Chinese Mainland

State Council Reveals List of Key Border Regions for BRI Development

The State Council has issued a list of border zones, ports and cities to be accorded special economic privileges in recognition of the major roles they are expected to play in the development of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

I. Key Experimental Zones for Development and Opening-Up (5)

Dongxing (Guangxi), Mohan (Mengla, Yunnan), Ruili (Yunnan), Erenhot (Inner Mongolia), Manzhouli (Inner Mongolia).

II. National-Level Border Ports (72)

Railway ports (11): Pingxiang (Guangxi); Hekou (Yunnan); Korgas, Alashankou (Xinjiang); Erenhot, Manzhouli (Inner Mongolia); Suifenhe (Heilongjiang); Hunchun, Tumen, Ji'an (Jilin); Dandong (Liaoning).

Road ports (61): Dongxing, Aidian, Friendship Gate, Shuikou, Longbang, Pingmeng (Guangxi); Tianbao, Dulong, Hekou, Jingshuihe, Mengkang, Mohan, Daluo, Mengding, Wanding, Ruili, Tengchong (Yunnan); Zhangmu, Jilong, Pulan (Tibet); Khunjerab Pass, Kalasu, Erkeshtam, Torugart, Muzart, Dulata, Korgas, Baketu, Jeminay, Ahitubiek, Hongshanzui, Takeshiken, Ulastai, Laoyemiao (Xinjiang); Mazongshan (Gansu); Ceke, Ganqimaodu, Mandula, Erenhot, Zhuengadabuqi, Aershan, Ebuduge, Arihashate, Manzhouli, Heishantou, Shiwei (Inner Mongolia); Hulin, Mishan, Suifenhe, Dongning (Heilongjiang); Hunchun, Quanhe, Shatuozi, Kaishantun, Sanhe, Nanping, Guchengli, Changbai, Linjiang, Ji'an (Jilin); Dandong (Liaoning).

III. Border Cities (28)

Dongxing, Pingxiang (Guangxi); Jinghong, Mangshi, Ruili (Yunnan); Artux, Yining, Bole, Tacheng, Altay, Hami (Xinjiang); Erenhot, Aershan, Manzhouli, Ergun (Inner Mongolia); Heihe, Tongjiang, Hulin, Mishan, Mulin, Suifenhe (Heilongjiang); Hunchun, Tumen, Longjing, Helong, Linjiang, Ji'an (Jilin); Dandong (Liaoning).

IV. Border Economic Co-operation Zones (17)

Dongxing, Pingxiang (Guangxi); Hekou, Lincang, Wanding, Ruili (Yunnan); Yining, Bole, Tacheng, Jeminay (Xinjiang); Erenhot, Manzhouli (Inner Mongolia); Heihe, Suifenhe (Heilongjiang); Hunchun, Helong (Jilin); Dandong (Liaoning).

V. Cross-Border Economic Co-operation Zone (1)

China-Kazakhstan-Korgas International Border Cooperation Centre

Crystal Ho and Edison Lian, Guangzhou Office

For further information see: "Enhanced Border Trade and New BRI Privileges Set to Boost Guangxi", 26 February 2016.

| Content provided by |

|

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Xinjiang: A Core Component of Belt and Road

The Belt and Road Initiative is China's development strategy for promoting coordination of economic policies, efficient allocation of resources and deep integration of markets among all countries involved. Besides the 60-plus countries along the Belt and Road routes, many Chinese provinces and cities are also actively involved in supporting this initiative. The Vision and Actions on Jointly Building the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road (hereafter referred to as Vision and Actions) published by the National Development and Reform Commission in March 2015 also points out that, in advancing the initiative, China will fully leverage the advantages of its various regions. That includes making “good use of Xinjiang's geographical advantages and its role as an important window of westward opening up, making it a key transportation, trade, logistics, culture, science and education centre and a core area on the Silk Road Economic Belt".

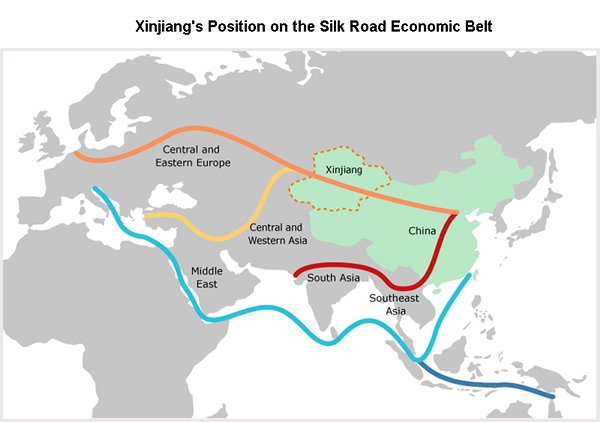

Xinjiang's Crucial Geographical Position

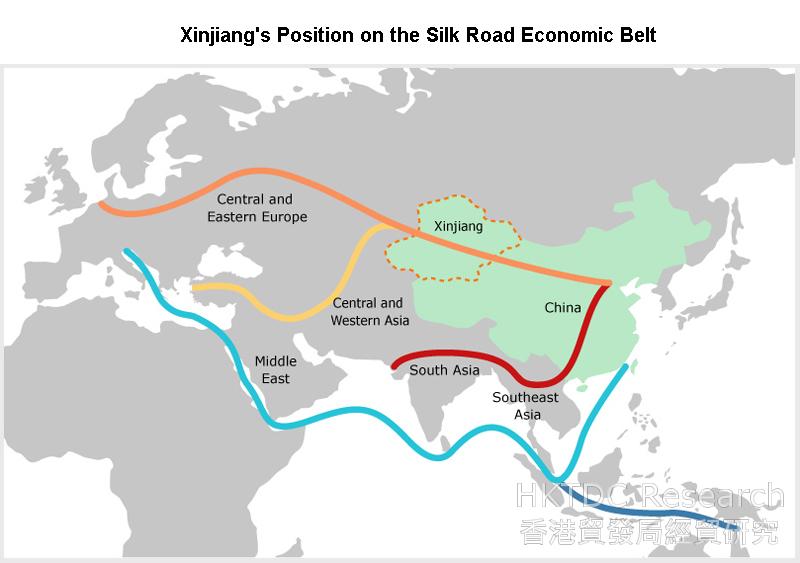

The Silk Road Economic Belt described in Vision and Actions mainly focuses on ways of bringing together China, Central Asia, Russia and the Baltic region of Europe – or, to frame it differently, of linking China with the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean Sea through Central Asia and West Asia. Either description indicates the importance of Central Asia in the development of the Silk Road Economic Belt, with Xinjiang occupying a crucial geographical position as a land transport link to Central Asia.

Xinjiang is bounded by a number of countries, including Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Mongolia. With its total land frontiers extending 5,600 km in length, its boundaries with neighbouring countries are the longest of any Chinese province. In geographical and transport terms, Xinjiang offers a corridor to many countries along the Belt and Road. It has direct connectivity with neighbouring countries and is the gateway for the exchange of resources, services and more.

Xinjiang Supports the Belt and Road Development Plan

An official from the Xinjiang Development and Reform Commission told HKTDC Research that Xinjiang had started making far-reaching plans in accordance with the Belt and Road Initiative. Although concrete implementation details are still being worked out and examined, a general strategy of developing five centres and three corridors has been adopted.

The five centres refer to a transportation hub, a trade and logistics centre, a financial centre, a culture, science and education centre, and a medical services centre. The last of these will provide medical services to Central Asian countries. According to a Xinjiang official, medical standards in Xinjiang are higher than in Central Asia and over 1,500 people from neighbouring countries received medical treatment in Xinjiang in 2015. As well as Urumqi, hospitals in the border regions also received patients from these countries. The combination of medical services and a tourism offering is a possible area for future development.

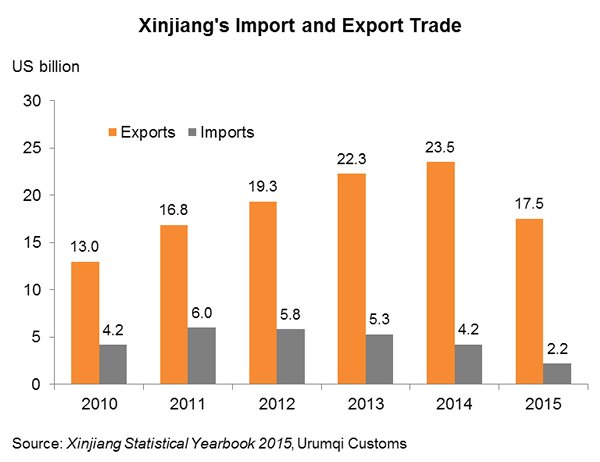

The transportation hub and trade and logistics centre are actually interrelated developments. Xinjiang mainly trades with Central Asia. Xinjiang's total import and export value dropped to US$19.68 billion in 2015 due to falling demand in that region. The fact that import/export trade with Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan accounted for 46% of Xinjiang's total trade value and Xinjiang's trade with the Central Asian countries made up a big share of China's trade with these countries indicates that China's trade with Central Asia is mainly conducted through Xinjiang, although many of the export goods originate from coastal and inland provinces.

Aside from trading, Xinjiang also functions as a transportation corridor. Some of the goods imported or exported are not handled by local trading companies but shipped to Central Asia or imported from Central Asia through Xinjiang. According to Xinjiang's customs statistics, the volume of cargoes handled by Xinjiang's ports in recent years increased from 20.93 million tonnes in 2009 to 46.65 million tonnes in 2014, while the total value of imports and exports increased from US$22.29 billion to US$46.14 billion in the same period, exceeding the import and export figures of local trading firms.

Xinjiang to Become A Regional Transportation Hub

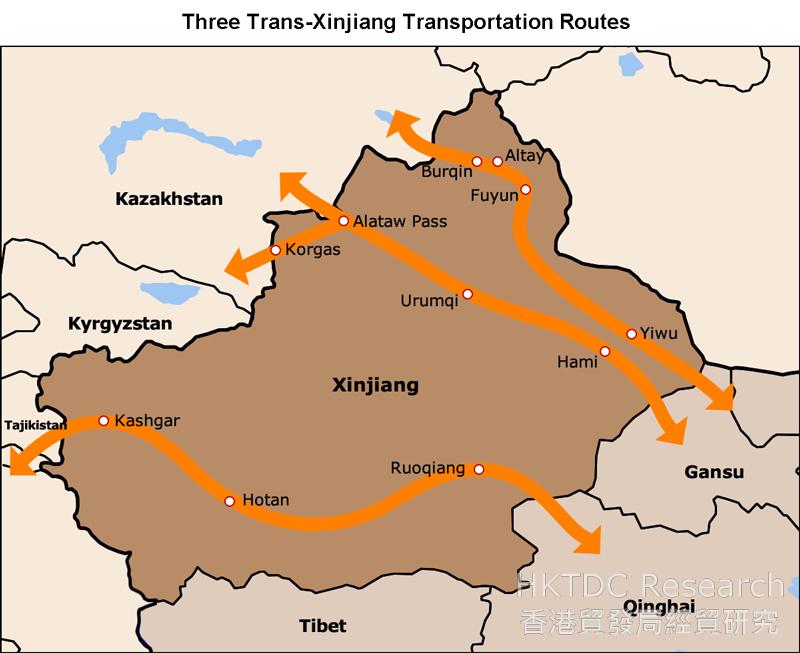

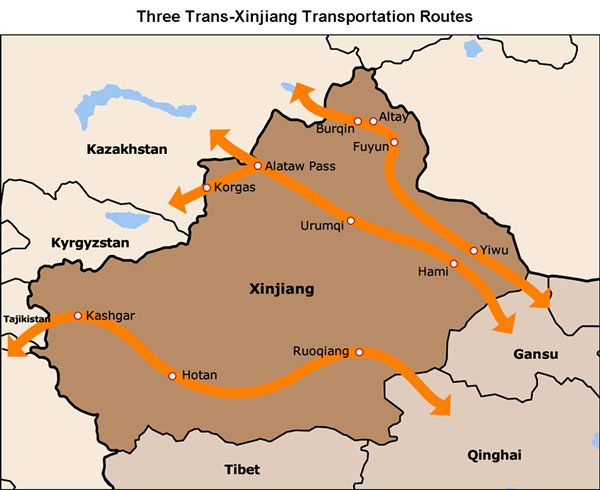

Although Xinjiang faces challenges from weakening demand in its foreign trade in recent years, it still has the geographical advantage of being the corridor for transportation and logistics between the Chinese mainland and Central Asia. For this reason, Xinjiang aspires to become a regional transportation hub under the Belt and Road Initiative. The main priority is to develop three transportation routes across Xinjiang to cities in Central Asia, West Asia, South Asia, Russia and other countries.

The northern route originates from the Bohai Rim. Starting from Beijing-Tianjin-Tanggu, it runs across Shanxi province and Inner Mongolia before reaching Xinjiang, where it runs westwards to Kazakhstan and Russia via Yiwu, Burqin and other counties. The middle route starts from the Yangtze River Delta region and runs across the Central Plain via the second Eurasian land bridge before entering Hami, Turpan and Urumqi in Xinjiang, from where it proceeds to Central Asia and Europe via Alataw Pass and Khorgas respectively. The southern route starts from the Pearl River Delta region and runs across Hunan, Chongqing, Sichuan and Qinghai before entering Xinjiang, where it leads to Tajikistan via Ruoqiang, Hotan and Kashgar and extends southwards to the Indian Ocean coast. According to the Xinjiang Development and Reform Commission, the middle route is already open to traffic and is undergoing further upgrades. As for the other routes, the portions in Xinjiang are expected to be opened to traffic during the 13th Five-Year Plan period (2016-2020).

An Entrepôt and Distribution Centre

Relying on its transportation links, Xinjiang aspires to become an entrepôt and distribution centre for goods flowing between Central Asia and the Chinese mainland. In particular, smaller cargoes can be consolidated here and loaded on containers. The railway container centre now under construction in Urumqi is a major project and it is hoped it will speed up the integration of China-Europe train services, build the city into a westbound container shipping centre and spur the building of logistics parks in neighbouring areas. Xinjiang is striving to open more freight train services and reshuffle train schedules in order to enhance its function as a distribution centre. It will also build national highway transport hubs and more than 30 logistics parks in Urumqi, Yining and other cities in the next five years.

Yining also plans to renovate and expand the existing terminal at its airport during the 13th Five-Year Plan period. It will open an international immigration checkpoint at the airport, establish international air routes to Kazakhstan and other Central Asian cities, begin freight transport targeting Central Asia and build an international logistics centre. At this stage, whether the entrepôt and distribution centre project will materialise depends on whether there is a steady supply of cargoes. According to the Xinjiang Development and Reform Commission, Xinjiang will have to rely on its integrated bonded areas, free trade areas, railways and air transport and also strengthen its function as a distribution centre to attract high cargo volumes.

International Logistics Potential Merits Attention

Xinjiang's development as a transport logistics and distribution centre linking the Chinese mainland and Central Asia, even Europe, is worthy of note. From the perspective of international logistics, infrastructure developments will likely change the present reliance on maritime transport for shipments to Europe. Xinjiang's unique geographical advantage as a buffer between China and Central Asia/Europe and the fact that its ethnic minorities have close cultural ties with people in Central Asia will only enhance its prospects in this area.

Overland transport between Central Asia and Europe has started to develop in the last two years. When cargo volumes increase, demand for transshipment, consolidation and distribution will also increase, thus allowing Xinjiang to further strengthen its hand by providing such services. Providing a gateway for the export of goods to Central Asia and Europe will increase the demand for relevant logistics services, while enhancing its function as a consolidation and distribution centre will also stimulate demand for service management systems in Xinjiang. Moreover, with the development of cross-border e-commerce, it will also have a chance to become a warehousing and distribution centre for coastal manufacturers supplying goods for Central Asia’s e-commerce markets.

Local Processing Industry To Serve Central Asian Markets

In addition to handling goods manufactured in the coastal and inland provinces, Xinjiang also plans to encourage the development of local processing. Besides serving as a base for the production, processing and storage of oil and gas, as a base for the coal power and coal chemistry industry, and as a base for wind power, Xinjiang plans to develop processing industries, with local resources or semi-finished materials made elsewhere being used to produce goods for markets in Central Asia. Resources such as timber, cotton and corn from Central Asia might also be used to produce timber, furniture and other products for re-export to Central Asia or other parts of China.

According to the authorities concerned, the automobile equipment industry is a key one for the Urumqi Economic and Technological Development Zone. Mainland manufacturers have set up business there mainly due to its proximity to Central Asian markets. Export convenience was cited as a key consideration in deciding to set up in Xinjiang by one Guangdong motorcycle plant. Increased transport links between Xinjiang and the central and coastal cities have greatly improved its logistics and connectedness with other regions, making it possible for processing industry manufacturers in Xinjiang to obtain materials and other support from other regions at a lower cost.

To encourage the use of local cotton resources, Xinjiang has introduced policies to support the development of textile and garment industries in recent years. Besides building textile and garment bases in Aksu and Korla in southern Xinjiang and Shihezi in northern Xinjiang, it has also supported the development of printing and dyeing. A special fund for the development of textile and garment industries has been set up to subsidise transportation expenses, staff training, social insurance payments and sewage treatment. In view of the relative weakness of the local supporting industries, Xinjiang plans to develop textile sectors with a short industry chain, such as knitting, carpet-making and home textiles.

|

Food processing company Tsinfood chose to set up a factory in the Urumqi Export Processing Zone to produce tomato sauce, fruit jam, canned vegetables, seasoning and other products. Locally grown fresh tomatoes are used to produce tomato sauce. Besides having its own plantations, Tsinfood also outsources to local farmers to produce the ingredients needed. Tsinfood mainly exports its products to Kazakhstan. It has established an R&D base to develop products catering to people in Central Asia. For example, Kazakh consumers have a sweet tooth. Because of the relatively backward manufacturing techniques in Kazakhstan, Tsinfood's recyclable jam bottles are welcomed by local consumers. Today Tsinfood products have a market share of 25-30% in Kazakhstan. The company has even found its way to Uzbekistan and Russia through Kazakh agents.

Tsinfood also has a factory in Almaty, Kazakhstan. The two factories produce similar products. The raw materials (such as tomato sauce) and other supplies needed in the Kazakh plant are shipped from Xinjiang. The company in Almaty is mainly responsible for receiving orders. Although most of the products made at this tomato processing plant are for export, it has begun to sell some of its products to the mainland market in recent years.

|

According to local authorities, land costs and electricity tariffs are relatively low in Xinjiang. Despite the availability of workers locally, training is needed, while wage levels are not significantly lower than in other mainland cities. The Urumqi Economic Development Zone admitted there is a shortage of skilled labour but said it was cooperating with local vocational and technical colleges to train the necessary personnel. It is understood that ordinary workers are paid about RMB3,000 a month.

Some development zones are offering preferential policies. For example, the Yining Industrial Park of the Khorgas Economic Development Zone, kick-started in 2013, is currently focusing on infrastructure construction. It aims to become a regional commercial logistics centre, develop processing industries and export the products to Central Asia. According to the authorities, if enterprises setting up business in the park are engaged in industries prioritised by the state, they are eligible for exemption on enterprise income tax in their first five years and for exemption on the local retention portion of it for a further five years. Tariffs are waived for the import of equipment that is not produced in China. Discount interest loans are available for fixed assets/working capital and subsidies are offered for staff training (especially for the labour-intensive textile and garment industries). The approved land price is RMB150,000/mu.

The State Council issued its Opinions on Several Policy Measures in Support of the Development and Opening-up of Key Border Regions in January 2016. The document called for efforts to promote dominant industries with regional characteristics in the border areas. It also supported giving priority to projects for the processing, transformation and utilisation of imported energy resources and resources in key border areas in an effort to develop outward-oriented industry clusters in these areas. Moreover, the document proposed setting up a special fund for the development of industries in key border areas. These policies show the importance given by the central and local governments to the promotion of industrial development in the border areas. Xinjiang may not be the most suitable destination for the relocation of most processing industries because of its geographical location and other factors. However, for processing industries that make use of local resources and ones imported from Central Asia, and enterprises targeting the Central Asian and South Asian markets, Xinjiang merits consideration, particularly in light of Belt and Road Initiative developments.

| Content provided by |

|

Editor's picks

Trending articles

‘One Belt, One Road’ - An Opportunity for the EU’s Security Strategy

by Jikkie Verlare & Frans Paul van der Putten (Clingendael Institute)

China’s initiative for a modern-day silk road, known as ‘One Belt, One Road’ (OBOR), aims to connect Asia, Africa, Europe and their near seas. Under the definition contained in Xi Jinping’s New Security Concept stating that ‘development equals security’, OBOR can be conceptualized as the most ambitious infrastructure-based security initiative in the world today. This has major implications for geopolitical relations and stability in various regions. It would be beneficial for the European Union (EU) member states to invest in a common response to OBOR, as opposed to engaging with this initiative primarily at the national level. This Clingendael Policy Brief explores how the EU’s existing policy tools and frameworks might be used for enhanced Sino–European security co-operation in relation to OBOR. It is argued that if the European Union works with China under the framework of the EU–China strategic partnership, to align with, inter alia, the planned restructuring of its European Neighbourhood Policy, as well as projects included under its European Maritime Security Strategy and Partnership Instrument to link with the so-called ‘Belt’ and ‘Road’ projects, this would entail true added value for the EU. These steps should be part of the EU’s new Global Strategy for Foreign Policy and Security, which is due to be published in June 2016. This would go beyond the tendency of EU member states to compete for the benefits of increased Chinese investments on their own territories, but instead embed China’s initiative in the common European strategic goal of gaining a larger security footprint in neighbouring regions…

Please click here for the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

A New Opportunity in EU–China Security Ties: The One Belt One Road Initiative

by Jikkie Verlare (Clingendael Institute)

China’s Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road initiative aims to connect Asia, Africa, Europe, and their near seas. The purpose of this study is to examine whether it would be beneficial for the European member states to invest in a common response strategy to the One Belt One Road, as opposed to engaging this initiative primarily at the national level. After exploring how the EU’s deteriorating security environment has caused member states to attach more importance to maintaining the EU’s defence and power projection capabilities, the paper turns to the strategies currently employed to gain more influence over security matters in East Asia. Upon examination, it is shown that three out of four approaches hold little promise of progress. (1) Engagement with ASEAN will only reach its full potential when its integration process is completed, (2) expanding consultations with the US might lead to the perception of a ‘dependent’ Europe and loss of neutrality, and (3) a lack of hard power means that the EU is often not taken seriously as a security actor when participating in regional forums. The remainder of the paper explores the opportunity that has surfaced with regards to the fourth approach: utilising the EU’s strategic partnerships in Asia. Under the definition contained in Xi Jinping’s New Security Concept stating that ‘development equals security’, China’s One Belt One Road initiative can be conceptualized as both the most ambitious infrastructure and security initiative today. It is argued that if Europe works with China in the framework of their strategic partnership to align, among others, the planned restructuring of its European Neighbourhood Strategy, as well as projects included under its European Maritime Security Strategy and Partnership Instrument to link in with the Belt and Road projects, this would entail a true added value for the EU. Doing so will enable members states to not just compete for the benefits of increased Chinese investments on their own territories, but embed China’s initiative in their own strategic goal of gaining a larger security footprint in the Asian region…

Please click here for the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

One belt one road - China's new outbound trade initiative

By Carolyn Dong & Simin YU (DLA Piper)

China’s 'One belt one road' initiative was first introduced by President Xi Jinping during his visits to Central and Southeast Asia in September and October 2013. With the dawn of 2016, it is appropriate time to take stock and review what has been done so far in implementing the initiative, and its future direction.

Set out below is an overview of the One Belt One Road (shortened to OBOR) initiative. As detailed further below, with the initiative successfully launched, key funding institutions established, a regulatory framework deployed and eager diplomats entering into multiple bilateral agreements across the globe, 2016 is now likely to see a rapid acceleration in the uptake of OBOR projects. The potential now exists for powerful partnerships to be established between international and Chinese enterprises to leverage off this initiative.

'One belt, one road' in a nutshell'

'One belt, one road' is a development strategy and framework, proposed by the highest levels of PRC Government that focuses on connectivity and co-operation among countries along two main routes, the land-based 'Silk road economic belt' and oceangoing 'Maritime silk road' which run through the continents of Asia, Europe and Africa, connecting vibrant East Asian economies at one end and developed Western European economies at the other, while encompassing more than 65 countries along the route. The OBOR initiative covers countries as diverse as Singapore, Georgia, Kenya and the Netherlands.

The strategy underlines China's push to take a bigger role in global affairs, and its need to export China's production capacity in areas of overproduction such as steel manufacturing and infrastructure construction. However, the OBOR initiative is a broad initiative and captures everything from regional arts festivals and book fairs through to the establishment of the $100 billion Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the $100 billion BRICS New Development Bank and the $40 billion Silk Road Infrastructure Fund. In March 2015 China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Commerce jointly issued the Visions and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Centruy Maritime Silk Road ('Visions and Actions Plan') for the OBOR initiative, which, similar to a strategy paper, acknowledges that the OBOR is a pluralistic and open process of co-operation which can be highly flexible and does not seek conformity.

However, at its core OBOR demonstrates a high level political commitment in China to work with participating countries to facilitate an increase in trade and investment flows and interconnections. A key focus of this is on reducing barriers to trade – both overcoming literal barriers (such as inadequate port, rail and road infrastructure) and also overcoming less tangible barriers (such as enhancing trade liberalisation and easing customs and quarantine processes).

OBOR calls for an improvement on the region’s infrastructure, with a call for greater energy and power interconnections and to establish a secure and efficient network of land, sea and air passages across the key routes. Additionally, the initiative calls for greater policy co-ordination (such as opening free trade areas and improving co-operation in new technologies) and financial integration (such as carrying out multilateral financial co-operation in the form of syndicated loans and supporting foreign countries to issue RMB denominated bonds). Furthermore, whilst the OBOR is firmly rooted in the Silk Road’s thousand year old heritage, it also clearly looking to the future – greater e-commerce interconnectivity and advancing the construction of fibre optic cables is encouraged.

OBOR: 2+ years down the road

Since OBOR’s 2013 launch, we have seen the successful launch of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the $100 billion BRICS New Development Bank and the $40 billion Silk Road Infrastructure Fund (SRF). The former two institutions (AIIB and BRICS New Development Bank) are not exclusively directed towards the OBOR (although they are indeed relevant), but the latter, SRF, as the name suggests, has OBOR projects as a prime focus. Moreover the SRF has already started being a particularly active investor along the OBOR routes. For example, in April 2015 the SRF announced its first OBOR investment project – Pakistan’s 720-MW Karot hydropower project. In June 2015, the SRF (together with one of China’s largest chemical enterprises, ChemChina) announced agreements to seek to acquire Italian tyre manufacturer Pirelli. In September 2015, SRF concluded a framework agreement with one of Russia’s leading independent gas producer, Novatek, on the acquisition by SRF of a 9.9% equity stake in the Yamal LNG project. The SRF has also been an active investor in recent Hong Kong initial public offerings, taking cornerstone stakes in each of China International Capital Corporation’s October 2015 IPO and China Energy Engineering Corporation’s November 2015 IPO.

Other projects announced in connection with the initiative include a number of private Chinese companies’ foreign expansion and joint venture plans in a OBOR countries, such as the strategic co-operation agreement between Anhui Conch Cement and the Bank of China to see Anhui Conch Cement investing to establish new project sites in South East Asia; and machinery maker XCMG Group’s opening of new joint venture factories in Uzbekistan.

Additionally, Chinese regulators have continued to lay the regulatory and diplomatic foundations to support the OBOR initiative. Domestically, under the guidance of the March 2015 of the Visions and Actions Plan (which lays out the broad strategy of the initiative (see above)), 2015 saw other key Chinese regulators issue supporting guidance. This included China’s State Administration of Taxation releasing the 'Notice Regarding the Tax Services and Administration to Implement the Development Strategy of the ‘One Belt One Road’' regarding tax services and improvements contemplated for the OBOR route and the Ministry of Transport drafting supporting plans and measures. Additionally a number of Chinese provinces have published guidance notes and plans relevant to their local areas, for example Guangdong (June 2015); Hunan (August 2015); and Henan (December 2015). Each of these localised plans focuses on the geographical benefits and respective strengths of each province. For example the Guangdong plan focuses on developing shipping and cross-boundary infrastructure in the Pearl River Delta (covering the Guangdong-Shenzhen-Hong Kong and Macau bay area); whilst the inland province of Henan plans on positioning itself as an access point for the opening up of China's inland regions to the outside world.

On the international front, China’s diplomats have been busily engaging with relevant counterparties, with international agreements or memoranda issued jointly with countries as diverse as India, Hungary, Kazakhstan and Russia.

Successfully utilising OBOR opportunities

A large portion of China’s foreign investment and trade going forward are expected to take place in OBOR countries. However, the OBOR is not only outward looking from China - it is a two-way street, with the Visions and Actions Plan specifically welcoming companies from all countries to invest in China whilst also encouraging Chinese companies to participate in infrastructure construction and undertake other investments in other countries along the route.

Key industries for the OBOR initiative include: infrastructure and projects; energy and power; transport and logistics; information technology and industrial development; and financial markets.

Successfully implementing projects along the OBOR will not be without risks and challenges. Overcoming these risks will require thorough due diligence exercises and robust partnership and joint venture arrangements. More importantly success will depend on enterprises finding the right partners and having the right support networks providing a thorough understanding of local conditions, regulators, market players and, more generally “ways of doing business” in both China and the foreign host jurisdictions. This will be essential to be able to adequately identify, quantify and overcome risks and opportunities; to achieve this, an on the ground presence and knowledge of suitable partners and relevant contacts (both for foreign parties in China; and for Chinese parties in the foreign jurisdiction) is a perquisite.

Importantly, whilst China has allocated significant capital and resources towards implementing OBOR, China cannot implement the OBOR alone. Success of this initiative requires co-operation between Chinese enterprises and foreign counterparties in a raft of sectors and regions, covering everything from small scale trade and investment, to the delivery of large scale multi-jurisdictional game-changing infrastructure... and consequently the OBOR initiative offers countless opportunities for foreign companies to partner with Chinese companies, enterprises and financial institutions.

Please click to view this article on the DLA Piper’s website.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Treading softly along China’s “One Belt, One Road”

By Julian Vella (Asia Pacific Head of Global Infrastructure, KPMG International)

China’s bold vision can make a significant contribution to bridging the Asian infrastructure investment gap. But Chinese investors should be aware of the heightened expectations that come with selecting and managing projects in new markets.

Over 2000 years ago, the Silk Road was established as a trade route connecting China with Eurasia and the mighty Roman Empire. The road, in various forms, lasted over 1500 years before a decline in political powers ended its influence. Fast-forward half a millennium, and China’s plan to rebuild its old trade links with Europe and Asia has aroused renewed excitement.

The “One Belt, One Road” initiative envisages a path by land from China through Central Asia to Europe, with the maritime route flowing through Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean, the Middle East, and Africa to Southern Europe.

By building essential infrastructure and boosting financial and trade links, the belt and road aims to enhance commerce and spread prosperity across 60-plus countries with a combined population well in excess of 4 billion. Financing comes from a number of sources, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the Bank of China, The China International Trust & Investment Corporation, (Citic), and the Silk Road infrastructure fund. To date, approximately 250 billion dollars (US$) of related projects have been contracted, much of them involving Chinese machinery, raw materials and construction firms.[1]

Choosing the right projects

Given its huge domestic development in recent decades, China is hardly a newcomer to managing major projects. However, taking its infrastructure show on the road, across such a diverse range of countries, raises a number of fresh challenges.

Firstly there is the sensitive issue of sovereignty. With China emphasizing that it will respect sovereign rights, project selection will in many cases be at the discretion of each of the nations along the route – whose priorities may or may not align with those of China. A proposed railway line that stretches through to Thailand, for example, could support the latter’s ambitions to become a regional logistics hub, and the former’s need to access key export markets, offering a win-win for both countries. On the other hand, some prospective projects could potentially be viewed as primarily benefiting either China (e.g. by securing its energy resources) or the country in question (e.g. building local infrastructure unrelated to the One Belt route). Under any circumstances, choosing the right projects to prioritize can be quite a challenge. When dealing with governments inexperienced in infrastructure development this is compounded, particularly as project selection can often become highly politicized. When you factor in concerns over lack of transparency, corruption, an uncertain legal and regulatory environment, unpredictable financial systems and foreign exchange exposure risks, then decisions become even more complex. China’s domestic infrastructure program has been largely government financed, and carried out at breathtaking pace to accelerate economic growth. Conducting projects outside of its borders, in emerging markets, is a far more complex and prolonged affair, with the involvement of an array of stakeholders, which can slow the pace considerably.

These issues make it doubly difficult to please financiers (either banks or funds), who expect a good return on their investment through carefully chosen, efficient and well-managed projects. Project leaders, must, therefore, show a high level of understanding of the unique regulatory, political, legal, financial and project risks associated with potential projects, such as resource nationalism, transparency and labor unrest. It’s especially important to earn a ‘social license to operate’ by creating a good working environment, contributing to communities and minimizing the carbon footprint.

Amidst this complexity, China should, therefore, exert ‘soft’ power through comprehensive and early engagement with all governments along the route, to ensure that every project is positioned as a collaborative venture that brings rewards to all parties. This may involve investment in areas of infrastructure that do not directly benefit China, such as healthcare, education and housing.

A new game with different rules

Chinese businesses have relatively less experience in managing overseas projects, except where they are directly tied to China’s economic and trade objectives. This opens up opportunities for players from more mature infrastructure markets such as Australia, UK and Canada, to offer new ideas and technical knowledge as part of their project development and project management support. With its recent US$880 million acquisition of Australian construction giant John Holland, The China Communications Construction Company (CCCC) has gained access to invaluable technical expertise; a move that could be replicated.

Hong Kong also has a significant role to play in supporting infrastructure development as well as facilitating trade and investment along the belt and road given its location, its connectivity with mainland China, and its strength in financial services, transport and logistics, and professional services.

In addition, Chinese investors must also acknowledge that some of the countries in the proposed route have traditionally strong links to other nations with a vested interest in the region, and may resist China’s overtures. Equally these powers, namely Japan, India and especially Russia (which has a big influence in central Asia) may not support China’s efforts, and could seek alternative trade routes and blocs. Japan has not signed up to the AIIB, having nailed its colors to the mast of the established Asian Development Bank (ADB) as one of the largest shareholders. Since the One Belt announcement, Japan has stepped up its game, pledging to increase its investment in the ADB by US$110 billion over 5 years, with an expressed intent to build infrastructure such as roads and railways while reducing pollution.[2]

India, meanwhile, has its own programs, namely the Spice Route between Asia and Europe, and the ‘Mausam’ project that revives ties with its ancient trade partners via the Indian Ocean, stretching from east Africa, along the Arabian Peninsula, past southern Iran to South Asia, Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia.

While commentators have sought to describe the “One Belt, One Road” in various ways, it is clear that the initiative does reflect the Chinese government’s recognition that its own prospects are inextricably linked with those of its trading partners, and that it must take a more global role to further these ambitions.

With an annual Asian infrastructure gap estimated to be US$800 billion[3], there is plenty of room at the table for the AIIB, the ADB, and, indeed, other interested investors from around the world. The ADB has said that it is prepared to co-operate with China and has welcomed the entry to the region of new institutions for funding and supporting development projects. Despite fears that the main players are trying to assert an unhealthy influence, their combined efforts can make a real contribution to sustainable, inclusive growth for dozens of emerging economies.

Please click to download the original PDF file on KPMG’s website.

[1] China’s ‘One Belt, One Road’ looks to take construction binge offshore, Reuters, 6 September 2015.

[2] Japan unveils US$110 billion plan to fund Asia infrastructure, eye on AIIB, Reuters, 21 May 2015.

[3] Building China’s “One Belt, One Road,” Center for Strategic & International Studies, 3 April 2015.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Estonia: A Switched-on, Tech-Savvy Baltic Partner

While having the smallest population of the three Baltic States, Estonia is nevertheless the region’s ICT powerhouse, besides being one globally in many ways too. Innovative e-solutions and the omnipresence of high-speed internet and wi-fi services are good examples of how a tiny, post-Soviet nation has created the enabling conditions for an information society. This goes hand in hand with its strategic location in terms of regional logistics and Eurasian connectivity.

Given its small domestic market, innovative Estonian companies with ambitions to grow have to go beyond the country’s borders for development and expansion. Hong Kong can therefore be an ideal catalyst for Estonian companies that wish to exploit opportunities in Asia, especially under the umbrella of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Estonia as E-stonia

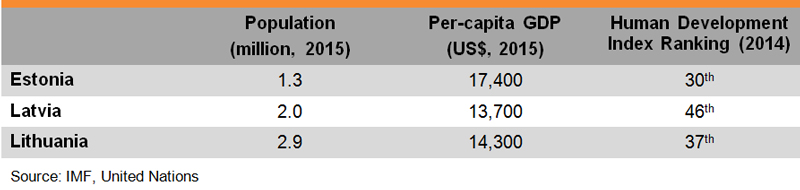

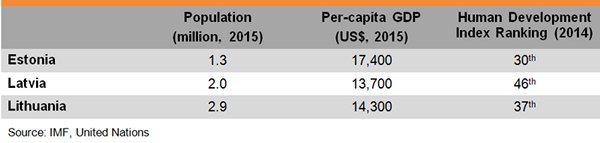

Among the three Baltic States, Estonia is the richest in terms of per-capita GDP, and also the highest ranking in the United Nations’ Human Development Index. Thanks to a forward-thinking government, a pro-active ICT sector and a switched-on, tech-savvy population, Estonia, a small country along the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, has gained worldwide recognition for its digital economy. It has developed pioneering e-government initiatives, a high degree of cyber-security and groundbreaking e-solutions to daily life problems.

Even in Soviet times, radio-electronic and semi-conductor industries were well developed in Estonia. Following the formal declaration of independence in August 1991, the country underwent rapid economic transformation characterised by a favourable taxation system, free trade and large-scale privatisation.

The Estonian government has been very supportive of the country’s ICT industry and the country hosts both the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence and the new headquarters of the European Agency “for the operational management of large-scale IT systems in the area of freedom, security and justice”, EU-LISA. Deeming it a basic human right, the government also made free wi-fi the norm throughout the country back in 2000. And it has incorporated data privacy and security protections into national laws to bolster long-term technology development and future ICT advances.

From developing the code behind Skype, Hotmail and Kazaa (a peer-to-peer file sharing application) to numerous e-government initiatives, Estonia continues to excel in terms of next-generation e-solutions that make a difference at a grassroots level, connecting people with people, with the state and with the wider world. As a member of Digital 5 (D5), a network of digital governments who share the goal of strengthening the digital economy, Estonia (together with Australia, Singapore, South Korea and the UK) presents a wealth of possibilities not only for business, but also for cooperation between governments and between business and government in the era of e-government.

Nowadays, 99% of bank transfers are performed electronically in Estonia, where many young people have never seen a cheque or cheque book in their lives, while 95% of income taxpayers file their annual tax returns online. In addition to banking and taxation, 98% of medicines are prescribed electronically and 66% of the population participated in the country’s last census online. As the world’s first country to allow online voting in a general election, in 2007, more than 30% of votes cast by Estonians in the 2014 EU Parliament elections were done so online.

Also in 2014, Estonia became the first country in the world to offer e-residency — a transnational digital identity. With 10 million e-residents targeted by 2025, it is open to anyone in the world interested in administering a business online. E-residents can sign and verify documents and contracts digitally, conduct e-banking, make remote money transfers and pay Estonian taxes online. They can effectively run an Estonian company online and administer it from anywhere in the world.

The e-residency and its embedded digital signature allows people to perform most business and personal transactions online, except for marriage, divorce and sales of property. This initiative is a big help to many international financial and technology companies looking for new platforms or markets in which to conduct R&D. Since May 2015, Estonia has allowed online e-resident applications and payment for a smart ID card. So far, the initiative has been best received by applicants from Finland, Russia and the US – countries where Estonian ICT and knowledge-based companies are accustomed to seeking out partners and venture capital.

Strong ICT Sector and Strategic Location

In ancient times, goods bound for Scandinavia which had travelled the Silk Road went through Estonia. In addition to its distinct geopolitical location, Estonia is again proving an increasingly important logistics platform for moving goods, knowledge and people from east to west. Combined with the country’s strong ICT background, this makes Estonia a ready candidate for greater regional and inter-regional integration, in keeping with the BRI.

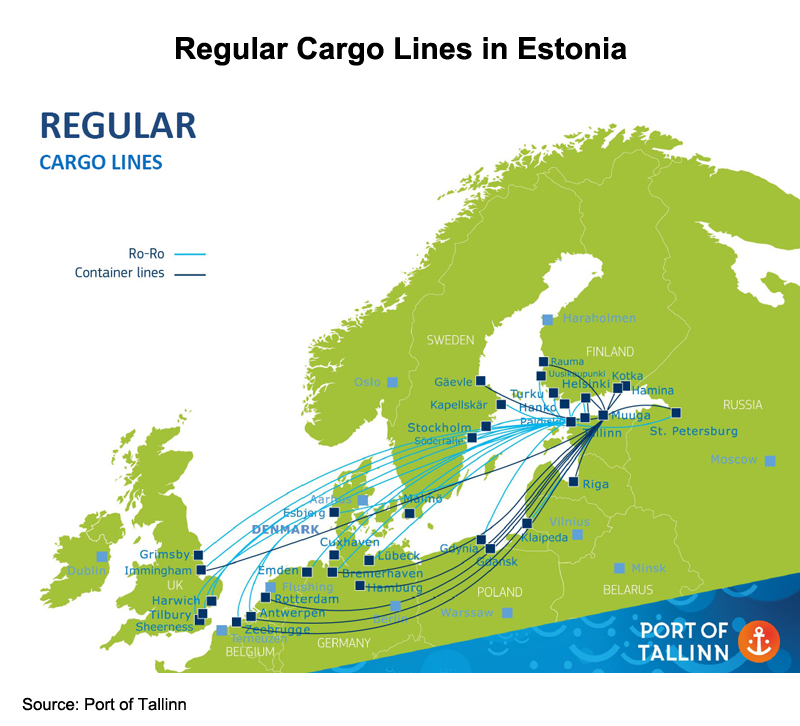

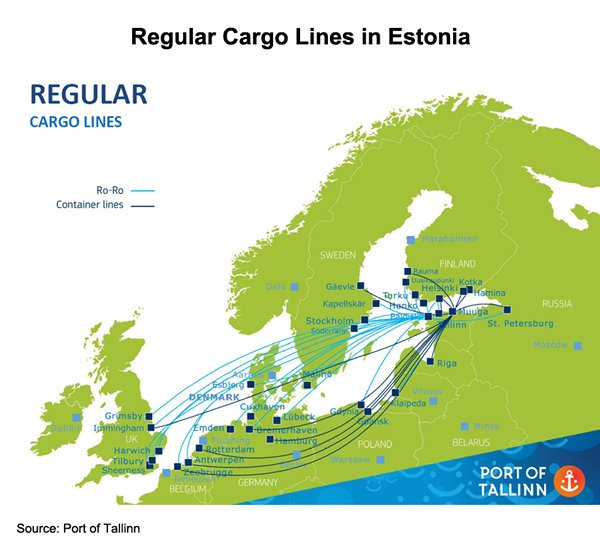

Situated on a busy trading route between East and West, Estonia operates nearly 30 well-developed ports. Among them, the five harbours (Old City Harbor, Muuga Harbour, Paldiski South Harbour, Paljassaare Harbour and Saaremaa Harbour) operated under the umbrella of the state-owned Port of Tallinn (a port authority rather than a single seaport) constitute the nearest Baltic ports to Russia (apart from the exclave of Kaliningrad, which is surrounded by Poland and Lithuania). Altogether the Port of Tallinn handled 22.4 million tonnes of cargo, 208,784 containers and 9.8 million passengers in 2015, when 1,684 cargo ships and 5,397 passenger ships called in.

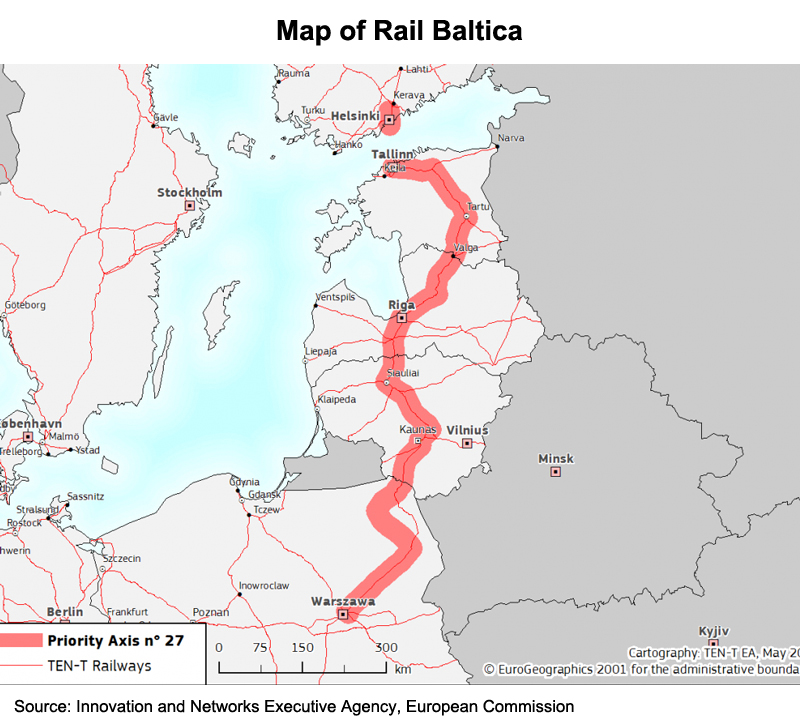

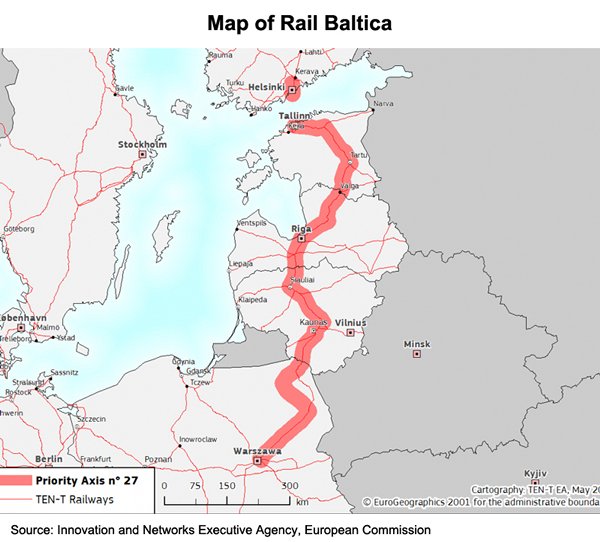

With the aim of connecting the peripheral Baltic States to “the heart of Europe”, the European Commission in 2004 initiated Rail Baltica, a strategic project linking Estonia (Tallinn), Latvia (Riga), Lithuania (Kaunas, Vilnius) and Poland (Warsaw), with the route also set to be extended to countries such as Germany (Berlin) and Italy (Venice) in the future. Rail Baltica is a Trans-European Transport Networks (TEN-T) Priority Project.

It is also the first step in the Baltic countries’ transition to European railway-gauge standards. With road transport accounting for more than 97% of total cargo flows between the Baltic States and Poland, it creates the possibility to shift the heavy freight traffic between Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and the rest of EU from road to rail, in turn helping to reduce commuting times, traffic congestion and air pollution. With the signing of a memorandum of understanding (MOU) on 5 January 2016 to build a 92km underwater tunnel connecting Tallinn and Helsinki, for example, the commuting time will be slashed by 70%, from 100 minutes to 30 minutes, upon completion.

As regards air transport, Estonia recently earmarked €40.7 million (or HK$346 million) as initial capital for a new, fully state-owned carrier, after the ailing Estonian Air was found to be in breach of the EU’s state-aid rules and ceased operations as of 7 November 2015. Estonia also plans to team up with regional air hubs such as Helsinki in Finland for more regional air services cooperation. This will help compensate for the loss of business due to Estonia Air’s wind down, while also enhancing the country’s air connectivity for both freight and passengers.

Together with its strong ICT background and infrastructure, Estonia’s strategic location and enhanced multimodal connectivity provide a fertile breeding ground for cross-border e-commerce businesses. In September 2015, the state-owned Estonian postal company, OMNIVA, signed an MOU with S.F. Express, China’s largest private-capital-funded courier company, to set up a joint venture called Post11. This includes warehouses in Estonia to make the import and export of goods between China and Europe faster and more efficient. The joint venture will first focus on the delivery of goods from China to the Baltic States, Russia, Ukraine and the Scandinavian countries, before extending its reach to the whole of Europe.

With nearly half of all the goods Estonians order from abroad coming from China, the joint venture and its new supply chain solutions will likely strengthen Sino-Estonian and Sino-European e-commerce as cooperation between Chinese e-stores and Estonian ICT and logistics solutions becomes more seamless.

Ready for the BRI

Constrained by its small population, Estonia is no longer positioning itself as an ICT manufacturer as it did during the Soviet times. Boasting one of the world’s highest per-capita business start-up ratios, it is, however, aiming to strengthen a dynamic and competitive knowledge-based economy, providing an environment for ongoing digital success stories.

Hong Kong, as Asia’s top IP and technology marketplace, can be an ideal trading platform for Estonian technology and innovative e-solutions. Its easy access to equity financing and its robust legal and IP regimes can also help Estonian startups looking for venture capital, local business opportunities and strategic partners.

As a pioneer in cyber-security and many e-government initiatives, Estonia has companies which can be ready partners for Hong Kong’s professional services providers and financial institutions, especially with regard to the development of FinTech. It is reported that one Russian company is looking to connect Estonian tech startups with investors from Asia via Hong Kong, while also marketing their technology and practical e-solutions to big financial services clients located and headquartered in the city.

Aside from technology and financial opportunities, Estonia’s ongoing improvement in its multimodal connectivity is also conducive to the successful implementation of the BRI, which aims to facilitate and promote greater integration among the 60-plus countries along the Belt and Road. The economic ties between Estonia and China will also be strengthened through membership of the “16+1” formula [1].

Hong Kong’s connectivity with much of Asia, its privileged free-port status and its cost-effective multimodal logistics options are helping Estonian companies reach out to Asia. This role will be further strengthened as the Second Eurasian Land Bridge takes shape and new railway routes are established. In particular, the recent opening in Hong Kong of the development office of KTZ Express, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Kazakhstan Railways, in order to promote multimodal freight logistics through Kazakhstan between Europe and China, indicates the city’s key role in Belt and Road logistics.

[1]In 2011, China revived its cooperation with a group of 16 Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Albania and Macedonia. In 2012, the first meeting at the level of heads of government was held in Warsaw, marking the official launch of the “16+1” formula.

| Content provided by |

|

Editor's picks

Trending articles

A Belt and Road Development Story: Trade between Xinjiang and Central Asia

Geographically, Xinjiang borders a number of Central Asian countries, including Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. With improved transportation and access, Xinjiang's ports have become China's coastal and central regions’ gateways for export to Central Asia. According to Xinjiang's customs statistics, the freight volume of its ports increased from 20.93 million tonnes in 2009 to 46.65 million tonnes in 2014, while the total value of their imports and exports soared from US$22.29 billion in 2009 to US$46.14 billion in 2014.

A Vital Role in China’s Trade with Central Asia

Besides functioning as a transportation channel, Xinjiang also serves as a trading platform for Chinese goods destined for Central Asia. Although market demand in Central Asia weakened in 2015 due to economic, exchange rate and other factors, Xinjiang's exports of light industrial products, machinery and electronic products, as well as of processed food, continued to grow thanks to rising demand for Chinese products in the Central Asian markets over the last few years. In addition to local products, buyers from Central Asia are also eager to source goods manufactured in other parts of China, including the Yangtze River Delta and Pearl River Delta regions. This makes Xinjiang a trading platform for sales to Central Asia.

Xinjiang mainly trades with the Central Asian countries. Customs statistics show that as a result of falling demand in Central Asia, Xinjiang's total import and export value dropped to US$19.68 billion in 2015. However, the fact that import/export trade with Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan still accounted for 46% of Xinjiang's total trade value and Xinjiang's trade with Central Asian countries still accounted for a big share of China's trade with these countries suggests that most of China's trade with Central Asia uses Xinjiang as an intermediary. It also indicates that most of the export goods come from China's coastal or inland areas.

A large proportion of China's exports to Central Asian countries are handled by companies in Xinjiang, including both local firms and agents of other mainland enterprises. In 2015, Xinjiang's exports to Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan accounted for 62.3%, 74.7% and 76.7%, respectively, of China's exports to these three markets, reflecting Xinjiang's crucial role in China's trade with Central Asia.

“Border Trade” the Prevalent Format

“Border trade”, or “petty trade in border areas”, is the principal form of trade in Xinjiang. In the wake of economic growth in the neighbouring Central Asian countries, many trading firms in Xinjiang are expanding their business in those markets through "border trade". Exports through "border trade" include cotton/textile products, agricultural products and processed foods, as well as consumer and industrial goods sourced from other provinces or produced in collaboration with manufacturers in these provinces for export to Central Asia through Xinjiang.

"Border trade" in Xinjiang refers to import/export trade conducted by enterprises registered in Xinjiang with the government's foreign trade/commerce authorities and thereby qualified to trade with enterprises or other trading organs in Xinjiang's “neighbouring” countries – that is, countries bordering on Xinjiang, via Xinjiang's designated land ports. “General trade” refers to import/export trade conducted by all countries through Xinjiang or other ports of China. In other words, enterprises with the relevant qualifications may conduct trade in the form of "border trade" when trading with neighbouring countries such as Kazakhstan but must conduct trade in the form of "general trade" when trading with non-neighbouring states.

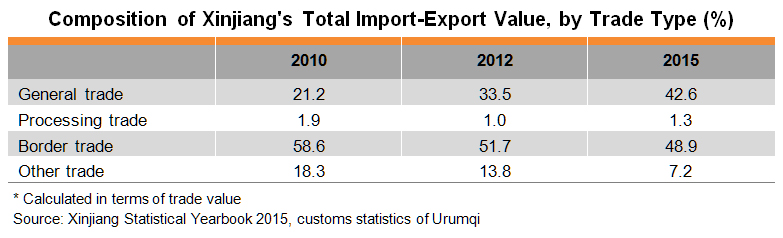

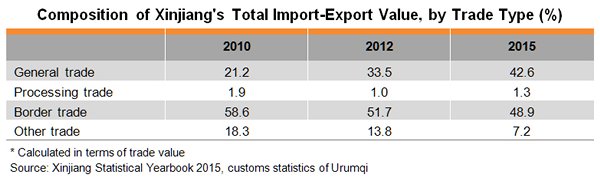

Although "border trade" still accounts for the lion's share of Xinjiang's import/export trade, as an official of Xinjiang's department of commerce pointed out, some of the preferential policies for border trade have been abolished and there is a movement in the direction of general trade. In fact, as can be seen from Xinjiang's import/export trade statistics, border trade dropped from 58.6% of total trade in 2010 to 48.9% in 2015, while general trade has soared from 21.2% in 2010 to 42.6% in 2015.

Shopping Malls as Trade Platforms

Geographically, Xinjiang borders a number of Central Asian countries. Culturally, Xinjiang’s Uyghur population and other minorities have similar customs and habits to people in Central Asia. Border inhabitants’ petty trade ties with neighbouring countries are long-established. Xinjiang's export companies are mainly found in Urumqi and border ports such as Yining and Khorgas, with Urumqi as their top choice.

Urumqi boasts a variety of wholesale markets, where traders from other provinces have set up shop. They attract merchandisers not just from Urumqi and other domestic markets in northwestern China but also others engaged in border trade between Xinjiang and Central Asia. Many of the shops in these markets are opened by merchants from Zhejiang province, for example. An operator of a wholesale market in Xinjiang estimates that over 100,000 people from Wenzhou, Zhejiang, are conducting business in these markets and that at one stage between 200,000 and 300,000 people from Wenzhou were to be found in Xinjiang, although that number has since fallen somewhat.

These wholesale markets deal in all kinds of goods. For example, Urumqi’s Bianjiang Hotel international trade city mainly deals in garments, shoes, headwear and other light industrial goods. The Diwang international mall, Dehui trade city and Huochetou foreign trade wholesale market mainly deal in garments, shoes, headwear and fashion accessories. The Xinjiang small commodity city sells furniture, bags/luggage and home appliances. Hualing comprehensive market mainly deals in building materials and furniture, while the Xiyu international trade city specialises in auto parts, tyres and automotive cosmetic products.

Some of these wholesale markets are very large. For example, the Hualing comprehensive market has three buildings and houses about 10,000 businesses from all over the country. Daily visitor traffic is said to average around 100,000 and the goods are sold to Urumqi's neighbouring prefectures and counties and even exported to neighbouring countries such as Kazakhstan.

The Xiyu international trade city resembles a small commodity city in Yiwu, Zhejiang province, and has about 1,000 shops, most of which deal in auto parts, tyres and automotive cosmetic products. They essentially act as agents and frequently participate in exhibitions to find suitable suppliers. They have their own warehouses, which they use to store popular merchandise sourced from the coastal areas to meet market demand at any given time, although they may also make purchases on receiving orders. The period from June to August tends to be their off season. Buyers from Central Asia can stay for any length of time, from just a few days to several months at a time. The market has hotel rooms/apartments to meet their accommodation needs and it is understood that between 400,000 and 500,000 visitors stay in the hotels each year. The trade city also boasts logistics service providers, dedicated logistics parks and supporting customs services.

Challenges Facing Xinjiang's Foreign Trade

After many years of growth, Xinjiang's exports to Central Asia started to fall as market demand in the region, and China's exports overall, dropped in 2015. Xinjiang's exports dropped 25.4% in 2015, with exports to Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan dropping by 40.1% and 21.2% respectively, although exports to Russia rose by 37.5%. Economic cycles and shifts were partly responsible for reduced market demand in Kazakhstan. The falling price of oil and other commodities in recent years has directly affected the performance of the Kazakh and other Central Asian economies. Substantial currency devaluation in these countries has also weakened their purchasing power. Overall, China’s exports to Kazakhstan saw a drop of 33.8% in 2015.

Xinjiang's exports to Central Asia also face a number of structural challenges. Firstly, the influence of the Russia-Belarus-Kazakhstan Customs Union has weakened the competitiveness of China's export goods. The unification of import tariffs between these three countries has led to an increase in tariffs on goods imported by Kazakhstan from China. The union also encourages trade between member states, which has had a detrimental effect on imports from China. The deal has also led Kazakhstan to gradually improve customs clearance management for some “grey” imports. Meanwhile, some buyers from Central Asia have started to make purchases directly from Yiwu, Zhejiang province, thus impacting on Xinjiang's intermediary role.

Still a Role For Xinjiang as Trade Intermediary

One local trader told HKTDC Research that while some buyers from Central Asia had gone directly to inland and coastal cities to make purchases, some claimed to have had bad experiences in doing so – for example, they found the quality of goods was not what they paid for. For this reason, many buyers still preferred to make purchases through trusted middlemen. Central Asian buyers may also encounter language problems when making direct purchases, while mainland suppliers may not be able to provide all the required customs clearance services (including customs clearance for Kazakhstan). Xinjiang's trading companies, on the other hand, are in a position to offer one-stop services.

As a trade intermediary, Xinjiang has also started to develop in terms of offering online platforms. For example, the Yema Group, a large trading company in Xinjiang, plans to start B2C cross-border e-commerce with Central Asia by sourcing goods from the mainland and selling them, through Urumqi, to consumer markets in Central Asia and Russia. The group will mainly target Russia, followed by Kyrgyzstan, because it has Russian language expertise and has established logistics and payment systems in those markets.

Hong Kong companies interested in venturing into Central Asia should look for opportunities via Xinjiang's trading firms and relevant e-commerce platforms. Many companies have set up production facilities in Xinjiang’s economic and technological development zones, bonded areas and export processing zones. There they are able to make use of raw materials and semi-finished materials produced both locally and in other parts of China, and of raw materials and spare parts imported from Central Asia and other countries, for production and processing in Xinjiang and, ultimately, export to Central Asian markets. Hong Kong companies may alternatively look to partner with existing operations in this area.

| Content provided by |

|

Editor's picks

Trending articles

ONE BELT ONE ROAD

By BDO Singapore

“This initiative will directly affect 4.4 billion people with a collective GDP of US$2 trillion once completed.”

The “One Belt One Road” (OBOR) initiative was announced by President Xi Jinping of China in 2013. This initiative was brought forth during his visits to Kazakhstan and Indonesia in 2013, when he formally announced the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road initiatives. This subsequently became a vital foreign policy for China in many aspects, mainly with the intention of promoting economic cooperation amongst countries along the “Belt” and “Road” routes.

Please click to read the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Can Exporting Industrial Capacity Rescue the Chinese Economy?

By China-United States Focus

In 2015, the Chinese government unveiled a new slogan – “industrial capacity cooperation” – as it pursued trade and investment deals abroad. At the time, the Chinese economy was headed for serious trouble, with manufacturing profits dropping and worrisome bubbles preparing to burst in domestic financial markets. In essence, China now seeks to export its excess industrial capacity as a means to cope with its economic troubles. On the one hand, this is a strong sign that China is becoming a mature industrial power, following in the footsteps of nations like the United Kingdom and the United States before it. Yet global economic conditions suggest that China may not be able to export its way out of the present crisis.

A country exports its industrial capacity when it invests industrial capital – factories, machinery, and so on – overseas. For example, a Chinese firm might open a factory in Ethiopia with its own money and machinery. We can tell that China is trying to export its excess capacity by examining the international deals and statements that the Chinese government has made over the past year. In May 2015, the Chinese government announced a $70 billion plan to export spare capacity from industries including railway construction and telecommunications technology. Officials and state news agencies heralded the new plan during a Latin American tour that included stops in Brazil, Chile, Peru, and Colombia. Further ventures were announced throughout the year in countries as far apart as Ethiopia and Kazakhstan. Recently, China signed a memorandum of understanding with Saudi Arabia pledging to jointly pursue China’s One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative, including industrial capacity co-operation.

The industries China has highlighted as key priorities for its industrial capacity co-operation initiatives are those that suffer from chronic overcapacity problems: steel, construction materials, electrical power infrastructure, and rail manufacturing. During its economic rise in recent decades, China became the globe’s preeminent manufacturer of many of these industrial commodities. Now, global demand simply cannot keep up with China’s capacity to produce goods like steel, leading to a steep decline in prices. By exporting excess industrial capacity that simply cannot profitably produce in domestic conditions, China may hope to relieve some of the pressure on its industries.

Of course, investing capital abroad will help China increase its international influence. Exporting industrial capacity is a key component of Chinese initiatives like OBOR and the new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and most countries are more than happy to welcome Chinese investment. If Chinese construction equipment cannot be put to use in China, it can be used in Central Asia to develop infrastructure that will open markets to Chinese goods and allow further penetration of local economies.

Exporting both excess commodities and industrial capital is a classic strategy that developed economies use to cope with saturated markets and diminished opportunities for investment at home. Lenin famously argued that the struggle to export excess capacity motivated imperialism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Both the United Kingdom and the United States followed this path as they rose to global prominence, becoming creditor nations that dispensed industrial and financial capital around the world. Where economic power led, political influence often followed; where capital could not enter on its own, armed force opened the way.

Given these historical precedents, China’s transformation into a capital-exporting economy suggests that it is maturing as an industrial power and that its international influence will continue to expand. China and today’s United States occupy remarkably similar positions to yesteryear’s United Kingdom and a rising United States in the early 20th century, albeit with some notable differences. Foreign investment is still extremely asymmetric, with developed nations far outspending their developing counterparts. From 1980 to 2008, the foreign direct investment of firms from the advanced capitalist economies (the U.S., Europe, and Japan) grew from $500 billion to nearly $14 trillion. By the end of this period, the foreign employment and sales of these companies exceeded their domestic numbers. Firms from developing countries also increased their foreign investments, but these totaled up to less than a fifth of the advanced countries’ investments. The Netherlands, a country of only 16 million people, had more investments abroad than Brazil, Russia, India, and China combined.

Despite its implications for China’s international power and prestige, there is good reason to be skeptical that exporting excess capacity will rescue the Chinese economy in the short term. As I have written in earlier articles, today’s economic troubles reflect unique structural conditions that are unlikely to disappear without some kind of major destruction and devaluation of global capital.

The problem is that China is trying to export its way out a local crisis caused in large part by a global glut of commodities. Moving excess industrial capacity abroad will do little to alleviate the fact that the global supply of many key goods is now far in excess of demand unless those local markets happen to be heavily protected from international dynamics. Given that countries like Brazil, a key Chinese partner, are also experiencing collapsing prices, it is hard to believe that there are many suitable outlets for this strategy. Put simply: Building Chinese-owned factories in Brazil may not be particularly profitable if no one buys what they produce.

Like its historical peers, China is starting to mature as an economic powerhouse. However, it is coming of age in a time of severe economic turbulence and uncertainty. It remains to be seen how China’s rise will be impacted by the difficult conditions of the present day. Whatever the case, we should expect Chinese foreign investment to continue to grow, spurring a commensurate rise in its political influence.

Please click to read the full article on the website of China-United States Focus.