Poland

Central and Eastern European Countries (CEECs) have played an increasingly pivotal role in China’s foreign policy considerations and are key partners to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Cash-rich Chinese white knights have become highly sought-after by many struggling but promising CEE businesses, while generous funding for mega government-to-government (G-to-G) infrastructure projects and seed capital for start-ups are also providing valuable impetus to rejuvenate the CEE economy and restore its industrial and commercial prowess.

CEECs as a Key Partner to “16+1” and BRI

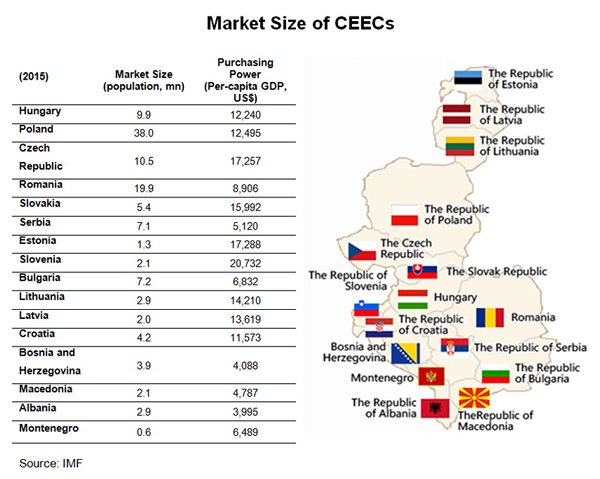

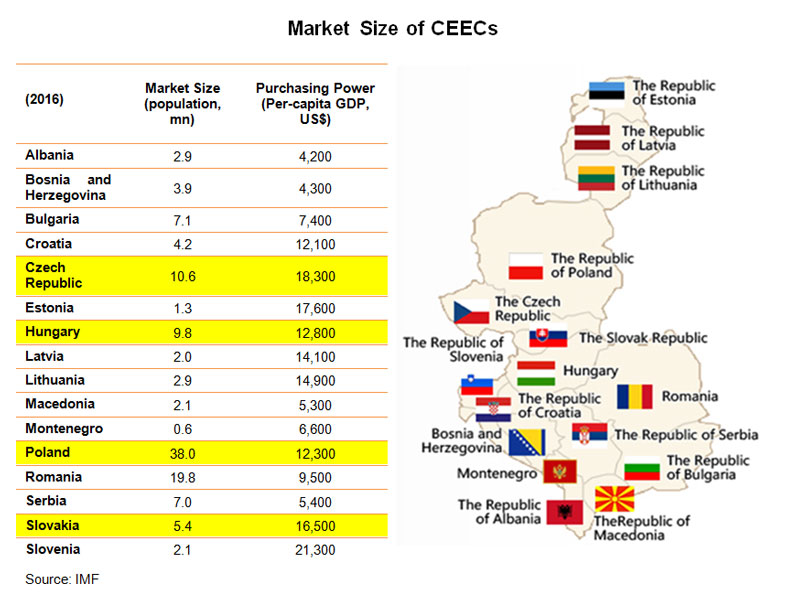

In 2011, China revived its co-operation with a group of 16 Central and Eastern European countries (CEECs), namely Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia and Slovenia. In 2012, the first meeting at a heads of government level was held in Warsaw, marking the official launch of the 16+1 format or mechanism under which China provides preferential financing to support investment projects that use Chinese inputs such as equipment “through business means”.

Since its establishment, the 16+1 format has not only been well-received by member countries, but is increasingly used as a leeway to allow cash-strapped CEECs to sidestep possible violations of EU restrictions on sovereign debt levels. Strengthening Sino-CEEC co-operation and connectivity is also conducive to the successful implementation of the BRI, which aims to facilitate and promote greater integration among the 60-plus countries along the Belt and Road. CEECs, providing a strategic link between Asia and West Europe, are vital to the success of the BRI.

Sino-CEEC Investment and Trade Continue to Blossom

Banking on good Sino-CEEC relations and China’s implementation of a “going out” strategy at the turn of the century, Chinese investors have been investing in projects across the CEECs for some time. China’s outbound direct investment (ODI) in CEECs has been flourishing, while bilateral trade has also blossomed.

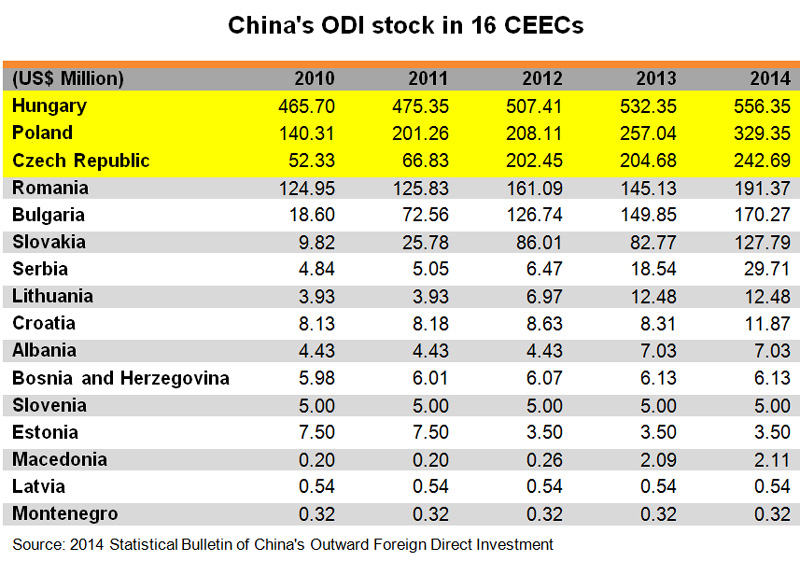

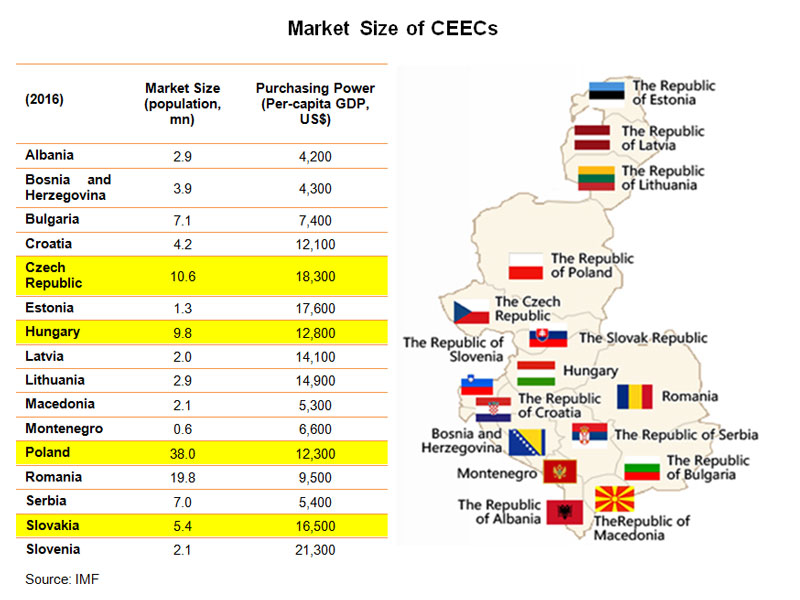

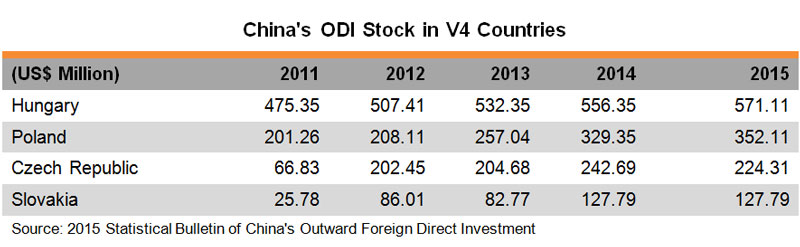

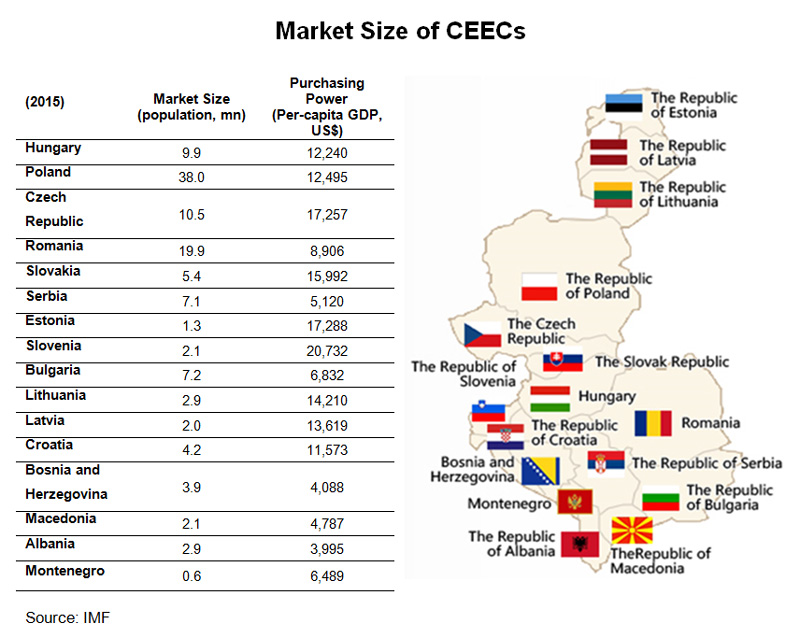

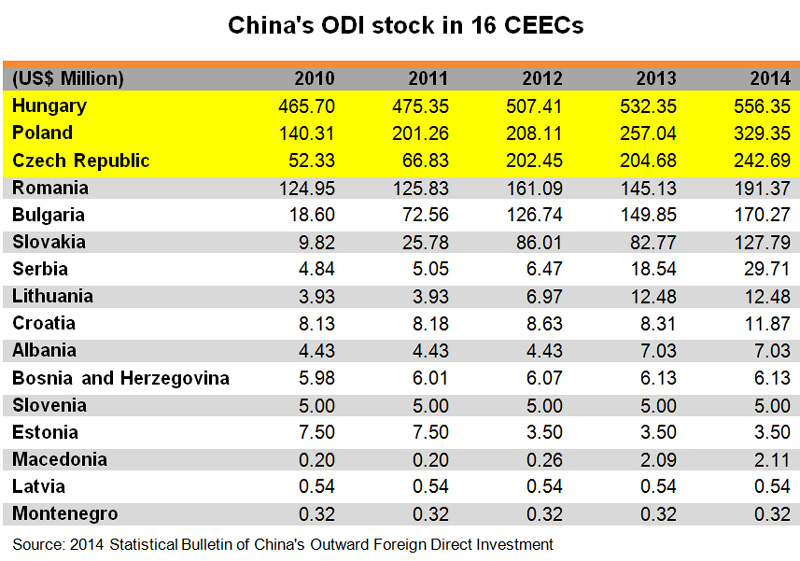

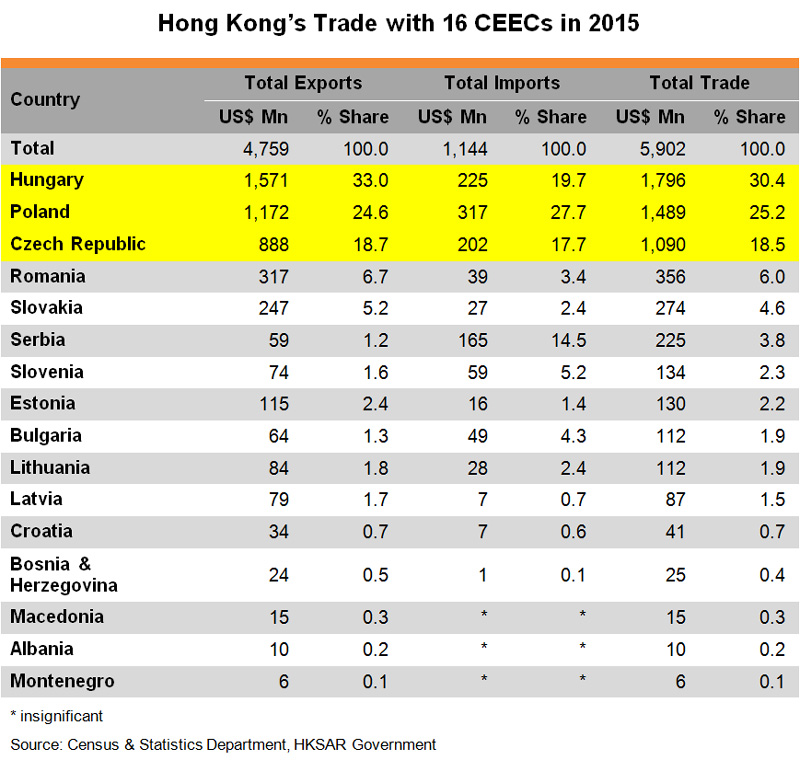

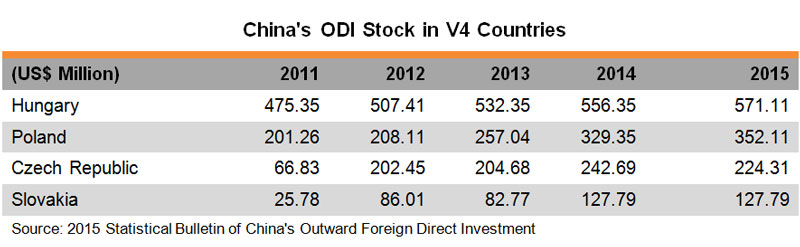

In the five years ending 2014, China’s ODI to CEECs grew by nearly 100% from US$853 million to US$1.7 billion. Among the 16 CEECs, three countries – namely Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic – accounted for more than two-thirds of the total, followed by Romania, Bulgaria and Slovakia, which together accounted for another 30%.

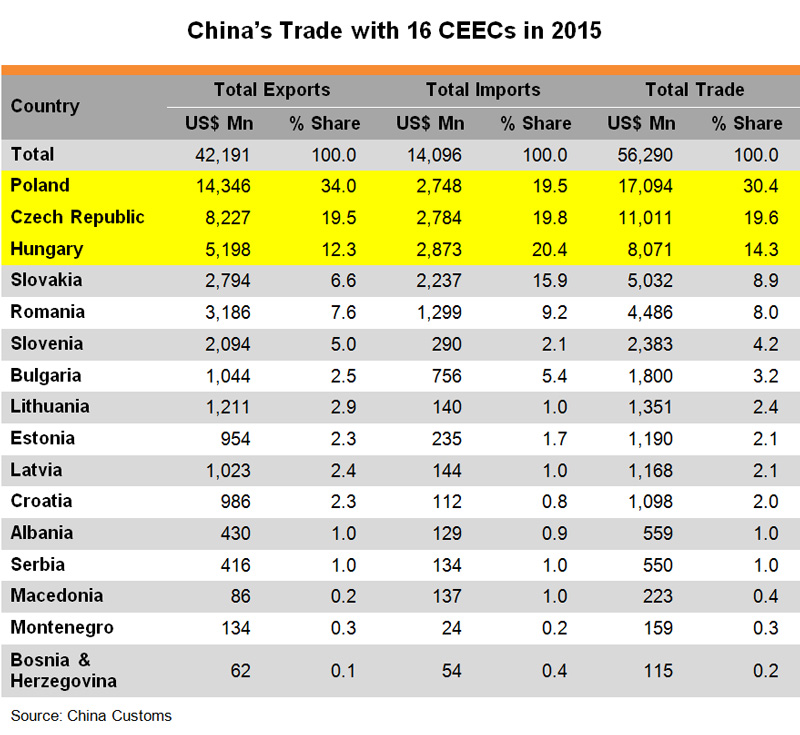

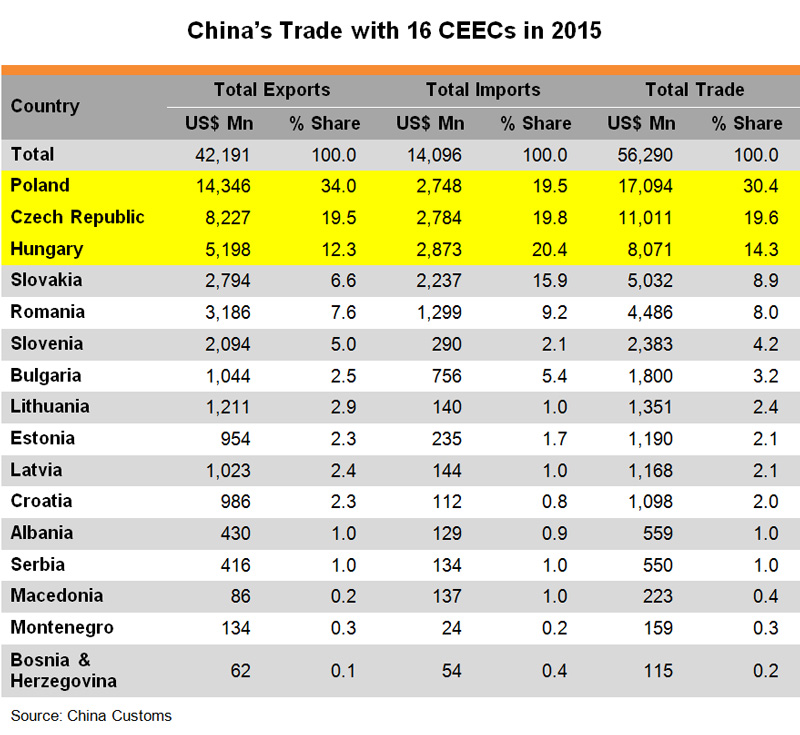

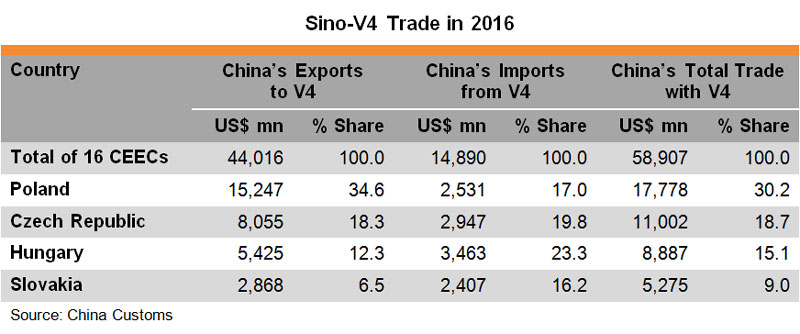

Trade between China and CEECs has remained unbalanced, however. In 2015, China’s exports were nearly twice the size of its imports from the 16 countries. This huge trade imbalance has provided a rallying cry for a new development model featuring enhanced connectivity with greater investment in infrastructure such as railroads, highways, tunnels, bridges, power plants, electric grids, industrial and logistic parks, seaports and airports.

In fact, there is already a balancing trend in Sino-CEEC trade, due mainly to an increase in demand for products such as metals, minerals, chemicals and food and beverages from CEECs. Between 2011 and 2015, China’s trade with 16 CEECs grew by a mere 6.4% from US$52.9 billion to US$56.3 billion. The country’s exports to CEECs increased in that period by only 5.0% but imports from the 16 countries saw a 10.5% expansion. Similar to the pattern seen in China’s ODI to CEECs, Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary were China’s top three trading partners among the 16 CEECs, accounting for more than 64% of all Sino-CEEC trade in 2015.

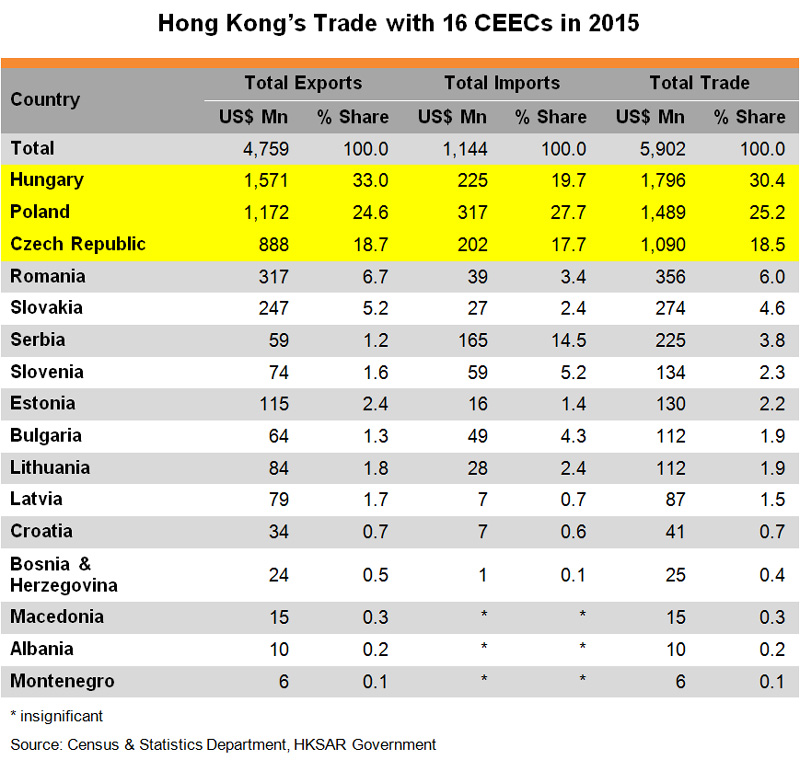

Though Hong Kong’s investment in the 16 CEECs is far from significant, its trade pattern is consistent with Sino-CEEC trade overall, with Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic accounting for nearly 75% of Hong Kong’s total trade with the 16 CEECs in 2015. Boasting a similar year-on-year growth of 24% in the first half of 2016, compared to the 13% regional average, Hungary and Poland are not only sizeable markets among the CEECs, but fast-growing export destinations for Hong Kong traders.

Looking ahead, better alignment of the 16+1 format with the BRI is expected to provide new opportunities to widen and deepen trade and investment co-operation between China and the CEECs. Moving from being export destinations to becoming investment partners in production, technology, finance and infrastructure development, CEECs are likely to see new trade patterns with China, involving higher value-added goods and services with higher technology content.

While different good and services may experience different fortunes in the CEECs, electronics – Hong Kong’s largest merchandise export earner – has fared well in the region. This is especially the case in countries where electronics manufacturing outsourcing clusters are becoming increasingly prominent in the face of rising production costs in other more distant production bases and in light of a greater need for proximity to key markets and better inventory management.

To this end, Hungary has been specialising in the production of transport vehicles since Soviet times, and boasts a long history of auto parts and electronics manufacturing. Hungary is the largest electronics producer among the CEECs, representing some 30% of the region’s total electronics output. Meanwhile, the Czech Republic is often regarded as the most successful Central and Eastern European country in terms of attracting foreign investment, thanks to its strong automotive cluster. For its part, Poland has the largest domestic market and ranks high in terms of manufacturing and automation.

Examples of BRI in Action in the CEECs

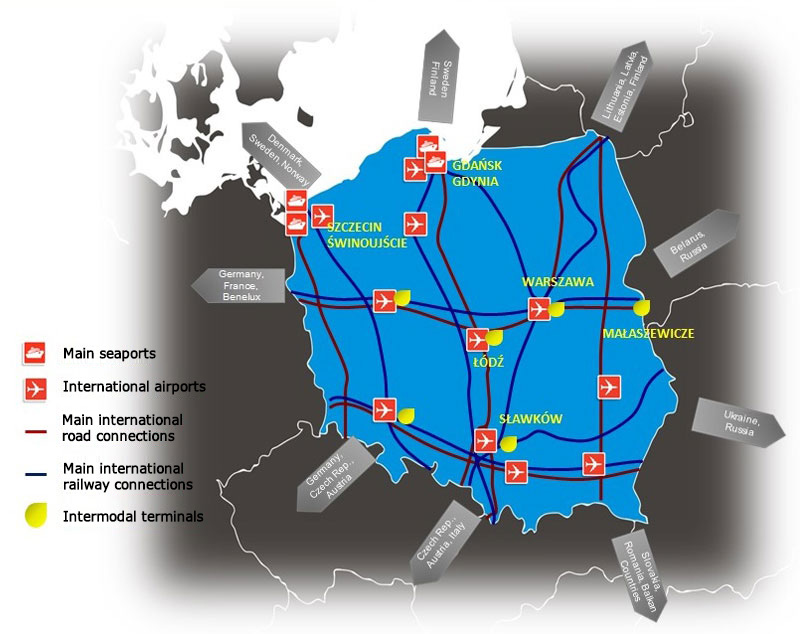

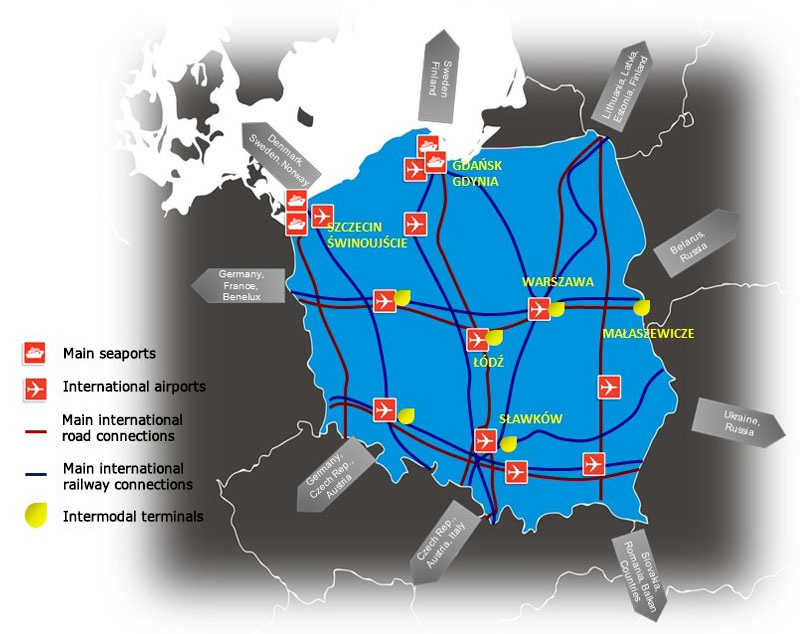

While most, if not all, of the CEECs are supporters of the BRI, some have shown greater participation than others. For instance, Poland, with its well-developed industrial market and logistical importance (it is estimated that 25% of all road transport in Europe is operated by Polish companies) has not only established a strategic partnership with China but is also a founding member of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) – the only CEEC joining the bank so far.

As an important conduit linking Asia and Western Europe in the BRI, in 2013 a high-speed railway started operating from Chengdu, the provincial capital of Sichuan province, in Southwest China, to Łódź, in Poland. The freight train takes only 10-12 days to ship goods from China to Poland, twice as fast as sea transport. Goods arriving in Łódź can then be transported to warehouses or customers in London, Paris, Berlin and Rome via Europe’s rail and road networks.

So far, railway lines for container trains have opened up in 16 Chinese mainland cities, heading to 12 European cities including many CEECs such as Łódź in Poland, Pardubice in the Czech Republic and Košice in Slovakia. Last year, Sino-European freight trains made a total of 815 trips, representing a year-on-year increase of 165%.

To better enhance co-operation between companies from both countries, Poland started offering consular services in Chengdu, while the Łódź government has also set up an office in the city. Such cooperation at sub-national levels has been institutionalised and increasingly offers a best-practice way forward in Sino-CEEC relations.

Meanwhile, Hungary – the first European country to sign a memorandum of understanding (MoU) on BRI co-operation with the Chinese mainland – has also signed deals to build a high-speed rail line between Budapest, its capital, and Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. With the line expected to be completed in 2017, the 85% Chinese-financed project will shorten the travel time between the two capitals from eight hours to three.

As an important country in the Balkan Peninsula, Serbia became China’s first strategic partner among the CEECs, in 2009. This favorable bilateral relationship is very much focused on economic co-operation under the BRI. China’s landmark projects in Serbia include the “Mihailo Pupin” Bridge on the Danube River in Belgrade, the construction of sections of the Corridor 11 highway, and the expansion of coal mines near the “Kostolac” thermal power plant.

The further extension of the Budapest-Belgrade high-speed rail line to Skopje, the capital of Macedonia, and to Athens, the capital of Greece, will give China-bound freight trains another alternative to gain access to the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas. To achieve better synergy, China’s state-owned shipping giant Cosco has recently acquired a majority stake in the Piraeus Port Authority, which complements the 35-year concession to operate Piers II and III at Piraeus port it acquired in 2009.

As the closest port in the Northern Mediterranean to the Suez Canal, Piraeus is not only one of the largest ports in the Mediterranean, but a strategic trans-shipment hub for Asian exports to Europe. China’s exports could reach Germany, for example, seven to 11 days earlier thanks to the abovementioned high-speed rail connection.

Under discussion or pending implementation are Chinese plans to invest on the construction and upgrading of port facilities in the Baltic, Adriatic, and Black Seas, with a focus on production capacity cooperation among ports and industrial and logistic parks along the coastal areas.

Hong Kong’s Unique Role in Sino-CEEC Economic Co-operation under the BRI

A new development model characterised by enhanced connectivity and greater multilateral investment will likely take Sino-CEEC economic co-operation to a higher level. The balancing trend in Sino-CEEC trade, plus the CEECs’ ongoing improvements to industrial capacity and logistical accessibility are highly conducive to the successful implementation of BRI.

Investment opportunities linked to the BRI can include cooperation in logistics along and beyond the Eurasian landbridge which directly connects Asia and Europe. Maritime finance, infrastructure bidding, project management and financing are all highly sought-after by project owners looking for competitive funding/co-operation options and Asian investors looking for more lucrative investment opportunities under Europe’s low interest-rate environment.

With about 60% of Chinese ODI being directed to, or channelled through, Hong Kong, the city, as a regional financial centre in Asia, will continue to be the bridgehead for Chinese mainland enterprises exploring “going out” through investing in greenfield schemes and joint investment projects. These may include smart cities/factories incorporating digital processes that use the Internet of Things (IoT) and Big Data, or conducting mergers and acquisitions (M&As) to reinvigorate companies, or even whole industries. Hong Kong is therefore ideally placed to help enterprises from CEECs look for investment partners from Asia, especially the Chinese mainland.

Possessing definite advantages and extensive experience in helping Chinese mainland enterprises make overseas investments, Hong Kong can play a pivotal role in the expected surge in Sino-European trade and Chinese ODI to CEECs under both the 16+1 format and the BRI, which aims to help companies co-ordinate their global supply chains.

Simultaneously, Hong Kong’s extensive link to other parts of Asia and privileged free-port status, coupled with the presence of cost-effective multimodal logistics options and professional services providers, offer CEECs a wealth of opportunities to make inroads into the burgeoning Asian market. Hong Kong’s position will be further strengthened as the Second Eurasian Land Bridge takes shape and new railway routes start operating.

Viewing Hong Kong as an ideal platform and super-connector to promote their products in mainland China and other markets in Asia, more and more companies from CEECs are using trade fairs and conferences in the city to reach out to Asian buyers and partners. For instance, Poland, as the regional leader in food exports to the Chinese mainland, has run a national pavilion at HKTDC Food Expo since 2013, occupying almost 300 square metres in 2016. This trend is expected to strengthen as companies from CEECs pay more and more attention to Asia due to European markets’ lack of growth drivers such as a sizeable youth population and growing incomes.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Highlights

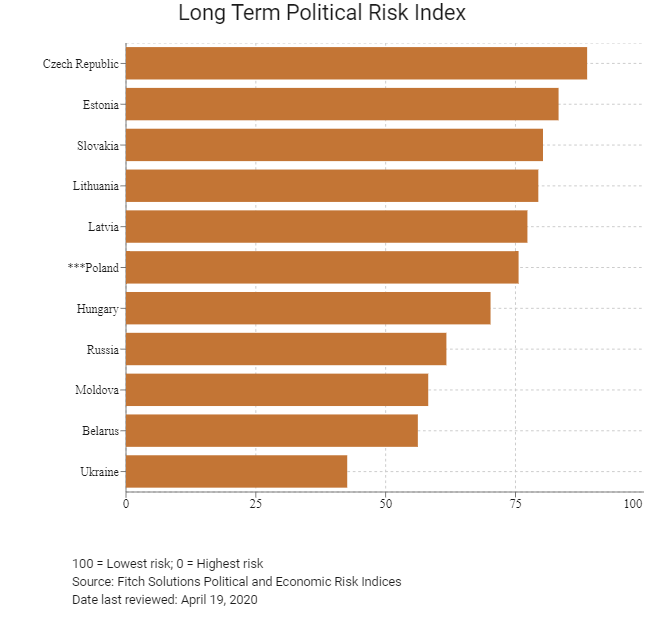

| Political |

|

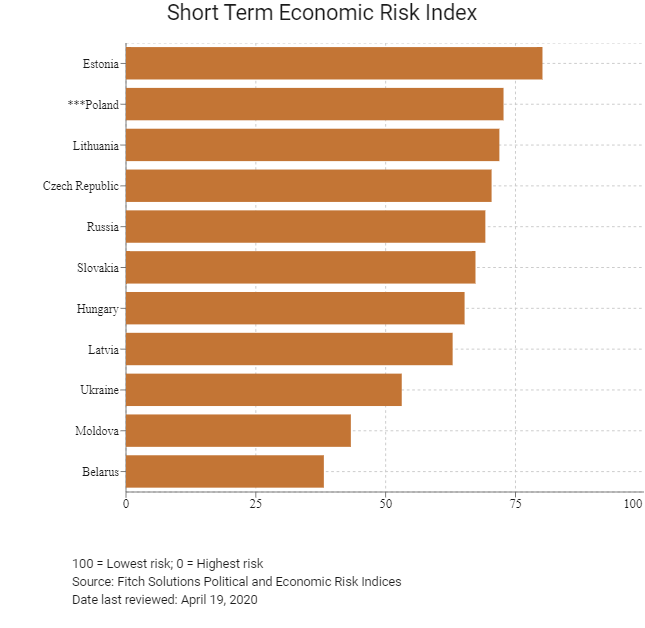

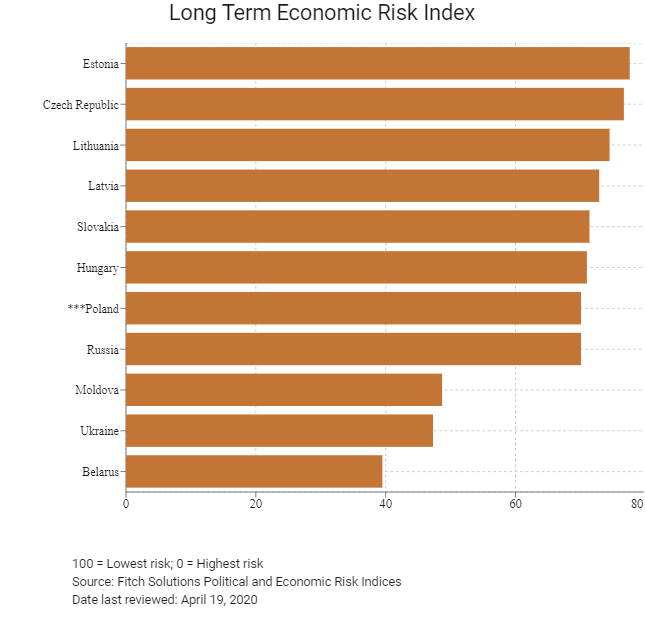

| Economic |

|

Country Overview

Poland is the largest country in Central Europe, in terms of both population and area. The accession to European Union (EU) in 2004 has further integrated its economy with Europe and the rest of the world. Helped by a relatively large domestic market, Poland was the only EU country to have avoided recession during the 2008 global financial crisis. Educated and competent human capital helps attract foreign direct investment (FDI) especially in the automotive, R&D, electronic and chemical sectors. Today Poland has joined the group of countries classified as high-income economies by the World Bank. However, its GDP per capita is at just about two-thirds of the EU average.

|

Key Information

|

|

| Capital | Warsaw |

| Population | 38.5 million |

| Area | 312,685 sq km |

| Currency | Polish zloty |

| Official language | Polish |

| Form of state | Parliamentary republic |

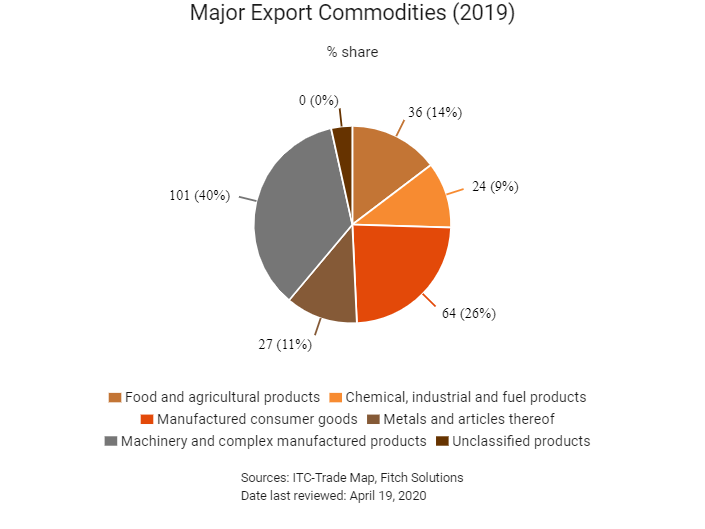

| Major Merchandise Exports (% of total, 2013) | Major Merchandise Imports (% of total, 2013) |

| Machinery & transport equipment (34.0%) | Machinery & transport equipment (30.9%) |

| Manufactured goods (19.2%) | Manufactured goods (16.7%) |

| Food & live animals (9.5%) | Chemicals & chemical products (13.4%) |

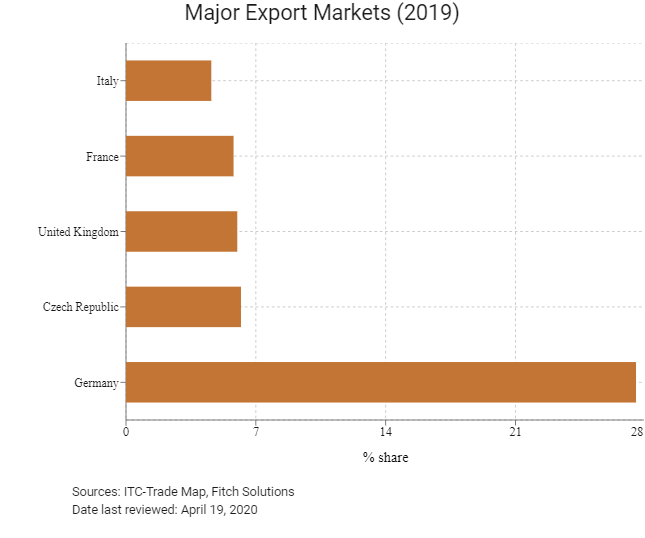

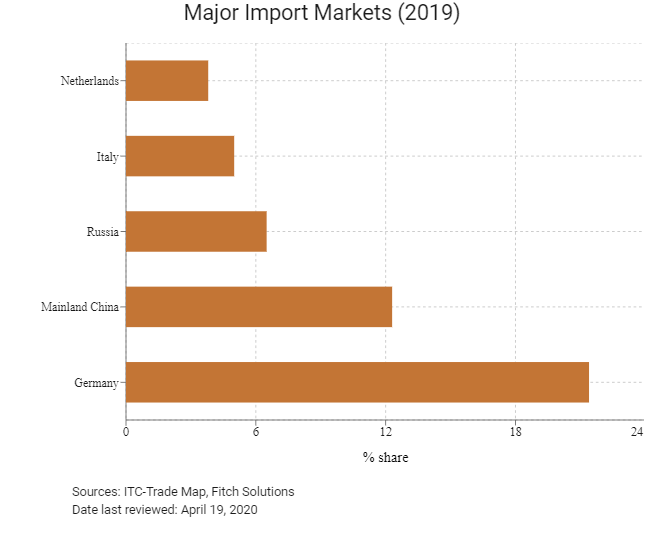

| Top three export countries (% of total, 2013) | Top three import countries (% of total, 2013) |

| Germany (24.9%) | Germany (26.0%) |

| UK (6.5%) | Russia (10.0%) |

| Czech Republic (6.1%) | Netherlands (5.7%) |

Source: Economist Intelligence Unit (www.eiu.com)

Political Trend

Poland is a parliamentary republic. Parliamentary elections are held at least every four years. After being selected as the next president of the European Council, Donald Tusk resigned from his position of Prime Minister in September, and was succeeded by Sejm speaker Ewa Kopacz.

Major challenge for Kopacz is to reconfigure the party and stitch together from various factions that often compete internally. Meanwhile, balancing the goal of public finance reforms and promoting economic growth remained the government’s priority.

In the wake of the Ukraine crisis, Poland has supported increased sanctions against Russia. Currently, Poland relies heavily on Russian natural gas – about 60% of gas demand has been secured by Russian deliveries. Although energy dependence on Russia is unlikely to be reduced in short term, moves to boost its defensive military capabilities have intensified. In early September, NATO agreed on the deployment of a 4,000-strong rapid reaction force to be based in Poland.

Economic Trend

| Economic Indicators | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014* | 2015^ |

| Nominal GDP (USD bn) | 514.9 | 489.9 | 517.7 | 541.6 | 539.0 |

| Real GDP growth (%) | 4.5 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 2.7 | 3.3 |

| GDP per capita (USD) | 13,370* | 12,720* | 13,440* | 14,070 | 14,040 |

| Inflation (%) | 3.9 | 3.7 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 1.2 |

| Budget balance (% of GDP) | -5.0 | -3.9 | -4.0 | -3.6 | -3.0 |

| Current account balance (% of GDP) | -5.3 | -3.6 | -1.4 | -1.2 | -1.9 |

| External debt/GDP (%) | 62.3* | 74.6* | 73.0* | 73.1 | 71.7 |

* Estimates ^ Forecast

Source: Economist Intelligence Unit (www.eiu.com)

In Q2 2014, real GDP grew by 3.3% year-on-year, helped by supportive economic policies and improving conditions in main trading partners. However, the relatively swift pace of expansion observed in the first half of the year appears unlikely to be sustained in the second half. The fragile recovery of the euro area, the dampening effect the Ukraine crisis is having on regional activity, as well as the EU-Russia sanctions are all likely to have negative effect on growth in the second half.

In September, annual inflation rate remained negative for three consecutive months, mostly driven by falling food prices as Russian ban on food imports from the EU has created a domestic surplus in Poland. In an attempt to boost the economy and fight off the threat of persistent deflation, Poland’s central bank cut its benchmark interest rate by 0.5% to a record low of 2% in October.

Following Russia’s annexation of territory in Poland's neighbor Ukraine in March, the country’s political leaders had shown greater appetite on the accession to the euro, seeing it as an additional form of security because it would lock the country firmly into Europe's core. In June, Poland’s president, finance minister and central bank governor agreed that the issue of euro entry should be discussed after the general election next year.

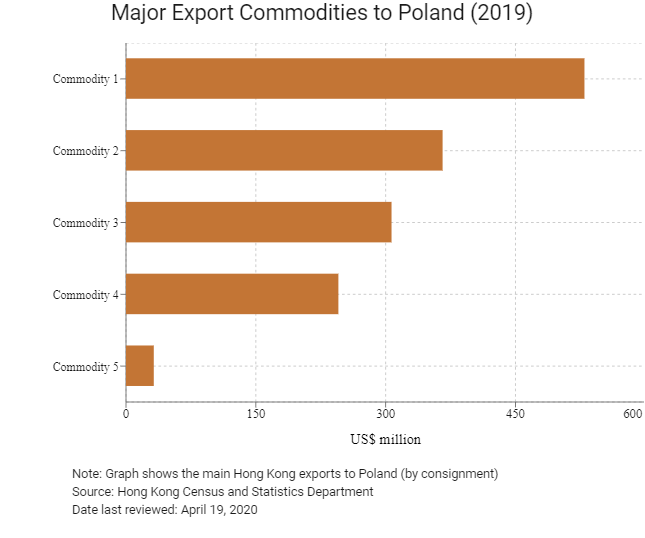

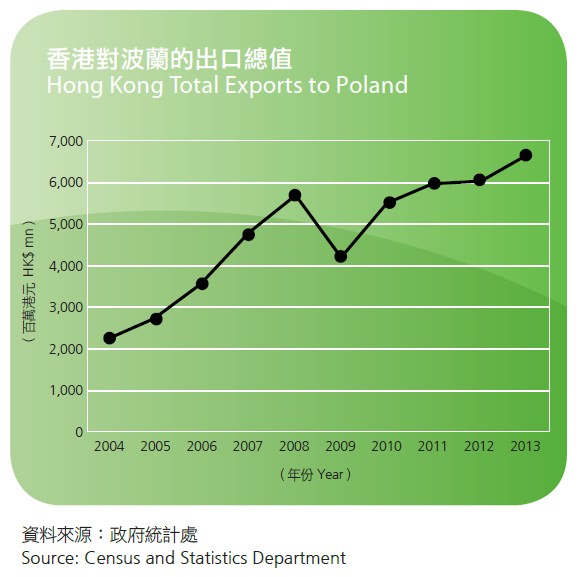

Hong Kong – Polish Trade

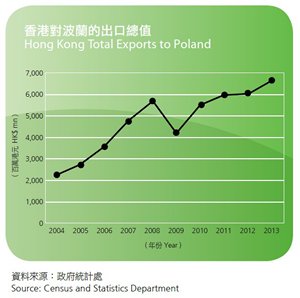

Poland was the 36th largest export market for Hong Kong in 2013, with exports value accounting for 0.2% of Hong Kong’s total exports. Total exports from Hong Kong to Poland increased by 9.8% from HK$ 5,996 million in 2012 to HK$ 6,585 million in 2013. The top three export categories to Poland were: (1) electrical machinery, apparatus & appliances, & parts (+9.7%), (2) telecommunications, audio & video equipment (+41.9%), and (3) office machines & computers (+70.7%), which represented 64.4% of total exports to Poland.

ECIC Underwriting Experience

The ECIC imposes no restriction on covering Polish buyers. Currently, the insured buyers in Poland range from small and medium sized companies to manufacturing arms of foreign companies. For 2013, the number and amount of credit limit applications on Poland reduced by 6.9% and increased by 32.2% respectively, while insured business decreased by 11.2%. Major insured products were electronics (+78.7%), toys (+8.3%) and clothing (+43.0%), which represented 52.9% of ECIC’s insured business in Poland. The Corporation's underwriting experience on Poland has been satisfactory, with only one claim payment made from October 2013 to September 2014, involving clothing.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

East European nation hopes to resume mainland poultry exports and find key role within the Belt and Road Initiative.

Polish poultry producers are hoping to resume exports to China by the end of this month. Poultry imports from Poland to the mainland were banned in December last year following outbreaks of bird flu on farms in the west and south of the country.

Technically, imports cannot resume until three months after the last reported case of the avian influenza strain in the country. Poland has, apparently, been free of infection since 15 March this year.

Discussions as to the resumption of such exports were held in Hong Kong in early May. Leading the talks were representatives of Poland's National Poultry Council (KRD), with a number of leading mainland poultry distributors in attendance.

A recent rise in Poland's poultry production levels has seen the country keen to secure new export destinations, with China regarded as one of the most promising of the international markets. Overall, sales to the mainland are particularly valued, given that certain poultry items – most notably chickens' feet – have a ready market in China, while being virtually unsalable elsewhere.

According to the KRD, should exports resume, the total value of the Poland-China poultry trade could exceed US$560 million a year by 2020. Immediately prior to the ban, Polish poultry exports to the mainland were valued at about $84 million annually.

According to the KRD, Poland is emerging as one of the EU's key poultry-production centres. At present, it produces about 2.5 million tonnes of poultry a year, 40% of which is exported. Approximately 80% of all such exports currently go to other EU member nations.

In other moves, the Polish government has high hopes of playing a significant role in China's Belt and Road Initiative. In particular, it is hoping that the mooted Central Polish Airport (CPA) project could form an integral element of China's plans to enhance its European trading routes.

In addition to air-cargo transport, the CPA initiative would also see the construction of fast rail links, integrated transport corridors, dedicated economic zones and a comprehensive upgraded to the region's energy infrastructure. In light of its potential significance to the overall BRI programme, Poland is believed to be seeking funding from the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank in order to help make the planned CPA a more affordable reality.

At present, Poland, which is pitching itself as China's gateway to Europe, has been keen to nurture its trading relationships with the mainland. In particular, it has been promoting opportunities relating to a number of niche investments, including yachts and designer furniture, while also looking to secure joint opportunities with regard to environmental technologies, medical and mining equipment, cosmetics and the IT sector.

Anna Dowgiallo, Warsaw Consultant

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Since the launch of direct rail freight services linking Łódź (Poland’s third largest city) and Chengdu (the capital of China’s southwest Sichuan Province) in April 2013, Poland has become an increasingly popular destination among traders looking for competitive logistics alternatives to the existing Eurasian ocean lanes and air routes. This popularity has been enhanced by the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian conflict, which has compromised the rail traffic routes passing through Ukraine to such destinations as Hungary and Slovakia.

The initial profits from the increasing level of Asia-Europe rail traffic have been seen as a crucial contributor to the success of Poland’s new national economic roadmap. Dubbed the Morawiecki Plan (after Mateusz Morawiecki, the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Economic Development and Finance), the roadmap shares many common elements with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), envisaging not only an increase in investment, but an improvement in per-capita income and the greater prominence of international trade.

From a Mere Middle-ground Solution to a Market-opening Solution

Following the arrival of the first direct container train from Chengdu to Łódź in December 2012, regular rail freight services linking China and Poland increased significantly. Among these new routes are the Suzhou-Warsaw railway link, which opened in September 2013 and the first to originate from a free trade zone – the Xiamen Haicang Free Trade Port – which has now been operating between Xiamen and Łódź route since August 2015.

This rapid growth has made rail transport, usually considered a middle-ground solution between ocean and air transport, a more attractive logistics option for traders who cannot afford the long shipping time of seaborne freight or the high price of air freight. It has also strengthened Poland’s role as a regional trans-shipment hub in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) for high-value-added, China-bound/Europe-bound products. With most Asia-Europe rail services currently avoiding travelling through the Russian-Ukrainian border, due to the ongoing conflict between those two countries, Poland, as a ready alternative, has enjoyed great success in challenging for the region’s logistics crown.

In order to transport a 40-foot high cube (HC) container from Hong Kong to Poland, cargo owners usually opt for one of the maritime routes, which costs port-to-port around US$1,800 and takes 33 days to reach the port of Gdańsk in northern Poland. In the case of cargo destined not only for the Polish market, traders can also consider other European ports, such as Hamburg in Germany (US$1,800; 32 days), Slovenia’s port of Koper (US$1,700; 25 days) and, more frequently, the Greek port of Piraeus (US$1,600; 22 days) in which China’s Cosco Shipping has lately acquired a majority stake and made the overland connection – road and rail – to major European hubs more practical and convenient.

Source: CEEC-CHINA Secretariat on Logistic Cooperation

Goods arriving from the port of Piraeus, for example, can be distributed across Poland (or to warehouses and distribution centres in other European destinations) via the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T). At the crossroads of the two core TEN-T corridors – the Baltic-Adriatic Corridor (the North-South axis connecting CEE countries with the ports of the Baltic and Adriatic seas) and North Sea-Baltic Corridor (the West-East axis connecting the Baltic States and Poland with Germany and the Benelux countries) – most of the capital cities in Europe are within 2-3 days trucking from Poland. However, the price tag of overland connections between the port of Piraeus and such major CEE cities as Warsaw, Budapest in Hungary, the Slovakian capital Bratislava, Pardubice in the Czech Republic and Belgrade in Serbia can often start at around €1,100.

A direct container train, on the other hand, will take no more than two weeks to arrive in Warsaw, the capital of Poland, thanks to key improvements in route options, performance and customs protocols. For instance, the movement of containers between the broad-gauge (1,520mm) trains used in former Soviet countries, such as Russia, Kazakhstan and Belarus, and the standard-gauge (1,435mm) trains used in China and the EU, can nowadays be carried out within 50 minutes at Khorgas – one of the busiest junctions on the Silk Road Economic Belt near the Chinese-Kazak border.

This speed is one of the major reasons why the rail option has increasingly gained in popularity among traders in dire need of quick (usually same-day) delivery to fulfill their growing e-commerce business requirements, although the cost can easily rise to a level more than double that of ocean freight – the cost of sending a 40-foot HC container by rail from Shenzhen to Warsaw, for instance, is about US$4,000 station-to-station.

At first sight, such a middle-ground alternative is not very tempting for traders who want to ship Hong Kong-origin products to Europe, due to the extra cost and time needed for trucking the products by bonded trucks to mainland train stations. It is, however, becoming more routinely undertaken by Hong Kong manufacturers who produce and export to Europe direct from factories across the border.

Given the higher price tag and limited capacity (around 60-65 containers per train) compared to ocean transport (11,000-plus containers per vessel), rail is not suitable for all products. According to Hatrans Logistics, the Łódź-based logistics company that operated the first direct rail freight train between China and Poland, the items being transported by Europe-bound trains are mainly electronics, auto parts, electrical appliances and medical devices, while advanced machinery and equipment, automobiles and building materials are most typical of the products being sent on China-bound trains. More intriguingly, food and beverages (F&Bs) have become a frequent cargo on such Eurasian trains.

To better utilise the idle loading capacity on trains returning to China, Polish exporters have started to work with logistics players to develop new possibilities, while some visionary Chinese companies have even set up their own sourcing teams to seek out attractive European products to fill containers on their return journey.

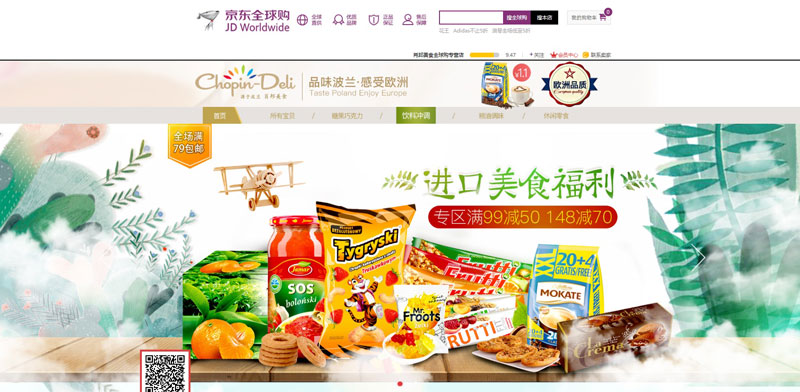

Source: www.chopin-deli.com

Hatrans Logistics, for example, has launched Chopin-Deli, a web shop, on JD Worldwide, China’s cross-border e-commerce platform, in order to promote a number of F&B items, such as coffee, tea, juices, spirits, jam and confectionery. It also runs a showroom in Chengdu showcasing other niche products, including cleaning materials for damaged soil, building materials (wooden flooring panels), lifestyle products (health/diet supplements and sport drinks) and personal care products (cosmetics and hair care) that are seen as having considerable potential in the mainland market.

According to the Association of Polish Butchers and Meat Producers, Chinese and Asian restaurants are present in almost every Polish town, with 95% of the ingredients used in food preparation actually locally grown. This highlights not only how capable the Polish food industry is when it comes to meeting the needs of Chinese and Asian chefs, but also demonstrates the huge potential for Polish fresh produce and processed F&Bs in the Chinese and Asian market. To further bolster customer confidence, Poland has positioned itself as the only EU country to put in place three national food quality schemes – the QMP (Quality Meat Program), the PQS (Pork Quality System) and the multi-product QAFP system (Quality Assurance for Food Products) – in order to guarantee both the safety and quality of its meat products.

Although the outbreaks of H5N8 avian influenza in the Ostrowski and Moniecki Districts of Poland have caused a suspension of the imports of Polish poultry meat and associated products (including eggs), the fact that Hong Kong imported about 20,500 tonnes of frozen poultry meat and 4.8 million poultry eggs from Poland in 2016 shows how well-received Polish food products are by consumers in Hong Kong. This, in turn, opens wide a new window for Polish-Hong Kong co-operation – the pairing of Polish F&Bs with the complementary Asian culinary skills and flavours for the enjoyment of Asian foodies.

Meat products aside, Poland – an EU leader in the export of apples, berries, mushroom, cucumber, onion and garlic – has been more active in promoting its fruit and vegetables to the Asian market. Following President Xi Jinping’s visit to Poland in June last year and the co-operation agreements signed between the two governments, Polish apples were given the green light to enter the Chinese mainland market in September. As Asian manufacturers have become more knowledgeable about the quality and value for money of Polish crops, Polish apples, apple juices, cereals and frozen vegetables have become more widely available as part of the global food supply chain.

Following the success of Polish apples, it’s hoped that other Polish fruit such as strawberries, raspberries, currants and blueberries (Poland is the biggest producer of blueberries in Europe) may also do well in the Chinese market, especially given the complementary nature of the Polish harvesting season to those in other fruit-producing regions, notably Latin America and New Zealand. Polish berries are already selling in Hong Kong, which is widely considered by Polish fruit growers to be a good test bed for the other Asian markets, especially the Chinese mainland.

Many Polish F&B companies see Hong Kong as a trendsetter for wider Asian food consumption. The case of LEI Food & Drinks, a Polish manufacturer and exporter of premium F&B products, is a good example of how Polish F&Bs are entering the Asian market through a direct Hong Kong presence. From its warehouses in Hong Kong, LEI is supplying a number of the city’s high-end hotels with high-quality apples and fresh juices, produced using the traditional method of cold pressing with no preservatives or sugar added, while the company is also introducing the Asian market to its organic apple chips and sausages, isotonic drinks and alcohol beverages through a number of different Hong Kong channels, such as trade fairs and events.

As revealed by the National Association of Fruit and Vegetables Producer Groups, Polish soil, with little history of artificial fertiliser use, is so green and clean that it can be easily converted to organic farming use in just two to three years, compared with the six to seven years required in other EU countries. Thanks to EU financial support since the country’s accession to the union in 2004, Poland has developed state-of-the-art infrastructure with regard to agriculture, crop storage and food processing.

As the second biggest poultry producer in the EU – behind only France – Poland, has been sharing its best practices with other European farmers with regard to hen house automation and management. In addition to natural, nutritious and safe foodstuffs, the commercialisation of agricultural experience and technology is another promising field for Hong Kong-Polish partnerships, by dint of the city’s established technology marketplace and proven record of international collaboration in the fields of test-bed set-up, proof of concept (PoC) trials and solution customisation.

More Vibrant Trade Calls for More Vibrant Investment

With Sino-EU trade expected to top the US$1 trillion mark by 2020 (rising from around US$570 billion in 2016 – largely on account of the growing demand from mainland consumers and manufacturers for better, safer and tastier European products and for supplies of raw materials and parts and components from their European counterparts –rail transport is poised to play an even more important role in the Eurasian supply chain. This warrants improvements in infrastructure and more investment from both domestic Polish sources and overseas private investors and institutions, including the EU.

The early profits from the increasing level of Asia-Europe rail traffic have been considered by the Polish government as a crucial contributor to the success of the Morawiecki Plan, which foresees an investment of more than PLN2tn (US$490bn) through to 2020. The Morawiecki Plan shares many things in common with the China-proposed BRI, envisaging not only more robust investment in and out of Poland, but an improvement in per-capita income and greater role for international trade.

According to the targets set under the terms of the Morawiecki Plan, Poland is expecting its per-capita GDP to rise from 69% of the EU average to 79% by 2020, which, if achieved, will mean fresh demand for higher-quality, greater-variety imports. The plan also aims to boost the level of investment from its current level of 20% of GDP to 25% by 2020, as well as anticipating a 70% increase in outward foreign direct investment (FDI), giving rise to growing opportunities for services providers worldwide to facilitate not just foreign investment in Poland, but outbound investment by Polish institutions and enterprises.

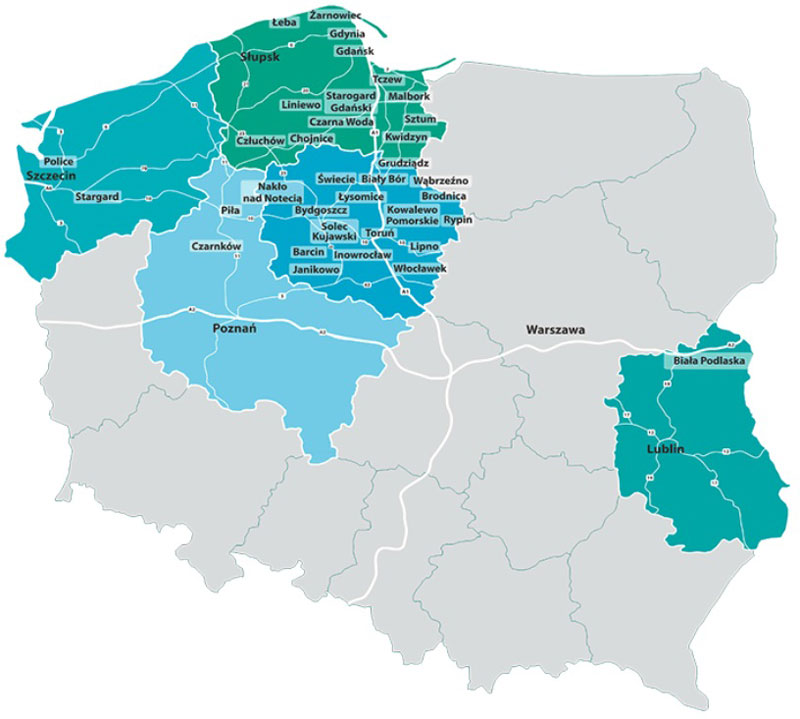

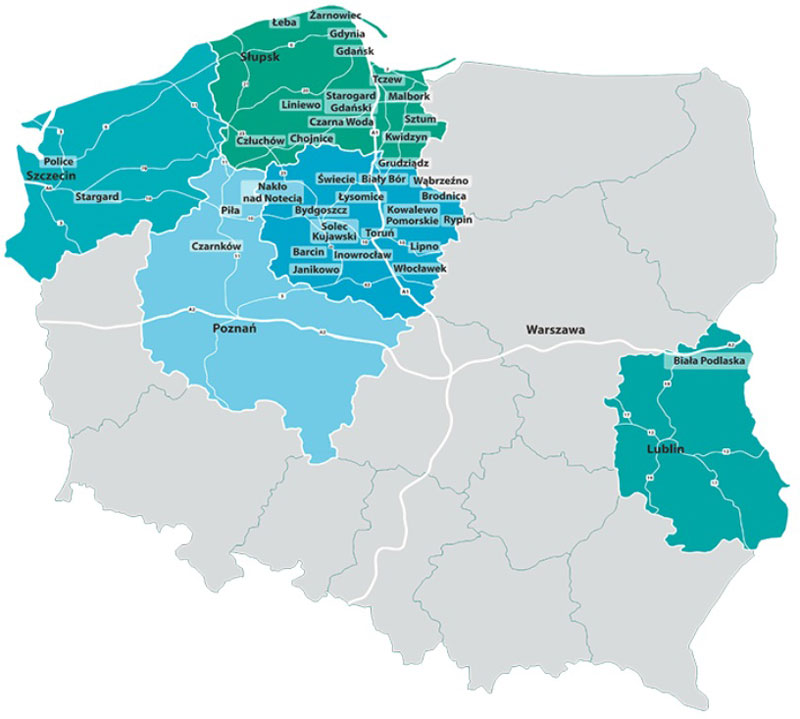

At the regional level, local governments have been very active in devising new projects and competitive incentives to attract both domestic and foreign investors to build and/or upgrade existing infrastructure so as to better tap the increasing demand for loading/unloading services and manufacturing/processing facilities expected with the growing proliferation of Eurasian rail operations. The recent enlargement of the Pomeranian Special Economic Zone (PSEZ) in the Lublin region (or Lubelskie voivodeship in Poland) at the Biała Podlaska county near the Polish-Belarusian border, is a case in point.

Source: Polish Investment and Trade Agency (PAIH)

As one of the 14 SEZs in Poland, PSEZ has been active in implementing a range of supplementary ventures and expansion activities, including the Gdańsk Science and Technology Park, which supports the development of start-ups, ICT and new technologies, and the Baltic Port of New Technologies in Gdynia, which has focused on the construction of a modern environment supporting the shipbuilding and related industries.

Under the Regulation of the Council of Ministers of 30.12.2016, the reach of PSEZ, thanks to its proven track record, has been further extended to eastern Poland. In the Biała Podlaska county of the Lublin region, the PSEZ is planning to build a logistics centre or trans-shipment hub by utilising the infrastructure of a defunct military airport and the existing inland trans-shipment facility with an aim of integrating with the New Silk Road Route connecting China and West Europe.

According to Pomeranian Special Economic Zone Ltd, the management company behind the PSEZ, the enhanced rail connection has made it more viable for manufacturers to relocate their production (or at least some of the manufacturing processes of their products destined for the European market) to Poland or the CEE region in general. The new Biała Podlaska Subzone, which is located close to the Polish-Belarusian border, is seen as serving as not only a logistics hub for trans-shipment from rolling broad-gauge onto a fleet of standard-gauge (1,435 mm) carriages or deconsolidation before sorting and sending directly to customers or warehouses in Europe, but also as a means of enabling manufacturing relocation across the country or even the whole CEE region.

Putting the new subzone under the management of PSEZ is seen as the best way of guaranteeing synergy across the country’s multimodal transport capacity. This will enable better connections with the inland cargo port in Biała Podlaska with the tide and ice-free seaports at Gdańsk/Gdynia in the Pomerania region and Szczecin/Świnoujście in the West Pomerania region, so as to best increase the overall freight turnover. The logistics advantages aside, companies that invest in the new subzone can also count on a higher level of tax relief – from 50% (for large companies with 250+ employees) to 60% (for medium-sized companies) and 70% (for micro and small companies), based on the cost of their investment or the two-year cost of their newly-hired employees.

Another bustling Polish region actively enticing Chinese investment is Łódź in Central Poland. Chinese investors operating a plastics manufacturing plant producing parts for TVs, computer panels and other entertainment equipment and an upcoming glass factory have already begun to reap the benefits of the region’s strategic location, which allows for rapid delivery not only between China and Poland, but across the whole European continent.

In order to attract Chinese investors, the local government and the Łódź Special Economic Zone have prepared far reaching plans for the development of new infrastructure and industrial zones near the main cargo terminals to facilitate co-operation between Chinese enterprises and the region’s strong local business community, especially in the fields of electrical engineering, food processing, alcoholic beverages, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals.

Going from Strength to Strength following Successful Investment Footprints

Hong Kong, with its FDI stock of US$418.7 million as of the end of 2015, is ranked 24th on the list of Poland’s inbound foreign investors. Among Asian investors, however, the city trailed only South Korea and Japan. A number of the city’s most well-known companies, including Hutchison Ports (formerly known as Hutchison Port Holdings (HPH)), Orient Overseas Container Line (OOCL), Kerry Logistics and Cathay Pacific are the examples of successful Hong Kong investment in Poland.

Since 2005, Hutchison Ports, a subsidiary of CK Hutchison Holdings, has carried out a number of investment programs at the port of Gdynia, transforming the Gdynia Container Terminal (GCT) into a modern container handling facility and strengthening the Port’s role as a feeder port connecting Poland with other European hubs in Germany (Bremerhaven and Hamburg) and the Netherlands (Rotterdam). In 2015, GCT completed its deep-water port development program, including the addition of a deep-water berth for vessels of up to 19,000 TEUs and an expansion of its rail terminal.

Hong Kong-based container carrier OOCL, a member of the former G6 Alliance, has recently added a direct port call to Gdańsk in its Asia-Europe (AET) service loop. Fuelling optimism for the floundering Asia-Europe trade lane, the direct port call makes it more convenient for Chinese and Asian companies to ship parts and components directly to Gdańsk for processing in close vicinity to the seaport, at places such as the Pomeranian Logistics Centre, in order to enjoy both lower operational cost and the tariff-free status of being Made in the EU.

Ensuring customers have smooth access into and out of CEE, Hong Kong-based Kerry Logistics inaugurated a shared service center (SSC) in Poznań in western Poland in November 2016 and a new office in Warsaw in March 2017 as part of its efforts to increase its European coverage in line with its customers’ developments in the region. While the new SSC is aimed at improving the overall cost efficiency and service competitiveness in the region, the new Warsaw office will support customers with regard to international freight forwarding via ocean, air and road freight services, as well as in customs brokerage.

Hong Kong’s flagship carrier, Cathay Pacific Airways (CX), with no direct flight connection with Polish airports, remains in the “uncharted brand territory” for Polish passengers. It did, however, choose Kraków, the second largest city in Poland, as the site of its fourth Global Contact Centre in April 2016. The capital of southern Poland’s Małopolska region, for the last three years Kraków has been ranked number one in Europe for outsourcing services [1]. Among the first Asian companies to have a direct business presence in the city, CX’s new Kraków centre handles inbound calls from Africa, Europe and the Middle East seeking with regard to bookings, baggage, online check-in, website technical issues and more and boasts a team of 120-plus young, multilingual professionals.

The unique combination of its diversified investment footprint and its ready professional and financial advisory services cluster, complete with extensive global networks and affiliations, has made Hong Kong a ready partner for Polish enterprises, intermediaries and project owners hoping to grow alongside Chinese investors under the framework of either China’s BRI or Poland’s own economic roadmap.

As these development strategies and frameworks progress and become more specific and concrete, more ambitious proposals involving increasingly technical and complex projects are expected to roll out. In turn, these will require more intricate and sophisticated project finance facilities and more comprehensive professional services of the sort that Hong Kong excels in providing, given its status as a super-connector for international collaboration.

With some 60 members from financial agencies, banks, investors, law firms to insurance companies, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority’s Infrastructure Financing Facilitation Office, for example, is seen as an important enabler for the ongoing development of Hong Kong as an infrastructure financing hub. In particular, its role is to help companies that are eager to invest in infrastructure projects survive the ever-changing challenges of infrastructure investment funding and financing.

Any future expansion in trade and investment will lead to a rise in demand for a number of legal services, including those relating to contractual arrangements, project management and dispute resolution. In this regard, any involvement by Hong Kong service providers offer considerable reassurance to local, Asian and Polish traders and investors as they look to benefit from the Belt and Road, on the back of the city’s trusted common law system and independent judiciary.

[1] Tholons Outsourcing Destinations List

Editor's picks

Trending articles

The Visegrad Four (V4) nations, consisting of the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia, have had remarkable success in aligning and strengthening their economies to compete and play a dominant role in the regional economy of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). They are poised to benefit most from the multifaceted alignment of the “16+1” format co-operation between Central and Eastern European countries and China) and Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The V4 countries, located in the heart of Europe, have seen rising trade and investment flows on the back of strengthened Sino-CEE co-operation and connectivity. Meanwhile, more and more V4 businesses have taken on a more global perspective in searching for new markets.

Hong Kong, given its unique combination of a vibrant capital market and a large professional services cluster with extensive global networks and affiliations, can be a crucial link in providing the important capital flows and the highly sought-after assurance to new-to-the-market V4 enterprises and investors.

Enhanced connectivity and increasingly vibrant investment flows have not only made it possible for each of the V4 countries to reinvent and reposition itself in the bigger picture of Sino-CEE co-operation, they have also provided traders and manufacturers with more possibilities in terms of regional distribution and supply chain management.

V4 Countries as Core BRI Partners in CEE

Central and Eastern European Countries (CEECs) have played an increasingly pivotal role in China’s foreign policy, and are key partners in the BRI. The “16+1” format and the BRI have multifaceted alignment as both development initiatives led by China are aiming at intensifying and expanding co-operation with the 16 CEECs, including investment in infrastructure and cooperation in industry and technology development.

Different CEECs may benefit differently from the strengthening Sino-CEEC co-operation and connectivity subject to their own development plans and national strategies. The V4, which play a leading role in the regional economy and have had remarkable success aligning and strengthening their economies to compete effectively regionally and internationally, are poised to benefit most in drawing trade and investment interest.

Representing more than half of the population and nearly two-thirds of the economic output of the 16 CEE member countries under the umbrella of the “16+1” format, the V4 are naturally important and active participants in the BRI. They offer a progressively interesting logistic alternative for shippers and their forwarders moving cargo between Asia and Western Europe, which is considered a priority to the success of the BRI as it aims to enhance the connectivity between Asia, Europe and Africa.

Banking on the good Sino-V4 relations and China’s continuous implementation of its “going out” strategy, China’s outbound direct investment (ODI) in the V4 countries has been flourishing, while bilateral trade blossoms. In the five years ending 2015, China’s ODI to the V4 grew by more than 65% from US$769mn to US$1.28bn, accounting for nearly two-thirds of China’s ODI in the 16 CEECs. Though China’s investment in V4 countries and the other CEECs is far from significant in the light of China’ total ODI, Hong Kong’s professional services providers and Chinese-funded corporate structures have quite often been involved in Sino-V4 investment deals such as M&As and takeovers.

While cash-rich Chinese investors have already made successful inroads into V4 countries by acquiring promising businesses over the past decade, more brownfield and greenfield projects, both private and public, are expected to materialise in the bloc in the coming years. Such a sustained wave of Chinese investment, plus generous funding from European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) supporting mega infrastructure projects, research and innovation and small businesses (including start-ups), will certainly give a big shot in the arm for the V4 economy to rejuvenate its industrial and commercial prowess.

Amount budgeted for period 2014-2020 Czech Republic Czech Republic, through 11 national and regional programmes, benefits from ESIF funding of €24 billion representing an average of €2,281 per person over the period 2014-2020 Hungary Hungary, through 9 national and regional programmes, benefits from ESIF funding of €25 billion representing an average of €2,532 per person over the period 2014-2020 Poland Poland, through 24 national and regional programmes, benefits from ESIF funding of €86 billion representing an average of €2,265 per person over the period 2014-2020 Slovakia Slovakia, through 9 national programmes, benefits from ESIF funding of €15.3 billion representing an average of €2,833 per person over the period 2014-2020

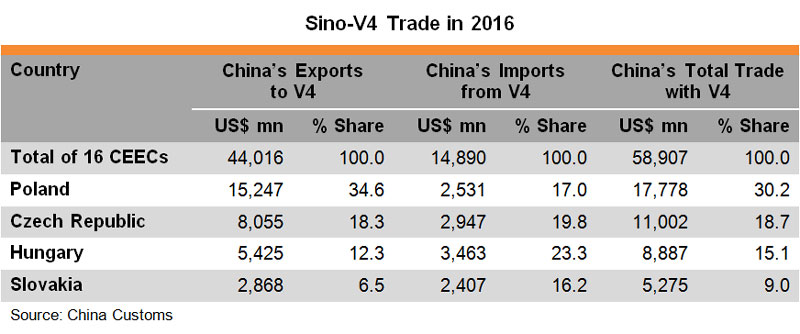

Source: European Commission |

Just as they are the leading recipients of Chinese ODI in CEE, the V4 countries are also the leading trading partners of China among the 16 CEECs, accounting for 73% of the total Sino-CEEC trade in 2016. Trade between China and CEECs has remained unbalanced, however. This unbalanced trade pattern – China exported nearly twice as much as it imported from the V4 countries in 2016 – has become a raison d’etre for deeper and wider Sino-V4 cooperation from mergers and acquisitions (M&As) and takeovers to higher value-added manufacturing, technology exchanges and infrastructure and real estate (IRES) projects.

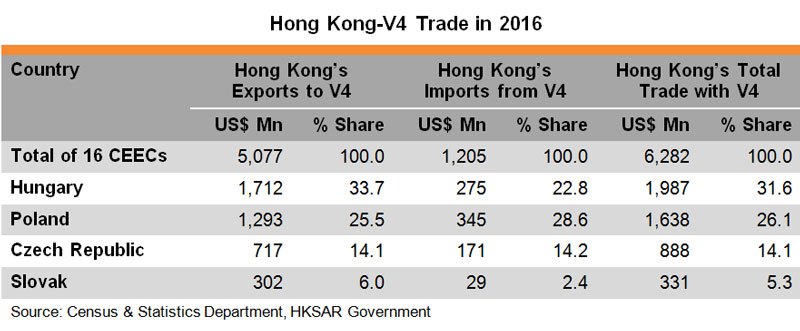

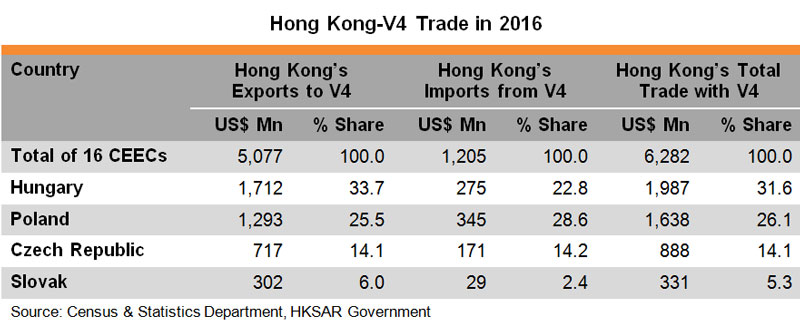

The pattern of Hong Kong’s trade with V4 countries coincides with that of Sino-V4 trade – with the four countries accounting for more than 75% of Hong Kong’s total trade with the 16 CEECs in 2016. Boasting a year-on-year growth in trade of between 9% and 22%, (compared to the regional average of less than 7%) Hungary, Poland and Slovakia were not only Hong Kong’s key trading partners in the CEE, but the city’s fast-growing export destinations in the region last year.

As the vibrant Sino-V4 investment flows are playing an increasingly important and active role in nurturing V4 businesses to take on a more global perspective, more and more V4 enterprises are looking further afield in their search for new markets. This is also partly due to the dire need to compensate for the loss of the Russian market due to the ongoing economic sanctions between the EU and Russia. In this regard, Hong Kong, widely considered a safe and clear-cut gateway for V4 companies to explore the Chinese mainland market, is seeing an encouraging inflow and expansion of well-known V4 enterprises, products and brands.

The unique combination of a vibrant capital market with diverse financing channels and a large professional and financial advisory services cluster with extensive global networks and affiliations has thus made Hong Kong an irreplaceable partner for V4 investors, intermediaries and project owners hoping to take advantage of BRI and “16+1” opportunities. As a regional hub for legal services and dispute resolution underpinned by a trusted common law system and an independent judiciary, Hong Kong can be a crucial link in providing highly sought-after assurances to new-to-the-market V4 enterprises and investors.

New Positions of V4 Nations in Sino-CEE Co-operation

Strengthening Sino-V4 trade and investment flows are certainly good signs of the successful implementation of the 16+1 format and BRI in CEE. They have empowered the V4 countries to reinvent and reposition themselves in the bigger picture of Sino-CEE co-operation, while providing traders and manufacturers with far more possibilities in terms of regional distribution and supply chain management.

Poland: Profiting from Increasing Asia-Europe Rail Traffic

Poland, as the region’s largest economy, has successfully captured the lion’s share of the increasing Eurasian rail traffic and developed itself into a rail logistics hub for Asia-Europe cargo trains, thanks partly to the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian conflicts that have compromised the Eurasian rail traffic passing through Russia and Ukraine to Hungary or Slovakia. This, together with the nation’s unrivalled advantage of being the only one among the V4 countries to have access to open sea, has made Poland a natural choice with respect to regional distribution in CEE.

New projects, such as the Pomeranian Special Economic Zone (PSEZ) in Biala Podlaska near the Polish-Belarusian border, will also further empower the country to better accommodate the increasing demand for railway track gauge change (due to the differences of the Russian broad-gauge system and the European standard gauge system), transshipment and even manufacturing processing facilities.

Riding on the better Asia-Europe rail connection, and the cheaper rail freight due to Asia-bound trains not usually being as fully loaded as Europe-bound trains, Polish companies such as vegetables and fruit growers have started to send apples and other processed food to the Chinese market by rail. This trend has also led to Hong Kong traders and service providers becoming a lifestyle showcase for Polish food and beverages including wine, beer, spirits, fruit and derivatives such as jam, juices and cosmetics.

Hungary: Leading the Way in BRI Co-operation

Hungary is the first European country to sign a memorandum of understanding (MoU) on BRI cooperation with the Chinese mainland. The country’s “Opening to the East” policy is very much in line with the BRI and has been well received by investors such as China’s leading electric automaker BYD, which opened its first fully-owned bus plant in Europe in the northern Hungarian town of Komarom in April this year. Meanwhile, several well-known Hungarian companies, including the world-leading Building Information Modeling (BIM) software developer and a significant player in the field of global female healthcare, have continued to grow their Asian businesses through either their regional headquarters or partners in Hong Kong.

Being the No.1 destination of Chinese outbound FDI in CEE, Hungary is also an important partner to RMB internationalisation in Europe. Home to the regional headquarters of the Bank of China (BOC), which has operated a subsidiary in the country since 2003 and maintained a full-fledged branch since 2014, Hungary was selected by the Bank to launch its first RMB clearing centre in CEE in October 2015 and its first Chinese RMB and Hungarian forint debit card in Europe in January 2017.

As regards logistics, the thrice-weekly direct cargo flights from Hong Kong to Budapest, the capital of Hungary, have made the country a possible air hub for cargo distribution in CEE, while the ongoing project of the high-speed Budapest-Belgrade rail line (which is expected to achieve substantial progress this year) and its further extension to Skopje, the capital of Macedonia, and the Greek capital Athens, will afford the landlocked country a better connection with seaports in the Adriatic and Mediterranean Seas. There is also the already serviceable China-Europe land-sea fast intermodal transport route connecting Hungary with the Greek Port of Piraeus operated by China COSCO Shipping.

The Czech Republic: Boom Time for China-Led M&As

Having one of, if not the best flight passenger connections with the Chinese mainland among CEECs, the Czech Republic welcomes more Chinese tourists (more than 300,000 in 2016) than any other country in the region. The increased belly cargo capacities plus the new cargo flights routing from Hong Kong to Prague have also enabled Chinese express delivery companies to better fulfill the cross-border e-commerce bonanza.

Boosting one of the densest rail networks in Europe (after Luxembourg and Belgium), the Czech Republic has also attracted many multinationals such as Foxconn and Amazon to set up regional logistics centres. As a leading global producer of wheelsets, wheels, axles and other wheelset components for rolling stock, Czech companies are also heavily involved in the expanding Eurasian rail development. One such company, which won the MTRC contract to supply wheels for MTR passenger trains in 2015, opened its first Asia office in Hong Kong in September 2016.

Aside from tourism and logistics, Czech Republic sees a wide array of Chinese-led M&A deals spanning sport, real estate, airlines, travel agencies, hotels, breweries and most recently a DIY and gardening chain. Ongoing deals, including the takeover of the Group Skoda Transportation, the biggest producer of railway vehicles in CEE, by China Railway Rolling Stock Corporation (CRRC), are expected to open the door for Chinese manufacturers to march into the European market, source of technology and pool of talents. Some of the M&A deals have been done through the corporate structures of Chinese enterprises in Hong Kong, while at least one famous Czech glass and lighting company has set up a holding company in Hong Kong to stay close to both the production base in the Chinese mainland and the rosy residential and commercial property market in Asia.

Slovakia: BRI Investment and the Route to Modernisation

Slovakia, with the highest per-capita car production in the world, has been a magnet for auto-related investment in CEECs. All three established car producers – Volkswagen, Peugeot Citroën and Kia – and their tier 1 and tier 2 suppliers are constantly expanding their manufacturing plants in the country, while the investment project Jaguar Land Rover (starting production in 2018) has become the largest business case in Europe during the last seven years.

The recent acquisition of the country’s largest steel mill in Košice by He-Steel Group of China, the world’s second largest steel maker, has not only helped the Chinese steel maker to gain a foothold in the European steelmaking industry to avoid prohibitive EU anti-dumping duties on steel imports, but also highlighted Slovakia’s strategic location to facilitate manufacturing industries such as automotive and electronics that utilise raw materials coming from non-EU European suppliers such as Ukraine.

To prepare for the expected increase in rail cargo traffic between Europe and Asia and strengthen its attractiveness for international manufacturing and logistics companies, Slovakia, riding on its favourable catchment zone in between seaports in southern Europe (e.g., the Slovenian Port of Koper and the Italian Port of Trieste) and northern Europe (e.g., the Port of Hamburg), is active in developing and upgrading its infrastructure. This includes the modern transshipment facilities of Slovakian cities such as Bratislava, the country’s capital, and Košice in eastern Slovakia, close to Ukraine, Hungary and Poland.

Hardware aside, the Slovakian government is keen on adopting and promoting the use of new technology such as electronic locks and electronic customs clearance systems to allow cargo owners and forwarders to facilitate a more effective means to track or trace cross-border cargo movement. Meanwhile, the country is stretching its wings wide to Asia, including, but not confined to, a plan to start a double tax treaty negotiation with Hong Kong soon.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

GDP (US$ Billion)

585.82 (2018)

World Ranking 22/193

GDP Per Capita (US$)

15,426 (2018)

World Ranking 59/192

Economic Structure

(in terms of GDP composition, 2019)

External Trade (% of GDP)

106.2 (2019)

Currency (Period Average)

Polish Zloty

3.84per US$ (2019)

Political System

Unitary multiparty republic

Sources: CIA World Factbook, Encyclopædia Britannica, IMF, Pew Research Center, United Nations, World Bank

Overview

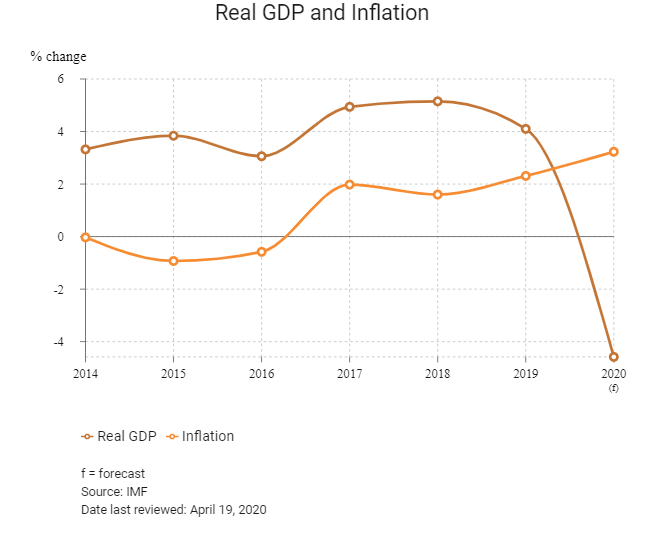

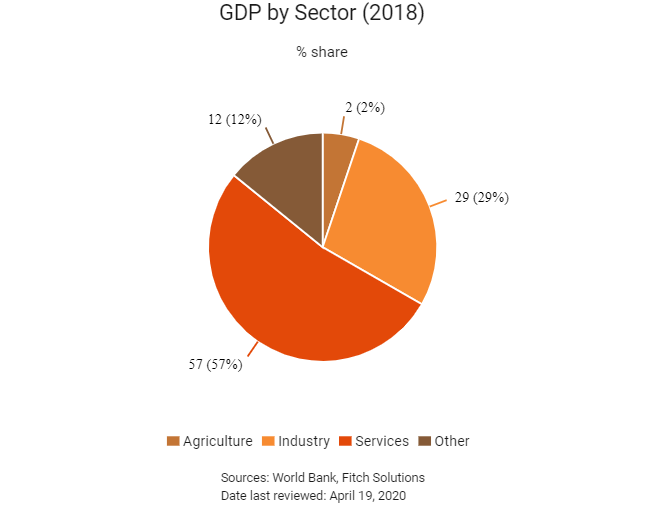

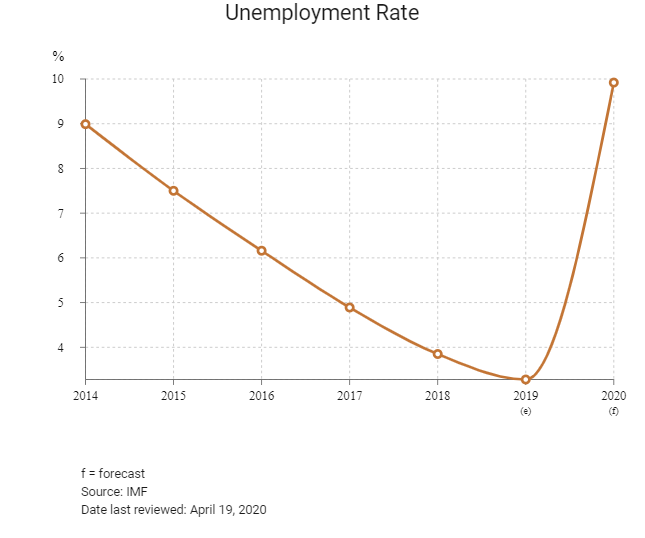

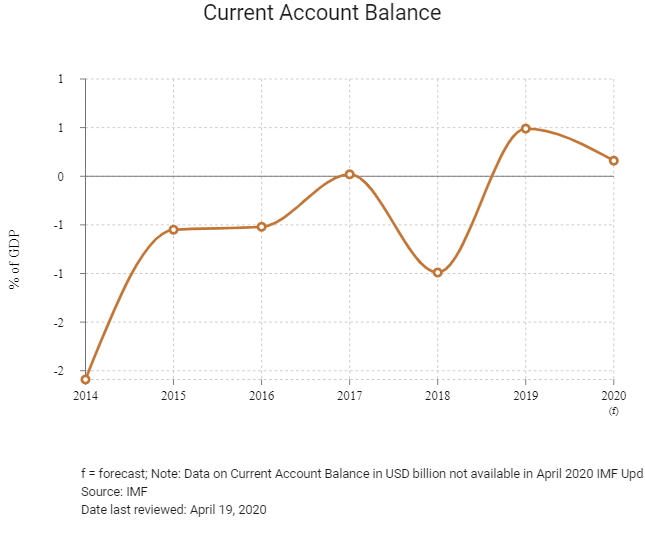

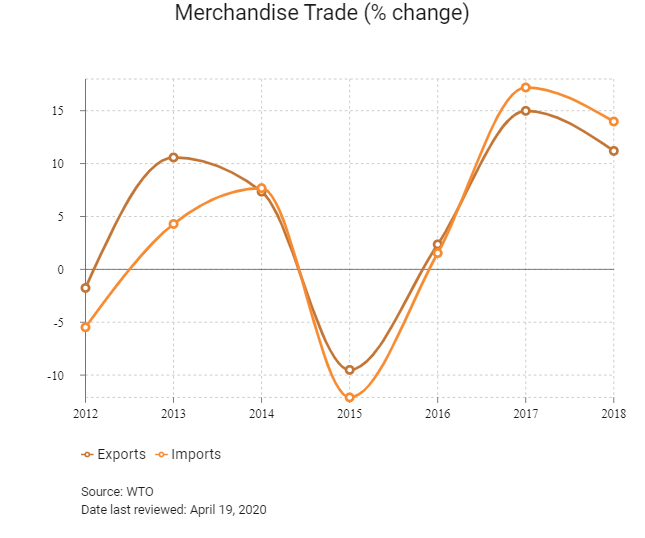

Poland has reached high-income status over a relatively short period of time, and this has translated into remarkable progress in poverty reduction and shared prosperity. Few middle-income countries have experienced such consistent broad-based growth at both a fast and stable rate. Owing to a very well developed financial sector, services contribute maximum share to the country’s GDP. The Polish economy continues to perform strongly, with real GDP growth reaching 5.1% in 2018. The three main challenges ahead for Poland are a shortage of labour in the economy, pro-cyclical government policies encouraged by the political calendar and adverse global factors.

Sources: World Bank, Fitch Solutions

Economic/Political Events and Upcoming Elections

December 2017

The resignation of Prime Minister Beata Szydło and subsequent promotion of Mateusz Morawiecki, the former deputy prime minister and minister of economic development and finance, marked significant changes within the governing Law and Justice party (PiS) leadership. Morawiecki took over as prime minister of the PiS government.

July 2018

General Electric (GE) signed a contract with Elektrownia Ostrołęka to build a 1GW ultra-supercritical coal power plant in north east Poland. Under the contract, GE would design and construct the power plant and manufacture and deliver boiler and steam turbine generators. GE would also supply air quality control systems in accordance with the latest European Union (EU) standards in terms of local emissions. The power plant, called Ostrołęka C, was likely to generate sufficient power for 300,000 Polish homes. The plant was expected to start operating in 2023, according to a GE press release.

October 2018

Poland's ruling PiS party increased its hold on regional parliaments following local elections.

May 2019

The European Investment Bank had signed a financing agreement with Bank Gospodarstwa Krajowego (BGK), provided a EUR300 million (USD335.5 million) loan for a highway upgrade project in Poland.

August 2019

Telecom gear-maker Ericsson would increase production and invest further in its Tczew plant in Poland in preparation for the ramp up of a next-generation 5G mobile network across Europe.

October 2019

The ruling PiS secured victory in the country’s parliamentary election, won nearly 44% of votes and increased its share of seats in the lower house. The biggest opposition bloc, Civic Coalition (KO), secured 27.2% of votes and the Left Alliance secured 12.5%.

January 2020

Poland’s new Finance Minister Tadeusz Koscinski announced that he wanted to tax United States tech company AirBnB on the revenues it earns in Poland.

February 2020

BGK signed an agreement with the European Investment Fund (EIF) for additional resources to support Polish small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Thanks to this agreement under the EU's SME programme COSME, the supported SME loan volume was expected to reach a total of PLN10.5 billion (EUR2.5 billion).

March 2020

Poland’s parliament on March 31 approved a coronavirus rescue package to support the economy but rejected many changes proposed by the opposition such as mandatory weekly coronavirus tests for medical workers. The lower house of parliament, the Sejm, controlled by the ruling nationalist Law and Justice (PiS) party, first approved a package offering up to PLN75 billion (USD18.07 billion) of additional budget spending on jobs and infrastructure.

March 2020

Poland’s ruling party also fast-tracked changes to the electoral code as part of the rescue package which was approved by the Czech parliament on March 31 2020 to allow seniors and those under quarantine to vote by post in a bid to press ahead with presidential elections in May 2020.

April 2020

The Polish government had decided to proceed with the presidential election scheduled for May 10 2020, sparking a new debate between the governing PiS party and the opposition on how to properly hold the vote amid the Covid-19 pandemic.

May 2020

Presidential elections did not take place due to the coronavirus. The head of Poland's electoral commission told parliament that it had 14 days to declare the new date of the presidential election.

Sources: BBC country profile – Timeline, Fitch Solutions

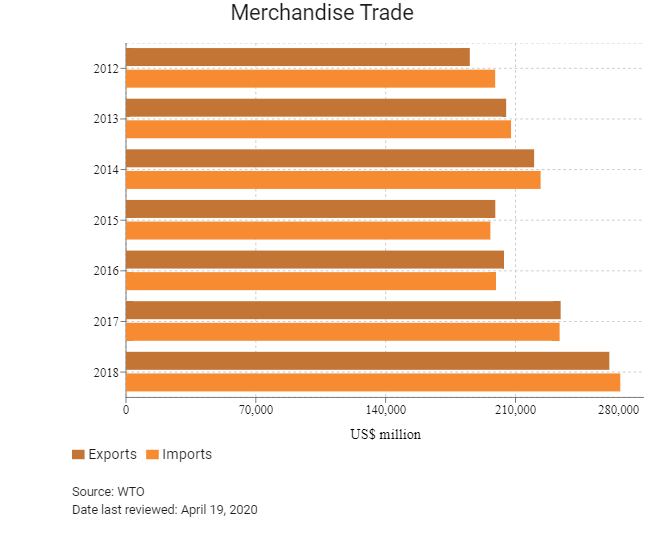

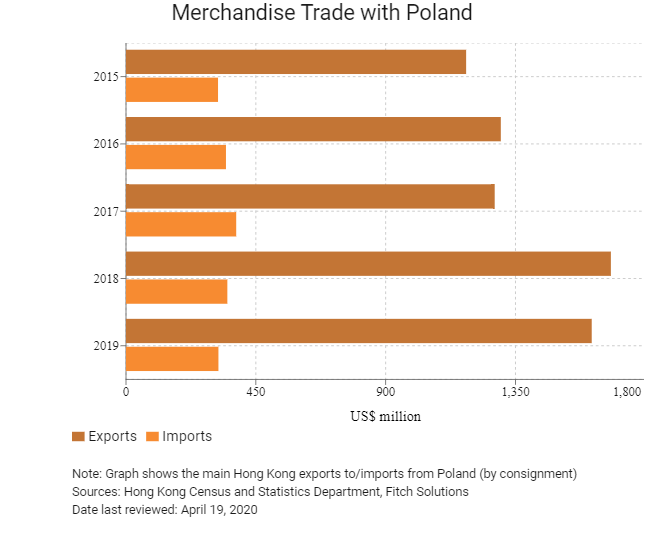

Merchandise Trade

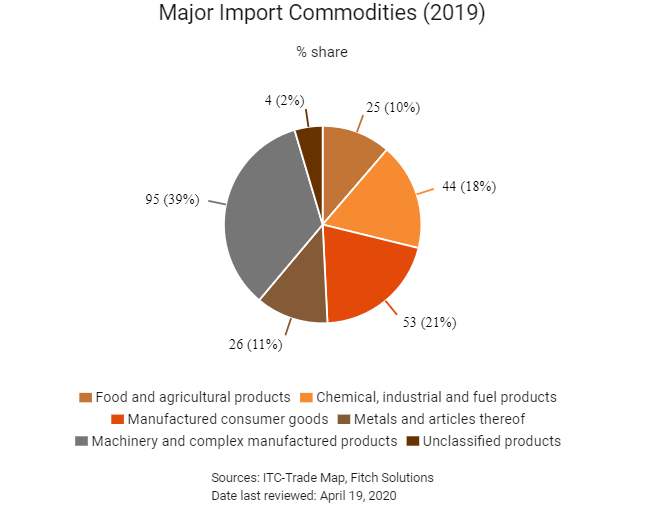

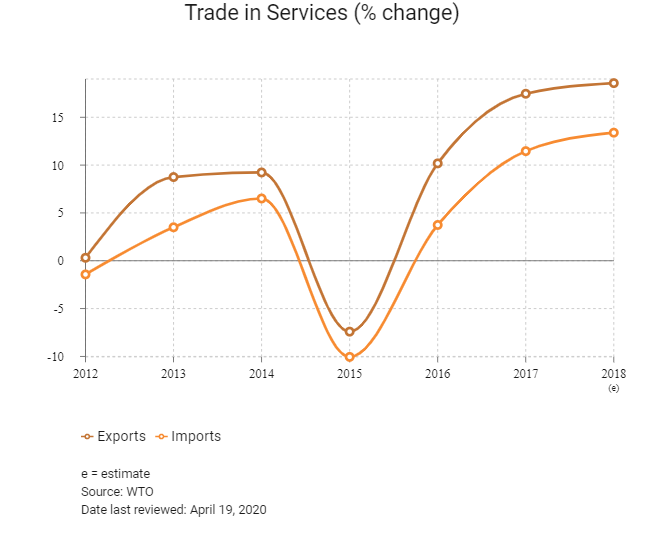

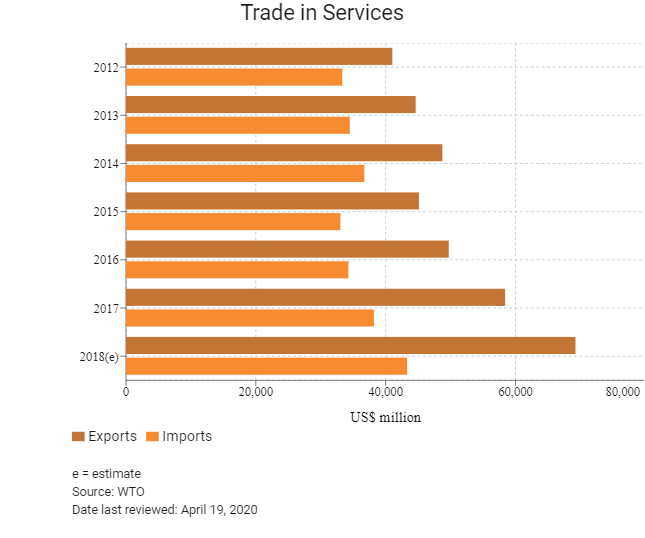

Trade in Services

- Poland has been a member of World Trade Organization (WTO) since July 1, 1995 and a member of General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) since October 18, 1967.

- Poland has been a member of the EU since 2004. All EU member states are WTO members.

- Trade flows are largely unhindered by import tariffs, which at 1.5% on average, are among the lowest in the world, and non-tariff barriers to trade are minimal. There are no currency controls or import substitution policies that would burden importers, and trade standards and policies adhere to EU rules.

- Poland applies the EU's Common Customs Tariff, which means that goods manufactured and imported from within the EU are not subject to customs charges. The average tariff rate for EU states is just 1%, which is among the lowest globally, although goods imported from outside the EU will incur duties of 0-17%.

- The EU has imposed various anti-dumping measures on a wide range of products, predominantly in the areas of textiles, machine parts, steel, iron and machinery on goods coming from Mainland China and a few other Asian nations to protect domestic industries. Currently, a number of products originating from Mainland China are subject to duties, including bicycles, bicycle parts, ceramic tiles, ceramic tableware and kitchenware, fasteners, ironing boards and solar glass. These products are of interest to Hong Kong and regional exporters. In November 2016, the European Commission (EC) imposed a provisional anti-dumping duty on imports of some primary and semi-processed metals from Mainland China. The rate of duty is between 43.5% and 81.1% of the net free-at-Union-frontier price before duty depending on the company. In the same vein, the rate of duty for similar goods from Belarus is 12.5% of the net free-at-Union-frontier price before duty. As of end December 2018 (latest data available), the EU did not apply any anti-dumping measures on imports from Hong Kong.

- In 2016, the EC introduced an import licensing regime for steel products exceeding 2.5 tonnes. The regulation will be active until May 15, 2020.

- In February 2018, the Polish government officially enacted its Act on Electromobility and Alternative Fuels. The Act will introduce excise duty exemptions for electric vehicles (EVs), tax exemptions for companies using EVs, a new government procurement plan based on electrifying its government fleet as well as support for charging infrastructure development. This reform will position Poland well in terms of attracting investors that are higher up on the automotive and technology value chains.

- Value-added tax (VAT) is charged at a rate of 23% on the sale of goods, services and imports; 0% applies to exports and supplies of goods within the EU. Reduced rates are applicable to specified goods and services indicated in the VAT Act, such as food, agricultural products and medical equipment.

- In April 2015, the Polish parliament amended the pharmaceutical law, restricting exports of medicinal products from the country. The amendment also introduced strict reporting obligations for marketing authorisation holders and warehouses.

Sources: WTO – Trade Policy Review, Fitch Solutions

Multinational Trade Agreements

Active

- Poland has been a member of the WTO since July 1, 1995 and the EU since 2004.

- The EU: The EU is a political and economic union of 28 member states that are located primarily in Europe. As an EU member, Poland applies the EU Common Customs Tariff and enjoys tariff-free trade within the EU. Within the Schengen Area, passport controls have been abolished. A monetary union was established in 1999 and came into force in 2002. It consists of 19 EU member states that use the euro; however, Poland still maintains its own currency.

- EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA): This agreement was provisionally applied as of September 21, 2017. The agreement is expected to boost trade between partners as CETA removes all tariffs on industrial products traded between the EU and Canada. CETA also opens up government procurement. Canadian companies will be able to bid on opportunities at all levels of the EU government procurement market and vice versa, though some sectors are restricted. The agreement will only enter into force fully and definitively when all EU member states have ratified the agreement.

- EU-Europe Free Trade Association (EFTA): This agreement includes Switzerland, Norway, Liechtenstein and Iceland. The European Economic Area (EEA) unites the EU member states and the four EEA EFTA states (Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland) into an internal market governed by the same basic rules. The agreement on the EEA, which entered into force on January 1, 1994, aims to enable goods, services, capital and persons to move about freely in the EEA in an open and competitive environment. This concept is referred to as the four freedoms.

- EU-Turkey: The customs union within the EU provides tariff-free access to the European market for Turkey, benefitting both exporters and importers.

- EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) : In July 2018, the EU and Japan signed a trade deal that promises to eliminate 99% of tariffs that cost businesses in the EU and Japan nearly EUR1 billion annually. According to the European Commission, the EU-Japan EPA will create a trade zone covering 600 million people and nearly a third of global GDP. The EPA was finalised in late 2017 after four years of negotiation and came into force on February 1, 2019 after the EU Parliament ratified the agreement in December 2018. The total trade volume of goods and services between the EU and Japan is estimated at EUR86 billion. The key parts of the agreement will cut duties on a wide range of agricultural products and it seeks to open up services markets, particularly financial services, e-commerce, telecommunications and transport. Japan is the EU's second biggest trading partner in Asia after Mainland China. EU exports to Japan are dominated by motor vehicles, machinery, pharmaceuticals, optical and medical instruments and electrical machinery.

- EU-South African Development Community (SADC) EPA (Botswana, Lesotho, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa and eSwatini): An agreement between EU and SADC delegations was reached in 2016 and is fully operational for SADC members following the ratification of the agreement by Mozambique. The remaining six members of the SADC now included in the deal (the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Zambia and Zimbabwe) are seeking economic partnership agreements with the EU as part of other trading blocs – such as with East or Central African communities.

Ratification Pending

EU-Central America Association Agreement (Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Belize and the Dominican Republic): An agreement between the parties was reached in 2012 and is awaiting ratification (29 of the 34 parties have ratified the agreement as of October 2018). The agreement has been provisionally applied since 2013.

Under Negotiation

- EU-Australia: The EU, Australia's second largest trade partner, launched negotiations for a comprehensive trade agreement between the two parties. Bilateral trade in goods between the two has risen steadily in recent years, reaching almost EUR48 billion in 2017, while bilateral trade in services added an additional EUR27 billion. The negotiations aim to remove trade barriers, streamline standards and put European companies exporting to or doing business in Australia on equal footing with those from countries that have signed up to the Trans-Pacific Partnership or other trade agreements with Australia. The Council of the EU authorised opening negotiations for a trade agreement between the EU and Australia on May 22, 2018.

- EU-United States (Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership): This agreement was expected to increase trade and services, but it is unlikely to pass under the current administration in the United States against the backdrop of rising global trade tensions.

- EU-West Africa EPA: West Africa is the EU's largest trading partner in sub-Saharan Africa. EU’s main imports from West Africa consist mainly of fuels and food products while its exports to West Africa consist of processed foods, machinery and chemicals and pharmaceutical products. The EU has initialed an EPA with 16 West African states. Until the adoption of the full regional EPA with West Africa, EPAs with Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana have been entered into provisional application on 3 September 2016 and 15 December 2016 respectively.

- EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement (FTA): In July 2018, the EU and Vietnam agreed on final texts for the EU-Vietnam FTA and the EU-Vietnam Investment Protection Agreement. In Q219 the conclusion of the agreement in the European Parliament was delayed until 2020 as a result of Brexit proceedings and EU parliamentary elections.

Sources: WTO Regional Trade Agreements database, Fitch Solutions

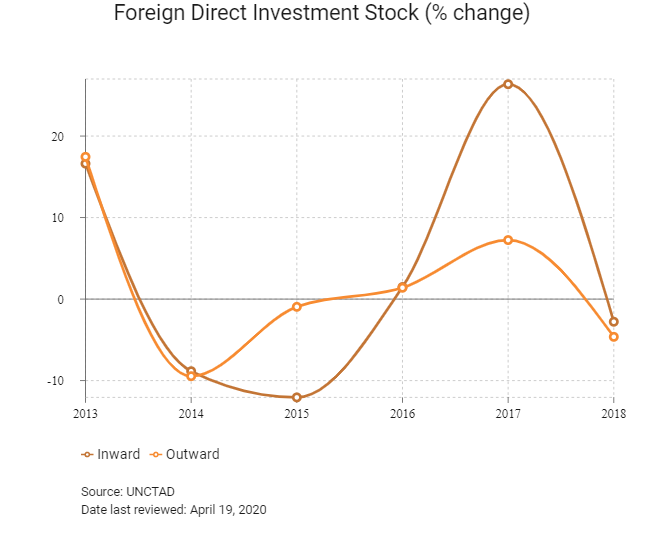

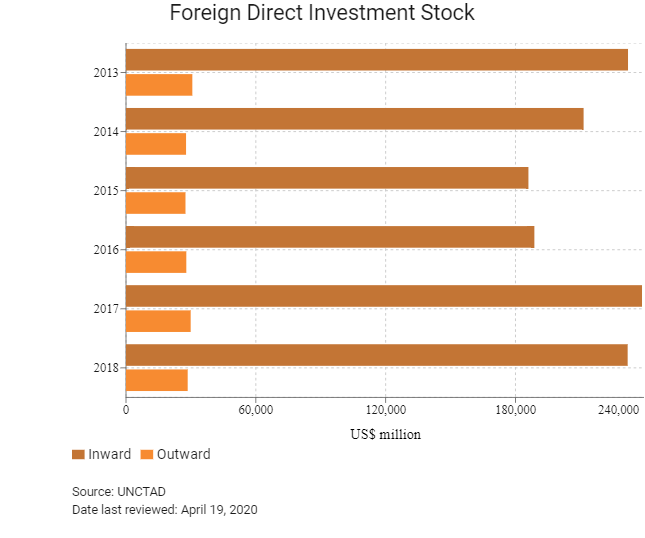

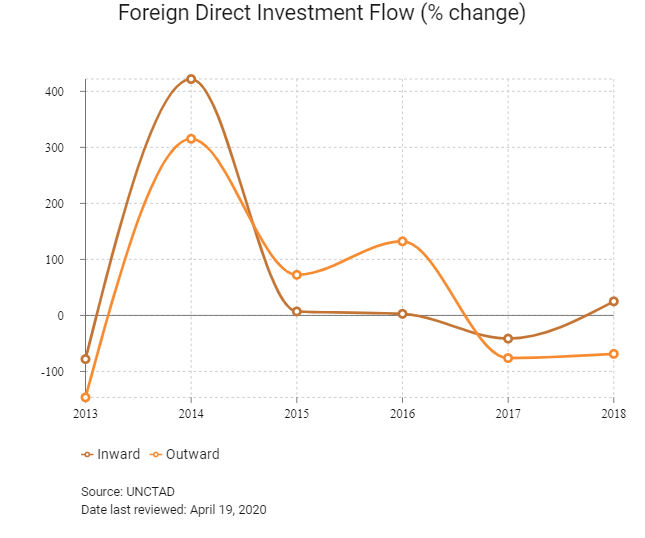

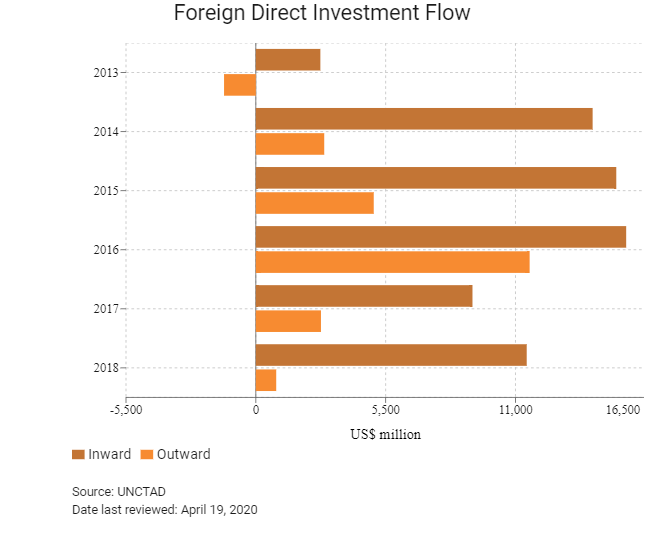

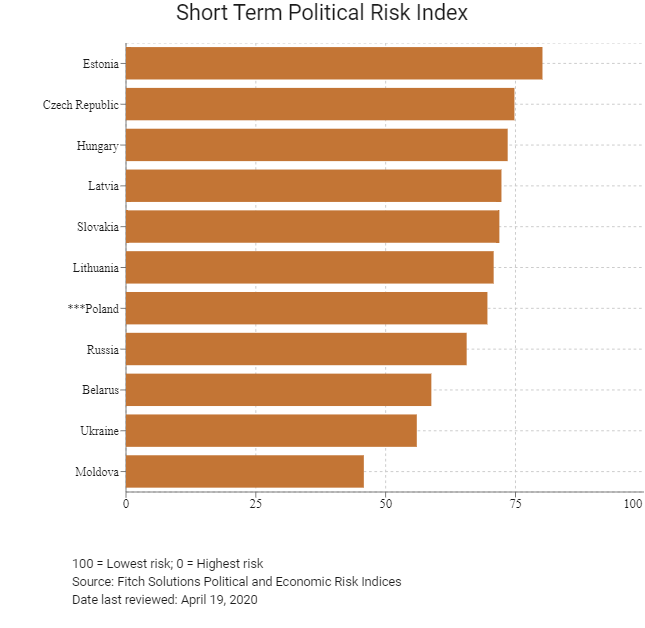

Foreign Direct Investment

Foreign Direct Investment Policy

- There are a variety of Polish agencies involved in investment promotion. The Economic Development Ministry has two departments involved in investment promotion and facilitation: the Large Investment Support Department and the International Relations Department. The Foreign Affairs Ministry promotes Poland's foreign relations, including economic relations, and along with the Polish Chamber of Commerce organises missions of Polish firms abroad and hosts foreign trade missions to Poland. Starting February 2017, the Polish Investment and Trade Agency (PAIH) replaced the Polish Information and Foreign Investment Agency as the main institution responsible for the promotion and facilitation of foreign investment. The rebranding is connected with the expansion of the scope of the agency's activities. Apart from providing services to investors in the country, PAIH will support Polish investors abroad. The agency will operate as part of the Polish Development Fund, which integrates government development agencies. PAIH will coordinate all operational instruments, such as diplomatic missions, commercial fairs and programmes dedicated to specific markets and sectors, as well as promote the Polish economy and attract foreign investors to the country. These services are available to all investors.

- Related laws and regulations on foreign investment are well established; however, some restrictions still remain on foreign direct investment (FDI), such as limits on foreign ownership and business activity in core sectors. The Act on the Control of Certain Investments entered into force in 2015 and provides for the screening of acquisitions in energy generation and distribution; petroleum production, processing and distribution; telecommunications and the manufacturing and trade of explosives, weapons and ammunition.

- Poland's support for foreign investors is generally sectoral in focus; regional support is provided in the context of sectoral investments. Any company investing in Poland, either foreign or domestic, may apply for assistance from the Polish government. Foreign investors have the potential to access grants and certain incentives. There are 14 special economic zones (SEZs) located throughout Poland on major supply chain routes. The benefits available for locating in these zones include income tax exemption, real estate tax exemption, competitive land prices and close access to high-quality local suppliers.

- Foreign ownership is permitted, with the exception of some sectors that are designated as strategic sectors. Polish law restricts foreign investment in land and real estate. Polish law limits non-EU citizens to 49% ownership of a company's capital shares in the air transport, energy, radio and television broadcasting and airport and seaport operations sectors.

- Licences and concessions for defence production and management of seaports are granted on the basis of national treatment for investors from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries.

- Polish law restricts foreign investment in land and real estate. Since Poland's EU accession, foreign citizens from EU member states and EFTA countries (Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland) do not need permission to purchase non-agricultural real estate or to acquire or receive shares in a company owning non-agricultural real estate in Poland. Land usage types, such as technology and industrial parks, business and logistic centres, transport, housing plots, farmland in SEZs, household gardens and plots up to two hectares are exempt from agricultural land purchase restrictions. Citizens from countries other than the EU and EFTA are allowed to purchase an apartment, 0.4 hectares of urban land, or up to half a hectare of agricultural land with building restrictions and restrictions on eligibility for government support programmes. In order to make large commercial real estate purchases, foreign citizens must obtain a permit from the Ministry of Interior (with the consent of the Defence and Agriculture Ministries), pursuant to the Act on Acquisition of Real Estate by Foreigners. Laws to restrict farm land and forest purchases came into force on April 30, 2016.

Sources: WTO – Trade Policy Review, government websites, Fitch Solutions

Free Trade Zones and Investment Incentives

Free Trade Zone/Incentive Programme | Main Incentives Available |

| There are 14 SEZs located throughout Poland on major supply chain routes | - Exemption from custom duties and VAT - Competitive land prices - Real estate tax and Income tax exemption - Good access to high quality local suppliers - The amount of government aid available to investors is subject to the EU's aid intensity programme, whereby projects in less developed regions benefit from incentives of up to 50% of the costs of new investment, with this percentage falling to 10% in the most developed region, Warsaw. - Investment grants of up to 50% of investment costs (or 70% for small or medium-sized enterprises) are available. Grants for research and development and other activities, such as environmental protection, training, logistics or use of renewable energy sources, are also available. |

Sources: US Department of Commerce, Fitch Solutions

- Value Added Tax: 23%

- Corporate Income Tax: 19%

Sources: Poland National Revenue Administration, Fitch Solutions

Important Updates to Taxation Information

- Poland's tax regime is applied evenly to both resident and non-resident businesses. In June 2018 new regulations concerning SEZs entered into force. The new rules significantly change the situation for investors planning to get income tax incentives in relation to new investment projects. Zonal permits are no longer issued by the authorities, but entities may apply for decisions based on the new regulations. The biggest change in the SEZs system is its availability, as obtaining a tax incentive does not depend on the location of the new investment.

- With effect from January 1, 2019, a lower corporate income tax rate is in force for companies whose revenues in a given fiscal year are lower than EUR1.2 million. Under certain conditions, companies that start operations from 2019 will be eligible to apply a lower corporate tax rate of 9%, compared to the standard corporate income tax rate of 19%.

- As of January 2019, an exit tax was introduced, which refers to taxation of unrealised profits related to moving one's assets to another country. The exit tax may be applicable to foreigners working in Poland and emplyees leaving Poland to work abroad.