Hong Kong Maritime Services Cluster: Meeting the Challenges

Hong Kong Maritime Services Cluster: Meeting the Challenges

A Difficult Time for the Global Shipping Industry

The global shipping industry has struggled since the 2008 financial crisis due to soft demand and overcapacity. With the rare exception of increased transportation of LPG on the back of strong GDP growth in India and some Southeast Asian economies in 2015, the softer Chinese economy and falling commodity prices more than offset the positive blip and continue to cast a negative outlook over the industry, with ship owners of most vessel types finding it hard to see any bright spots in 2016.

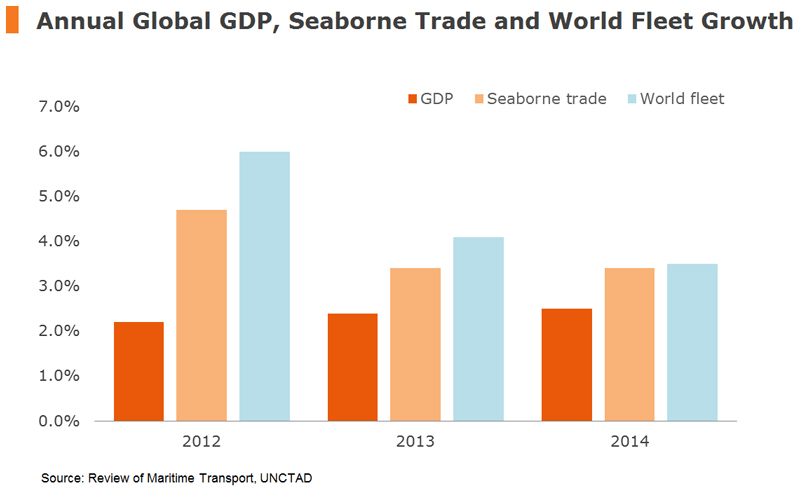

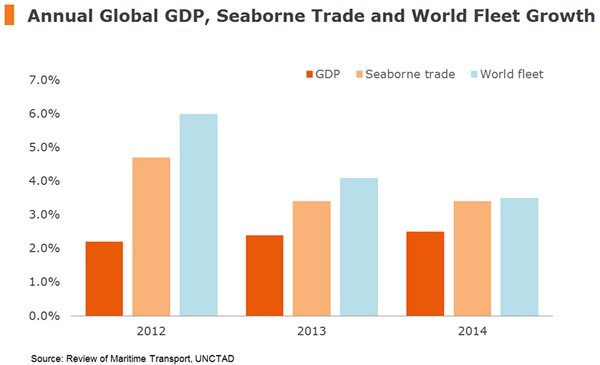

It has been reported in recent months that many ship owners have continued to place orders for large-sized vessels despite a weak trade outlook, apparently in an effort to reduce operational cost at the margin by achieving better economies of scale. According to the latest Review of Maritime Transport issued by UNCTAD in October 2015, growth of the world fleet in deadweight tonnage (DWT) outpaced that of global GDP and seaborne trade in the period of 2012-2014. As the figure below shows, the global economy and seaborne trade grew at an annual average of 2.4% and 3.8%, respectively, during that period, while the size of the world fleet expanded by a larger magnitude of 4.5%.

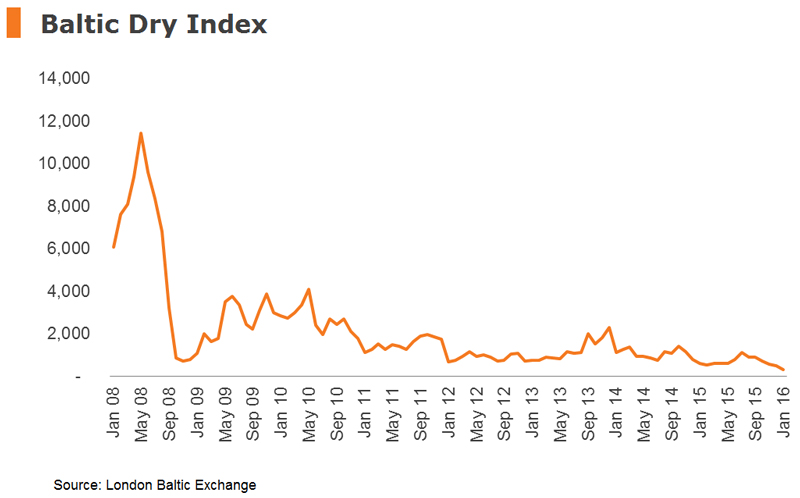

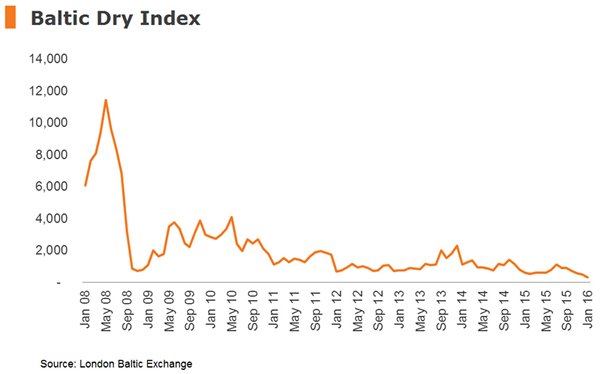

According to Clarksons Research, the world fleet is estimated to have reached 1.8 billion DWT in 2015, translating to a year-on-year (YOY) growth of 3%, equal to the projected global GDP growth, but slightly ahead of the seaborne trade growth rate of 2% for the same year. For the container segment alone, it was estimated that new capacity of almost 1.6 million TEUs was added in 2015, a time when more than one million TEUs of idled container capacity had already been reported. Against the background of such supply-demand imbalance, the Baltic Dry Index (BDI), a key industry tracker of the daily earnings of ships carrying dry commodities such as metals and grains, plunged to a record low (of 317) in January 2016, more than 95% below its 2008 peak.

The Baltic and International Maritime Council (BIMCO) has warned the shipping industry to brace itself for a challenging 2016 amid subdued global trade growth and an economic slowdown in emerging markets – including China, the world’s “factory” and largest exporter. Amid weak demand, shipping-freight rates are likely to remain depressed prior to further supply-side adjustment and market consolidation to alleviate the market imbalance, in particular through more careful management of deployed capacity, placement of new orders and the scrapping of old vessels.

A Growing Hong Kong Shipping Community Despite the Global Downturn

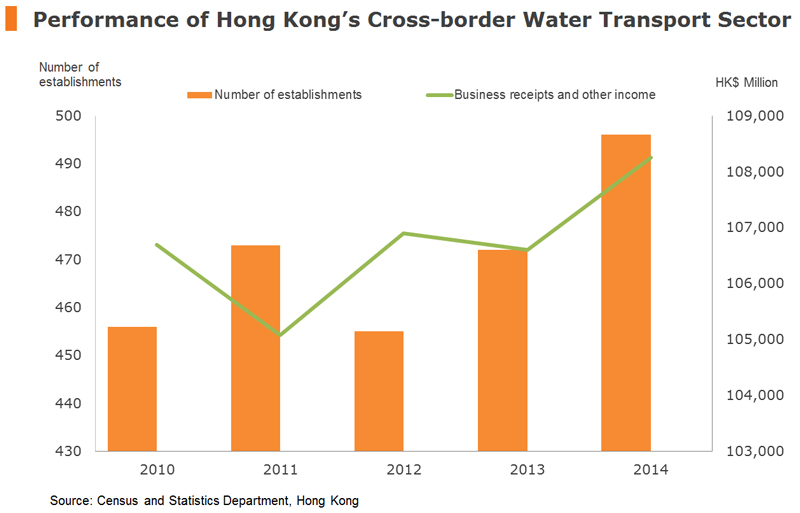

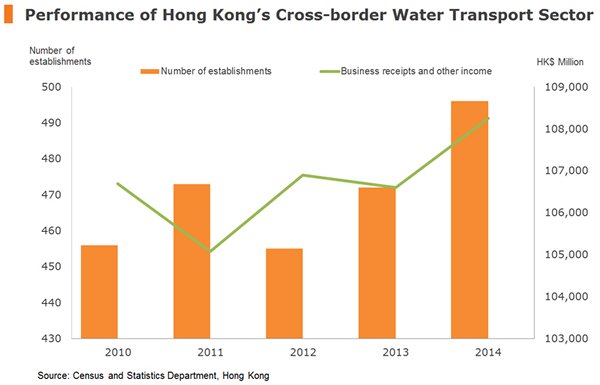

Given the unfavourable external environment, perhaps the only encouraging development for Hong Kong’s shipping community is that the industry has performed relatively well over the past few years, showing great resilience despite the precipitous fall in freight rates. Based on the latest data released in November 2015, the number of business establishments in Hong Kong’s cross-border water transport industry[1] increased by 8.8% between 2010 and 2014, to 496 from 456, while business receipts during the same period also rose to HK$108.3 billion, 1.5% above its 2010 level.

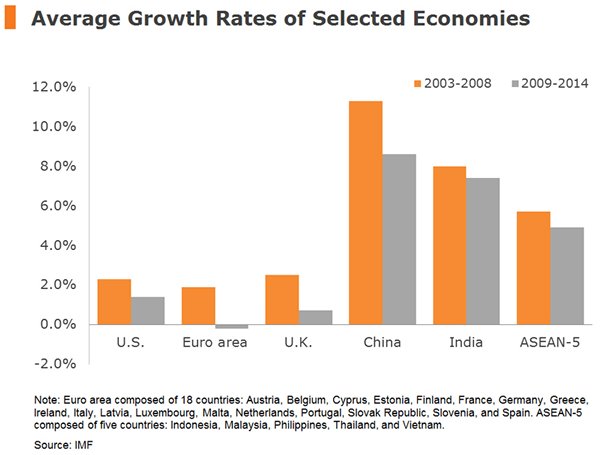

Hong Kong’s shipping industry, as represented by the cross-border water transport establishment, managed to register income growth in 2014 and enjoyed a much stronger performance than that indicated by general freight rates with the BDI as a proxy, which showed a YOY fall of more than 70%. This was also borne out to an extent by the positive equity price performances of Hong Kong-listed shipping companies in that year[2]. There could be a host of reasons behind the relatively stronger performance of Hong Kong’s shipping companies. Among other things, Asian economies were more robust in 2014 than those in Europe and the Americas, thereby generating stronger demand for intra-regional freight transportation, while extra-regional freight traffic was at a lower ebb.

The global shipping industry has continued to suffer from the overhang of multi-year adjustment since the 2008 financial crisis, and is now grappling with the additional challenges of a global economic slowdown aggravated by a stuttering Chinese economy, as well as the lingering problem of vessel overcapacity. While the short-term outlook shows few bright spots, the long-term view is more positive with seaborne trade expected to double by 2030, although industry consolidation and the attendant adjustment over the medium-term is likely to be difficult.

Hong Kong: A Vibrant Maritime Services Centre

Certainly, the performance of Hong Kong’s shipping industry has a strong bearing on the performance of other strands of maritime services, such as shipping insurance, finance, broking and legal services. The performance of individual segments of Hong Kong’s maritime service cluster can at best be examined by a very limited pool of available official statistics, particularly in relation to business receipts. [3] For example, no official statistics are available for business receipts of Hong Kong’s ship insurers. However, official figures released in September 2015 show that the number of authorised ship insurers in Hong Kong increased by two, to 86, in the period 2013 to 2014. More remarkably, gross shipping insurance premiums went up by 18% to HK$2.36 billion in 2014, followed by a YOY increase of 6% in the first six months of 2015.

As an international maritime centre (IMC), Hong Kong needs to reinforce its offerings in the face of growing regional competition and challenges due to the economic downturn. Hong Kong has always thrived as a leading IMC in Asia, thanks in no small measure to its rich maritime history and a large pool of ship owners and operators. As a pre-eminent port since the 1970s, the city has gradually expanded to emerge as an all-encompassing IMC, offering a comprehensive range of high-value-added maritime services including ship management, ship broking, shipping insurance, finance and legal services, along with the traditional port and shipping businesses.

The sections below will examine the long-term fundamentals that will play in Hong Kong’s favour, allowing it to seize fresh business opportunities arising from global industry consolidation, regional economic integration, as well as China’s attempt to foster stronger international cooperation through the Belt and Road Initiative, and the country’s economic strategy to rebalance its economy.

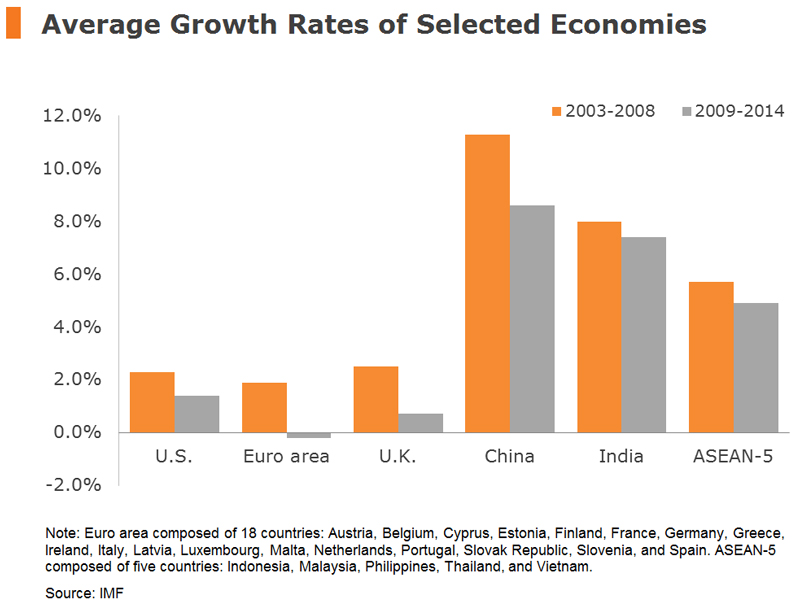

Shift of economic gravity and maritime power from West to East

It has become apparent that economic gravity has shifted from the West to the East in the past decade or so, and more profoundly since the outbreak of the 2008 financial crisis. In the intervening years, China has overtaken Japan to become the world’s second-largest economy, and displaced the US as the largest exporter and trading nation. Although China’s GDP growth fell to a 25 year low of 6.9% in 2015, one should not overlook the fact that the Chinese economy last year was 75% bigger than in 2008 in terms of real GDP. It would be a daunting task for a major developing economy such as China to keep sprinting at a neck-breaking pace while the rest of the global economy is experiencing uneven growth, with some nations recovering faster than others but a number of them striving to prevent a return to recession.

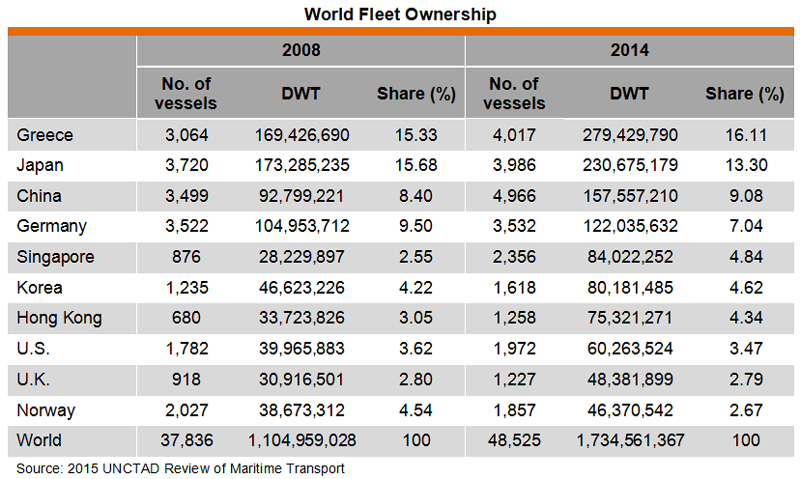

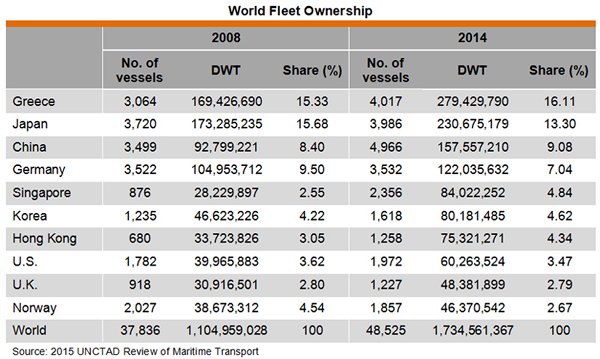

Asian economies have been rapidly expanding their presence in the international maritime community, according to world fleet ownership statistics, and it’s a trend that is expected to continue despite the ongoing global economic downturn. In 2014, half of the top 10 ship-owning territories were in Asia, accounting for 36% of the world’s total tonnage. By comparison, the top four European territories accounted for 29%.

Back in 2008, Europe dominated the sea, with five territories in the top 10, representing 35% of the world’s total fleet in terms of DWT. Another 31% was controlled by four Asian territories. In terms of DWT growth, Asian territories out-performed the world growth average of 57% in the period of 2008-2014. Among Asia’s top ship owning territories, Singapore showed the strongest growth (198%), followed by Hong Kong (123%), Korea (72%) and the Chinese mainland (70%). In terms of ship registration, Hong Kong was ranked fourth globally in 2014, accounting for 8.6% of the total tonnage.

Increasing regional opportunities

Before the 2008 global financial crisis, there was a prevalent view that world trade growth had been expanding at about twice the pace of world GDP growth. This trade-to-GDP relationship seems to have broken down over the past few years, with a slowdown in growth of world trade to just above that of world GDP growth, while both are eclipsed by world fleet growth. Nevertheless, increased regional attempts for further economic integration are expected to provide additional impetus to intra-Asia trade. According to the Asian Region Integration Centre, intra-Asian trade accounted for 55.6% [4] of the region’s total trade in 2014, up from 45.5% in 1990, and is expected to further expand, taking into account in particular the formation of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) in December 2015.

The AEC, with more than 600 million people, is envisioned to be a single market and production base, characterised by the free flow of goods, services, and investments, as well as a freer flow of capital and skills. At sub-regional level, the AEC is expected to boost intra-ASEAN trade to 30% of total trade in 2020, from about 25% in 2014. On the other hand, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), formally signed on 4 February 2016, creates the world's biggest free-trade area by bringing together 12 Pacific Rim countries [5] and is conducive to Asia’s extra regional trade. According to the World Bank, TPP economies account for about 36% of the world’s GDP and 25% of global trade, with the deal expected to lift trade of TPP members by 11 percentage points by 2030.

All these developments, along with the increased presence of ship owners in Asia, are expected to promote trade and help alleviate the demand-supply imbalance of freight vessels over the longer term, while also creating the incentives for maritime service providers to be clustered in the region. Despite the rough short-term environment, the annual volume of world seaborne trade is expected to increase to 20 billion tonnes by 2030, from 9.8 billion tonnes in 2014, based on projections by Lloyd’s Register. Trade routes connecting intra-Far East, Oceania and the Far East, the Far East and Latin America, and the Far East and the Middle East are seen as the drivers and point to the huge potential of Asia’s shipping industry.

Hong Kong’s IMC to Embrace Competition and Seize Opportunities

With world trade growing only slightly faster than world GDP, competition in freight transportation and shore-based logistics activities can only get stronger. As mentioned above, orders for bigger vessels and container ships are still being placed in a bid to achieve greater economies of scale amid the global economic downturn. Apart from meeting the challenges from competition in terminal, freight transportation and related logistics activities, there is an increasing recognition that Hong Kong needs to further enhance its appeal as a maritime services centre in Asia.

Hong Kong’s strong fundamentals and the London lesson

Undoubtedly, many overseas maritime companies set up their businesses in Hong Kong because of the city’s great location, comprehensive logistics network and huge pool of maritime-related service providers. Take the financial sector as an example. Hong Kong is an international financial hub with one of the most active capital markets and the world’s largest offshore RMB market. It has the expertise and the connections to serve as a stronger maritime finance centre in Asia by offering fundraising and myriad financial services.

The Hong Kong government has repeatedly noted that the city needs to reinforce the maritime services cluster and develop high-value-added maritime services, building on the strengths of its existing terminal business. In particular, there is a strong emphasis on emulating the success of London and specialising further in high-value, desk-based activities, which are seen as the drivers fuelling the continual growth and development of the city’s shipping industry over the longer term.

In London’s case, physical activities have long migrated to other parts of the country. However, the city remains one of the world’s most important maritime services centres with an impressive cluster of ship brokerage, insurance, finance and arbitration services due to its rich maritime history and skilled labour base. For example, the city accounts for approximately a quarter of global maritime insurance, and it is reported that British firms are responsible for arranging 30 40% of the world’s dry-bulk chartering contracts.

In the 2016 Policy Address, the Hong Kong government reiterated its commitment to strengthen Hong Kong’s role as an international maritime services hub in Asia. Among other things, a new Hong Kong Maritime and Port Board (HKMPB) will be formed by merging the existing Maritime Industry Council and the Port Development Council. This will aim to better develop a high-value added maritime services cluster through promoting manpower development, marketing and research on all fronts, while formulating strategies to enhance Hong Kong’s status as an international transportation centre.

Apart from the city’s free-port status, Hong Kong has adopted measures to improve its tax regime. As of December 2015, Hong Kong had entered into double taxation avoidance arrangements (DTAAs) specifically related to shipping income with 40 of its major trading partners. It is now actively looking to establish similar arrangements with its remaining trading partners.

In terms of human capital investment, the HK$100 million Maritime and Aviation Training Fund (MATF) was launched in 2014 to support a number of training and incentive schemes. This funding programme will provide support to young people or in-service practitioners to undertake relevant training courses and pursue professional studies, enhancing the overall competency and professionalism of the maritime industry in the medium to long term.

Hong Kong’s favourable business environment is further enhanced under the latest CEPA agreement signed between Mainland China and Hong Kong, which will allow basic liberalisation of trade in services between the two from June 2016, thereby opening the door for Hong Kong maritime services providers to fully tap into Mainland China.

The Belt and Road opportunities

At a time of a market downturn and continuing business consolidation, Hong Kong needs to be on the lookout for business opportunities. As China’s most international city, Hong Kong stands to benefit considerably in the years to come from China’s grand strategy known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The BRI was first proposed by President Xi Jinping in 2013, comprising two main components: the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. The aim is to expand trans-continental connectivity by promoting economic, political and cultural co operation from Asia to Africa and Europe. The BRI is expected to connect 4.4 billion people in more than 60 economies with a gross economic volume of about US$22 trillion.

In 2015, the development blueprints for the BRI were outlined. The value of the proposed BRI-related infrastructure investment in China amounts to some US$160 billion, with total investment in countries along the route expected to reach almost US$900 billion. In implementing this ambitious BRI strategy, enormous opportunities will be created for Hong Kong companies and service providers. As the economic centre of gravity continues to shift east, Hong Kong is poised to become the “super connector” linking Chinese maritime companies to Asia and Europe, leveraging its geographic position, international connectivity, and institutional advantages under “One Country, Two Systems”.

Above all, the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, which links China with Europe through the South China Sea and Indian Ocean, will create fresh demand that supports the long-term growth of the shipping industry. At the same time, international maritime service providers along the Belt and Road will find it beneficial to establish regional offices in Hong Kong, using its maritime services to tap into the mainland market. China has already emerged as a major shipping centre [6] and the world’s biggest shipbuilder. Commercial principals of Chinese shipping companies might also find it advantageous to set up or augment their presence in Hong Kong, which boasts the world’s fourth-largest shipping register.

In forthcoming articles, we will discuss the developments of different maritime service sub-sectors in Hong Kong, including ship broking, ship management, marine insurance, ship finance and maritime law.

[1] According to Statistics on Business Performance and Operating Characteristics of the Transportation, Storage and Courier Services Sector in 2014, the following entities are grouped under the cross-border water transport industry: Ship agents and managers; local representative offices of overseas shipping companies; ship owners of sea-going vessels for passenger transport; ship owners of sea-going vessels for freight transport; operators of sea-going vessels for passenger transport; operators of sea-going vessels for freight transport; ship owners and operators of passenger vessels moving between Hong Kong and the ports in the Pearl River Delta (PRD); and ship owners and operators of freight vessels moving between Hong Kong and PRD ports. The cross-border water transport industry is taken as a rough indication of Hong Kong’s shipping industry for statistical comparison of business establishments. However, it excludes, among other things, ship brokers, insurers, finance companies, surveyors, and classification societies.

[2] For instance, OCCL and COSCO posted YOY gains of 19% and 8%, respectively, in 2014.

[3] In the Summary Statistics on Shipping industry of Hong Kong for September 2015, the shipping industry refers to such industry groups as ship agents and managers; ship owners of sea-going vessels; operators of sea-going vessels, and shipbrokers. Statistics on business activities of the following areas are excluded: shipyards; boatyards; ship surveyors; maritime insurance; maritime legal services; ship finance; and classification societies.

[4] Asian Economic Integration Report 2015, Asian Development Bank

[5] The 12 members of the TPP are: Australia, Canada, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, the US, Vietnam, Chile, Brunei, Singapore and New Zealand

[6] In 2014, seven out of the world’s top 10 ports with the highest throughput were in China, namely Shanghai, Shenzhen, Hong Kong, Ningbo, Guangzhou, Qingdao and Tianjin.

| Content provided by |

|