Chinese Mainland

Sitting at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, Middle East and Africa, Turkey has long been regarded as a highly important strategic hub for global trade, logistics and manufacturing. That status has been enhanced by its customs union with the EU and extensive array of free trade agreements (FTAs) with nearly 30 countries, which have given it free or preferential access to a pool of some 900 million consumers.

Coupled with the linking together of the country’s Middle Corridor Initiative (MCI) and China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and a clutch of generous investment incentives, Turkey has become increasingly attractive to Hong Kong companies eager to trade and invest there. This is particularly true for those which are looking for business and relocation opportunities as a hedge against the problems caused by the lingering Sino-US trade spat.

China’s recent import tariff cuts – part of its shift towards a consumption-driven economy – are also creating Turkish-related opportunities for Hong Kong firms. As Turkish traders look to take advantage of the import control relaxations and enter further into the Chinese mainland market, Hong Kong’s service providers will expect to use their extensive knowledge and experience of the market to play a pivotal role in helping them do so.

Regional Connection

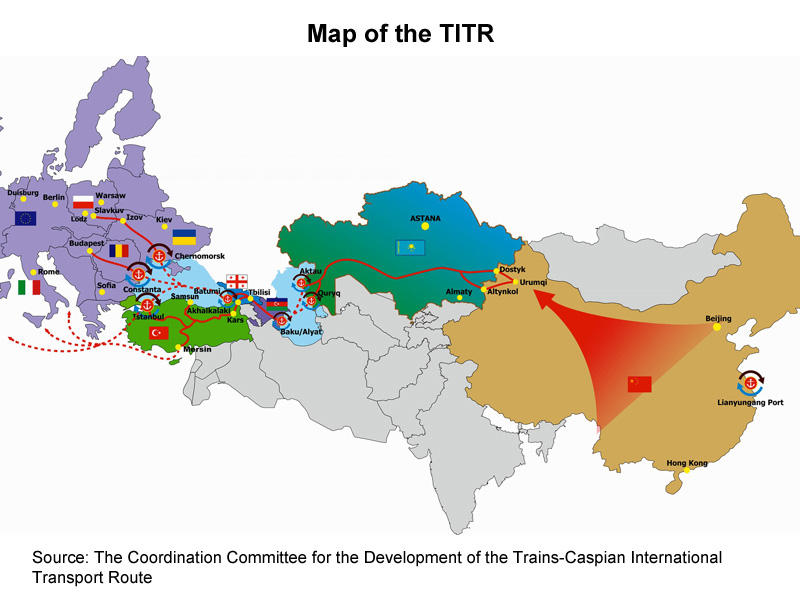

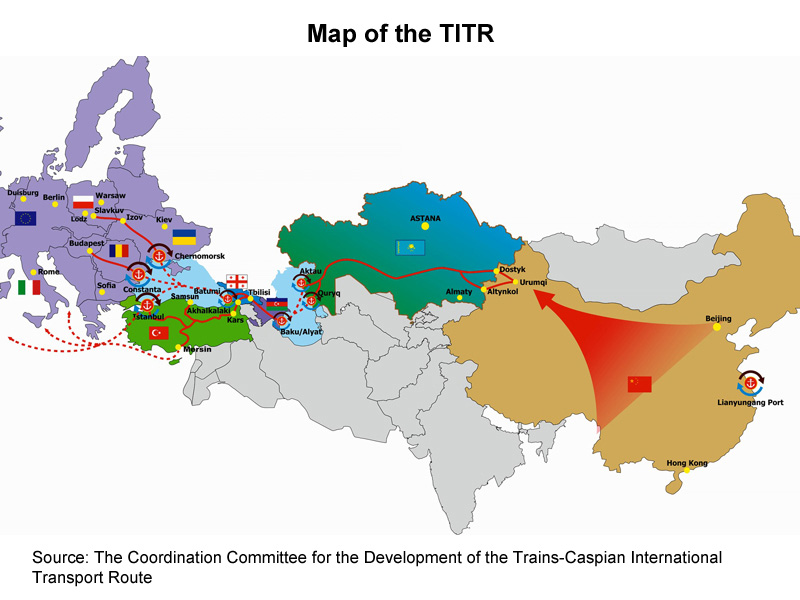

The link-up between Turkey’s MCI and China’s BRI is already bearing fruit. An early example of this is the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR), which forms the shortest land route between China and Europe, via South-east Asia, Central Asia and the Caspian Sea.

At its heart is the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars (BTK) railway route, which opened in October 2017. It starts at the Caspian Sea in Azerbaijan and runs through Georgia and eastern Turkey before merging with the Turkish and European railway systems.

The TITR is not just a shorter land route for Asian products to reach European, African and Middle Eastern consumers, but also a safer and cheaper one. The corridor is 1,500km shorter than the China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor and is less exposed to extreme winter weather conditions. Cargo trains from North-West China now take as little as 8 to 14 days to reach the Black Sea coast and Turkey, whereas sea voyages between the destinations can take up to 60 days.

Turkey has also been upgrading and developing new maritime logistic infrastructure, most notably in İzmir. Dubbed the Pearl of the Aegean, Izmir is the nation’s third most populated city and home to the North Aegean Çandarlı Port, which when completed will rank as one of the top ten seaports in the world. With an additional annual capacity of up to 12 million 20ft shipping containers or TEUs, the port is expected to increase Turkey’s cargo handling capacity by 70%.

Infrastructure Boom

In line with its ambitious vision to develop Turkey into a US$2 trillion economy by 2023, the Turkish government has been overseeing a spending spree on the country’s infrastructure. The aim is to lay a sound foundation for more dynamic economic development. Among the long list of projects is Istanbul’s new airport, which will replace the 93-year-old Ataturk Airport when it opens on 31 December 2018. It is projected to become the busiest air hub in the world with a planned yearly capacity of 200 million passengers – nearly double that of the current world leader, Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport.

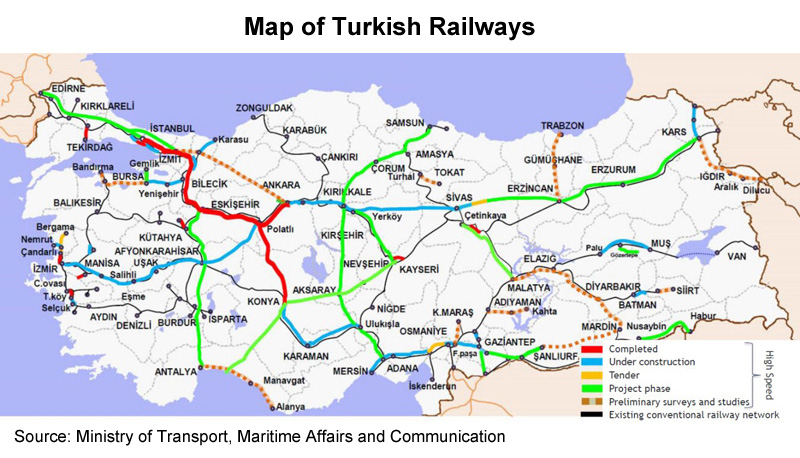

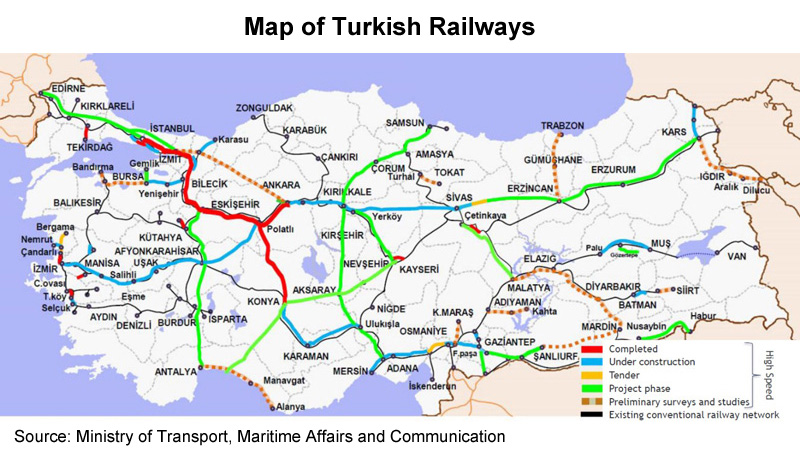

The Turkish government also aims to complete 11,700 km of high-speed railway lines linking 41 domestic cities by 2023, which would put Turkey behind only China in terms of the amount of railway construction. Other key projects among the 3,500 reportedly under development or in the planning stage include the Kanal Istanbul (an alternative waterway to the Bosphorus River, linking the Black Sea with the Marmara Sea), the Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge (the world’s longest, highest and widest suspension bridge with a two-lane railway and eight-lane highway on the same deck), the Eurasia Tunnel, the Istanbul Finance Centre, and the Gebze-Izmir Motorway Project linking Istanbul with Izmir. All this is taking place alongside more than US$200 billion worth of building work and urban renewal across many Turkish cities.

To help finance this, the Turkish government hopes to secure US$350 billion foreign investment on a Public-Private Partnership (PPP) basis. So far, the country has completed a total of 225 PPP projects worth some US$135 billion. These include the İstanbul New Airport, built by the Limak-Kolin-Cengiz-MaPa-Kalyon Consortium, the Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge and Northern Marmara Highway by the IC İÇTAŞ – Astaldi Consortium ICA and the Eurasia Tunnel by the Turkish-Korean joint venture registered as Eurasian Tunnel Operation Construction and Investment, or ATAŞ.

Manufacturing Powerhouse

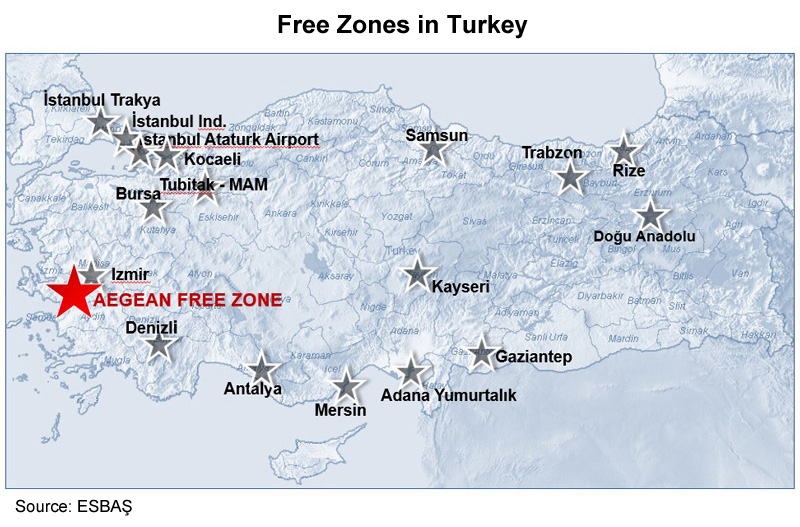

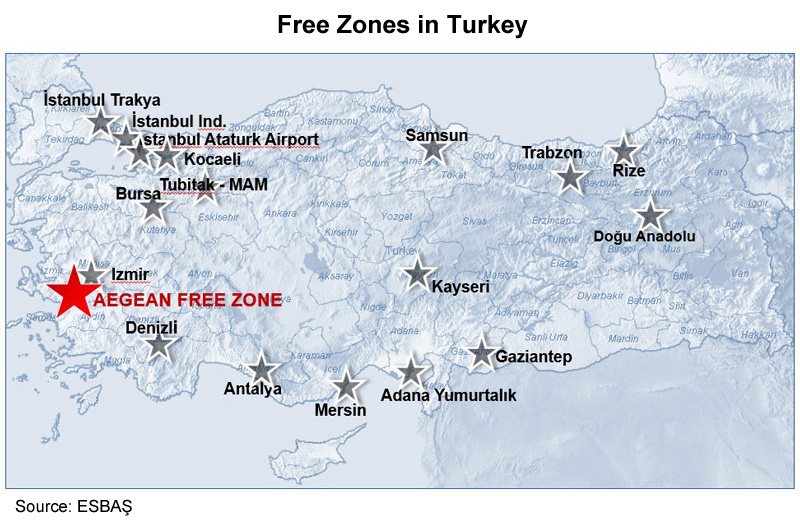

Turkey’s growing economy and its rapidly improving transport connections have made the country attractive to international manufacturers looking to relocate. In order to ride this wave, the Turkish government has been trying to entice foreign export-oriented companies to move their production to the nation’s 19 Free Zones, 322 Organised Industrial Zones and 56 Technology Development Zones (TDZs).

The Aegean Free Zone (ESBAŞ) in İzmir, with its advantageous location and tax, legal and customs incentives, is becoming increasingly popular as a destination for international manufacturers looking to do business in Turkey and the surrounding region. ESBAŞ is home to nearly 180 investors and tenants, mainly in industries such as food processing and packaging, automotive, machinery, IT, medical devices, textiles, electronics and electrical, aviation, avionics and aerospace. These include world-class manufacturers such as US-based Delphi Diesel, which makes injector nozzles, valves and pump parts for diesel motors, France’s FTB Lisi Aerospace, luxury German fashion house Hugo Boss, Eldor Electronics from Italy, Ukrainian manufacturer DEZEGA, which specialises in respiratory protective equipment, and Lasinoch, a subsidiary of Japan’s Pigeon Corporation which produces breast milk feeding pumps, feeding bottles and pacifiers.

Sino-Turkish Co-operation

As a key part of the ancient Silk Road, Turkey is naturally an important partner in today’s Silk Road Economic Belt and Maritime Silk Road, or the BRI. Even before the development of the BRI, there had been a growing collaboration between Turkey and China. In 2010, China was a strategic partner in the financing and construction of Turkey’s national high-speed railway between the cities of Edirne and Kars, providing loans of US$28 billion, while the China Railway Construction Corporation and China National Machinery Import and Export Corporation are members of a Turkish-Chinese consortium (along with Turkey’s Cengiz Construction and Ibrahim Cecen Ictas Construction) which was behind the construction of the İstanbul-Ankara high-speed Railway.

The İstanbul-Ankara High-speed Railway

In 2015, the Chinese joint venture Euro-Asia Oceangate, controlled by Cosco Pacific, China Merchants Holdings (International) (CMHI) and CIC Capital, acquired the majority share of Kumport, the third-largest container terminal in Turkey. The port is close to İstanbul, Turkey’s biggest city and its key trading hub which accounts for over half of the nation’s total trade and serves as a transhipment hub for goods being transported via the Black and Mediterranean Seas. This investment also creates a natural synergy with the Chinese shipper’s investment and expansion plans in Piraeus – Greece's largest port.

This growing Sino-Turkish collaboration should ensure better co-ordination among the connecting nodes of the TITR and the Maritime Silk Road, while further strengthening the position of Turkey and its surrounding region as Asia’s maritime gateway to Central and Eastern Europe (CEE).

Investment Incentives

On the way to the 100th Anniversary of the Republic[1], Turkey is expected to continue its plans to develop and upgrade its infrastructure and – to make good use of the improved logistics and strengthen its role as a regional manufacturing powerhouse – expand its network of industrial parks in an attempt to grow local production capacity alongside rising domestic and external demand. This is good news for Hong Kong manufacturers who are considering relocation amid the fallout from the Sino-US trade dispute.

Turkey’s keenness to attract foreign investment means that it now boasts one of the most competitive investment incentive packages of any emerging economy. This includes a Project-Based Incentive Scheme, under which projects involving at least US$100 million worth of investment that ensure sufficient supply levels of strategic goods and services, and boost technological capacity, research and development (R&D) efforts, competitiveness and added value in production, qualify for a pool of support measures that the investor can use to create whatever incentive package to make the investment most feasible and profitable.

A host of different schemes offering various support measures are available to suit investment size, region, sector and product. Measures include value-added tax (VAT) exemption, customs duty exemption, tax deductions, social security premium support for the employer’s share, interest rate support, land allocation and VAT refunds. For investments in the least developed regions of Turkey, income tax withholding support and social security premium support for the employee’s share are also available.

Hong Kong businesses looking to take advantages of these opportunities should also be helped by the presence in Turkey of major Chinese banks such as Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), which has been operating there since May 2015, and Bank of China (BOC), which received its banking licence on 1 December 2017.

Turkey Trade

Hong Kong’s trade with Turkey is rising rapidly. In the first nine months of 2018, Hong Kong’s sales to Turkey grew by 15% year-on-year to US$775 million, which compares favourably with the 9% growth in Hong Kong’s total exports over the same period. Electronics and electrical goods such as telecommunication equipment and parts, computers, electrical apparatus for electrical circuits and semi-conductors, electronic valves and tubes, watches and clocks, toys, games and sporting goods, jewellery and pearls, precious and semi-precious stones are selling well in Turkey.

When it comes to Turkey’s exports, the country is becoming a leading global supplier in the field of agribusiness and is now the world’s seventh-largest agricultural producer. In 2017, Turkey sold more than 75% of the world’s total market of hazelnuts and exported nuts, figs and olive oil to as many as 140 countries. Other popular food and beverage products include high-quality tea, wine, honey, dairy products and seafood.

Turkey is also the world’s fourth largest home textile supplier, famous for its towels, furnishing and curtain fabrics bed linens, and Europe’s leading TV and white good producer, selling, for example, refrigerators to some 160 countries.

Online Potential

Online sales in Turkey make up a relatively low share of total retail sales at just 3.5%. This means that the potential in the online market is there to be tapped by global e-commerce players. Alibaba has already made a move, recently announcing its acquisition of Trendyol (Turkey’s largest online fashion retailer, with 90 million monthly visits and 16 million registered users) from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and several US investment funds. It hopes to expand and optimise its reach among the country’s growing pool of young, high-income, tech-savvy consumers.

There are also plenty of potential opportunities in Turkey for the provision of the sort of professional services and innovative business models at which Hong Kong excels. Given Turkey’s ambitious list of massive infrastructure projects, high demand is expected not only for project funding and financing, but other professional services such as project evaluation and consultancy, engineering, architecture, logistics, information and communication technology (ICT) and marketing.

However, these opportunities are not limited to those available in Turkey. Turkish businesses are especially keen to make inroads into the Chinese mainland market amid China’s recent import tariff cuts, as evidenced by their presence at the inaugural China International Import Expo (CIIE). This was the world's first import-only-themed national-level expo, which kicked off on 5 November 2018 at the National Exhibition and Convention Centre in Shanghai, bringing together more than 3,600 exhibitors and over 400,000 buyers.

Turkey's Showcases at CIIE

Displays of Turkish exports spanning agricultural and food and beverage products to machinery and services received a very warm welcome from Chinese buyers at the expo. However, while Turkish exporters and service providers seemed convinced that the Chinese market was ready for their products, most admitted that they were unfamiliar with mainland China’s laws and regulations, not to mention the market dynamics in terms of consumer preferences and distribution channels.

Given their language advantages, their extensive knowledge of the Chinese market and regulatory environment and their proximity to the mainland market, Hong Kong companies can play a pivotal role in helping prospective Turkish companies bring their products to the Chinese mainland market.

Hong Kong can also serve as a tailor-made business hub for Turkish enterprises looking to establish headquarters in Asia, offering them an extensive web of the value-added services from finance to branding and research and development (R&D) they will need.

[1] Turkey will celebrate the 100th anniversary of the foundation of the Republic in 2023.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

With funding for phase one finally agreed, the development of the Kyaukphyu Port no longer seems remote prospect.

After two long years of negotiations, one of the key Myanmar Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects reached a significant approval milestone early last month. This saw CITIC, the Beijing-headquartered investment group, commit to underwriting the US$1.3 billion cost of developing phase one of the Kyaukphyu Deep-Sea Port project.

The deal, agreed with representatives of the Kyaukphyu SEZ Management Committee (KSMC), represents a major leap forward in terms of clearing the way for work to begin on the port, a vital component of the BRI, China's ambitious infrastructure development and trade facilitation programme. Perhaps just as significantly for CITIC, it also marks the company's first substantial venture into China's relatively undeveloped neighbour.

One completed, the Kyaukphyu Deep-Water Port, set in the western coastal state of Rakhine, will join Pakistan's Gwadar, Bangladesh's Chittagong and Sri Lanka's Hambantota as one of the region's four primary, BRI-backed marine cargo-handling facilities. Its geographical advantages see it ideally positioned to connect to western China, while it could also function as an effective interchange hub for goods in transit to and from Bangladesh, India, the Middle East and East Africa.

In another plus, it will substantially cut the volume of shipping obliged to round the Malay Peninsula in order to service China's Southern and Eastern ports via the South China Sea. With China already operating two oil and gas pipelines between Kyaukphyu and Kunming, the capital of the southwestern Yunnan Province, the logistical significance of the new facility is more than apparent.

From Myanmar's point of view, the port should prove to be a further boon to its already booming economy. With its year-on-year growth expected to hit 6.8% for 2018, the country – albeit from a relatively low base – is now home to one of the fastest-expanding economies in Asia. Even before it comes on line, the port is expected to make a considerable contribution to the country's ongoing success story, with 100,000 new local jobs in the offing, while CITIC has also promised that 90% of managerial roles will be filled by Myanmarese staff.

Given the clear win-win nature of the project, it is perhaps surprising that it has taken so long to come to fruition. In truth, though, it is a proposal that has been dogged with problems, with a number of them yet to be resolved.

To date, the most obvious issue has been cost. As originally envisioned, the total bill for redeveloping the site would be somewhere in the region of $7.5 billion, a figure that the would-be Chinese investors understandably baulked at. To circumvent this particularly thorny problem, the project has now been broken down into four more easily-fundable chunks.

Similarly, rather than committing to develop the whole site simultaneously, a more sequential approach has been agreed. This will see one, somewhat scaled-down, terminal completed first, while plans for two further terminals – on Made and Ramree, two nearby islands – have been put on indefinite hold.

Aside from budgets, the other hugely-divisive issue was ownership. As originally envisaged, CITIC would have had an 85% stake in the completed project, with only the remaining 15% state owned. A subsequent change of government saw it politically expedient for CITIC to cut its expected stake to 70%. This will give the Myanmar government the facility to sell on 15% of the project to local, privately owned businesses – some 50 of which are said to have already expressed an interest – while still retaining 15%.

Despite the progress made on both of these former sticking points, there are still a number of contractual issues that need to be resolved before CITIC breaks ground. The issues relate both to the port proper and to the adjacent industrial park that forms part of the overall development scheme. In each instance, separate investment, shareholder and leasing agreements need to be signed, while the port also requires a mutually acceptable concession agreement putting in place. Given the structure of the deal, nothing can be finalised until everything is finalised, meaning it may be a while before the first Chinese supertanker drops anchor in Kyaukphyu.

Geoff de Freitas, Special Correspondent, Naypyidaw

Editor's picks

Trending articles

China-backed SEZ set to transform transport and manufacturing ties between China, Laos, Thailand and Myanmar.

Late last month, the Thai government announced plans to develop a cross-border Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in the Chiang Khong district of Chiang Rai, the country's northern-most province. Once established, it is believed that the new SEZ will act as a nexus for a number of Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) related projects under way in the country, as well as in neighbouring Laos and Myanmar.

More specifically, the SEZ will connect with the existing Mohan-Boten Economic Cooperation Zone (MBECZ), which straddles the Laos-China border. Ultimately, it is anticipated that the zone will act as a hub for the growing economic interconnectedness between Thailand, Myanmar, Laos and China.

Laos' own economic zone development programme has met with considerable success to date and the MBECZ is proving to be no exception. A recent update from the Ministry of Planning and Investment showed that the country's 12 SEZs were already home to 350 Lao and overseas companies, representing total registered capital of US$8 billion, with $1.6 billion of that having already been actively invested.

At present, the SEZ programme has created 14,699 jobs, with 7,564 of these going to local workers. That number is expected to rise imminently following the announcement that a further 40 companies are to set-up within the Boten Specific Economic Zone, which forms part of the MBECZ's core offering.

The Mohan-Boten project, a joint venture between China and Laos, was established in September 2015 at a cost of about $500 million with a remit to focus on agriculture, biotechnology, logistics and cultural tourism. The site was originally developed by the Yunnan Haicheng Group and the Hong Kong Fuxing Tourism and Entertainment Group.

In addition to Mohan-Boten, there are a further two large-scale China-backed clusters in Laos – the Vientiane Saysettha Development Zone and the Vientiane Thatluang Lake Specific Economic Project. The MBECZ, though, has a unique significance in that it interconnects with the border crossing point of the China-Laos Railway, a major BRI project that will ultimately provide the backbone for high-speed train connectivity throughout much of Southeast Asia.

As a consequence, the MBECZ's international trade and finance areas have already attracted investment from many of the companies that are engaged in infrastructure construction activities throughout the country, as well as those actively working on the development of the country's hydropower facilities. It is, however, those businesses that are directly involved with the roll-out of the China-Laos rail link that are most widely represented.

Given the size and prominence of these businesses, it is perhaps reassuring that work on the rail link seems to be proceeding with few notable hindrances. As of March this year, the project was said to be already more than 25% complete and well on course for its officially scheduled 2021 completion date.

Since then, a number of other major project landmarks have been passed, including the completion of the construction work on a 1 km tunnel – the line's longest subterranean stretch – at the end of October. On top of that, the primary construction work on the 7.5 km Nam Khone Bridge – the widest-spanning structure along the course of the route – has also been completed.

In a sign of further progress, October saw China begin to export petroleum products to Laos via the Mohan-Boten border crossing for the first time. Amid much official fanfare, PetroChina delivered 64 tons of diesel to the local importer – the Nationwide Trading Petroleum Public Company – at the China-Laos border. Prior to this first batch arriving, all oil and petroleum shipments to landlocked-Laos had been routed via Vietnam or Thailand.

The opening of this new conduit was given added significance by its clear importance to the future of the recently sanctioned, BRI-backed Laos-China Economic Corridor. Given the numerous construction projects this will entail, demand for fuel across Laos is only set to soar over the coming years.

Geoff de Freitas, Special Correspondent, Vientiane

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Gansu-Islamabad road and rail connection boosts local economy and facilitates rapid transit to upgraded port.

One of the key stretches of the classic Silk Road returned to the forefront of international trade in late October, when the new China-Pakistan road and rail freight link entered active service. Although the project's origins date back to 2005, well before the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – China's ambitious international infrastructure development and trade facilitation programme – was unveiled to the world, the link has latterly been co-opted into the wider scheme, with its success seen as a vital part of the mainland's overall economic masterplan.

As it stands, the new 4,500 km road and rail link sees regular train services connecting Lanzhou, the capital of China's north-western Gansu province, with the city of Kashgar, one of the key trade conduits in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region. From here, freight can travel onwards to Islamabad, the capital of Pakistan, via the largely restored Karakoram highway. Ultimately, the route will extend to the Port of Gwadar, the cornerstone of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and a major BRI project in its own right.

Until now, the transit time for China-origin goods destined for the Pakistani capital and the country's other affluent consumer hubs has been a minimum of four weeks, with sea links accounting for the bulk of such trade. The new land link cuts the travel time by more than 50%, with items expected to reach Pakistani retailers within 13 days of exiting mainland factories.

Inevitably, given this massive logistics upgrade, trade between China and Pakistan is expected to soar. The impact will be all the greater, however, once the planned extensions to the rail link are in place. Eventually, it is anticipated that freight-train services will run directly from Lanzhou to Gwadar, as well as to other ports serving the Arabian Sea. The next phase of the project, however, is still at the planning stage, with work on it not expected to be completed before 2030.

Its final implementation, however, will be truly transformational for the region. All trade between China and Pakistan currently has to pass along the Karakoram highway, a route rendered impassable by the extreme weather conditions prevailing in the country's December-March winter period. Even though this historic route, which wends its way across the Pamir Plateau and the Karakoram Mountains, has been substantially upgraded in the past 20 years, it still functions as something of a bottleneck, a problem that the extended rail link will play a key role in alleviating.

Among the previous upgrades to the existing highway was the US$510 million reconstruction of the 336 km stretch from the Pakistani city of Raikot to Khunjerab by the Chinese border, a move necessitated by cumulative flood damage over an extended period of years. Then, in 2015, construction work was completed on the two large bridges and five kilometres of tunnels that constitute a 24 km section of replacement roadway, which had originally been swept away by the 2010 landslide that led to the formation of the nearby Attabad Lake. With the cost, as with the Raikot-Khunjerab work, underwritten by China, the final bill was said to be in the region of $275 million.

At present, only one section of the highway still has an upgrade pending – the 136 km stretch linking Raikot to Thakot, a relatively small but geographically significant town on the banks of the Indus. Although a $64 million investment deal for the project was agreed with China last year, concern over local financial irregularities has put the backing temporarily on hold.

Even prior to the full implementation of the proposed rail link, the upgraded Karakoram highway is already driving local economic growth. As the primary land conduit between China and Pakistan, it has become an essential link in the supply line that is fuelling the massive BRI-backed infrastructure and power generation projects in the south of the country, many of which are at the heart of the wider $60-billion-plus CPEC initiative.

At the same time, the BRI-backed links have also delivered more tourists to the region, a development bolstered by the opening of the nearby Ruoqiang Loulan airport earlier this year. Close to the Khunjerab border crossing, the new air terminal has also proven to be a shot in the arm to many local towns, notably Tashkurgan, one of the most westerly settlements in China.

Geoff de Freitas, Special Correspondent, Islamabad

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Viking Bohman, coordinator of Stockholm Belt and Road Observatory, and

Christer Ljungwall, affiliated professor in the Asia Research Centre at the Copenhagen Business School

Key points

- The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) provides an opportunity for China to remedy some of its most significant geostrategic vulnerabilities and steer capital-poor countries on to a development path that could transform them into a support structure for the Chinese economy. In the absence of an active response from other parts of the world, this could encourage a more assertive Chinese foreign policy and facilitate China’s attempts to unilaterally shape the future of global economic flows.

- If the European Union (EU) adopts a proactive approach and insists that China respect EU unity and live up to criteria of transparency, sustainability and economic reciprocity, the BRI will provide opportunities for both economic gain and the promotion of democracy and free market models.

- A precondition for such efforts is the development of interdisciplinary European expertise on the BRI. To this end, individual member states, including Sweden, should mobilise and streamline national capacity. As an initial step, we suggest the setting up of a Swedish BRI working group.

One project, many purposes

The main focus of the BRI is to connectAsia and Europe through an extensive web of infrastructure, both “hard” and “soft”. Launched in 2013, the development scheme has come to involve hundreds of billions of US dollars and is now the centrepiece of Chinese foreign policy. Beijing’s principal message thus far has been that the BRI will be beneficial to all – a gift from China to the world. In some ways this is true, especially for developing countries in Asia which are in dire need of infrastructure. Nonetheless, most countries are rightly questioning China’s claim that “win-win” outcomes are the only goal of the project. In reality, the BRI is a way for China to forward its own economic and the political interests, even if this sometimes comes at the expense of its partners.

Out of the economic rationales which underpin the BRI, four stand out as particularly important. The first one concerns overcapacity in the steel and heavy equipment sectors. Since the financial crisis of 2008, after which China introduced an impressive economic stimulus package, investments in infrastructure has saturated the domestic market. This explains the push to create international alternatives under the BRI.

Second, China seeks to access new markets. New BRI infrastructure and the resulting reductions in transaction costs are expected to increase international trade. Many markets along the BRI are already growing quickly and in the long term could significantly benefit Chinese export industries. While underdeveloped countries are unlikely to provide markets for high-end goods any time soon, the EU market, which is the final destination of the BRI, holds great promise for China.

Third, China is attempting to restructure its economy and move away from its traditional investment- and export-led approach to a model in which domestic consumption plays the leading role. This is a painful process, however, and drastic changes in policy can generate unwanted consequences such as temporary spikes in unemployment. In this regard, the BRI serves as a way to continue to rely on the existing investment-export model while slowly restructuring the domestic economy – with the crucial difference that China is now investing abroad instead of in its saturated domestic market.

Fourth, China is struggling with a problem of geographic disparities between western inland provinces and eastern coastal areas. Coastal cities have long benefited from their geographic position and special government treatment, while landlocked regions such as Tibet and Xinjiang have been left out. By stimulating growth on the Eurasian landmass and redirecting economic flows to the west, the BRI could help to compensate western regions for decades of comparatively slow economic development.

Beyond economics, the BRI serves several geostrategic purposes. One crucial longterm impact of the project is that it is likely to reduce China’s vulnerability to coercive economic pressures from the West while increasing Chinese economic leverage over smaller states. The BRI has the potential to achieve this primarily by constructing a more industrially self-sufficient Eurasia and by building land-based trade routes across the continent which can serve as “lifelines” in case of supply disruptions or economic isolation, possibly linked to a trade war, economic sanctions or a conflict in the South China Sea. China’s economic resilience will also be strengthened by efforts to increase international use of the Renminbi (RMB) and to establish financial institutions that operate outside of the Western-led economic system.

These efforts could make China less vulnerable to economic sanctions by creating a type of regional self-sufficiency within a future Chinese sphere of influence. Ultimately, as Western economic deterrent capabilities lose their potency, China will have fewer incentives to abide by those international norms which it perceives as running counter to its interests – the reason being that China could withstand any possible repercussions from the West. In the South and East China Seas, the Chinese military has already shown an increased willingness to push the limits of what is considered acceptable by Western powers and Japan.

The case for engagement

For states that are interested in preventing scenarios in which China becomes more assertive in regional territorial disputes, the objective should be to make sure that China is well integrated into the global economic system and maintains a close, interdependent relationship with the West. This would ensure that Chinese leaders think twice before embarking on controversial geopolitical ventures similar to that of Russia’s incursions into Ukraine. Economic interdependence would ensure that the costs to China of such action, as a result of Western repercussions such as economic sanctions, remain high.

The economic side of the BRI, meanwhile, also has a strategic dimension. As the project unfolds in the coming decades, China’s increased presence in Eurasia will have a significant impact on regional commercial and financial regimes. As China is offering to connect capital-poor countries to the world economy, it can – in the absence of economic alternatives – largely dictate the terms of this process. Countries such as Pakistan and Laos risk becoming heavily indebted and dependent on China, and their markets remodelled to support the Chinese economy. This is likely to increase Beijing’s leverage over these states, not least in allowing it to shape the norms and rules for future economic flows. Although China could in theory use this influence to develop a fair multilateral system, there is evidence from along the BRI to suggest that China will attempt to shape the initiative in a way that maximises its own economic and political advantage, even if to the detriment of others. If liberal democratic countries remain passive, there will be little to counteract and bring to light exploitation and misconduct.

At the same time, it is crucial that the involvement of liberal democratic states does not become a tool for China to legitimise its more dubious activity. China is known to have used economic pressure against smaller states to secure political favours, extract resources and acquire beneficial ownership rights over strategically important infrastructure. Adding to that, corruption is still rampant in China and there are few reasons to believe that such practices will not travel along the BRI. To counteract and avoid becoming complicit in misconduct, the West and its partners need to be clear that they will not support the BRI unless it lives up recognized criteria on transparency, equal say of stakeholders, and environmental and labour standards.

Beijing may be reluctant to accept such demands, but in the coming decades the BRI is likely to hit more than a few bumps in the road. Beyond the sheer unprofitability of many projects, the initiative involves significant risks associated with corruption, environmental degradation and political backlash in host countries. China’s statebacked financial institutions will not be able to sustain unprofitable projects indefinitely – especially when their lending to sustain the domestic economy is approaching its limits.

These troubles are already beginning to impede projects, and there are few reasons to believe that the situation will improve without a change in strategy. As problems grow dire, Chinese leaders are increasingly likely to come to the realisation that the initiative is in need of help from wealthy and respected outsiders to garner financial funds, build institutions and shore up legitimacy among a broad range of stakeholders. In this regard, struggling Chinese projects could provide Europe with an opportunity to influence the course of things. If EU member states manage to establish a joint presence in these areas, they could step in and offer their help to China, with clear demands for increased transparency, sustainability and joint ownership. Even if China refuses, a European presence would help host countries guard against Chinese domination. With credible economic competition, China will have to offer fair deals to developing countries.

Actively participating in the BRI with hopes of influencing China might seem naive, but other options are limited. One alternative approach is to remain passive. This is detrimental because it would facilitate Chinese attempts to unilaterally reshape the economic and political landscape in Eurasia to its benefit. The project is likely to struggle, but given President Xi Jinping’s personal commitment to the project, China’s efforts to shape its neighbourhood would probably continue – albeit at a slower pace.

A second option would be for the West and states such as Japan to become active in BRI areas but on a competitive, rather than cooperative, footing with China. This would have the benefit of making BRI states less vulnerable to Chinese coercion but might lead to heightened geopolitical competition. Economic competition is good, but the creation of two opposing political camps would not be conducive to international cooperation and global interdependence.

A European response

When approaching the BRI, the first concern of the EU should be to safeguard its own unity. In the absence of a common European China policy, additional BRI investment schemes could deepen cracks in EU cohesion by enticing member states to run political errands for Beijing. Greece and Hungary, which have both been promised Chinese economic support, have on several occasions showed their willingness to adapt their policies to China’s liking. Greece most recently refused to sign an EU statement on human rights in China.

Chinese influence in Europe has not gone unnoticed by European leaders. At the 2018 Munich Security Conference, Sigmar Gabriel, Germany’s foreign minister at the time, noted that China, alongside Russia, was “constantly trying to test and undermine the unity of the European Union”. Similarly, Angela Merkel has warned that Chinese economic ties should not come with political strings. While such messages might temporarily strain EU–China relations, they capture the essence of what the EU should be communicating to China: the political positions of EU member states are not for sale.

Additionally, demands should be made that Beijing respect the sovereignty of other states along the BRI which risk falling into a vicious circle of economic dependence on China. Speaking of the BRI, French President Emmanuel Macron has already made clear that “these roads cannot be those of a new hegemony, which would transform those that they cross into vassals”.

Another point of importance in the EU–China relationship is economic reciprocity. China aims to spur economic flows along the BRI but is actively limiting foreign access to its own market. Such policies shield Chinese industries from competition and often deprive other states of trade and investment opportunities in China. The EU Ambassador to China has made clear on several occasions that China is not fulfilling expectations of reciprocity. To continue to insist on this, and possibly make it a condition for EU endorsement of the BRI, would increase the prospects of gaining access to Chinese markets and could serve the EU’s strategic interests by nourishing economic interdependence.

In sum, like-minded EU members states should communicate clear demands on economic reciprocity and respect for EU unity in their relationships with China. These two requirements, in combination with an insistence on the transparency and sustainability of BRI projects, should guide the EU’s approach. To whatever extent possible, efforts should be made to shore up support for this stance among EU member states and other countries along the BRI. Smaller states have an interest in supporting a common stance on China not only because it would guard against Chinese primacy, but also because it is likely to increase chances of making the projects in their countries more successful and distribute the gains more evenly. It is not inconceivable that consensus could be found within the EU for a common approach toward the BRI, especially given that an internal EU report which strongly criticises the BRI recently gained the approval of 27 out of 28 of the EU ambassadors in Beijing.

An opportunity to influence

Observers often emphasise that the BRI will seek to spread Chinese influence by propagating an alternative authoritarian model and by disseminating Chinese values. This is true in many respects, but it is equally true that if the EU can come up with a coordinated response, the BRI provides an opportunity for Europe to spread democratic ideals and market economy models. On the one hand, the EU should not support the BRI unless it is transparent and fair, which in a best-case scenario would lead China to adapt its projects. On the other hand, participating in the BRI will have the benefit of demonstrating that projects designed according to liberal market economic models are more efficient and sustainable. Indeed, projects which lack transparency and joint ownership structures are more likely to be corrupt, face a popular backlash and cause environmental degradation.

In addition, deeper economic integration and people-to-people contacts with China will naturally intensify the Chinese people’s exposure to ideas from the outside world (even Beijing’s sophisticated censorship apparatus has limitations). Many observers have seen the recent authoritarian turn in China as conclusive evidence that economic integration with the West has failed to influence China. Such claims, however, fail to recognise the changes in Chinese society which have taken place since Deng Xiaoping’s reforms were first introduced in 1978. Xi Jinping has ushered in an era of political repression, but this does not necessarily mean that the population is becoming less critical in their thinking. They might very be influenced in a “liberal” direction through their interactions with the West.

A Swedish response

Sweden has clear gains to make from developing a forward-looking strategy for the BRI. The long-term prospects for opening new markets should not be neglected. Nor should opportunities to influence the direction of economic development in Eurasia and other places. The Swedish government is deeply committed to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and has a clear interest in making sure that the BRI meets sustainability criteria. To this end, Sweden could at the EU level push for efforts to mobilise and streamline European development and aid programmes in BRI countries. The combined mass of European projects could then be nudged toward Chinese projects in order to create synergies and cooperation wherever possible. Again, a precondition for such active participation in the BRI should be a common understanding with China regarding environmental standards, transparency, joint ownership and monitoring mechanisms. In such settings, Sweden should leverage its comparative advantage in environmental science and technology to influence projects in a sustainable direction. As of now, however, Sweden, like most other EU member states, lacks the detailed interdisciplinary knowledge that is needed to engage with China in an appropriate fashion. Expertise from disciplines such as environmental science, security studies, political science and development economics needs to be consolidated to create a comprehensive understanding of the BRI. One way to achieve this would be to fund policy relevant research projects and organise interdisciplinary expert groups which would advise the Swedish government on how to approach BRI projects.

To better organise Sweden’s approach, a permanent working group should be established to serve as a knowledge-sharing and coordination platform for ministries, government agencies, civil society organisations and the Swedish business sector. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs would be a natural place to host such a mechanism. This group could also act as a focal point for international exchanges and might serve to organise cooperation within the Nordic region. As a next step, the government should consider institutionalising Sweden's capacity to deal with the BRI through the establishment of an office for Belt and Road issues.

Please click to read full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Paulo Bastos, World Bank Group

Abstract

The Belt and Road Initiative seeks to deepen China's international integration by improving infrastructure and strengthening trade and investment linkages with countries along the old Silk Road, thereby linking it to Europe. This paper uses detailed bilateral trade data for 1995-2015 to assess the degree of exposure of Belt and Road economies to China trade shocks. The econometric results reveal that China's trade growth significantly affected the exports of Belt and Road economies. Between 1995 and 2015, the magnitude of China's demand shocks was larger than that of its competition shocks. However, competition shocks became more important in recent years, and were highly heterogeneous across countries and industries. Building on these findings, the paper documents the current degree of exposure of Belt and Road economies to China trade shocks, and discusses policy options to deal with trade-induced adjustment costs.

Concluding remarks

This paper characterized the dynamics of China’s bilateral trade relationships over the 1995-2015 period and assessed the implications of China trade shocks for exports of B&R economies. Between 1995 and 2015, B&R economies accounted for about a third of China’s export revenue. They have been more important for China as export markets than as sources of Chinese imports (although the share of imports originated in B&R economies has observed upward trend in recent years). China is an important trade partner for many B&R economies, especially as a source of imports. Over this period, exports of B&R economies were significantly impacted by China’s trade shocks. Between 1995 and 2015, the magnitude of China’s demand shocks was larger than that on supply (or competition) shocks, implying that the overall net impact of China trade shocks on the exports of B&R economies during this period was significantly positive. However, the magnitude of competition shocks associated with China’s trade became stronger in 2005-2015. The impacts of China trade shocks were heterogeneous across B&R economies and industries.

Although one must be cautious in extrapolating from historical data, the econometric results suggest that the trade similarity indexes we employed contain useful information for capturing the current degree of exposure of B&R economies to China trade shocks. Looking forward, these measures suggests that several B&R economies currently exhibit a relatively high degree of exposure to competition shocks associated with further integration with China. This is the case of Hong Kong SAR, China, Vietnam, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand and Indonesia, which source a relatively large share of imports from China and have an export structure that is more similar to that of China. These B&R economies are therefore likely to be relatively more exposed to import competition from China in their own markets in several industries. Further integration with China will likely involve stronger competitive pressures in final goods markets, which may also have important implications for the adjustment of factor markets. There are nevertheless various important sources of mutual gains from further integration: consumers would gain access to a wider range of product varieties within sectors; firms and countries would obtain efficiency gains due to further specialization in different varieties or stages of production.

Other B&R economies are only weakly exposed to competition shocks associated with further integration with China. Tajikistan, Myanmar, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Kyrgyzstan, Bangladesh, Mongolia, and Timor-Leste source a sizable share of imports from China, but have an export structure that differs considerably from that of China. To the extent that differences in export structure reflect underlying differences in production structures, these economies are only weakly exposed to Chinese import competition in their own markets, even though they source a large share of imports from China. Mutual gains from further integration with China are likely to derive mainly from further exploitation of the corresponding comparative advantages. The degree to which B&R economies are exposed to competition from China in third-country markets is relatively higher in Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, Philippines, India, Singapore and Indonesia. If Chinese exports become relatively more expensive (e.g. due to further increases in labor costs or exchange rate movements), these countries would likely gain market share in their corresponding export markets. Conversely, if Chinese investments in robotization make its exports more competitive, these economies may lose market shares.

Mongolia, Hong Kong SAR, China, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Oman, Turkmenistan, and the Republic of Yemen are highly exposed to demand shocks from China. A large share of exports from these economies is to the Chinese market, and the export structure of these countries displays a high degree of similarity with China’s overall import demand. China is also an important destination for Lao PDR, Uzbekistan and Myanmar and Iraq, although the export structure of these economies is quite different from the structure of China’s overall import demand. Finally, Malaysia, Philippines and Singapore export a sizable share of exports to China and have an export structure that is relatively close to the structure of Chinese multilateral imports, suggesting that these economies are also strongly exposed to China’s demand shocks.

While deeper economic integration typically generates gains at the country-level, it also imposes adjustment costs within countries. These costs are associated with reallocations of workers across sectors, regions and occupations triggered by sector-specific competition and demand trade shocks. Countries more exposed to competition shocks from China are likely to face stronger adjustment costs. Policies to deal with these trade shocks may include general inclusive policies, such as social security and labor policies (including education and training). Well-designed credit, housing and place-based polices may also facilitate adjustment. Trade-specific adjustment programs may play a complementary role. B&R economies more exposed to competition shocks should consider whether their inclusive policies are appropriate to deal with the adjustment costs imposed by trade shocks, and potentially include these policies in the negotiated trade package. While this paper aimed to provide a general overview of the exposure of each B&R economy to supply and demand shocks associated with further integration with China, more definite conclusions require complementary analysis based on production and employment data, along with a deeper assessment of country-specific institutions.

Please click to read full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Bridge-building initiative helps Beijing and Manila get over the troubled waters of the South China Sea dispute.

While recent extreme weather events mean that the Philippines' massive infrastructure development programme may have to be re-designated as 'Re-build, re-build, re-build,' they certainly won't suffice to derail the key projects already commissioned in any significant way. Nor will they undermine the dramatically improved relationship between the country and China, a relationship that, in the past, was more strained than productive. Now, though, against the ever-expanding backdrop of the mighty Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the two countries are committed to building bridges. Quite literally.

As the damage caused by recent super-typhoon Mangkhut underlines, the Philippines is more vulnerable than most when it comes to incidences of extreme weather. As an archipelagic country, made up of more than 7,600 islands, building and maintaining bridges is an essential element in its economic development. The devastation left behind by the storms and typhoons that all too frequently strike the country – particularly in the case of its fragile bridges and viaducts – is made all the worse by the fact that the country still has far fewer such structures than it really needs.

There are, for example, only 19 bridges spanning the 27km-long stretch of the Pasig River that wends its way through Manila, the national capital. By comparison, the 13km of the Seine River in Paris is spanned by 37 such structures during the course of its meanderings through the French capital.

With this infrastructural shortcoming also a feature of many of the Philippines' other major cities, weather damage aside, extreme traffic congestion is now endemic, while bottlenecks caused by the restricted number of crossing points are commonplace. To try to remedy this, during July 2016-June 2018 the government completed retrofitting / strengthening work on 642 bridges, together spanning more than 29km. Some 939 bridges, spanning about 40km in total, were also wholly refurbished, while 204 new bridges (8km in all) were constructed. This, though, is only scratching the surface.

Given the immense costs involved in wholly upgrading the country's connectivity and transport infrastructure, it was inevitable that China would emerge as the only viable source of investment. Fortunately, the country's needs seem to be very much in line with the aims of the BRI, China's ambitious international infrastructure development and trade facilitation programme.

From China's point of view, the Philippines has a clear role to play in the bigger BRI picture. Most obviously, with a population in excess of 104 million, it is a ready market for Chinese exports, with its status as one of the fastest-growing economies in the ASEAN bloc only likely to enhance its allure. Improved connections and, consequently, improved relations would only ease access to this market.

On top of that, there is the country's geographical significance. China has already earmarked the Port of Davao, some 946km to the southeast of Manila, as a key stopping-off point and consolidation hub for the planned expansion of its trade in Southeast Asia and the South Pacific. To that end, it is committed to funding the redevelopment of the port as part of its wider investment commitment to the Philippines.

To date, China has pledged to back large-scale Philippine infrastructure projects to the tune of US$7.34 billion. This, though, is only part of the broader $24 billion agreed during the 2016 state visit to Beijing by Rodrigo Duterte, the President of the Philippines. Tellingly, since Duterte took office in May 2016, there has been a massive 5,682% increase in Chinese investment in the Philippines.

In more specific terms, earlier this year, China delivered on its pledge to provide PHP4.13 billion (US$78 million) of funding for two bridges on the Pasig River, with work beginning on both in July. The first project is actually a replacement for the 506-metre Estrella-Pantaleon bridge that connects Makati City and Mandaluyong City. The second is the all-new 734-metre Binondo-Intramuros Bridge, which will connect two of Manila's most historic districts.

More recently, in late September, the Chinese government agreed to finance and construct the PHP1.5-billion Davao River Bridge-Bucana, part of the 18km Davao City Coastal Road Project. At the same time, China also signed off on a $13.4 million grant for a feasibility study on plans for the massive Panay-Guimaras-Negros bridge project.

Financing for these projects is mainly being provided via the China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA), which only opened its doors in April this year. Despite its relatively recent establishment, the Philippines has already submitted 12 prospective big-ticket infrastructure projects to the agency for consideration. These are believed to include the Luzon-Samar (Matnog-Alen) Bridge; the Dinagat (Leyte)-Surigao Link Bridge; the Camarines Sur-Catanduanes Friendship Bridge; the Bohol-Leyte Link Bridge; the Cebu-Bohol Link Bridge and the Negros-Cebu Link Bridge.

With relations between China and the Philippines at a high point, despite the still-simmering South China Sea territorial disputes, it seems safe to assume that many of these projects will be greenlit. Indeed, it has been widely anticipated that Xi Jinping, the Chinese President, will give his formal assent to the proposals during his state visit to the Philippines later this year.

Marilyn Balcita, Special Correspondent, Manila

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Joanna Konings, Senior Economist, ING

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is increasing transport connections between Asia and Europe with potential consequences for international trade. Trade between the countries involved accounts for more than a quarter of world trade, so better connections and the lower trade costs that come with them could have a significant global impact. A halving in trade costs between countries involved in the BRI could increase world trade by 12%. Countries in Eastern Europe and Central Asia stand to benefit most, but the benefits will depend on where trade costs fall. There are already some opportunities to transport goods via rail between China and Europe, which may appeal to the wide range of industries with time-sensitive inputs and products. It could take many years before other impacts of the BRI are seen. Many projects are under construction, and the BRI is open-ended. Trade facilitation barriers between countries also need to be addressed……

Opportunities and growth

Rail vs air and sea transport for EU-China trade

Rail transport is only used for a small share of trade between the EU and China, and the BRI is not expected to change this. Nonetheless, interest in rail transport between Europe and China is understandable because the speed of transport is a key dimension of EU-China trade. Time-sensitive goods account for more than three-quarters of the value of China’s exports to the EU, and more than 60% of the EU’s exports to China. Speed is important where goods like the components of cars, phones and computers, are part of supply chains spanning many countries. For finished products, like seasonal clothing, fast delivery can be important where demand is very changeable. As rail transport becomes more accessible, importers and exporters can use rail transport when previously they have only had the options of air and sea transport. Faster delivery frees up working capital and reduces capital costs, and rail transport also offers a much greener alternative to air transport for the most time-sensitive trade flows.

Impacts on international trade

Trade between Asia and Europe (not including trade between EU countries) accounts for 28% of world trade, so making those trade flows easier has a large potential impact. The size of this impact depends on the sensitivity of trade to changes in relative costs, which can be estimated in gravity models of international trade. These models describe trade flows in terms of the size of countries and the relative costs of trade between them. The relationships in the gravity model also allow us to calculate approximate individual country effects when trade costs change.

The impact of the BRI will also depend on where trade costs fall as a result of BRI projects. Trade costs may fall between a very small set of countries, or much more widely across Asia and Europe. We investigate this using three scenarios. In each case, we assume that the BRI will in the long run lead to a 50% fall in trade costs between a different set of countries:

- New Eurasian Land Bridge: countries along the New Eurasian Land Bridge economic corridor (China, Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus and Poland), which is broadly the route of most current international rail services between China and Europe. Trade costs are also assumed to halve between countries along the New Eurasian Land Bridge economic corridor and the EU15, Cyprus and Malta (costs are not assumed to fall between the EU countries).

- BRI corridors: countries along all BRI economic corridors, covering the majority of Asia and the EU (again, costs are not assumed to fall between EU countries)

- BRI corridors and partners: as in the BRI corridors scenario plus countries in Europe and Asia which have signed BRI implementation and co-operation agreements with China, including Central and Eastern European countries, Indonesia, Singapore, Saudi Arabia and Egypt.

When trade costs fall between these countries, trade between them increases. The resulting impacts on world trade range from a 4% increase in the scenario involving the New Eurasian Land Bridge countries, to 12% when trade costs fall between all countries involved in the BRI.

As mentioned above, the relationships in the gravity model allow us to calculate approximate individual country effects when trade costs change. When trade costs are halved between all countries involved in the BRI, there are estimated increases in trade of 35% to 45% for Russia, Kazakhstan, Poland, Nepal and Myanmar. Overall, countries in Central Asia and Eastern Europe see the largest increases.

Some countries involved in the BRI do most of their trade with other BRI countries (China and the EU15 countries, on the other hand, do a relatively small amount of their total trade with other BRI countries). Those countries benefit from the fall in trade costs affecting the majority of their trade. Although all countries increase their exports to Greater China, the fall in costs also benefits the bloc of EU15 countries, as the other large trade partner of most countries in the region. This is especially the case for Eastern European countries, highlighting the importance of where trade costs fall in determining which countries will benefit from the BRI. If the BRI did not produce a fall in trade costs between countries in Eastern Europe and the bloc of EU15 countries, then the overall impact of the BRI on Eastern European countries would instead be relatively small.

Within countries, different industries may feel the effects of competition in other countries having been brought a step closer through lower trade costs. This will stimulate competition and potentially also innovation, with benefits for consumers, but some industries and sectors may lose out to competitors from other BRI countries. 50% is undeniably a large fall in trade costs, but it is chosen due to the influence that the BRI will have on transport costs and trade facilitation, which are also factors that research suggests are big influences on trade costs. The WTO has calculated that improvements in trade facilitation could reduce BRI countries’ trade costs by between 12% and 23%. Transport costs are consistently found to be an important part of trade costs, though estimates vary widely (partly because of the many different measures of transport costs in empirical studies). 8 The combined effect of trade facilitation improvements estimated by the WTO (12-23%) and a halving in transport costs (33%, on the assumption that transport costs are two-thirds of trade costs) would be one way of reaching a 50% reduction in overall trade costs.

The mix of transport and trade facilitation cost reductions is likely to differ for every trade flow. For some, a significant fall in costs might come through switching from air transport to rail or rail and sea. Others might benefit from a new shorter route opening up to a destination market, or more efficient border crossings or port operations along a particular route. In practice the composition of the fall in costs is likely to make a difference: Ramasamy et al (2017) show that trade facilitation is critical to realising the trade gains from improvements in infrastructure in BRI countries. And transport infrastructure needs to increase to some extent to handle the higher trade flows (though the current practice of slow steaming in the shipping industry also provides for some spare capacity within the current infrastructure).

How far costs may fall is really a question about how long the BRI policy will exist. The BRI projects currently under construction are expected to be completed in the coming five years, and the BRI is open-ended (and ultimately aiming for “unimpeded trade”), so new projects are likely to be initiated in that time. As a result, any significant fall in trade costs due to the BRI is likely to take at least five years, and more likely ten, or even longer. If trade costs are slow to fall, effects on world trade growth will be small in any given year. Significant falls in trade costs, even over a long period, could lead to large impacts on international trade.

Please click to read full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By KPMG China

The Greater Bay Area (GBA) represents a national development strategy to economically and socially integrate the nine cities in Guangdong’s Pearl River Delta, as well as Hong Kong and Macau, to create a world-class bay area.

The GBA is well-positioned to become the most diversified city cluster in the world – by leveraging its strengths in financial and professional services, high-tech manufacturing, technology and innovation, and tourism and leisure – and provides significant opportunities for companies in China. The increased connectivity and integration of the GBA will also enhance the movement of goods and services, capital, people and information within the region, and facilitate the implementation of the 13th Five-Year Plan and the Belt and Road Initiative.

This publication provides an overview of the key trends and developments in the GBA, and serves as a guide to how businesses can partner with KPMG to drive growth in the region.

The diverse range of industries and strengths across the GBA’s cities provides significant opportunities for companies that are looking to enter or build on their existing presence in China. KPMG is well-positioned to advise clients on their investments and business strategies in the GBA.

Innovation and technology to drive smart cities: The transformation of the GBA into an innovation and technology hub remains a key priority. This presents a number of opportunities for businesses, innovators and other key stakeholders to develop and test their ideas, deepen the talent pool, connect with strategic partners, and drive innovative and digitally-driven growth.

Building a solid foundation of infrastructure and real estate: Significant infrastructure development is a key pillar of the vision for the GBA. This is expected to generate high volumes of infrastructure and real estate development, creating plenty of investment opportunities for existing and new players in the region.

M&A activity set to soar: As the GBA continues to evolve, businesses operating in, or looking to enter, the market will need to review their medium and long-term strategies to assess how best to capitalise on the many opportunities.

Connected capital markets to drive growth: With a deep capital pool comprising both institutional and retail investors, the GBA remains an attractive and leading region for listing and trading securities, both for domestic and international businesses.

Financial institutions to capitalise on cross-border flows: The GBA stands as a major market for financial and high-value industries. The region’s size, as well as the different stages of development among its cities, present significant opportunities for the financial services sector.

Strategies to optimise business opportunities: The increasing connectivity within the GBA, as well as the region’s diverse range of industries across its cities, provide significant opportunities for companies that are looking to enter or build on their existing presence in China.

Navigating a new tax landscape: Enterprises participating in the GBA have to plan ahead and properly manage tax risks and utilise tax incentives to capitalise on opportunities presented by the greater movement of people and capital.

Mobilising and aligning talent: In order to achieve long-term success in the GBA, it will be important for companies to put the right people and organisational structures in place.

Please click to read full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Derek Scissors, American Enterprise Institute

Key Points

- China is investing much less in the US than it did just a year ago. It has never invested much in the Belt and Road. Yet China’s global investment spending remains healthy, with impressive diversification across countries and the reemergence of private firms.

- Construction and engineering is considerable but unlikely to expand much, as the projects drain China’s foreign reserves. Construction in the Belt and Road alone is rising because the number of countries is rising, not because China is more active.

- The US is about to change its investment review framework with new legislation. This is a step forward, but problems remain. The new framework appears complex while foreign investment thrives on certainty. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States must be properly resourced or reform will prove meaningless.

American headlines stress coming restrictions on Chinese activity in the US. Global headlines stress transformation wrought by the Belt and Road Initiative. Actual measurement shows China has not invested heavily in the US since early 2017 and never invested heavily in the Belt and Road (BRI).

Several large transactions have driven China’s 2018 outbound investment, featuring a $9 billion transport play in Germany, plus a series of health care acquisitions. The top five investment targets in 2018 to date sit on five different continents. China’s overseas spending habits are more diverse than many observers believe.

The China Global Investment Tracker (CGIT) from the American Enterprise Institute is the only fully public record of China’s outbound investment and construction. Rather than presenting only totals or a map, all 3,000 transactions are profiled in a public data set. The CGIT estimates the number of investments in the first half of 2018 dropped 15 percent from the first half of 2017. Based on the number of transactions and total amount spent, the first half of 2018 strongly resembles the first half of 2015, before the pace of capital exit first soared and then was curbed by Beijing.

There are encouraging signs. Transport, energy, and metals investment led in the first half but, contrary to Beijing’s insistence, entertainment and real estate are not dead. Perhaps the single best development is private Chinese firms are spending again this year. While the raw quantity is lower, the private share of investment is back to its 2016 level. If 2018 continues to follow the pattern of 2015, total investment volume will be in the $115-$130 billion range for the year. Another $1 trillion globally could be added by the end of 2024.

Investment by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is often conflated with construction of rail lines, power plants, and so forth. Construction does not involve ownership, as investment does. Since 2005, there are more construction contracts worth $100 million or more than investments, though the average construction deal is smaller. In the first half of 2018, the PRC initiated at least one large construction contract in over 40 countries, chiefly in energy and transport.

Chinese engineering and construction is the core of the BRI. Using the latest, 76-member version of the BRI for the largest possible size, the BRI accounts for over 60 percent of Chinese overseas construction since its inauguration in the fall of 2013, with that pace holding in 2017-18. On this tally, in not quite five years, BRI construction has been worth more than $250 billion. In contrast, the current set of BRI countries accounts for less than 25 percent of the PRC’s outbound investment over the period, a bit more than $150 billion total.

BRI investment weakness is especially troubling for Beijing because the preferred location for Chinese companies is closing off. The PRC’s investment in the US exceeded $50 billion in 2016, fell by more than half in 2017, and was only $4.5 billion in the first half of 2018. Congress has been crafting legislation to tighten oversight of Chinese ventures since the 2016 surge, but there is less and less to oversee. Chinese enterprises exist at the sufferance of the Communist Party and must be treated accordingly. The American goal should be to do so yet still offer clear, stable policies to welcome investment when national security is not involved….

Please click to read full report.