regions along the route. As it sets out to promote a coherent model for businesses and trade to follow, the agreement also promotes Hong Kong position as Asia’s centre for professional legal services.

Thomas So, President of the Law Society of Hong Kong, explains how the manifesto was the culmination of work by the Law Society’s Belt and Road Committee, which also explored the role of Hong Kong’s professional legal services under the global development blueprint.

What is the idea behind the Hong Kong Manifesto?

The Belt and Road Initiative will spur economic activity and numerous cross-border investments. Given that the 60 participating economies have different legal systems, the Law Society believes it is necessary to push forward a model to allow corporations and investors involved in Belt and Road projects to trade and negotiate using the same legal language and game rules. At the same time, the Society plans to set up a legal information platform for the Belt and Road Initiative to provide information on basic investments and regulations, as well as local legal advisory services for the Belt and Road countries.

One of the goals of the Hong Kong Manifesto is to harness members’ power to promote legal interaction and strategic cooperation through annual or bi-annual conferences to explore the challenges and opportunities of the Belt and Road Initiative, as well as relevant legal issues for investors. The Society also plans to establish a Belt and Road Lawyers Alliance with the All China Lawyers Association to construct a closer relationship with the lawyers from the Belt and Road countries, and connect with legal professionals around the region through Hong Kong’s platform to grasp opportunities in this development.

How will Hong Kong’s legal sector benefit from the Initiative?

The Belt and Road Initiative involves many large-scale cross-border infrastructure projects and formulation of commercial agreements, which will drive up demand for legal services related to cross-border legal disputes. Many Hong Kong lawyers are experienced in the matter as they have been handling trading and investment-related legal matters in the Chinese mainland and Southeast Asia since the 1980s and 1990s. The only difference is that they were helping overseas investors to handle legal matters in the mainland and Southeast Asia, but this time, the Belt and Road Initiative mainly serves mainland corporations and investors investing in Belt and Road countries.

Whereas it was overseas companies investing in the mainland in the past, the relevant legal matters were handled by Hong Kong international firms. As many of the senior legal experts that have explored their business in the mainland have now established their own firms, many mainland enterprises looking to explore overseas markets will choose them to handle matters for them. This is a coming trend.

Investment projects in the Belt and Road are huge in scale, often involving multiple regions. These international investments require the coordination of professional services up to international standards, including international law and dispute resolution mechanism. The quality of Hong Kong legal professionals are beyond doubt, and along with a well-established legal system and a free market, Hong Kong can assume the role of a hub to handle commercial disputes over Belt and Road investments. Hong Kong follows the common law. Our independent judiciaries, reliable and transparent regulatory mechanisms, the rule-of-law, as well as impartial attitudes, are all recognised internationally.

How can the legal sector best prepare for opportunities arising from the Initiative?

Hong Kong people might not be familiar with the Belt and Road countries and regions. To visit these regions and handle legal matters might not be as comfortable as handling agreements for sale and purchase of property or IPOs. Cultural differences might prove a challenge, but it is truly an experience that is hard to come by.

To promote Hong Kong’s advantages in the Belt and Road Initiative, the government and professional institutions must work together. The Society has developed a good partnership with the Hong Kong Trade Development Council (HKTDC). Through participating in many HKTDC events – including the Belt and Road Summit and SmartHK held in many Chinese mainland cities, as well as In Style • Hong Kong held in Southeast Asian countries – the Society helps promote the advantages of Hong Kong professional legal services and explore a wider market.

In order to pass on the experience and guarantee the professional standards of the industry, the Society plans to apply for government subsidy to run training courses to encourage new lawyers, especially those working in small- and medium-sized firms, to equip themselves, take up the challenge, and welcome the opportunities brought about by the Belt and Road Initiative.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

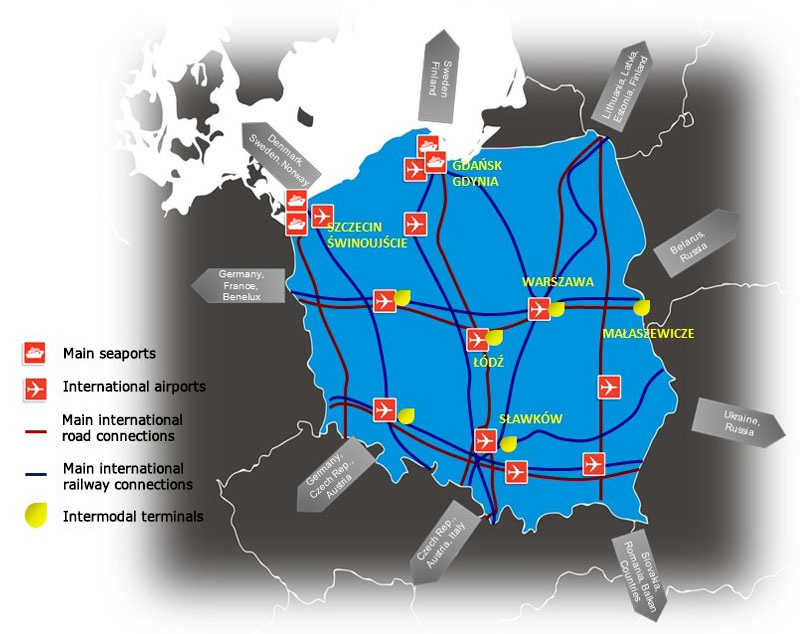

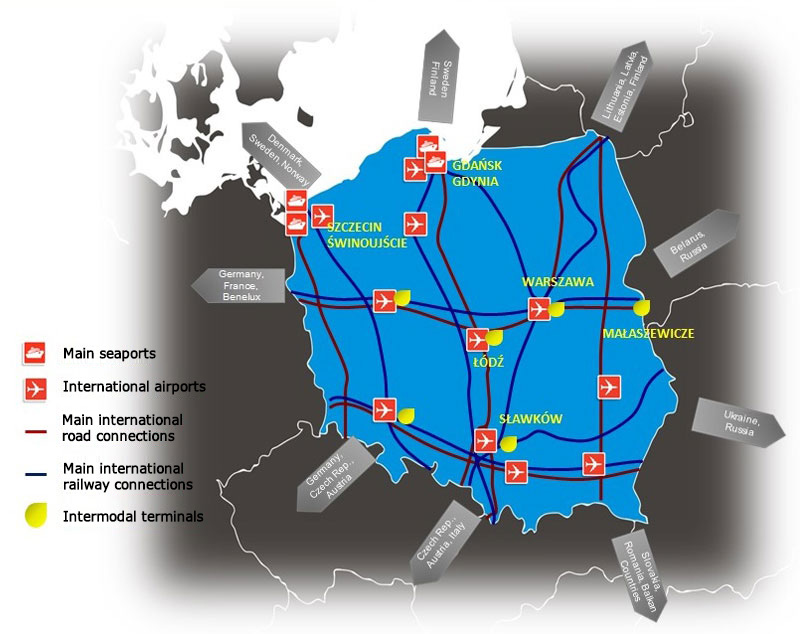

The Czech Republic is home to the biggest airport of any of the newer EU member countries and also to one of the densest railway networks in Europe. As a result, many multinational companies have set up regional logistics centres there. It has some of the best, if not the best, passenger flight connections of any Central and Eastern European Country (CEEC) with the Chinese mainland – and the increased belly cargo capacities, plus the new all-cargo flights between Hong Kong and the Czech capital Prague, have further improved the country’s competitive advantage in the eyes of Asian traders and investors.

Following a boom in the manufacturing and IT sector in recent decades, many Czech enterprises are ripe for development, with their owners considering growing the businesses in co-operation with a reliable foreign partner or selling the businesses outright. Meanwhile, relations between the country and China have improved markedly since Czech President Miloš Zeman assumed office in 2013, and reached a high point following the historic three-day state visit by Chinese President Xi Jinping to the Czech Republic in March 2016.

This has helped to create a more business-friendly atmosphere between the two countries. Some investment deals involving Czech companies have actually been done through Hong Kong, while several Czech businesses are now focussing their attention on Asian markets with their own presence in Hong Kong.

A Crucial Logistic Interface in One Way or Another

The Czech Republic has overcome the disadvantage of being a landlocked country by developing one of the best, if not the best, air transport links with Asia of any of the CEECs. These include excellent connections with the Chinese mainland and Hong Kong. Václav Havel Airport Prague (PRG) now has regular direct passenger flights with three Chinese cities – Beijing, Shanghai and Chengdu.

The belly cargo capacities on these passenger flights, in addition to the all-cargo services between Hong Kong and Prague operated by Slovakia-based Air Cargo Global (ACG) since May 2017 (with a technical stop at Turkmenbashi (KRW) airport in Turkmenistan), have increased the Czech Republic’s ability to handle cargo demand from Chinese and Asian companies on the look-out for ways to take better advantage of the cross-border e-commerce bonanza happening across Europe.

Unlike the other V4 countries, the Czech Republic does not have a common border with the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) area, and so cannot profit directly from serving as a major railway junction for the trans-shipment of containers between the broad-gauge (1,520mm) trains used in former Soviet countries, such as Russia, Kazakhstan and Belarus, and the standard-gauge (1,435mm) trains used in China and the EU.

But the country’s well-connected airport, together with its dense rail network (one of the densest in Europe, after only Luxembourg and Belgium), means the country remains highly competitive and attractive for multinationals such as Foxconn and Amazon looking to set up regional logistics centres for the European-wide distribution of high value-added electronics and the fulfillment of online orders.

It’s not just in creating a logistics hub that the Czech Republic’s railways are important to the country. 200 years of Czech rail industry tradition, coupled with the wave of railway privatisation in Europe in recent decades, has helped to make the country a global leader in rail applications and given it another way to contribute to the expanding rail development between Europe and Asia.

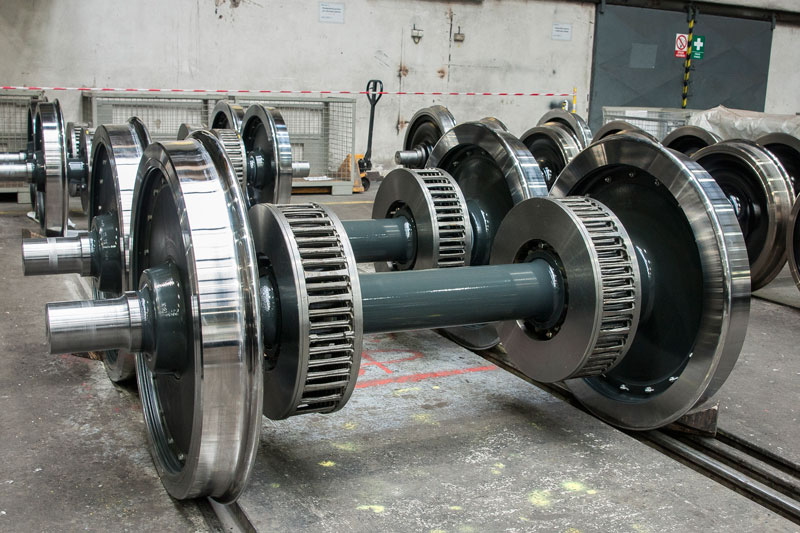

Many Czech companies are heavily involved in the rapid expansion of railway systems worldwide. One such company is the wheelset manufacturer GHH-Bonatrans. As the largest European producer of railway wheelsets and a premium supplier of rail-bound transportation worldwide, GHH-Bonatrans won a MTRC contract to supply wheels for passenger trains in 2015 and established its first Asia presence – Bonatrans Asia Limited – in Hong Kong last year.

Source: Bonatrans Asia Limited

Source: Bonatrans Asia Limited

The company’s tilt towards Asia involves doing business not only with Hong Kong and the Chinese mainland, but with many other Asian countries too, including India and ASEAN. With the Hong Kong office as its sales and service arm for Asia and its manufacturing and servicing facilities in India, GHH-Bonatrans can better promote its new-built and after-sale solutions for clients such as China Railway Rolling Stock Corporation (CRRC) in Asia, which was estimated to account for about 12% of the company’s deliveries in 2015/16.

Czech rail applications suppliers, riding on their price competitiveness, are looking to cash in on Asia’s fast-growing rail network. In China, for example, the amount of high-speed railway mileage reached 22,000km in 2016. While China’s dependency on imported rail applications is actually decreasing with the emergence of domestic versions [1] of high-speed train wheelsets and axles, Czech suppliers which can meet the strictest requirements for train components running at speeds up to 450kph remain a much sought-after partner for Chinese rail operators. Also important is, Czech state-of-the-art technology for noise reduction and rail-wheel contact protection.

The combination of railways which lead the world in terms of safety, reliability, customer service and cost efficiency, and a professional services cluster with extensive global networks and affiliations, has made Hong Kong a natural destination for Czech enterprises hoping to grow with Asian investors under the framework of such regional and/or interregional development initiatives such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Already a conduit for China’s outbound direct investment (ODI), Hong Kong serves as a crucial link in providing not only the important capital flows, but also highly sought-after local knowledge and assurance to new-to-the-market Czech enterprises.

Boom Time for China-led M&As

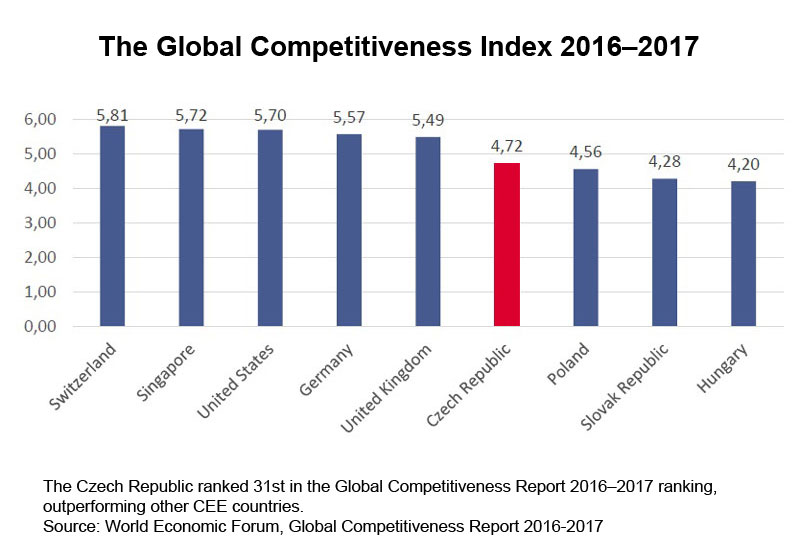

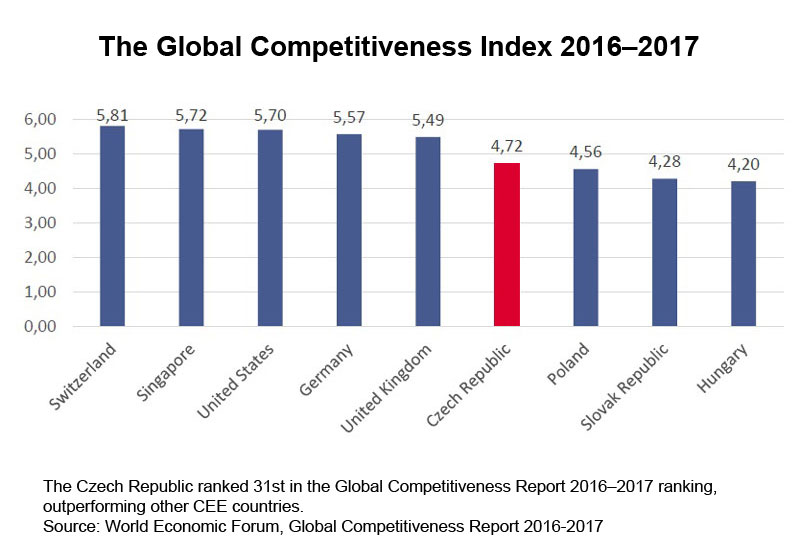

Another trump card of the Czech economy is its strong and highly competitive industrial base. The Czech Republic is the EU’s most industrialised country, with industry accounting for more than 47% of its total economic activity. Its competitiveness ranks higher than CEEC peers such as Poland and Slovakia (see graph), which gives it a significant advantage in the race to attract foreign investment.

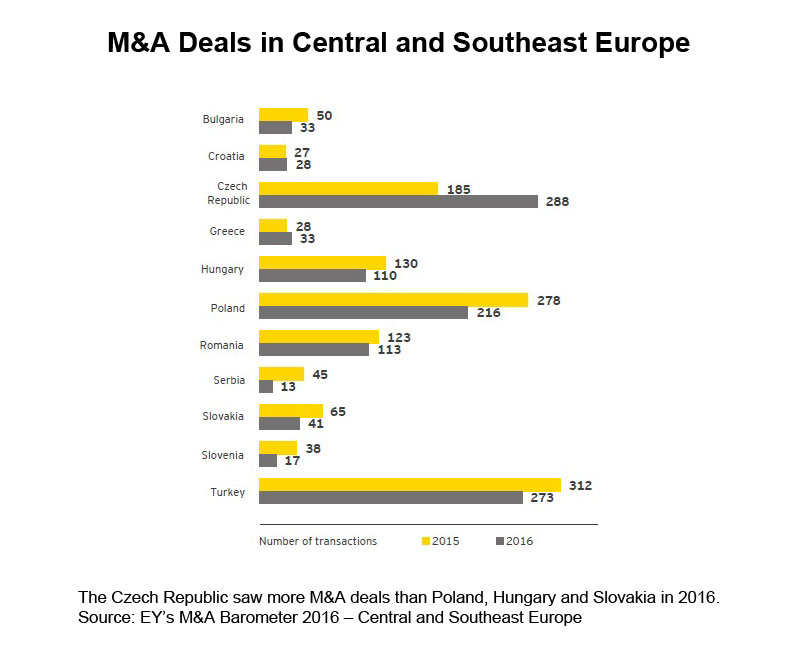

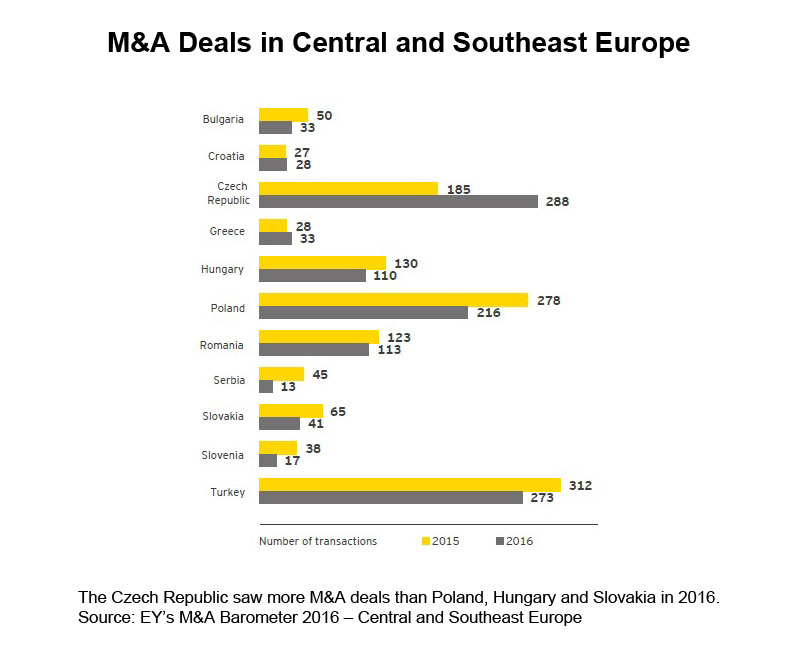

Following a boom in the manufacturing and IT sectors in recent decades, many homegrown Czech enterprises (largely family-owned businesses) are now ripe for scaling up. Some owners are considering development in co-operation with a reliable foreign partner, while others are looking to sell their businesses outright. Such a pool of acquisition targets has made the Czech Republic the region’s most active country in terms of M&A deal volume in 2016, with 288 transactions completed at a total estimated value of US$9.9bn.

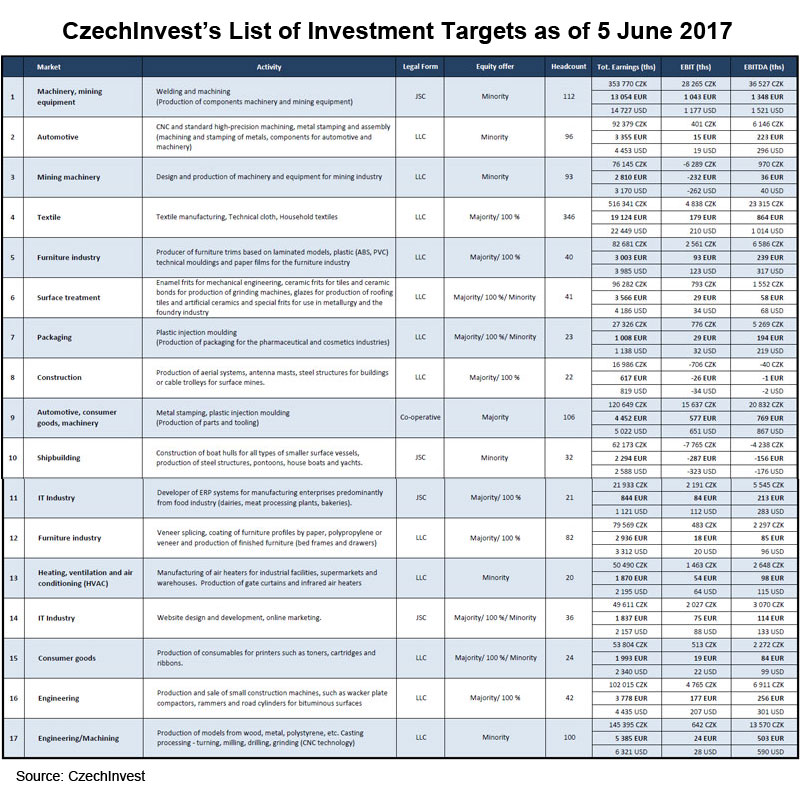

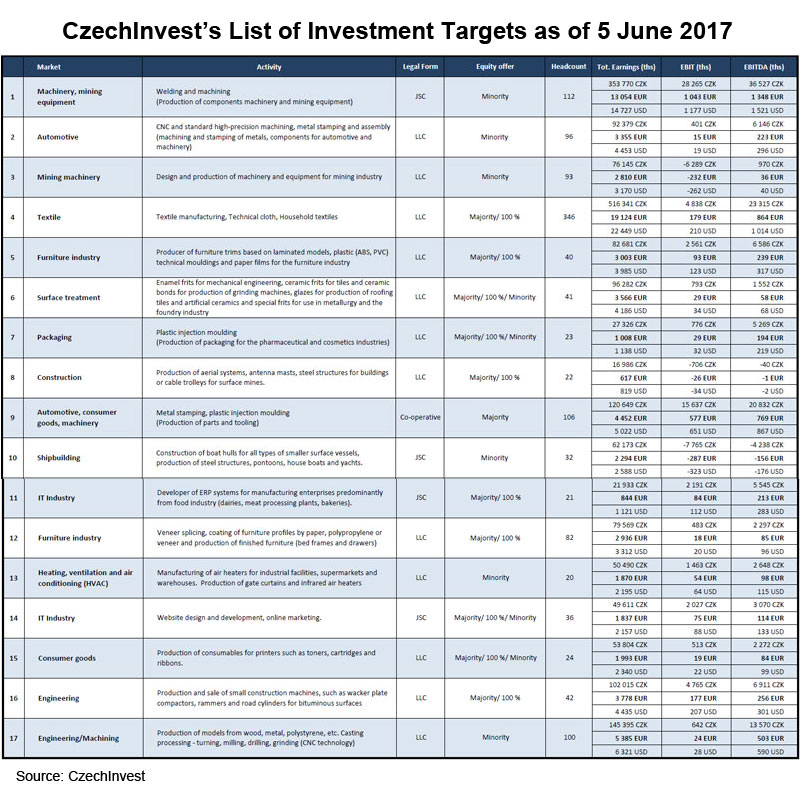

To help Czech companies at the negotiation table, the country’s business and investment development agency CzechInvest, has launched the “CzechLink project” to facilitate qualified investor search and enable the pre-audit project stage. From time to time, a list of Czech companies referred to as “Targets” (companies that are actively looking for a partner/investor for joint venture projects or acquisition) will be published on the agency’s website, while further company profiles can be made available to potential investors, including private equity funds and investment consultants, after signing a non-disclosure agreement.

Also oiling the wheels of the M&A frenzy is the significant improvement in business-friendly Sino-Czech relations. These have taken a marked turn for the better since the arrival in office of Czech President Miloš Zeman in 2013 and reached a high point following the historic three-day state visit by Chinese President Xi Jinping in March 2016. As of March 2017, the total number of domestic Czech companies owned by Chinese investors amounted to 2,101, boasting a capitalisation of about CZK5.5bn (US$0.24bn).

By far the largest Chinese investor in the Czech Republic is CEFC China Energy Company Limited (CEFC China), which is considered a key driving force behind many of these China-led investment deals. The Shanghai-based company has established its second headquarters in Prague and has contributed to a number of sizeable, iconic M&A transactions since September 2015, including the biggest Czech airline company Travel Service, the largest Czech online travel agency Invia.cz, the fifth largest Czech brewer Pivovary Lobkowicz Group, five-star hotels such as Mandarin Oriental Prague and Le Palais Art Hotel Prague, Prague’s largest office building Florentinum, media organisations like Médea Group, Empresa Media and Barrandov Television Group, high-end, metallurgy and engineering company ŽĎAS and even the oldest Czech football club SK Slavia Praha.

Aside from promoting its own investment, CEFC China has continuously been building platforms for Chinese enterprises to invest in the Czech Republic. Following its acquisition of J&T Finance Group (JTFG) in March 2016, which made it the first private Chinese enterprise to own a European bank, CEFC China launched the China-CEE Investment Fund together with Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) in a bid to better bridge China-CEE investment, especially for potential Belt and Road projects.

Hong Kong’s Roles as a Business Conduit

Hong Kong, as a conduit for China’s investment, handling nearly 60% of China’s ODI, is one of the leading Asian investors [2] in the Czech Republic, actively participating in the country’s China-led M&A spree and overall Sino-Czech investment. Some of the China-led investment deals in the Czech Republic have actually been done through Hong Kong. One such notable deal is the acquisition of one of Czech’s biggest DIY and garden equipment firms Mountfield by the Chinese mainland-background, Hong Kong-based Eurasia Development Group in December 2016.

Source: www.mountfield.cz

Some visionary Czech companies are also increasingly tilting using a presence in Hong Kong as a safe and clear-cut gateway to markets in Asia. Examples include famous Czech glass and lighting companies such as Lasvit and Preciosa, which have set up either a regional representative office or holding company in Hong Kong to stay close to both the production base on the Chinese mainland and the rosy residential and commercial property market in Asia. Apart from doing bespoke lighting installations and glass artworks at deluxe hotels, upscale office buildings and premium residences, some of them use Hong Kong as a test bed to ascertain the feasibility of building a bigger foothold in Asia.

Effective since 24 January 2012, the Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement (CDTA) between Hong Kong and the Czech Republic has afforded Czech companies greater certainty and transparency in planning their investment and expansion activities with the involvement of Hong Kong. Thanks to the tax flexibility, Lasvit, which runs a holding company in Hong Kong to oversee its sales and projects in Asia, has worked with the luxurious department store Lane Crawford to introduce its household retail collections.

As a duty free port with efficient logistics and transparent regulations, Hong Kong’s strong position as a centre of trade and proximity to China’s high-value manufacturing base has made itself a strong choice for Czech companies such as GHH-Bonatrans, Lasvit and Preciosa which are looking to showcase their technology and find prospective investors to turn up-and-coming business ideas into reality. This role goes hand-in-hand with buoyant Sino-Czech investment and is further sharpened by Sino-CEE co-operation through the BRI and 16+1 format.

[1] For instance, Taiyuan Iron and Steel (Group) Co., Ltd. (TISCO) produced its first batch of China’s homemade wheelsets and axles in 2014 and completed the necessary tests in 2016.

[2] Hong Kong, holding an FDI stock of US$23.7 million as of end-2015, ranked 7th on the list of Czech Republic’s inbound foreign investors from Asia, trailing South Korea, Japan, the Chinese mainland, Singapore, India and Thailand.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

The Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway is the latest beneficiary of China's African investment programme, with the BRI set to ensure that the number of such projects is set to increase, but are China and Africa's agendas truly compatible?

Djibouti is among the tiniest of all of the African nations, while Ethiopia has long been considered the economic powerhouse of the Horn region of East Africa. Both, however, are clear beneficiaries of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China's massive international infrastructure and trade development programme.

While Djibouti may be diminutive, its port packs a punch, occupying, as it does, a strategic position straddling the entrance to the Red Sea. The country also has a substantial military presence, including the largest American military base in Africa. By contrast, Ethiopia, a nation with the second-largest population on the continent, is a true regional economic bright spot.

These two countries, although markedly different, have now been linked by the Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway, a project largely realised through Chinese engineering and investment. Officially opened in October 2016, Africa's first cross-border electric railway was built by the China Railway Group and the China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation, while most of the US$4 billion financing came from the Exim Bank of China.

The new 750km railway provides a much improved import-export corridor for landlocked Ethiopia. Most significantly, it slashes the seven-day road-freight journey from Addis Ababa to the port of Djibouti to just 10 hours. The outcome of a strategic partnership between China and Africa, the rail link is viewed as an integral part of the BRI.

More recently, in June this year, another China-funded/managed project, the Mombasa-Nairobi Line, went into operation. The 485km line is actually phase I of a much bigger project – a $14 billion standard-gauge railway network that will eventually extend from Kenya on to Uganda then to Rwanda.

Once completed, it is hoped that this network will open up many of the landlocked East African markets to Chinese manufactured goods via the port of Mombasa. It is also anticipated that it will improve the supply chain for African mineral commodity exports, resources that China increasingly relies upon.

The two rail projects are just the latest in a long line of engineering initiatives that have seen China establish a substantial presence in Africa. Back in the 1970s, China built the Tazara Railway, which connected landlocked Zambia and its copperbelt with the Tanzanian port of Dar es Salaam. At the time, this was China's largest aid project in Africa.

More recently, China's commitment to major infrastructure projects across Africa has formed a key element of its BRI agenda. It is also clear that China is keen to play a major role in Africa's economic development, a policy that will only enhance its commercial presence on the continent.

Acknowledging this, during the 2015 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation Xi Jinping, China's President, committed to a generous US$60 billion package of development assistance for Africa. Much of this was earmarked for investment in several major infrastructure projects, including the new Ethiopia-Djibouti Railway and a series of port upgrades along the East African coast.

Assessing China's game plan, David Monyae, a political analyst at Johannesburg University's Confucius Institute, said: "China has enhanced its role on the continent with a no-strings-attached approach to investment and commercial engagement. This has created the impression that Beijing is ready and willing to support Africa's development efforts."

Other analysts, however, have been more cynical, asserting that the BRI is a means for China to create not only a global trading bloc, but also to establish a "zone of influence". One such commentator, Peter Fabricius, a consultant for South Africa's Institute for Security Studies, said: "Xi may be taking advantage of a fortuitous opportunity to extend China's economic and political influence as a world leader. This could see it capitalising on a moment of American global capitulation under Donald Trump, the notoriously isolationist US President."

Fabricius is not alone in seeing a clear indication that a new international economic order may be emerging. As a sign of this, China recently established a military base in Djibouti, alongside those already leased to several other countries, including the US and France.

Others, however, refute that the BRI projects underway across the continent form part of a clandestine power grab. Instead, they maintain that China's investments in East Africa are purely part of a wider trade network, one intended to improve access to Africa's one-billion strong consumer market. As such, it is thought, they should be seen as a development drive that is looking to nurture joint progress through enhanced trading pathways.

Whether the two – geopolitical assertiveness and an increased global trading network – can be genuinely separated out is something of contentious issue. Either way, as one writer – Peter Bruce, one of South Africa's leading business journalists – said: "Chinese influence in Africa is immense, visible and spreading fast."

For many, the key question is whether what works for China will also work for Africa. The African Union, a body that represents all 55 countries across the continent, is optimistic that it will. It has long made it clear that it is keen for China to partner with many of Africa's infrastructure and technology programmes.

Perhaps going some way to explain the Union's enthusiasm, Greg Mills, a South African economist, said: "Chinese contractors and businesses are willing to go to places and work in conditions that few in the West would contemplate."

Made in ChinAfrica

It's not just infrastructure deals, however, that are attracting Chinese investors to Africa. According to the World Bank, an estimated 86 million low-skilled manufacturing jobs are set to be outsourced from China, a consequence of the rising cost pressures caused by higher wage expectations. Ultimately, it is expected that Africa will be the primary beneficiary of this shift in labour demand.

Assessing this likely change, Mills said: "Low-tech, high-labour manufacturing cannot be done virtually and, as China moves up the development scale, Africa can realistically hope to meet this demand."

One sector where such a process is underway is the textile industry, with China having relocated some production facilities to Africa. In particular, China has invested heavily in several large manufacturing projects in Ethiopia, with the East African country set to become the continent's garment manufacturing hub.

Ethiopia is already one of Africa's fastest-growing economies, with the country having pursued a policy of deliberately keeping labour costs low in order to create a competitive advantage. One industrial park, near Addis Ababa, the nation's capital, now houses some 80 Chinese textile firms, all attracted by low or zero tariffs and cheaper labour – comparative industry wages are 15 times lower in Ethiopia than in China. The Huajian Group, a Zhejiang-based footwear manufacturer, has also invested heavily in a large plant in the park, which currently has more than 3,000 employees.

Overall, improved transport infrastructure – much of it funded by China – has led to manufacturing efficiency improving across Africa. Once landlocked Ethiopia, for example, now has direct access to a port following the opening of the Addis-Djibouti Line.

It should be no surprise then that several other African countries, notably Morocco, South Africa, Cameroon and Togo, are now said to be angling for Beijing's attention. Given that Chinese companies have already created some 600,000 jobs across Africa, it is pretty much inevitable that every country on the continent would look to capitalise on the possible spoils of the BRI.

For its part, China clearly believes that outsourcing some of its manufacturing requirements will help make certain African countries more self-sufficient. The naysayers argue, however, that China is taking advantage of cheap labour, demonstrating that it's indifferent to the repressive regimes and poor governance that characterise many of its partner countries across Africa.

Despite these concerns, it's indisputable that Africa needs to create a larger manufacturing sector if its economies are to achieve sustainable growth in a global environment where falling commodity revenues seem a long-term reality. It is also clear that China is looking to capitalise on this need.

Ultimately, as with all other investors, China wants to ensure it is getting a good return on its capital, a policy that is more than apparent in its approach to its African infrastructure projects. Highlighting this, Bruce said: "China does almost no work in Africa from which it does not derive some form of benefit, either political or economic."

As was the case with China several years ago, Africa is now keen to participate more fully in the globalised economy. For many, if the BRI can help boost development across Africa and drive economic activity, then that can only be a positive for the continent.

Mark Ronan, Special Correspondent, Cape Town

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Fung Business Intelligence

With a joint communique signed by the attending government heads and an extensive list of 270 deliverables, the first Belt and Road Forum (BRF) concluded fruitfully in Beijing on 15 May. Featuring the theme ‘Cooperation for Common Prosperity’, the two-day forum drew around 1,500 delegates from more than 130 countries and 70 international organizations, including 29 foreign heads of state and government.