Hungary

Grant Thornton is one of the leading business advisers of independent assurance, tax and advisory services that helps dynamic organisations unlock their potential for growth. Our brand is respected globally, as one of the major global accounting organisations recognised by capital markets, regulators and international standards setting bodies. As a US$4.7bn global organisation of member firms with 40,000 people in over 130 countries, we have the scale to meet your changing needs, as well as the insight and agility that helps you to stay one step ahead. Privately owned, publicly listed and public sector clients come to us for our technical skills and industry capabilities but also for our different way of working. Our partners and teams invest the time to truly understand your business, giving real insight and a fresh perspective to keep you moving. Together with our International Business Centres (IBCs), we can draw on the resources and supports from Grant Thornton’s global network, deep knowledge of the latest regulations, techniques and business practices in major jurisdictions worldwide. Whether a business has domestic or international aspirations, Grant Thornton can help you unlock your potential for growth.

PwC China/Hong Kong is the largest professional services firm in China. PwC’s network firms operate in 157 countries with more than 195,000 partners and staff including almost all of the territories under the Belt and Road Initiative. PwC provides a full range of advisory, consulting, tax and assurance services, including but not limited to valuation strategy services, financial modelling, mergers and acquisitions advisory, investment and project structuring, financial due diligence, tax planning and due diligence and strategic advice to investors in identifying and building capabilities required for this initiative. These successful developments of the Belt and Road Initiative will invariably require some or all of the professional services noted above. PwC will be able to provide local knowledge and expertise in most of the territories under the Belt and Road Initiative.

Crowe Horwath (HK) CPA Limited is a full-service CPA member firm of Crowe Horwath International and is based in Hong Kong. We provide a comprehensive range of professional services including audit, tax, risk management, merger and acquisition, trust, estate planning, data security and IT audit, ESG and sustainability consulting, business and property valuation, human resources, executive coaching and business advisory services to clients in the Greater China region.

As one of the pioneer accounting firms exploring the China market, we are accustomed to the culture, economy and business environment in Hong Kong and Mainland China. We have also built up strong connections with both the public and private sectors in China. Together with the support from member firms of the top 9 accounting network globally, we assist Chinese enterprises to access the international markets and at the same time help our international clients to establish presence in the vast China market.

BDO Limited is the Hong Kong member firm of BDO International Limited, the fifth largest worldwide accountancy network with over 1,300 offices in more than 150 countries and almost 60,000 people, including 31 offices in Mainland China as well as covering all the major countries and cities within the One Belt One Road.

BDO Limited has 50 directors and a staff of over 1,000 in Hong Kong. Our professional services include assurance, taxation, business recovery, forensic accounting, litigation support, matrimonial advisory, risk advisory and business services. Our professionals are well-versed in all accounting and auditing standards, tax and investment regulations prevailing in Hong Kong, Mainland China as well as other major countries. We conform to the highest international standards in a full range of professional services.

Citi, a leading global bank, has approximately 200 million customer accounts and does business in more than 160 countries and jurisdictions. Citi provides consumers, corporations, governments and institutions with a broad range of financial products and services, including consumer banking and credit, corporate and investment banking, securities brokerage, transaction services, and wealth management.

Central and Eastern European Countries (CEECs) have played an increasingly pivotal role in China’s foreign policy considerations and are key partners to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Cash-rich Chinese white knights have become highly sought-after by many struggling but promising CEE businesses, while generous funding for mega government-to-government (G-to-G) infrastructure projects and seed capital for start-ups are also providing valuable impetus to rejuvenate the CEE economy and restore its industrial and commercial prowess.

CEECs as a Key Partner to “16+1” and BRI

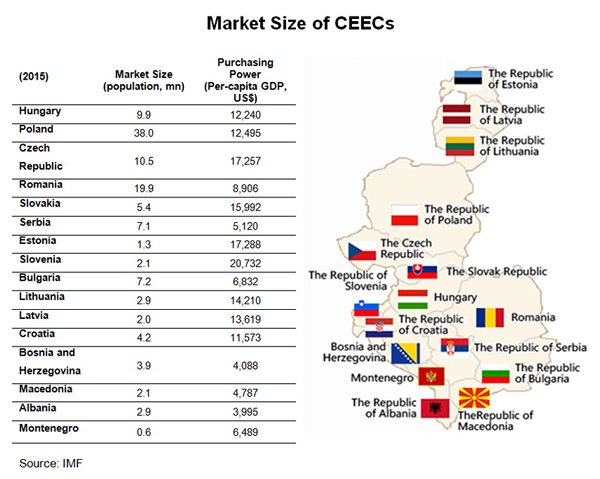

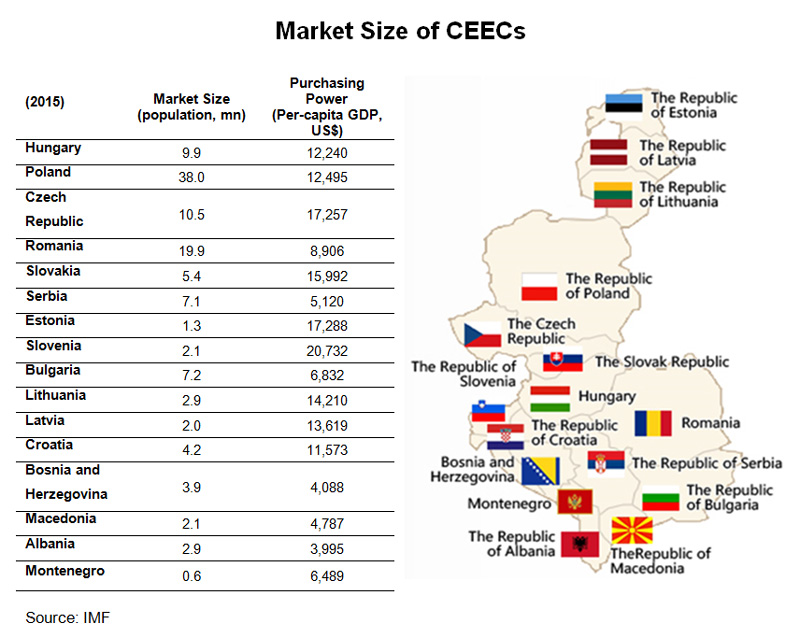

In 2011, China revived its co-operation with a group of 16 Central and Eastern European countries (CEECs), namely Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia and Slovenia. In 2012, the first meeting at a heads of government level was held in Warsaw, marking the official launch of the 16+1 format or mechanism under which China provides preferential financing to support investment projects that use Chinese inputs such as equipment “through business means”.

Since its establishment, the 16+1 format has not only been well-received by member countries, but is increasingly used as a leeway to allow cash-strapped CEECs to sidestep possible violations of EU restrictions on sovereign debt levels. Strengthening Sino-CEEC co-operation and connectivity is also conducive to the successful implementation of the BRI, which aims to facilitate and promote greater integration among the 60-plus countries along the Belt and Road. CEECs, providing a strategic link between Asia and West Europe, are vital to the success of the BRI.

Sino-CEEC Investment and Trade Continue to Blossom

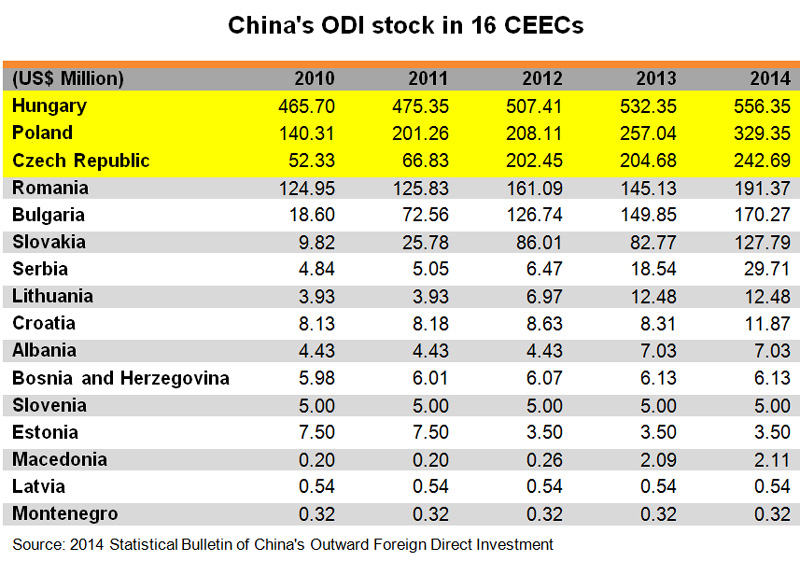

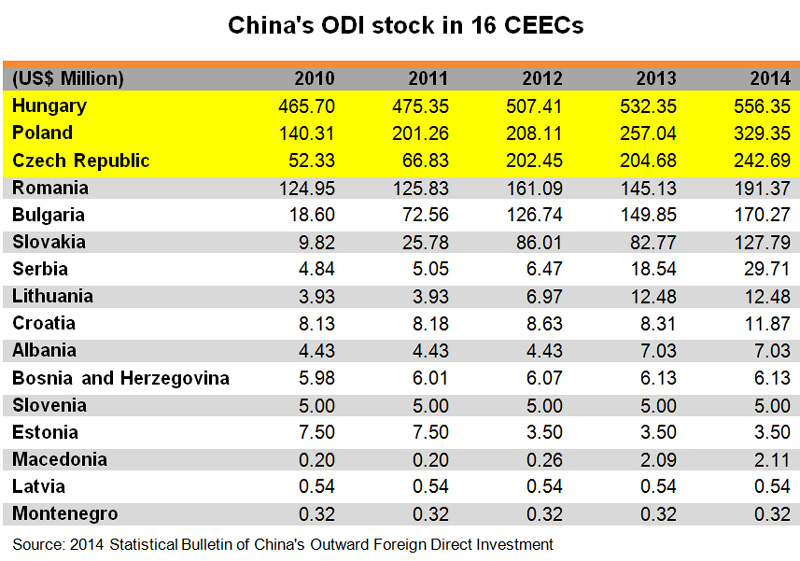

Banking on good Sino-CEEC relations and China’s implementation of a “going out” strategy at the turn of the century, Chinese investors have been investing in projects across the CEECs for some time. China’s outbound direct investment (ODI) in CEECs has been flourishing, while bilateral trade has also blossomed.

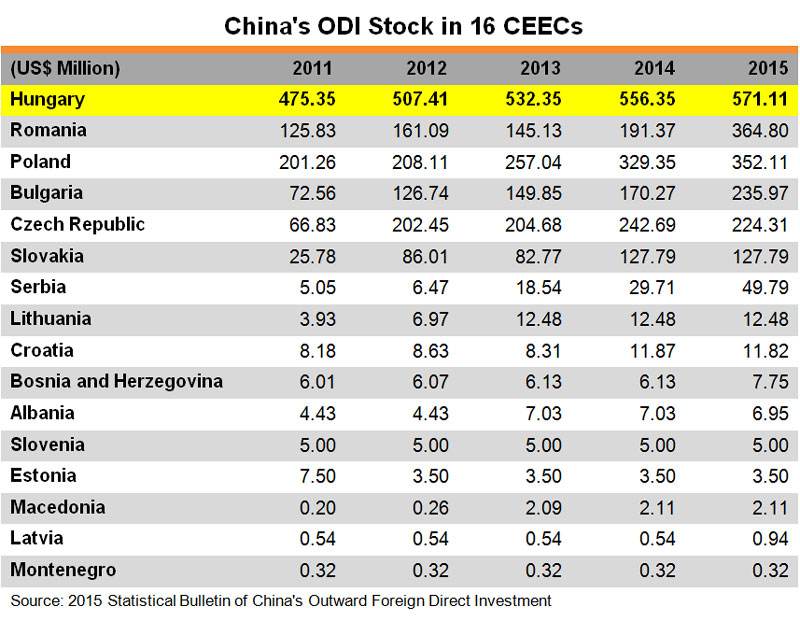

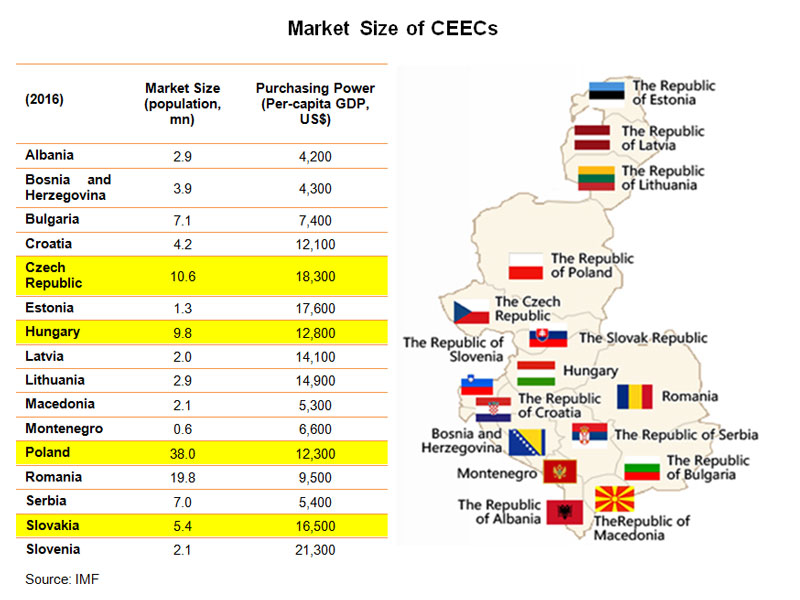

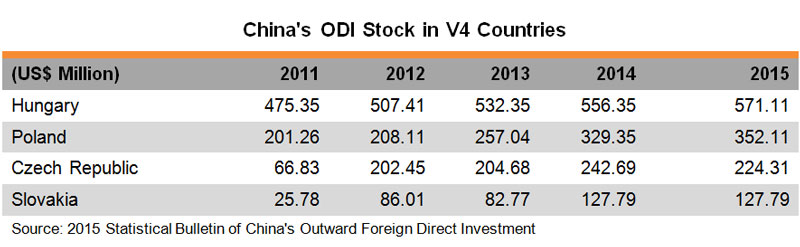

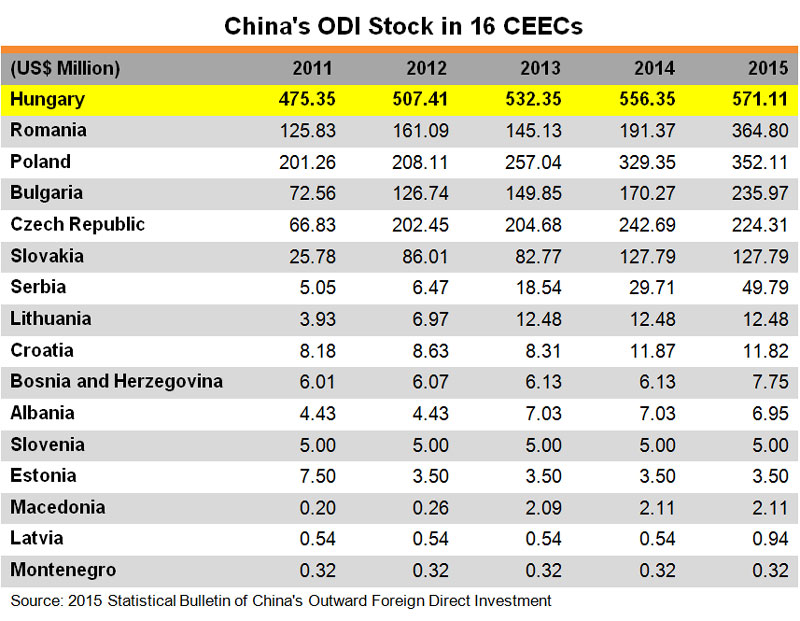

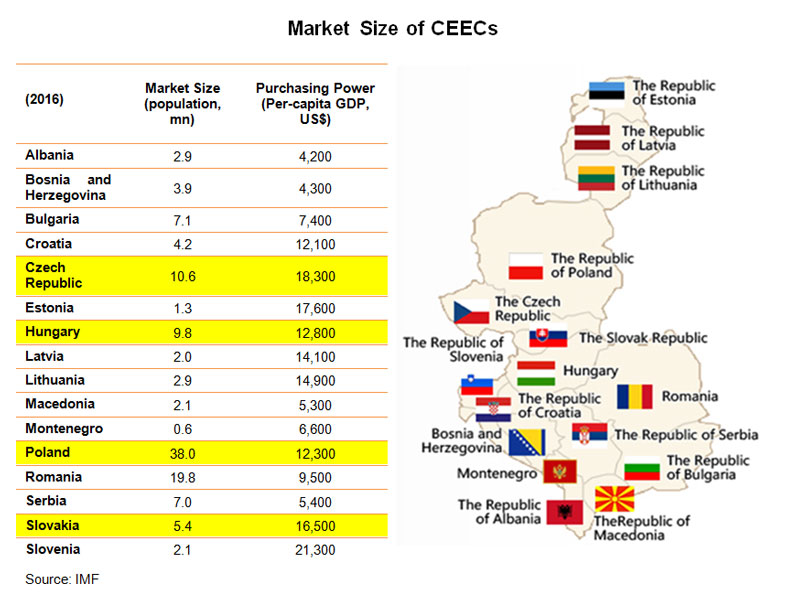

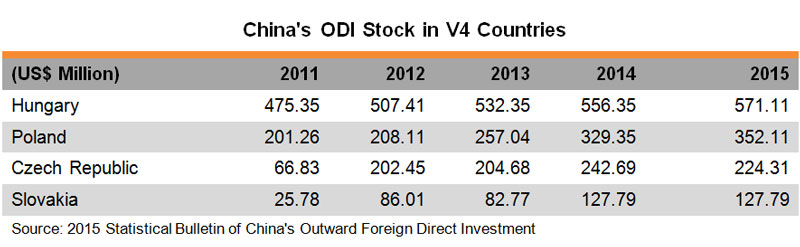

In the five years ending 2014, China’s ODI to CEECs grew by nearly 100% from US$853 million to US$1.7 billion. Among the 16 CEECs, three countries – namely Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic – accounted for more than two-thirds of the total, followed by Romania, Bulgaria and Slovakia, which together accounted for another 30%.

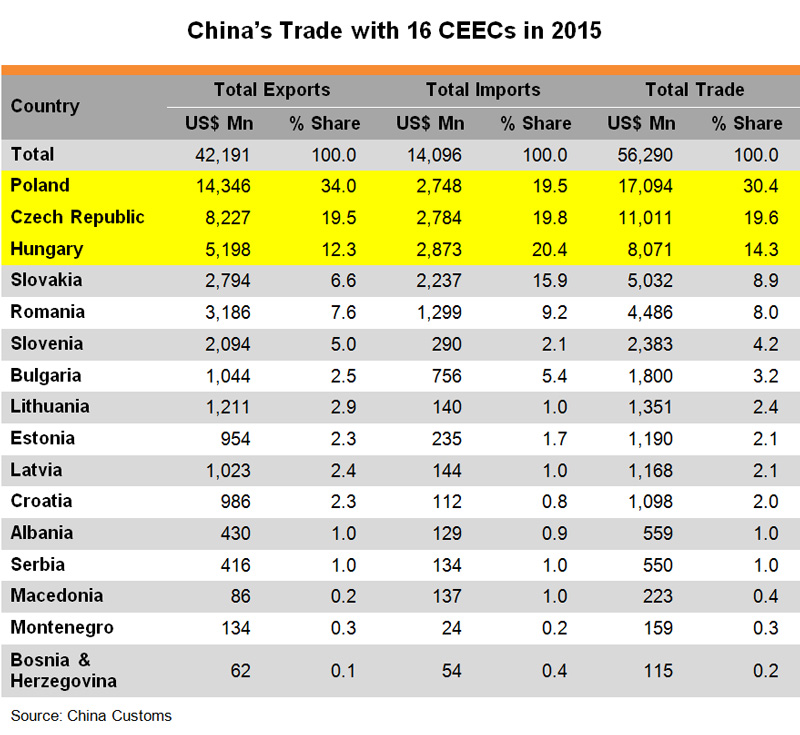

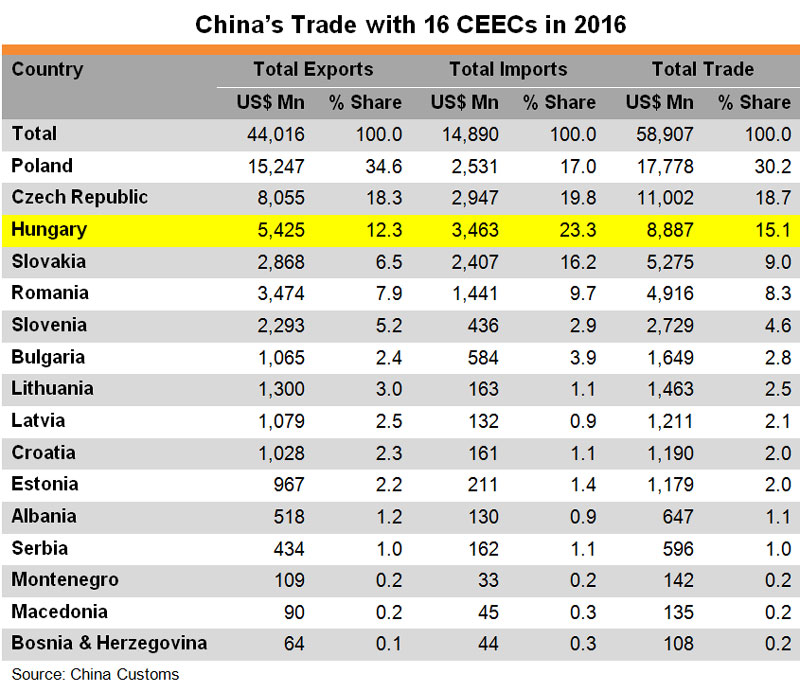

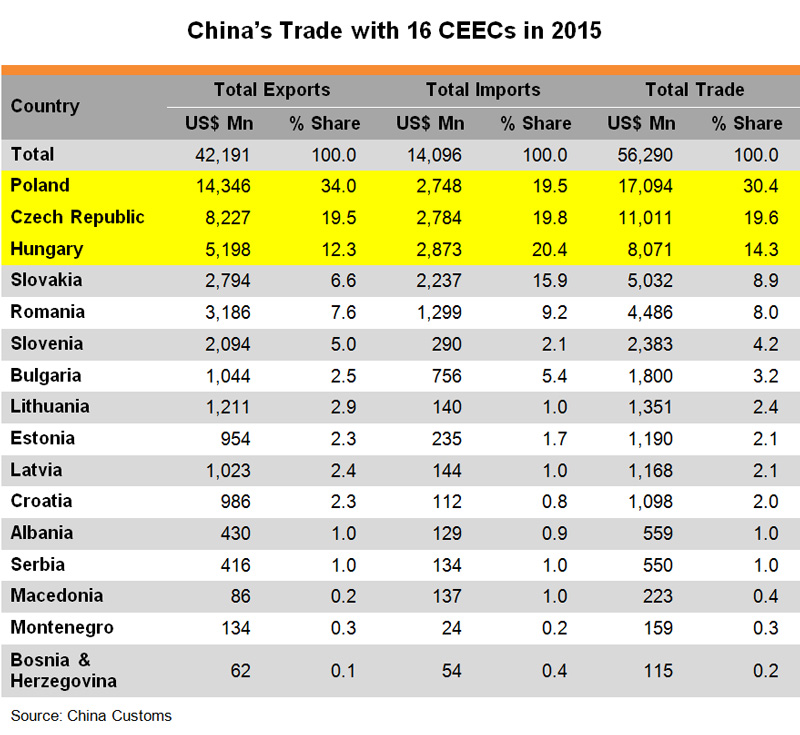

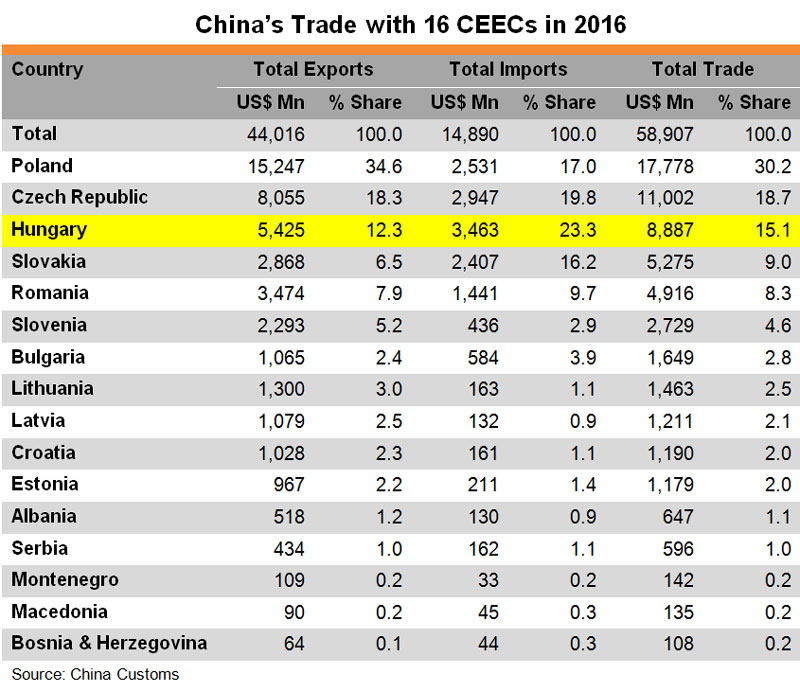

Trade between China and CEECs has remained unbalanced, however. In 2015, China’s exports were nearly twice the size of its imports from the 16 countries. This huge trade imbalance has provided a rallying cry for a new development model featuring enhanced connectivity with greater investment in infrastructure such as railroads, highways, tunnels, bridges, power plants, electric grids, industrial and logistic parks, seaports and airports.

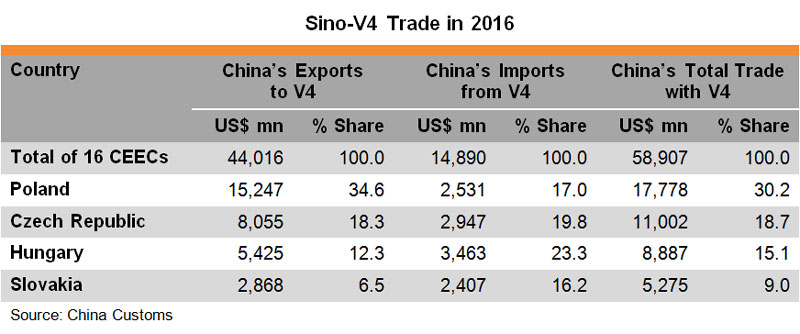

In fact, there is already a balancing trend in Sino-CEEC trade, due mainly to an increase in demand for products such as metals, minerals, chemicals and food and beverages from CEECs. Between 2011 and 2015, China’s trade with 16 CEECs grew by a mere 6.4% from US$52.9 billion to US$56.3 billion. The country’s exports to CEECs increased in that period by only 5.0% but imports from the 16 countries saw a 10.5% expansion. Similar to the pattern seen in China’s ODI to CEECs, Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary were China’s top three trading partners among the 16 CEECs, accounting for more than 64% of all Sino-CEEC trade in 2015.

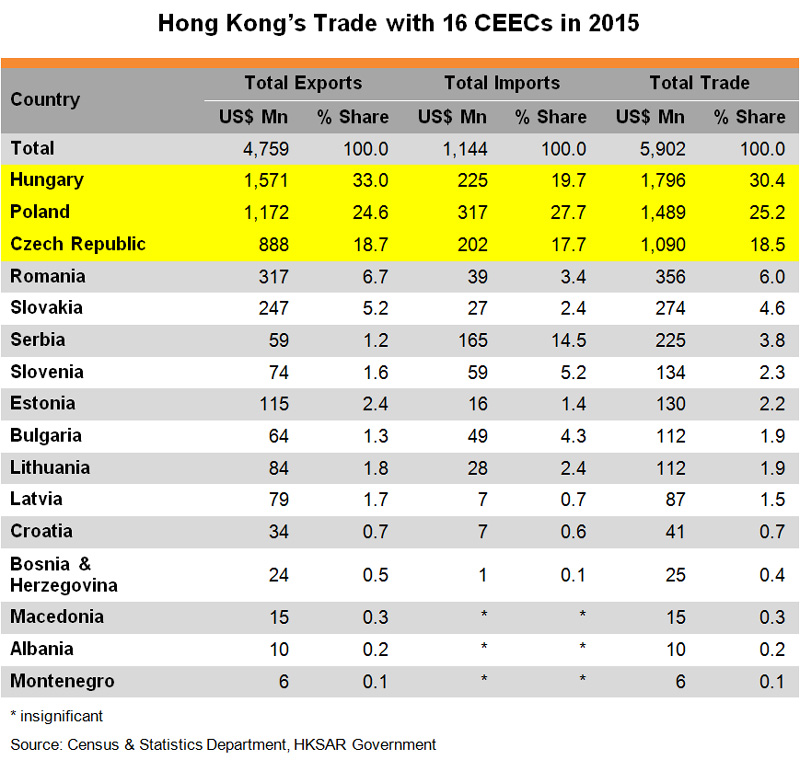

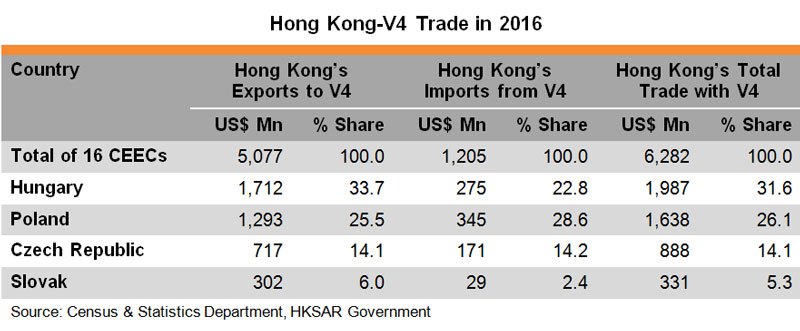

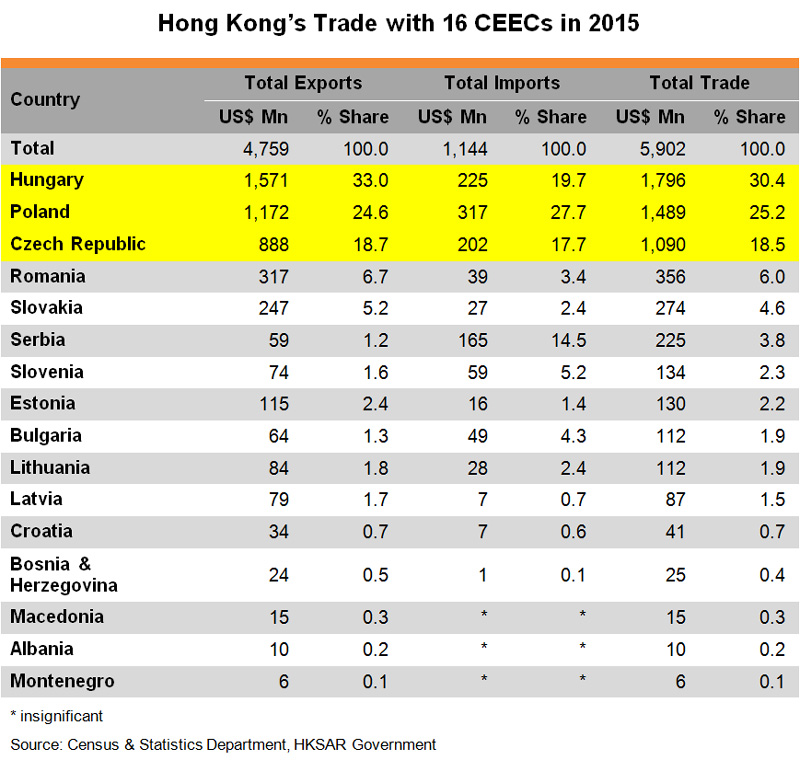

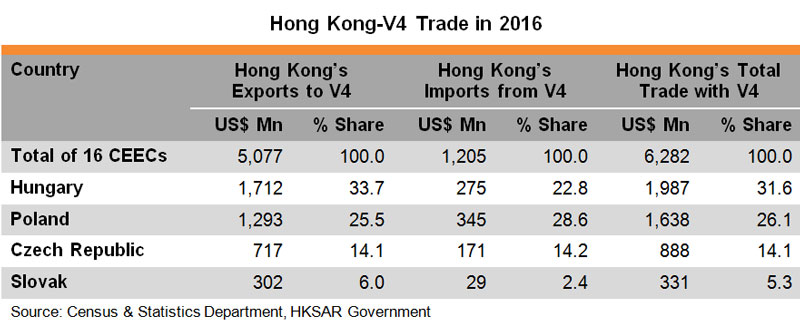

Though Hong Kong’s investment in the 16 CEECs is far from significant, its trade pattern is consistent with Sino-CEEC trade overall, with Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic accounting for nearly 75% of Hong Kong’s total trade with the 16 CEECs in 2015. Boasting a similar year-on-year growth of 24% in the first half of 2016, compared to the 13% regional average, Hungary and Poland are not only sizeable markets among the CEECs, but fast-growing export destinations for Hong Kong traders.

Looking ahead, better alignment of the 16+1 format with the BRI is expected to provide new opportunities to widen and deepen trade and investment co-operation between China and the CEECs. Moving from being export destinations to becoming investment partners in production, technology, finance and infrastructure development, CEECs are likely to see new trade patterns with China, involving higher value-added goods and services with higher technology content.

While different good and services may experience different fortunes in the CEECs, electronics – Hong Kong’s largest merchandise export earner – has fared well in the region. This is especially the case in countries where electronics manufacturing outsourcing clusters are becoming increasingly prominent in the face of rising production costs in other more distant production bases and in light of a greater need for proximity to key markets and better inventory management.

To this end, Hungary has been specialising in the production of transport vehicles since Soviet times, and boasts a long history of auto parts and electronics manufacturing. Hungary is the largest electronics producer among the CEECs, representing some 30% of the region’s total electronics output. Meanwhile, the Czech Republic is often regarded as the most successful Central and Eastern European country in terms of attracting foreign investment, thanks to its strong automotive cluster. For its part, Poland has the largest domestic market and ranks high in terms of manufacturing and automation.

Examples of BRI in Action in the CEECs

While most, if not all, of the CEECs are supporters of the BRI, some have shown greater participation than others. For instance, Poland, with its well-developed industrial market and logistical importance (it is estimated that 25% of all road transport in Europe is operated by Polish companies) has not only established a strategic partnership with China but is also a founding member of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) – the only CEEC joining the bank so far.

As an important conduit linking Asia and Western Europe in the BRI, in 2013 a high-speed railway started operating from Chengdu, the provincial capital of Sichuan province, in Southwest China, to Łódź, in Poland. The freight train takes only 10-12 days to ship goods from China to Poland, twice as fast as sea transport. Goods arriving in Łódź can then be transported to warehouses or customers in London, Paris, Berlin and Rome via Europe’s rail and road networks.

So far, railway lines for container trains have opened up in 16 Chinese mainland cities, heading to 12 European cities including many CEECs such as Łódź in Poland, Pardubice in the Czech Republic and Košice in Slovakia. Last year, Sino-European freight trains made a total of 815 trips, representing a year-on-year increase of 165%.

To better enhance co-operation between companies from both countries, Poland started offering consular services in Chengdu, while the Łódź government has also set up an office in the city. Such cooperation at sub-national levels has been institutionalised and increasingly offers a best-practice way forward in Sino-CEEC relations.

Meanwhile, Hungary – the first European country to sign a memorandum of understanding (MoU) on BRI co-operation with the Chinese mainland – has also signed deals to build a high-speed rail line between Budapest, its capital, and Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. With the line expected to be completed in 2017, the 85% Chinese-financed project will shorten the travel time between the two capitals from eight hours to three.

As an important country in the Balkan Peninsula, Serbia became China’s first strategic partner among the CEECs, in 2009. This favorable bilateral relationship is very much focused on economic co-operation under the BRI. China’s landmark projects in Serbia include the “Mihailo Pupin” Bridge on the Danube River in Belgrade, the construction of sections of the Corridor 11 highway, and the expansion of coal mines near the “Kostolac” thermal power plant.

The further extension of the Budapest-Belgrade high-speed rail line to Skopje, the capital of Macedonia, and to Athens, the capital of Greece, will give China-bound freight trains another alternative to gain access to the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas. To achieve better synergy, China’s state-owned shipping giant Cosco has recently acquired a majority stake in the Piraeus Port Authority, which complements the 35-year concession to operate Piers II and III at Piraeus port it acquired in 2009.

As the closest port in the Northern Mediterranean to the Suez Canal, Piraeus is not only one of the largest ports in the Mediterranean, but a strategic trans-shipment hub for Asian exports to Europe. China’s exports could reach Germany, for example, seven to 11 days earlier thanks to the abovementioned high-speed rail connection.

Under discussion or pending implementation are Chinese plans to invest on the construction and upgrading of port facilities in the Baltic, Adriatic, and Black Seas, with a focus on production capacity cooperation among ports and industrial and logistic parks along the coastal areas.

Hong Kong’s Unique Role in Sino-CEEC Economic Co-operation under the BRI

A new development model characterised by enhanced connectivity and greater multilateral investment will likely take Sino-CEEC economic co-operation to a higher level. The balancing trend in Sino-CEEC trade, plus the CEECs’ ongoing improvements to industrial capacity and logistical accessibility are highly conducive to the successful implementation of BRI.

Investment opportunities linked to the BRI can include cooperation in logistics along and beyond the Eurasian landbridge which directly connects Asia and Europe. Maritime finance, infrastructure bidding, project management and financing are all highly sought-after by project owners looking for competitive funding/co-operation options and Asian investors looking for more lucrative investment opportunities under Europe’s low interest-rate environment.

With about 60% of Chinese ODI being directed to, or channelled through, Hong Kong, the city, as a regional financial centre in Asia, will continue to be the bridgehead for Chinese mainland enterprises exploring “going out” through investing in greenfield schemes and joint investment projects. These may include smart cities/factories incorporating digital processes that use the Internet of Things (IoT) and Big Data, or conducting mergers and acquisitions (M&As) to reinvigorate companies, or even whole industries. Hong Kong is therefore ideally placed to help enterprises from CEECs look for investment partners from Asia, especially the Chinese mainland.

Possessing definite advantages and extensive experience in helping Chinese mainland enterprises make overseas investments, Hong Kong can play a pivotal role in the expected surge in Sino-European trade and Chinese ODI to CEECs under both the 16+1 format and the BRI, which aims to help companies co-ordinate their global supply chains.

Simultaneously, Hong Kong’s extensive link to other parts of Asia and privileged free-port status, coupled with the presence of cost-effective multimodal logistics options and professional services providers, offer CEECs a wealth of opportunities to make inroads into the burgeoning Asian market. Hong Kong’s position will be further strengthened as the Second Eurasian Land Bridge takes shape and new railway routes start operating.

Viewing Hong Kong as an ideal platform and super-connector to promote their products in mainland China and other markets in Asia, more and more companies from CEECs are using trade fairs and conferences in the city to reach out to Asian buyers and partners. For instance, Poland, as the regional leader in food exports to the Chinese mainland, has run a national pavilion at HKTDC Food Expo since 2013, occupying almost 300 square metres in 2016. This trend is expected to strengthen as companies from CEECs pay more and more attention to Asia due to European markets’ lack of growth drivers such as a sizeable youth population and growing incomes.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

As a champion of Chinese investment in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), Hungary has long been an important partner for China in the latter’s “going-out” strategy. Hungary is home to the first renminbi (RMB) clearing centre in CEE – a fact that, along with the launch of the first Chinese RMB and Hungarian forint debit card in Europe, serves to highlight the country’s preeminent role in RMB internationalisation.

Hungary was also the first European country to sign a memorandum of understanding (MoU) on Belt and Road co-operation with the Chinese mainland, an indicator of the strong Asian orientation of its policies on trade and international affairs. The hallmark project of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – a 350-km high-speed railway linking the capital cities of Hungary and Serbia – will improve Hungary’s land-sea connectivity; while the increasing number of direct air cargo connections between Hungary and Belt and Road economies like Hong Kong, Qatar and Turkey is likely to enhance the country’s status as a popular trans-shipment hub in the region.

Hungary is also active in promoting inter-cultural and people-to-people exchanges with China in fields such as tourism and the arts. The inauguration of the China-CEEC (CEE Countries) Tourism Coordination Center in the Hungarian capital Budapest in 2014, and the opening of China National Tourism Administration (CNTA)’s first CEE tourism office in the city last year, are examples of the success of Sino-Hungarian co-operation. On the cultural front, the funding opportunities made possible by the Hungarian National Film Fund (MNF) are an effective booster for cinematic co-production projects.

Close Economic Partnership with China

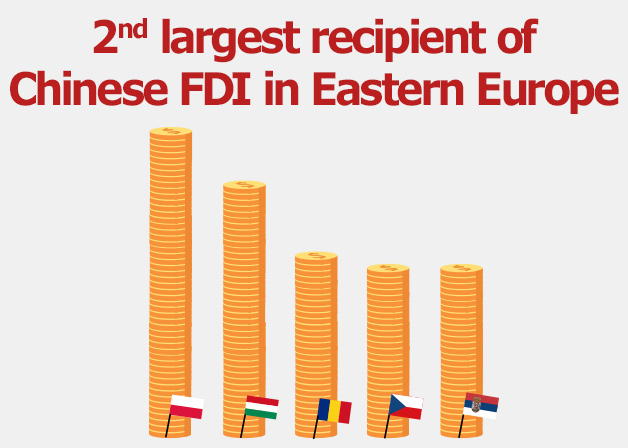

Hungary is by far the largest recipient of Chinese outbound direct investment (ODI) among the CEE members of the “16+1” co-operation framework, accounting for nearly 30% of China’s total stock of such investment in 2015. The “Opening to the East Strategy” initiated in 2010 by the Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán as a way of opening new markets in Asia after the European financial crisis coincided rather fortuitously with China’s “going-out” strategy. China’s economic and cultural exchanges with Hungary have been considerably enhanced ever since the official launch of the “16+1” framework in 2012 and the BRI in 2013.

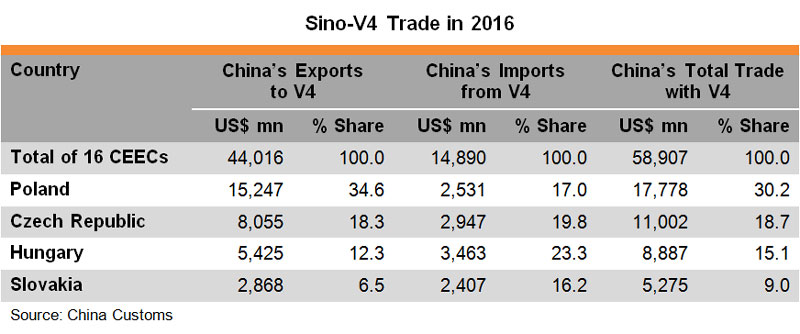

Hungary has long been one of China’s key trading partners in the CEE. In 2016, Hungary accounted for a larger share of China’s imports than any other CEE country (US$3.5bn, some 23% of the region’s total) and was behind only Poland and the Czech Republic as a CEE destination for Chinese exports (importing US$5.4bn of Chinese goods and services, 12% of the total for the region).

The ready flows of RMB liquidity from both bilateral investment and foreign trade settlements have underpinned the country’s success in promoting RMB internationalisation across Europe. In 2013, Hungary was the first CEE country to sign a currency swap agreement with the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), and in 2015 the Central Bank of Hungary (Magyar Nemzeti Bank, MNB) launched the Budapest Renminbi Initiative in conjunction with its Renminbi Programme (JRP) to foster Chinese-Hungarian economic partnerships related to the RMB-HUF (Hungarian forint) market.

Hungary is home to the regional headquarters of the Bank of China (BOC), which has operated a subsidiary in the country since 2003 and maintained a full-fledged branch there since 2014. In October 2015, Hungary was selected by BOC to launch its first RMB clearing centre in CEE, and in January 2017 the bank launched its first Chinese RMB and Hungarian forint debit card in Europe. In another significant development, Hungary became the first CEE country to issue an RMB-denominated sovereign bond in April 2016.

These multifaceted Sino-Hungarian economic ties led to Hungary becoming the first European country to sign a memorandum of understanding (MoU) on Belt and Road co-operation with the Chinese mainland in 2015. One of the first fruits of such co-operation is the flagship project of a 350-km high-speed railway between Budapest and the Serbian capital Belgrade, which will reduce the travel time between the two cities from the current eight hours to about three.

Hungary’s active participation in the BRI has been welcomed by investors such as China’s leading electric automaker BYD, which opened its first fully-owned bus plant in Europe in the northern Hungarian city of Komárom in April this year. At the same time, well-known Hungarian companies such as the world-leading Building Information Modeling (BIM) [1] software developer Graphisoft have chosen Hong Kong as their partner to grow their businesses along the Belt and Road.

With HKSARG proposing that it be a mandatory requirement for consultants and contractors to use BIM technology in their design of major government capital works projects from 2018 onwards, Graphisoft is expecting to register more clients not only from the local Hong Kong market, but also among the city’s cluster of international architecture and interior design companies that are significant players in the vibrant Asian property development market.

An Important Node on the New Silk Route

Hungary’s location has played a major part in its economic development. It is on the eastern border of the EU/EFTA Schengen Area and can therefore play a pivotal role in the regional distribution channels of CEE countries. It has close economic relationships with many of its neighbours and near-neighbours, including Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Italy, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia and Ukraine, which has made the country a popular transit point for East-West intermodal freight forwarding in the CEE region. It has also become a manufacturing outsourcing hot spot for the electronics, automotive and ICT-related industries.

Although Hungary is landlocked, it has overcome this disadvantage by developing major inland ports along the Danube River at Győr-Gönyü, Budapest, Dunaújváros and Baja, which boast an advanced infrastructure and access to the Black Sea. Furthermore, the country is at the crossroads of two Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) corridors and has the third-highest road density in Europe, enabling easy access not only to all parts of Hungary but also to its neighbouring countries.

Together with the increasing number of direct air cargo connections with Belt and Road economies such as Hong Kong, Qatar and Turkey, Hungary’s excellent transport links are enhancing its status as a popular trans-shipment hub in CEE. The amount of cargo being handled by Budapest Airport increased in 2016 by 23% from the year before to a total of more than 112,000 tonnes, and the airport is expanding to meet the increased demand. An additional cargo terminal is set to open in 2018 to cater for the rapidly growing Asia-Europe air cargo traffic, including the thrice-weekly direct cargo flights from Hong Kong operated by Luxembourg-based company Cargolux.

As part of its HUF50bn (€160mn) “BUD:2020” development programme, Budapest Airport has begun construction of a new logistics base next to Terminal 1. Preparatory works for a new major warehouse and office complex called “Cargo City”, which will handle air cargo freighters as well as belly cargo from passenger flights near Terminal 2, are expected to add an extra handling capacity of up to 200,000 tonnes per year to the airport upon completion.

The Hungarian rail network is also undergoing expansion and re-organisation as it focuses on further modernisation. Despite an ongoing EU probe into its financing, the hallmark BRI project – the Budapest-Belgrade rail link – is scheduled for completion by 2018. It is designed to improve Hungary’s connections with seaports in the Adriatic and Mediterranean Seas, including the Greek Port of Piraeus operated by China’s COSCO Shipping.

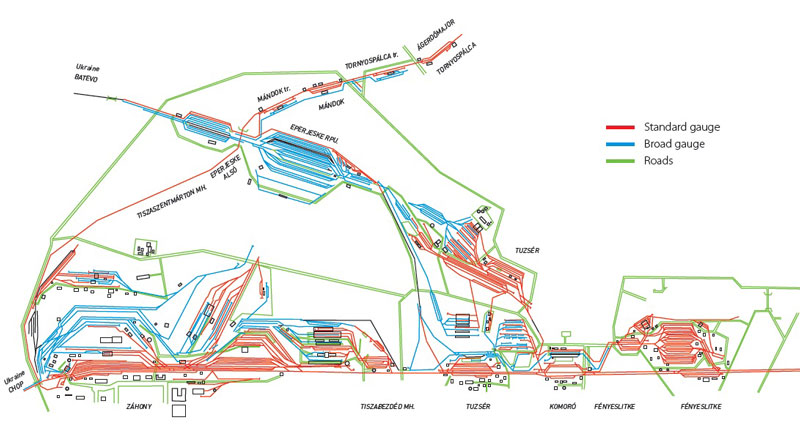

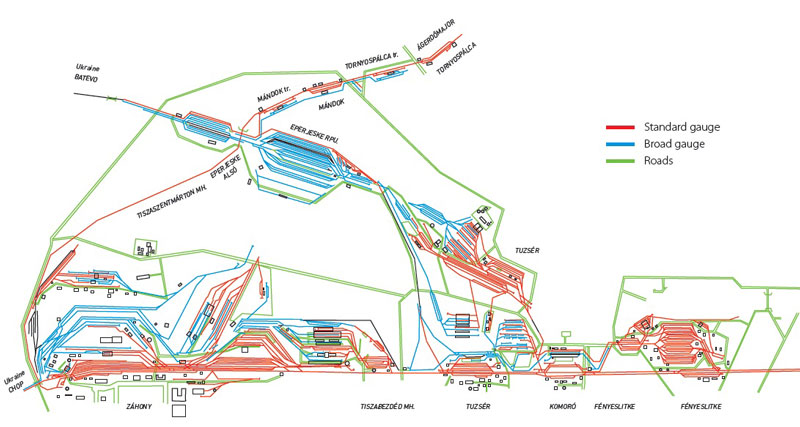

Although Eurasian rail traffic to Hungary has been somewhat disrupted by the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian conflict, Hungary’s infrastructure is considered to be very well prepared for East-West rail transport. This is especially so at the Záhony Trans-shipping Area in Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg County – once home to the largest dry port in Europe when its main responsibility was handling the commercial exchange of goods between Hungary and the former Soviet Union.

Today, Záhony is regarded as a major railway junction on the Trieste-Budapest-Kiev-Moscow-Khorgas transport corridor, trans-shipping cargo arriving from the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) countries and beyond in carriages on broad-gauge (1,520mm) railway onto standard-gauge (1,435mm) railways.

Source: Záhony Port

While products trans-shipped at Záhony nowadays are mainly bulk cargos and non-containerised goods such as metals, coals, minerals, industrial chemicals, agricultural products and raw materials for steel, tyre and plastic production, the new industrial parks being built across Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg County have already attracted a wide range of investment from multinational corporations in fields like vodka bottling, woodworking, cosmetics and LED manufacturing, creating a pool of potential users of cargo trains.

Pioneering on the Cultural Front

Hungary is also active in promoting inter-cultural and people-to-people exchanges with China in fields such as tourism and the arts. The inauguration of the China-CEEC (CEE Countries) Tourism Coordination Centre in Budapest in 2014 and the opening of China National Tourism Administration (CNTA)’s first CEE-based tourism office in the city last year are examples of the success of this Sino-Hungarian co-operation.

From the first Chinese Film Festival in Hungary in 1953 to the official premiere of Kung Fu Yoga, a Sino-Indian co-production featuring Hong Kong action star Jackie Chan at the city’s Urania National Film Theatre in April 2017, films have proved to be an important way for China to connect with the Hungarian people. The first Sino-Hungarian co-production film, China, Hungary and the Soccer, made a successful debut at the opening ceremony of the Beijing Hungarian Cultural Institute in Budapest in 2013. This, along with the funding opportunities made possible by the Hungarian National Film Fund (Magyar Nemzeti Filmalap, MNF), have boosted the co-operation between the two countries in the film industry.

The MNF, which replaced the former Motion Picture Public Foundation (MMKA), has not only revitalised the local film industry, but triggered a large influx of international film productions being shot throughout Hungary. The MNF provides financial support in the form of a post-financing cash refund of up to 25% of the eligible production expense, subject to a cultural test. It also provides professional support for the script development, project development, and production of full-length feature films, documentaries and animated films for theatrical release, as well as international marketing of completed films ready for cinema release.

As of December 2016, the MNF had granted production funding for more than 80 projects, including 18 international co-productions. Recent successful MNF-supported films include Son of Saul, which won the Cannes Grand Jury Prize in 2015 and the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar in 2016, and Sing by Kristóf Deák and Anna Udvardy, which won the Best Short Film Oscar in 2017.

As a long-term participant at the Hong Kong International Film & TV Market (FILMART), MNF’s International Sales and Distribution Department has found Hong Kong a highly effective platform for promoting Hungarian movies to Asian cinemagoers across the Chinese mainland, Japanese and South Korean markets. In this regard, it is second only to the European Film Market (EFM), which takes place every February in Berlin.

Another indication of Hong Kong’s long history of working with Hungarian filmmakers when it comes to accessing the global markets is the fact Vajna András György, the renowned Hungarian Film Commissioner started his film career in Hong Kong back in the 1970s. It was here that he founded Panasia Films (which was acquired by Golden Harvest in 1976, ultimately becoming its foreign film distribution arm).

[1] BIM is an innovative technology for bridging communications between the architecture, engineering and construction industries. It is an automated process of generating three-dimensional (3D), digital representation of building data throughout its life cycle. Apart from 3D images, BIM can potentially provide more speedy and effective analysis in respect of time and cost impacts of the design and the changes thereto, resulting in better cost control and estimation of the project.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

The Visegrad Four (V4) nations, consisting of the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia, have had remarkable success in aligning and strengthening their economies to compete and play a dominant role in the regional economy of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). They are poised to benefit most from the multifaceted alignment of the “16+1” format co-operation between Central and Eastern European countries and China) and Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The V4 countries, located in the heart of Europe, have seen rising trade and investment flows on the back of strengthened Sino-CEE co-operation and connectivity. Meanwhile, more and more V4 businesses have taken on a more global perspective in searching for new markets.

Hong Kong, given its unique combination of a vibrant capital market and a large professional services cluster with extensive global networks and affiliations, can be a crucial link in providing the important capital flows and the highly sought-after assurance to new-to-the-market V4 enterprises and investors.

Enhanced connectivity and increasingly vibrant investment flows have not only made it possible for each of the V4 countries to reinvent and reposition itself in the bigger picture of Sino-CEE co-operation, they have also provided traders and manufacturers with more possibilities in terms of regional distribution and supply chain management.

V4 Countries as Core BRI Partners in CEE

Central and Eastern European Countries (CEECs) have played an increasingly pivotal role in China’s foreign policy, and are key partners in the BRI. The “16+1” format and the BRI have multifaceted alignment as both development initiatives led by China are aiming at intensifying and expanding co-operation with the 16 CEECs, including investment in infrastructure and cooperation in industry and technology development.

Different CEECs may benefit differently from the strengthening Sino-CEEC co-operation and connectivity subject to their own development plans and national strategies. The V4, which play a leading role in the regional economy and have had remarkable success aligning and strengthening their economies to compete effectively regionally and internationally, are poised to benefit most in drawing trade and investment interest.

Representing more than half of the population and nearly two-thirds of the economic output of the 16 CEE member countries under the umbrella of the “16+1” format, the V4 are naturally important and active participants in the BRI. They offer a progressively interesting logistic alternative for shippers and their forwarders moving cargo between Asia and Western Europe, which is considered a priority to the success of the BRI as it aims to enhance the connectivity between Asia, Europe and Africa.

Banking on the good Sino-V4 relations and China’s continuous implementation of its “going out” strategy, China’s outbound direct investment (ODI) in the V4 countries has been flourishing, while bilateral trade blossoms. In the five years ending 2015, China’s ODI to the V4 grew by more than 65% from US$769mn to US$1.28bn, accounting for nearly two-thirds of China’s ODI in the 16 CEECs. Though China’s investment in V4 countries and the other CEECs is far from significant in the light of China’ total ODI, Hong Kong’s professional services providers and Chinese-funded corporate structures have quite often been involved in Sino-V4 investment deals such as M&As and takeovers.

While cash-rich Chinese investors have already made successful inroads into V4 countries by acquiring promising businesses over the past decade, more brownfield and greenfield projects, both private and public, are expected to materialise in the bloc in the coming years. Such a sustained wave of Chinese investment, plus generous funding from European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) supporting mega infrastructure projects, research and innovation and small businesses (including start-ups), will certainly give a big shot in the arm for the V4 economy to rejuvenate its industrial and commercial prowess.

Amount budgeted for period 2014-2020 Czech Republic Czech Republic, through 11 national and regional programmes, benefits from ESIF funding of €24 billion representing an average of €2,281 per person over the period 2014-2020 Hungary Hungary, through 9 national and regional programmes, benefits from ESIF funding of €25 billion representing an average of €2,532 per person over the period 2014-2020 Poland Poland, through 24 national and regional programmes, benefits from ESIF funding of €86 billion representing an average of €2,265 per person over the period 2014-2020 Slovakia Slovakia, through 9 national programmes, benefits from ESIF funding of €15.3 billion representing an average of €2,833 per person over the period 2014-2020

Source: European Commission |

Just as they are the leading recipients of Chinese ODI in CEE, the V4 countries are also the leading trading partners of China among the 16 CEECs, accounting for 73% of the total Sino-CEEC trade in 2016. Trade between China and CEECs has remained unbalanced, however. This unbalanced trade pattern – China exported nearly twice as much as it imported from the V4 countries in 2016 – has become a raison d’etre for deeper and wider Sino-V4 cooperation from mergers and acquisitions (M&As) and takeovers to higher value-added manufacturing, technology exchanges and infrastructure and real estate (IRES) projects.

The pattern of Hong Kong’s trade with V4 countries coincides with that of Sino-V4 trade – with the four countries accounting for more than 75% of Hong Kong’s total trade with the 16 CEECs in 2016. Boasting a year-on-year growth in trade of between 9% and 22%, (compared to the regional average of less than 7%) Hungary, Poland and Slovakia were not only Hong Kong’s key trading partners in the CEE, but the city’s fast-growing export destinations in the region last year.

As the vibrant Sino-V4 investment flows are playing an increasingly important and active role in nurturing V4 businesses to take on a more global perspective, more and more V4 enterprises are looking further afield in their search for new markets. This is also partly due to the dire need to compensate for the loss of the Russian market due to the ongoing economic sanctions between the EU and Russia. In this regard, Hong Kong, widely considered a safe and clear-cut gateway for V4 companies to explore the Chinese mainland market, is seeing an encouraging inflow and expansion of well-known V4 enterprises, products and brands.

The unique combination of a vibrant capital market with diverse financing channels and a large professional and financial advisory services cluster with extensive global networks and affiliations has thus made Hong Kong an irreplaceable partner for V4 investors, intermediaries and project owners hoping to take advantage of BRI and “16+1” opportunities. As a regional hub for legal services and dispute resolution underpinned by a trusted common law system and an independent judiciary, Hong Kong can be a crucial link in providing highly sought-after assurances to new-to-the-market V4 enterprises and investors.

New Positions of V4 Nations in Sino-CEE Co-operation

Strengthening Sino-V4 trade and investment flows are certainly good signs of the successful implementation of the 16+1 format and BRI in CEE. They have empowered the V4 countries to reinvent and reposition themselves in the bigger picture of Sino-CEE co-operation, while providing traders and manufacturers with far more possibilities in terms of regional distribution and supply chain management.

Poland: Profiting from Increasing Asia-Europe Rail Traffic

Poland, as the region’s largest economy, has successfully captured the lion’s share of the increasing Eurasian rail traffic and developed itself into a rail logistics hub for Asia-Europe cargo trains, thanks partly to the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian conflicts that have compromised the Eurasian rail traffic passing through Russia and Ukraine to Hungary or Slovakia. This, together with the nation’s unrivalled advantage of being the only one among the V4 countries to have access to open sea, has made Poland a natural choice with respect to regional distribution in CEE.

New projects, such as the Pomeranian Special Economic Zone (PSEZ) in Biala Podlaska near the Polish-Belarusian border, will also further empower the country to better accommodate the increasing demand for railway track gauge change (due to the differences of the Russian broad-gauge system and the European standard gauge system), transshipment and even manufacturing processing facilities.

Riding on the better Asia-Europe rail connection, and the cheaper rail freight due to Asia-bound trains not usually being as fully loaded as Europe-bound trains, Polish companies such as vegetables and fruit growers have started to send apples and other processed food to the Chinese market by rail. This trend has also led to Hong Kong traders and service providers becoming a lifestyle showcase for Polish food and beverages including wine, beer, spirits, fruit and derivatives such as jam, juices and cosmetics.

Hungary: Leading the Way in BRI Co-operation

Hungary is the first European country to sign a memorandum of understanding (MoU) on BRI cooperation with the Chinese mainland. The country’s “Opening to the East” policy is very much in line with the BRI and has been well received by investors such as China’s leading electric automaker BYD, which opened its first fully-owned bus plant in Europe in the northern Hungarian town of Komarom in April this year. Meanwhile, several well-known Hungarian companies, including the world-leading Building Information Modeling (BIM) software developer and a significant player in the field of global female healthcare, have continued to grow their Asian businesses through either their regional headquarters or partners in Hong Kong.

Being the No.1 destination of Chinese outbound FDI in CEE, Hungary is also an important partner to RMB internationalisation in Europe. Home to the regional headquarters of the Bank of China (BOC), which has operated a subsidiary in the country since 2003 and maintained a full-fledged branch since 2014, Hungary was selected by the Bank to launch its first RMB clearing centre in CEE in October 2015 and its first Chinese RMB and Hungarian forint debit card in Europe in January 2017.

As regards logistics, the thrice-weekly direct cargo flights from Hong Kong to Budapest, the capital of Hungary, have made the country a possible air hub for cargo distribution in CEE, while the ongoing project of the high-speed Budapest-Belgrade rail line (which is expected to achieve substantial progress this year) and its further extension to Skopje, the capital of Macedonia, and the Greek capital Athens, will afford the landlocked country a better connection with seaports in the Adriatic and Mediterranean Seas. There is also the already serviceable China-Europe land-sea fast intermodal transport route connecting Hungary with the Greek Port of Piraeus operated by China COSCO Shipping.

The Czech Republic: Boom Time for China-Led M&As

Having one of, if not the best flight passenger connections with the Chinese mainland among CEECs, the Czech Republic welcomes more Chinese tourists (more than 300,000 in 2016) than any other country in the region. The increased belly cargo capacities plus the new cargo flights routing from Hong Kong to Prague have also enabled Chinese express delivery companies to better fulfill the cross-border e-commerce bonanza.

Boosting one of the densest rail networks in Europe (after Luxembourg and Belgium), the Czech Republic has also attracted many multinationals such as Foxconn and Amazon to set up regional logistics centres. As a leading global producer of wheelsets, wheels, axles and other wheelset components for rolling stock, Czech companies are also heavily involved in the expanding Eurasian rail development. One such company, which won the MTRC contract to supply wheels for MTR passenger trains in 2015, opened its first Asia office in Hong Kong in September 2016.

Aside from tourism and logistics, Czech Republic sees a wide array of Chinese-led M&A deals spanning sport, real estate, airlines, travel agencies, hotels, breweries and most recently a DIY and gardening chain. Ongoing deals, including the takeover of the Group Skoda Transportation, the biggest producer of railway vehicles in CEE, by China Railway Rolling Stock Corporation (CRRC), are expected to open the door for Chinese manufacturers to march into the European market, source of technology and pool of talents. Some of the M&A deals have been done through the corporate structures of Chinese enterprises in Hong Kong, while at least one famous Czech glass and lighting company has set up a holding company in Hong Kong to stay close to both the production base in the Chinese mainland and the rosy residential and commercial property market in Asia.

Slovakia: BRI Investment and the Route to Modernisation

Slovakia, with the highest per-capita car production in the world, has been a magnet for auto-related investment in CEECs. All three established car producers – Volkswagen, Peugeot Citroën and Kia – and their tier 1 and tier 2 suppliers are constantly expanding their manufacturing plants in the country, while the investment project Jaguar Land Rover (starting production in 2018) has become the largest business case in Europe during the last seven years.

The recent acquisition of the country’s largest steel mill in Košice by He-Steel Group of China, the world’s second largest steel maker, has not only helped the Chinese steel maker to gain a foothold in the European steelmaking industry to avoid prohibitive EU anti-dumping duties on steel imports, but also highlighted Slovakia’s strategic location to facilitate manufacturing industries such as automotive and electronics that utilise raw materials coming from non-EU European suppliers such as Ukraine.

To prepare for the expected increase in rail cargo traffic between Europe and Asia and strengthen its attractiveness for international manufacturing and logistics companies, Slovakia, riding on its favourable catchment zone in between seaports in southern Europe (e.g., the Slovenian Port of Koper and the Italian Port of Trieste) and northern Europe (e.g., the Port of Hamburg), is active in developing and upgrading its infrastructure. This includes the modern transshipment facilities of Slovakian cities such as Bratislava, the country’s capital, and Košice in eastern Slovakia, close to Ukraine, Hungary and Poland.

Hardware aside, the Slovakian government is keen on adopting and promoting the use of new technology such as electronic locks and electronic customs clearance systems to allow cargo owners and forwarders to facilitate a more effective means to track or trace cross-border cargo movement. Meanwhile, the country is stretching its wings wide to Asia, including, but not confined to, a plan to start a double tax treaty negotiation with Hong Kong soon.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

GDP (US$ Billion)

161.18 (2018)

World Ranking 57/193

GDP Per Capita (US$)

16,484 (2018)

World Ranking 54/192

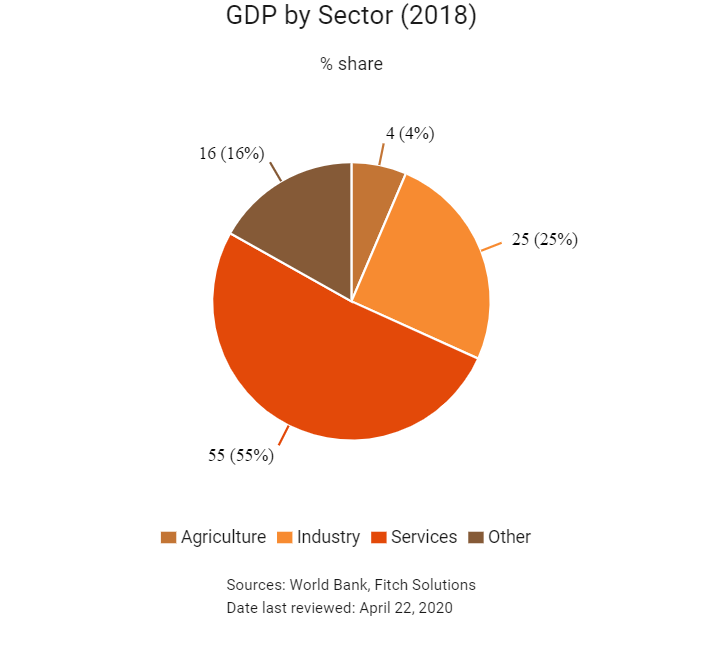

Economic Structure

(in terms of GDP composition, 2019)

External Trade (% of GDP)

163 (2019)

Currency (Period Average)

Hungarian Forint

290.66per US$ (2019)

Political System

Republic

Sources: CIA World Factbook, Encyclopædia Britannica, IMF, Pew Research Center, United Nations, World Bank

Overview

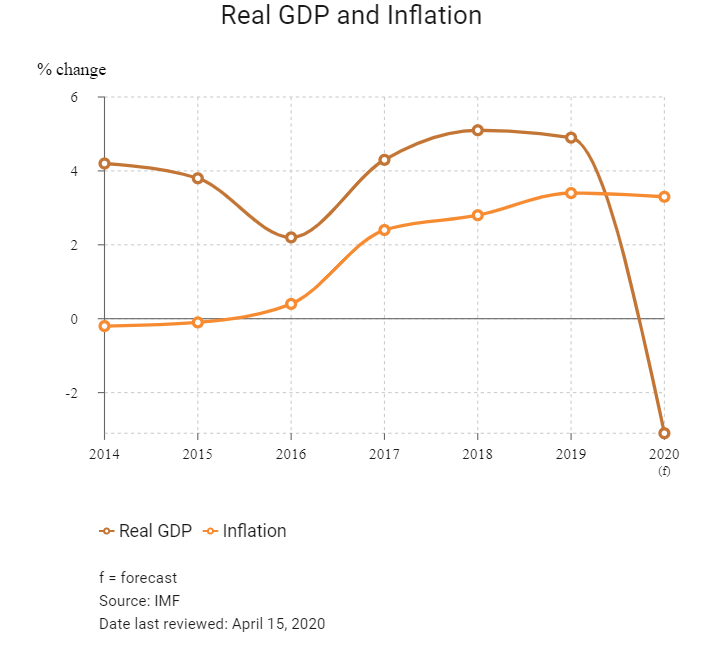

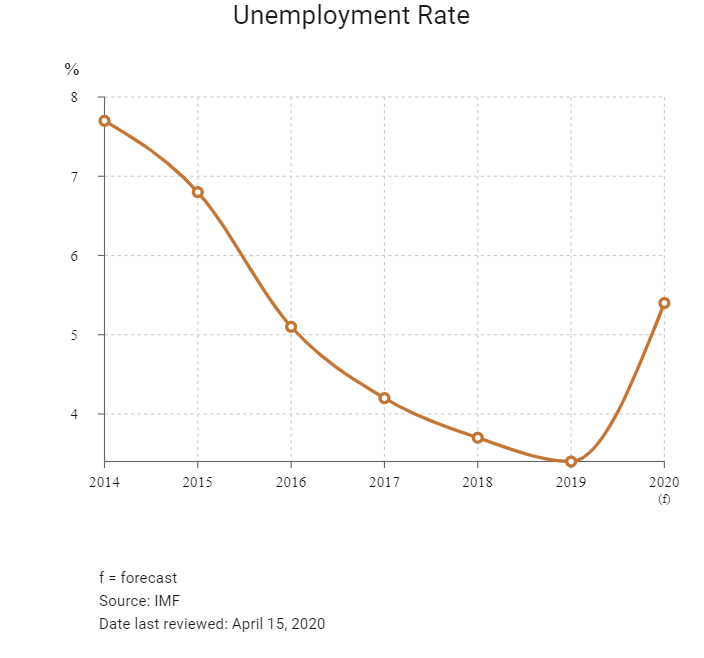

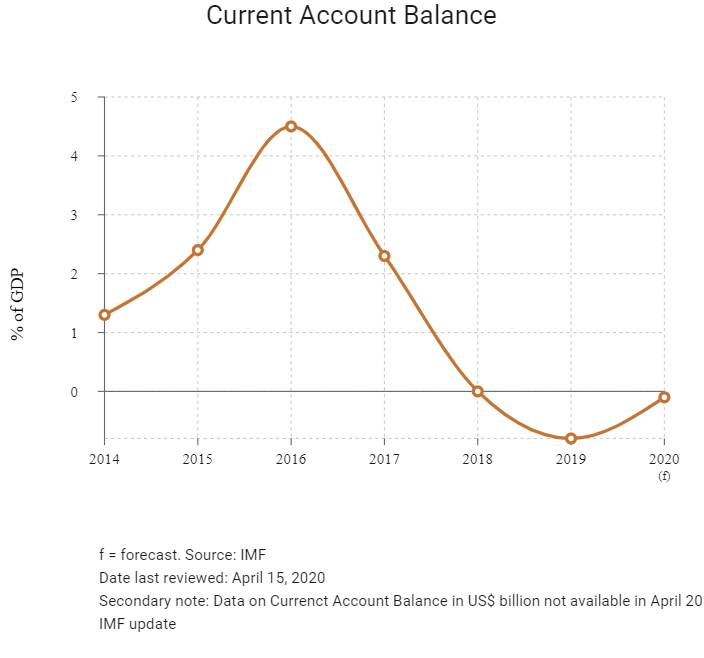

Since transitioning from a centrally planned economy to a market economy, Hungary has made significant economic progress. Investment and private consumption are now among the key drivers of growth, supported by the recovery of credit to the private sector. Economic growth rates in Hungary will ease in the coming years, but remain comfortably higher than in more developed European Union (EU) peers. Emerging from a protracted period of private deleveraging, the economy will be boosted by stronger consumer demand. However, a large public debt load and precarious operational risk backdrop will weigh on Hungary's growth potential relative to some emerging EU peers. Major headwinds facing Hungary's economy are its tight labour market, severe labour shortages and worsening demographic profile, which pose risks to the country's foreign direct investment (FDI) and export-orientated growth model.

Source: Fitch Solutions

Major Economic/Political Events and Upcoming Elections

April 2018

Prime Minister Viktor Orbán was re-elected for a fourth term; his Fidesz party won a supermajority in the national assembly.

September 2018

The European Parliament initiated Article 7 proceedings against Hungary, which could result in EU structural funding cuts in the future.

March 2019

France-based automotive supplier GMD Group announced plans to build a vehicle parts factory in Dorog, northern Hungary, with an investment of HUF14.5billion (USD52 million).

March 2019

Hungary's governing Fidesz party was suspended from the European People's Party.

October 2019

MOL Group laid the foundation stone for a EUR1.2 billion (USD1.3 billion) polyol manufacturing plant in Tiszaújváros, Hungary. The Government of Hungary would contribute EUR131 million (USD143.5 million) via tax allowances and an investment grant towards the project. The facility would be equipped with technology such as the HPPO process (propylene oxide from hydrogen peroxide) developed by thyssenkrupp and Evonik Industries. The plant was expected to become operational in 2021.

March 2020

To mitigate the spread of Covid-19, Hungary declared a state of emergency on March 11. Containment measures include banning of public gatherings and restrictions on travel and economic activity.

On March 19, the government imposed a moratorium on all loan repayments for individuals and companies until the end of 2020.

Hungary passed a new law on March 30, which granted Prime Minister Viktor Orbán the power to rule by decree. Parliament was suspended for the rest of 2020.

April 2020

In response to the coronavirus pandemic, on April 9, Hungary announced an Economy Protection Fund as one of its support packages. The Fund would be financed through primarily through reallocations from ministries’ resources. It aimed to protect jobs, notably by subsidising wages to companies for workers who were put on shortened work hours; created jobs by supporting investments worth a total of HUF450 billion; and supported priority sectors, including tourism, health, food, agriculture, construction, logistics, transport, film and entertainment industries.

April 2022

Parliamentary elections scheduled.

Sources: BBC Country Profile – Timeline, Fitch Solutions

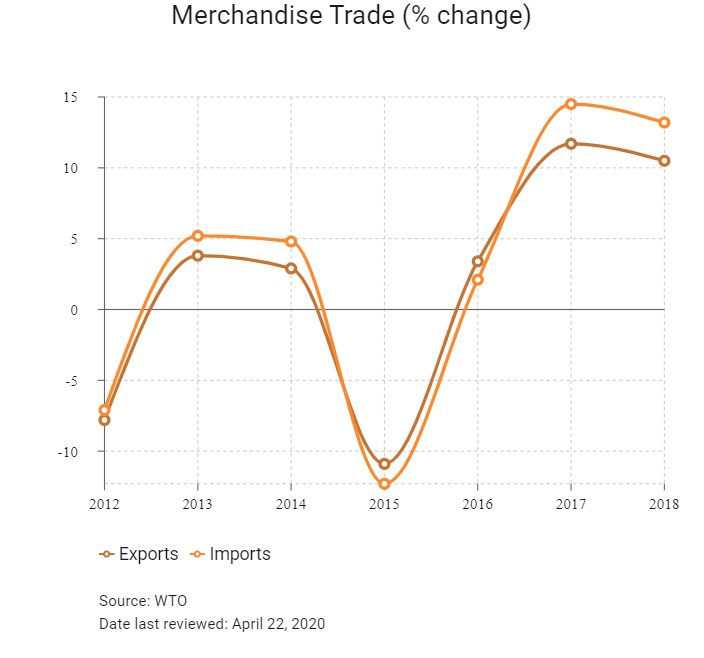

Merchandise Trade

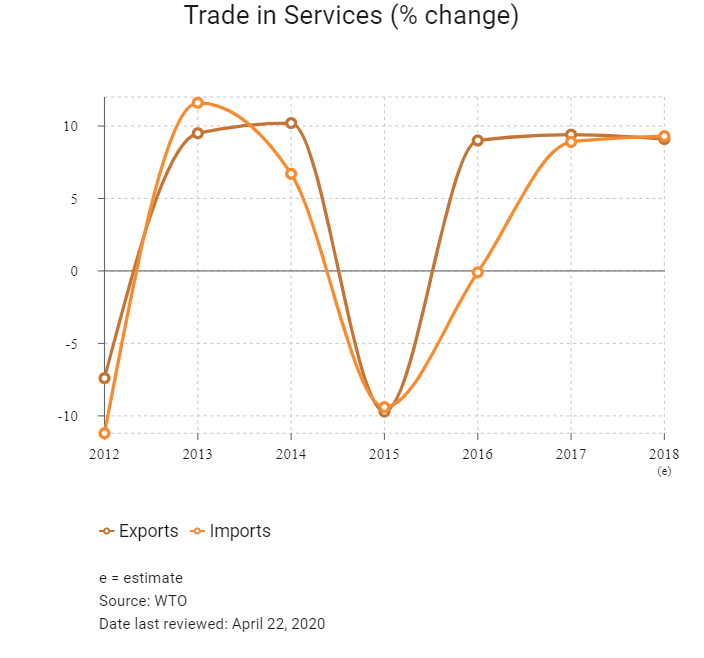

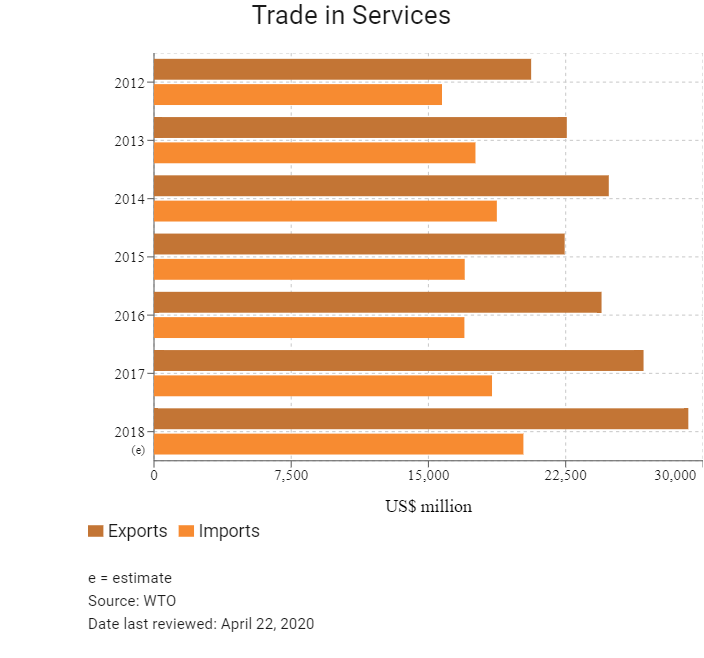

Trade in Services

- Hungary has been a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) since January 1, 1995 and a member state of the EU since May 1, 2004.

- Hungary's main trade partners are in the EU, and the absence of customs charges supports large volumes of trade. All EU member states adopt common external trade policy and measures. The country's trade policy is largely identical to that of the wider regional bloc.

- Hungary applies the EU's Common External Tariff, which means that goods manufactured and imported from within the EU are not subject to customs charges. The EU updated its trade policy (and by extension its import tariffs, customs, duties and procedures) in 2017 and 2018. The average tariff rate for EU states is just 1%, among the lowest globally, although goods imported from outside the EU incur duties of between 0% and 17%. Most of the country's major trade partners are within the EU, and risks are thus less pronounced, such that Hungary's average tariff rate stands at 1.5%. Once goods are cleared by customs authorities upon entry into any EU member state, these imported goods can move freely among EU member states without any additional customs procedures.

- In December 2016, EU states agreed on a proposal to modernise the EU's trade defence instruments with a view to shielding EU producers from damage caused by unfair competition. The proposed regulation amends current anti-dumping and anti-subsidy regulations to better respond to unfair trade practices and furnishes Europe's trade defence instruments with more transparency, quicker procedures and more effective enforcement. In exceptional cases, such as in the presence of distortions in the cost of raw materials, it will enable the EU to impose higher duties through the limited suspension of the lesser duty rule. This will provide some protection to Hungary's secondary and tertiary sectors.

- In 2016, the European Commission (EC) introduced an import licensing regime for steel products exceeding 2.5 tonnes. The regulation will be active until May 15, 2020. In Q215, the EC issued regulations on trade restrictions with Turkey on cattle, beef, watermelons and prepared tomatoes. This will help protect domestic agriculture and regional farming businesses.

- In June 2018, the EU imposed import duties on 182 goods from the United States in reaction to the steel and aluminium import duties imposed by Washington on the EU. Daimler AG and BMW have stated that they will be putting their Hungarian investments on hold in response to lower demand and fears of a disproportionately large impact on the autos industry resulting from auto tariffs from the United States.

- The EU is party to about 50 free trade agreements (FTAs) and, consequently, access to other markets of the countries concerned is currently mediated through those agreements. The EU's Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP) came into effect on January 1, 2014. Under the scheme, tariff preferences have been removed for imports into the EU from countries where per capita income has exceeded USD4,000 for four years in a row. Regarding Hong Kong, the territory has been fully excluded from the EU's GSP scheme since May 1, 1998.

- A number of products orginatingfrom Mainland China are subject to the EU's anti-dumping duties, including bicycles, bicycle parts, ceramic tiles, ceramic tableware and kitchenware, fasteners, ironing boards and solar glass. As of December 2017, the EU did not apply any anti-dumping measures on imports originating from Hong Kong.

- In December 2019, the EU issued a regulation imposing additional import tariffs on a number of fruits and vegetables for the period 2020 to 2021.

Sources: WTO – Trade Policy Review, Global Trade Alert, Fitch Solutions

Trade Updates

- As a member of the EU, Hungary is part of the same trade agreements as its 27 peer states. The region negotiates and enters into trade agreements as a collective owing to the single market nature of the union. In total, the EU has approximately 70 preferential trade agreements in place.

- Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán met with Mainland China’s President Xi Jingping in April 2019 in Beijing in order to promote the development of relations and cooperation between Mainland China and the countries of the Central and Eastern European region. Orbán was in Mainland China in order to attend the second international forum on the Belt and Road Initiative, from which Hungary is set to benefit, in addition to conducting bilateral talks with Mainland China.

Multinational Trade Agreements

Active

- Hungary has been a member of the EU since May 1, 2004, adopting the EU's common external trade policy and measures. The EU is a political and economic union of 27 member states that are primarily located in Europe. Within the Schengen Area, passport controls have been abolished. A monetary union was established in 1999; it is composed of 19 EU member states that use the euro currency. However, Hungary maintains its own currency – the forint.

- EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA): This has provisionally been applied since September 21, 2017, having been signed in October 2016. CETA is expected to strengthen trade ties between the two regions. The agreement is expected to boost trade between partners by more than 20%. Hungary expects CETA to improve trade in goods and services between the two countries while also boosting FDI. According to Hungarian authorities, USD11 billion in FDI has already arrived in Hungary from Canada, highlighting the importance of further market and trade liberalisation. CETA also opens up government procurement. Canadian companies will be able to bid on opportunities at all levels of the EU government procurement market and vice versa. CETA means that Canadian provinces, territories and municipalities are opening their procurement to foreign entities for the first time, albeit with some limitations regarding energy utilities and public transport.

- Europe Free Trade Association (EFTA): the EFTA includes Switzerland, Norway, Liechtenstein and Iceland. The European Economic Area (EEA) unites the EU member states and the three EEA EFTA states into an internal market governed by the same basic rules. These rules aim to enable goods, services, capital and persons to move freely about the EEA in an open and competitive environment, a concept referred to as the four freedoms.

- EU-Turkey: The EU and Turkey are linked by a customs union agreement which came into force on December 31, 1995. Turkey has been a candidate country to join the EU since 1999 and is a member of the Euro-Mediterranean partnership. The customs union with the EU provides tariff-free access to the European market for Turkey, benefitting both exporters and importers. Turkey is the EU's fourth largest export market and fifth largest provider of imports. The EU is Turkey's largest import and export partner. Turkey's exports to the EU are mostly machinery and transport equipment, followed by manufactured goods. At present, the customs union agreement covers all industrial goods but does not address agriculture (except processed agricultural products), services or public procurement. Bilateral trade concessions apply to agricultural as well as coal and steel products. In December 2016, the EC proposed the modernisation of the customs union and the extension of the bilateral trade relations to areas such as services, public procurement and sustainable development.

- EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA): In July 2018, the EU and Japan signed a trade deal that promises to eliminate 99% of tariffs that cost businesses in the EU and Japan nearly EUR1 billion annually. According to the EC, the EU-Japan EPA will create a trade zone covering 600 million people and nearly a third of global GDP. The result of four years of negotiation, the EPA was finalised in late 2017 and came into force on February 1, 2019, after the European Parliament ratified the agreement in December 2018. The total trade volume of goods and services between the EU and Japan is an estimated EUR86 billion. The key parts of the agreement will cut duties on a wide range of agricultural products and seeks to open up services markets, particularly financial services, e-commerce, telecommunications and transport. Japan is the EU's second biggest trading partner in Asia after Mainland China. EU exports to Japan are dominated by motor vehicles, machinery, pharmaceuticals, optical and medical instruments, and electrical machinery.

- EU-Southern African Development Community (SADC) EPA (Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Mozambique, Namibia and South Africa): An agreement between EU and SADC delegations was reached in 2016 and is fully operational for SADC members following the ratification of the agreement by Mozambique. The remaining six members of SADC included in the deal (the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Zambia and Zimbabwe) are seeking EPAs with the EU as part of other trading blocs – such as with East or Central African communities.

Signed, Awaiting Ratification

- EU-Central America Association Agreement (Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Belize and the Dominican Republic): An agreement between the parties was reached in 2012 and is awaiting ratification (30 of the 34 parties have ratified the agreement as of October 2019). The agreement has been provisionally applied since 2013.

- EU-Vietnam FTA: In July 2018, the EU and Vietnam agreed on final texts for the EU-Vietnam FTA and the EU-Vietnam Investment Protection Agreement. As of October 2019, the final text of the agreement has been finalised and is awaiting signature and conclusion. On March 30 2020, the EU Council concluded the FTA between the EU and Vietnam. Once the Vietnamese National Assembly also ratifies the FTA, the agreement will enter into force before end 2020.

- EU-Mercosur: The EU and Mercosur (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay) signed a trade deal on June 28, 2019, after 20 years of negotiations. The trade agreement for goods and services will cover nearly 25% of global GDP and almost 800 million people. The deal is expected to cut duties on EU exports to Mercosur by EUR4 billion annually and eliminate tariffs on 93% of Mercosur's exports to the EU and 91% of EU exports to Mercosur states. The deal will also include access to public procurement contracts. Mercosur states will greatly benefit from increased access to the EU for agricultural goods, which has resulted in opposition to the deal by European farmers. European firms, especially those in the manufacturing and industrial sector, will have an advantage over other competitors after the removal of high tariffs. Along with other Central and Eastern European countries, Hungary is likely to benefit substantially from the deal as high valued-added automotive and other mechanical parts are a significant export to South America.

Under Negotiation

- EU-Australia: The EU, Australia's second largest trade partner, has launched negotiations for a comprehensive trade agreement with Australia. Bilateral trade in goods between the two partners has risen steadily in recent years, reaching almost EUR48 billion in 2017 with bilateral trade in services adding an additional EUR27 billion. The negotiations aim to remove trade barriers, streamline standards and put European companies exporting to or doing business in Australia on equal footing with those from countries that have signed up to the Trans-Pacific Partnership or other trade agreements with Australia. The Council of the EU authorised opening negotiations for a trade agreement between the EU and Australia on May 22, 2018. Negotiations were still underway as at March 2020.

- EU-United States (Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership): This agreement was expected to increase trade and services, but it is unlikely to pass under United States President Donald Trump's administration against a backdrop of rising global trade tensions.

Sources: WTO Regional Trade Agreements database, European Commission, Fitch Solutions

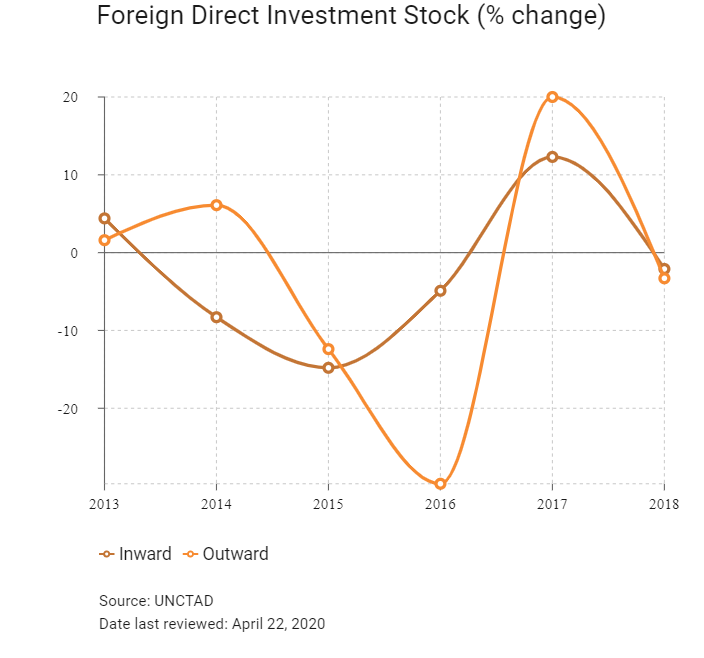

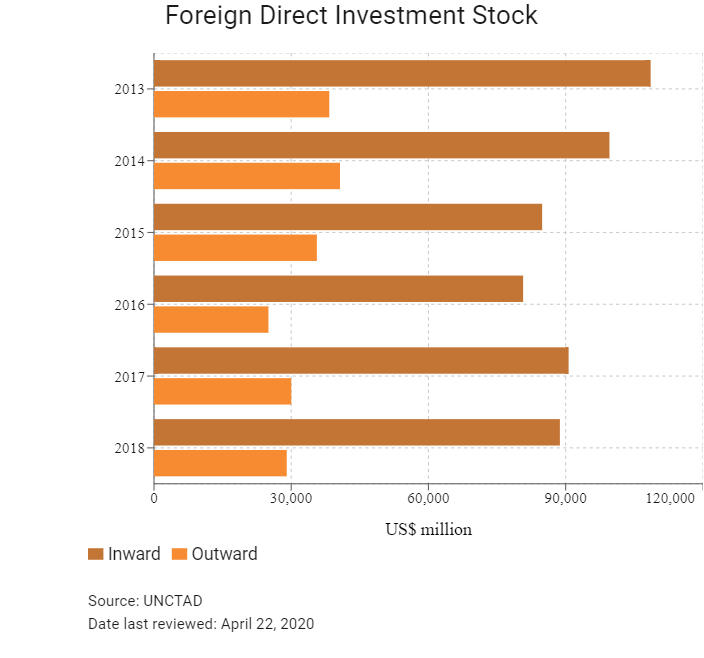

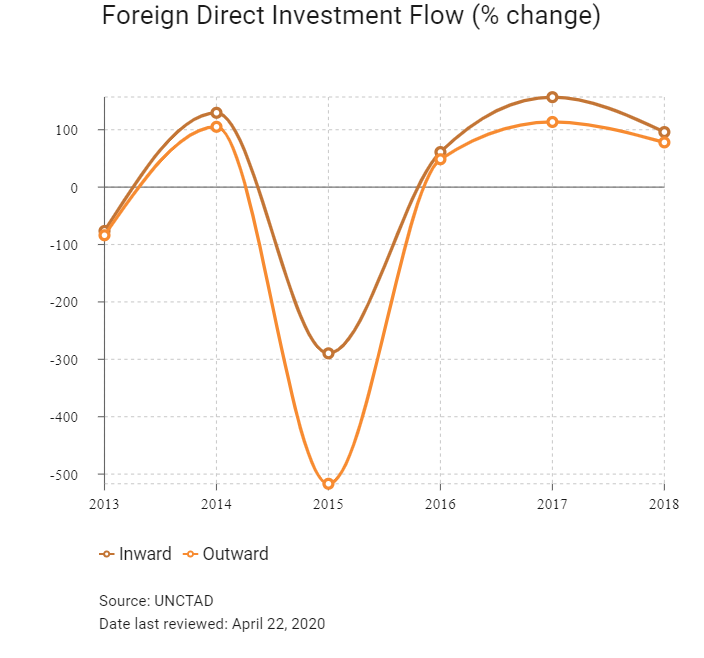

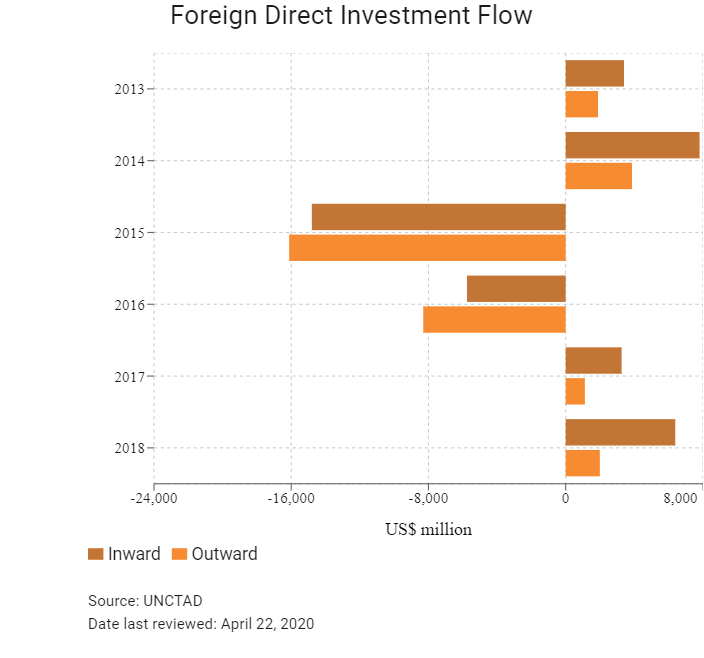

Foreign Direct Investment

Foreign Direct Investment Policy

- The Hungarian Investment Promotion Agency (HIPA) offers management consultancy services to address the needs of investors and is governed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. HIPA also acts as a mediator between business and government, preparing policy proposals to improve the business environment.

- Hungary's accession to the EU was accompanied by the tightening of legal protection for foreign investment, and the government has attempted to guide capital inflows towards targeted sectors such as manufacturing facilities, research and development, IT, automobiles, and tourism. The property rights of foreign investors are also guaranteed against expropriation or nationalisation, except in cases of national security, in which the private owner is entitled to fair compensation.

- The EU formally adopted region-wide legislation on the screening of FDI in February 2019, with new guidelines issued in March 2020 and implementation expected to continue until end 2020. The new legislation will allow member states to screen FDI regarding critical infrastructure, both physical and virtual; sensitive facilities and investments in land and real estate; critical technologies, such as artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, quantum technology, nuclear technology and biotechnology; critical inputs, such as food or fuel; media which threaten pluralism or the freedom thereof; and any services or products which may compromise data security. Hungary previously had no such rules, but the implementation of such oversight will bring it in line with the practices of a number of EU peers.

- There are no legal restrictions on foreign ownership in any sector, and under the Foreign Investment Act of 1988, international companies are guaranteed equal treatment alongside Hungarian businesses, with full freedom regarding the repatriation of profits.

- The manufacturing sector, particularly automobiles, as well as the IT and biological science sectors, have traditionally been the major recipients of FDI owing to their high value-added and export-led focus. The Hungarian government encourages investments in both export-oriented manufacturing and high value-added sectors, such as research and development, and service centres. There are also considerable opportunities that exist in biotechnology, information and communications technology, software development, the automotive and defence industries, and tourism.

- Currently, foreign firms control 66% of the manufacturing sector, 90% of the telecommunications sector and 35% of the energy sector. The private sector currently produces about 80% of Hungary's economic output. Foreign investors interested in financial institutions and insurance companies must officially notify the government of their intentions, but do not need authorisation in advance.

- Under the Investment Act, companies incorporated in Hungary are permitted to purchase and own real estate to support their economic activities. Nevertheless, only private Hungarian or EU citizens resident in Hungary with a minimum of three years of experience working in agriculture or holding a degree in an agricultural discipline can purchase farmland, according to the 2014 Land Law. All others may only lease farmland.

- The Hungarian government regulates the prices of certain goods, setting upper and lower limits to which the private sector must adhere. Price-regulated sectors include energy and pharmaceuticals, and companies operating in these fields have suffered losses in cases where the government has been too slow to adjust upper limits or has failed to meet subsidy obligations, as in the case of medicinal goods and electricity.

- The Hungarian government has publicly declared that reducing foreign bank market share in the Hungarian financial sector and tightening regulations governing non-government organisations are key priority areas. Accordingly, several state-led initiatives over the past several years have targeted the banking sector and reduced foreign participation.

- Regulations in 2015 obligated banks to retroactively compensate borrowers for interest rate increases on certain consumer loans. Increasing entry barriers in certain sectors could have undermined previous sunk-cost investments, contributing to a general sense of policy-induced uncertainty regarding the protection of intangible assets.

- Performance requirements, such as job creation or investment minimums, can be imposed as a condition for establishing, maintaining or expanding an investment. Hungary's rules and regulations regarding labour mobility are broadly in line with EU directives. Most non-EU citizens require a work visa and permit in order to enter and work in Hungary, which generally takes about a month to obtain. There is a large amount of bureaucracy that businesses must contend with when trying to bring in foreign workers from non-EU states.

- As part of the country's EU accession, Hungary eliminated foreign trade zones. Although the Ministry of National Economy had plans to nominate customs-free zones, there currently seems to be little demand. Nevertheless, Hungary offers a well-developed incentive system for investors, which is anchored by a special incentive package for investments over a certain value-typically more than USD11 million. Administered by HIPA and managed by the Ministry of National Development, the incentive system is compliant with EU regulations on competition and state aid.

- In 2013 the government established free entrepreneurial zones in remote and underdeveloped regions of the country, which aim to promote economic growth and job creation. Businesses located in these zones will benefit from a lower qualification threshold and fewer stipulations for a range of tax incentives. Free entrepreneurial zones are open to all types of businesses, although the government will be more inclined to provide generous incentives for targeted industries, including manufacturing and research and development. Additional government aid incentives are available at varying rates depending on the location of investment.

- International investors benefit from bilateral investment agreements with more than 50 partners, including Mainland China, Germany, Russia and the United Kingdom. There is no investment agreement with the United States, but Hungary has a double taxation treaty with Washington and 50 other governments, which eliminates the risk of double taxation. Hungary has also signed almost 50 strategic cooperation agreements with international companies, including Coca-Cola, General Electric and Hewlett-Packard, which aim to consolidate the investment of foreign companies in Hungary and improve cooperation between investors and the government.

Sources: WTO – Trade Policy Review, the International Trade Administration, United States Department of Commerce, Hungarian Investment Promotion Agency

Free Trade Zones And Investment Incentives

|

Free Trade Zone/Incentive Programme |

Main Incentives Available |

|

The free entrepreneurship zone contains more than 900 settlements in underprivileged areas of Hungary designated by the government and coordinated by the regional business development agency that consists of individual regions separated by public administration, borders and topographical lot numbers and which are treated jointly for regional development purposes. |

Investors who establish one of the following centres or facilities stand to benefit from incentive packages: |

Sources: Hungarian Government websites, Fitch Solutions

- Value Added Tax: 27%

- Corporate Income Tax: 9%

Sources: Hungary National Tax and Customs Administration

Important Updates to Taxation Information

- The government aims to further decrease the labour tax rate (especially the social contribution tax rate) over the period 2020 to 2022. The proposed reduced social tax rate is 15.5% for FY2020 down from 19.5% (if certain conditions are met) and further reductions are expected (the final proposed rate is 11.5%) by FY2022, subject to certain conditions.

- On December 12 2019, the Hungarian National Tax and Customs Administration issued a guide of value added tax (VAT) changes for 2020. The changes include: 1) a rate reduction for accommodation services to 5% from 18%, subject to a 4% tourism development contribution; 2) the harmonisation of intra-EU deliveries of goods; 3) the determination of the place of performance in a chain transaction; 4) rules for tax-free intra-EU sales; and 5) the allowance of VAT base reductions for bad debt claims. These changes took effect January 1, 2020.

Business Taxes

|

Type of Tax |

Tax Rate and Base |

|

Corporate Income Tax |

9% |

|

Dividends |

5% on net earnings (except distribution by companies in the oil and gas sector). |

|

Capital Gains Tax |

9% |

|

Mines, energy producers and energy distribution system operators are subject to energy suppliers’ income tax |

31% |

|

Local Business Tax |

2% on turnover or gross margin |

|

Social security contributions |

- 19.5% on gross salaries paid by employer. |

|

Innovation contribution |

0.3% |

|

VAT |

- 27% on sale of goods, services and imports |

Source: Hungary National Tax and Customs Administration

Date last reviewed: April 22, 2020

Localisation Requirements

Hungary's rules and regulations regarding labour mobility are broadly in line with EU directives. Most non-EU citizens require a work visa and permit in order to go and work in Hungary, which generally takes about a month to obtain.

Obtaining Foreign worker permits for skilled workers

There are certain requirements that businesses must meet when trying to bring in foreign workers from non-EU states. First, a workforce demand is required. The hiring company must advertise the job at the Hungarian Labour Office for a fixed period (around 15 days). This is to give unemployed Hungarian citizens a chance to apply for the position. Thereafter, a work permit may be processed. Most work permits and working visas are issued for two years. Both these documents can be renewed to extend the stay in Hungary if the employee continues to fulfil the application requirements. Generally, the highest number of foreign workers employed with a work permit at the same time in the territory of Hungary cannot exceed the number of announced applications in an average month in the year before the year in question. The quota is set at 57,000 work permits in 2019.

Blue Card

The Blue Card is intended for the stay of a highly qualified employee. A foreigner holding a Blue Card may reside in Hungary and work in the job for which the Blue Card was issued or change that job under the conditions defined. High qualification means a duly completed university education or higher professional education which lasted for at least three years. The Blue Card is issued with a term of validity three months longer than the term for which the employment contract has been concluded; however, this is for a maximum period of two years. The Blue Card can be extended. One of the conditions for issuing the Blue Card is a wage criterion – the employment contract must contain gross monthly or yearly wage at least 1.5 times the gross average annual wage.

Visa/Travel Restrictions

Nationals of Canada, Australia and the United States intending to stay in Hungary for more than 90 days need to apply for a long-term stay visa, whereas EU nationals staying for longer than 90 days need only register with the immigration department. In addition, citizens of many other countries may travel to Hungary without a visa and stay for a maximum period of 90 days. For Hong Kong, this exemption applies only to Hong Kong passport holders.

Schengen Visa

Hungary has been part of the Schengen Agreement as of since December 7, 2017, which has made traveling between member countries much easier and less bureaucratic. The Schengen visa and entry regulations are only applicable for a stay not exceeding 90 days. In the wake of the migrant crisis in Europe, the Schengen states have tightened controls at their common external borders to ensure the security of those living or travelling in the Schengen Area.

Sources: Hungarian Government websites, Fitch Solutions

Sovereign Credit Ratings

|

Rating (Outlook) |

Rating Date |

|

|

Moody's |

Baa3 (Stable) |

23/11/2018 |

|

Standard & Poor's |

BBB (Stable) |

28/04/2020 |

|

Fitch Ratings |

BBB (Stable) |

14/02/2020 |

Sources: Moody's, Standard & Poor's, Fitch Ratings

Competitiveness and Efficiency Indicators

|

World Ranking |

|||

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

|

Ease of Doing Business Index |

48/190 |

53/190 |

52/190 |

|

Ease of Paying Taxes Index |

93/190 |

86/190 |

56/190 |

|

Logistics Performance Index |

31/160 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Corruption Perception Index |

64/180 |

70/180 |

N/A |

|

IMD World Competitiveness |

47/63 |

47/63 |

N/A |

Sources: World Bank, IMD, Transparency International

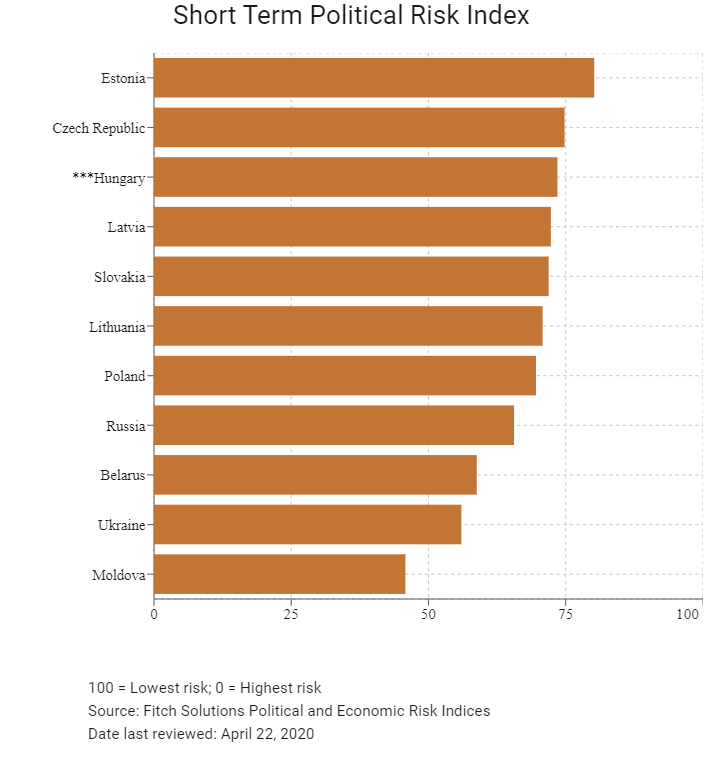

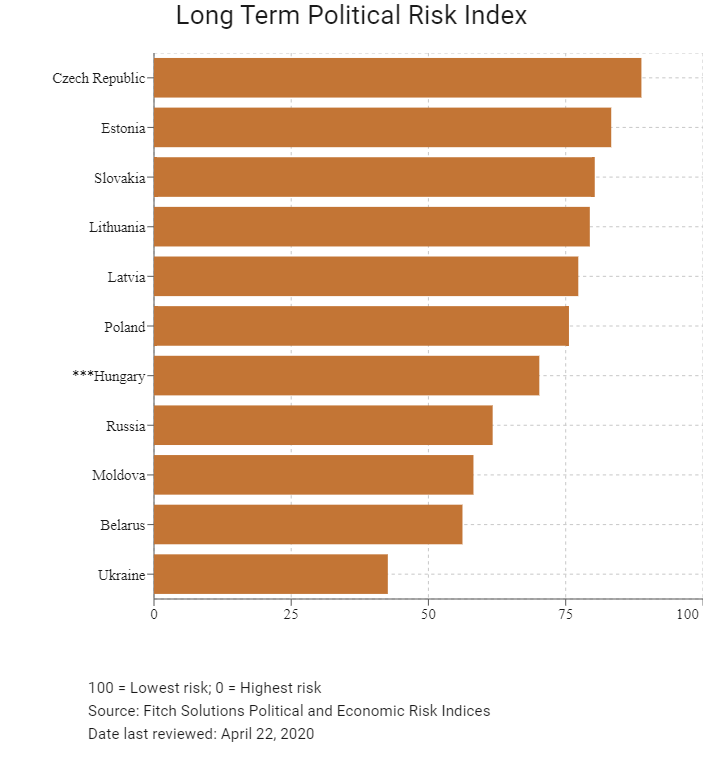

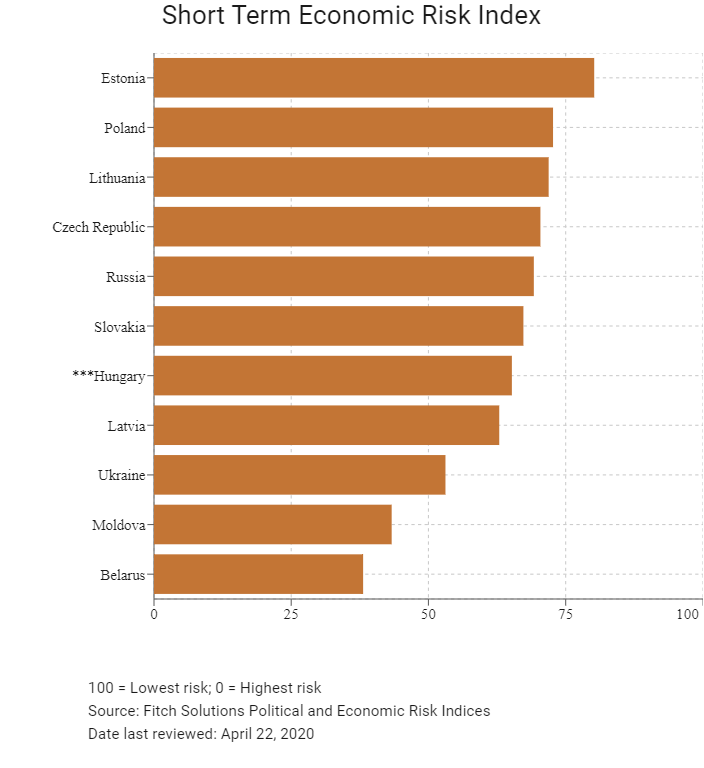

Fitch Solutions Risk Indices

|

World Ranking |

|||

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

|

Economic Risk Index |

36/202 |

34/201 |

33/201 |

|

Short-Term Economic Risk Score |

71.5 |

67.7 |

65.2 |

|

Long-Term Economic Risk Score |

69.8 |

70.1 |

71.0 |

|

Political Risk Index |

69/202 |

71/201 |

68/201 |

|

Short-Term Political Risk Score |

73.5 |

73.5 |

73.5 |

|

Long-Term Political Risk Score |

70.2 |

70.2 |

70.2 |

|

Operational Risk Index |

39/201 |

46/201 |

46/201 |

|

Operational Risk Score |

64.3 |

63.5 |

63.6 |

Source: Fitch Solutions

Date last reviewed: April 22, 2020

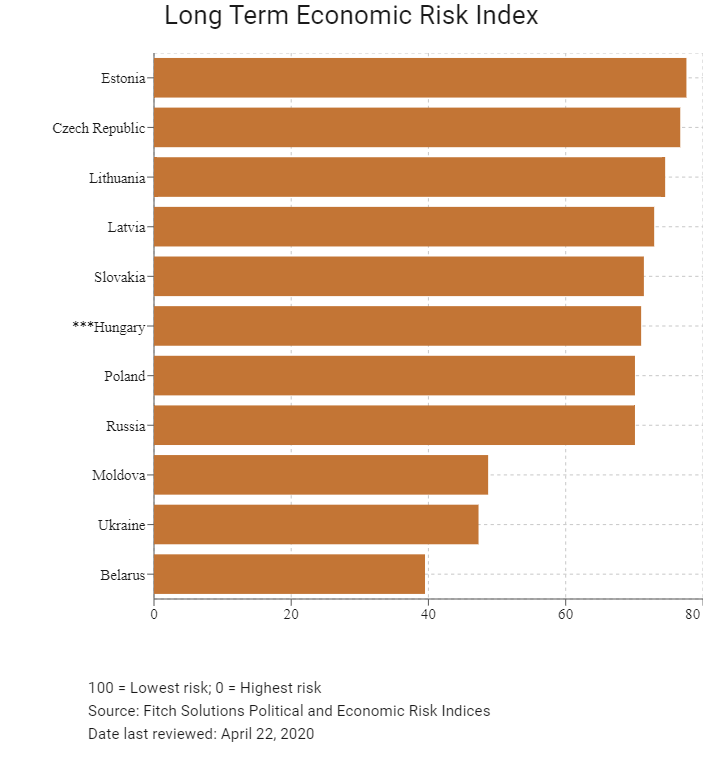

Fitch Solutions Risk Summary

ECONOMIC RISK

Economic growth rates in Hungary will slow in the coming years. An increasingly tight labour market and weakening external demand backdrop due to Covid-19 will weigh on output. Gross external debt will remain somewhat high by regional standards, although the downward trajectory and high proportion of intercompany loans will ensure it is sustainable in the medium term.

OPERATIONAL RISK

Investors in Hungary benefit from the country's relatively stable operating environment and a highly urbanised labour force with a strong skills base. As a member of the EU, Hungary offers open markets and an increasingly competitive corporate tax regime, while its geographic location and strong overland transport links consolidate its position as a major regional trade hub within Central and Eastern Europe. Despite an above-average score, Hungary ranks less competitively against its regional peers as investors face mounting risks associated with high utility costs, compounded by energy import reliance and labour shortages in key sectors, which dent competitiveness in manufacturing industries. Policy uncertainty poses downside risks to the operating environment.

Source: Fitch Solutions

Date last reviewed: April 28, 2020

Fitch Solutions Political and Economic Risk Indices

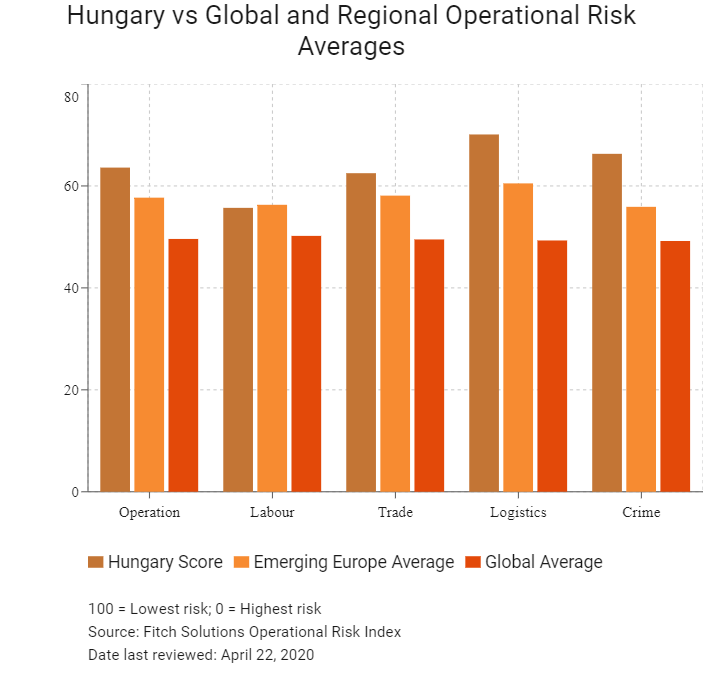

Fitch Solutions Operational Risk Index

|

Operational Risk |

Labour Market Risk |

Trade and Investment Risk |

Logistics Risk |

Crime and Security Risk |

|

|

Hungary Score |

63.6 |

55.7 |

62.5 |

70.1 |

66.3 |

|

Central and Eastern Europe Average |

62.5 |

58.6 |

62.8 |

67.5 |

61.2 |

|

Central and Eastern Europe Position (out of 11) |

7 |

9 |

7 |

5 |

7 |

|

Emerging Europe Average |

57.7 |

56.3 |

58.1 |

60.5 |

55.9 |

|

Emerging Europe Position (out of 31) |

9 |

19 |

12 |

7 |

10 |

|

Global Average |

49.6 |

50.2 |

49.5 |

49.3 |

49.2 |

|

Global Position (out of 201) |

46 |

62 |

53 |

36 |

46 |

100 = Lowest risk; 0 = Highest risk

Source: Fitch Solutions Operational Risk Index

|

Country/Region |

Operational Risk Index |

Labour Market Risk Index |

Trade and Investment Risk Index |

Logistics Risk Index |

Crime and Security Risk Index |

|

Estonia |

70.9 |

63.1 |

75.0 |

71.0 |

74.3 |

|

Czech Republic |

69.4 |

60.6 |

67.0 |

73.6 |

76.5 |

|

Lithuania |

69.4 |

61.3 |

71.1 |

74.3 |

71.0 |

|

Poland |

68.1 |

59.2 |

64.9 |

75.5 |

72.8 |

|

Latvia |

67.1 |

63.5 |

68.2 |

69.4 |

67.4 |

|

Slovakia |

63.7 |

52.1 |

66.2 |

66.8 |

69.6 |

|

Hungary |

63.6 |

55.7 |

62.5 |

70.1 |

66.3 |

|

Belarus |

59.2 |

60.1 |

58.7 |

66.6 |

51.3 |

|

Russia |

58.0 |

65.9 |

57.4 |

67.9 |

40.6 |

|

Moldova |

49.7 |

44.8 |

51.4 |

53.4 |

49.3 |

|

Ukraine |

48.6 |

57.9 |

48.4 |

54.4 |

33.6 |

|

Regional Averages |

62.5 |

58.6 |

62.8 |

67.5 |

61.2 |

|

Emerging Markets Averages |

46.9 |

48.5 |

47.2 |

45.8 |

46.0 |

|

Global Markets Averages |

49.6 |

50.2 |

49.5 |

49.3 |

49.2 |

100 = Lowest risk; 0 = Highest risk

Source: Fitch Solutions Operational Risk Index

Date last reviewed: April 22, 2020

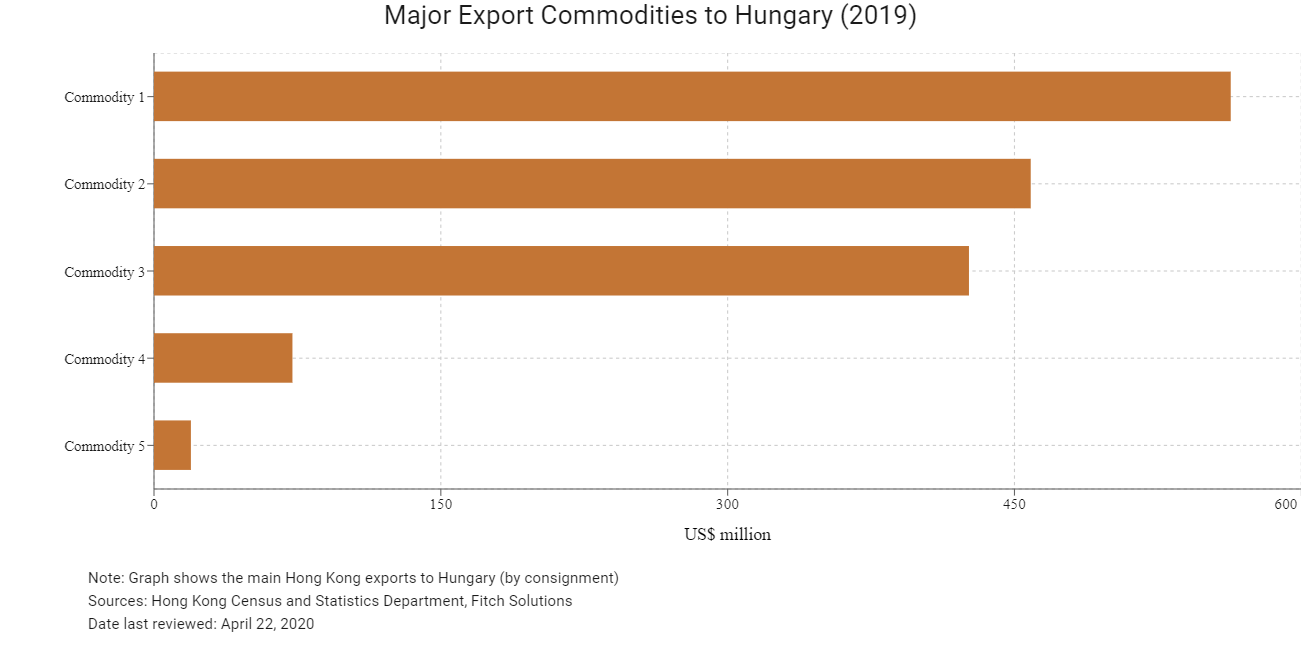

Hong Kong’s Trade with Hungary

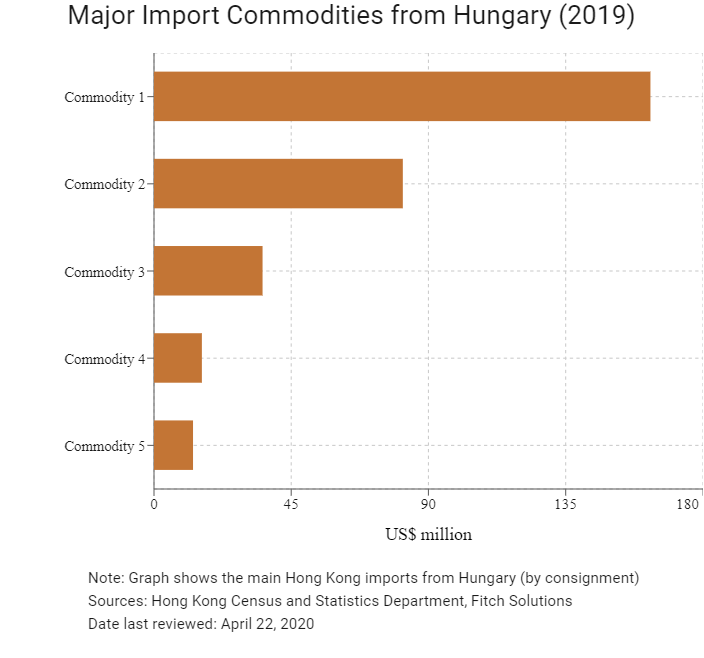

| Export Commodity | Commodity Detail | Value (US$ million) |

| Commodity 1 | Telecommunications and sound recording and reproducing apparatus and equipment | 563.1 |

| Commodity 2 | Office machines and automatic data processing machines | 458.5 |