Chinese Mainland

By Dr. Tony Liu, Center for Comprehensive Japan and Korea Studies, National Chung Hsing University

With China's promotion of the One Belt One Road initiative, consisting of the Silk Road Economic Belt and Maritime Silk Road, at the APEC summit in 2014, where the international community once again focused its attention on Central Asia. Despite similar emphasis on the strategic importance of land and sea, much attention has been centered on the continental economic belt that seeks to cross the Eurasia continent by extending westward from China's historical city Xi'an, through Central Asia and into Europe. As a connecting point in the One Belt One Road, Central Asia is critical to China's Go Out strategy. Along with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, China clearly demonstrates an aspiration to establish its political and economic influence in Central Asia.

In terms of geopolitics, while China's activities in Central Asia remain distant for Japan, its expansion into the region entails strategic consequences that may severely challenge Japanese foreign policy and security. Although Japan and China have yet to clash directly in Central Asia, incongruent interests between the two powers already hint at the potential for friction in the region. This article is an attempt to understand the impending possibilities for conflict between Japan and China in Central Asia. By identifying and contrasting Tokyo and Beijing's respective interests and foreign policies in Central Asia, this author suggests the formation of a new battlefield for Sino-Japanese competition based around institutional leadership, regional influence and foreign assistance. Three scenarios for conflict are proposed as developments that may destabilize regional order and reinforce tensions between Japan and China in the near future.

Introduction

Since the turn of the century, Central Asia has played an increasingly important role in global geopolitics. While part of the region's significance stems from Harold Mackinder's Heartland Theory, Central Asia's strategic location and rich energy and market potential make the region a fitting arena for great power politics. In 2001, international attention was drawn to Central Asia with the establishment of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). As an initial mark of China's expanding influence in the new century, the SCO sounded an alarm for Japan. In response, in 2004, Japan established the Central Asia plus Japan Dialogue in an effort to balance China's growing influence in Central Asia.

In light of the Shinzo Abe administration's re-initiation of the Central Asia plus Japan Dialogue in 2014, this paper seeks to address growing strategic tensions in Central Asia between Japan and China. The analysis will be carried out in four parts: Part one reviews the significant role of Central Asia in contemporary geopolitics; part two and part three turn to China and Japan's strategic interests and foreign policies in Central Asia respectively; and part four proposes three scenarios for strategic competition between Japan and China in Central Asia in light of recent developments. This paper concludes with some insights into the development of Sino-Japanese relations in the near future.

Please click to read full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Alicia Garcia-Herrero, Chief Economist for Asia Pacific at NATIXIS; Adjunct Professor, Department of Economics, The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology

Jianwei Xu, Beijing Normal University

1. Introduction

It has been three years since China launched its grand plan of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Although Chinese government has put great efforts to push for the plan, not only inserting related topics in most of its diplomatic events, but also promoting more funded projects in the area, domestic and international concerns regarding the feasibility of the plan have never diminished. Against the back drop, an economic overview of the BRI becomes very important to understand the feasibility of the plan.

To this end, we will discuss the economic progress of the BRI from the trade, investment and financial perspectives, respectively. Trade is most accessible field for China to breakthrough as it can be instantly affected by short-term policies such as removing tariff or non-tariff barriers. If China has established a closer relationship with the BRI area, trade between the two should move upward in a short period. Our findings also confirm the rapid progress in trade, though the development was not equally distributed in the area, with the ASEAN, Middle East, South Asia and Russia constitute the largest trade share with China. Our analysis on the BRI’s spillover effect on the US and the EU reveals that the BRI plan poses actually very little substitution effect but under some scenarios even positive impact on the EU-China trade. We especially assess the impacts on the EU, which sits at the other end of the BRI area, and find that better connectedness within the BRI area will bring higher economic benefits to the EU than free trade agreements.

Compared with trade, investment needs longer time spans to deliver fruits, especially when most of the BRI area is still classified as risky destination and long-term investment takes time to push forward. Needless to say, the BRI area is attractive for nearly every international participant. Our analysis indicates that the progress in investment has been so far discouraging. Although the overall level of China’s oversea investment in the area has been picking up in recent years, the relative share compared with the other destinations actually declined. Chinese oversea investment focuses on the developed world, especially Europe. This can partly be explained by the higher risk associated with many countries in the BRI area. But it is too early to be pessimistic about the plan. It is possible for the trend to reverse in the future. With the rising protectionist atmosphere in the EU and the US, as well as pressure from Chinese regulators to discourage investing in non-productive fields in the developed economies, China is likely to divert more investment to the BRI area, which needs close watch.

Finance is the most difficult part. Although China has set up the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the Silk Road Funds, etc., to support the plan, it is far from enough. Various estimates indicate that there is still a big gap to fully fulfil the needs for finance in the BRI area. In fact, the EU has long been an important credit supplier in the BRI area. To better facilitate the grand plan, China must seek international cooperation, especially with the EU.

Admittedly, it is also too hasty to extend our assessment as the final one because it is only three years since the start of the plan, while most of these projects may take a long time to realize their benefits. But our mid-term assessments at least show that it is not easy for China to deal with such a broad area with countries of very different development structures, cultural and political systems. To enhance the efficiency of the BRI, China may consider taking a strategic attitude to implement the plan: first focus on certain low-risk countries, such as the ASEAN countries and Russia, and then extend it to more if their economic conditions have improved.

Last but not the least, the prospect of the BRI hinges not only on the BRI area itself, but how China’s relationships with the US and the EU evolve. If the US started to befriend China and two territories can agree to put aside their conflicts, China may have more incentive to push stronger for the BRI in the area. Otherwise, the development of the BRI will less likely to be a priority for china. The EU also plays a pivotal role in the plan, as some of its members are directly included as BRI countries and the others stay at the other end of the area. If China could gain more confidence from its cooperation with the EU, and the EU is willing to join efforts in finance and investment, the development of the BRI will undoubtedly accelerate…

3. Unbalanced improvement in China’s trade with the BRI area

The Belt and Road countries, despite their dispersion in terms of politics and culture, have become an increasingly important trading partners for China, especially destinations for Chinese exports. Back to 2000, the OBOR countries only constitutes 13% of China’s exports and 19% of China’s imports, but both shares have reached up to 27% and 23% by 2015, with an apparent bigger winner being exports.

Undoubtedly, given the broad dispersion in the stage of development as well as politics and culture, China’s trade with the Belt and Road area also varies across the region. ASEAN, Middle East, South Asia and Russia are China’s largest four trading partners in the region. The other countries are small in terms of economic magnitude, accounting for only three percent of China’s total trade…

4. Investment

One important aspect of China’s ambitious BRI plan is to invest more projects in this developing area to gain capital benefits as its domestic capital return has declined dramatically. Since the announcement of the BRI in 2014, China has accelerated its project negotiation with the BRI area relative to the other countries. China’s signed contract value was only 43780 USD million on April 2014, accounting for 38 percent of China’s total oversea signed contracts, but the accumulated contract value since then has climbed up to 781110 USD million in July 2017, which constitute nearly 50% of the total accumulated signed contract value.

However, it is too early to say that real progress has been made for investment in the OBOR area. Although signed contract value increased dramatically, the accumulated completed contract in the region increased at a relatively slower pace, with its share over the total completed contract only slightly increased from 45% to 46%. This may reflect the fact that most of the existing signed contracts are either ongoing or not started yet. Chart X further shows that the proportion of the accumulated oversea nonfinancial direct investment in the BRI area has actually decreased since 2014 from 15% to 11%. As such, the implementation of the BRI projects seems still lack efficiency…

5. How to finance BRI? Headwinds ahead

The implementation of the BRI includes a number of grand infrastructure plans. But this is easier said than done. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) recently increased its already very high estimates of the amount of infrastructure needed in the region to 26 USD trillion in the next 15 years, or 1.7 USD trillion per annum. The great thing about the China driven Belt and Road initiative is that it aims to address that pressing need, especially in transport and energy infrastructure. The a-priori is that the financing will be there thanks to China’s massive financial resources.

Such a-priori was probably well taken when China was flooded with capital inflows and reserves had nearly reached USD 4 trillion and needed to be diversified. In the same vein, Chinese banks were then improving their asset quality, because the economy was booming and bank credit was growing at double digits. However, the situation today is very different. China’s economy has slowed down and banks’ balance sheets are saddled with doubtful loans, which keeps on being refinanced and does not leave much room for the massive lendings needed to finance the Belt and Road initiative. This is particularly important as Chinese banks have been the main lenders so far (China Development Bank in particular with estimated figures hovering around USD 100 billion and Bank of China has already announced its commitment to lend USD 20 billion). Multilateral organizations geared towards this objective certainly do not have such a financial muscle. Even the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), born for this purpose, has so far only invested USD 1.7 billion on Belt and Road projects. As if this were not enough, China has lost nearly USD 1 trillion in foreign reserves due to massive capital outflows. Although USD 3 trillion of reserves could still look ample, the Chinese authorities seem to have set that level as a floor below which reserves should not fall so that confidence is restored. This obviously reduces the leeway for Belt and Road projects to be financed by China, at least in hard currency.

Against this background, we review different financing options for Xi’s Grand Plan and their implications. The first and least likely one, is for China to continue such huge projects unilaterally. This is particularly difficult if hard-currency financing is needed, for the reasons mentioned above. China could still opt for lending in RMB, at least partially, with the side-benefit of pushing RMB internationalization. However, even this is becoming more difficult…

6. Conclusion

This paper makes a mid-term assessment for China’s BRI from the perspective of trade, investment and finance, respectively. We find that trade has made significant progress in the BRI area in the past three years, but the development was not equally distributed in the area. The progress in investment has been so far more discouraging. Although the absolute level of China’s oversea investment in the area has been picking up in recent years, the relative share compared with the other regions actually declined. The financial aspect of the BRI is also uncertain. China has injected its own funds through various institutions, but various estimates indicate that there is still a big gap to fully fulfil the needs for finance in the BRI area, which requires more international cooperation.

All in all, China’s progress in the BRI is still on the way. The future of the BRI may continue to go in a very unbalanced direction, especially towards ASEAN and Russia. The actual investment in this area is also expected to increase and upgrade with more technology, but this hinges not only on the BRI area itself, but how China’s relationships with the US and the EU evolve. More importantly, China cannot finance the BRI by itself and needs to cooperate with the EU and US for the development of the BRI.

This article was first published by HKUST Institute for Emerging Market Studies. Please click to read the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

With China and Thailand identifying joint economic objectives, Beijing has loosened its purse strings still further.

Following the Thai Government's recent formal adoption of the EEC (Eastern Economic Corridor) Act, it's now all systems go for the country's Thailand 4.0 development strategy, a programme expected to neatly dovetail into the objectives of China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Moves to more closely align the Thai economic strategy with China's own international infrastructure development and trade facilitation programme began back in 2017, with the growing trade between the two countries now helping to oil the requisite bureaucratic wheels.

In a formal address last month, Prayut Chan-o-cha, the Thai Prime Minister, highlighted the existing synergy between the two developmental blueprints, saying: "It's natural, logical, and mutually-beneficial that the EEC should link-up with the BRI, as well as with other regional initiatives, such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) or even the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)."

In order to fully capitalise on these emerging synergies, the two countries have already agreed to establish a joint economic development board. Billed as the Sino-Thai Joint Think Tank Forum, the body held its first meeting in Beijing earlier this month in association with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), with 80 senior academic and government officials from both countries jointly considering how best to capitalise on those economic initiatives deemed to be of mutual benefit.

Speaking after the conclusion of this inaugural session, Gao Peiyong, CASS' Vice-president, said: "Thailand's innovation-driven development program is hugely compatible with the goals of the BRI. Both countries have a genuine need to boost their international connectivity, while also promoting industrial upgrading.

"I see infrastructure, telecommunications, the digital economy, energy and internet technology as the five key areas for bilateral cooperation. I believe these should be the two countries' cooperative priorities for the next five years at least."

In terms of the actual EEC programme, at its core is the development of five economic clusters spread across three of the country's eastern provinces – Chaochoengsao, Chonburi and Rayong. Of the three, the Eastern Airport City Zone is one of the initial priorities. Centered around an upgraded U-Tapao International Airport, the focus will be on developing the facilities required to boost the throughput of tourists, with mainland-originated visitors now the single largest segment of Thailand's tourism sector.

A clear second priority is the Eastern Economic Corridor of Innovation (EECi), a large research and development park set to be sited in Rayon's Wangchan Valley. This will be followed by the development of the Digital Park Thailand (EECd), the Smart Park and the Hemaraj Eastern Seaboard Four Industrial Estate. In order to sustain and service these initiatives, a number of rail transportation projects, air terminal extensions and port enhancements will be initiated simultaneously.

China is already set to play a huge role in bringing many of those initiatives to fruition. In particular, it has taken a lead in the implementation of the BRI-backed Bangkok to Southern China via Laos high speed rail link. On top of that, to date more than 80 Chinese companies that have established manufacturing facilities, research centres or operational hubs in the specially-designated Thai-Chinese Industrial Zone.

As of the end of 2016, China's investment in the EEC had already exceeded US$30 billion. Now, with the more formal alignment of the two nation's development schemes, this figure is expected to soar over the coming months.

Geoff de Freitas, Special Correspondent, Bangkok

Editor's picks

Trending articles

中國社會科學院世界經濟與政治研究所宋爽

隨著11月29日李克強總理結束對匈牙利正式訪問,中國與中東歐國家合作又上層樓。中國─中東歐"16+1合作"機制已建立五年有餘,合作力度不斷加大,已成為具有重要影響的跨區域合作機制。五年來,中國企業對中東歐16國的累計投資從30億美元增長到90多億美元,中國從中東歐國家進口農產品的年均增長率超過10%,貝爾格萊德跨多瑙河大橋、匈塞鐵路、波羅的海高鐵等一批標誌性的基礎設施項目相繼啟動。作為投資、貿易、基礎設施建設的重要支撐,金融合作在"16+1合作"平台下也穩步推進,並取得豐碩成果。

一、五年來金融合作碩果累累

金融合作一直是"16+1合作"的重要方面,在首次中國─中東歐國家領導人會晤上就確定了設立總額100億美元專項貸款、發起設立"中國─中東歐投資合作基金"和探討貨幣互換、跨境貿易本幣結算等三項重要的金融合作舉措。此後,每年中國與中東歐國家領導人會晤時都會繼續強化金融合作,使雙方的金融合作進一步拓展至互相投資對方銀行間債券市場、在中東歐國家建立人民幣清算安排、成立中國─中東歐國家銀聯體等多樣領域。如今,"16+1合作"機制下的金融合作已經在金融機構、金融市場、投資基金、貨幣互換與本幣結算、多邊開發性金融和金融監管等方面取得顯著進展。

在金融機構互設與合作方面,中國銀行已先後在波蘭華沙、匈牙利布達佩斯和捷克布拉格等地設立分行,在塞爾維亞設立分支機搆;中國工商銀行在華沙和布拉格設立分行,並於2016年11月成立中國-中東歐金融控股公司;中國建設銀行也在華沙設立分行。此外,中國銀聯與中國銀行匈牙利分行於2017年1月合作發行了匈牙利福林、人民幣雙幣芯片借記卡。與此同時,中東歐國家金融機構也開始進入我國市場,匈牙利儲蓄商業銀行就於2017年10月在北京設立了代表處。

在投資基金方面,中國─中東歐投資合作基金一期順利展開,並啟動二期基金募集。中國─中東歐投資合作基金由中國進出口銀行作為主發起人,有限合夥人還包括匈牙利進出口銀行等中東歐國家金融機構,重點支持中東歐16國基礎設施、電信、能源、製造、教育及醫療等領域的發展。一期基金於2014年年初正式運營,封閉金額為4.35億美元,已在波蘭、捷克、匈牙利、保加利亞等國展開投資。在本屆中國─中東歐國家經貿論壇上,李克強總理宣佈二期基金已完成設立,募集資金10億美元。

貨幣互換與本幣結算也是中國與中東歐國家金融合作的重點方向。在貨幣互換方面,中國人民銀行在2013年9月分別與匈牙利央行、阿爾巴尼亞央行簽署雙邊本幣互換協議,此後又於2016年6月與塞爾維亞央行簽署中塞雙邊本幣互換協議,2016年9月與匈牙利央行續簽中匈雙邊本幣互換協議。在本幣使用方面,中國銀行匈牙利分行於2015年6月獲准擔任匈牙利人民幣清算行,成為中東歐地區首家人民幣指定清算行。

在多邊開發性金融合作方面,亞洲基礎設施投資銀行(亞投行)一直是中國與中東歐合作的重要平台。繼2016年6月波蘭成為亞投行正式成員後,羅馬尼亞於2017年5月成為意向新成員,匈牙利則于6月成為正式成員。此外,國家開發銀行(國開行)倡議設立的"中國-中東歐銀聯體"也於2017年11月正式成立,國開行將提供20億等值歐元開發性金融合作貸款。在此次中國─中東歐國家領導人會晤期間,14家中東歐國家金融機構與國開行簽署合作協議,加入中國─中東歐銀聯體。

在金融監管合作方面,我國各級監管部門與中東歐多國相關部門達成了監管合作協議。中國人民銀行已經與捷克國家銀行簽署合作諒解備忘錄,中國銀監會與捷克中央銀行、立陶宛中央銀行、匈牙利中央銀行、波蘭銀行監管委員會等主要中東歐國家金融監管部門簽署了監管合作諒解備忘錄和監管合作協議,中國證監會與羅馬尼亞國家證券委員會、立陶宛銀行、波蘭金融監督管理局等簽署了證券期貨監管合作諒解備忘錄。此外,2015年5月在上海舉行了中亞、黑海及巴爾幹地區央行行長會議組織第33屆行長會,2018年還將在布達佩斯舉辦中國-中東歐國家央行行長會議。

二、與"一帶一路"倡議相輔相成

雖然中國-中東歐"16+1合作"機制的建立早於"一帶一路"倡議,但是如今二者已經有機結合,相輔相成。正如習近平主席多次指出的,要將"16+1合作"打造成"一帶一路"倡議融入歐洲經濟圈的重要承接地,推動“一帶一路”國際合作高峰論壇成果率先在中東歐落地。在此次中國-中東歐國家領導人會晤的講話中,李克強總理強調了做大經貿規模、做好互聯互通、做強創新合作、做實金融支撐和做深人文交流五個重要合作方面,與"一帶一路"倡議的"五通"內容一脈相承,異曲同工。

一方面,"16+1合作"逐漸成為"一帶一路"倡議的"標杆",對"一帶一路"建設具有推動和示範作用。由於地處"一帶一路"北線遠端,中東歐國家雖然經濟制度穩定、營商環境良好,在"一帶一路"建設推進過程中卻常常面臨著鞭長莫及的窘境。"16+1合作"為中國與中東歐國家建立了重要的跨區域機合作機制,不僅有助於推動“一帶一路”建設在中東歐次區域展開,還能夠對"一帶一路"倡議的實施產生示範效應。就貸款和投資基金而言,在“16+1合作”平台上提出的專門面向中東歐國家的100億美元專項貸款和中國-中東歐投資合作基金,就很大程度上彌補了中國向中東歐國家金融支持機制不足的問題,推動了一批基礎設施建設、高新技術、綠色經濟項目的開展,成為"一帶一路"建設的標杆項目。就債券市場而言,波蘭和匈牙利先後在我國銀行間債券市場發行熊貓債,佔據目前在中國發行熊貓債的三個"一帶一路"沿線主權國家的兩席,對沿線國家進入我國債券市場融資支持"一帶一路"建設起到示範作用。此外,"16+1合作"機制下推動的貨幣互換、開發性金融和金融監管合作,都對中國在"一帶一路"沿線國家推進資金融通具有重要的示範意義。

另一方面,"一帶一路"倡議已經逐漸成為"16+1合作"的戰略支撐,對"16+1合作"機制深化帶來機遇、提供支持。"16+1合作"作為中國開展的眾多跨區域合作機制之一,在"一帶一路"倡議提出後迎來新機遇,金融合作的理念和形式不斷創新。例如,2016年11月工商銀行設立中國─中東歐金融控股有限公司,並將發起設立100億歐元的中國─中東歐基金,以彌補雙方產能合作的融資短板。2017年11月,國開行牽頭發起設立中國─中東歐國家銀聯體,成為"16+1合作"框架下重要的多邊金融合作平台,國開行將提供20億等值歐元開發性金融合作貸款。同時,"一帶一路"倡議下的部分金融資源也被用於支持"16+1合作"機制。2016年的《中國─中東歐國家合作裡加綱要》中就指出,鼓勵包括絲路基金在內的中方金融機構積極拓展在中東歐地區的投資與合作,為中國-中東歐國家合作提供金融支持。2017年的《中國─中東歐國家合作布達佩斯綱要》則進一步提出,歡迎中國國家開發銀行、進出口銀行設立"一帶一路"專項貸款、絲路基金與歐洲投資基金推動設立中歐共同投資基金,將相關資金用於中國─中東歐國家有關項目。

三、繼續深化“16+1合作”金融機制

中國與中東歐國家"16+1合作"機制已經搭建起良好基礎,取得了豐富成果。展望未來,雙方應基於各自的優勢和需求,繼續推進互利共贏的新型多雙邊合作關係。在金融層面,中國應與中東歐國家一起繼續創新合作方式,整合各類金融工具,建立更加全面、深入的金融合作機制。

首先,加強對中國─中東歐國家經貿合作的金融支持。"深化經貿金融合作"是此次中國─中東歐國家領導人會晤的主題之一,足見經貿合作的重要意義。長期以來,中國在與中東歐國家貿易中都處於絕對順差優勢,未來“平衡發展”必將成為雙方貿易合作的主題。隨著中國加大對中東歐國家在農業、食品、飲料等優勢產品的進口,我國金融機構可積極憑藉多年來在供應鏈金融、互聯網金融等方面積累的服務經驗,促進中東歐企業對中國的貿易便利化。同時,根據雙方國家貿易拓展進程,適時擴大中國與中東歐國家的貨幣互換和人民幣貿易結算,鼓勵中資銀行在中東歐國家設立更多跨境貿易人民幣結算中心,以降低匯率風險。此外,為服務中國與中東歐國家企業開展跨境貿易和投資活動,應鼓勵雙方金融機構互相進入開拓業務,並加強相關金融基礎設施的建立。

其次,擴展對中國─中東歐國家互聯互通的金融支持。李克強總理在此次中國─中東歐國家領導人會晤上指出,加快基礎設施建設是中東歐國家重要發展議程,也是"16+1合作"的優先方向。目前我國對中東歐國家基礎設施項目的資金主要通過銀行貸款和投資基金予以支持,下一階段可進一步拓展資本市場對中東歐國家基礎設施項目的融資支持,以引入更加多元化的資金,分散風險。一是繼續支持中東歐國家和企業到中國發行熊貓債,鼓勵融資主體將資金用於基礎設施建設。二是歡迎中東歐國家和企業利用國際債券市場發行絲路債券,特別是開展以人民幣計價的國際債券融資,推動"一帶一路"倡議國際債券市場融資機制的完善。三是發展中東歐國家債券市場的項目債融資機制,推動"16+1合作"下債券市場聯通,鼓勵在中東歐國家開展基礎設施建設的中資企業發行項目債。

最後,強化雙方在多邊開發性金融領域的合作。開發性金融應在跨區域合作中發揮先導作用,因此下一階段可繼續推進中國與中東歐國家的多雙邊開發性金融合作以及區域開發性金融機構之間的合作。第一,落實中國-中東歐銀行聯合體的作用,加強國家開發銀行與匈牙利開發銀行、立陶宛公共投資發展署等中東歐國家政策性銀行、開發性金融機構之間的多雙邊開發性金融合作。第二,加強亞投行與中東歐國家及相關區域多邊開發銀行的合作,歡迎更多中東歐國家加入亞投行,推動亞投行與歐洲復興開發銀行、歐洲投資銀行等區域開發性金融機構展開合作。第三,促進絲路基金和歐洲投資基金的合作,儘快落實雙方在促進共同投資框架備忘錄中提到的“中歐共同投資基金”,以支持歐洲及“一帶一路”沿線國家的中小企業與中國對接合作。

原文刊載於《財經國家週刊》2018年第3期,請按此閱覽原文。

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Edward Liu, Reed Smith Richards Butler, Senior Registered Foreign Lawyer

On 14 December 2017, the HKSAR government and the National Development and Reform Commission signed “Advancing Hong Kong’s Full Participation in and Contribution to the Belt and Road Initiative” (the ’Arrangement’). The Arrangement serves as a blueprint for Hong Kong’s further participation in the “Belt and Road Initiative” (the ’Initiative’).

The Arrangement has explicitly given its support to establish Hong Kong as an international legal and dispute resolution service hub for the Asia-Pacific region, hence to provide international legal and dispute resolution services for the Initiative. In order to practically implement the policies under the Arrangement and effectively realize a series of preferential policies towards Hong Kong, there is an imperative need for the negotiation between HKSAR government and legal industries to formulate specific proposals with detailed measures. Hence, the following foremost question for Hong Kong is, how to utilize the preferential policies under the Central Government’s overall jurisdiction and make full use of Hong Kong’s advantages under its high degree of autonomy in order to attract more mainland and overseas enterprises to use Hong Kong’s legal and dispute resolution service for disputes arising from commercial transactions related to the Initiative.

Encourage Chinese enterprises to choose Hong Kong as the dispute resolution venue

With the continuous growth of trade globalization and the Initiative, cross-border transactions become even more active. Hence, the number of disputes related to cross-border investments and international trade will increase accordingly. Imagine, in a transaction where one party is a Chinese enterprise and the other is an overseas enterprise, the overseas enterprise would always seek overseas arbitration institutions for settlement of any potential contract dispute. This is out of the concerns that overseas enterprises are generally incomprehensive of and are also lack of trust for mainland legal system and arbitration institutions. Nevertheless, for Chinese enterprises, equally, they will be uncertain about going overseas to settle disputes and also will have concern on the expensive legal costs. Under such circumstance, as the only common law jurisdiction in China and also under the protection of the Basic Law, as well as having the unique geographical location which allows for Western-Chinese cultural fusion, Hong Kong will undoubtedly be the ideal arbitration venue where both parties can accept.

As the bargaining power of Chinese enterprises in international trade and investments gradually increase, it becomes obvious to “stay at home” for dispute resolution regarding disputes in cross-border investments and transactions. Therefore, HKSAR government should establish a cross-department group, and actively seek to set up a cooperation mechanism with the relevant national authorities and organisations, which are respectively responsible for communications with the stated-owned enterprises and private enterprises. This group should aim to promote Hong Kong’s legal and dispute resolution services to all kinds of Chinese enterprises, and also encourage these enterprises to choose Hong Kong as the seat of arbitration for commercial disputes.

Provide more accommodation for the recognition and enforcement of Hong Kong arbitration awards in mainland

With the progression of the Initiative, it is envisaged that there will be more foreign-invested enterprises as well as wholly foreign-owned enterprises incorporated in Mainland China and especially in free trade zone (FTA). If both such companies agree to arbitrate overseas (including Hong Kong), according to the current Chinese legislation, the relevant arbitration awards are very likely not to be recognized and enforced by the Chinese courts because such awards do not have foreign affairs.

In 2015, the Supreme People’s Court (the ’SPC’) introduced a document with a view to providing judicial assistance and protection to the Initiative. In particular, the SPC indicated to support the parties to resolve the disputes in relation to the Initiative. Thus, HKSAR government should negotiate with the SPC and other mainland authorities to introduce relevant judicial interpretations to affirm that the enforcement of arbitration awards made in Hong Kong will not be affected due to its absence of foreign affairs under the abovementioned circumstances. If this result can be successfully realized, it will inevitably attract more commercial contracts to choose their arbitral seat in Hong Kong. Hence it will in no doubt enhance the status of Hong Kong as the international arbitration hub and help to improve the general business environment in Mainland China.

Please click to read the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By KPMG

The Hong Kong advantage

Hong Kong has a significant role to play in the development and success of the BRI. The city is regarded as one of the world’s freest economies, with a vibrant capital market, an extensive network of financial institutions, a robust legal system and an experienced pool of human capital. As an international finance centre and shipping hub, Hong Kong is well-positioned as a super-connector to the fast-growing BRI economies, and is set to play a prominent role in facilitating trade and investment, and encouraging cooperation in value-added sectors along the Belt and Road.

A policy agreement signed in December 2017 between Hong Kong and the National Development Reform Commission (NDRC) (referred to herein as the HK-NDRC Arrangement) is also set to expand Hong Kong’s role in the BRI.

Hong Kong’s key competitive advantages

1. Established international financial centre

The provision of financing and capital markets solutions represents a key driver of initial success for the BRI. At the outset, access to finance is a necessary element for the successful development of new infrastructure. If successful, this investment can stimulate further positive knock-on effects to sectors such as real estate, healthcare and industrial markets, leading to job creation, greater economic outcomes for BRI economies and a larger volume of global consumers.

One of the largest financial services centres worldwide, Hong Kong is well-placed to position itself as the long term partner of mainland Chinese and international groups seeking financial, banking, insurance and risk management solutions for BRI investment.

2. Connectivity with ASEAN

The ASEAN region comprises 10 Southeast Asian countries with a total population of more than 635 million,2 all of which are Belt and Road economies. With a young workforce, a strong growth track record, and a middle class population that is projected to reach 400 million by 2020,3 ASEAN represents an attractive investment jurisdiction for groups seeking to invest and conduct business along the Belt and Road.

For Hong Kong, its geographic proximity and cultural connections with the ASEAN countries make it an attractive investment platform for entry into these markets. In addition, many Hong Kong companies possess a deep, lengthy and well-respected track record of investment and business operations in ASEAN.

In November 2017, Hong Kong and ASEAN signed a Free Trade Agreement and a related Investment Agreement. The agreements will enhance legal certainty, investment protection and market access for the trade of goods and services, which will create new business opportunities and boost trade and investment between Hong Kong and ASEAN.

3. Integration with the Greater Bay Area

Hong Kong’s positioning within the Greater Bay Area (GBA) strengthens its status as a platform for BRI investment. Key elements include:

- SOE concentration: Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are expected to play a highly active role in the BRI, with many using the GBA as their national and international headquarters.

- Transport and logistics: The GBA is home to a world-class transport and logistics network that is continually expanding and will provide significant support to BRI investors with their trade requirements.

- Innovation and technology: There are plans to expand the GBA’s positioning as a regional technology hub. An example of this is the agreement between Hong Kong and Shenzhen to develop the Lok Ma Chau Loop into one of the world’s largest innovation and technology parks on the border of the two cities. For countries and companies participating in the BRI, leveraging innovation and technology in the GBA will support the acceleration of their economic growth and development.

4. Professional services community

Hong Kong has more than 250,000 professionals working in the financial services sector. In addition, its professional services workforce numbers more than 217,000 in areas such as legal, accounting and auditing, architecture and engineering, information technology, advertising and specialised design.

Hong Kong’s professional services community has in-depth experience working with international investors, lenders and public sector entities on their inbound and outbound work, underscoring the city’s leading role in facilitating trade and investment both locally and along the Belt and Road.

5. Cultural diversity and human capital

The Hong Kong workforce represents a deep and diverse talent pool of resources with skills, multilingual capabilities and international experience suitable for companies seeking to be active in the BRI.

Female labour force participation in Hong Kong also continues to increase significantly, while there is a growing working population from diverse backgrounds and nationalities spanning Europe, North America and other parts of Asia Pacific.

The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (Hong Kong Government), through enhancement measures to its immigration policy, continues to look at ways to recruit top talent from outside Hong Kong. It also continues to offer financial incentives to individuals who pursue continuing education and training courses in order to broaden the knowledge and capabilities of the city’s workforce and wider community.

Please click to read full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Thomas So, President, The Law Society of Hong Kong

In December 2017, the Hong Kong SAR Government signed an Arrangement (the ‘Arrangement’) with the National Development and Reform Commission for Advancing Hong Kong’s Full Participation in and Contribution to the Belt and Road Initiative (the ‘Initiative’).

The Arrangement highlights Hong Kong’s unique strengths in specific key areas and maps out Hong Kong’s role in the long term development of the Initiative. Twenty six provisions detailing the support and cooperation opportunities to be provided by China’s Central Government to Hong Kong in the areas of finance and investment, infrastructure and maritime services, economic and trade, and dispute resolution are set out in the Arrangement.

Equipped with the necessary talent and expertise, Hong Kong has secured an important role in the Initiative. Hong Kong is to serve as a super platform to facilitate, for instance, cross border regulated investment activities, the financing of infrastructure projects and the management of their implementation including consultation, project supervision, maintenance, insurance and environmental protection aspects. Enterprises in the Mainland are encouraged to set up their regional headquarters in Hong Kong and to use Hong Kong as a platform to go global in partnership with Hong Kong enterprises. Provisions on the further opening up of the Mainland market to Hong Kong and enhancements of CEPA are included. The Arrangement also supports Hong Kong to play an active role in driving the development of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Bay Area and to act as a two-way open platform to facilitate respectively international and Mainland investors to go in and out of the Bay Area cities. The Arrangement has affirmed Hong Kong’s status as a global hub for offshore Renminbi businesses, for maritime and aviation services as well as for dispute resolution services.

The Arrangement sets the direction for Hong Kong’s future involvement in this visionary Initiative which will impact generations in many years to come. As the development progresses, the demand for professional services will increase. Our profession must be well prepared to grasp the opportunities when they arise.

It has however been noted that the HKSAR Government’s approach is often narrowly focused on the dispute resolution capability of the legal profession. Its promotional activities are heavily geared towards arbitration services. However, in addition to arbitration, the services that solicitors in Hong Kong can provide cover a wide range relating to capital markets, banking and finance, mergers and acquisitions, real estate and construction, insurance, shipping and many others. The key measures identified in the Arrangement demonstrate that legal services support will be in great demand in many of these practice areas.

Whenever a suitable opportunity arises, the Law Society promotes the availability of a full range of legal services in Hong Kong to the international community. Further, taking into account that the projects arising from the Initiative will mostly be cross-jurisdictional, the Law Society will be introducing more training courses on cross-border transactions to equip our practitioners with the necessary skills.

In addition, the Law Society has been leading efforts to strengthen our Hong Kong brand as a world class legal service provider. This encompasses work on various fronts, including maintaining professional standards through relevant and effective training for our members and sharing our professional legal training with other jurisdictions.

The Initiative has brought immense opportunities for an expansion of the legal services market to various emerging economies. The Law Society has been coordinating efforts in opening up these emerging markets and promoting the quality services Hong Kong solicitors can offer to them. On 12 May 2017, the Law Society held our Inaugural Belt and Road Conference (‘the Conference’) attracting over 650 participants. The Conference created a platform for our members to showcase their capabilities and to connect with potential business partners from overseas jurisdictions. During the Conference, 39 law associations from 24 jurisdictions signed a “Hong Kong Manifesto” uniting efforts to advance the legal profession’s interests and to capitalize on the business opportunities arising from the Initiative.

This year, the Law Society will organise its second Belt and Road Conference on 28 September. The theme will be on “A, B, C” - Artificial intelligence, Blockchain and Cloud. The wave of technology has overwhelmed the world to an extent that the legal and ethical requirements are at the risk of being neglected to give way to technological innovations. Our 2018 Conference will focus on the legal and ethical challenges in building a smart Belt and Road. As in last year’s Conference, the Law Society will extend invitations to our overseas counterparts along the Belt and Road to join the 2018 Conference. It will be an excellent opportunity for members to reach out, build their connections and exchange professionally with a broader network. More details about the 2018 Conference will be announced in due course, but for those interested, please mark your diary first.

Please click to read the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Concerns over China's geopolitical intentions remain a challenge for Belt and Road projects in Southeast Asia.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has not moved quite as quickly in Southeast Asia as it has in South or Central Asia. This is partly down to ongoing tensions in the South China Sea, which have raised concerns among some countries in the region as to China's geopolitical intentions.

At present, the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is caught between these concerns and a desire to enhance its already strong trade relations with China. Overall, there is a recognition that the region would benefit from BRI-driven investment, with the Asian Development Bank maintaining US$1 trillion needs to be spent on infrastructure development by 2020 just to maintain current growth levels.

Xue Li is the Director of International Strategy at the Beijing-based Chinese Academy of Social Sciences' Institute of World Economics and Politics. Outlining the challenge facing the BRI, he said: "We haven't done enough to attract countries in Southeast Asia. On the contrary, their level of fear and worry toward China seems to be rising."

For Southeast Asia, the Singapore-Kumming Rail Link is something of a test case. This high-speed link will run through Laos, Thailand, and Malaysia, before terminating in Singapore, a total distance of more than 3,000km. To date, though, not everything is going the way China might have preferred.

In Laos, construction has been delayed. It is also likely that all of the work will have to be paid for by China, as Laos cannot afford the $7 billion required. In Thailand, meanwhile, negotiations have broken down. The Thais now want to build only part of the line – short of the border with Laos – and finance it themselves without Chinese involvement.

As to which company will build the Singapore-Malaysia stretch, that will be decided next year, with Chinese – as well as Japanese – firms emerging as the current frontrunners. Across the board, though, there is unhappiness at what is considered excessive demands and unfavorable financing conditions on the part of the Chinese. Back in 2014, Myanmar pulled out of the project, citing local concerns over the likely impact of the project.

A similar situation has now arisen in Indonesia. The $5.1 billion Jakarta-Bandung High-speed Railway Project, seen as an early success for the BRI, may now require significantly more funding. Indonesia is also unhappy at what it terms 'incursions' into its waters by Chinese fishing boats. It is, however, trying to downplay their significance as a 'maritime resource dispute' in a bid not to deter Chinese investment in the country. The Philippines is, by comparison, less conciliatory, largely because China is not one of its key trading partners. At present, the Philippines and Vietnam are the ASEAN nations most cynical with regards the ultimate intentions behind the BRI.

Singapore, a country with no direct stake in the South China Sea, remains strongly committed to the Initiative. In March this year, Chan Chun Sing, Minister in Prime Minister's Office, emphasised the importance of BRI as a means of improving links with China and its near neighbours.

He said: "The BRI represents a tremendous opportunity for businesses in Singapore – as well as in the wider Southeast Asian region – to work more closely with China. The more integrated China is with the region and the rest of the world, the greater the stake it will have in the success of the region. The more we are able to work together, the more it will bode well for the region and the global economy."

In line with this, this year has seen a number of Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) signed between China and Singapore. Back in April, one such undertaking was signed between International Enterprise Singapore (IES) and the state-owned China Construction Bank. Under the terms of the memorandum, $30 billion is now available to companies from both countries involved with BRI projects. At present, the two organisations are in discussion with some 30 companies with regards to developments in the infrastructure and telecommunications sectors.

In June, an additional MOU was signed between IES and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China. This has seen a further $90 billion earmarked to support Singapore companies engaged in BRI-related projects.

Ronald Hee, Special Correspondent, Singapore

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Knight Frank

“Over the last two generations, we have seen a familiar trend of rising wealth and influence in Asia. It started with the Japanese in the 70s and was followed by the Koreans in 90s and the South East Asian “Tigers” in the early 2000s. For the past decade, China and India have been among the powerhouses of world economic growth. Given their ambitions and scale, they are both likely to be important contributors for a very long time,” says Kevin Coppel, Asia Pacific Regional Head at Knight Frank.

Coppel adds that the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is one of clearest manifestations of China’s vision and influence – the infrastructure and investment underpinning the BRI will streamline trade flows and lift economic activity in much of Asia, the Middle East, and North and Eastern Africa. While the vision will bring huge opportunities for investors and developers, the BRI will also change the face of corporate China, which will have an enormous influence in the 21st century as Chinese brands become household names around the world.

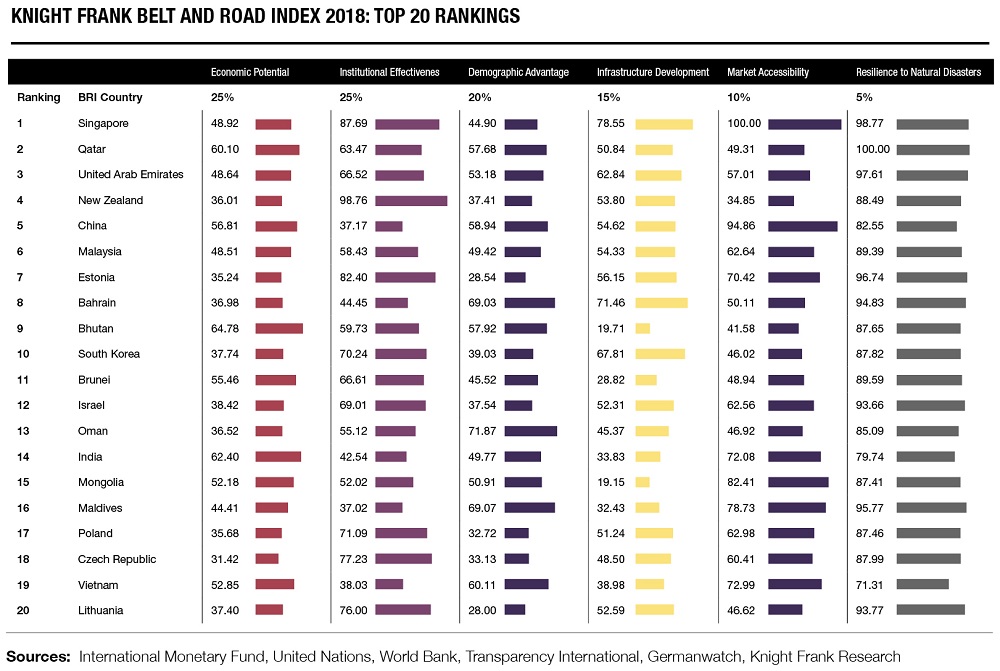

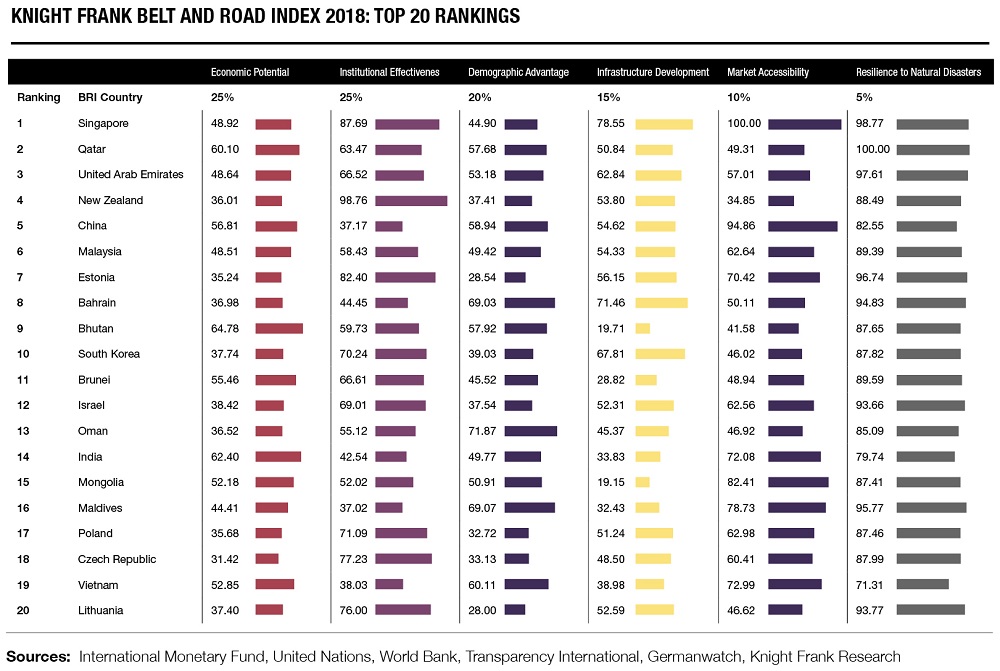

In order to help investors better understand the potential opportunities that the BRI could generate beyond their borders, Knight Frank has developed its inaugural Belt and Road report titled New Frontiers: The 2018 Report. It features the Belt and Road Index which assesses 67 countries considered core to China’s initiative.

Highlights of Belt and Road Index 2018:

- Singapore, Qatar and United Arab Emirates top the Index.

- Southeast Asian countries rank favourably, especially Malaysia and Vietnam. Apart from Singapore, many Southeast Asian countries are confronted with major infrastructure financing deficits. Chinese companies are well-placed to plug those gaps.

- Middle Eastern countries diverge in their rankings, reflecting the potential and challenges that co-exist in the region. While Qatar, UAE, Bahrain, Oman and Saudi Arabia are in the top half, Iraq and Yemen sit in the bottom half.

The index is classified into six categories: economic potential, demographic advantage, infrastructure development, institutional effectiveness, market accessibility and resilience to natural disasters. Values for these six categories have been normalised from the various data sources and are assigned specific weightage that commensurate with their perceived importance to investment decisions.

Top recipients of Chinese outbound real estate investment

The report also highlights the flow of Chinese outbound investment in real estate along the BRI.

Over the last four years notably along the BRI, Singapore (US$3.87 bn), Malaysia (US$2.37 bn) and South Korea (US$2.74 bn) are the top recipients of Chinese outbound real estate investment which totalled US$10.2 billion. Slightly over half of this total amount (US$5.2 bn) was spent on purchasing development sites, while another third (US$3.1 bn) was spent on office space.

Nicholas Holt, Asia Pacific Head of Research at Knight Frank, explains, “The Belt and Road Initiative is a long-term strategy that will play out over decades, not simply years. Therefore, it will take patient capital that is prepared to look at new frontier markets with greater levels of country risk and at greenfield projects that have a long-term time horizon. For many, this transition away from pure-play, low-risk investment, requires detailed market knowledge and advice in terms of deal sourcing, evaluation, execution and asset management.”

Please click to read the full report on the Knight Frank blog page.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

香港中文大學藍饒富暨藍凱麗經濟學講座教授劉遵義

摘要

粵港澳大灣區內一共有11個城市——香港、澳門、廣州、深圳、珠海、佛山、中山、東莞、肇慶、惠州和江門。2016年大灣區的總人口為6千8百萬,總境內生產總值 (GDP) 為1.39萬億美元,而人均GDP為20,412美元。英國現時為全球第五大經濟體,人口與大灣區相若,而GDP則差不多兩倍於大灣區。以大灣區經濟現時增長的速度,十年最少可以翻一番,大灣區經濟規模在十年後應可超越英國,成為全球第五大經濟體!

大灣區內城市各有所長,應當邁向經濟一體化,才能高效利用它各個城市的資源,充分發揮它們的潛力和經濟互補性,實現規模報酬,協調各城市各自專門化、分工協作與有序發展,避免重複建設與惡性競爭,構造正和與多贏局面。要組合大灣區的經濟,應當考慮在區內成立試點自由貿易區,先行先試。經濟要一體化,就必須做到在大灣區內四通。就是:貨物與服務流通、人員流通、資金流通與資訊流通。大灣區內的基礎建設,應當都可以相互共用。港深齊心協力合作,可以打造粵港澳大灣區成為全球創新、創投與融資中心。大灣區最終可成為一個超巨型的國際大都會,而屆時人均GDP也會超過4萬美元,進入發展經濟體行列!

1.引言

粵港澳大灣區內一共有11個城市——香港、澳門、廣州、深圳、珠海、佛山、中山、東莞、肇慶、惠州和江門。2016年大灣區的總人口為6千8百萬,總境內生產總值 (GDP) 為1.39萬億美元,而人均GDP為20,412美元。現時大家都很關心中國能否脫離中等收入陷阱,其實大灣區早已經超過中等收入經濟體的門檻了。粵港澳大灣區內11個城市各有所長,但需要協調,多元分工與有序發展,避免重複建設與惡性競爭。大灣區的總和大於其所有部分的總和。這不是零和遊戲,一定可以做到正和與多贏!

香港基本上已經沒有製造業,尤其是高科技製造業,但擁有世界級的研究型大學,可以為大灣區培養科技、工程與醫療人才以及供應研發服務,尤其是基礎研究。香港亦有強大與國際化的金融業,可以支援其它大灣區城市的政府與企業,以發行債券或股票方式,在香港籌集資金發展,以及走出去到海外投資。香港亦有豐富的創意人才,可支持創意產業,例如電影業,在大灣區內發展。

澳門是以博彩業與旅遊業為主,還有會議與展覽業務,但它的經濟需要更多元化。

廣州是廣東省的省會,是政治與經濟中心,有重工業(例如汽車製造業)、輕工業與服務業,也有一流的大學(例如中山大學與華南理工學院),也是廣東省的運輸樞紐。

深圳有非常成功的高科技企業,例如華為、中興、比亞迪與華大基因等等,在研發方面有大量投入,也有蓬勃發展的深圳證券交易所,主要服務民企,但在高等教育與醫療方面,還相對比較不足。

珠海有製造業(例如電子儀器及機械),亦有可加強利用的國際機場。港珠澳大橋通車後,應當有更高速的發展。

佛山是全國出口商品的綜合基地之一,產品包括家用電器、電子、紡織、塑膠、皮革、食品、陶瓷、服裝、印刷、建材、鑄造與機械等,主要以輕工業為主。

中山是消閒中心,港珠澳大橋通車後,也會成為香港與澳門的市郊,適宜港澳市民長期居住。

東莞正在轉型過程中,從中小型輕工業轉為高科技企業的後院,支援大灣區高科技產業的持續發展。中山是消閒中心,港珠澳大橋通車後,也會成為香港與澳門的市郊,適宜港澳市民長期居住。

肇慶是歷史文化名城,也是優秀的旅遊城市,人均GDP現時較低,有大幅度增長的潛力。

惠州有電子製造業與石化工業,還有大量發展的空間。

江門是紡織服裝、化學纖維、食品、皮革與紙制產品主要生產基地之一,可供應大灣區內外市場。

大灣區內這十一個城市之間,除了地理鄰接之外,還有方言、文化、歷史與鄉土、血緣的關係,同時它們的經濟互補性大於經濟競爭性,應當比較容易協調合作,創造多贏。

2.願景

2016年粵港澳大灣區11個城市的總人口為6千8百萬,總境內生產總值為1.39萬億美元,而人均GDP為20,412美元。英國現時(2016年)為全球第五大經濟體,人口為6千5百1十萬,境內生產總值為2.63萬億美元,而人均GDP為40,399美元。英國人口與大灣區相若,而GDP則差不多兩倍於大灣區。以大灣區經濟現時增長的速度,十年最少可以翻一番,而英國經濟增長相對緩慢,在加上脫歐影響,大灣區到2027年就可以趕過英國,成為全球第五大經濟體!而大灣區人均GDP也會超過4萬美元,進入發展經濟體行列!大灣區最終會成為一個超巨型的國際大都會。

3.大灣區的機遇與挑戰

粵港澳大灣區的總和應可大於其所有部分的總和。大灣區應當邁向經濟一體化,才能高效利用它各個城市的資源,充分發揮它們的潛力和經濟互補性,實現規模報酬,構造正和與多贏局面。假使大灣區經濟能一體化,它的增長速度會比現時更高。要組合大灣區的經濟,應當考慮在區內成立試點自由貿易區,先行先試。當然,還有廣東省自己本身的自由貿易區,比大灣區要更大。希望能夠在大灣區裡面先試點成立自由貿易區,再逐漸延伸到整個粵港澳。

經濟要一體化,就必須做到在大灣區內四通。什麼叫四通?就是:貨物與服務流通、人員流通、資金流通與資訊流通。大家都說紐約大灣區、東京大灣區與三藩市大灣區都是粵港澳大灣區的榜樣,但是它們有一個共同點,它們都能做到這四通,沒有限制,這是粵港澳大灣區所缺乏的。大灣區要做到全面四通,不是一朝一夕的事情,除了需要所有十一個城市齊心通力合作外,也需要中央政府的大力領導和支持,才有可能做得成功,但也需要一段比較長的磨合時期(最少五到十年),假如在這段時間內能夠做到四通,就非常不錯了。

4.大灣區經濟一體化——四通:貨物與服務流通、人員流通、資金流通與資訊流通

貨物與服務流通

貨物在大灣區中能夠自由流通,至為重要,若需要重重檢查,則費時失事。這個問題可以通過建立大灣區試點自由貿易區,引進高科技的辦法來解決,讓在大灣區內生產的商品,在區內可以全免關稅、自由流通。準備跨境往來,從港澳到大灣區內其它城市,或從大灣區內其它城市到港澳的商品,可以預先設置 RFID (“Radio Frequency Identification(無線頻率鑒定)”) 標記。RFID是一種可附在商品上的電子標記,可證明原產地,以便於在大灣區內可以自由通行。RFID亦可記載其它資料,例如價格、生產日期、適用時期、商品成分、質素驗證與曾否課稅等等。

港澳地區運到境內大灣區外地區的商品,可在港澳預檢並預付關稅,以RFID標記證明,經保稅密封運輸工具直接送到大灣區外地區。無RFID標記證明已預付關稅之商品,在進入大灣區外境內地區,就必須完稅,這是在高科技時代可以做得到的事情。從境內大灣區外地區運到港澳地區的商品,亦可以經過RFID標記證明,在內地預檢並如有需要預繳法定稅款後,自由進入港澳。

貨物流通做成功之後,可以進一步考慮服務業的流通。在大灣區內每個城市的合格服務業經營者,應可申請到其它城市註冊,提供服務,但需要完全符合其它城市的資格要求,並嚴格遵守其它城市的法律與規章。

人員流通

首先,在大灣區內各內地城市有正式戶籍的居民,都可以向香港或澳門特區政府分別申請港澳通行證,獲得批准之後,可以憑證自由往來港澳,比照現時港澳有永久居住權的中國公民,可以申請通行證,憑證自由往來內地。但這並不包括長期居留,長期居留還需要另行申請。為方便人員流通,也可考慮允許港澳居民在大灣區內各內地城市,成立香港或澳門子弟學校,也允許大灣區各內地城市居民在港澳成立內地子弟學校。現時在內地的台商子弟學校,就是先例。

其次,是資格互認,專業資格可以在大灣區內實行互認,標準可以用大灣區內各城市現行標準之中之最高標準,一旦獲得通過,該專業人員可以在大灣區內所有的城市服務。專業可以包括工程、會計、設計、醫療、看護與法律等等,其中法律可能是最困難的,因為需要同時達到港澳與內地的最高標準。大學學位與其它學歷也都可以按各城市之最高標準互認。

第三,是稅負理順。港澳與大灣區內內地城市永久居民跨境就業時,除了避免雙重課稅之外(但也應避免雙重不課稅),其它與就業有關的負擔,例如“強積金”與“四險一金”,可以按該僱員之永久居留地辦法處理,這樣就比較簡單化。(例如香港永久居民在境內大灣區任職,其內地僱主可為該僱員向香港強積金供款,而不需要供內地的四險一金。內地大灣區永久居民在港澳任職時,僱主亦可為該僱員向其永久居留地付需要的四險一金,而不須付港澳的強積金或退休金或其它不是必須的保險。)在大灣區內各城市有正式戶籍的學術與研究人員,跨境在大灣區其它城市工作時,可以豁免當地(包括中央政府與港澳)個人所得稅三年,只需繳付永久居留地的個人所得稅,以鼓勵大灣區內學術與研究人員交流、促進合作創新。中央政府與澳門特區政府之間已有此協議。在中央政府與香港特區政府之間尚未達成協議之前,可能需要大灣區地方政府暫時補貼。

第四,假如大灣區人員跨境流通需要暢順,就必須實行“一地兩檢”。一地兩檢,甚至一地多檢,不乏世界先例:從加拿大去美國,是在加拿大先驗證;從瑞士到法國,從歐洲大陸坐特快車 (Eurostar) 到倫敦,也是一地兩檢。現時假如從香港乘車經深圳灣到深圳,過境時就是實行一地兩檢,香港的進出口關卡就設在深圳那邊。假如不推行一地兩檢,所有連接大灣區的跨境基建工程,成效會大打折扣,也是資源的浪費。期望“一地兩檢”能早日落實。

其實,“一地兩檢”的主要受惠者是香港居民。在“一地兩檢”之下,香港居民乘高鐵可直接來往內地各大城市,不必在中途下車受檢;不然的話,香港需要派遣官員,分駐內地各大城市高鐵車站,預先檢查高鐵乘客之後,乘客才能上直通車赴港。另外也方便內地各大城市訪港旅客,無論是商務或旅遊,鼓勵他們多來香港,促進香港經濟持續繁榮。

此外,在港珠澳大橋建成通車之後,可以考慮“三地車”的安排。已有粵港兩地牌的汽車,如有需要,可向澳門特區政府申請在澳門行駛的牌照。已有粵澳兩地牌的汽車,如有需要,亦可向香港特區政府申請在香港行駛的牌照。假如有需要控制跨境車輛流量,可以利用跨境牌照費來調整,讓最有需要在粵港澳三地往來的車輛(例如大型公共汽車),能優先獲得三地牌,也可考慮引進臨時三地牌,只能在短時期內作一次往來使用。

資金流通

在大灣區內,應當全面實行國民待遇。跨城市投資與在本城市投資,只要合法,都一視同仁。資金在大灣區內,無論是人民幣、港幣、澳門幣、美元、歐元或是其他貨幣,除了牽涉到資本帳戶下資金從境內非大灣區進出大灣區時,均可隨時自由流動,經常帳戶下資金流動更是完全沒有限制。

資本帳戶下資金從境內非大灣區進入大灣區內內地城市時,不受限制,但要轉到境外,就必須先存放在商業銀行戶口裡一年以上,並需經核准後方可。就是說:在境內大灣區外的資金,轉到大灣區裡面,要存放一年以上,才能夠繼續轉到境外。這是一個權宜辦法,要不然,就等於全國內地資本帳戶下流出境外變成完全沒有管制了。同樣地,資本帳戶下資金從境外進入境內大灣區內內地城市時,亦不受限制,但要轉到境內非大灣區,也必須存放在商業銀行戶口裡一年以上,並需經核准後,才能再轉到境內非大灣區。現款於銀行入存或提出,超過十萬元人民幣等值,就必須登記日期、數目、來源和去處。這其實主要是倚靠高科技,就是說:每筆銀行存款都有數碼數據注明原始來源地、存入、轉帳和提出的日期。

資訊流通

資訊一致,是經濟效率最優化的重要條件。資訊在大灣區內互聯網上,經過用戶實名登記後,可以考慮開放,因為完全可以追蹤。電視與電台新聞報導(例如天氣預告),在大灣區內,經過實際負責人實名註冊登記後,亦可以考慮開放。其它媒體、書籍與文化產品,經實際負責人實名註冊並志願受檢合格通過後,亦可以考慮開放在大灣區內自由流通。

原文刊載於2017年8月,請按此閱覽全文。