Russia

The Russian economy has been undergoing a wave of diversification over the past decade to reduce its dependency on oil and gas. This has seen its government try to improve the climate for investors through generous incentives and huge infrastructure projects. In a classic win-win situation for both Russia and China, most of these projects are complementary to those that come under the scope of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This potentially creates a whole new world of opportunity for Hong Kong investors and professional service providers.

Bridging the FDI Funding Gap

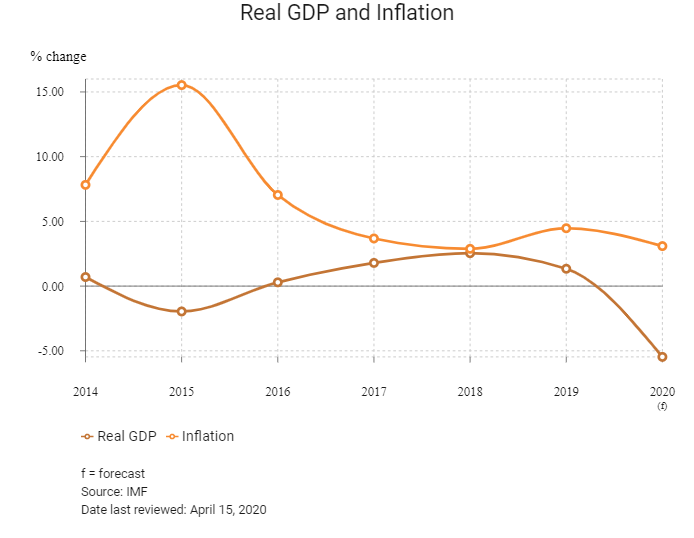

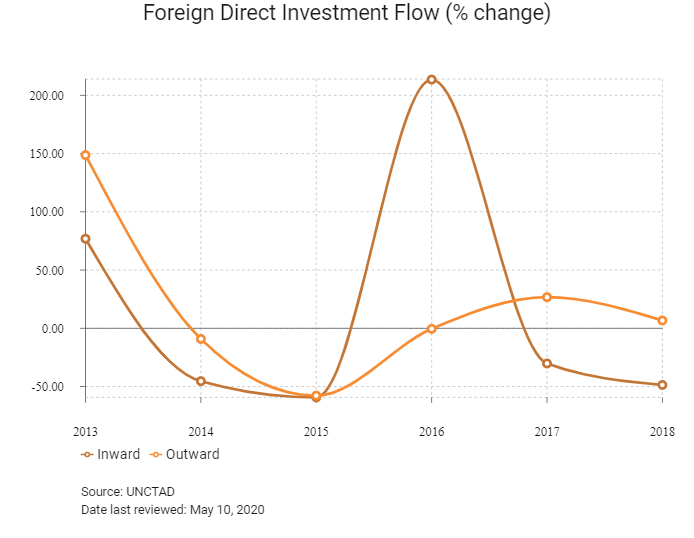

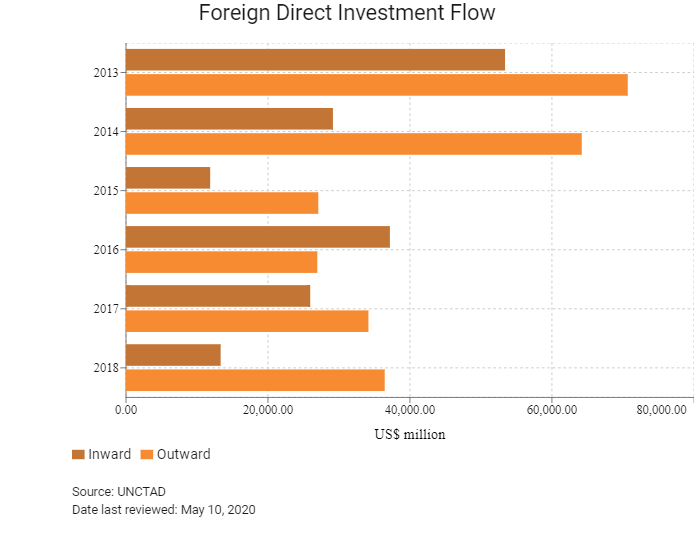

The double blow of the oil and gas price crash and the imposition of international economic sanctions sparked a crisis in confidence in the Russian economy on international finance markets. It led to a huge sell-off of Russian assets, a staggering depreciation of the Russian ruble and a subsequent recession in which real GDP growth fell from a yearly average of more than 3.5% between 2011 and 2013 to -2.8% in 2015 and -0.2% in 2016.

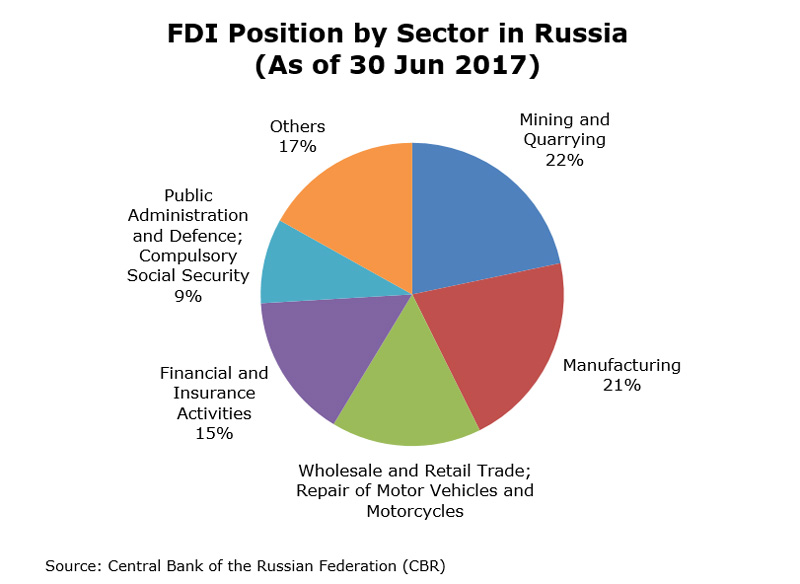

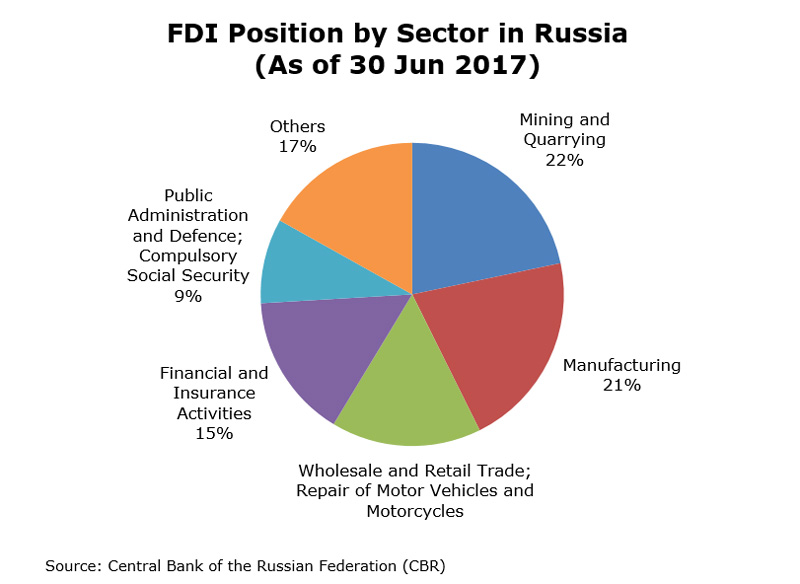

While the crash and sanctions had the effect of bringing the Russian economy to a shuddering halt, they also led to an acceleration of the pace of economic diversification and reform. Although mining and quarrying remains the most popular sector for foreign investment in Russia, with a 22% share of the country’s total FDI inflows as of mid-2017, the combined non-energy sectors now account for more than half the nation’s FDI. Manufacturing (21%), wholesale and retail trade (16%) and financial and insurance activities (15%) are becoming increasingly popular with global investors.

To restore investor confidence and alleviate the effect of Western sanctions, the Russian government has put in place new measures and reforms designed to attract investment. These include the privatisation of state-owned businesses, the provision of cheap bank credit to SMEs, digitising and streamlining government services and boosting strategic state-assisted investment in sectors such as high-tech industries by developing new techno and industrial parks and upgrading existing ones.

The staging of the 2018 FIFA World Cup in June/July 2018 should help improve the nation’s international image and raise global awareness of the various investment possibilities available over its vast land mass. Russia is also supporting the BRI and is ready to actively participate in its implementation.

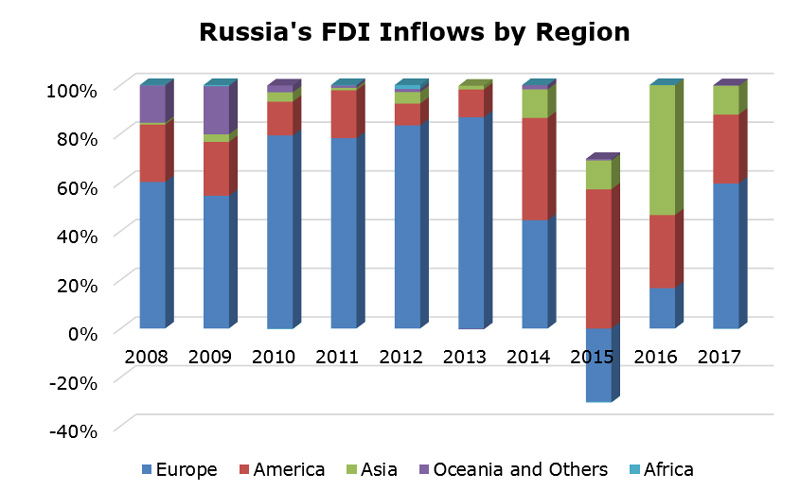

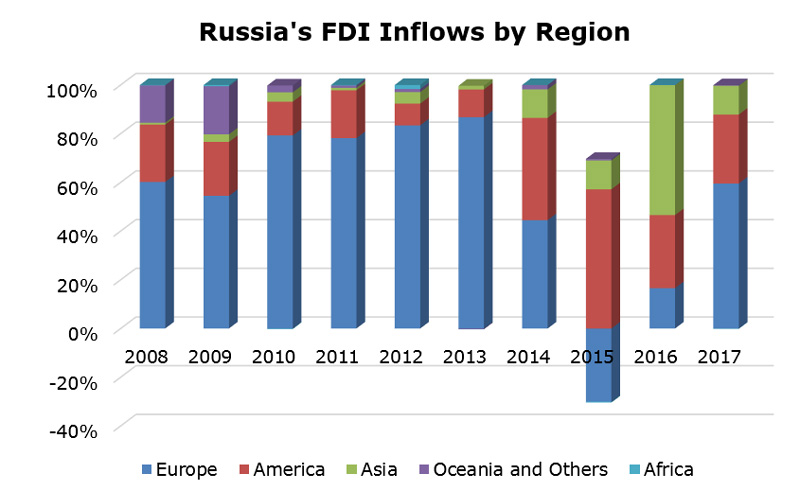

The international sanctions on Russia, such as asset freezes and travel bans on senior Russian officials and oligarchs with ties to President Vladimir Putin, have been led by the West, mainly the US and the EU. As a result, Russia has seen a significant fall in FDI from the EU, particularly between the second half of 2014 and the first quarter of 2016. This downward trend, has, however, been offset by FDI inflows from Asia, which once soared from US$595 million in 2008 (less than 1% of the total FDI inflows in Russia) to US$17.4 billion in 2016 (more than 53% of the total). This trend has continued despite the sharp rebound in FDI inflows from Europe in 2017, a time when Asia still accounted for 12% of the country’s total FDI inflow. Ultimately, this had helped Russia diversify its FDI sources beyond its established European investors.

With few Asian countries supporting the economic sanctions imposed by the US and the EU, the continent has become a crucial source of investment for Russia. According to figures from the CBR, Singapore was the largest Asian investor in Russia in 2017, with an FDI inflow of US$2.4 billion, followed by mainland China (US$573 million), Kazakhstan (US$205 million) and Hong Kong (US$136 million).

Source: CBR

Strong Sino-Russian Ties

The close relationship between China and Russia serves as a solid foundation for the interplay of Russian and BRI investment projects. China does not support the international economic sanctions on Russia, and is actively investing in various sectors of the Russian economy.

An indication of this two-way economic co-operation is the inclusion by Russia of the Chinese yuan or Renminbi (RMB) in its foreign exchange reserve since the end of 2015. Furthermore, in March 2017, the CBR gave its approval to Chinese bank ICBC becoming the official RMB clearing bank in Russia. ICBC is the only Chinese bank with institutions in both Moscow and St. Petersburg which holds brokerage, dealership and depositary licenses.

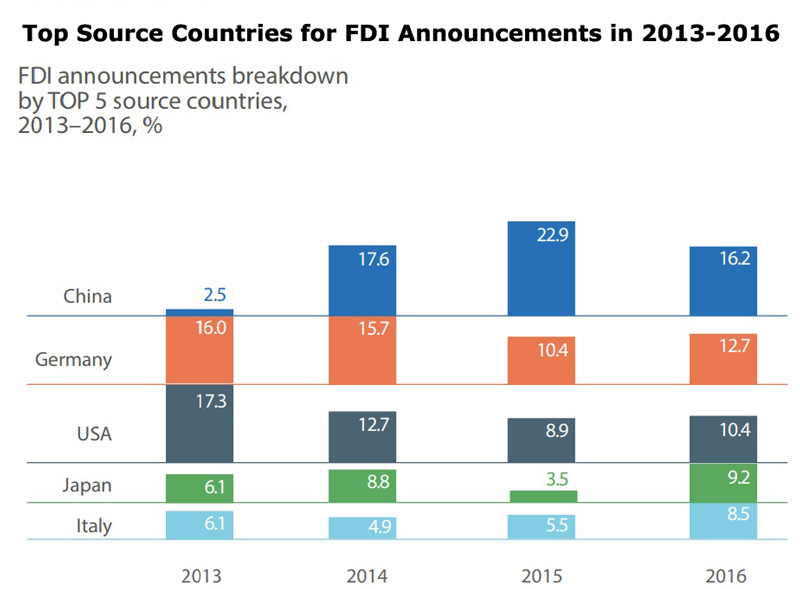

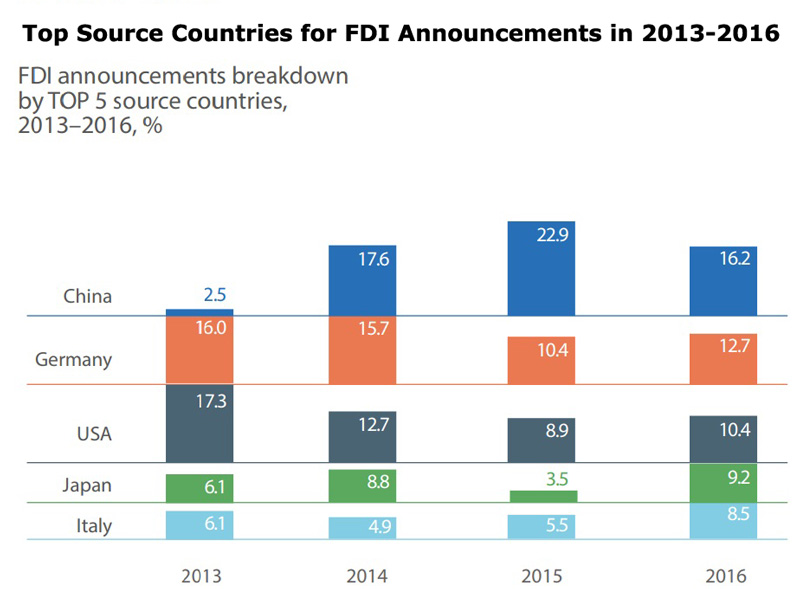

These developments, together with the presence of private Chinese business ventures such as China Business Centre in St. Petersburg and the emergence of key joint investment funds such as the Russia-China Investment Fund (RCIF) by the Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF) and the China Investment Corporation (CIC), have greatly facilitated Chinese investment in Russia and made China the leading source country for Russian FDI announcements in recent years.

Source: Russian Direct Investment Fund

With US$2 billion received in commitments from both the RDIF and CIC, the RCIF has begun some 20 investment projects worth US$1 billion in various sectors since its inception six years ago. One landmark scheme is the Amur River Bridge project. Launched in December 2016, it is the first ever railway bridge crossing the Sino-Russian border. When completed in October 2019, it will create a new trade corridor between north-east China and Russia’s Far East.

Infrastructure projects aside, the RCIF also invests in Russia’s financial and retail sectors. In February 2013, the fund invested in the initial public offering (IPO) of the Moscow Exchange – the largest stock exchange in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). After successful investments in leading Russian retailers like Magnit and Lenta, the RCIF made its first partial exit from an investment in February 2017 when it sold a portion of its stake in Detsky Mir, Russia’s leading children’s goods retailer, and played a significant role in the company’s IPO. This helped to showcase how Chinese investment can help Russian companies grow and scale up to gain access to the stock market.

The RDIF, which is Russia’s sovereign wealth fund with reserved capital of US$10 billion under management, has attracted more than US$40 billion of foreign capital into the Russian economy through long-term strategic partnerships. It has a portfolio of more than 50 investment projects in 95% of Russia's regions, and is estimated to have invested US$26 billion[1] (1.2 trillion rubles) in the Russian economy over the past six years, with almost 60% of its target projects technology-related.

In order to facilitate Sino-Russian investment, the RDIF and the China Development Bank (CDB) agreed to set up a China-Russia RMB Investment Cooperation Fund in July 2017. This created a simplified framework for direct investments with settlements in national currencies, which would invest up to US$10 billion in Russian and Chinese projects, including those under the umbrella of the China-led BRI and the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU).

Other examples of growing Sino-Russian co-operation are the possible launch of a joint investment fund partnership between the RDIF and CITIC Merchant, and the creation of a Russia-China Investment Bank with a wide range of investment banking services designed to strengthen economic co-operation between Russia and China. These include M&A advice, debt finance and capital market services such as IPOs.

Incentives and Infrastructure

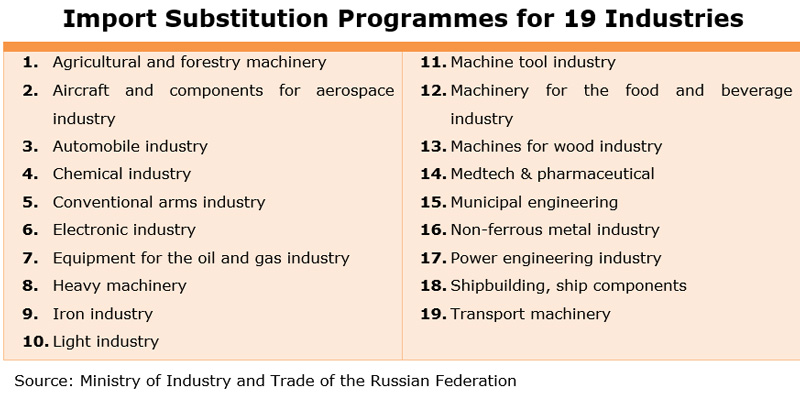

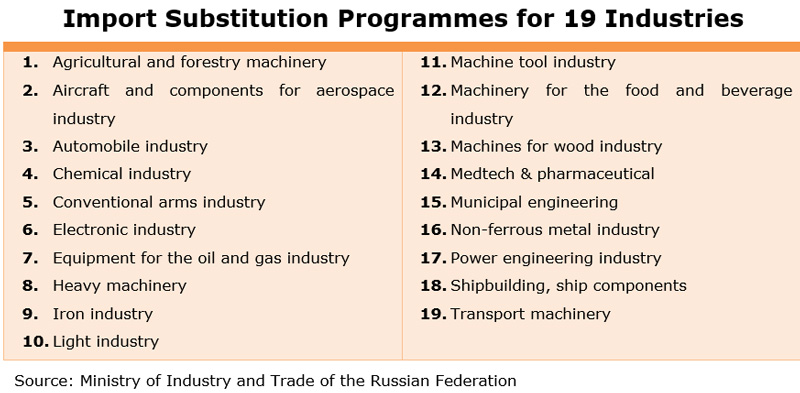

As part of Russia’s new industrial policy to overcome the effect of sanctions and enhance long-term industrial competitiveness, the Moscow government is promoting the gradual substitution of imports by local production. It has developed more than 2,000 individual projects in 19 sectors involving up to 800 selected products and implemented policies such as higher local content requirements to encourage domestic manufacturing.

Some Chinese companies, such as Anhui Conch Cement, Great Wall Motors, Lifan Motors and Van Chen (flour processing and lysine production), are already trying to take advantage of these Russian initiatives. They hope to exploit the opportunities of manufacturing relocation to both capture the 143 million-strong domestic Russian market and also to reach other markets in the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) such as Kazakhstan, Belarus, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan by using Russia as a manufacturing hub.

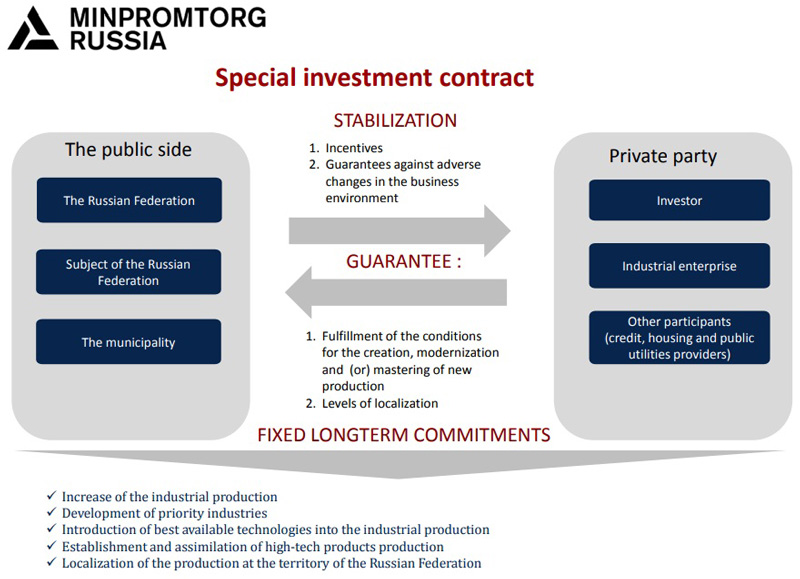

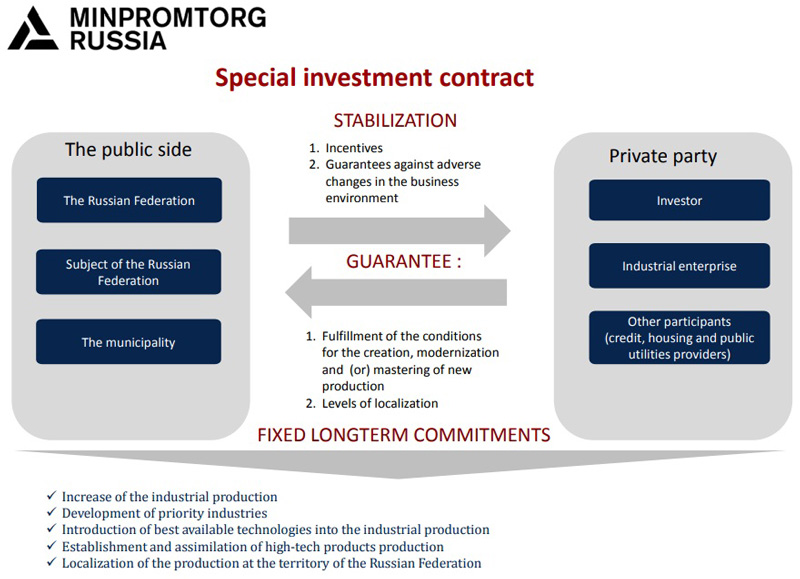

One special incentive measure that has been introduced to try to reduce import dependence in industrial activity is the use of Special Investment Contracts (SPICs). They are designed to encourage (i) the establishment of new (or the upgrade of existing) production facilities; (ii) the localisation of advanced technologies and (iii) the manufacture of products that have no comparable local substitutes. SPICs allow investors to operate under favourable conditions in terms of taxation, regulation and support guaranteed by the Russian authorities.

Source: Ministry of Industry and Trade of the Russian Federation (MINPROMTORG)

One example of how this is working in practice is Russia’s biotechnology industry. Many international pharmaceutical manufacturers, including some from the Chinese mainland, are exploring how they might take advantage of the import substitution campaign and related incentives such as SPICs – as well as the relatively low operating costs in Russia – to start production there.

Long Sheng Pharma, with its divisional offices in Hong Kong, Beijing and Moscow, have been considering expanding pharmaceutical production in Russia with imported materials from mainland China. Valery Mandrovskiy, General Manager of the company’s Hong Kong office and Chief Representative of the Association of the Russian Pharmaceutical Manufacturers in China, said: “The target of increasing the share of local manufacturing of finished formulations in Russia’s pharmaceutical market from the current 35% to 70% in five years paints a very rosy picture for international producers considering production relocation”.

He added: “By better exploiting Russia’s labour cost advantage over many other production bases, made-in-Russia pharmaceutical and healthcare products can also be highly competitive in international markets”.

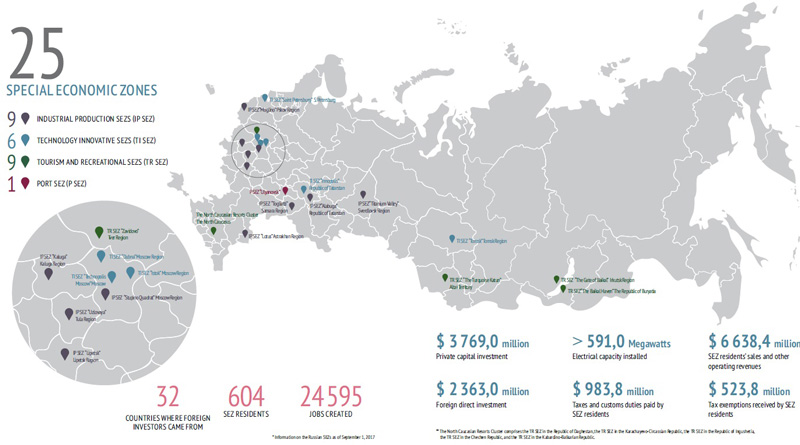

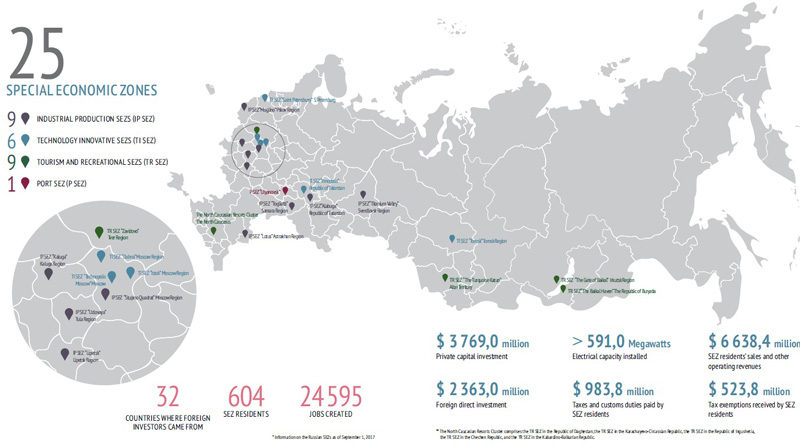

Other opportunities on offer in Russia involve land and physical infrastructure. The country has 25 Special Economic Zones (SEZs) with an array of lucrative incentives designed to bring international investors into the country’s priority sectors, such as the high-tech sector. These SEZs are granted a special legal status by the Russian government, providing companies based in them with tax preferences, free customs arrangements, land plots with ready-to-use infrastructure and free connection to energy resources. All this translates into cost savings of up to 30-40% on average.

Source: Association of Clusters and Technology Parks

In addition to SEZs, the Russian government has been increasing its efforts to develop industrial parks across the country, doubling the number from 80 in 2013 to 166 in 2017. Mostly created by local administration or private entrepreneurs, these industrial parks are well-equipped with the necessary industrial, transport, warehousing and administrative infrastructure for manufacturing. As of 2017, 275 foreign companies from 27 countries/economies (including 8 from China) were operating localised production in these industrial parks.

PPP Projects Seeking Foreign Partnership

When it comes to mega infrastructure projects, Russia has a long history of developing projects on a private-public partnership (PPP) model with local and foreign investors. One of the forerunners in the use of PPP projects, the St. Petersburg City Administration relies on PPP to deliver mega-sized projects while adopting global best practices.

Successful examples include the US$5 billion Western High-Speed Diameter (WHSD) – the first urban high-speed toll highway in Russia and one of the world’s largest PPP projects in the field of road construction – and the St. Petersburg Pulkovo Airport (LED), the only airport in Russia developed on a PPP basis.

The WHSD enhances transport connections between the regions of St Petersburg and provides a crucial link to the new deep-water port of Bronka, situated on the city’s outskirts on the Gulf of Finland. As such, it is vital to the city’s attempts to strengthen its status as a regional logistic hub in CEE.

Pulkovo Airport, one of the largest and busiest air terminals in Russia and Eastern Europe, is run by the Northern Capital Gateway (NCG) consortium – an international group made up of Russian, Greek and German companies and banks. It has the contract to manage and develop the airport on a 30-year operating lease that runs until 30 October 2039.

Russia’s project developers are now actively looking at different PPP models that could be prove more attractive to international investors in other countries. For example, Chinese investors usually prefer build-transfer (BT) projects rather than build- operate-transfer (BOT) or build–own–operate–transfer (BOOT) projects.

While transport infrastructure will continue to be a key development area for Russia and the BRI, Russian authorities, especially at local levels, have been paying more attention in recent years to fostering sustainable, inclusive social and economic development. This includes the development of satellite cities such as the Yuzhny Satellite Town project in southern St. Petersburg.

The only project in Russia where a new multi-functional development (R&D, industry, business and housing) is planned on an area exceeding 2,000 hectares, the “smart city” elements such as energy-efficient transport, intelligent lighting, smart parking and electronic healthcare are central to the Yuzhny development plan.

This is a greenfield project, and as such, the project owner is open to proposals in which Hong Kong investors and professional services providers can act as partners in terms of project financing, urban planning and transport management. The city’s strong connection with mainland Chinese and other Belt and Road investors is also highly appreciated.

Source: START Development

Chinese Investment Success

Given the geographical proximity and close political and economic relations between the two countries, it’s unsurprising that there is already a great deal of successful Chinese investment in Russia. The US$1.3 billion-plus Pearl of the Baltic Sea project in the southwest of St. Petersburg – a multi-functional residential and commercial complex for more than 30,000 people, financed by the Shanghai Industrial Investment Company (SIIC) – is to date China’s largest foreign non-energy development project in the country.

The Hua Bao International Investment Company, formed by Russia’s Hua Ren Invest Ltd and China’s Shandong Dongbao Group, is reportedly implementing a number of investment projects, including the development of a convention and exhibition centre and an industrial park targeting companies from China, Russia and other Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) member states such as India, Pakistan and Central Asian countries.

These projects provide solid building blocks for Chinese investors looking to achieve greater success in the Russian market. One area where this may prove crucial is the Arctic, which is becoming increasingly globally significant given its strategic and economic importance, especially as regards scientific research, environmental protection, sea passages, and natural resources.

China’s Arctic Policy White Paper, released in January 2018, sets out Beijing’s aim of creating greater collaboration with other Arctic and near-Arctic states such as Russia. The objectives are to build a “Polar Silk Road” as a shorter alternative to existing China-Europe voyages via the Suez Canal, to participate in the exploration for and exploitation of oil, gas, mineral and other non-living resources, to conserve and utilise fisheries and other living resources and to develop tourism.

A Greater Role for Hong Kong

As its economic recovery continues to gather steam and the anticipated World Cup-related spending spree kicks in, Russia’s international image may well be bolstered somewhat, while the global profile of several of its lesser-known cities is also certain to be raised.

In 2017, Russia was Hong Kong’s eighth most important European trading partner, having placed orders for a record US$2.8 billion worth of goods. With the Russian economy’s upward trend set to continue, its trade with Hong Kong will almost certainly grow. As an early indicator of this, in the first five months of this year, trade between the two enjoyed growth of 84%, which breaks down into a 91% rise in Hong Kong’s exports to Russia and a 61% increase in imports from Russia to Hong Kong.

With Western sanctions still in place and European and American investors remaining reluctant to commit to any Russia-based projects, it is highly likely that those looking for backing for new initiatives within the country will seek to make wider use of Hong Kong as a fund-raising platform and as a means of striking deals within the wider Asian capital pool. The help of Hong Kong’s professional service providers is also expected to be sought out with regard to advising upon, executing and managing future projects within Russia, particularly with regard to infrastructure development, finance, logistics, information technology, environmental protection and urban planning.

Among the key elements that paved the way to greater Hong Kong-Russian economic collaboration was the early 2016 signing of a Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement (CDTA) between the two, which then came into force in the July of the same year. At around the same time, a further boost came when the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEx) approved Russia as an acceptable jurisdiction of incorporation for listing applicants. At present, an Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement (IPPA) is also being negotiated between the two. Once signed, it is believed, this will optimise the synergy between the two trading partners, while also offering greater protection to both Hong Kong and Russia-based investors.

[1] According to the average RUB/USD exchange rate between 2011 and 2017

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Russian Post records its busiest ever month, a testament to the level of China-Russian cross-border e-commerce.

Russian Post handled 38 million international parcels in March this year, an all-time record for the state-owned mail carrier. This surge in deliveries is at least partly down to the success that two relatively new China-serviced e-commerce platforms – Joom and Pandao – have had in penetrating the Russian market.

The March record easily exceeds the highest level of throughput previously recorded by the carrier. During the immediately pre-Christmas period, traditionally the busiest few months for postal services the world over, Russian Post had previously hit a high of 30 million packages in a month, well short of its March total.

Tellingly, of the 93.7 million parcels handled by the service in the first three months of 2018 – a 35% increase over the same period last year – only some 900,000 were outbound from Russia. This is, again, a clear indication that cross-border e-commerce deliveries largely account for the carrier's package-handling spike.

The contribution of Joom and Pandao to these record figures should not be underestimated. While AliExpress, the Hangzhou-based e-commerce giant that has been active in Russia since 2015, operates its own logistics service, the two newcomers have been almost wholly-reliant on Russian Post for almost all of their deliveries.

Again, unlike AliExpress, both Joom and Pandao are ostensibly Russian businesses, even though the vast majority of their vendors are China-based. In the case of Pandao, it was launched by Mail.ru, Russia's longest-established internet business, in September last year.

Following an intense period of promotion, its user base grew from just 400,000 in November last year to 5.5 million in the March of this year. It now claims to process 370,000 orders a day, a development some see as down to the promotional clout of Mail.ru, which is second in online popularity only to Yandex.ru among Russian consumers.

With the two new players only adding to the flood of e-commerce purchases transiting from China to Russia, with AliExpress and JD.com taking the lead here, a number of new delivery routes have opened up over recent years. These include overland pick-up points in Heilongjiang and Jilin, which are serviced by a growing fleet of Russian trucks, as well as the Xinjiang and Kazakhstan dry-ports, both of which boast state-of-the-art trans-shipment capabilities and ready access to the customs facilities of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), the five-nation trading block that counts both Russia and Kazakhstan as members.

For Hong Kong businesses looking to break into the Russian market via e-commerce, however, the national carrier remains the preeminent choice. As well as offering access to other EEU member states, it also provides a cash-on-delivery service via its Post Bank network, a facility that has proved hugely popular among Russia's less technically-adept online shoppers. In another plus, Post Bank also has the facility to process Union Pay transactions in both roubles and RMB.

As an alternative to Russian Post, Kazakhstan Post – better known as KazPost – has some potential. At present, however, it lacks its own consolidation centre in Asia, a shortcoming that puts up its costs while slowing down its delivery time. It is, however, believed to be in negotiations to remedy this by establishing just such a facility in one of China's coastal cities. With KazPost's ambitions likely to be fuelled by the growing significance of the Belt and Road Initiative, it could be worth keeping an eye on the carrier as a possible future partner.

Leonid Orlov, Moscow Consultant

Editor's picks

Trending articles

The value and power of the Belt and Road Initiative were well illustrated at FILMART 2017 in a Hong Kong joint venture to develop and distribute animated series aimed mainly at children under Russia’s famous Riki brand, said Christine Brendle. The CEO of Hong Kong’s Fun Union, an affiliate of Riki, believed the SAR’s talented people, animation expertise and regional connectivity were “star factors” for success.

Speakers:

Christine Brendle, CEO, Fun Union Limited

Ilya Popov, General Producer, Riki Group

Patrick Frater, Asia Editor, Variety

Related Links:

Hong Kong Trade Development Council

http://www.hktdc.com

HKTDC Belt and Road Portal

http://beltandroad.hktdc.com/en/

GDP (US$ Billion)

1,657.29 (2018)

World Ranking 12/193

GDP Per Capita (US$)

11,289 (2018)

World Ranking 65/192

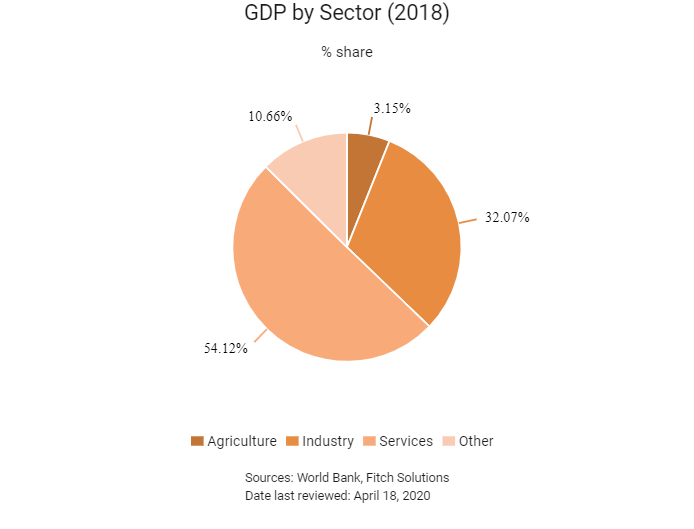

Economic Structure

(in terms of GDP composition, 2019)

External Trade (% of GDP)

49.1 (2019)

Currency (Period Average)

Russian Ruble

64.74per US$ (2019)

Political System

Federal multiparty republic

Sources: CIA World Factbook, Encyclopædia Britannica, IMF, Pew Research Center, United Nations, World Bank

Overview

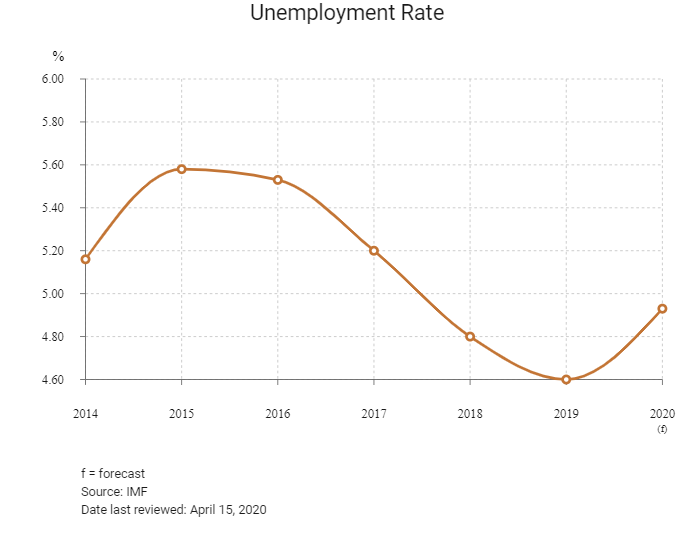

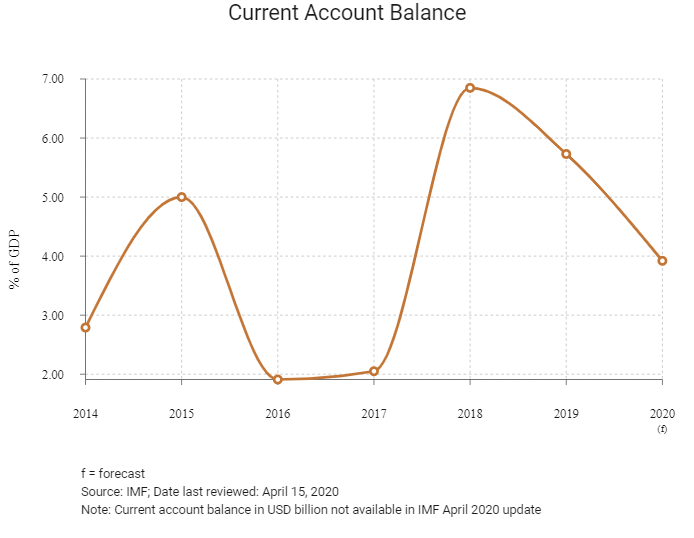

Russia's economic recovery continues amid enhanced macroeconomic stability, improved tax administration, a weaker currency, a conservative fiscal policy and gradual monetary loosening. However, Russia's growth prospects for 2020-2021 remain modest due to Covid-19 and falling oil prices. A return to solid growth will need more private investment, the easing of Western-imposed sanctions and a lift in consumer sentiment. Structural reforms designed to bolster investor confidence could greatly enhance long-term growth prospects. Aided by higher government spending and expansion of retail credit, consumer demand is expected to drive economic growth going forward.

Sources: World Bank, Fitch Solutions

Major Economic/Political Events and Upcoming Elections

October 2018

Novatek announced the discovery of a new gas field in the Ob Bay area, which was estimated to hold natural gas reserves of more than 300 billion cubic metres. The discovery was made via an exploration well in the North-Obsk license area.

December 2018

OPEC, Russia and other allies agreed to further limit oil production in an attempt to boost failing oil prices.

June 2019

The Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev approved the plans for the construction of a toll motorway that will cut cargo shipping time and ease trade between Mainland China and Europe. The USD9.3 billion 2,000km 4-lane highway project, termed the Meridian highway, would stretch from the Russia-Kazakhstan border to existing road networks near the Russia-Belarus border.

June 2019

On June 7, 2019 new legislation was passed in Russia requiring manufacturers of the 735 medicines on the country’s Vital and Essential Drugs List to re-register prices with the Russian Ministry of Health. As part of the re-registration process, prices would be reassessed using external reference pricing methodology. After re-registration, manufacturers will be obliged to reduce prices in line with downwards price changes in reference countries.

July 2019

Construction started on a cableway at the Mainland China-Russia border. The 972m-long cableway would span the Heilongjiang River, known in Russia as the Amur River, and would connect Heihe in northeast Mainland China's Heilongjiang Province with the Russian city of Blagoveshchensk. The project was designed for two-way traffic and each cable coach would have a capacity to carry 80 people. The system would be able to carry six million people annually, with each one-way ride expected to take less than 10 minutes. The cableway was slated to become operational in 2021.

October 2019

The Russian government supported a draft law aimed at capping foreign ownership of major technology companies to 50%-minus-one share, a sharp increase from the 20% initially proposed.

December 2019

Russia's agriculture safety watchdog said it would lift the temporary restrictions on poultry supplies to Russia from a plant in Brazil.

January 2020

Russia's President Vladimir Putin accelerated a shake-up of the country's political system by submitting a constitutional reform blueprint to parliament that would create a new centre of power outside the presidency. In draft amendments submitted to the State Duma lower house, Putin offered a glimpse of how his reforms look on paper. Under his plan, some of the president's broad powers would be clipped and parliament's powers expanded.

February 2020

Russian state lender VTB had finalised the sale of a 55% stake in mobile phone operator Tele2 Russia to state telecoms group Rostelecom. The bank would receive RUB108 billion (USD1.7 billion) from the sale of 45% of Tele2 Russia's shares and also exchange a further 10% of Tele2 Russia's shares for 10% of Rostelecom's ordinary shares.

President Vladimir Putin instructed the government to launch a new investment cycle so that the country's economy could grow faster than the global economy in 2021. He added that he was counting on the joint work of the government and the Bank of Russia to drive the new investment cycle.

March 2020

The government announced a comprehensive economic stimulus package worth USD18 billion to ease the challenges faced by business, consumers and the financial sector due to Covid-19.

Saudi Arabia and Russia, the world’s two largest oil exporters, failed to agree on production cuts to increase global oil prices. As a result, Saudi Arabia drastically decreased the price of its oil, causing the global oil price to drop by about 30%, below Russia’s breakeven level.

Covid-19 lockdowns across various countries resulted in the demand for oil decreasing by about a third.

April 2020

Leading oil producers agreed to cut production by approximately 10 million barrels per day, with milder production decreases set to extend to 2022.

Sources: BBC country profile – Timeline, International Monetary Fund, New York Times, Fitch Solutions

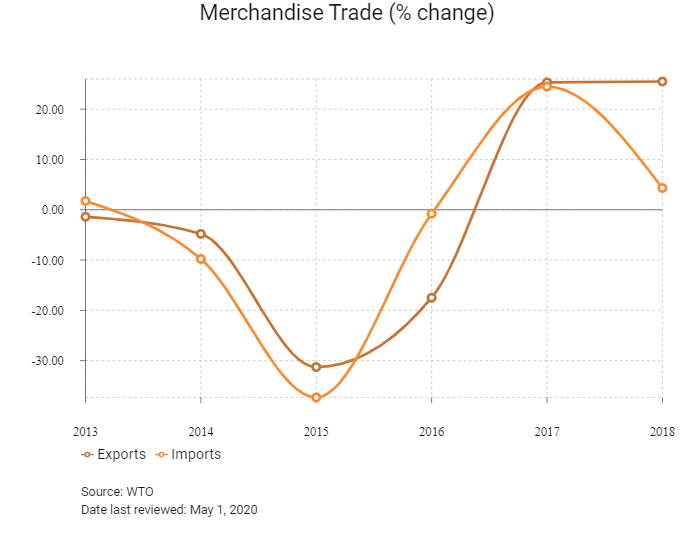

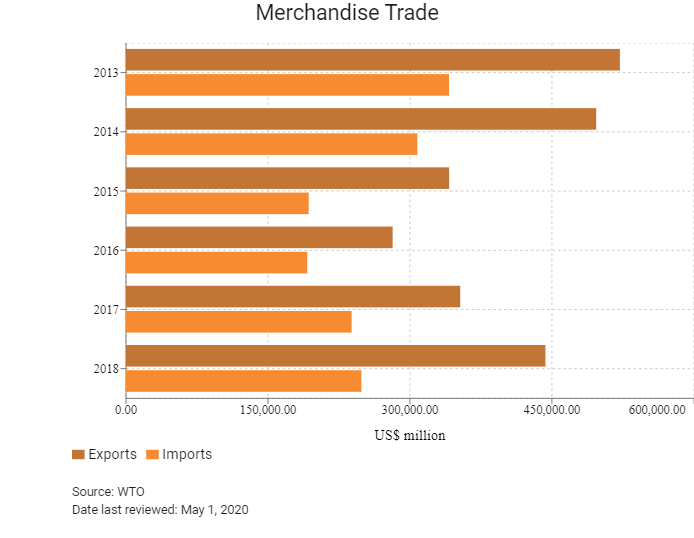

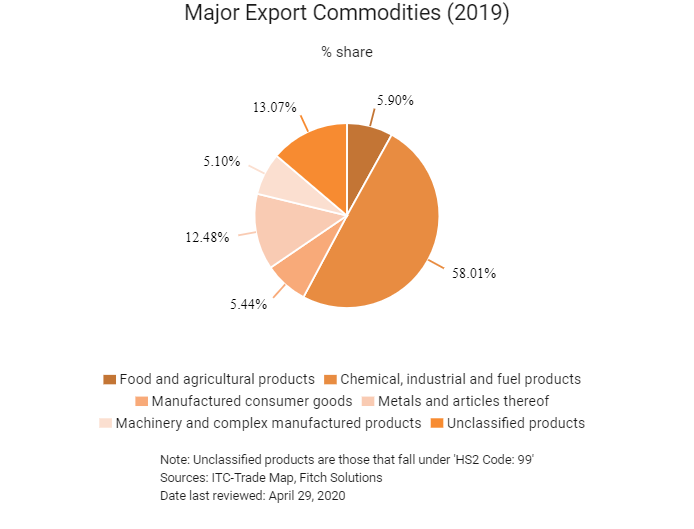

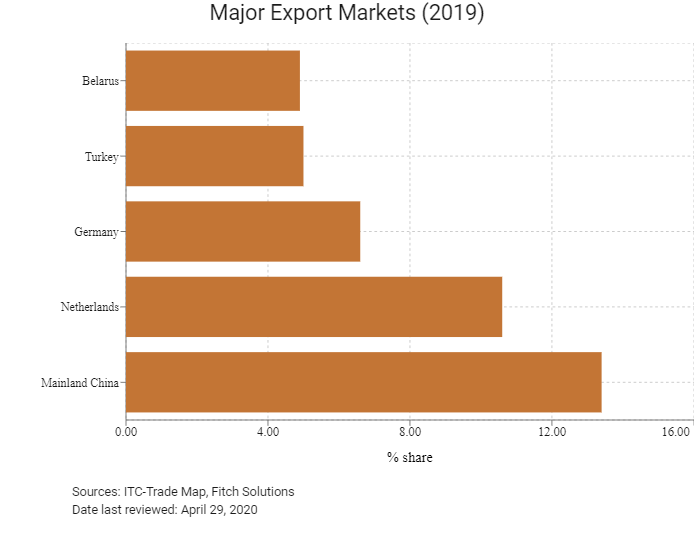

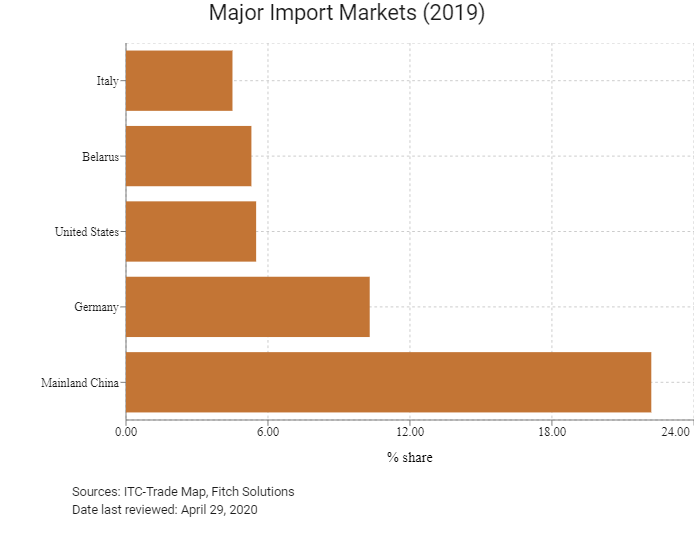

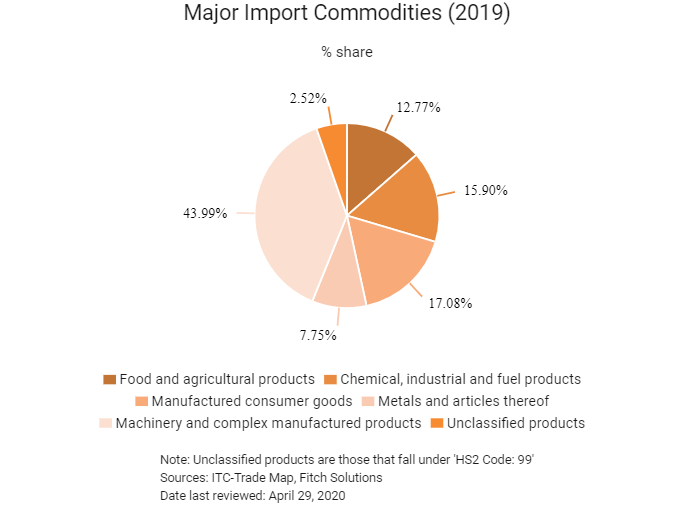

Merchandise Trade

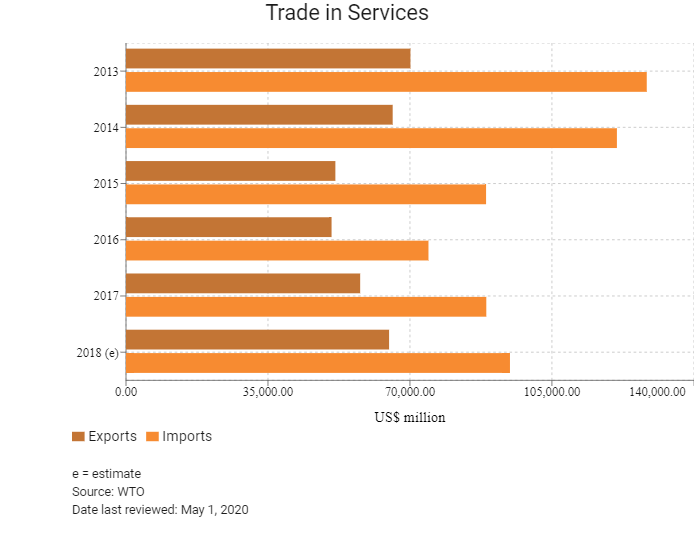

Trade in Services

- Russia and Ukraine signed a programme of economic cooperation in 2011, before the Maidan revolution. The document was planned for implementation by 2020 and provides for enlarging free trade and mutual protection of investments, creating a system of payment and settlement operations and ensuring the free movement of citizens. However in Q118, Kiev announced the cancellation of its economic cooperation agreement with Moscow, marking a further decline in interstate relations.

- The broader concern within Russia's trade profile is the limited diversification away from the country's high reliance on primary sector output – and specifically hydrocarbons. Investors will be dissuaded by the lingering obstacles to trade that stem from the country's stalled transition from a centrally‑planned to a free‑market economy. Although Russia became a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2012, it continues to implement policies and duties which restrict trade freedom and add to the difficulties faced by exporters and importers. While the Russian government, at all levels, offers moderately transparent policies, actual implementation can be inconsistent. Moreover, Russia's import substitution programme often leads to burdensome regulations that can give domestic producers a financial advantage over foreign competitors.

- Russia's trade openness remains encumbered by tight protectionist measures. The average tariff rate remains the second‑highest regionally in Central and Eastern Europe, at 6.3%, driven by the levying of considerable duties on imports of animal products (which average 23.1%), beverages and tobacco (22.1%), clothing (11.7%), transport equipment (8.9%) and manufactures (8.4%). The lowest tariffs are applied to cotton (0.0%) and petroleum (5.0%). Russia's failure to fully commit to WTO guidelines is a feature of its unpredictable trade policies.

- Any import or export transaction equal to or over the value of USD50,000 requires a 'deal passport' authorised by a Russian bank, through which the payment will be processed. Although there are generally no problems with obtaining deal passports, this adds to the bureaucratic obstacles faced by businesses engaged in international trade.

- Import value‑added tax (VAT) is payable to customs upon importation of goods. The tax base for import VAT is generally the customs value of the imported goods, including excise duties. Either the 18% or 10% VAT rate may apply upon the import of goods to Russia, depending on the specifics of the goods. Import VAT may generally be claimed for recovery by the importer, provided that the established requirements for such recovery are met.

- The government's import substitution policies, such as the Food Security Doctrine, cause significant uncertainty for businesses and may result in quotas or increased duties on imports.

- There are various items that fall under the import substitution regime, with certain items of machinery being restricted for import into Russia – such as coal mining machinery – where a special duty rate applies.

- In July 2014, sanctions were were imposed against Russia in a coordinated manner by the EU, the United States, Canada, and other allies and partners. These sanctions were further strengthened in 2018. These sanctions restrict access to Western financial markets and services for designated Russian state‑owned enterprises in the banking, energy and defence sectors. They also place an embargo on exports to Russia of designated high‑technology oil exploration and production equipment as well as designated military and dual‑use goods. Externally imposed restrictions on imports of Western‑borne capital goods have delayed exploration projects in the mining sector especially.

- The Russian government holds significant stockpiles of metal ores and precious metals such as palladium, and restricts the amount of metal that can be exported each year. High entry barriers and substantial regulation will obstruct new, especially non‑Russian companies, from entering the mining industry, which will continue to hinder growth in the sector.

- There are also various export duties and bans imposed on various items, ranging from agricultural products to minerals deemed vital to the domestic economy. Arbitrary tariffs on exports have also been implemented on primary sector commodities in order to regulate prices on the domestic market. For example, in December 2014, a new levy on grain exports was announced, the third such time that exports of grains have been restricted since 2007.

- Following the signing of a package of agreements in November 2009 to establish a Customs Union (CU), Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan began using common external tariffs (CET) in early July 2010 and launched the common economic space on January 1, 2012, enabling free movement of goods, services, capital and workforce between the three member states. A treaty aiming for the establishment of the EAEU was later signed on May 29, 2014 by the leaders of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia, and came into force on January 1, 2015. Following the signing of respective treaties aiming for Armenia's and Kyrgyzstan's accession to the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) on October 9, 2014 and December 23, 2014, Armenia entered the EAEU on January 2, 2015 and Kyrgyzstan acceded on August 12, 2015.

- In August 2016, the Russian government added unwrought lead to the list of goods deemed essential to the internal market. Goods stated on that list may become subject to an export ban to ease internal market conditions. The Russian government has also established a permanent fixed rate of export duties on other ores, such as tungsten ores and concentrates, at 10% of their customs value.

- There are various export duties on ethane, butane and isobutene and restrictions on trade in strategic minerals such as platinum and palladium. Despite rising palladium prices, the Russian government will continue to exert tight control over the amount of palladium supply exiting the country, thus restricting the sector's growth prospects.

- Even within the EAEU, there are export licensing requirements on unprocessed precious metals, commodities, waste, scrap, ores and concentrates of precious metals, as well as on untreated mineral stones.

- Import and export duties are calculated as a percentage of the customs value of the goods (ad valorem) or in euros per unit of measurement of the goods, and/or as a combination of these two rates. In most cases, however, ad valorem customs duties are levied as a percentage of the customs value of the goods. For most Hong Kong‑type consumer products – like garments, household hardware, consumer electronics, timepieces and jewellery – current tariff rates stand at 5%‑20%. On the other hand, export duties are set for a few commodities like oil products, copper, nickel, timber and goods made of these materials. Meanwhile, anti‑dumping proceedings against Hong Kong have been scarce. Only one anti‑dumping measure in place affects Hong Kong goods – specifically imports of cold‑rolled flat steel products with polymer coating.

- The Russian customs tariff classification is based on the Harmonised Commodity Description and Coding System. All goods carried across the country’s customs border have to be declared to customs authorities of Russia. A customs declaration should be submitted within 15 days after the goods are presented to customs authorities. Customs duties, if any, should be paid to the authorities when the goods cross the Russian border.

- Russia has anti‑dumping measures on 42 products from 34 countries. These anti‑dumping measures are implemented by either Russia alone, or by the EAEU.

- Russia has implemented import restrictions on 130 product lines from 65 countries. Most of these product lines fall under the Food Security Doctrine.

Sources: WTO – Trade Policy Review, Fitch Solutions

Multinational Trade Agreements

Active

EEU: The EEU consists of Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Russia. The agreement, which is based on the Customs Union of Russia, Kazakhstan and Belarus, entered into force on January 1, 2015. It was later joined by Armenia and Kyrgyzstan. The union is designed to ensure the free movement of goods, services, capital and workers between member countries. However, trade between the various member states is limited and many customs disputes between member states remain unresolved. Most importantly, Ukraine's exit from discussions following the Euromaidan protests has significantly undermined the prospects for success by excluding what would have been the EEU's second-largest economy.

Partially Active

Commonwealth of Independent States FTA: The Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) is comprised of Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Uzbekistan, Moldova, Armenia and Kazakhstan. The first treaty entered into force on September 20, 2012. CIS states remain key trade partners, but Russia has suspended the application of the FTA for bilateral trade with Ukraine, meaning that barriers have been raised with Russia's largest trade partner within the group.

Awaiting Ratification

EEU-Serbia: The EEU and Serbia signed a FTA on October 25, 2019. The agreement replaces the existing agreements between Serbia and Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan. Approximately 90% of Serbia’s exports to the EEU are destined for Russia. The FTA is expected to increase Serbia’s EEU exports by 50% within the first three years.

Source: WTO Regional Trade Agreements database

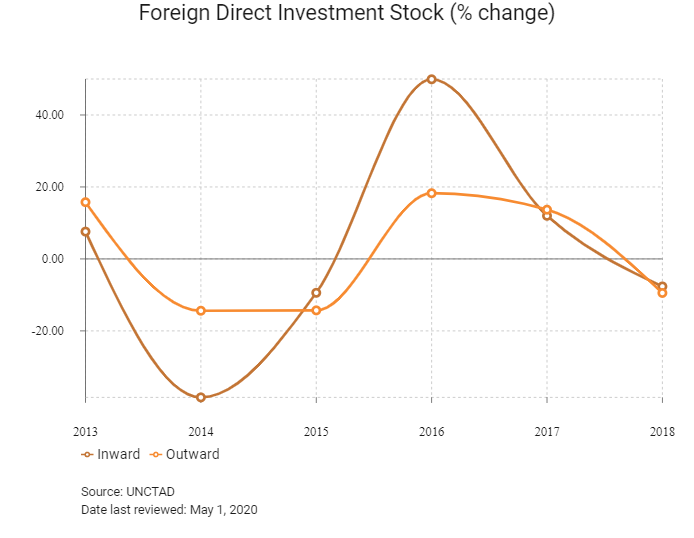

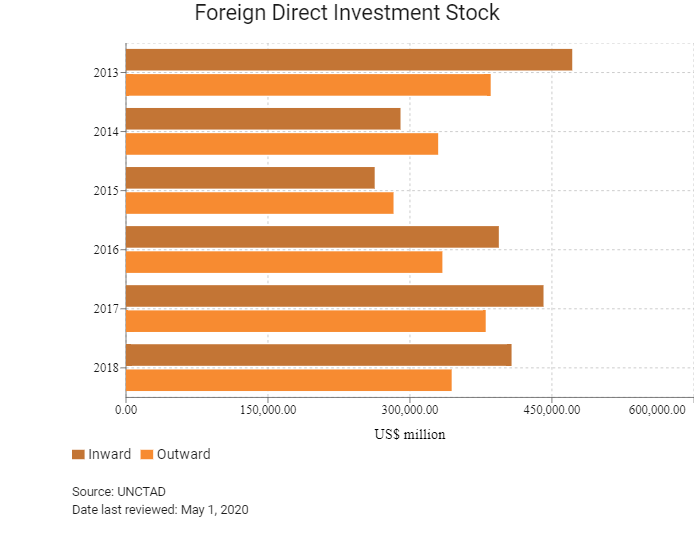

Foreign Direct Investment

Foreign Direct Investment Policy

- To stimulate investment with the aim of diversifying its economy, the Russian government is providing a wide array of incentives for investors developing new products or technology in the energy efficiency, nuclear engineering, space technology, medicine and information technology industries. Major incentives include profits tax/property tax/VAT exemption, reduced social contribution rates, special customs regime and a 150% deduction of qualifying costs for companies conducting eligible research and development activities to reduce profits tax or increase deferred tax assets. Other key sectors for development and investment include pharmaceutical and medical, real estate, innovations and technology, infrastructure, aluminium, iron and steel, lead, platinum-group metals, precious metals, nickel, copper, zinc, coal, telecommunications, transportation, agriculture, food and gas. However, the Russian government continues to impose some restrictions on trade flows and limits on foreign direct investment (FDI) in certain sectors, while state-owned institutions are prevalent in all areas of the economy.

- The North-South Transport Corridor will continue to gather momentum in the coming years, driven by the alignment of geopolitical goals and burgeoning trade ties among the countries along its route. The envisaged transport route, which aims to ultimately link India and Russia via Azerbaijan and Iran, will attract road, rail, and port infrastructure investment and would substantially reduce the time and cost needed to ship freight along a north-south axis.

- FDI is restricted in some strategic sectors, as detailed in the 2008 Strategic Investment Law. These sectors include those involved in the exploitation of natural resources, defence, media and industries in which SOEs have a monopolistic advantage. Any investor seeking to increase shareholdings or gain a controlling stake in any company deemed to be in a strategic sector will require prior government approval, which is not always guaranteed and frequently comes with certain conditions. This prevents large-scale foreign investment in many potentially lucrative sectors, with the law also being arbitrarily applied to some activities that do not initially appear to fall under the description of a strategic sector. This was illustrated in 2012 when internet company Yandex was deemed a strategic asset, limiting foreign ownership in the company. In the extractive industries, government approval is required for foreign ownership above 25%. If a transaction occurs in contravention of the Strategic Investment Law, the companies involved may be subject to harsh penalties, including the complete voiding of the deal.

- A major barrier faced by foreign investors in Russia is the large-scale government presence in the economy through complete or partial ownership of companies in a wide range of sectors. SOEs dominate the market in some industries, notably hydrocarbons (through Gazprom and Rosneft), banking (Sberbank and VTB) and telecommunications (Rostelecom). Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the country began a long and arduous privatisation process which is still ongoing, but the government has maintained an interest in many companies, whether as a minority shareholder or the owner of a 'golden share' (50.1%). Thus, in several instances in which foreign investors have become involved with SOEs, they remain limited to minority shareholding positions. This often leaves them unable to influence company policy and subject to undue control by the board of directors. Competition between private entities and SOEs is also limited in certain sectors where the playing field is tilted in favour of government enterprises.

- Russia's Strategic Sectors Law (SSL) establishes a list of 46 'strategic' sectors or activities in which purchases of controlling interests by foreign investors must be pre-approved by Russia's Commission on Control of Foreign Investment. In 2014, the Russian government expanded the list to include companies, investments and transactions. The SSL includes offshore companies and their subsidiaries, in addition to foreign states, international organizations, and their subsidiaries. The 2017 amendments’ definition of 'offshore companies' includes tax havens (i.e. legal entities incorporated in states or in territories that providing preferential tax treatment and/or do not require disclosure and submission of information when conducting financial transaction).

- Regulations require Russian government approval for foreign firms to invest in strategic sectors and, in some cases, ban majority foreign ownership. Most government initiatives point to a stronger government influence in SOE activities, including placing senior government officials on major SOE boards, dictating the percentage of SOE purchasing that must come from small- and medium enterprises, and requiring Russian-made equipment purchases for government-funded projects.

- In December 2015, Russia amended the federal law 'On the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation', giving the Russian Constitutional Court authority to disregard verdicts by international bodies, including investment arbitration bodies, if it determines the ruling contradicts the Russian constitution.

- In addition to a raft of pro-business reforms introduced by President Vladimir Putin since 2012, which have improved the operating environment, there are a number of incentives offered to encourage FDI. These will vary according to the location of the investment, the amount of capital provided and the type of economic activity. Foreign investors are exempted from the effects of unfavourable changes to legislation (for example, tax hikes or new caps on foreign ownership) for a period of seven years, if they hold more than 25% of capital in a company. A major new incentive introduced in 2014 is an income tax break for companies located in 13 Far Eastern and Siberian regions, which effectively reduces the profit tax rate from the usual 20% levy to 0% for the first five years after initial sales income is received, and to 10% for the following five years. Some regional authorities offer a reduced corporate income tax rate of 15.5%, which is available for both foreign and national investors.

- The most significant incentives and benefits, however, are offered through the numerous special economic zones (SEZs) that are available throughout the country to investors. The zones are divided into four broad categories. These SEZ categories are industrial, technology implementation, port, and tourist and recreation SEZs. These SEZs are all intended to target specific industries, for example shipping and freight transport, hotels and tourist activities, automotive and mechanical engineering, or software and pharmaceuticals. Businesses located in these zones benefit from more efficient bureaucratic procedures, freedom from customs duties, state investment in transport networks and subsidised expenditure on infrastructure. The government also hopes that SEZs will foster the development of sophisticated industrial clusters which enhance technological advances and boost economic growth in particular regions.

- Many industrial regions of Russia offer numerous tax and non-tax incentives and benefits to investors. Regional incentives in the form of reduced tax rates (primarily the given region’s portion of corporate income tax, property tax, and transport tax) are granted to certain classes of taxpayers, typically large investors or entities operating in specific industries.

- As of 2019, movable property is not subject to property tax. Consequently, the issue of correct classification of an asset (movable or immovable) has becomes an important topic for taxpayers. Note that the relevant court practice is not consistent, and Russian lawmakers are working on amendments to the Russian Civil Code that may introduce clear criteria of immovable property.

- Foreign ownership is permitted, with the exception of some sectors designated as strategic. Russia's regulatory environment will continue to restrict foreign investment from entering the country's mining sector. Defence, oil and gas, power, mining, media, transport and agriculture are key sectors affected. Foreign ownership in air transportation, financial services, insurance, media and agricultural land is also restricted to a maximum of 49% ownership. There are significant barriers to entry facing foreign insurance firms looking to tap into the enormous long-term growth potential of the Russian insurance market. Foreign entities considering entry to or expansion in the Russia financial sector will also need to be mindful of economic sanctions imposed by the United States and European Union, which potentially restrict operations over the short-to-medium term.

- On January 30, 2020 the Russian government approved a number of acts concerned with rendering new economic benefits and subsidies to businesses or investors willing to engage in projects in the country's High North. This initiative provides a steady foundation for the introduction of Russia's Arctic strategy until 2035. The main expectations pinned to the initiative are premised on the prospect of creating more than 21 new large regional mega-projects (including the Indiga Port, in Nenets Autonomous Okrug), exploration of large deposits of platinum and other metals in Krasnoyarsk Krai and Murmansk Oblast, and the creation of a full-cycle lumber/timber-producing complex in Arkhangelsk Oblast. These and hundreds of smaller commercial initiatives (to become fully operable within the next 15 years) are expected to result in the creation of 200,000 additional jobs in the region and “make the Arctic attractive to Russian youth and young specialists”.

Sources: WTO – Trade Policy Review, ITA, United States Department of Commerce, national sources, Fitch Solutions

Free Trade Zones and Investment Incentives

|

Free Trade Zone/Incentive Programme |

Main Incentives Available |

|

30 SEZs divided between four broad categories: industrial and production zones, technology and innovation zones, tourist and recreation zones, port zones |

- Exemption from customs duties and VAT on imports |

|

Skolkovo Innovation Centre (Moscow) – intended to foster innovation in high-tech manufacturing and R&D |

- Exemption from profit tax |

|

Advanced development zones (ADZ) |

In the Russian Far East and Eastern Siberia, there are plans to establish a network of advanced development zones with preferential conditions for non-resource production which is oriented to exports, among other things. ADZs offer special terms for companies operating in various industries (such as agriculture, textiles, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, furniture, telecommunications, education, science and technology), including income tax and property tax incentives, free customs zones, project financing, and simplified rules for hiring foreign employees.

|

Source: Fitch Solutions

- Value Added Tax: 20%

- Corporate Income Tax: 20%

Source: Federal Tax Service of Russia

Important Updates to Taxation Information

- Starting from January 1, 2019, the VAT rate increased from 18% (in 2018) to 20%.

- The maximum corporate income rate has been set at 20%. Over the next five years, the 20% tax will be allocated in such a manner that 3% goes to the federal budget and 17% is allocated to the budgets of the relevant constituent regions. The rate of tax payable to regional budgets can be reduced under regional law for certain categories of taxpayers, such that the reduced regional rates introduced before September 3, 2018 will apply until the date of their expiry and/or a final date of January 1, 2023.

- On January 1, 2019, new changes were introduced, which will require foreign entities to register for VAT purposes and pay the relevant taxes if they provide electronic services to legal entities and individual entrepreneurs.

Business Taxes

|

Type of Tax |

Tax Rate and Base |

|

CIT |

20% on profits (can be reduced by certain incentives depending on location) |

|

Withholding Tax Rates |

- 15% on dividends and income from participation in Russian enterprises with foreign investments |

|

VAT |

20% on sale of goods and services |

|

Property Tax |

Maximum rate of 2.2% on book value of property |

|

Mineral Resources Extraction Tax |

3.8%-8%, but generally variable according to the industry and the value and volume of the commercial resource |

Sources: Federal Tax Service of Russia

Date last reviewed: April 29, 2020

Localisation Requirements

Performance requirements, such as job creation or investment minimums, can be imposed as a condition for establishing, maintaining or expanding an investment. Securing a work permit in Russia is the employer's responsibility and the deadline for the foreign labour requirement falls on May 1 annually.

Migrant Labour Regulations

There are three types of work visas in Russia: first, the single-entry visa, which lasts for 90 days and is issued by the Russian consulate on the basis of a work visa invitation; second, the multiple-entry visa, which is reissued on the basis of a single entry at a local branch of the Russian Federal Migration Service; third, the Highly Qualified Specialists (HQSs) visa for specialists who earn more RUB2 million per year.

The cost and duration taken to acquire a working visa in Russia varies according to the country of an individual's origin. If permits are required, the complicated and time-consuming application process raises costs for employers and there is considerable risk for the employer as the information given in the application is binding.

The application requires details of the position they intend to fill, as well as the nationality of the expat. The process can take up to a year and once granted a permit is valid only for the specific job it was issued for and cannot be transferred to different companies or subsidiaries of companies in other regions in Russia.

If the employer requires the employee to work in different parts of the country, the application must be completed for every region the employee will work in.

Obtaining Foreign Worker Permits

Any foreign citizen who works in Russia must hold a work permit or patent, and the employer or purchaser of work (services) of such foreign citizen must hold a valid employer permit. Effective from January 2015, foreign nationals who apply for a work permit, patent, temporary residence permit or permanent residence permit are required to present a certificate confirming their knowledge of Russian language, history and basics of Russian law.

Overall, securing a working visa in Russia is both complex and relatively expensive, presenting bureaucratic and cost burdens to investors looking to import foreign labour. Russian immigration authorities operate a visa quota system for foreign workers. Immigration authorities have been given powers to revoke quota allocations to employers if they are found to be in breach of Russian labour and tax laws.

Obtaining Foreign Worker Permits for Skilled Workers

A beneficial immigration regime is available for highly qualified foreign nationals working in Russia who are employed by Russian companies or Russian branches and representative offices of foreign companies. These individuals are referred to as HQSs. To qualify for this permit, foreign specialists must be compensated with no less than RUB2 million per year. The permit can be issued for up to three years. The Russian language requirement does not apply to the processing of work permits and permanent residence permits for highly-qualified professionals.

Visa/Travel Restrictions

Visas are issued by diplomatic missions or consulates of Russia, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs or the Ministry of Internal Affairs (directly or by proxy). Visas can be single-entry, double-entry or multiple-entry. Ordinary visas are divided into private, business, tourist, study, work, humanitarian and entry visas for persons seeking asylum. Foreign citizens from most CIS countries and those who are permanent or temporary residents of Russia do not need entry visas.

Sources: Government websites, Fitch Solutions

Sovereign Credit Ratings

|

Rating (Outlook) |

Rating Date |

|

|

Moody's |

Baa3 (Stable) |

08/02/2019 |

|

Standard & Poor's |

BBB- (Stable) |

23/02/2018 |

|

Fitch Ratings |

BBB (Stable) |

07/02/2020 |

Sources: Moody's, Standard & Poor's, Fitch Ratings

Competitiveness and Efficiency Indicators

|

World Ranking |

|||

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

|

Ease of Doing Business Index |

35/190 |

31/190 |

28/190 |

|

Ease of Paying Taxes Index |

52/190 |

53/190 |

58/190 |

|

Logistics Performance Index |

75/160 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Corruption Perception Index |

138/180 |

137/180 |

N/A |

|

IMD World Competitiveness |

45/63 |

45/63 |

N/A |

Sources: World Bank, IMD, Transparency International

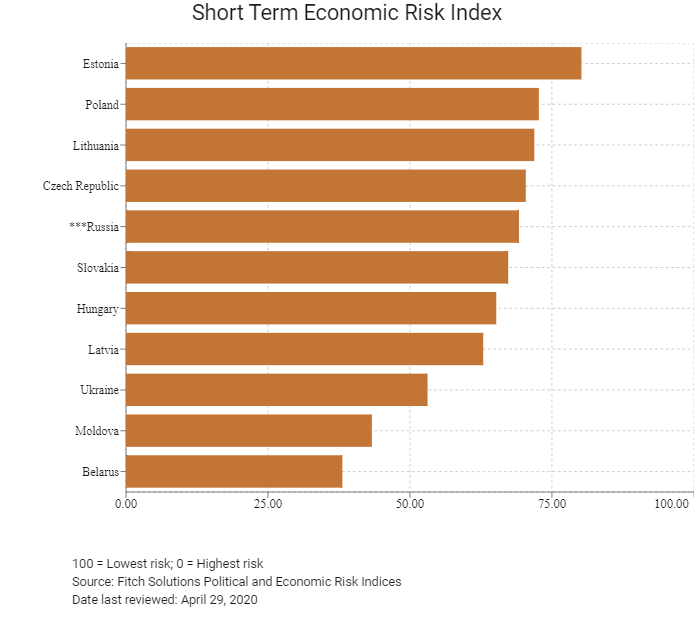

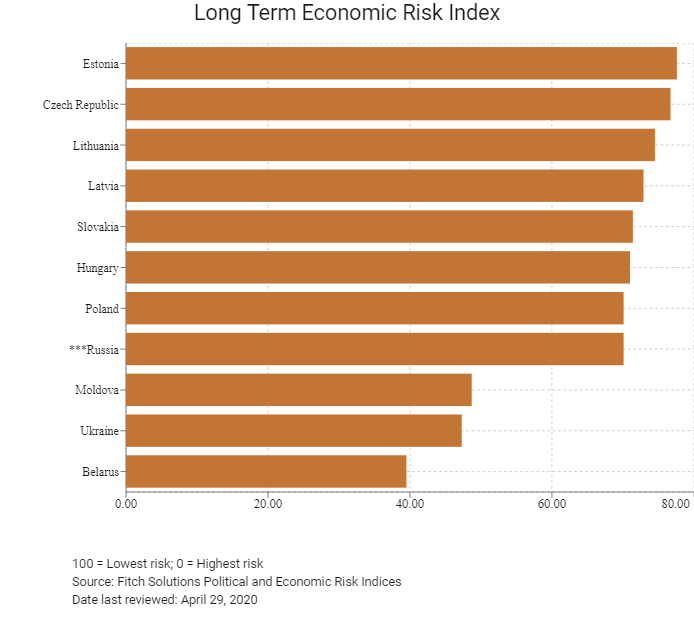

Fitch Solutions Risk Indices

|

World Ranking |

|||

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

|

Economic Risk Index Rank |

47/201 |

34/201 |

36/201 |

|

Short-Term Economic Risk Score |

68.3 |

67.5 |

69.2 |

|

Long-Term Economic Risk Score |

66.3 |

70.1 |

70.1 |

|

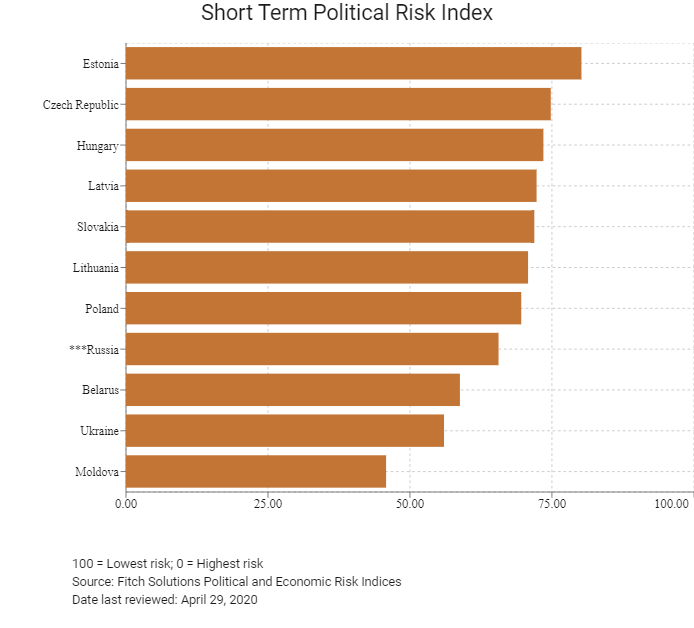

Political Risk Index Rank |

102/201 |

98/201 |

99/201 |

|

Short-Term Political Risk Score |

65.6 |

65.6 |

65.6 |

|

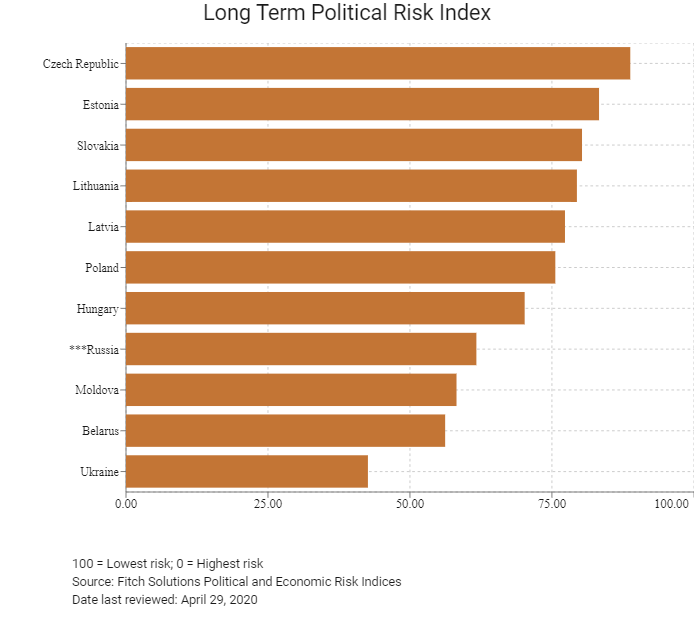

Long-Term Political Risk Score |

61.7 |

61.7 |

61.7 |

|

Operational Risk Index Rank |

68/201 |

63/201 |

63/201 |

|

Operational Risk Score |

55.9 |

57.7 |

58.0 |

Source: Fitch Solutions

Date last reviewed: April 29, 2020

Fitch Solutions Risk Summary

ECONOMIC RISK

Russia's economic performance compares relatively well against other emerging market peers due to low public debt ratios, high FX reserves and a current account surplus. The government is expected to embark on a much looser fiscal trajectory over the coming months to cushion the Covid-19-induced economic fallout. Hit by the coronavirus outbreak and collapsing commodity prices, the Russian economy will contract in 2020. However, after years of fiscal consolidation and deleveraging, the country is now better placed to avoid a financial crisis and usher in a stronger recovery, with growth likely to rebound in 2021.

OPERATIONAL RISK

While access to a large labour market, strong urban transport links, vast natural resources and a robust financial sector are key factors that are supportive of economic activity in Russia's long-term outlook, the market remains hamstrung by structural challenges that highlight the slow pace of reform over the years. Businesses operating in Russia face risks stemming from high levels of government intervention in the economy, an infrastructure deficit in some areas and an ageing population. However, the development of the Asia-Europe land bridge will strengthen Russia's international trade links while need to reduce the burden of state-owned enterprises has ensured that privatisation climbs up the agenda. Looking ahead, further delays to the government's infrastructure investment programme, uncertainty over US sanctions, volatile commodity prices and global trade tensions signal key near-term risks.

Source: Fitch Solutions

Date last reviewed: April 30, 2020

Fitch Solutions Political and Economic Risk Indices

Fitch Solutions Operational Risk Index

|

Operational Risk |

Labour Market Risk |

Trade and Investment Risk |

Logistics Risk |

Crime and Security Risk |

|

|

Russia Score |

58.0 |

65.9 |

57.4 |

67.9 |

40.6 |

|

Central and Eastern Europe Average |

62.5 |

58.6 |

62.8 |

67.5 |

61.2 |

|

Central and Eastern Europe Position (out of 11) |

9 |

1 |

9 |

7 |

10 |

|

Emerging Europe Average |

57.7 |

56.3 |

58.1 |

60.5 |

55.9 |

|

Emerging Europe Position (out of 31) |

19 |

2 |

21 |

9 |

26 |

|

Global Average |

49.6 |

50.2 |

49.5 |

49.3 |

49.2 |

|

Global Position (out of 201) |

63 |

20 |

72 |

43 |

133 |

100 = Lowest risk; 0 = Highest risk

Source: Fitch Solutions Operational Risk Index

|

Country/Region |

Operational Risk Index |

Labour Market Risk Index |

Trade and Investment Risk Index |

Logistics Risk Index |

Crime and Security Risk Index |

|

Estonia |

70.9 |

63.1 |

75.0 |

71.0 |

74.3 |

|

Czech Republic |

69.4 |

60.6 |

67.0 |

73.6 |

76.5 |

|

Lithuania |

69.4 |

61.3 |

71.1 |

74.3 |

71.0 |

|

Poland |

68.1 |

59.2 |

64.9 |

75.5 |

72.8 |

|

Latvia |

67.1 |

63.5 |

68.2 |

69.4 |

67.4 |

|

Slovakia |

63.7 |

52.1 |

66.2 |

66.8 |

69.6 |

|

Hungary |

63.6 |

55.7 |

62.5 |

70.1 |

66.3 |

|

Belarus |

59.2 |

60.1 |

58.7 |

66.6 |

51.3 |

|

Russia |

58.0 |

65.9 |

57.4 |

67.9 |

40.6 |

|

Moldova |

49.7 |

44.8 |

51.4 |

53.4 |

49.3 |

|

Ukraine |

48.6 |

57.9 |

48.4 |

54.4 |

33.6 |

|

Regional Averages |

62.5 |

58.6 |

62.8 |

67.5 |

61.2 |

|

Emerging Markets Averages |

46.9 |

48.5 |

47.2 |

45.8 |

46.0 |

|

Global Markets Averages |

49.6 |

50.2 |

49.5 |

49.3 |

49.2 |

100 = Lowest risk; 0 = highest risk

Source: Fitch Solutions Operational Risk Index

Date last reviewed: April 29, 2020

Hong Kong’s Trade with Russia

| Export Commodity | Commodity Detail | Value (US$ million) |

| Commodity 1 | Telecommunications and sound recording and reproducing apparatus and equipment | 1,931.0 |

| Commodity 2 | Office machines and automatic data processing machines | 522.8 |

| Commodity 3 | Electrical machinery, apparatus and appliances and electrical parts thereof | 392.2 |

| Commodity 4 | Professional, scientific and controlling instruments and apparatus | 245.8 |

| Commodity 5 | Miscellaneous manufactured articles | 109.9 |

| Import Commodity | Commodity Detail | Value (US$ million) |

| Commodity 1 | Non-ferrous metals | 350.4 |

| Commodity 2 | Non-metallic mineral manufactures, n.e.s. | 201.4 |

| Commodity 3 | Miscellaneous manufactured articles, n.e.s. | 148.4 |

| Commodity 4 | Coal, coke and briquettes | 95.1 |

| Commodity 5 | Power generating machinery and equipment | 47.3 |

Exchange Rate HK$/US$, average

7.75 (2015)

7.76 (2016)

7.79 (2017)

7.83 (2018)

7.77 (2019)

|

2019 |

Growth rate (%) |

|

|

Number of Russian residents visiting Hong Kong |

138,679 |

-14.4 |

|

Number of European residents visiting Hong Kong |

1,747,763 |

-10.9 |

Source: Hong Kong Tourism Board

|

2017 |

Growth rate (%) |

|

|

Number of Russians residing in Hong Kong |

114 |

29.5 |

Note: Growth rate for resident data is from 2015 to 2019, no UN data available for intermediate years

Source: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs – Population Division

Date last reviewed: May 5, 2020

Commercial Presence in Hong Kong

|

2019 |

Growth rate (%) |

|

|

Number of Russian companies in Hong Kong |

N/A |

N/A |

|

- Regional headquarters |

||

|

- Regional offices |

||

|

- Local offices |

Treaties and agreements between Hong Kong and Russia

- Alongside the Air Services Income Agreement effective since June 2010, Hong Kong signed a Comprehensive Double Taxation Agreement (CDTA) with Russia on January 18, 2016, which entered into force on July 29, 2016. To accommodate greater synergies, Hong Kong and Russia are also in the process of negotiating an Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement (IPPA).

- Mainland China and Russia signed an agreement for the Avoidance of Double Taxation (DTA) on October 13, 2016 and Investment Promotion and Protection Agreements which came into effect on February 12, 2000.

Sources: Hong Kong Inland Revenue Department, Fitch Solutions

Chamber of Commerce or Related Organisations

Russia-Hong Kong Business Association

Email: info@russiahk.ru / pa@raschini.com

Tel: (7) 495 740 8833

Website: www.russiahk.com

Please click to view more information.

Source: Federation of Hong Kong Business Associations Worldwide

Russian Consulate General in Hong Kong

Address: Rooms 2106-2123, 21/F, Sun Hung Kai Centre, 30 Harbour Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong

Email: cghongkong@ya.ru

Tel: (852) 2877 7188

Fax: (852) 2877 7166

Source: Consulate General of the Russian Federation in Hong Kong

Visa Requirements for Hong Kong Residents

No visa is required for up to 14 days for HKSAR passport holders. Before entering Russia the migration card must be filled in and presented to the migration officer when entering and exiting Russia. The card is also required for migration registration at the place of stay, and must be kept by the foreign national during their stay in Russia. A visa is required for stays longer than 14 days.

Source: Consulate General of the Russian Federation in Hong Kong

Date last reviewed: April 29, 2020

448 Views

448 Views Russia

Russia