Vietnam

Concerns over China's geopolitical intentions remain a challenge for Belt and Road projects in Southeast Asia.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has not moved quite as quickly in Southeast Asia as it has in South or Central Asia. This is partly down to ongoing tensions in the South China Sea, which have raised concerns among some countries in the region as to China's geopolitical intentions.

At present, the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is caught between these concerns and a desire to enhance its already strong trade relations with China. Overall, there is a recognition that the region would benefit from BRI-driven investment, with the Asian Development Bank maintaining US$1 trillion needs to be spent on infrastructure development by 2020 just to maintain current growth levels.

Xue Li is the Director of International Strategy at the Beijing-based Chinese Academy of Social Sciences' Institute of World Economics and Politics. Outlining the challenge facing the BRI, he said: "We haven't done enough to attract countries in Southeast Asia. On the contrary, their level of fear and worry toward China seems to be rising."

For Southeast Asia, the Singapore-Kumming Rail Link is something of a test case. This high-speed link will run through Laos, Thailand, and Malaysia, before terminating in Singapore, a total distance of more than 3,000km. To date, though, not everything is going the way China might have preferred.

In Laos, construction has been delayed. It is also likely that all of the work will have to be paid for by China, as Laos cannot afford the $7 billion required. In Thailand, meanwhile, negotiations have broken down. The Thais now want to build only part of the line – short of the border with Laos – and finance it themselves without Chinese involvement.

As to which company will build the Singapore-Malaysia stretch, that will be decided next year, with Chinese – as well as Japanese – firms emerging as the current frontrunners. Across the board, though, there is unhappiness at what is considered excessive demands and unfavorable financing conditions on the part of the Chinese. Back in 2014, Myanmar pulled out of the project, citing local concerns over the likely impact of the project.

A similar situation has now arisen in Indonesia. The $5.1 billion Jakarta-Bandung High-speed Railway Project, seen as an early success for the BRI, may now require significantly more funding. Indonesia is also unhappy at what it terms 'incursions' into its waters by Chinese fishing boats. It is, however, trying to downplay their significance as a 'maritime resource dispute' in a bid not to deter Chinese investment in the country. The Philippines is, by comparison, less conciliatory, largely because China is not one of its key trading partners. At present, the Philippines and Vietnam are the ASEAN nations most cynical with regards the ultimate intentions behind the BRI.

Singapore, a country with no direct stake in the South China Sea, remains strongly committed to the Initiative. In March this year, Chan Chun Sing, Minister in Prime Minister's Office, emphasised the importance of BRI as a means of improving links with China and its near neighbours.

He said: "The BRI represents a tremendous opportunity for businesses in Singapore – as well as in the wider Southeast Asian region – to work more closely with China. The more integrated China is with the region and the rest of the world, the greater the stake it will have in the success of the region. The more we are able to work together, the more it will bode well for the region and the global economy."

In line with this, this year has seen a number of Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) signed between China and Singapore. Back in April, one such undertaking was signed between International Enterprise Singapore (IES) and the state-owned China Construction Bank. Under the terms of the memorandum, $30 billion is now available to companies from both countries involved with BRI projects. At present, the two organisations are in discussion with some 30 companies with regards to developments in the infrastructure and telecommunications sectors.

In June, an additional MOU was signed between IES and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China. This has seen a further $90 billion earmarked to support Singapore companies engaged in BRI-related projects.

Ronald Hee, Special Correspondent, Singapore

Editor's picks

Trending articles

China's stake in Laos' sustainable-energy sector paves way for closer long-term Belt and Road collaboration.

China and Laos jointly initiated work on the second phase of the 1,156 MW Nam Ou Cascade Hydropower Project earlier this year. The project, set on Laos' principal river, is seen as one of the country's key contributions to China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

With Laos' GDP for 2016 recorded at just US$15.9 billion, China has shouldered the bulk of the cost of the $2.8 billion initiative in exchange for the concession to operate the hydropower installation for the next 29 years. Once completed, it will comprise seven dams and hydropower stations and have a projected capacity of 1,156 MW, together with an annual energy output of 5,017 GWh.

The lead on the Chinese side has been taken by Sinohydro, a Beijing-headquartered state-owned hydropower engineering and construction company, which entered into an agreement to develop the project on a joint-venture basis with Electricite Du Laos (EDL), the Laos state electricity corporation, which holds a 15% stake in the site. Under the terms of the project, all electricity generated will be sold to EDL. Significantly, Nam Ou is the first project for which a Chinese enterprise has secured the whole basin rights for planning and development.

With work on Phase One completed more than two years ago – comprising construction of the Nam Ou 2, Nam Ou 5 and Nam Ou 6 plants – the site generated its first electricity on 29 November 2015. In total, the capacity of Phase One is estimated at about 540 MW, almost half the total envisaged for the completed project. The groundbreaking ceremony for the second phase was held some five months later and marked the beginning of the work on the remaining plants – Nam Ou 1, Nam Ou 3, Nam Ou 4 and Nam Ou 7. This second phase is scheduled for completion in 2020.

Emphasising the importance of the initiative, Dr Khammany Inthilath, the Lao Minister of Energy and Mines, said: "Once completed, the Nam Ou Cascade Hydropower Project will have a major role to play in the reduction of poverty across Laos. In particular, it will boost the socio-economic development of Luang Prabang and Phongsaly provinces, immeasurably improving the living standards of local residents.

"It will also play an important role in regulating the seasonal drought problems in the Nam Ou river basin. Ultimately, we hope it will ensure downstream irrigation for the region's plantations on a long-term basis, while also reducing soil erosion."

Despite Inthilath's optimism, the project has attracted criticism on a number of fronts. Firstly, there have been concerns over the possible adverse environmental impact of such large-scale hydropower projects, particularly given the scale and number of hydropower developments currently under way along the Mekong River and its tributaries. In addition to the Nam Ou project, China is also involved with several other hydropower installations, including Don Sahong, Pak Beng and Xayaburi.

A second wave of criticism has come from outside Laos, with a number of neighbouring countries expressing concerns that the cumulative effect of the hydropower projects already under way may adversely impact on the flow of the river. To this end, the governments of Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia have all gone on record as objecting to the expansion of Laos' hydropower programme.

It is the sheer scale of Chinese investment in Laos, together with the country's resultant indebtedness, that has triggered a third wave of criticism. By the end of 2016, with $5.4 billion worth of funding already in place, China was by far the largest overseas investor in Laos.

According the Lao government's own figures, by the end of 2016 Chinese companies had signed up for $6.7 billion worth of construction projects in the country – some 30.1% of the total earmarked for Laos' infrastructure upgrade. The overall scale of the deals already in place makes Laos the third-largest market for China in the ASEAN bloc.

Overall, though, taking an active role in China's Belt and Road Initiative has been seen as a good fit with Laos' long-held ambition to shift from being a land-locked nation to becoming more of a land-linked economy. Furthermore, Laos' ongoing co-operation with China on a series of energy projects has underlined the positive relationship between the two countries.

Highlighting this, while speaking at the launch ceremony for Phase Two of the Nam Ou Cascade Hydropower Project, Li Baoguang, the Chinese Consul-General in Luang Prabang, Laos' ancient capital, said: "This year marks the 55th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic ties between China and Laos and there could be no better way of commemorating that than with the commencement of work on this joint venture."

Geoff de Freitas, Special Correspondent, Vientiane

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Longjiang Industrial Park in Vietnam

Bordering China’s southern region, Vietnam is one of its most important ASEAN trading partners. In 2016, the bilateral import and export trade between China and Vietnam amounted to US$88.2 billion, accounting for approximately 20% of the overall trade value between China and ASEAN countries. Many Chinese enterprises, as well as conducting general trading activities with their Vietnam counterparts, have recently invested in the country and set up manufacturing plants there. The textile, garment and electronics industries of China and Vietnam have gradually moved into co-operation as industrial chain partners, further stimulating the export of Chinese upstream products to Vietnam.

China’s direct investment in Vietnam reached US$560 million in 2015, equivalent to 1.8 times the investment in 2010. At the end of 2015, China’s total stock of direct investment in Vietnam was about US$3.37 billion. Chinese manufacturers investing in Vietnam are not only able to lower their production costs by capitalising on the local labour force and land resources, but their operations in Vietnam can also tie in with their overall production plans and development in China as well as the Asia-Pacific region.

More than 320 industrial parks in Vietnam are dedicated to manufacturing activities. As of mid-2016, the cumulative total foreign direct investment (FDI) in these industrial parks amounted to US$150 billion in terms of registered capital, accounting for about half of all FDI inflows into Vietnam. While the majority of provinces in Vietnam have industrial park management offices offering single-window services to help investors choose the most suitable location, most of the large parks are operated and managed independently by private companies. Foreign investors can approach these industrial park management companies directly to learn about the preferential policies available in the parks.

The Longjiang Industrial Park (LJIP), located in Tien Giang Province of Vietnam, is one of them. A comprehensive industrial park invested and developed by Zhejiang Qianjiang Investment Management Co Ltd, it is a key project undertaken by Zhejiang Province under the Belt and Road Initiative. Tien Giang Province is located in the Mekong River Delta region close to Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam’s leading commercial hub, in the south of the country. At the end of 2015, with a total of 78 foreign-investment projects, Tien Giang Province’s cumulative FDI inflows reached US$1.53 billion, accounting for 0.5% of Vietnam’s total.

Tien Giang Province has a population of about 1.73 million, according to the General Statistics Office of Vietnam, of which 0.28 million are urban residents and 1.45 million live in the countryside. LJIP is located in Tien Giang Province’s rural Tan Phuoc District. According to the park’s estimates, the population within a 15km radius of LJIP is between 800,000 and one million, which provides an abundant young labour force.

LJIP was granted a 50-year investment licence by Vietnam’s Tien Giang Industrial Park Authority in November 2007. The park has a planned area of 600 hectares, including 540 hectares of industrial area and 60 hectares of residential and service area. Total investment is estimated to be US$100 million.

Positioned as a comprehensive industrial park, it aims to attract industries in the fields of (1) electronic and electrical products; (2) machinery; (3) wooden products; (4) light industrial products for home use; (5) rubber and plastic products; (6) drugs, cosmetics and medical apparatus; (7) agricultural and forestry products; (8) building materials; (9) papermaking; and (10) new materials.

The park has all necessary infrastructure, such as an internal road network, broadband communications, as well as power, water and sewage systems – including a sewage-treatment plant with a daily capacity of 40,000 cubic metres. LJIP also provides a full range of supporting services for companies entering the park, such as assisting in processing enterprises’ registration and import/export procedures, and even referring factory design and construction agencies to them in order to ensure their smooth development in the park.

By the end of 2016, 36 companies had established a presence in LJIP, occupying 75% of its usable land. About 70% of these are mainland Chinese companies primarily engaged in the production and processing of metal products, agricultural products, foodstuffs, grain and oil, and packing and industrial materials. There are also investors from Japan, Korea, Singapore, Malaysia and Taiwan involved in production projects. Moreover, a number of Hong Kong-incorporated companies have also invested in setting up factories in LJIP to produce textile fibres, polyurethane materials, edible sausage casings, and knitted garments. The annual total output value of the companies operating in LJIP was estimated at US$470 million in 2016.

Tax and Cost Advantages

Companies operating in LJIP are entitled to corporate income tax concessions for up to 15 years. Furthermore, companies engaging in export processing can enjoy import-related preferential tax policies, which include exemption of import tariffs and value-added tax on materials imported for processing and production of products for export purposes. This preferential policy also applies to the import of related production machinery and equipment. [1]

Corporate Income Tax Concessions for Investments in Industrial Parks in Vietnam

- Current standard tax rate: 20% (since 1 January 2016)

- Tax concessions:

- Preferential tax rate at 10% for the first 15 years; plus

- Tax holiday for four years (counting from the first profit-making year), and

- 50% reduction in corporate income tax rate for subsequent nine years

It is understood that a number of companies currently operating in LJIP are mainly engaged in export processing, with some of the consumer goods produced exported to markets in Europe, the US and Asia. However, more are engaged in producing industrial materials or intermediate goods, which are supplied to downstream manufacturers in mainland China and Southeast Asia. Some of these products are sold to other manufacturers in Vietnam for further production and export. As such processing activities primarily rely on various kinds of imported raw materials, the exemption of import tariffs offered by the Vietnamese government is of prime importance to these manufacturers.

The convenient transport network and highly efficient logistics services available in LJIP also help enterprises enhance operation efficiency and lower production costs. LJIP is linked to Ho

Chi Minh City, only about 50km away, by the HCM City-Trung Luong Highway [2], which also connects directly to Saigon seaport, Hiep Phuos seaport (also about 50km from LJIP) and Bourbon port (about 35km from LJIP). This road link greatly facilitates the transportation of goods for import and export.

Labour Supply and Upstream Supporting Industries

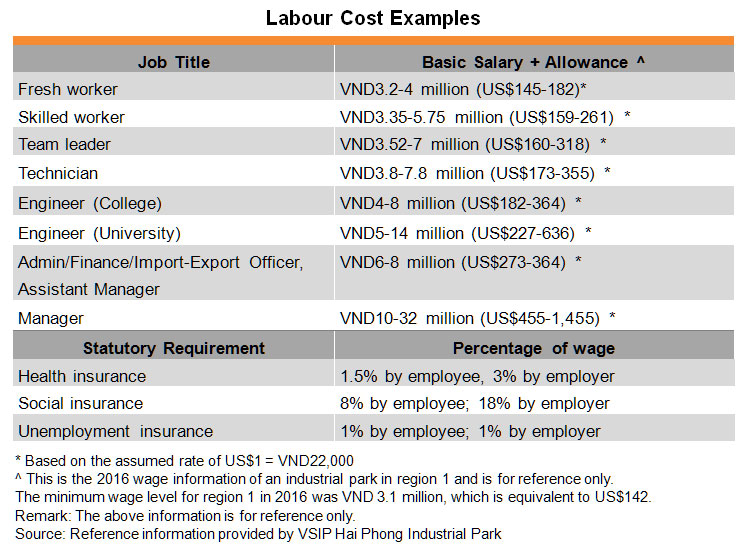

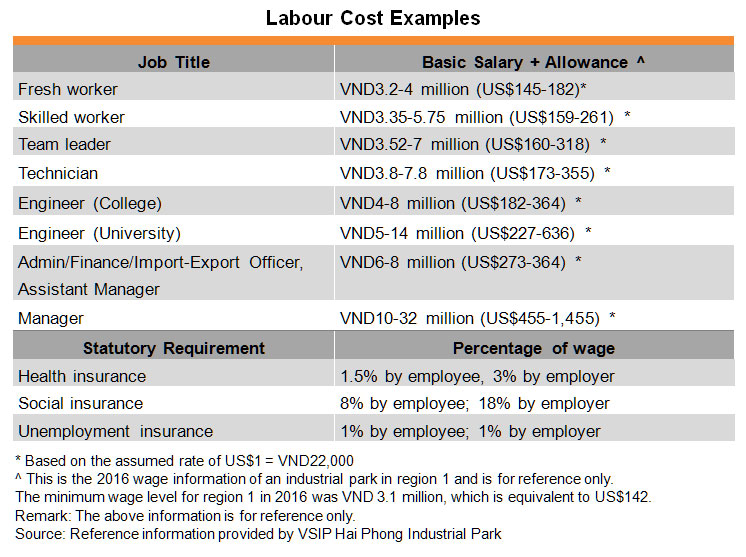

Companies aiming to invest in establishing factories in Vietnam have to choose the right industrial park and take note of the country’s overall investment environment, especially where labour supply is concerned. The minimum wage in Vietnam is currently less than US$200 per month. However, with the various mandatory fees, such as statutory social security and medical insurance, as well as higher salaries for more experienced and qualified employees, the actual labour costs borne by the employer start from about US$200-250 per worker per month.

While this minimum-wage level is lower than in many regions in China, and while the majority of workers in Vietnam are aged under 35, the workforce available in the local area is mainly made up of farmers, according to LJIP, most of whom lack experience working in modern factories. Moreover, Tien Giang Province itself is in short supply of skilled labourers and technical personnel.

According to statistics compiled by the General Statistics Office of Vietnam, nearly 80% of Vietnam’s labour force have not received any formal education, only 9% are university graduates and 11% have received secondary education or vocational training. Besides, only 21% of the people in employment in the country have received more than three months’ technical training, with the majority of them being classified as non-skilled workers. [3] Hence, manufacturers investing in Vietnam wishing to carry out more sophisticated production processes or conduct semi-automated or fully automated production may have to rely on the Chinese mainland or other neighbouring regions to provide various kinds of support in management, training and technology to their factories in Vietnam.

Moreover, Vietnam lacks support industries and falls short of various kinds of industrial raw materials and upstream production materials, as well as equipment and moulds for processing and production. The Vietnamese government has said it would introduce incentive policies and offer funds to nurture support industries, but even by 2020 these industries will only be able to meet 45% of local production demand. [4]

Vietnam is also short of technical design and engineering personnel, posing challenges to companies investing in R&D in the country in a bid to enhance their capability to design and manufacture the necessary production equipment. Most of the manufacturers currently investing in LJIP have to handle the import and export of production materials and finished products themselves, and at the same time take note of whether their investment projects are able to access effective technical support.

|

Hong Kong Enterprises Count on South China to Support Production Activities in Vietnam The operator of a Hong Kong enterprise engaged in plastics injection, metal stamping and die casting business in Hai Phong in northern Vietnam told HKTDC Research that he followed his foreign downstream clients to invest in the country and set up a factory there. He hopes the company can reduce the time required to deliver products to this downstream clients and, at the same time, enjoy the tax benefits offered by Vietnam. According to this Hong Kong enterprise, however, operating in the production field in Vietnam involves various challenges – notably, that local workers tend to be untrained with lower productivity than their counterparts in South China. Although labour costs in Vietnam are lower, the cost differential between the workforce of Vietnam and China becomes insignificant when productivity is taken into consideration. In order to enhance production efficiency, the company plans to introduce further automation in its factory and reduce the use of labour. In this way, labour costs will become a less-important factor in the consideration of investment plans. However, there is a lack of support industries, such as sophisticated mould manufacturing and technical backup, in Vietnam. Coupled with its lack of technicians and engineers, the Hong Kong company could hardly embark on its own mould and tool manufacturing business there. Instead, it has had to seek various kinds of supporting services and material supply from mainland China. On the one hand, it had to co-ordinate the deployment of in-house technical personnel and other production facilities such as Computer Numerical Control machinery so as to have the moulds and production tools manufactured in South China for delivery to Vietnam for subsequent processing. On the other hand, the company had to rely on efficient logistics services to have the plastic and metal materials for production transported to Vietnam as they mainly came from China and other Asian countries. The company, therefore, had to count on China for various kinds of support services in order to follow in the footsteps of its downstream clients to invest in Vietnam. |

Policy Risks

According to LJIP and relevant government departments of Vietnam, where attracting foreign investment is concerned Vietnam continues to welcome mainland Chinese enterprises. However, given the intricacies of international politics and sporadic outbursts of anti-Chinese sentiment, mainland investors must ensure that their operations comply with Vietnamese laws and regulations, as well as local conditions, so as to avoid unnecessary misunderstandings and problems.

Of particular note is that compared with developed countries in Europe and the US, Vietnam still does not have a sound legal system in line with international standards. Its laws and regulations governing foreign investment have much room for improvement and the government departments concerned do not have enough experience in dealing with more complicated foreign investments.

Although this may not affect the examination and approval process for investment projects, it is possible that the government may introduce retrospective restrictions and even demand re-negotiation of investment projects to ensure they are suited to local conditions and do not pose a threat to certain industries or sectors. This could have an adverse impact on the investor’s budget, which in turn undermines the sustainability of the project.

For instance, Vietnamese people are becoming increasingly concerned about industrial pollution, and the government is placing more emphasis on environmental protection in the course of attracting foreign investment. The issue of pollution is particularly sensitive in the rural areas, where protests are becoming more frequent.

In recent years, Vietnam has promulgated a number of national emissions standards aimed at restricting the discharge of pollutants by different economic entities. Since the country’s new Environmental Protection Law came into effect in 2014, many industrial projects are required to undergo environmental impact assessments, while production activities carried out in economic zones and industrial parks must meet the relevant environmental and emissions standards. Meanwhile, LJIP has stated that all companies entering the park must comply with the relevant environmental regulations, and that any acts of unlawful emissions or unauthorised disposal of wastes are strictly prohibited. [5]

When companies set out to plan their investments, action must be taken to ensure that their projects pass the environmental impact assessment and meet the emissions regulations stipulated by the local authorities. They should also gain a good understanding of the actual environment where their investment is located and consider the reactions of local residents.

Where necessary, companies should take the initiative and offer opinions to its investment partners and local government authorities on how it will meet the relevant international environmental standards. By so doing, both parties can thoroughly assess the environmental requirements of the project at the initial planning stage, and conduct consultations to achieve a win-win investment plan rather than simply meet the minimum legal requirements.

What’s more, since mainland enterprises tend to give people a negative impression where environmental protection is concerned, they must strengthen environmental due diligence and observe Vietnam’s laws and regulations as well as local conditions so as to avoid unnecessary hiccups.

Investors should also keep an eye on Vietnam’s foreign-investment policies and its changing business environment to ensure the sustainable development of their investment projects. For instance, when Vietnam opened up to the outside world at the end of the last century, great efforts were made to attract foreign investment in labour-intensive and low value-added industries.

In recent years, however, some foreign investors, including multinational companies from Japan, Korea and Taiwan, have begun to invest in production activities with higher technology content in Vietnam. While such investments mostly involve export processing, the Vietnamese government has on various occasions indicated that, in order to promote industrial modernisation, it hopes to encourage foreign investors to invest in high value-added and high-tech industries, while avoiding obsolete technologies and highly polluting production.

In view of this, when investors formulate their investment plans, they must take into consideration the possible changes that may occur in Vietnam’s industrial sector in the short to medium term instead of focusing on its current or past policies on foreign investment, so that their projects can take advantage of the relevant preferential policies and other industrial support.

In order to plan their projects, investors in Vietnam may refer to the government’s long-term development blueprint for guidance in areas such as the connection between private and public facilities, logistics arrangements and integrated supply chain planning. For example, LJIP is actively upgrading the road system within the park to help take advantage of the HCM City-Trung Luong Highway. It has also expedited negotiation with the local government in the hope of advancing the construction of roads in the park connecting with the highway in a move to enhance the overall transportation and logistics efficiency of the park.

|

Risk Management of Belt and Road Investment China has investments all over Europe, the Americas and Asia. However, as China gradually extends its outbound investment to countries along the Belt and Road routes, enterprises “going out” may face higher investment risks because the legal environment leaves something to be desired in some of these countries. Strong professional support is clearly imperative. Betty Tam, a Partner of Hong Kong law firm Mayer Brown JSM, said, “Some of the countries along the Belt and Road routes are not popular recipients of foreign investment, and some have not set up any sound legal systems in line with international standards nor any laws and regulations governing foreign investment. “Through their extensive international networks, Hong Kong legal practitioners can act as team leaders of international projects and lead the professionals of different countries. “They also have access to experts with local experience who can help conduct due-diligence investigations for Belt and Road investment projects and offer customised strategic proposals and feasibility reports that suit the actual situations of different places of investment. Hong Kong’s service platform boasts a mix of advantages, such as free movement of funds and a simple and low-rate tax system. “Together with Hong Kong’s efficient business environment, this platform can facilitate investors in setting up companies for special purpose, restructuring their M&A transaction structure for future holding, transfer or alienation of equity or asset in the target company, and help carry out financing and handle cross-border tax arrangements for the projects concerned. It can provide mainland investors with one-stop professional services and assist them in capturing opportunities arising from the Belt and Road Initiative.” Notes: (1) For further details, please see HKTDC research article (July 2016): |

Investors that have thoroughly evaluated all aspects of their projects at the initial planning stages can not only better ensure their competitiveness but also enjoy the policy concessions and facilitation offered by Vietnam in support of local development. They can also avoid the prospect of having to re-negotiate with the government at a later stage. Nevertheless, Vietnam still has to resolve many administrative and bureaucratic issues. If an investment project lacks thorough planning resulting in a grey area, such administrative issues could bring problems when the investor negotiates with the government at a later stage, which will in turn incur extra costs in terms of money and time on the part of the investor. Although the government has pledged to deal with these problems and improve administrative efficiency, such difficulties are expected to remain in the short term.

Hong Kong’s professional service providers can make use of their extensive international networks to obtain information on Vietnam and details about investment projects in the country.

Apart from studying the background and data of these projects, they can also make professional assessments of the prospects of investing in Vietnam, offer detailed analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of proposed investment plans, provide accurate future performance and risk forecasts, and make all-round strategic investment recommendations.

As far as environmental protection is concerned, Hong Kong also has a pool of service providers rich in international experience, which can offer custom-made solutions to mainland enterprises for their investment projects in Vietnam. These solutions can meet the needs of the investor and comply with local laws and regulations.

Please click here to purchase the full research report.

[1] For more details, please see HKTDC research article (March 2017): Vietnam Utilises Preferential Zones as a Means of Offsetting Investment Costs

[2] Opened to traffic in 2010, the 62km HCM City-Trung Luong Highway connects Ho Chi Minh City with Tien Giang Province and other areas in the Mekong River Delta region

[3] For more details on labour costs, please see HKTDC research article (April 2017): Vietnam’s Youthful Labour Force in Need of Production Services

[4] Source: Vietnam’s Master Plan on Supporting Industry Development to 2020, Vision to 2030

[5] For more details, please see HKTDC research article (April 2017): Vietnam’s Increasing Demand for Environmental Services

Belt and Road: Development of China’s Overseas Economic and Trade Co-operation Zones (1)

Belt and Road: Development of China’s Overseas Economic and Trade Co-operation Zones (3)

Belt and Road: Development of China’s Overseas Economic and Trade Co-operation Zones (4)

Belt and Road: Development of China’s Overseas Economic and Trade Co-operation Zones (5)

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Guangxi has a 1,020km border, with three prefecture-level cities adjoining Vietnam. Its border region is one of the four areas for development under the strategy of the “four alongs” currently being implemented in Guangxi. Apart from border trade, which plays an important role in the autonomous region, Guangxi is also promoting cross-border economic co-operation to open up and develop the areas along the border. Border platforms such as cross-border economic co-operation zones and key experimental zones for development and opening up will gradually become the important carriers for opening up and co-operation between Guangxi and ASEAN countries. Moreover, Guangxi plans to develop border processing industries in the ports along the border and promote the transformation of border trade from “cross-border transit” to “inbound processing” while strengthening its trade distribution functions.

Important Role of Border Trade

ASEAN is the principal trading partner of Guangxi, topping its trading partner list for 16 years in a row. In 2016, Guangxi’s import and export value with the ASEAN region accounted for 65% of its provincial total. Guangxi’s trade with Vietnam across its border made up 60% of its total trade value in 2016. Commodities in its export list mainly comprise electrical and mechanical products, textiles, garments, agricultural products, ceramic products, vegetables and footwear, whereas its import list covers agricultural products, electrical and mechanical products, fruits, grains, feeds and coal.

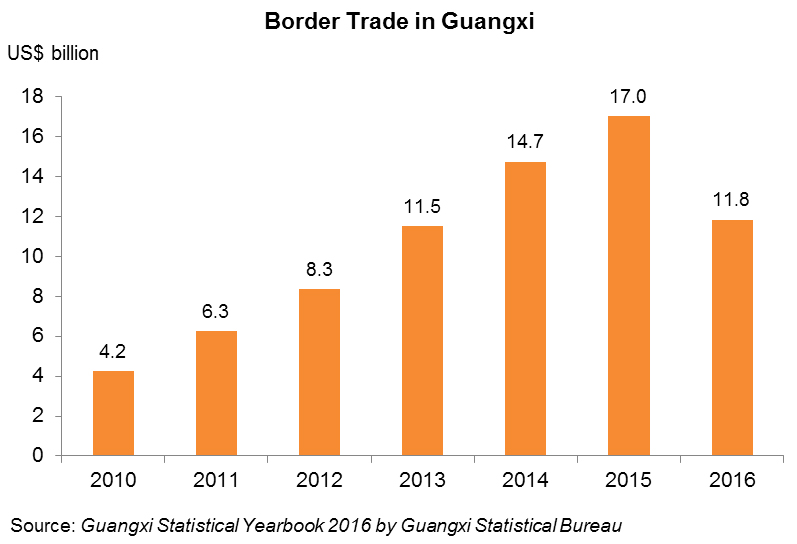

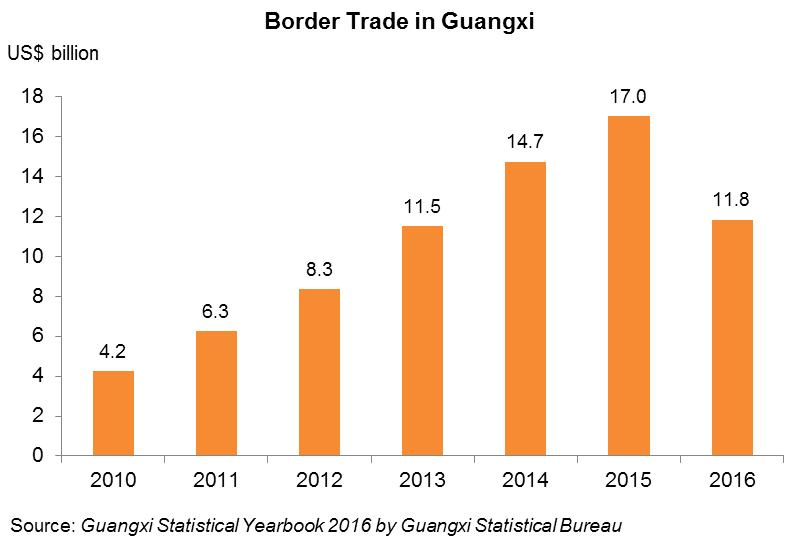

There are 12 border ports and 26 border trading posts in Guangxi. Border trade [1] has been thriving in the autonomous region, constituting 34% of its total trade value in 2014, although the figure dropped to 25% in 2016. These trading activities are mainly conducted with Vietnam, accounting for more than 50% of the total trade value between Guangxi and Vietnam. In respect of Guangxi, more than 90% of its total border trade value comes from exports.

The total border trade value of Guangxi ranks first among all border provinces and regions in China. Export items of its border trade are dominated by electrical and mechanical products and textiles, such as motorcycles, auto parts, small hardware as well as men’s and women’s tops, which constitute some 70% of the total export value of its border trade. Import items mainly consist of agricultural products and mineral products, such as anthracite and minerals of titanium, iron, zinc and aluminium, tropical fruits, mahogany and wood products, which account for about 80% of the total import value of Guangxi’s border trade.

Of all of China’s border ports, Dongxing Port has the highest volume of cross-border passenger traffic. Many Chinese domestic products are exported to ASEAN countries through these border ports, through which products from Vietnam are imported to China. While the port of Friendship Pass is the distribution centre of mahogany products, Dongxing Port has become a distribution centre for marine product processing, and Shuikou is the principal port for nut imports from Vietnam and ASEAN countries.

Development of Border Trade and Processing Industry

In 2016, the State Council of China published the Opinions on Several Policy Measures in Support of the Development and Opening Up of Key Border Regions, which spells out its support for the development of strategic regions along the borders, including pilot zones for strategic development and opening up, national-level border ports, border cities, border economic co-operation zones and cross-border economic co-operation zones. The document mentions that these border regions are becoming the pioneers of China’s implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative. Guangxi has, in fact, started to push forward some border development policies in recent years prior to the publication of the above document.

According to the Memorandum of Understanding on Development of Cross-Border Co-operation Zones signed between China and Vietnam in 2013, there will be three China-Vietnam cross-border co-operation zones in the first batch of development projects, one at the China-Vietnam border of Hekou-Lao Cai in Yunnan province, and two at the China-Vietnam border of Dongxing-Mong Cai and Pingxiang-Dong Dang, both in Guangxi. For the Joint Master Plan on China-Vietnam Cross-Border Economic Co-operation Zones, China has already submitted its draft to Vietnam whereas Vietnam has devised its own draft. Working in collaboration, they will study both drafts and finalise a joint master plan.

Focusing on the development of its border economic belt, Guangxi strives to promote industrial co-operation along the border as well as cross-border interconnection and intercommunication. Border platforms such as economic co-operation zones and national pilot zones for strategic development and opening up will gradually become important carriers for opening up and co-operation between Guangxi and ASEAN countries.

At present, Guangxi is developing the processing industry in border ports while promoting the transformation of border trade from “cross-border transit” to “inbound processing”. It also strives to speed up the development of the cross-border economic co-operation zones of Dongxing-Mong Cai and Pingxiang-Dong Dang along the China-Vietnam border. Permission has been given for border regions such as Dongxing and Pingxiang to expand their pilot zones for cross-border labour co-operation so that its border processing industry can capitalise on Vietnam’s labour force.

Border trade has become the principal form of China-ASEAN commodity trade conducted by small- and medium-sized companies of Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar and Thailand. While some products imported from Vietnam come from other regions, suppliers from other mainland provinces and regions are also attracted to export their products to Vietnam or re-export to other ASEAN countries through the border trade in Guangxi. It is estimated that 80% of Guangxi’s border import trade involves re-sales to other mainland regions. In view of this, apart from promoting a border processing industry, Guangxi plans to build up a more extensive market distribution function. For example, Pingxiang is planning to expand its specialised fruit distribution market.

Pilot Zones for Development and Opening Up Boost Growth of Border Regions

Upon the approval of the State Council, two key pilot zones for development and opening up have been set up along the border in Guangxi – the Dongxing Key Pilot Zone for Development and Opening Up officially established in 2014, and the Pingxiang Key Pilot Zone for Development and Opening Up approved in August 2016.

The Pingxiang Key Pilot Zone for Development and Opening Up has a planned area of 2,028 sq km with Pingxiang City as its core supported by six major functional zones, namely, an international economic, trade and commercial zone; an investment co-operation development zone; a key border economic zone; a cultural and tourism co-operation zone; a modern agricultural co-operation zone; and a border city pioneer development zone.

The Dongxing Key Pilot Zone for Development and Opening Up covers Dongxing City and the port district with a total area of 1,226 sq km. Dongxing City, under the administration of Fangchenggang Municipality, is just across the river from Mong Cai City in Vietnam. The daily passenger traffic of Dongxing port is about 20,000 to 30,000, and its annual total reached 7.15 million in 2016.

Capitalising on the platforms of the Dongxing Key Pilot Zone for Development and Opening Up, the Dongxing China-Vietnam Cross-Border Economic Co-operation Zone inside the Key Pilot Zone, as well as the Financial Reform Pilot Zone along the border, Dongxing is poised to develop six major cross-border industries. The six are: cross-border trade, cross-border tourism, cross-border processing, cross-border e-commerce, cross-border finance and cross-border logistics, all aim at serving Vietnam. Specifically, cross-border trade will focus on mutual trading activities between border residents of both countries; cross-border processing will concentrate on marine products and agricultural by-products, as well as the deep processing of mahogany (four mahogany markets have already been set up in Dongxing) to form distribution centres of related products; and cross-border e-commerce aims to promote the integrated development of border trade and e-commerce, particularly in respect of agricultural by-products.

The Dongxing Key Pilot Zone for Development and Opening Up is mainly characterised by its policy of introducing “early and pilot” measures. The Pilot Zone can explore different policy innovations, including the forms of opening-up and co-operation, as well as financial and tax management models. All innovative policies of opening up, co-operation and reform, such as those on customs facilitation, China-Vietnam integrated border control, and cross-border labour administration, are possible areas for exploration by the Pilot Zone.

One of the major tasks of the Dongxing Key Pilot Zone for Development and Opening Up is to develop a cross-border economic co-operation zone at the China-Vietnam border of Dongxing on both sides of the Beilun River. A core zone of 10 sq km has been planned for Dongxing on the China side, whereas the park zone on the Vietnam side covers 13.5 sq km, with a bridge connecting both sides. The co-operation zone will be operated in the forms of “shop in front and factory at the rear”, “two countries, one zone”, “within and beyond the border”, and “closed border operation”. Planned to “open at the first line and control at the second line”, the zone will pursue the closed operation model of a cross-border free-trade zone within which people, goods and vehicles of both sides can flow freely.

Infrastructural facilities on the Chinese side of the co-operation zone are basically complete, as is the bridge to link the two sides of the zone. The official commencement date of closed operation of the zone has yet to be finalised. The Chinese part of the zone will be developed into three districts. The first is a financial, commercial, trading and tourism district covering 2.06 sq km. The second, with an area of five sq km, is a garment and agricultural by-product industrial district for processing trade, and the third is a logistics and warehouse district. Construction of the first district has been topped out to provide, inter alia, an ASEAN attractions street, and is expected to open to all visitors with identification documents. The daily duty-free limit is RMB8,000 per visitor.

Nine standard factory blocks with a total floor area of more than 60,000 sq m will be completed in the processing trade district by the second half of 2017. Two standard factory blocks have already been constructed, and a mobile-phone assembly plant has moved in for operation. Its finished products are to be exported to Vietnam, while those processed with raw materials from Vietnam will be sold to the Chinese mainland. As the zone will make use of the Vietnamese workforce, the next step is to regulate and quantify the cross-border use of workers with the establishment of a labour management centre.

On the Vietnam side, it is understood that the planning and design blueprint has been completed. In the Dongxing area, there will be a core zone and a number of supporting zones such as an industrial park, a logistics park and a border trade centre. Inside the Jiangping Industrial Park, there are already more than 100 enterprises operating.

With the current direction of development, the cross-border economic co-operation zone and supporting zones can enhance Dongxing’s commercial and trade functions, including commercial services for external trade, commodity exhibition and sale, warehousing, transportation and tourism, helping to shape the city as China’s comprehensive trade centre targeted at Vietnam and entrusted with the integrated functions of processing production, purchasing and transit transportation. Hong Kong companies interested in capitalising on the border policies of China to capture ASEAN market opportunities should take note of the development of these commercial and trade functions.

[1] Border trade refers to the import and export trading activities conducted at designated land border ports between enterprises registered in Guangxi and approved by the government departments of foreign trade and economic co-operation/commerce with border trade operator qualification, and the enterprises or other trade organisations of neighbouring countries of Guangxi or countries adjoining its border.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

The lower labour costs, improved infrastructure and preferential tax treatment have all led to Vietnam attracting a significant inflow of foreign direct investment (FDI). Increasingly, the country is now targetting investment from higher value-added industries, with potential investors advised to look beyond labour cost advantages. There are, however, genuine concerns as to the lack of engineering expertise and ancillary industries within the country, a particular challenge for any business undertaking more sophisticated production with higher degree of automation.

In order to tackle this shortfall, certain investors – including a number from Hong Kong, are making use of the technical and other services, as well as material supplies from the Chinese mainland as a means of supporting their Vietnamese operations. Even for the infrastructural development, such as those in Northern Vietnam bordering China, one of Vietnam’s development directions is to strengthen the country’s access to the Chinese supply chain. In the circumstances, effective management and efficient logistics services are crucial when it comes to ensuring foreign investors and other related companies can properly orchestrate their cross-border arrangements and achieve the maximum operational efficiency.

Enhancing the Infrastructure of Northern Vietnam

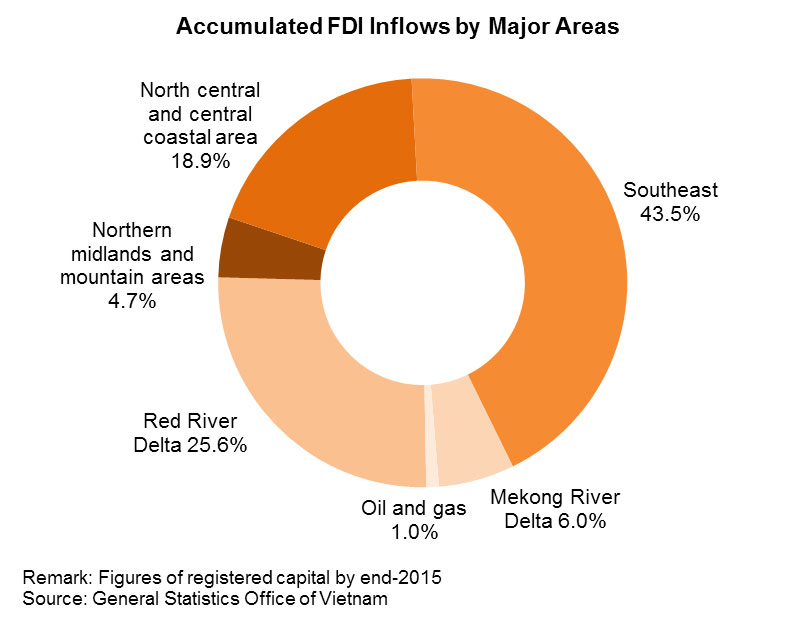

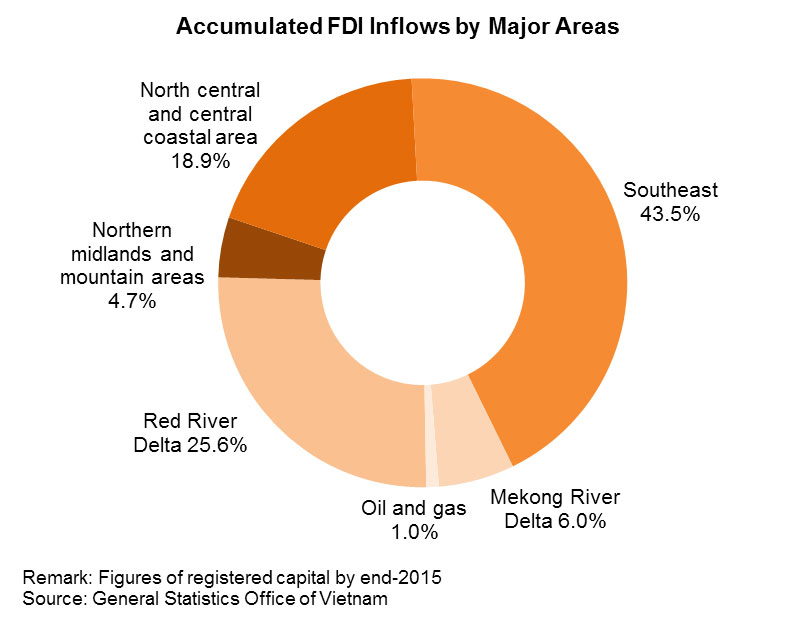

Northern Vietnam is being increasingly targetted by foreign investors, many of whom had previously favoured business opportunities in the south of the county. Highlighting this traditional preference, at the end of 2015, the southeast part of the country – extending across Ho Chi Minh City, Dong Nai and Ba Ria-Vung Tau – accounted for 43.5% of the total accumulated FDI inflow. By comparison, the Red River Delta – including Hanoi, Bac Ninh and Hai Phong – accounted for just 25.6% of the cumulative total. More recently, nonetheless, the northern cities and provinces have started to attract a greater proportion of overall FDI. This is down to both a greater effort on the part of the government to promote the economy of the north and a marked improvement to the infrastructure across the region.

A sign of this change in emphasis is the city of Hai Phong, which attracted the second highest level of FDI in Vietnam in 2016, solely trailing Ho Chi Minh City. Hai Phong is set within the Hanoi-Hai Phong-Ha Long economic triangle. It is also the site of Northern Vietnam’s largest seaport. Of late, sea freight connections between Hai Phong and the ASEAN, US and European markets have been bolstered by the increased availability of container liner services, the consequence of a shift in focus by the international shipping companies.

Cat Bi International Airport, Hai Phong’s principal air transportation hub, has direct links to several other Vietnamese regions, including Ho Chi Minh and Da Nang, as well as offering flights to other Asian countries. The completion of a new highway connecting the city to Hanoi, the country’s capital, has also provided a boost to business and industrial activities in the Hai Phong region. The highway also extends to Ha Long, capital city of the resource-rich Quảng Ninh province. Additionally, Hai Phong’s access to the markets and supply chains of southwest China have been further improved by the completion of highway connections to Mong Cai and Lang Son, the two Vietnamese cities that respectively border the Chinese townships of Tongxing and Pingxiang of Guangxi region.

Hai Phong: The Cost Benefits

Overall, the improvements to its infrastructure have made Hai Phong far more attractive to a range of business and industrial investors, with the success of the VSIP Hai Phong Industrial Park being an example of this. Jointly established in 2008 by a Singapore consortium and a Vietnamese state-owned enterprise, it has a total area of 1,600 hectares, of which 500 hectares are reserved for industrial development. The remaining space has been given over to a range of commercial and residential projects.

As well as benefitting from improvements to the local transportation network, VSIP Hai Phong also owes much to its success to its access to all the required utilities, including reliable electricity, water supplies and optical fibre telecommunication services. This has seen it attract projects largely related to higher value-added industries. To date, these include companies specialising in:

- Electrical and electronics

- Precision engineering

- Pharmaceuticals and healthcare

- Supporting industries

- Consumer goods

- Building and specialty materials

- Logistics and warehousing

In line with the latest government regulations, industrial investors in VSIP Hai Phong are entitled to claim a range of tax benefits, including preferential corporate income tax rates and exemption from certain import taxes (those related to export processing enterprises[1]). Employees working in the park also pay a lower level of personal import tax[2]. In addition to this, labour costs are relatively low in Hai Phong and its neighbouring regions, with the total monthly cost per worker – factoring in statutory contributions, such as insurance – starting at around US$200-250. This is a relatively low cost when compared to the current wage levels in China.

(Remark: For more information regarding labour costs, please see: Vietnam’s Youthful Labour Force in Need of Production Services.)

Seeking Production Supports from China

According to VSIP Hai Phong, the park is currently home to some 35 industrial projects, with investments sourced from ASEAN, Japan, Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong. An estimated 70% of its industrial areas have already been occupied by such projects. For the future, the park plans to attract more high-end investments, specifically those related to production of technology products and the supporting industries. Any such investments, of course, will be obliged to comply with all the statutory environmental regulations, although any potentially polluting industry that demonstrates it can meet the required emission standards may not be refused.

Many of the industrial projects based in the park are related to processing production, particularly with regard to textiles and clothing items, electronic products and packaging materials. Among the other investors are several companies engaged in the manufacture of intermediate goods, the majority of which are utilised as production inputs by downstream clients in Hai Phong and Northern Vietnam. Production of this kind, however, relies heavily on imported industrial goods and raw materials. One foreign-invested company, which undertakes the assembly production of electronic products and office machinery, for instance, has indicated that it is sourcing competitively-priced, high quality parts and components from elsewhere in Asia in order to support its Hai Phong production activities.

Several Hong Kong-invested companies are also operating in VSIP Hai Phong. One of them, which has a focus on plastic injection moulding, metal stamping and die-casting, told HKTDC Research that it had established a manufacturing operation in Vietnam in order to follow in the footsteps of one its downstream clients. Typically, the plastic and metal outputs of its Hai Phong factory are mainly used for the processing production of IT and other electronic products by its clients in Vietnam. As such, maintaining the Hai Phong factory saves the company money when it comes to logistics costs, while shortening the delivery lead time to its downstream clients. As another plus point, it also enjoys the accrued tax benefits of being based in Vietnam.

While acknowledging a number of clear advantages of being based in Vietnam, maintaining an operation in Hai Phong has not been without its challenges for the company. One of its particular problems is related to the relatively low skill levels of many local workers, with their productivity, consequently, a bit lower than that of their counterparts in southern China. While Vietnamese labour costs are lower, in productivity terms, the labour cost differential between Vietnam and China is far from substantial. In order to enhance its production efficiency, the company is now planning to further automate its operations, a development that will see it requiring lower staff levels. Labour costs, therefore, will ultimately become relatively insignificant when it comes to considering further investments at the site.

The fact that Vietnam lacks a number of the key supporting industries, such as precision tool-making and engineering support, has huge significance for the future industrial development of the country. This lack of technicians and engineers, for instance, has already deterred the aforementioned Hong Kong company from establishing an in-house manufacturing moulds and tooling facility in Hai Phong.

In order to tackle these problems, the company has to buy in various services and supplies from the Chinese mainland. For one thing, the company needs to orchestrate their in-house engineering talents and facilities like computer numeric control machines to make the moulds and tooling in south China, which would then be shipped to Hai Phong for use in processing production. As the plastics and metal raw materials are mainly sourced from China, as well as certain other Asian countries, the company is obliged to utilise efficient logistic services for the delivery of such materials to Hai Phong. The company, then, is making the best use of a variety of supports from China in order to facilitate its bid follow its client’s downstream investments in Vietnam.

[1] For details of the preferential treatment, please see: Vietnam Utilises Preferential Zones as a Means of Offsetting Investment Costs.

[2] According to VSIP Hai Phong, all local and expatriate labours working in Dinh Vu-Cat Hai Economic Zone (including VSIP Hai Phong) enjoy 50% reduction of personal income tax.