Chinese Mainland

Professor Feng Xiaoyun from Guangzhou’s Jinan University envisages that Guangdong-Hong Kong cooperation is set to reach new heights during the 13th Five-Year Plan period (2016-2020). In particular, under the country’s “One Belt, One Road” initiative, the building of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Big Bay Area will bring about significant advances in Guangdong-Hong Kong cooperation. Hong Kong, as the only global city in the Greater Pearl River Delta (PRD) region, will perform the functions of leading the PRD to “go out” and raising the level of internationalisation of the regional economy, making the city cluster in the region the most vibrant and internationally competitive in the Asia Pacific.

Professor Feng Xiaoyun of the College of Economics, Jinan University, pointed out at an international forum held in May this year that Guangdong-Hong Kong cooperation is set to reach new heights during the 13th Five-Year Plan period. In order to better understand this view point, Pansy Yau, HKTDC’s deputy director of research, interviewed Professor Feng at the Guangzhou CUHK Kaifeng Hotel.

Guangdong-Hong Kong cooperation is set to make significant advances during the 13th Five-Year Plan period because according to the framework agreements on Guangdong-Hong Kong cooperation and Guangdong-Macau cooperation signed by Guangdong with Hong Kong and Macau respectively in 2010, the three places will join hands in building a world-class city cluster in the region by 2020. In view of this, in the next five years, i.e. during the 13th Five-Year Plan period, major breakthroughs can be expected in the mode and mechanism of cooperation between Guangdong and Hong Kong in the course of promoting integration of regional economy and in basically forming a world-class city cluster.

General speaking, city cluster has two definitions. One is spatial integration of a number of cities in a specific region. The other is functional integration of the cities in that region. Functional integration means that each city in the region would have its specific function(s) and the functions of all the cities will add together to create a complementary relationship. As such, a city cluster usually has clear division of functions with each city performing different economic functions, which will work together to form a competitive city cluster.

In the Outline of the Plan for the Reform and Development of the Pearl River Delta (2008-2020), clear division of functions has been set out for different cities in the PRD. This includes positioning Guangzhou as a modern services centre in the south China region; Shenzhen as a technological research and innovation centre; Foshan and Dongguan as international high-end manufacturing bases; Zhuhai, Zhongshan and Jiangmen as advanced manufacturing bases in the mainland; and Huizhou as a petrochemical base.

As for Hong Kong, its positioning is to serve as the engine propelling PRD cities to go international and develop into global cities. Within the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau city cluster, Hong Kong’s biggest comparative advantage is its global network. As a matter of fact, in every city cluster, there is a city whose function is to lead the whole cluster to integrate into the global network. And the city undertaking this function is positioned as a global city. Currently, among the 11 cities in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau city cluster (comprising nine PRD cities, Hong Kong and Macau), Hong Kong is the only global city. In other words, the leader function performed by Hong Kong fully demonstrates her comparative advantage.

Hong Kong takes the lead among PRD cities in international transportation as well as commercial services such as financial and legal services, accounting, and marketing on a global level. Innovative systems being implemented in the Guangdong Pilot Free Trade Zone (GDFTZ) and efforts to further promote liberalisation of trade in services between Guangdong and Hong Kong are bound to strengthen Hong Kong’s role in leading the whole city cluster to integrate with the global network, as well as building the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Big Bay Area into an important hub along the Maritime Silk Road.

In the document Vision and Action on Jointly Building the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road issued earlier by three State Council ministries and commissions, it was specifically mentioned that efforts will be made to give full play to the functions of the GDFTZ in strengthening cooperation with Hong Kong and Macau and creating the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Big Bay Area along the Maritime Silk Road, and that the big bay area will play a very significant role in the building of the Maritime Silk Road.

Note: The Guangdong provincial government announced the Implementation Plan of Guangdong Province for Participating in the Construction of “One Belt, One Road” on 3 June, putting forward that efforts will be made to build the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Big Bay Area into a first-class international financial and trade centre, technological and innovation centre, transportation and shipping centre, and cultural exchange centre on the Maritime Silk Road, and that action will be taken to build a logistics hub in the big bay area for trade between China and countries along the Maritime Silk Road.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Helen Sloan, Editor of The Bulletin, HKGCC

Major infrastructure projects along the routes of the historical Silk Road are at the heart of the Belt and Road Initiative. But beyond these plans to build highways, ports and telecoms networks, the initiative is creating opportunities in some less expected areas.

Being geographically a long way from the traditional Silk Road, Latin America, at first, did not have an obvious role to play in the Belt and Road.

This changed last year when the Mainland described the region as a “natural extension” of the Maritime Silk Road. With this green light, investment and trade is likely to increase.

As Le Xia, Chief Economist for Asia at BBVA, explained, economic cooperation is not new. Trade has boomed in the past decade, with Latin America exporting everything from oil and copper to soy beans to China.

“If we look at interdependency, it is not only that Latin America depends on China,” Xia said, “but also China to some degree depends on Latin America for commodities. So, this interconnectedness between China and Latin America has increased quite a lot in recent years.”

Policy change

The shift in policy is still likely to have an impact. Chinese government agencies have targets to meet related to the Belt and Road, so if they are looking for ways to boost their performance in areas like exports, they have an incentive to consider the region.

China’s foreign direct investment (FDI) into Latin America, however, has lagged – it is much smaller than Japan’s total investment, for example.

“In the past China didn’t have a lot of FDI,” Xia said. “But gradually, investment has been picking up.” He expects that, in the near term, investment in energy and infrastructure will grow, as well as in sectors including telecoms, transportation, logistics, IT, electricity, mining and aviation.

Central Government policy is already driving investment in certain industries. Chinese Premier Li Keqiang has proposed a “3 x 3” model for boosting China-Latin America collaboration focusing on logistics, power and information.

Many of the deals that have hit the headlines have been huge agreements involving China’s state-owned companies – for example, State Grid’s acquisition of Brazilian power group CPFL Energia and Shandong Gold’s purchase of a 50% share in Barrick Gold’s Veladero mine in Argentina, one of the biggest gold mines in the world. Other Chinese companies active in the region recently include HNA, Three Gorges and COFCO.

Smaller private firms may find more difficulties investing in Latin America, among other overseas markets, due to “some headwinds from the policy side,” Xia said, referring to the crackdown on capital outflow.

“There is some concern that small companies want to move their production outside of China for the purpose of moving money overseas. For the short or even medium term, in the next couple of years, these small enterprises will face a lot of pressure from Chinese government regulations.”

However, this does not mean an outright ban, and manufacturers with a legitimate reason to make investments will still be encouraged.

Hong Kong companies, meanwhile, may find an outlet for their skills in finance, legal and arbitration. Xia reports that this is happening already, as companies including Chinese SOEs use Hong Kong to finance their projects in Latin America.

“As a part of China, Hong Kong is still the most international business-oriented place so it’s easier for Hong Kong to play this super-connector role in the Belt and Road.”

Latin America, of course, is not a uniform market. Traditionally, some nations have had strong relations with the U.S while others leaned more towards Mainland China. But the presidency of Donald Trump and his promises of more restrictive trade policies means that a change in attitude is in the air.

“Now, it seems more and more countries in Latin America are starting to realize the importance of China,” Xia said.

Bearing this out, a BBVA study has revealed a shift in attitudes towards China in the region. “We do find that Latin America countries now show more enthusiasm for Chinese investment. This is a very good sign. We can see it lays a good foundation for bilateral relations.”

PC Yu, Chairman of the Chamber’s China Committee, has also seen the term ‘Belt and Road’ attract increasing attention in Latin America.

“Chinese enterprises have established more than 2,000 businesses in Latin America, and bilateral trade in the first 10 months of 2017 exceeded $210 billion,” he said. “The region is becoming an integral part of joint efforts in developing the Belt and Road Initiative, and the synergy between the initiative and the development blueprints of the Latin American countries will help open a new window of opportunity for growth.”

He added that as China boosts trade with Latin America, it is increasingly interested in developing a robust infrastructure network that can efficiently ship goods from producing centers to export hubs along South America’s Pacific coast. “Investment in infrastructure, and in the areas of agriculture, energy and natural resources, reflects the fact that China’s presence is quite important in South America.”

Yu also expects that the growing cooperation between the Mainland and Latin America will benefit Hong Kong. “Under the principle of ‘one country, two systems,’ Hong Kong will assume an important role in areas such as finance and investment, infrastructure and shipping, economic and trade cooperation and promotion, people-to-people ties, and project interfacing and dispute settlement.”

Challenges ahead

Tracy Wut, Partner at Baker McKenzie, noted some of the challenges that investors may face in the region.

“A lot of these countries may not have a very strong legal regime to protect your rights when there is a dispute,” she said at a recent Chamber seminar.

Getting things done can also take a long time, she added. In Mexico, for example, a merger is not legally effective until it is registered with the public register, which can take two months.

But sometimes, a problem can turn out to be not quite as bad as it initially seemed. Understanding the key issues and whether they actually impact your deal are particularly important, she said.

“We cannot emphasis enough the importance of due diligence – not just paper, but the need for face-to-face meetings and Q&A sessions.”

Political instability and corruption in the region may also be of concern to investors. But, as Wut pointed out, this volatility has also presented opportunities.

“The most recent wave of Chinese investment has been supercharged by a corruption investigation that has swept Brazil,” she explained.

Known as Operation Car Wash, the probe has uncovered a web of corruption linking top politicians, state-owned firms and private contractors. It has bankrupted several companies and forced others to divest assets.

“This last, and perhaps most important factor, is the driver of a lot of investment in recent years because, suddenly, everything is for sale, from ports and highways to airports and railways.”

Green Opportunities

Another way companies can find less obvious opportunities arising from the Belt and Road Initiative is to use their specific and world-class industry knowledge. And green technology is one area where Hong Kong companies have got experience and expertise.

Steve Wong, Managing Director of energy consultancy BillionGroup Technologies, noted that sustainability is a priority of many Belt and Road projects. This is a change from when the Mainland started to open up.

“China in the last 40 years has been successful in lifting people out of poverty,” Wong said. “But at the same time, it generated a lot of environmental problems.”

Lessons have been learned and the Belt and Road will not continue with this polluting model. “That is why we must talk about a green One Belt One Road – and about ecological economic development, not just economic development.”

This demand for green development is also creating opportunities for legal and financial professionals to provide a framework for these cross-border deals. Wong also pointed out that Hong Kong’s role as a hub means that local companies are well-placed to call on the necessary global talent.

An engineer by training, Wong set up BillionGroup in 1991 as a building consultancy, changing focus to the energy sector in 2000. Wong admitted that this switch was a little bit “too early,” but now the group has found a market for its specialized skills across the globe in countries including Vietnam, Indonesia, and Bangladesh.

BillionGroup focuses on energy, waste management and infrastructure – all of which are in strong demand in developing countries along the Belt and Road. The company’s success in winning contracts is an example of the opportunities for businesses with specific expertise.

For Hong Kong companies seeking to get involved in Belt and Road projects, Wong advised that they need to offer services “to the top level, to even above the international level. We have to strive for excellence.”

To successfully bid for these contracts, Wong said: “You have to be the number one leader in your niche market, not the second.”

This article was first published in the magazine The Bulletin March 2018 issue. Please click to read the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Stephan Barisitz, Foreign Research Division, Oesterreichische Nationalbank; and

Alice Radzyner, European Affairs and International Financial Organizations Division, Oesterreichische Nationalbank

China’s New Silk Road (NSR) initiative was officially launched in 2013. It aims at enhancing overall connectivity between China and Europe by both building new and modernizing existing – overland as well as maritime – infrastructures. The NSR runs through a number of Eurasian emerging markets with important growth potential. The Chinese authorities have entrusted the Silk Road Fund, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and other institutions with financially supporting NSR activities. Most drivers of the initiative are of an economic or a geopolitical nature. Given the generous financial means at Beijing’s disposal and Chinese firms’ accumulated expertise in infrastructure projects, many undertakings are currently well under way and promise to (eventually) bring about considerable changes in connectivity, commerce and economic dynamism. While most Chinese NSR investments go to large countries (e.g. Pakistan, Malaysia, Indonesia, Russia, Kazakhstan and Kenya), the strategically situated smaller countries (e.g. Djibouti, Sri Lanka, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Serbia and Montenegro) typically benefit the most (in relation to the size of their economies). Progress has been made in strengthening the maritime infrastructural trade links with the EU (e.g. through the modernization of deep-water ports) while the upgrading of the currently rather weak trans-Eurasian railroad and highway links (e.g. via Kazakhstan and Russia) is clearly improving overland transportation’s yet modest competitive position.

This study is the first of a set of twin studies on the New Silk Road (NSR). In part I, we provide a project-oriented overview of China’s initiative to establish a New Silk Road linking China and Europe via a number of Eurasian and Asian emerging markets with important growth potential. In part II, we focus on the NSR’s implications for Europe, or more precisely, Southeastern Europe (SEE), through which it connects to the heart of the continent. We feel that our brief discussion of concrete projects can provide valuable geoeconomic and geopolitical insights that help us understand the motives, goals and implications of this major endeavor. As far as we know, no other study has yet analyzed the NSR’s impact from a project-oriented perspective, i.e. based on essential details of salient NSR projects in various parts of Eurasia and Africa. This contribution is intended to facilitate grasping the overall (potential) connectivity impact of the (strived-for) substantial modernization of trading networks.

Part I is structured as follows: Section 1 describes the most important features of the NSR, which is officially called the “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR) initiative, and the respective Chinese or multilateral financing institutions. Some motivations and reasons, but also risks and limitations, of the Chinese initiative are subject of section 2. Section 3 provides a snapshot of the approximate locations of the “economic corridors” of the NSR and a succinct discussion of the economic advantages and drawbacks of competing modes of transport, with important implications for OBOR projects. It also analyzes some major OBOR projects. Section 4 finally summarizes and draws some conclusions which help prepare the ground for part II …..

2. The New Silk Road: some motivations and reasons, challenges and risks

China’s OBOR initiative has been motivated and driven by a number of quite heterogeneous aims, which primarily include economic, but also geopolitical and even ecological issues:

• Improvement of transportation links, reduction of trade costs to Europe and other parts of Eurasia

The basic idea of the OBOR initiative is to better link up the “vibrant East Asian economic circle at one end and the developed European economic circle at the other”, following the example of the NSR’s predecessor, the traditional Silk Road, which lasted for about two millennia, witnessed many ups and downs, and linked the same two major traditional hubs of economic activity: the Middle Kingdom and Europe, or the Orient and the Occident. As, once again today, the world’s biggest trading nation, modern China’s interest is to reduce the costs of transporting goods (by land and sea) to other destinations. More efficient and secure and, if possible, shorter trade routes to Europe can further this goal.

The fact that about three-quarters of Chinese imports from Russia and 60% of Chinese imports from Kazakhstan are reportedly carried out via the ports of St. Petersburg and Vladivostok, although both Russia and Kazakhstan are immediate neighbors of China and share more than 2000 km of common borders with China, points to the relatively modest level of logistical development of intra-Eurasian overland trade. This may indicate vast connective potential for infrastructural projects in this area.

• Redirection of Chinese surplus savings, reutilization of domestic productive capacities and technical expertise for NSR investments

The NSR initiative can serve as a means of countering the recent marked downturn or weakened growth of the Chinese economy. The country probably has more savings than it can profitably invest at home. After many domestic infrastructure projects have been finished, Chinese infrastructure-related industrial and service sectors are saddled with overcapacities. OBOR’s economic dimension includes generating substantial foreign demand for reutilizing these domestic resources. This also relates to Chinese high-speed rail expertise: Chinese enterprises have gained great experience in high-speed rail construction within the country and are looking to apply their expertise in projects abroad now. While such aims are quite understandable, they would also appear to constitute an extension or resuscitation of China’s traditional economic model of export-led growth or at least a slowdown or interruption of its intended transition to domestic consumption-led economic expansion.

• Diversification of investments, markets and suppliers

One particular aim of the OBOR initiative is to hedge substantial existing Chinese placements in U.S. financial assets by investing in Eurasia. The NSR also promises to help diversify markets and suppliers through stimulating trade with landlocked or (so far) more difficult-to-access neighbors not yet trading that much with China. Infrastructure development in countries along the OBOR routes may raise growth in their economies and thus contribute to increasing demand for China’s goods and services.

• Creation of “strategic propellers of hinterland development”

This OBOR objective with respect to China’s less-developed central and western provinces has been put forward by Premier Li Keqiang. While Chinese growth has in recent decades favored the country’s eastern and coastal provinces, the NSR is to transform the northwestern province of Xinjiang into China’s infrastructural gateway to Central and Western Asia, which will open up opportunities for investment and stepped-up economic activity in this remote, politically somewhat restive, province. Correspondingly, in the southwest, the province of Yunnan should become the modernized “open door” to South Asia and the Indian Ocean. Thus, the authorities hope to tackle the socioeconomic divide (gross income inequalities) between economically peripheral inland and “connected” coastal provinces. Since all OBOR corridors depart from central or western provinces, the intended geoeconomic rebalancing could mitigate these disparities.

• Contribution to the internationalization of the Chinese renminbi-yuan

Alongside the development of closer trade and investment relations and deeper financial integration among OBOR countries, the Chinese authorities will promote the use of the renminbi-yuan in international transactions. The aim is to expand the scope and scale of bilateral currency swaps and settlements with other countries along the NSR. Efforts of governments of partner countries and their companies and financial institutions with good credit ratings to issue renminbi yuan-denominated bonds in China will be encouraged.

• Hedge in case of possible trade war

Since U.S. President Trump withdrew the U.S.A. from the Transpacific Partnership (TPP) in late January 2017, the TPP has lost much of its importance. Prospects for the conclusion of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) have also diminished considerably. Thus, the OBOR appears to be less under pressure than in the past to counterbalance potential rival trade initiatives. However, if a trade war between China and the U.S.A. were to break out, Beijing may expect enhanced connectivity and cooperation with NSR countries, notably with European partners, to soften the impact somewhat.

• Pragmatic infrastructural project cooperation as a possible way forward where trade integration areas have lost popularity

Pragmatic cooperation between one or more states and enterprises focusing on a particular infrastructural project (like a pipeline, a rail or highway link, a hydropower dam or electricity grid, a deep-sea port, etc.) provides task-oriented experience and may improve connectivity and intergovernmental relations. In a time of growing skepticism about trade and economic integration treaties such concrete, if limited, advances may promise greater success than traditional “deepening” efforts. At the same time, physical and nonphysical trade facilitation measures (the latter include the harmonization of customs, import, export and border crossing procedures) can arguably only be seen as complementary measures and not as alternatives.

• Venue for addressing strategic energy and resource security issues

Approximately 75% of China’s oil imports and an even higher share of its total imports are seaborne and pass through the Strait of Malacca between the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea (Escobar, 2015, p. 7; Grieger, 2016, p. 8). This geopolitical bottleneck could be closed by a military adversary in the case of conflict, which makes China potentially strategically vulnerable. China’s energy security is also put at risk by piracy that is rife in and near the area. China’s dependence on shipments through the Strait of Malacca has already been partly reduced by the creation of alternate (overland) trade channels, including the construction of pipelines from Central Asia10 and of corridors linking China directly to the Indian Ocean (via Pakistan and via Myanmar, see subsections 3.1 and 3.2).

• Ecological goal: reduction of China’s heavy reliance on polluting coal

China’s reliance on coal for about 40% of its heating and electricity has substantially contributed to pollution in its cities. The authorities have set ambitious goals for dealing with the pollution problem, including switching from coal to cleaner – but so far mostly imported – energy sources, e.g. natural gas from Central Asia and Russia.

Needless to say, the OBOR initiative also faces a number of challenges and risks:

• Weak local governance, sprawling bureaucracy and potential political instability

OBOR partner countries feature quite diverse political and economic conditions, with inherent risks ranging from possible legal and financial challenges to political or social instability and regional disparities. Given that many partner countries are not members of a political or economic integration area, border constraints (including possibly cumbersome clearance procedures and long waiting periods) may have to be coped with. The implementation of large infrastructure projects in the absence of well-performing and accountable government procurement systems may even add to local corruption and/or governance challenges.

• Frequent Chinese dominance in projects and possibly limited regard for local conditions may give rise to concern

While the preeminent position that Chinese project partners often assume in OBOR projects as regards finance, management and the deployment of Chinese firms and their workers may help speeding up a project, it may not favor broad positive spillover effects for local economies. In some cases, there may be the risk that insensitive behavior of investors (e.g. as regards labor, health and safety standards, quality of inputs used, respect for traditional local communities and the environment) gives rise to irritation and even protests on the part of the local population.

• Possible fallout from heightened geopolitical tensions or rivalry

A totally different risk is the possible negative (political) fallout from military tensions, e.g. in the South China Sea, which cannot be entirely discarded, either. Another risk is that projects may fall victim to a flare-up of geopolitical competition with other powers …..

4. Summary and conclusions

China’s New Silk Road (NSR) or One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative was officially launched in 2013. It focuses on linking China and Europe through increased connectivity and building or modernizing infrastructural trajectories, which include rail, road, port, airport, pipeline, energy and communication infrastructure and logistics. OBOR consists of an overland and a maritime branch. The overland Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) comprises various economic corridors which aim to bring China, Central Asia, Russia and Europe closer together (e.g. the New Eurasian Land Bridge) as well as to connect China to the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea through Central Asia and West Asia (e.g. the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor) or to strengthen links with Southeast and South Asia. The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (MSR) is designed to go from China’s coast to Europe through the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean, linking up en route with Southeast Asia, South Asia, East Africa and the Mediterranean.

The Chinese authorities have entrusted specific institutions with supporting NSR schemes: the Silk Road Fund (SRF, capital: ca. USD 55 billion), the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the New Development Bank (established by the BRICS member states), the China EXIM Bank, the China Development Bank and the Agricultural Development Bank of China.

The motivations and drivers of China’s OBOR initiative are mostly of an economic or geopolitical nature: improvement of transport links; reduction of trade costs; reutilization of domestic overcapacities; diversification of investments, markets and suppliers; development of peripheral domestic regions (e.g. Xinjiang); contribution to the internationalization of the renminbi-yuan; enhancement of security of access to strategic energy and resource supplies; hedging against possible trade wars, etc.

Challenges and risks include weak local governance and possible political instability in host countries. Given that maritime container transportation is substantially cheaper over long distances than transcontinental rail or road conveyance, the lion’s share of long distance trade over the NSR is likely to remain seaborne. However, apart from the fact that overland transportation is faster, the modernization of overland links, which are relatively weakly developed across Eurasia, is bound to reduce the price difference somewhat. A profitable niche for long-haul rail conveyance of high value-added and/or time-sensitive products seems to have emerged (including the Trans-Eurasia-Express, running from Chongqing via Astana and Moscow to Duisburg). Moreover, China’s trade with its immediate Eurasian neighbors (where there is little or no maritime competition) should clearly benefit from such efforts.

As of end-2016, all NSR projects actually in development are estimated to represent a total value of about USD 290 billion. Overall, while considerable resources have been devoted to MSR development, investments in SREB rail and road connections, against the backdrop of the huge modernization potential in this latter area, are now somewhat improving the competitiveness of Eurasian overland links. Thanks to the generous financial means at Beijing’s disposal (funds of at least USD 130 billion, not including funds from multilateral institutions) and the considerable experience Chinese firms have already accumulated in realizing domestic infrastructure projects, many OBOR investments are currently in full swing.

The lion’s share of Chinese NSR investments currently goes to Pakistan, Bangladesh, Malaysia, Indonesia, Russia, Kazakhstan and Kenya. However, compared to the size of respective host economies, strategically situated smaller countries typically benefit the most: Djibouti, Sri Lanka, Mongolia, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Cambodia, Serbia and Montenegro. The NSR promises to (eventually) bring about palpable changes as regards connectivity, commerce and economic dynamism in some important parts of Eurasia (including Southeastern Europe), which will be better linked up with – and more interdependent with – China once the NSR projects have been implemented.

This article was first published in Focus on European Economic Integration, issue Q3/17. Please click to read the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

As China’s connecting hub between the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Yangtze Economic Belt, as well as the strategic stronghold for the Western Region Development, Chongqing has been striving to build up a logistics network in its surrounding areas. This will open up a trade gateway to countries in Continental Europe and the surrounding region for the benefit of China’s inland cities, particularly those in the western region. To this end, the Chongqing-Xinjiang-Europe International Railway (also known as Yuxinou) serves as a pioneer in the opening up of trade routes on the northwest front of Chongqing.

In recent years, Chongqing has been taking forward the China-Singapore (Chongqing) Demonstration Initiative on Strategic Connectivity (or Chongqing Connectivity Initiative) co-operation framework by actively developing a southward trade route and logistics passage. In pursuance of its role as the logistics and transport hub for the western region, the Yuxinou railway and the southern transport corridor connect in Chongqing. Chongqing is making efforts to develop a multi-modal freight transport system integrating rail, air, sea and road with the Yuxinou railway as the pivot. Through the Yuxinou railway and the southern transport corridor, the Silk Road Economic Belt will link with the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road.

Chongqing Initiative Facilitates Southern Transport Corridor

The development of the Yuxinou railway is intended to open up the northwest trade route for Chongqing and build up China’s rail transport for trade exchanges with Europe and countries alongside. From the number of train runs, their running time, the geographical coverage as well as the cargo mix, it can be seen that the Yuxinou railway has already come a long way. Yet to shape Chongqing as a western region logistics hub, it cannot rely solely on the development of a single trade passage. In recent years, therefore, Chongqing has actively engaged in the development of a southward trade passage under the framework of the Chongqing Connectivity Initiative.

Concluded and commenced in 2015, the Chongqing Connectivity Initiative was the third co-operation project between China and Singapore. One of its focuses is to develop transportation logistics, with the aim of transforming Chongqing into a comprehensive connectivity transport hub for China’s western region through the promotion of a multi-modal freight transport system that integrates rail, air, sea and road transit modes.

The Chongqing Connectivity Initiative aims at opening up the southward trade logistics passage from Chongqing to Singapore and other Southeast Asian countries. It uses the logistics network of a southward rail-sea intermodal passage (the Chongqing-Guizhou-Guangxi-Singapore Rail-sea Intermodal Passage) and the southward cross-border road passage via the provinces of Sichuan, Guizhou and Guangxi.

The southward rail-sea intermodal passage is formed by the international rail-sea intermodal railway and the southward passage sea route, where the rail-sea intermodal railway connects Chongqing Rail Port and Beibu Gulf Port in Guangxi over a distance of some 1,450 km and a travel time of 48 hours. It came into regular two-way operation in 2017 and connects the sea-based transportation network at Beibu Gulf Port, where cargoes are exported to Southeast Asia, Australia and New Zealand by sea. According to the Modern Logistics Office of the Chongqing Commerce Commission, a total of 48 train runs were made from Chongqing to Guangxi via Guizhou in 2017.

Apart from the rail-sea intermodal railway, Chongqing has also strengthened its cross-border transportation service along its southbound highway. In particular, the Chongqing-ASEAN Regular Lorry began operating in April 2016 in order to provide a highway freight service between Chongqing and ASEAN. The lorry transport service has five ‘fixed’ features, namely a fixed starting point at the Chongqing-ASEAN International Logistics Park, fixed shuttle routes, fixed vehicles (standard container trucks), fixed weekly timetables and fixed transportation fees. Customised and specialised services are also available upon request.

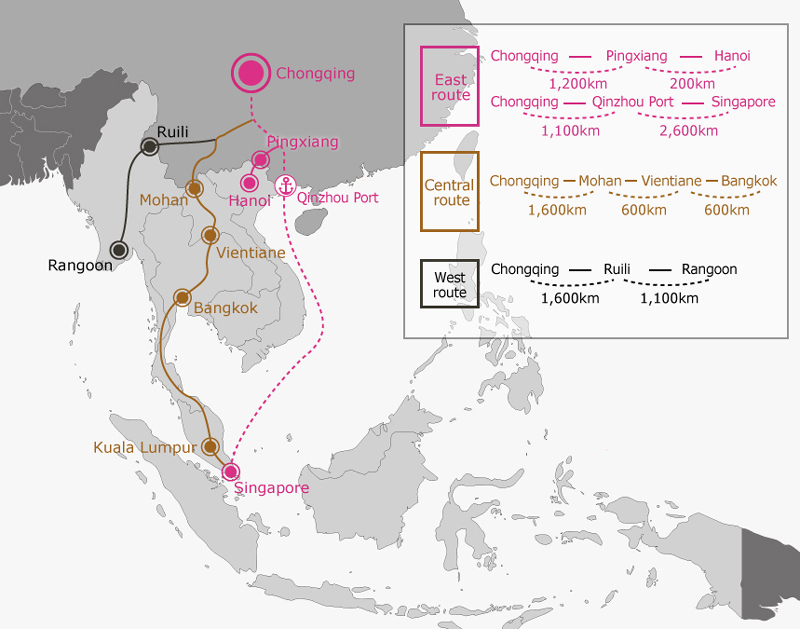

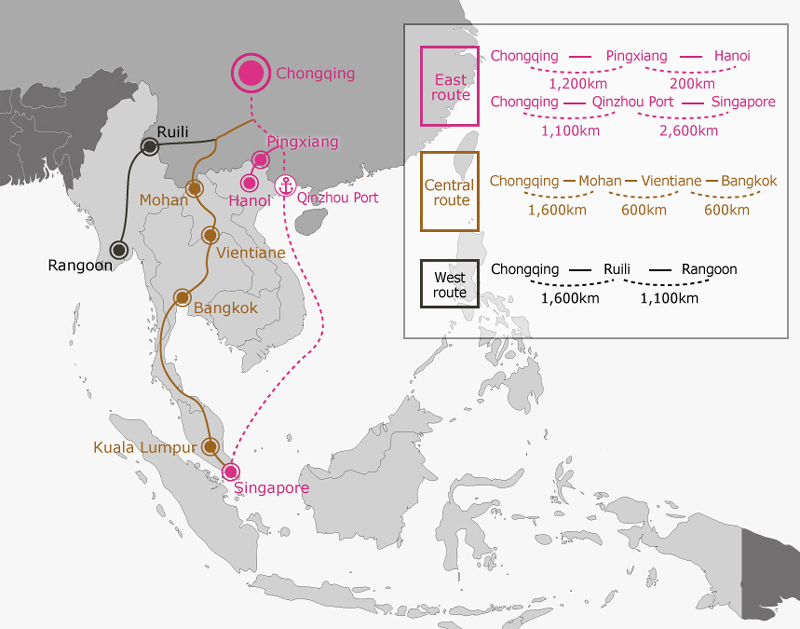

Planned Route Map of Chongqing-ASEAN Highway Shuttle

The three main planned shuttle routes include the east route running from Nanpeng in Chongqing to Hanoi in Vietnam via Pingxiang in Guangxi, together with a secondary east route to Singapore via sea transit at Qinzhou Port; the central route to Bangkok in Thailand via Mohan in Yunnan and Vientiane in Laos; and the west route to Rangoon in Myanmar via Ruili in Yunnan.

According to Chongqing-ASEAN International Logistics Park, the Chongqing-ASEAN Regular Lorry service has not yet come into full operation. In particular, the west route is not yet open and the central route is only operating on a partial basis. Due to the lack of an optimal transport network, the central route presently only reaches Vientiane in Laos, where the lorry has to switch to the east route to complete the journey to Bangkok. As for the secondary east route, its planned Vietnam destination has been extended from Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City in the south, allowing the route to cover nearly 80% of Vietnam.

From the commencement of operations to the end of 2017, the Chongqing-ASEAN Regular Lorry have made a total of 137 trips. In 2017 alone, 100 trips were reportedly completed, involving a total freight load of 1,027 tons and an aggregate cargo value of some RMB167 million. The goods in transit comprised building materials, glass products, auto parts and clothing, and mainly came from Chongqing, Sichuan, Gansu, Shanxi and Europe.

Time-saving Passage Connecting North and South

While the Yuxinou railway and southern transport corridor should help reinforce the logistics function of Chongqing, the city’s role as a comprehensive western region transport hub relies more on the connectivity of different logistics formats. At present, Chongqing is striving to develop a multi-modal transport system to provide a trade route that runs from the south to the north, linking up the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road.

Located at the upper reaches of the Yangtze River, Chongqing serves as a connecting point between the BRI and the Yangtze Economic Belt. One element of its multi-modal freight transport system is the sea-rail intermodal transportation that links the Yuxinou railway and the ‘golden waterway’ of the Yangtze. Since the launch of the Yuxinou railway in 2011, its only start point has been located at Chongqing Western Logistics Park in Shapingba district. Its second start point came into being at the end of 2017 with the official opening of the Chongqing Guoyuan Port Rail Line. Since then, all cargo transported to Guoyuan Port via Yangtze no longer need to make a highway trip to connect to the Yuxinou railway at the Western Logistics Park. This signifies the seamless connection between the Yangtze golden waterway and the Yuxinou railway, which has helped to further reduce logistics and transportation costs as well as the time involved.

The operation of the southern transport corridor also leads to the formation of the rail-sea intermodal transportation and logistics system. Traditionally, goods exported from Chongqing to major ports around the world by sea need to be shipped to eastern China via the Yangtze River first before they can depart from China, with this involving the use of river-sea intermodal transportation. However, the southern transport corridor brings a more efficient form of rail-sea intermodal transportation. For the river-sea transportation from Chongqing to coastal cities on the east via the Yangtze, it involves a distance of 2,400 km and typically takes more than 14 days to complete, whereas the rail trip to Beibu Gulf in the south only takes about two days, covering a distance of 1,450 km.

In terms of geographical location, Beibu Gulf at the Yangtze estuary is closer than Shanghai to other Southeast Asian countries. For example, a trip from Chongqing to Singapore by rail and sea will take 15 days less than by river and sea. Although the shipping cost involved in rail-sea intermodal transportation is similar to that of the river-sea format, it can significantly save on the transportation time from Chongqing to the major ports in the ASEAN bloc, thus reducing the time cost involved.

While the southern transport corridor has a shorter history than the Yangtze channel, its operation has undoubtedly opened up additional opportunities for the Yuxinou railway through its link in Chongqing, which only strengthens its BRI connectivity.

Taking the cross-border transportation service of the southbound highway as an example, the Chongqing-ASEAN Regular Lorry service has linked up with the Yuxinou railway on a regular basis since mid-2017. Through the rail-sea intermodal transport system, a trip along the southern transport corridor connecting the Yuxinou railway from Beibu Gulf port to Europe via Chongqing will take a total of 20 days only.

In the future, the multi-modal freight transport system, with the Yuxinou railway as the pivot, will be further optimised and extended. With Chongqing as its hub, the system can reach as far as the European continent to the north and all parts of the world by sea to the south.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By KPMG

We are living in exciting times for Southern China. Nowhere is this seen more clearly than in the ambitious plans being drawn up for the Greater Bay Area initiative, and its goal of building a world-class city cluster across the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau region. By 2030, the region is expected to play a leading role in advanced manufacturing, innovation, shipping, trade and finance.

The proposed initiative is a testament to the region’s economic development and significance. Last year, the combined GDP of the 11 cities in the area reached US$1.4 trillion, or 12 percent of the national economy, even though it is home to only 5 percent of the country’s population.

As the area develops, its influence is likely to extend beyond the geographical boundaries of its city cluster to play a key role in China’s Belt and Road Initiative, serving as a key link connecting countries along the 21st century Maritime Silk Road.

The purpose of this report is twofold: to highlight the key issues confronting the Greater Bay Area’s development, and to offer a market view of the Greater Bay Area. This was gathered from a survey of 614 business executives at companies operating in the region that was jointly devised and conducted by KPMG, the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce (HKGCC) and YouGov.

In addition to the survey, KPMG and HKGCC conducted several interviews with companies operating in the region for their viewpoints. The interviewees are from diverse backgrounds, including both state-owned and privately-owned enterprises, as well as small and medium-sized companies.

We would like to express our gratitude to all our survey respondents for their input, and to the executives who kindly agreed to be interviewed for this report. We hope that our findings will prove useful to understanding the challenges and opportunities facing the Greater Bay Area and its development in the coming years.

Executive Summary

Businesses overwhelmingly support China’s Greater Bay Area initiative, according to a YouGov survey commissioned jointly by KPMG and the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce. The two-month survey was conducted in June and July 2017 and received responses from 614 business executives in Hong Kong (410), Guangzhou (91), Shenzhen (82) and other GBA cities (31). Of the total respondents, close to 65 percent were at a senior management level, while around 35 percent were middle management or below. The companies they represent were from a wide range of industries, including manufacturing (157), distribution (143), e-commerce (73), retail (70), logistics (58), and others. The idea of Hong Kong, Macau and Guangdong working together to create GBA resonated with the survey respondents with 80 percent indicating their support for integrated development across the region.

The strongest backers were those working in Shenzhen, with 85 percent of those polled supporting the project, followed by Macau (83 percent), Hong Kong (80 percent) and Guangzhou (78 percent).

In addition, the respondents highlighted improved corporate synergies, a freer flow of talent and enhanced abilities to penetrate markets as the leading benefits to arise from the initiative. Many respondents (37 percent) believed the GBA will be able to rival the Greater Tokyo Metropolitan Area in terms of economic scale in a decade’s time. Fewer see it rivalling San Francisco Bay (32 percent) or Greater New York (28 percent).

Hong Kong respondents are the most optimistic about the GBA’s competitiveness. More respondents with Hong Kong-based operations – 41 percent of those surveyed – believed that the GBA would be on par with the Greater Tokyo Area in a decade’s time compared to those with operations based in mainland China – 34 percent of the total.

The sectors seen as most likely to benefit from the area’s development are trade and logistics (68 percent), financial services (62 percent) and R&D in innovative technologies (60 percent).

There are, however, challenges to be overcome in order for the GBA to fulfil its ambitions. Those surveyed identified protectionism and other measures that hinder cooperation as the biggest hurdle to the area’s development, followed closely by silos between and within GBA governments.

On the other hand, companies also see government support as the most important factor for the region’s success, followed by the rule of law and infrastructural support. As a result, how governments choose to participate and be involved will be crucial in determining the future of the Greater Bay Area.

Greater Bay Area Overview

The Greater Bay Area (GBA) initiative’s goal is ambitious: combining Hong Kong, Macau and the cities of Guangdong’s Pearl River Delta to create a region with the economic heft that is comparable to the San Francisco Bay Area, Greater New York and the Greater Tokyo Area. To succeed, the relevant infrastructure, policies and regulations will all have to be in place to ensure people, goods and services are able to flow freely within the region.

China’s transformation from an agricultural economy into a manufacturing powerhouse over the past few decades has been nothing short of phenomenal. The country is in the midst of another major shift towards a service driven economy and nowhere is this truer than in the Pearl River Delta, where Shenzhen, for example, is one of the world’s leading high-tech innovation centres.

The region is also at the heart of a network of supply chains that link Guangdong to the rest of the world and is able to draw on a strong manufacturing base. Last but not least, the region is also supported by Hong Kong’s world-class financial and professional services industries.

The further growth of the region, however, calls for greater coordination of financial, material and human resources – hence China’s decision to push for the establishment of GBA.

This landmark initiative aims to bring together the key cities of the Delta region to build a new powerhouse – one that is comparable to other city clusters such as Greater Tokyo Area, San Francisco Bay Area and Greater New York.

The right numbers

The GBA’s eleven cities have a total population of nearly 67 million, which is greater than the Tokyo Metropolitan Area - the world’s largest city cluster with a population of 44 million. The GBA also has a combined GDP of US$1.34 trillion, which is lower than the US$1.61 trillion of Greater New York and US$1.78 trillion of Greater Tokyo.

Hong Kong remains the single biggest economy of the area, but only just. Its GDP, at US$319 billion in 2016, is likely to be overtaken by Guangzhou (US$285 billion) and Shenzhen (US$283 billion) in the foreseeable future.

High-level backing

The concept of GBA dates back to 2011 with a study called “The Action Plan for the Bay Area of the Pearl River Estuary” that was jointly prepared by officials from Hong Kong, Macau, Shenzhen, Dongguan, Guangzhou, Zhuhai and Zhongshan. The idea of a city cluster in Southern China was reinforced when the 13th Five Year Plan (2016-2020) was endorsed in March 2016. Premier Li Keqiang subsequently announced in the annual government report in March 2017 that the authorities were going ahead with the initiative.

This led to a framework agreement in July 2017, which was signed by China’s top policy-making body, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and the governments of Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macau.

One of the GBA’s key objectives is to improve the level of cooperation within the region. This includes identifying the core competitive advantages of the cities within GBA and exploring ways for them to complement one another. One example of this is to build on the strengths of Hong Kong’s financial and professional services sectors, Shenzhen’s high-tech manufacturing and innovation skills, and the manufacturing strengths of Dongguan and Guangzhou.

Within China, the GBA has the potential to extend its reach beyond the Pearl River Delta to the nearby provinces of Fujian, Jiangxi, Hunan, Guangxi, Hainan, Guizhou and Yunnan. Beyond China, it will be aiming to reach markets in Southeast and South Asia.

The development of the area should also act as a catalyst for China’s Belt and Road Initiative - an ambitious strategy that aims to link the economies along the Silk Road Economic Belt (Central Asia to Europe) and the Maritime Silk Road (South Asia to Africa and the Middle East) together.

The cities of the area offer a wide range of skills and services, and they should develop according to their comparative advantages. One possible approach would be for R&D to be conducted in Shenzhen, Hong Kong or Guangzhou and manufacturing to be carried out in Dongguan and other cities across the Delta.

Companies can take advantage of Hong Kong’s “one country, two systems”, which makes it a part of China but with its own legal and financial regimes. They can also tap into Hong Kong’s status as the gateway between China and the world and as an international financial centre for fundraising, asset and risk management, corporate treasury services, insurance and re-insurance and, more recently, offshore renminbi services.

In addition, the region already possesses some of the most efficient supply chains in the world as well as a well-developed talent pool fluent in English and Chinese.

Next steps

Enhanced cross-border movements of capital, people, goods and services within the GBA are essential for the region’s successful development. As cities in the GBA fall under different customs zones as well as legal and administrative systems, improvements in cross-border movements are highly dependent on cross-institutional cooperation and efforts.

The most pressing issue is for local governments within the region to collaborate on a broad range of topics. This includes economic policies, environmental and transport issues, and regulatory harmonisation.

There is evidence that officials are looking for ways of making progress in all these areas. One example is the Guangdong free-trade zone, which was launched in 2015 across 60 square kilometres of the Nansha New Area in Guangzhou, 28 square kilometres of the Qianhai and Shekou areas in Shenzhen and 28 square kilometres of Hengqin in Zhuhai.

This was followed by the proposed development of the Lok Ma Chau Loop when Hong Kong and Shenzhen signed an agreement in January 2017 to transform a stretch of land on the border between the two cities into an innovation and technology park.

Moreover, the completion of the Zhuhai-Hong Kong Macao Bridge and the Express Rail Link will improve land connectivity and induce more cooperation among GBA cities. These projects, in combination with many other initiatives, will make the GBA a key contributor to the further opening up of the Chinese economy.

Looking Ahead

The development of the GBA is a key priority for Hong Kong. To take full advantage of the opportunities this initiative presents, Hong Kong must focus on three key areas. First, the sectors with the biggest competitive advantages: international finance, shipping and logistics, offshore renminbi transactions and dispute resolution. Second, the unique features offered by the “one country, two systems”, notably Hong Kong’s adherence to the rule of law. Thirdly, the city’s strength in combining its proximity to the GBA’s manufacturing base with its connectivity to the rest of the world.

The key to developing the GBA will be finding ways of cooperation that unify and optimise the region’s city economies. With the cities of the GBA falling under different customs zones and legal and administrative systems, improvements in cross-border movements will depend very much on efforts to strengthen institutional cooperation and collaboration across the region. Success, however, will allow the region to move towards enhanced – preferably seamless – cross-border movements of capital, people, goods and services.

Over the past few decades, the GBA cities have each developed their own unique advantages, economic structures and needs. To help companies become more aware of these, the Hong Kong government should set up a GBA Office to formulate proposals, strategies and policy directions. The GBA Office will be responsible for defining Hong Kong’s potential participatory role in the area’s development and economic growth, coordinating with relevant governments in the region, and disseminating official GBA information to the public.

Hong Kong should develop an overall development strategy with the goal of drawing up a comprehensive region-wide plan aimed at strengthening cooperation with Shenzhen and other cities across the GBA.

To strengthen capital flows within and beyond the GBA, Hong Kong should utilise its established financial infrastructure to facilitate RMB internationalisation, expand the various cross-border share and bond trading schemes to include a “Commodity-Connect”, and bolster its status as the region’s asset management centre.

The government should use the Lok Ma Chau Loop to test a range of pilot schemes, such as providing special work visas for GBA residents and ensuring that research funding sourced from Hong Kong and the mainland can be used by research institutes established there.

With the completion of the Zhuhai-Hong Kong-Macao Bridge and the Express Rail Link in sight, ways to improve the cooperation between the region’s airports for both passengers and cargo should be explored. GBA cooperation can also help Hong Kong achieve breakthroughs in areas where the city has encountered bottlenecks in recent years. This includes waste management, housing, education and opportunities for young people, and elderly care.

As Asia’s most dynamic economic region, the GBA will be an important growth engine for mainland China in the coming years.

Success, however, will depend on mutual collaboration and cooperation.

Please click to read the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Over recent years, China has actively expanded its rail freight transport links with Europe, as well as with individual countries along the routes of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). As of early 2018, the China-Europe Railway Express (CR Express) operated 61 routes in 43 mainland cities with connections to 41 cities in 13 European countries.

Located strategically in China’s central-western region, Chongqing enjoys direct links to the prosperous Yangtze Economic Belt. It is also the starting point for the Chongqing-Xinjiang-Europe International Railway, which has played a pioneering role in opening up China-Europe rail trade. The railway is also known as Yuxinou, a name derived from a combination of its Chinese characters – Yu (which stands for Chongqing), Xin (Xinjiang) and Ou (Europe).

Yuxinou: Increased Frequency

The Yuxinou railway is one of the earliest and most important infrastructure projects in the plan to position Chongqing as the international logistics hub for China’s inland cities. Spanning more than 11,000 km, it is the first CR Express coming into operation. It starts from Chongqing and ends at Duisburg, Germany, crossing countries along the BRI routes, including Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus and Poland. This international container freight railway is one of the first CR Express lines to support China’s implementation of regular two-way transportation with Europe. Trains are currently running on a regular weekly basis.

According to Yuxinou (Chongqing) Logistics, train frequency on the Yuxinou railway has increased from 17 runs in the first year of operation to 663 in 2017, a period of seven years, and is expected to reach the target of 1,000 runs per year in 2018.

Since its launch in January 2011, more than 1,500 runs have been made along the Yuxinou railway, representing a quarter of the total train runs made along the seven CR Express lines across the country. Over the years, significant improvement has been made in the uneven frequency between the outbound and inbound trains. While outbound trains constituted more than 90% of the total runs in the first four years, this ratio has dropped and has kept below 70% in recent years, reflecting the gradual improvement in operational efficiency.

Apart from the gradual increase of train runs year by year, the area served by the Yuxinou railway has also been expanding continuously. In addition to the initial Xinjiang Alashankou Port, the Yuxinou railway has developed three more entry and exit ports at Khorgas, Inner Mongolia’s Manzhouli and Erenhot in recent years. So far, its assembly points and distribution points have been extended to over 30 cities in more than 10 countries, including Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan.

The journey time along Yuxinou railway has been further reduced since the Lanzhou-Chongqing line came into full operation in September 2017. The Lanzhou-Chongqing line runs from Lanzhou in Gansu to Chongqing via the provinces of Gansu, Shaanxi and Sichuan, connecting the southwest and northwest regions of China. Through the connection of the Lanzhou-Chongqing line with the Yuxinou railway, the route between Chongqing and Lanzhou has been shortened from some 1,400 km to around 800 km.

As the Yuxinou railway no longer needs to pass around Xi’an, the running time along its whole course is further reduced. At the initial stage of its operation, it took about 15 days for a train to run from Chongqing to Duisburg. It was subsequently reduced to some 13 days as railway operations became smoother. Now, with the opening of Lanzhou-Chongqing railway, the journey time of Yuxinou’s whole route has been further cut to 12 days, helping to reduce transport costs.

Diverse Cargo Mix in Transit

Due to technical and historical reasons, rail freight transport between China and Europe had a later start than sea and air freight. As a result, the cargo mix on the Yuxinou railway as China’s first CR Express line was mainly confined to one product – laptop computers – during the initial stage.

Over its seven-year plus operating period Yuxinou has secured more cargo sources and the goods transported have gradually diversified. Today, the cargo mix exported to Europe via Yuxinou has been expanded to cover, for example, machinery and equipment, automobiles and parts, and coffee beans, whereas the incoming freight includes automobiles and parts, machinery and equipment, cosmetics, milk powder and other maternity and baby products from various European countries.

In 2016, the Yuxinou railway officially introduced China’s first designated train for the parallel import of completed vehicles, where vehicles of high-end European brands were transported directly from Germany to Chongqing, enriching the cargo mix of inbound trains. According to the Chongqing Entry-Exit Inspection and Quarantine Bureau, the quantity of completed vehicles imported through Chongqing railway entry port has been on the rise year by year since its designation as the first entry port for completed vehicles in the western inland region in 2014. It now ranks first among all inland ports in China in terms of the quantity and types of completed vehicles imported.

In early 2018, the Ministry of Commerce announced that Chongqing railway port will become one of China’s trial zones for the parallel import of vehicles. The related concession policy for pioneers and trial zones is expected to further promote the development of the parallel vehicle import sector in Chongqing.

With the new edition of the Agreement on International Goods Transport by Rail coming into effect in July 2015, the old restriction prohibiting the transportation of postal transit items by international direct freight trains was removed. The services provided by the Yuxinou railway have been extended accordingly to cover the transportation of international parcels. After a number of trials, Yuxinou railway became the first CR Express line designated for the transportation of international parcels in 2016. Subsequently in 2017, outbound transportation of international parcels was included in its regular schedule with a daily parcel load up to 15,000 pieces.

To further promote its operation in international parcel transportation, the Yuxinou railway will embark on the inbound transportation of parcels on a trial basis in 2018. A railway port centre for the International Mail Exchange Bureau will be set up in Chongqing Western Logistics Park to deal with mail processing, the related customs clearance and border clearance procedures, which will further promote Chongqing’s role as a distribution centre of international parcels transported by rail and a port hub.

As cross-border e-commerce mostly involves the export of small parcels similar to the shipping of international parcels, Yuxinou railway’s engagement in international parcel transportation will also spur the rapid development of cross-border e-commerce and related industries. In September 2017, China’s first designated cross-border e-commerce train came into operation on the Yuxinou line. Since then, cross-border e-commerce no longer relies solely on the consolidation of container loads for rail transport, but can use the services of designated e-commerce trains. Faster than sea transport and cheaper than air freight, rail transportation through Yuxinou provides an alternative for cross-border e-tailers.

With the ongoing development of the Yuxinou railway, the rail-based transportation system will be further optimised. It is thus expected that the cargo mix of Yuxinou will be more diversified. By venturing into high value-added business, such as cold chain transport or the transportation of pharmaceutical products and timber that require more sophisticated logistics services, the Yuxinou railway is set to attract more cross-border cargo sources.

The Yuxinou+ Model

Since its launch seven years ago, the service offered by the Yuxinou railway has improved in many ways, including shorter journey times, wider geographic coverage and the capacity to handle a more diverse cargo mix. Overall, it is seen as providing an example of best practice to other CR Express lines across the country. As the line has become more developed, efforts have been made to facilitate its interchange with other freight transport channels. Ultimately, the aim is to establish a multi-modal freight transport system with Yuxinou as its hub. More recently, the China-Singapore (Chongqing) Demonstration Initiative on Strategic Connectivity was launched in Chongqing as a means of promoting interconnectivity between rail, air, sea and road transport systems. Overall, it is planned to establish Chongqing as western China’s multi-modal transport hub.

For its part, the Yuxinou+ multi-modal freight transport system represents a new, flexible international logistics option, one particularly designed to meet the needs of China-Europe trade exchange. As the BRI project continues to unfold, the Yuxinou line looks set to play a still greater role in China-Europe trade connectivity, reinforcing Chongqing’s role as western China’s key logistics hub.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By ICBC Standard Bank and Oxford Economics

1.1 Connectivity and our index

In essence, B&R is a multi-generational project that looks beyond infrastructure and is, instead, “rooted in a shared vision for global development” While tackling the infrastructure deficit is a necessary step to unleash inclusive economic development, measuring broader economic benefits is of equal, if not more profound, importance. As a practical matter, both the implementation and longevity of B&R will depend on the realisation of broad mutual benefits across B&R participants. The China Connectivity Index (CCI) is specifically designed to capture these broader economic benefits by quantifying the dynamics of bilateral connectivity between B&R countries and China.

The CCI is a first of its kind research tool offering a unique solution to the challenge of tracking the evolution of the still nascent B&R project. The purpose of the CCI is to build out a dynamic evidence base from which investors and policy makers can assess the high level themes and challenges that emerge from the massive efforts of B&R.

As the first CCI white paper, it is natural and necessary to examine the index from a retrospective viewpoint. We take this opportunity to explore, through the lens of the CCI, what trends and insights can be distilled from the changing nature of China’s connectivity to the B&R countries over the last 10 years. Chapter 2 presents the index framework and previews the headline results of the inaugural index. In Chapter 3, we discuss the key insights from the CCI based on in-depth empirical research. Chapter 4 looks forward to identify themes critical for future B&R developments, and sets out our vision to establish B&R thought leadership…

4. B&R connectivity in the future

Working in partnership with B&R governments to tackle the infrastructure deficit is a key objective for China in the years ahead. The Chinese government is committing substantial funding to several new investment vehicles, as well as bolstering existing institutions with a new mandate to support B&R. It is important to note the bulk of this funding has yet to be deployed, so current CCI results reflect little of this investment.

To support infrastructure development outside of China itself the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) has the potential to be the most powerful. The AIIB is a multilateral organisation, with 52 members, including several outside of Asia. Total capitalisation of the bank is US $100 billion, with China providing a quarter. The bank has a mandate to finance “Asia-related” infrastructure in member economies. The Bank lent approximately US $1.7 billion in 2016 to nine projects across Asia and the Middle East.

Elsewhere, the New Development Bank (NDB, previously the BRICS Development Bank) also has a mandate to lend for projects that promote infrastructure and development with a significant impact in member countries. Three of the five member economies of the NDB are part of B&R (China, Russia and India), and the bank’s Vice President said in 2016 that expansion to new members was a priority.

China is also acting through new investment funds, over which it will have more autonomy. The Silk Road Fund is a Chinese state-owned investment fund, set up in 2014 with an endowment of US $40 billion from the Chinese government. The fund’s mandate is to upgrade infrastructure along the B&R, and it has so far made three investments – most significantly in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, which is discussed in more depth below. In 2016, China set up the Sino-CEE Fund, with an endowment of €10 billion and the aim to leverage a further €50 billion. The fund will focus on Central and Eastern Europe but could extend its operations to other regions for projects supporting China-CEE connectivity.

China has also increasingly permitted the China Development Bank (CDB) to start invest overseas in recent years. The bank was founded in 1994, and at end-2015 had RMB 9.2 trillion (US $1.4 trillion) in loans outstanding. However, the CDB is likely to remain primarily focussed on domestic economic development―supporting transition away from heavy industry in the north-east and financing economic development in western provinces.

Chinese commercial banks are also increasing their financing to B&R projects, supported by official co-financing. For example, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is a network of connected projects boosting maritime, rail and road connectivity between the two countries, as well as upgrading utilities infrastructure in Pakistan. Total financing committed across the CPEC is expected to amount to US $62 billion over the period from 2015-2030, coming from a wide range of sources, including commercial and multilateral banks. Analysis of the “big four” Chinese state-owned commercial banks suggests they lent a total of US $90 billion into B&R economies in 2016. However, it not clear how much of this lending related to the infrastructure related objectives of the B&R initiatives, as opposed to more standard commercial activity.

Finally, the initiative has also been formally recognised by the global development financing community. At the B&R summit, a Memorandum of Understanding was signed by the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the New Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the World Bank, the European Investment Bank, and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. At the summit, Jean-Christophe Laloux, Director-General of the European Investment Bank said “We appreciate the tremendous efforts of all involved and recognise the clear the leadership that China has shown to develop this key initiative”.

5. Conclusion

Much has already been achieved in boosting B&R connectivity, even prior to the formal announcement of the initiative in 2013. B&R exports are accounting for a steadily rising portion of China’s demand in some key areas, allowing B&R economies to tap into China’s rapid growth. But within B&R there have been some important shifts in relative connectivity between regions – largely driven by changing priorities for the Chinese economy.

The outlook is clearly positive for the future of B&R connectivity. Resources are being marshalled for a substantial financial stimulus to boost infrastructure spending across the B&R regions, while trade, investment and financial sector policies are also being liberalised to unlock potential economic flows.

We expect China’s domestic economic agenda to continue to be a key factor in connectivity developments looking ahead. The growing importance in recent years of services trade, supply chain connectivity, and outward investment in higher value-added economies are all set to persist. So while ASEAN economies may remain the most-connected with China, those in CEE and key tourism destinations are likely to close the gap. Connectivity with commodity-based Middle Eastern and Central Asian economies may fall further if these countries fail to diversify into sectors better-aligned with China’s own priorities.

Trends in the wider global economy should be supportive of B&R connectivity in the years ahead. After several years of very slow global trade growth, data from the first half of 2017 suggests a reinvigoration of global trade activity. With an increasingly-positive economic outlook across many developed and emerging economies, global trade flows and demand for Chinese goods and services should strengthen in the coming years.

But several key sources of risk remain, particularly with respect to an uncertain global geopolitical landscape. An increase in protectionism in key advanced economies could prevent market forces from driving global trade growth, and therefore China’s trade connectivity. In the Middle East, diplomatic tensions could undermine the freedom of movement of goods and people across a key region for China-Europe trade. And slower-than-expected growth in China would cut resources available for B&R investment – even as it makes better connectivity more crucial. Finally, from a political perspective, it will be important to ensure the consensus over economic connectivity between China and B&R being mutually beneficial is sustained, and that partner economies see plenty of direct economic gain.

The China Connectivity Index will be a crucial tool in the years ahead. CCI will remain the key resource for B&R stakeholders seeking to stay informed of connectivity enhancements in the years ahead. This report will be updated on a semi-annual basis, reviewing latest trends in China-B&R economic connectivity, as well as progress made in delivering against policy pledges. Moreover, our work on China Connectivity will be complemented by an ongoing monitoring of economic health in B&R economies. For our initial assessment of economic health in B&R, please see the complementary paper accompany this China Connectivity report.

Please click to read full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

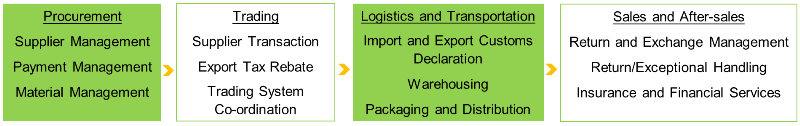

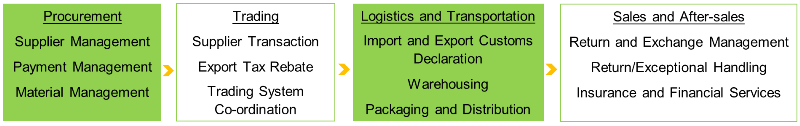

Many enterprises on the Chinese mainland are actively investing in factory automation in order to mitigate labour shortages and enhance competitiveness by turning out higher quality products. In a bid to improve added value and competitiveness, some enterprises pursue high-tech business, while others adopt a brand-building strategy. But the division of roles and responsibilities among different industries is increasingly refined, with domestic and global supply chains becoming more complex. As a result, many businesses need to source service support from third parties to better connect various elements of their operations. Improved connections from research and development, to design, production, sales and after-sales service, as well as enhanced supply chain management, can help companies’ transformation and upgrade strategies.

As pointed out by Shanghai Miller Supply Chain Management Co Ltd (Miller) during a recent interview[1], the mainland traffic and transportation network has come a long way in recent years and efficient logistics has become an integral part of many industries’ operation. In the competitive mainland logistics market, some enterprises use a low-price strategy, whereas others pursue a value-add approach, providing clients with comprehensive supply chain management in addition to logistics supports.

Many companies are making use of transport and procurement platforms in the Yangtze River Delta, Pearl River Delta and even Hong Kong for sourcing or transit at different locations. This enables businesses to secure a wide range of production materials, handle movement of components from different sources and distribute finished products to different destinations. This is particularly the case with the import and export of higher-value products, including high-end electronic parts, where businesses tend to make use of efficient international air transport hubs, such as Hong Kong, to send goods to the mainland or export them to overseas markets.

As Hong Kong is one of Asia’s major electronic parts and components distribution centres, many companies dealing in these items have set up offices there for procurement and transportation of various kinds of electronics through the city. Specific freight and logistics routes vary, depending on individual companies’ specific operation.

According to a Miller executive, the company not only runs logistics facilities in the Shanghai Pilot Free Trade Zone and Pudong Airport, but has also set up branch offices and transit warehouses in Shenzhen and Hong Kong. This enables Miller to support its clients with a third-party freight and logistics network, both domestically inside the mainland and internationally. In addition, it provides one-stop supply chain management through its mainland and Hong Kong network.

General Supply Chain Services Required

To assist mainland enterprises’ business upgrade strategies, Miller also helps manufacturer clients to identify appropriate technology and production materials, as well as to source key parts and components, including the referral of overseas suppliers and technology partners. It also provides related procurement management services, such as arranging international payment, transaction and export tax rebates. At present, supply chain management services provided by Miller cover the Chinese mainland, Europe, the Americas, Japan and Korea, serving businesses in food products, aircraft parts and components, medical instruments/equipment and a wide range of electronics.

Note: For details of the company interviews conducted jointly by HKTDC Research and the Shanghai Municipal Commission of Commerce, please refer to other articles in the research series on Shanghai-Hong Kong Co-operation in Capturing Belt and Road Opportunities.

[1] Miller was interviewed jointly by HKTDC Research and the Shanghai Municipal Commission of Commerce in Q1 2018.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

In view of intense market competition and the need for industrial transformation and upgrade, China is encouraging enterprises to enhance their product R&D capabilities and production technologies, while adopting innovative supply-chain management practices. In October 2017, for example, the State Council issued its Guiding Opinions on Actively Promoting Supply Chain Innovation and Application. The hope is that, by 2020, this initiative will see all of China’s major industrial sectors benefitting from new technologies and new supply chain development business models, as well as having access to smart supply-chain systems. [1]