Chinese Mainland

Kazakhstan: A Modern Silk Road Partner

As the most advanced economy in Central Asia, oil-rich Kazakhstan leads the region in terms of GDP and purchasing power, while also acting as a key business and logistic hub linking China and Europe. This was the message of President Xi Jinping’s speech at Nazarbayev University in Astana on 7 September 2013, when he first outlined the proposed Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Kazakhstan has since become an important component in the BRI. This has seen it strive to further upgrade and modernise its logistics and trade infrastructure, including working to develop the Khorgas-East Gate Special Economic Zone in order to accommodate increased levels of Sino-European trade, logistics and investment. As the host of Expo 2017, the first World’s Fair in Central Asia, and the newest WTO member (as of 30 November 2015), Kazakhstan is seen as having huge potential, especially if it succeeds in its ambitious upgrade to its global connectivity.

The Genesis of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)

Since its announcement by President Xi Jinping in September 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has become an integral part of Sino-Central Asian development. Kazakhstan, as a regional powerhouse in Central Asia and a crucial logistics link between China (the world’s largest industrial producer), and Europe (the world’s largest consumer market) is seen as playing a key role in the successful development of the BRI. In particular, two of the six international economic co-operation corridors set to be developed and/or strengthened under the BRI will pass through Kazakhstan, before branching out to the ports of West Europe, the Mediterranean coast and the Arabian Peninsula.

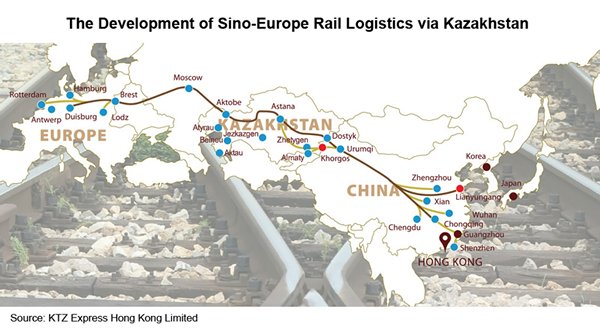

In conjunction with the BRI developments, the new Eurasia Land Bridge (also known as the Second Eurasia Land Bridge) is an international railway line running from Lianyungang in China’s Jiangsu province through Alashankou (one of the major border crossings between China and Kazakhstan) in Xinjiang, to Rotterdam in the Netherlands via Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, Poland and Germany. Capitalising on the New Eurasia Land Bridge, China has opened an international freight rail route linking Chongqing to Duisburg (Germany); a direct freight train running between Wuhan and Mělník and Pardubice (Czech Republic); a freight rail route from Chengdu to Lodz (Poland); and a freight rail route from Zhengzhou to Hamburg (Germany). All of these new rail routes offer rail-to-rail freight transport, as well as the convenience of “one declaration, one inspection, one cargo release” for any Europe-bound cargo transported from China or wider Asia.

Meanwhile, the China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor (running from Xinjiang in China and joining the railway networks in Kazakhstan after exiting China via Alashankou) is regarded as a highly ambitious and important step in enhancing the connectivity of landlocked Central Asia. It will link with markets in Iran and Turkey in West Asia, but also with the Persian Gulf, the Mediterranean coast and the Arabian Peninsula. This represents a breakthrough for the landlocked countries in Central Asia – including Kazakhstan, the world’s biggest landlocked nation – and gives them access to the worldwide ocean logistics business and making them key players in the global multimodal logistic chain.

Kazakhstan is striving to paint an optimistic picture of its role as a logistic/cargo transit hub with the announcement of a number of major projects. These include new rail connections in inner regions of Kazakhstan, such as the 293 km-long Zhetygen line (near Almaty)Khorgas[1], which reduces the route from China to the port of Aktau on the banks of the Caspian Sea to 500 km. There is also the 988 km-long Jezkazgan-Beineu line, located in Central Kazakhstan, that cuts the transit through Kazakhstan to 1,000 km. Combined with the 400 km-long highway between Aktau and Beineu and the expansion of the port of Aktau to handle cargo flows up to 25 million tonnes per year on the Caspian coast, Kazakhstan is now set to connect more readily with such countries as Azerbaijan and Iran. The country is also an emerging production base for those Asian manufacturers (mainly Chinese, Japanese and Korean) targeting the European market.

By either going through the freight rail route linking Chongqing to Duisburg (the so-called Yuxinou railway) or the Caspian Transit Corridor (passing through Kazakhstan, Caspian Sea, the Baku (Azerbaijan) – Tbilisi (Georgia) – Kars (Turkey) railway and the Marmara Tunnel (Turkey)), the distance travelled is halved to 8,500 km, compared to the 20,000 km length of the sea routes. Transit time can be thus reduced from 45-50 days by sea (via the Suez Canal) to about two weeks. As the land or land-plus-Caspian Sea options, though, can easily cost 80-100% more than sea shipping, the land and land-plus-Caspian Sea routes remain attractive, largely to cargo that is not too urgent to ship by air, but time sensitive enough to not go by sea.

To make the land routes competitive and attractive to traders used to ocean freight, further operational progress is required. Kazakhstan, for example, currently uses a rail gauge dating back to the Soviet era and this is 85mm broader than the international standard gauge used in most of Europe and China. The necessary change of gauges at the Chinese-Kazakh border and Belarusian-Polish border can be time-consuming, while lengthy document authentication procedures and annoying bureaucracy at border crossings in Central Asia can also be a major inconvenience for traders.

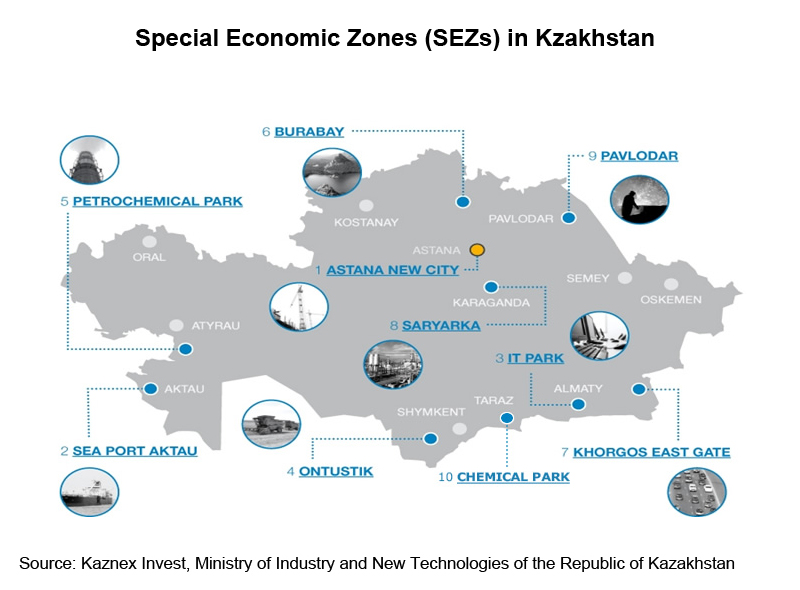

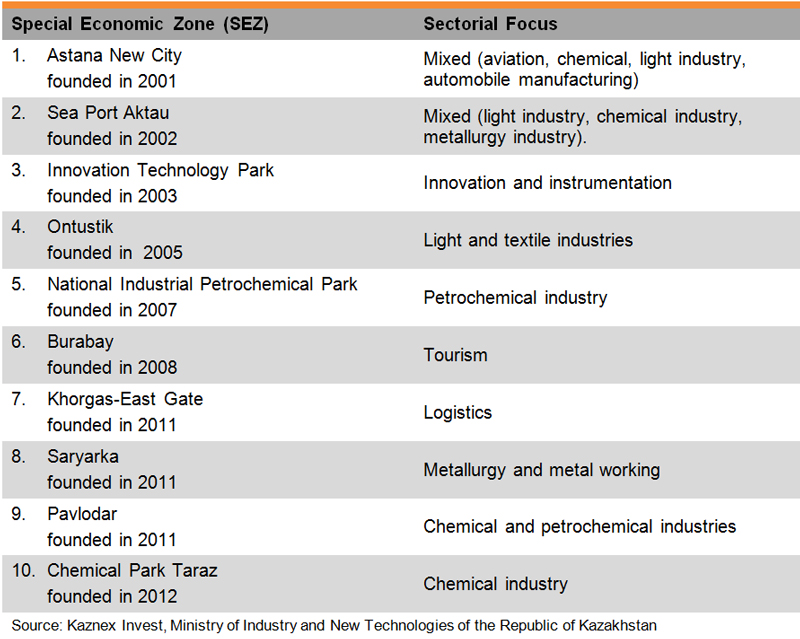

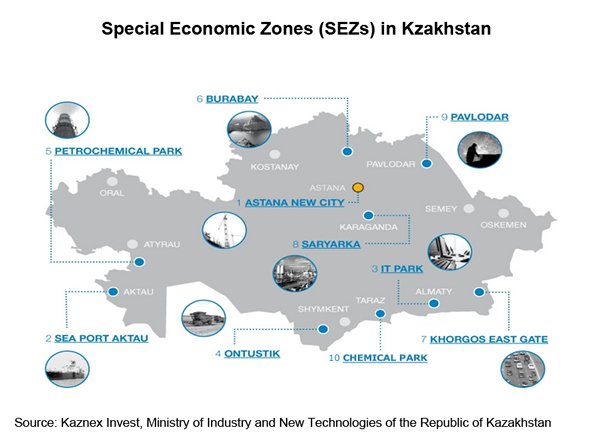

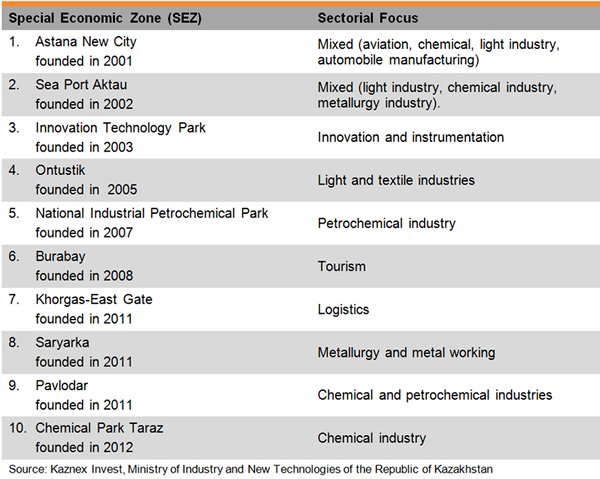

To better complement the expected increase in cargo traffic passing through the new Eurasia land bridge, 10 special economic zones (SEZs), all with different sectorial foci and priority activities, are being founded and/or further developed across Kazakhstan, including the US$3.5-billion Khorgas-East Gate SEZ near the Chinese-Kazakh border. Kazakhstan is also keen to invest on the Chinese mainland and in Hong Kong in order to expand its reach into Asia and gain the benefits likely to accrue from being an early supporter of the BRI.

The Khorgas-East Gate SEZ, located on the border between China and Kazakhstan, has fast become one of the anchor projects for transforming Kazakhstan into a major commercial and transportation hub for the Eurasian continent. The SEZ has several advantageous facilities, including the International Center for Boundary Cooperation (ICBC), a dry port, logistics and industrial zones, ready connection with the Zhetygen-Khorgas Railway and West Europe-West China Highway, the possibility of direct access to the port of Aktau and a package of attractive fiscal benefits, including exemption from import tariffs, land tax, property tax and value-added tax.

Taking advantage of Hong Kong’s singular role as a “superconnector”, one ready to deliver game changing solutions for the 60plus countries along the Belt and Road, KTZ Express, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Kazakhstan Railways, opened its international development office in the city. It aims to build a platform to promote multimodal freight logistics between Europe and China, via Kazakhstan, including the launch of new rail freight services from Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Wuhan and Xian to Europe via Kazakhstan. In a bid to further expand its reach into Asia, KTZ Express has also invested in a 21-hectare intermodal freight and logistics centre at the port of Lianyungang in China’s Jiangsu province. This is intended to provide direct access to Central Asia for cargo coming from Japan, Korea and Southeast Asia.

The Futuristic Look of the Old and New Capitals of Kazakhstan

From 1936 till 1997, Almaty, the largest city in Kazakhstan, was the nation’s political, business, financial and logistics capital. With a population of some 1.6 million people (2015), the city’s strength as a Central Asian logistics and distribution hub has been fostered in line with the BRI and the related infrastructure, such as the nearby Khorgas-East Gate SEZ. Its role as the country’s business and financial centre, however, is subject to challenge. The Kazakh government now plans move the head office of the central bank to Astana[2], the official capital of Kazakhstan since December 1997, in order to ensure close cooperation with the government and other public bodies. It is also now encouraging other banks, financial institutions and multinational companies to relocate their headquarters to the new capital.

Home to about 850,000 people, Astana, the new capital, is a planned city and full of futuristic buildings, retail facilities and mega projects. Astana is turning itself into a regional business and financial hub, a commitment underlined by its growing number of flagship buildings. The city is also home to the world’s biggest tensile structure – the Khan Shatyr Entertainment Centre – a shopping and entertainment complex opened in 2010. The tallest building in Central Asia, an 88-storey tower, is also currently under construction. This will form part of the US$1.6-billion Abu Dhabi Plaza Complex, as well as the site for Expo 2017 Venue. This will be turned into an “international financial hub” after the event. The complex is subject to common law and uses English as its official language.

Under the theme of “Future Energy”, Kazakhstan is the first former Soviet state to host a global trade event of the scale of Expo 2017. The event is expected to attract exhibitors from more than 100 countries and receive two to three million visitors between June and September 2017. Thanks to the concentration of many striking new buildings and tourist attractions, as well as the expansion of the “Official Air Carrier of EXPO-2017”, Air Astana (Kazakhstan’s largest airlines), Astana is also looking to establish itself as a regional hotspot for tourism and the MICE (meetings, incentives, conferences and exhibitions) industry.

Source: Mabetex Group

Other Visionary Trade-facilitating Developments

Aside from being a strategically important player under the BRI, as well as a founding member of the Asia Infrastructure Investment bank (AIIB), Kazakhstan is also committed to creating a more business-friendly environment, while also nurturing its longer term economic prospects. Its AIIB membership is particularly important, given that the institution is expected to play a pivotal role in supporting the development of infrastructure and other sectors along the Belt and Road routes.

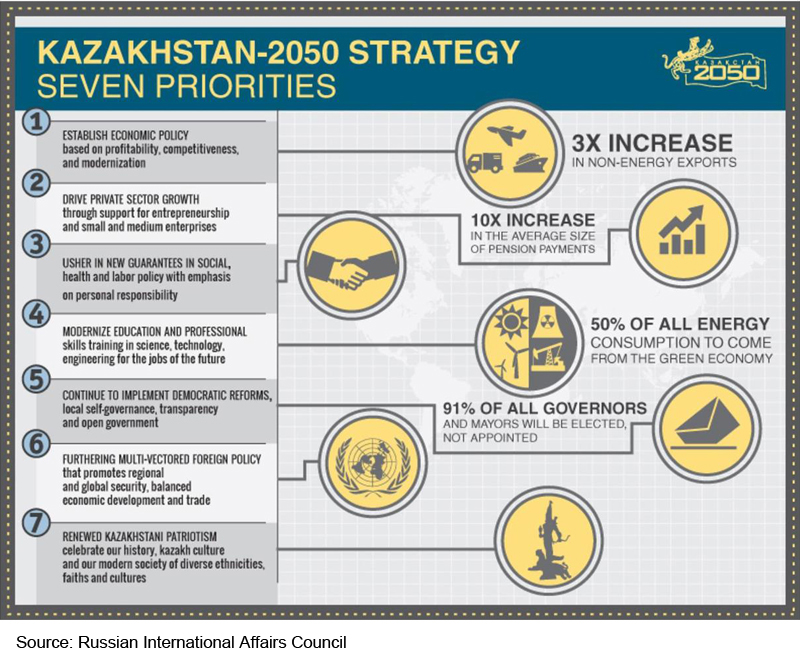

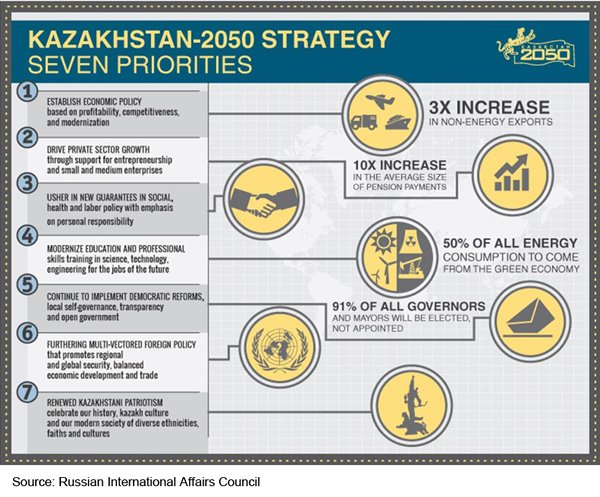

In tandem with this new strategy for Kazakhstan’s development through to 2050, many economic reforms have been introduced to speed up the nation’s shift away from its dependence on its trade in raw materials. This has seen it look to nurture its high-value-added industries in a bid to overcome volatility in global energy prices and create a stronger, more balanced base for economic growth. These moves were outlined by the Kazakh President, Nursultan Nazarbayev in his state-of-the-nation address on the Kazakhstan 2050 Strategy in December 2012 and also formed part of the new economic plan, Path to the Future, announced in November 2014.

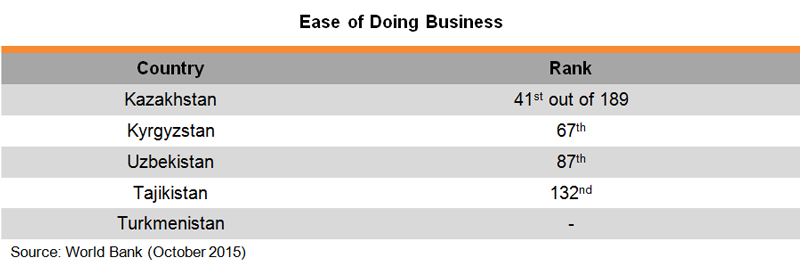

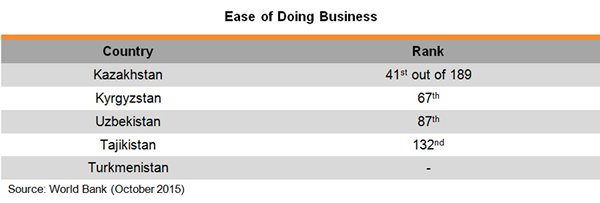

Kazakhstan has already streamlined many of its internal procedures, resulting in reduced time being required to register a business, while seeing less paperwork required for customs procedures and other business operations. Its ultimate goal, within the next decade, is to become one of the top-30 countries in the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index (GCI)[3] and the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business rating.

This, together with the five institutional reforms set out in the 100 Steps Program, unveiled in May 2015, is aimed at creating a modern and professional civil service, with high transparency and accountability. It is also designed to bolster the country’s on-going privatisation project, which began with the launch of 60 companies in October 2015. Taken together, these initiatives show how keen the country is to become a business-friendly destination for foreign investment.

Last year, Kazakhstan was named Central Asia champion in recognition of its improvements to its business environment. This was thanks to its large number of regulatory reforms, such as its fast track, simplified procedures for handling small claims. These reforms were implemented in the year from 1 June 2014 to 1 June 2015, with seven of them documented by the World Bank.

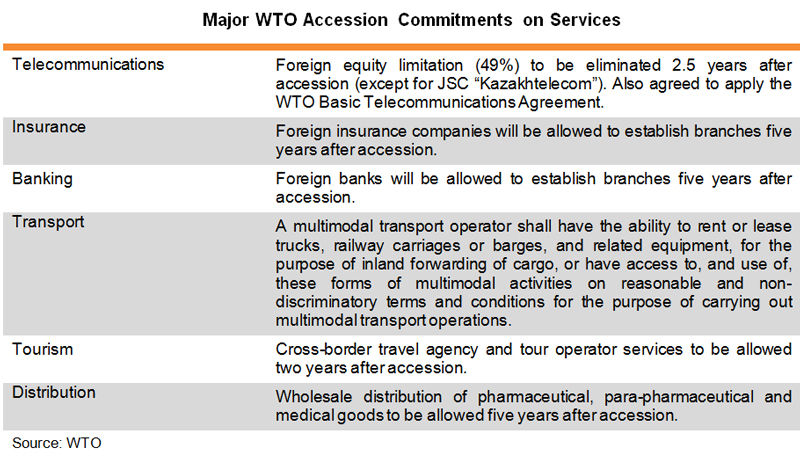

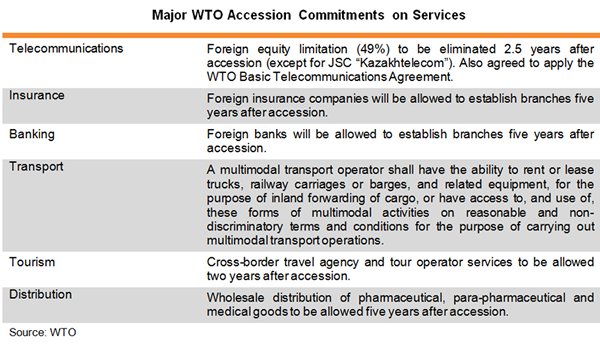

In order to overcome the economic handicaps of being a landlocked country, Kazakhstan is committed to boosting its connectivity with its neighbours and further integrating itself with the global economy. After 20 years of negotiation, Kazakhstan was officially accepted as the 162nd World Trade Organisation member on 30 November 2015. Not only will WTO accession limit the country’s average tariffs on goods to 6.1% (tariffs on agricultural imports would be limited to an average of 7.6% and non-agricultural goods to 5.9%) from 8.6% in 2014, but it will also remove the 49% foreign equity cap on foreign investment in the telecommunications sector. The branching limitation on foreign banks and insurance companies will also be lifted over the coming five years.

In addition to WTO accession, Kazakhstan is a founding member of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU[4]). As an expanding regional economic integrator, which currently includes Russia, Belarus, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan, the EAEU can also be seen as a potentially effective business shortcut for foreign traders looking to access the 290 million-strong CIS market and those countries that are still outside the WTO, notably Azerbaijan, Belarus and Uzbekistan.

Kazakhstan as a Modern Silk Road Partner

Kazakhstan, with an average of just 16 people per square mile, is one of the most sparsely populated countries in the world. This, together with its large land area – the world’s ninth-largest – and relatively small population (less than 18 million in 2015), makes it suitable to function as a regional distribution platform, rather than as a large, standalone consumer market.

The country switched to a floating exchange rate on 20 August 2015 in order to boost its competitiveness. In tandem with the currency depreciation of Russia and China, its major trading partners, and the drop in international oil prices, this triggered a sharp 50%-plus depreciation for the Kazakh Tenge (the local currency). This may have also dampened the country’s import appetite over the short term and made it more of a conduit for trade.

While its energy and metallurgy sectors remain key attractions for foreign investors, Kazakhstan’s industrial diversification and upgrading from a raw materials supplier to a service-based economy will offer Hong Kong companies good opportunities across a range of sectors, including logistics, trading and marketing.

Kazakhstan is the only Central Asian country (CAC) with a consulate office in Hong Kong. This, together with a reciprocal 14-day visa-free arrangement for HKSAR and Kazakh passport holders, makes business connections between the two economies far easier than those with other CACs. In addition, direct flights between Hong Kong and Almaty give the country a further advantage over other CACs in terms of being Hong Kong’s first port of call in Central Asia. The flights are available twice a week (on Tuesday and Friday).

Taking advantage of this growing momentum, a number of Kazakh companies, such as Kazakhmys PLC, a leading natural resource group, are either listed or considering listing in Hong Kong. In a similar move, KTZ Express, a subsidiary of Kazakhstan Railways, opened a Hong Kong office in 2014. A number of Kazakh SMEs have also chosen Hong Kong as their regional base in order to service the wider Asian market. This trend is poised to continue as Kazakhstan further liberalises and enhances its trade and business infrastructure, while enhancing its connections with the rest of Asia as part of the BRI.

With stronger trade and investment expected to flow in and out of Kazakhstan in the post-WTO era and Sino-Kazakh economic cooperation growing and diversifying in conjunction with the BRI, Kazakhstan will provide a wealth of opportunities for Hong Kong companies. These will be particularly apparent in such sectors as infrastructure, real estate services (IRES), logistics and financial services. Meanwhile, Kazakhstan, given its fast-improving business environment, is proving increasingly attractive to those Hong Kong businesspeople wanting to access the largely uncharted Central Asian market, particularly those countries allied along the modern Silk Road.

[1] China’s youngest city, Khorgas was officially established on 26 June 2014. It has become one of the busiest border crossings between China and Kazakhstan.

[2] The city was originally named Akmola when it became the capital of Kazakhstan in 1997. It was consequently renamed Astana in 1998.

[3] Kazakhstan was ranked 42nd in the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index 2015-2016 (published in September 2015).

[4] EAEU is an international organisation established to pursue regional economic integration. It acts to facilitate the free movement of goods, services, capital and labor, while pursuing a coordinated, harmonised and unified policy in sectors determined within the Union. Current member states include Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Russia.

| Content provided by |

|

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Hong Kong Maritime Services Cluster: Meeting the Challenges

A Difficult Time for the Global Shipping Industry

The global shipping industry has struggled since the 2008 financial crisis due to soft demand and overcapacity. With the rare exception of increased transportation of LPG on the back of strong GDP growth in India and some Southeast Asian economies in 2015, the softer Chinese economy and falling commodity prices more than offset the positive blip and continue to cast a negative outlook over the industry, with ship owners of most vessel types finding it hard to see any bright spots in 2016.

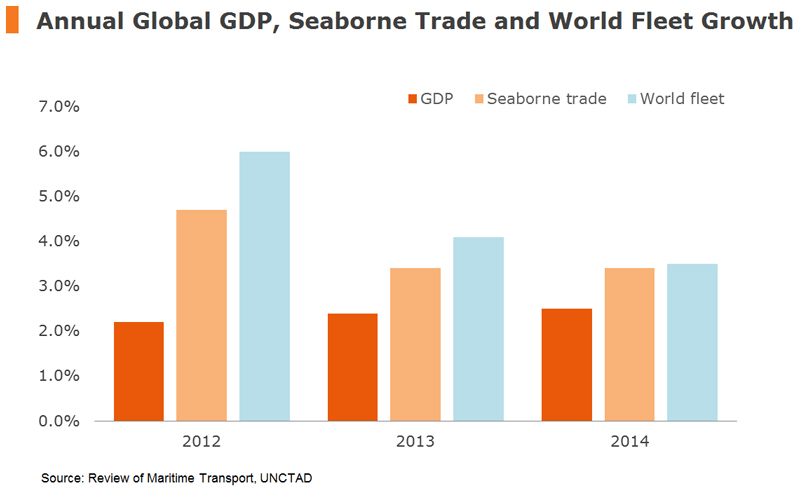

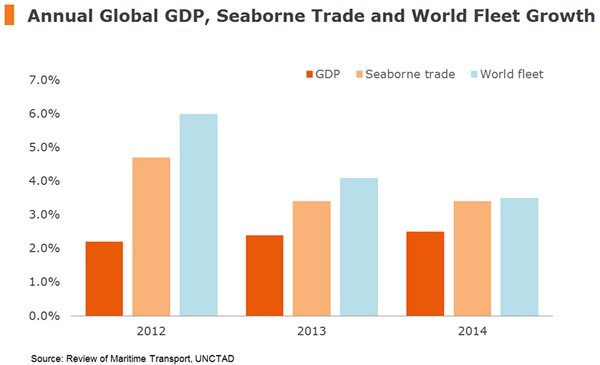

It has been reported in recent months that many ship owners have continued to place orders for large-sized vessels despite a weak trade outlook, apparently in an effort to reduce operational cost at the margin by achieving better economies of scale. According to the latest Review of Maritime Transport issued by UNCTAD in October 2015, growth of the world fleet in deadweight tonnage (DWT) outpaced that of global GDP and seaborne trade in the period of 2012-2014. As the figure below shows, the global economy and seaborne trade grew at an annual average of 2.4% and 3.8%, respectively, during that period, while the size of the world fleet expanded by a larger magnitude of 4.5%.

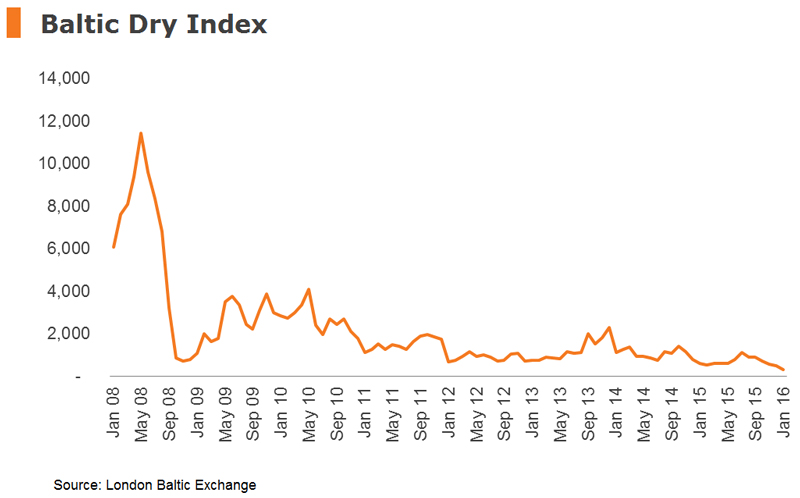

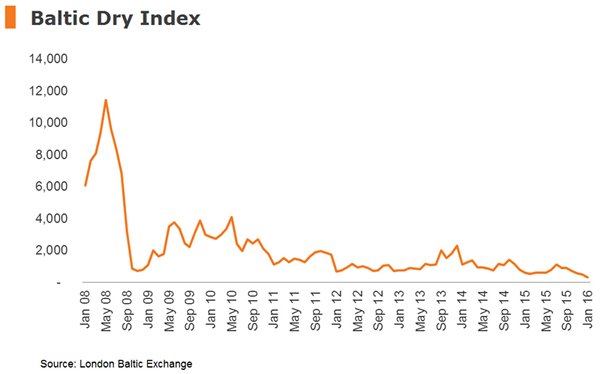

According to Clarksons Research, the world fleet is estimated to have reached 1.8 billion DWT in 2015, translating to a year-on-year (YOY) growth of 3%, equal to the projected global GDP growth, but slightly ahead of the seaborne trade growth rate of 2% for the same year. For the container segment alone, it was estimated that new capacity of almost 1.6 million TEUs was added in 2015, a time when more than one million TEUs of idled container capacity had already been reported. Against the background of such supply-demand imbalance, the Baltic Dry Index (BDI), a key industry tracker of the daily earnings of ships carrying dry commodities such as metals and grains, plunged to a record low (of 317) in January 2016, more than 95% below its 2008 peak.

The Baltic and International Maritime Council (BIMCO) has warned the shipping industry to brace itself for a challenging 2016 amid subdued global trade growth and an economic slowdown in emerging markets – including China, the world’s “factory” and largest exporter. Amid weak demand, shipping-freight rates are likely to remain depressed prior to further supply-side adjustment and market consolidation to alleviate the market imbalance, in particular through more careful management of deployed capacity, placement of new orders and the scrapping of old vessels.

A Growing Hong Kong Shipping Community Despite the Global Downturn

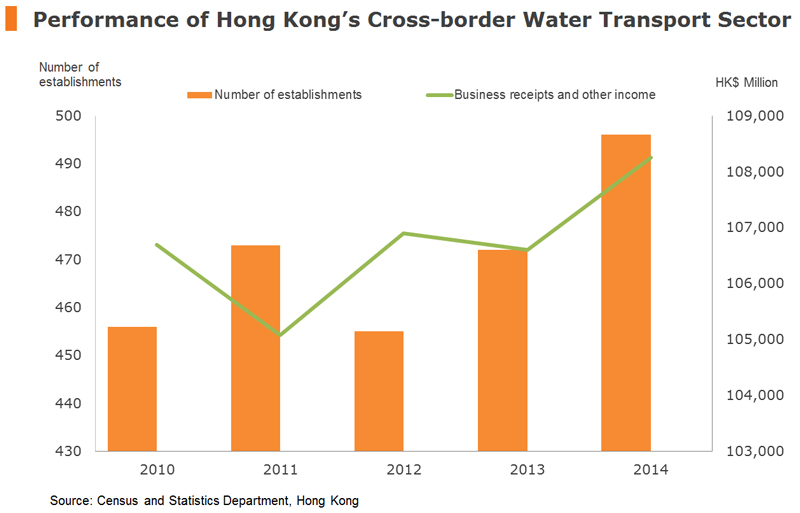

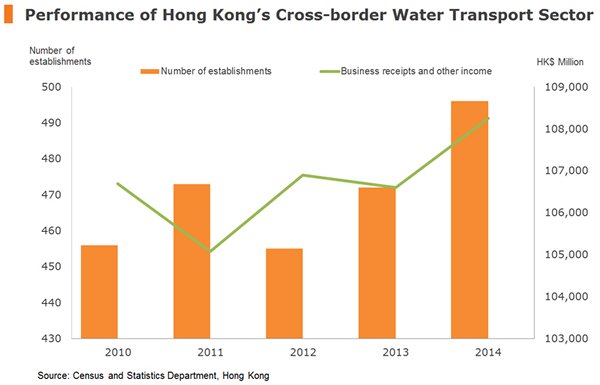

Given the unfavourable external environment, perhaps the only encouraging development for Hong Kong’s shipping community is that the industry has performed relatively well over the past few years, showing great resilience despite the precipitous fall in freight rates. Based on the latest data released in November 2015, the number of business establishments in Hong Kong’s cross-border water transport industry[1] increased by 8.8% between 2010 and 2014, to 496 from 456, while business receipts during the same period also rose to HK$108.3 billion, 1.5% above its 2010 level.

Hong Kong’s shipping industry, as represented by the cross-border water transport establishment, managed to register income growth in 2014 and enjoyed a much stronger performance than that indicated by general freight rates with the BDI as a proxy, which showed a YOY fall of more than 70%. This was also borne out to an extent by the positive equity price performances of Hong Kong-listed shipping companies in that year[2]. There could be a host of reasons behind the relatively stronger performance of Hong Kong’s shipping companies. Among other things, Asian economies were more robust in 2014 than those in Europe and the Americas, thereby generating stronger demand for intra-regional freight transportation, while extra-regional freight traffic was at a lower ebb.

The global shipping industry has continued to suffer from the overhang of multi-year adjustment since the 2008 financial crisis, and is now grappling with the additional challenges of a global economic slowdown aggravated by a stuttering Chinese economy, as well as the lingering problem of vessel overcapacity. While the short-term outlook shows few bright spots, the long-term view is more positive with seaborne trade expected to double by 2030, although industry consolidation and the attendant adjustment over the medium-term is likely to be difficult.

Hong Kong: A Vibrant Maritime Services Centre

Certainly, the performance of Hong Kong’s shipping industry has a strong bearing on the performance of other strands of maritime services, such as shipping insurance, finance, broking and legal services. The performance of individual segments of Hong Kong’s maritime service cluster can at best be examined by a very limited pool of available official statistics, particularly in relation to business receipts. [3] For example, no official statistics are available for business receipts of Hong Kong’s ship insurers. However, official figures released in September 2015 show that the number of authorised ship insurers in Hong Kong increased by two, to 86, in the period 2013 to 2014. More remarkably, gross shipping insurance premiums went up by 18% to HK$2.36 billion in 2014, followed by a YOY increase of 6% in the first six months of 2015.

As an international maritime centre (IMC), Hong Kong needs to reinforce its offerings in the face of growing regional competition and challenges due to the economic downturn. Hong Kong has always thrived as a leading IMC in Asia, thanks in no small measure to its rich maritime history and a large pool of ship owners and operators. As a pre-eminent port since the 1970s, the city has gradually expanded to emerge as an all-encompassing IMC, offering a comprehensive range of high-value-added maritime services including ship management, ship broking, shipping insurance, finance and legal services, along with the traditional port and shipping businesses.

The sections below will examine the long-term fundamentals that will play in Hong Kong’s favour, allowing it to seize fresh business opportunities arising from global industry consolidation, regional economic integration, as well as China’s attempt to foster stronger international cooperation through the Belt and Road Initiative, and the country’s economic strategy to rebalance its economy.

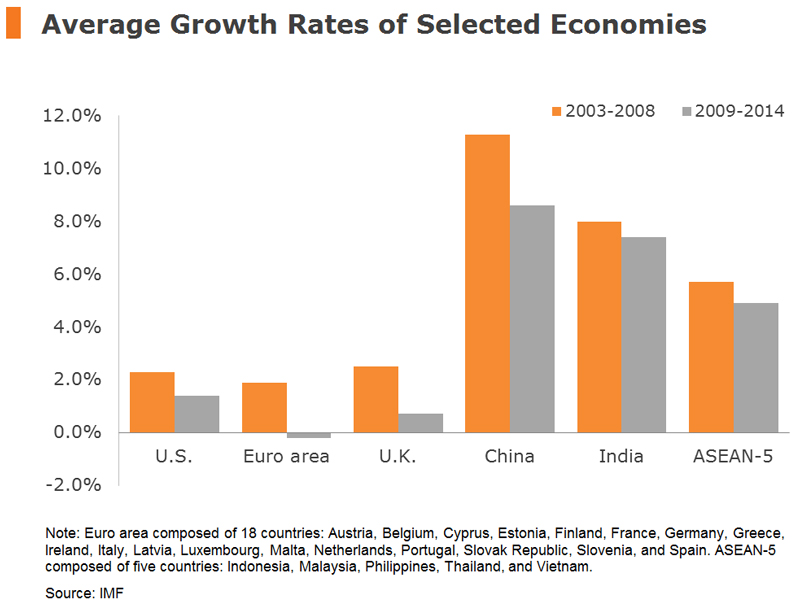

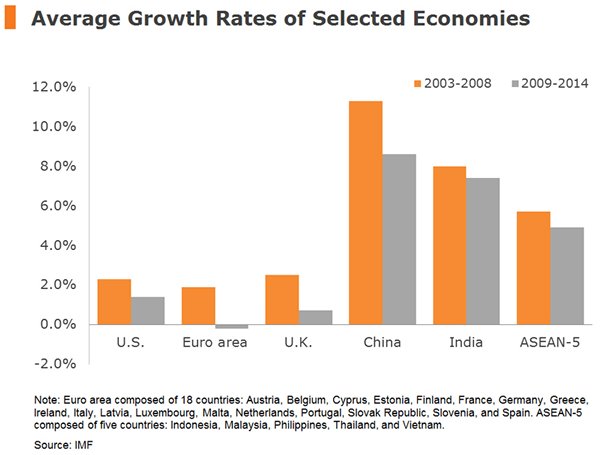

Shift of economic gravity and maritime power from West to East

It has become apparent that economic gravity has shifted from the West to the East in the past decade or so, and more profoundly since the outbreak of the 2008 financial crisis. In the intervening years, China has overtaken Japan to become the world’s second-largest economy, and displaced the US as the largest exporter and trading nation. Although China’s GDP growth fell to a 25 year low of 6.9% in 2015, one should not overlook the fact that the Chinese economy last year was 75% bigger than in 2008 in terms of real GDP. It would be a daunting task for a major developing economy such as China to keep sprinting at a neck-breaking pace while the rest of the global economy is experiencing uneven growth, with some nations recovering faster than others but a number of them striving to prevent a return to recession.

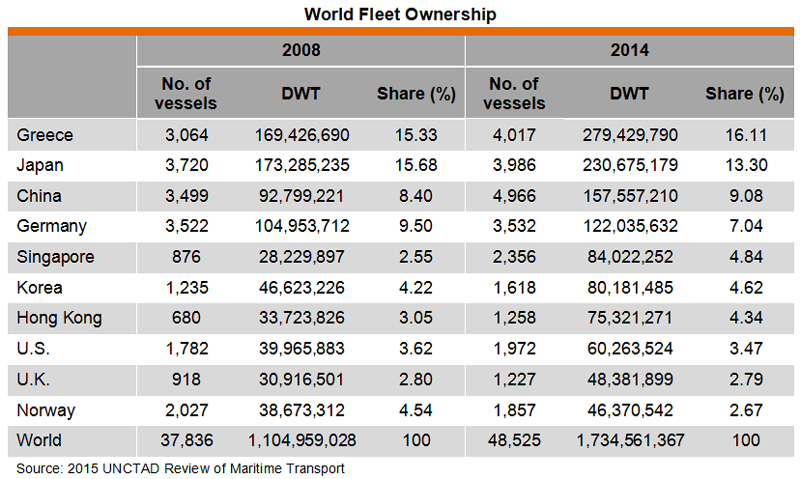

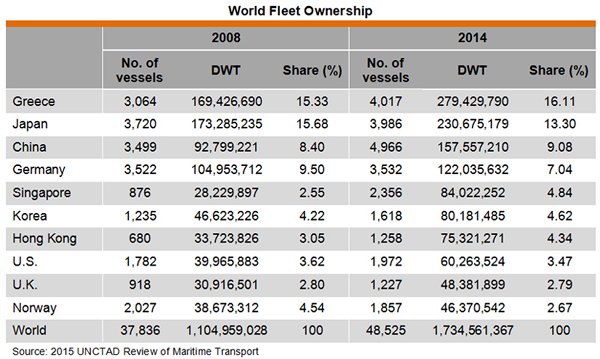

Asian economies have been rapidly expanding their presence in the international maritime community, according to world fleet ownership statistics, and it’s a trend that is expected to continue despite the ongoing global economic downturn. In 2014, half of the top 10 ship-owning territories were in Asia, accounting for 36% of the world’s total tonnage. By comparison, the top four European territories accounted for 29%.

Back in 2008, Europe dominated the sea, with five territories in the top 10, representing 35% of the world’s total fleet in terms of DWT. Another 31% was controlled by four Asian territories. In terms of DWT growth, Asian territories out-performed the world growth average of 57% in the period of 2008-2014. Among Asia’s top ship owning territories, Singapore showed the strongest growth (198%), followed by Hong Kong (123%), Korea (72%) and the Chinese mainland (70%). In terms of ship registration, Hong Kong was ranked fourth globally in 2014, accounting for 8.6% of the total tonnage.

Increasing regional opportunities

Before the 2008 global financial crisis, there was a prevalent view that world trade growth had been expanding at about twice the pace of world GDP growth. This trade-to-GDP relationship seems to have broken down over the past few years, with a slowdown in growth of world trade to just above that of world GDP growth, while both are eclipsed by world fleet growth. Nevertheless, increased regional attempts for further economic integration are expected to provide additional impetus to intra-Asia trade. According to the Asian Region Integration Centre, intra-Asian trade accounted for 55.6% [4] of the region’s total trade in 2014, up from 45.5% in 1990, and is expected to further expand, taking into account in particular the formation of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) in December 2015.

The AEC, with more than 600 million people, is envisioned to be a single market and production base, characterised by the free flow of goods, services, and investments, as well as a freer flow of capital and skills. At sub-regional level, the AEC is expected to boost intra-ASEAN trade to 30% of total trade in 2020, from about 25% in 2014. On the other hand, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), formally signed on 4 February 2016, creates the world's biggest free-trade area by bringing together 12 Pacific Rim countries [5] and is conducive to Asia’s extra regional trade. According to the World Bank, TPP economies account for about 36% of the world’s GDP and 25% of global trade, with the deal expected to lift trade of TPP members by 11 percentage points by 2030.

All these developments, along with the increased presence of ship owners in Asia, are expected to promote trade and help alleviate the demand-supply imbalance of freight vessels over the longer term, while also creating the incentives for maritime service providers to be clustered in the region. Despite the rough short-term environment, the annual volume of world seaborne trade is expected to increase to 20 billion tonnes by 2030, from 9.8 billion tonnes in 2014, based on projections by Lloyd’s Register. Trade routes connecting intra-Far East, Oceania and the Far East, the Far East and Latin America, and the Far East and the Middle East are seen as the drivers and point to the huge potential of Asia’s shipping industry.

Hong Kong’s IMC to Embrace Competition and Seize Opportunities

With world trade growing only slightly faster than world GDP, competition in freight transportation and shore-based logistics activities can only get stronger. As mentioned above, orders for bigger vessels and container ships are still being placed in a bid to achieve greater economies of scale amid the global economic downturn. Apart from meeting the challenges from competition in terminal, freight transportation and related logistics activities, there is an increasing recognition that Hong Kong needs to further enhance its appeal as a maritime services centre in Asia.

Hong Kong’s strong fundamentals and the London lesson

Undoubtedly, many overseas maritime companies set up their businesses in Hong Kong because of the city’s great location, comprehensive logistics network and huge pool of maritime-related service providers. Take the financial sector as an example. Hong Kong is an international financial hub with one of the most active capital markets and the world’s largest offshore RMB market. It has the expertise and the connections to serve as a stronger maritime finance centre in Asia by offering fundraising and myriad financial services.

The Hong Kong government has repeatedly noted that the city needs to reinforce the maritime services cluster and develop high-value-added maritime services, building on the strengths of its existing terminal business. In particular, there is a strong emphasis on emulating the success of London and specialising further in high-value, desk-based activities, which are seen as the drivers fuelling the continual growth and development of the city’s shipping industry over the longer term.

In London’s case, physical activities have long migrated to other parts of the country. However, the city remains one of the world’s most important maritime services centres with an impressive cluster of ship brokerage, insurance, finance and arbitration services due to its rich maritime history and skilled labour base. For example, the city accounts for approximately a quarter of global maritime insurance, and it is reported that British firms are responsible for arranging 30 40% of the world’s dry-bulk chartering contracts.

In the 2016 Policy Address, the Hong Kong government reiterated its commitment to strengthen Hong Kong’s role as an international maritime services hub in Asia. Among other things, a new Hong Kong Maritime and Port Board (HKMPB) will be formed by merging the existing Maritime Industry Council and the Port Development Council. This will aim to better develop a high-value added maritime services cluster through promoting manpower development, marketing and research on all fronts, while formulating strategies to enhance Hong Kong’s status as an international transportation centre.

Apart from the city’s free-port status, Hong Kong has adopted measures to improve its tax regime. As of December 2015, Hong Kong had entered into double taxation avoidance arrangements (DTAAs) specifically related to shipping income with 40 of its major trading partners. It is now actively looking to establish similar arrangements with its remaining trading partners.

In terms of human capital investment, the HK$100 million Maritime and Aviation Training Fund (MATF) was launched in 2014 to support a number of training and incentive schemes. This funding programme will provide support to young people or in-service practitioners to undertake relevant training courses and pursue professional studies, enhancing the overall competency and professionalism of the maritime industry in the medium to long term.

Hong Kong’s favourable business environment is further enhanced under the latest CEPA agreement signed between Mainland China and Hong Kong, which will allow basic liberalisation of trade in services between the two from June 2016, thereby opening the door for Hong Kong maritime services providers to fully tap into Mainland China.

The Belt and Road opportunities

At a time of a market downturn and continuing business consolidation, Hong Kong needs to be on the lookout for business opportunities. As China’s most international city, Hong Kong stands to benefit considerably in the years to come from China’s grand strategy known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The BRI was first proposed by President Xi Jinping in 2013, comprising two main components: the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. The aim is to expand trans-continental connectivity by promoting economic, political and cultural co operation from Asia to Africa and Europe. The BRI is expected to connect 4.4 billion people in more than 60 economies with a gross economic volume of about US$22 trillion.

In 2015, the development blueprints for the BRI were outlined. The value of the proposed BRI-related infrastructure investment in China amounts to some US$160 billion, with total investment in countries along the route expected to reach almost US$900 billion. In implementing this ambitious BRI strategy, enormous opportunities will be created for Hong Kong companies and service providers. As the economic centre of gravity continues to shift east, Hong Kong is poised to become the “super connector” linking Chinese maritime companies to Asia and Europe, leveraging its geographic position, international connectivity, and institutional advantages under “One Country, Two Systems”.

Above all, the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, which links China with Europe through the South China Sea and Indian Ocean, will create fresh demand that supports the long-term growth of the shipping industry. At the same time, international maritime service providers along the Belt and Road will find it beneficial to establish regional offices in Hong Kong, using its maritime services to tap into the mainland market. China has already emerged as a major shipping centre [6] and the world’s biggest shipbuilder. Commercial principals of Chinese shipping companies might also find it advantageous to set up or augment their presence in Hong Kong, which boasts the world’s fourth-largest shipping register.

In forthcoming articles, we will discuss the developments of different maritime service sub-sectors in Hong Kong, including ship broking, ship management, marine insurance, ship finance and maritime law.

[1] According to Statistics on Business Performance and Operating Characteristics of the Transportation, Storage and Courier Services Sector in 2014, the following entities are grouped under the cross-border water transport industry: Ship agents and managers; local representative offices of overseas shipping companies; ship owners of sea-going vessels for passenger transport; ship owners of sea-going vessels for freight transport; operators of sea-going vessels for passenger transport; operators of sea-going vessels for freight transport; ship owners and operators of passenger vessels moving between Hong Kong and the ports in the Pearl River Delta (PRD); and ship owners and operators of freight vessels moving between Hong Kong and PRD ports. The cross-border water transport industry is taken as a rough indication of Hong Kong’s shipping industry for statistical comparison of business establishments. However, it excludes, among other things, ship brokers, insurers, finance companies, surveyors, and classification societies.

[2] For instance, OCCL and COSCO posted YOY gains of 19% and 8%, respectively, in 2014.

[3] In the Summary Statistics on Shipping industry of Hong Kong for September 2015, the shipping industry refers to such industry groups as ship agents and managers; ship owners of sea-going vessels; operators of sea-going vessels, and shipbrokers. Statistics on business activities of the following areas are excluded: shipyards; boatyards; ship surveyors; maritime insurance; maritime legal services; ship finance; and classification societies.

[4] Asian Economic Integration Report 2015, Asian Development Bank

[5] The 12 members of the TPP are: Australia, Canada, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, the US, Vietnam, Chile, Brunei, Singapore and New Zealand

[6] In 2014, seven out of the world’s top 10 ports with the highest throughput were in China, namely Shanghai, Shenzhen, Hong Kong, Ningbo, Guangzhou, Qingdao and Tianjin.

| Content provided by |

|

Editor's picks

Trending articles

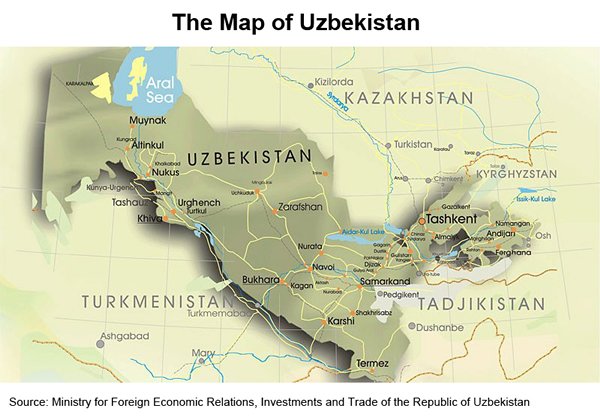

Uzbekistan: An Uncharted Central Asian Market

One of the only two double-landlocked[1] countries in the world, thus lacking any direct ocean access, Uzbekistan is also the most populous country in Central Asia. Its 30 million-plus population, however, has yet to emerge as a strong and sizeable consumer market, largely on account of the country’s inadequate infrastructure and its bewildering array of government controls and regulations. In a bid to reclaim the country’s centuries-old status as one of the key regional centres of commerce along the Asia-Europe trade routes, the Uzbek government has put in place an ambitious five-year plan, with US$55 billion earmarked to modernise its industry and develop new infrastructure. This, together with the extension of its economic cooperation with China as part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), is seeing Uzbekistan bidding to reinvent itself as a vibrant, linked-in investment destination along the route of the ancient Silk Road. Despite these alluring prospects, however, Hong Kong traders are advised to pay close attention to the many practical challenges that could easily derail this development process.

The Largest Underdeveloped Central Asian Market

Highly focused on the growing and processing of cotton, fruits, vegetables and grain (wheat, rice and corn), Uzbekistan, is also a world leader in terms of its gas, coal and uranium reserves. The nation’s 30 million-plus population makes it the most populous country in Central Asia (accounting for 45% of the total population in Central Asia in 2015). This however, has not led to the formation of a lucrative consumer market, despite the country enjoying average GDP growth of more than 8% per annum over the past decade.

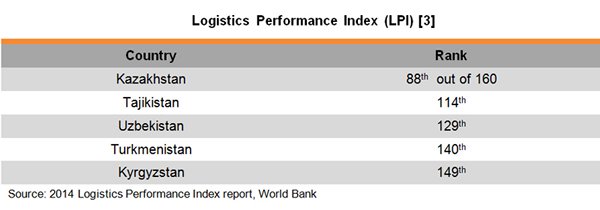

In terms of economic development, it has often been said that Uzbekistan lags behind many other Eurasian nations – notably Russia and Kazakhstan – by as much as 20 years. Its lack of modern infrastructure and its myriad of state controls and regulations with regard to foreign exchange and customs have made Uzbekistan less competitive in the global trading and investment environment. Crucially, it has also been seen as a less attractive trading partner than Kazakhstan, its immediate neighbor.

In order to remedy this, in May 2015, the Uzbek government announced a five-year plan to modernise its industry and develop new infrastructure. In total, this will involve investment of US$55 billion in 900-plus new projects in the gas and petrochemical sectors, as well as the construction of new roads and airports. This – together with the signing of various bilateral and multilateral cooperation agreements, most notably a June 2015 undertaking regarding enhanced economic cooperation with China as part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – intended to reboot the country’s economy and bring its infrastructure up to speed.

Following years of close trade and business ties, the Sino-Uzbek relationship has continued to improve dramatically. In late 2013, the Uzbek government signed some US$15-billion of investment deals with regard to the exploitation of oil, gas and uranium fields. More recently, a new agreement was signed with China in June 2015. This will focus on the extension of economic co-operation as part of BRI and will see increased bilateral co-operation in a number of sectors, including business, transportation and telecommunications. Bulk stock trading, infrastructure construction and the development of industrial park projects are also covered under the terms of the agreement.

The rapid development and extension of Uzbekistan’s railway and road networks, including a 19kilometre railway tunnel connecting the capital city, Tashkent, with the populous Ferghana Valley, is an early sign of the success of this initiative. As one of the developing countries along the Belt and Road and a founding member of the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), Uzbekistan has been keen to rapidly improve its railway network and has been ordering locomotives from manufacturers on the Chinese mainland.

On the back of its rich mineral resources – particularly its petroleum, natural gas, coal and uranium – Uzbekistan’s energy sector has long played a leading role in the country’s economic development and will remain a key factor in luring foreign investment. The country, however, is also looking at upgrading away from the simple production of raw materials, such as cotton, fruits, vegetables and grain, to the higher-value-added food processing and textile industry sectors. Such a development will naturally give Hong Kong companies the opportunity to provide a variety of support services, including those relating to trading and marketing.

A Logistics Player in Its Infancy

As one of the only two double-landlocked countries in the world (with its closest access point to open sea being located nearly 3,000 km away), Uzbekistan relies almost exclusively on its land connections with Kazakhstan (in the north and northwest), Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan (to the east and southeast), Turkmenistan (southwest) and Afghanistan (south). The Latvian seaport of Riga, however, is the most important transit point for Uzbek commodity exports (oil and oil products, fertilizers and automobiles), with some Uzbek companies even owning warehouses in the port. The Iranian ports, by contrast, are mainly used for raw cotton exports.

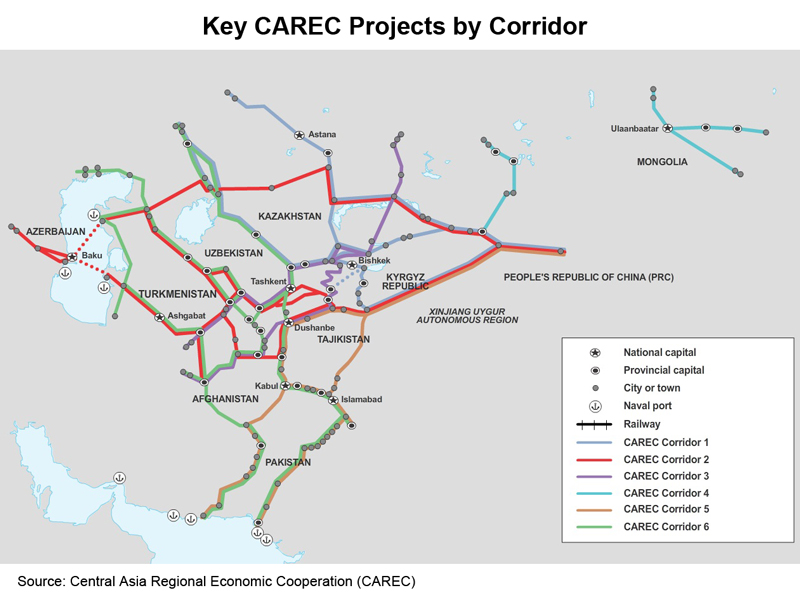

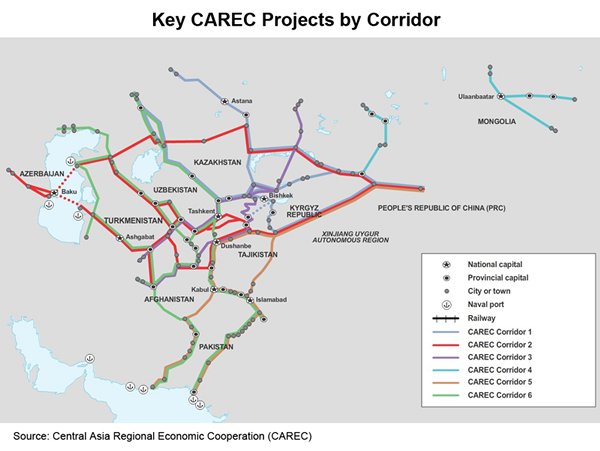

Straddling many of the shortest transit routes connecting Europe and Asia, Uzbekistan is located at the heart of Transport Corridor Europe–Caucasus–Asia (TRACECA) and three of the six Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation (CAREC[2]) corridors, namely (i) Corridor 2-a, 2-b (Mediterranean–East Asia), (ii) Corridor 3-a, 3-b (Russian Federation–Middle East and South Asia), and (iii) Corridor 6-a, 6-b, 6-c (Europe–Middle East and South Asia). Dating back to Soviet times, rail and road transport have been the country’s key and cheapest means of transport. According to current estimates, some 95% of cargo travelling through or to Uzbekistan still travels by road or rail.

Although land transport plays an important role in Uzbekistan’s international connectivity, only one-sixth of its 4,200 km-long railway tracks are electrified, while less than 10% of its 43,000-km roadways have international applications. With the routing of most of the country’s inbound traffic (high-value machinery, capital equipment, electronics, and consumer goods) largely controlled by foreign shippers and the routing of most of its outbound traffic (mainly raw materials such as cotton) controlled by the government, Uzbekistan’s trucking and container management industries are somewhat underdeveloped.

According to the country’s leading logistics association – the 2009-established Association for the Development of Business Logistics (ADBL) – almost all of the modern trucks and containers used for transporting goods in and out of the country are owned by foreign logistics players. By contrast, Uzbek logistics companies lack a sufficient number of trucks that comply with Euro IV and Euro V, the EU vehicle emissions standards, to compete with foreign players in terms of delivery to and from the wider European market.

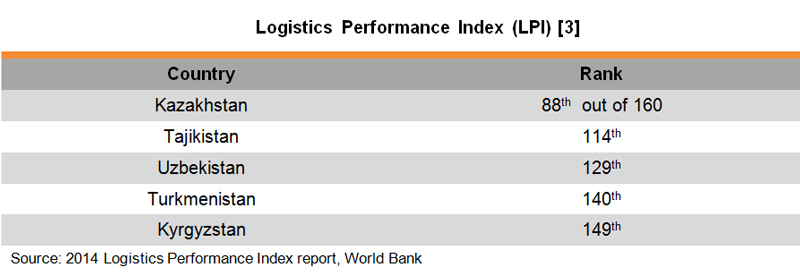

According to ADBL, both the concepts of multimodal logistics and supply chain management are new to Uzbek companies. While the international logistics business in Uzbekistan has been largely expat-dominated, it is still underdeveloped in terms of local participation. This is one reason why Uzbekistan has been lagging behind its peers, such as Kazakhstan, in terms of cross-border logistics performance.

In order to promote multimodal logistics and better connect Uzbekistan with the global supply chain networks, ADBL has been working closely with its 40-plus associated members (local and foreign companies) and its 20-plus partners, such as the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the National Air Carrier, the National Railway (UTY) and the Association of International Road Carriers of Uzbekistan (AIRCUZ). This has seen the launch of a number of new initiatives, including sending university teachers and scholars to Germany and Poland to master the latest international logistics practices and to help establish cooperation with foreign professional logistics associations, as well as with representatives of those foreign companies active in Uzbekistan.

In order to improve efficiency and enhance its multimodal transport operations and remain competitive as a regional link, Uzbekistan is also striving to upgrade its logistics infrastructure through a focus on building new roads and airports. Other than the projects previously announced as part of its domestic development plans, such as the five-year, US$55 billion plan announced in May 2015, Uzbekistan is also actively participating in a number of regional cooperation programs, such as the CAREC Program. As of 2015, Uzbekistan has mobilised more than US$5.3 billion across 15 projects (4 completed and 11 ongoing) through CAREC, including not only road investment projects, but also railway modernisation and electrification initiatives.

These projects have not only enhanced Uzbekistan’s international trade by improving its access to neighboring countries and seaports, but have also introduced market modern technologies – such as advanced track-laying equipment and efficient track maintenance systems – to the country. This has bolstered Uzbekistan’s capacity in the wagon construction and maintenance sectors, making it one of only three former Soviet Union countries, together with Russia and Ukraine, to have such facilities.

With the aim of strengthening regional and inter-regional cooperation between the CAREC countries and other nations by reducing travel time and maximising the efficiency of transport routes, the CAREC Federation of Carrier and Forwarder Associations (CFCFA), a non-government and non-profit organisation was established in 2009. Later incorporated in Hong Kong in May 2012, it now focuses on the standardisation and adoption of international best practices, cross-border and corridor development, and organisational development and funding. It is expected that this initiative, as well as several others, will result in expanded trade via the CAREC corridors. It is anticipated that, by 2020, the value of inter-regional trade will have increased fivefold from a 2005 baseline of US$8.0 billion, while the costs incurred for border crossing point clearances will decrease by 20% (from a 2010 baseline).

These targets are very much in line with those of the BRI, in particular the development of transport infrastructure and the facilitation of the free flow of investment funds. One of the largest projects in terms of Chinese-Uzbek economic cooperation and the longest railway underground corridor in Central Asia is the Angren-Pap railway tunnel. With the work being conducted by the China Railway Tunnel Group, this 19.2km tunnel connects the populous Ferghana Valley (the site of three administrative regions – Ferghana, Andizhan, and Namangan) with the rest of Uzbekistan. Its success is being seen as an early sign of how Chinese investment, technology and development experience can help Central Asian countries develop.

Poised to become an international logistics gateway between China and Europe following its completion in August 2016, the Angren-Pap railway is expected to be used by some 600,000 passengers and to convey around 4.6 million tons of goods during its first year of operation. It is hoped that it will also reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the region by about 200,000 tons annually.

In terms of air transport, Uzbekistan boasts one of the best air networks in Central Asia, though its air transport is mainly used for the export of high value, but low volume, fruits and vegetables, equipment and parts and consumer goods. The Navoi Airport international distribution centre, built through a partnership between South Korea and Uzbekistan is seen as a good model for the future development of logistics centers, dry ports, multimodal cargo hubs, and refrigerated warehouses in the country. As part of the project, Korean Air provided technical, operations and sales support for the logistics centre, while Uzbekistan Airways helped obtain the necessary approvals and funding for the development.

Situated at the heart of CAREC corridors traversing Uzbekistan, the Navoi International Airport is a complex logistics hub capable of handling 100,000 tons of freight annually. Ideally positioned for handling transit air cargo going to western Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan and Tajikistan, it is set closer to Samarkand (the most famous city in modern Uzbekistan) and many other historic cities (notably Bukhara and Khiva) than Tashkent International Airport, ensuring it is also suitable for use by Silk Road tourists.

With its improving transport infrastructure, Uzbekistan is now better positioned to attract foreign investors, bringing in not only funding, but also technology and the production facilities needed to create new jobs and to diversify its industrial and export base. Uzbekistan’s automotive, agricultural machinery manufacturing, biotechnology, pharmaceuticals and information and communications technology sectors have all increased in importance since the country achieved independence in August 1991. General Motors, for instance, began producing Chevrolets in the country in November 2008.

As the country’s largest source of foreign investment and its second largest trading partner (behind only Russia), China currently has some 500 companies and 5,000 nationals operating and working in Uzbekistan. These include Huawei, The Peng Sheng Development Co – China’s largest private investment in Uzbekistan and also home to the largest ceramic tile producer in Central Asia, Tencent and ZTE, which has established the first smartphone production line in Central Asia. The number of Chinese companies investing in Uzbekistan is expected to increase as the BRI progresses and Uzbekistan becomes more investor-friendly.

Pre-Requisites for Realising the Country's Full Potential

Uzbekistan has considerable long-term promise in terms of logistics and urban development cooperation, while there are also opportunities in term of financing and listings, in line with the gradual process of increased privatisation and market opening. To this end, Hong Kong, as a facilitator for infrastructure projects and an international financial and trading hub, is well-positioned to help Uzbek companies through its well-developed cluster of business and professional service providers.

For the short term, though, Uzbekistan is still in the process of improving and upgrading both its hardware (i.e. its infrastructure) and its software (i.e. its law enforcement and foreign trade and investment liberalisation policies). Unreliable customs clearance procedures and the arbitrary application of regulations at border controls, as well as widespread government interventions, will continue to give Hong Kong traders and investors concerns that must be addressed if Uzbekistan is determined to realise its full potential, in terms of both its own development initiatives and those outlined as part of the BRI.

As Uzbekistan does not have a consulate or any diplomatic representation in Hong Kong, securing a visa can be quite costly and time-consuming for Hong Kong companies. With no distinction made between tourism and business visas, an HKSAR passport holder needs to obtain a Letter of Invitation (LOI) from a local institution in Uzbekistan, usually an authorised travel agency.

Together with the LOI, the applicant can submit the visa application directly to the Uzbek Embassy in Beijing or the Uzbek Consulate in Shanghai. Alternatively, applications can be made via the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Uzbekistan through the same local Uzbek institution that provided the LOI (i.e. usually an authorised travel agency). Once the application has been approved, the applicant can collect the visa at any Uzbek consulate or send a request to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to collect the visa upon arrival at Tashkent International Airport[4]. It can easily take more than a month to complete all the steps and secure the necessary visa. This makes time-sensitive business visits extremely difficult, if not impossible.

On the trade front, although it is Hong Kong’s second largest export market in Central Asia, behind only Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, unlike its neighbors, is neither a WTO member nor a member of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU). Kazakhstan has been a member of the WTO since November 2015 and an EAEU member since January 2015, while Kyrgyzstan has been a WTO member since 1998 and an EAEU member since December 2015. Uzbekistan applied for WTO membership in 1994 but has yet to be ratified. At the same time, problems with the Uzbek customs regime – largely stemming from a lack of transparency with regard to the enforcement of trade rules and arbitrary customs regulations and seizures – have been widely covered by the international media and frequently complained about by importers.

Summing up the feeling of a number of foreign companies operating in Uzbekistan, one said: “The door for investment in Uzbekistan is wide open, yet the door for profits repatriation is rather narrow, if not completely closed.” Strict foreign exchange controls have also made money transfer outside of the country very complicated and costly. The existence of black market rates, which can be as much as 100% higher than the official rates, has made the business community loathe to use more formal banking and trade finance services.

[1]A double-landlocked country is defined as a landlocked country surrounded by other landlocked countries. Except Uzbekistan, Liechtenstein, surrounded by Austria and Switzerland, is the only other double-landlocked country in the world.

[2] The CAREC Program is a partnership of 10 countries (Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan) and six multilateral development partners (Asian Development Bank (ADB), European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), International Monetary Fund (IMF), Islamic Development Bank (IsDB), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and World Bank) all working to promote development through cooperation, leading to accelerated economic growth and poverty reduction.

[3] The LPI measures a country’s trade logistics performance using a number of parameters. Countries with high LPI scores have lower trade costs and are better connected to the global value chain.

[4] More details about the visa application process can be found at http://www.mfa.uz/en/consular/visa/.

| Content provided by |

|

Editor's picks

Trending articles

China's 'One Belt, One Road' - An Opportunity Britain Must Grasp

By the Economist Intelligence Unit

The UK’s relationship with China was centre stage during President Xi’s visit to the West last week, with many wondering what’s next for the economic relationship. The answer is President Xi’s ‘One Belt, One Road initiative’ (OBOR), which could be a gamechanger for China, and open up new opportunities for British business……

Please click here for the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

The Five Key Elements Shaping UK-China Economic Relations

By the Economist Intelligence Unit

It is no accident that China’s President, Xi Jinping, will attend the UK-China Business Summit during his visit to the Britain this week, since business, trade and investment lie at the heart of the future agenda for developing relations between the two countries. While deals are expected to be signed across a range of sectors, and there is anticipation of further co-operation in financial markets, there are five key elements in the future of UK-China economic relations, which can be encapsulated in the following acronyms: RMB, CIPS, OBOR, AIIB, and FTA. These are the steps on the ladder to help the UK achieve its stated objective of becoming ‘China’s best partner in the West’……

Please click here for the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Repaving the Silk Road

By Graham Norris (Senior Director of Communications, AmCham China)

When facing adversity, it makes sense to draw on the experience of history, and with 5,000 years to review, China’s leaders have no shortage of comparisons to make with the current era. China is on the rise economically and politically, but the economy is struggling to transition to a more sustainable mode of development. Moreover, infrastructure-driven growth has created an overcapacity hangover that threatens to unravel excessively leveraged lending systems in the provinces. What to do?...

Please click here for the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Hitching a Ride Along the New Silk Road

AmCham China

Since Chinese President Xi Jinping initially announced the One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative in 2013, it has become a source of significant curiosity and discussion to understand what exactly the initiative will entail and its implications for those inside and outside of China. While OBOR is still taking shape, its scope has emerged as incredibly broad, covering over 60 countries, with finance, trade and diplomatic goals. Additionally, the economic aim of the initiative is to bulwark China’s domestic economy in the face of slowdown and restructuring. Both the amorphous nature of the initiative and its domestic orientation mean there are limited ways for foreign business to capitalize on the initiative. However, two possible channels still exist: partnering with Chinese firms on OBOR projects; and seeking opportunities through the other countries involved in the initiative…

Please click here for the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

How the New Silk Road Reshapes Business

AmCham China

Most analyses of China’s One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative tend to focus on two core aspects of President Xi Jinping’s ambitious vision of a more interconnected Europe, Asia and Africa: the political motivations behind it, and whether the economic realities even render Beijing’s plans for a modern Silk Road feasible. While the political focus tends to be on Beijing looking eastward for alliances in the wake of an increasing post-pivot US presence and the recent conclusion of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (which includes the US, but not China), economic conditions in China are increasing the urgency and necessity of new opportunities to put its vast manufacturing powers to use. But despite the many criticisms and concerns over China’s political objectives and whether or not OBOR will realize its full potential, this initiative has already begun to alter the Eurasian economic and business landscape through its creation of financial capital, pushing of economic and legal reforms, and increased institutionalization of the region…

Please click here for the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Could India Prove to be One of the BRI's Key Development Partners?

Country yet to fully commit, although many commentators see clear benefits stemming from participation.

Given the size and the scope of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), India is certain to play an important role in the project, particularly as the proposed Maritime Silk Road (MSR) routes extend into the Indian Ocean. While sharing a long border with China, trading ties between these two major Asian nations have been relatively small, due to both historical and geographical factors, with the mighty Himalayas lying between the two. In addition, the Indian economy, long seen as lagging far behind China's, is finally showing strong growth, making enhanced trade a far more appealing prospect for both parties.

Many now see India as a "sweet spot" at a time when a substantial number of economies throughout the world – including China's – are slowing down. Confirming the country's importance to the BRI project, Ben Simpendorfer, head of Silk Road Associates, a Hong Kong-based consulting firm, said: "India is one of the Silk Road's largest economies and so must play a significant role in the Initiative."

One of the key aims of the BRI is to help China export its excess capacity in a number of sectors, notably steel and cement. Inevitably, this will lead to massive investment in a huge variety of infrastructure projects, including roads, railway lines and seaports.

Dr Srikanth Kondapalli is Professor of Chinese Studies at New Delhi's Jawaharlal Nehru University. He says: "While the BRI is aimed at addressing these excess capacities, it will also bring a tremendous supply of Chinese capital to the neighbouring regions in Asia and beyond."

In many ways, at the heart of the BRI is a complex matrix of infrastructure projects, with many of them likely to have a huge impact on India. With regard to this, two of the most notable projects are the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor (BCIM) and China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

India is, of course, fully aware of the strategic element of the BRI, which some say explains why it has yet to take an official position on the project. There are also a number of sensitivities that will need to be addressed. For one, the BRI is likely to extend into Pakistan, with a number of projects set to be built in Pakistan-controlled Kashmir. India and Pakistan's problematic relationship is likely to cast a long shadow over any project involving the two countries.

In other areas of the BRI, however, India has proved to be a more than willing participant. The country has already signed up to join two of the pan-regional financial institutions likely to be key to the success of the project – the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the New Development Bank. The three banks are likely to be the conduits for the funding for many of the proposed infrastructure projects, said to involve a total spend of some US$8 trillion.

Despite these positive moves, many analysts remain divided as to how the BRI will affect India and its likely impact on the country's relations with its neighbours. The optimists go as far as to believe that, far from exacerbating regional tensions, the Initiative could even lead to stronger economic ties between India and Pakistan.

According to ICRIER, a Delhi-based think-tank, the potential value of the two-way trade between India and Pakistan – should all tariff and non-tariff barriers be removed – is $30 billion, 15 times the current level of trade. Should the BRI and its associated infrastructure developments pave the way for such expansion, it would clearly be to the benefit of all parties concerned.

At the level of individual companies, it is highly like that many of the larger Indian businesses will benefit from their country's participation in the BRI. Such involvement would entitle India's more substantial businesses to bid for a number of the BRI-related projects, although they would face tough competition from companies in Korea, Taiwan and China. Kondapalli, though, is philosophical about the prospects for Indian companies, saying: "Anyone could walk away with a billion dollars' worth of projects."

There are certain areas where Kondapalli's optimism could clearly be vindicated. India is highly competitive in both the software and automotive sectors for instance. In terms of infrastructure, though, it is the Chinese firms that are already involved in many of the relevant construction projects.

Although Chinese companies are already working on projects in the Hyderabad area, it is thought that future developments might be undertaken on more of a joint venture basis between Chinese and Indian companies. This would see the domestic firms focussing on government relations, as well as sourcing local labour and materials.

Simpendorfer believes that such partnerships will characterise many of the future developments, saying: "Indian corporations will inevitably play a critical role when it comes to leading consortiums or partnering with Chinese firms as part of large-scale construction projects."

Tsering Namgyal, Special Correspondent, New Delhi

| Content provided by |

|

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Enhanced Border Trade and New BRI Privileges Set to Boost Guangxi

With the mainland government highlighting the role a number of key border regions will play in the ongoing development of the Belt and Road Initiative, several such regions have been granted special privileges, most notably Guangxi.

In January this year, the State Council issued its Opinions on Several Policy Measures in Support of the Development and Opening-up of Key Border Regions (Guofa No.72 [2015]). It outlined official support for the development of a number of key border regions, including several pilot zones for development and opening-up, national-level border ports, border cities, border economic co-operation zones, and cross-border economic co-operation zones. The policy specified that these designated regions would all have a leading role in China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

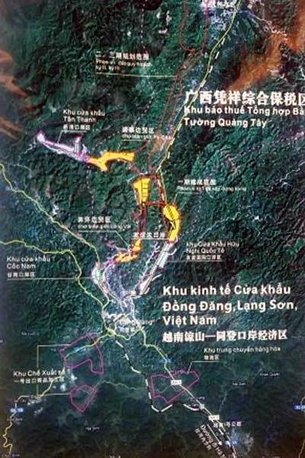

One of these designated areas is Guangxi, an autonomous region in South China bordering Vietnam and one with a long trading history with its neighbour. In order to determine just how Guangxi will benefit from the new policy measures and to get a greater understanding of the potential for small-scale cross-border business in the region, representatives of the HKTDC's Guangzhou Office recently visited two cities – Dongxing and Pingxiang – located along the Vietnam border.

I. Guangxi-Vietnam Border Trade: A Flourishing Sector

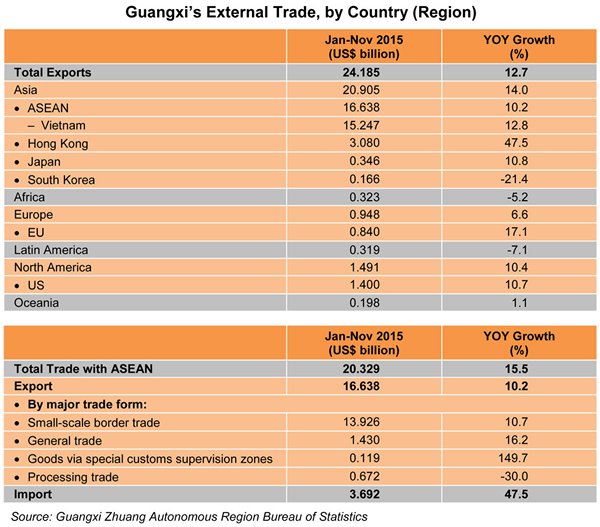

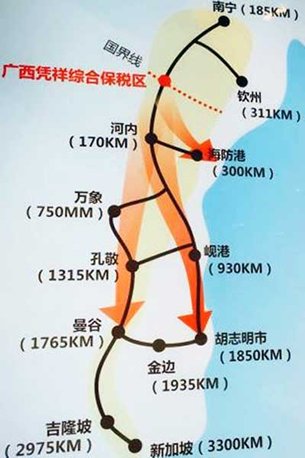

In light of Guangxi's advantage in bordering an ASEAN country by land and by sea, the Central Government has designated the region as an important staging post in the development of the BRI. This decision reflects both the region's geographical advantage and its trading history with Vietnam and a number of other ASEAN nations.

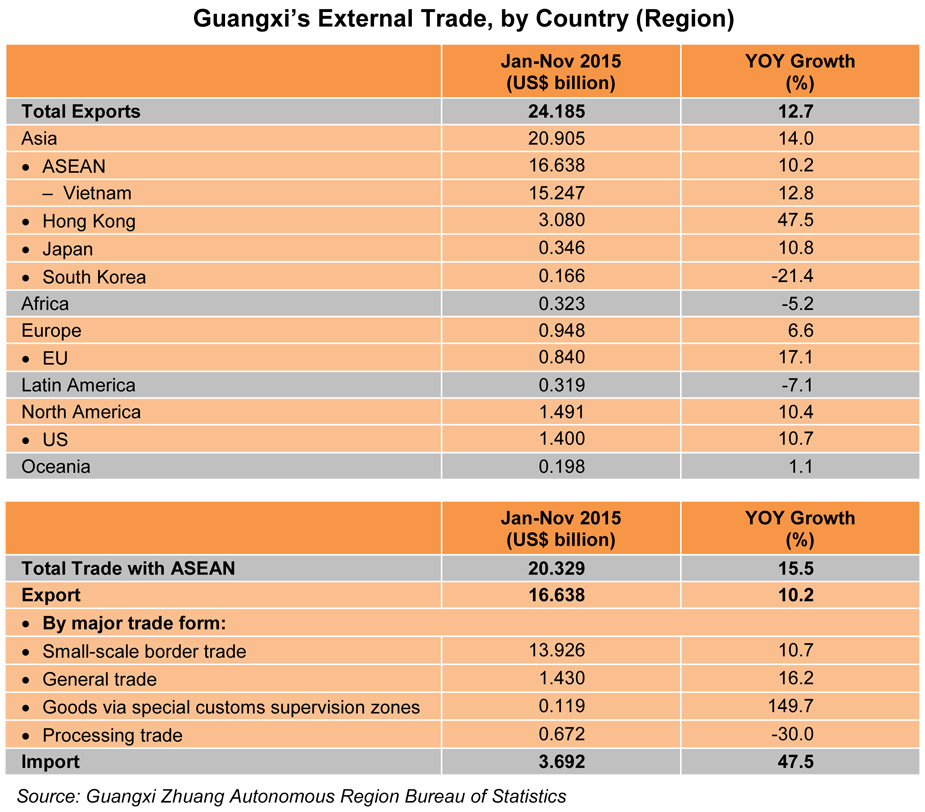

In 2015, according to the Guangxi Statistics Bureau, the total value of trade in the region was Rmb319 billion, an increase of 15% year-on-year. Of this, the total value of small-scale border trade was Rmb106 billion – up 17.1% year-on-year – accounting for 33% of total trade. In terms of trading partners, the value of imports/exports between Guangxi and ASEAN was Rmb181 billion – up 19.6% year-on-year, accounting for over half of total trade. Further afield, the US import/export value was Rmb16.4 billion – up 8.0% – while the EU import/export value was Rmb10.1 billion, up 16.2%.

The term "small-scale border trade" refers to all trading activities (including such things as barter trade and spot trade) between designated enterprises in China and enterprises or other trading entities in the border regions of neighbouring countries, as conducted through land ports specified by the Central Government. These designated enterprises are those businesses granted small-scale border trade rights by border counties or border city districts along China's land border, which have been approved by the Central Government to conduct external trade.

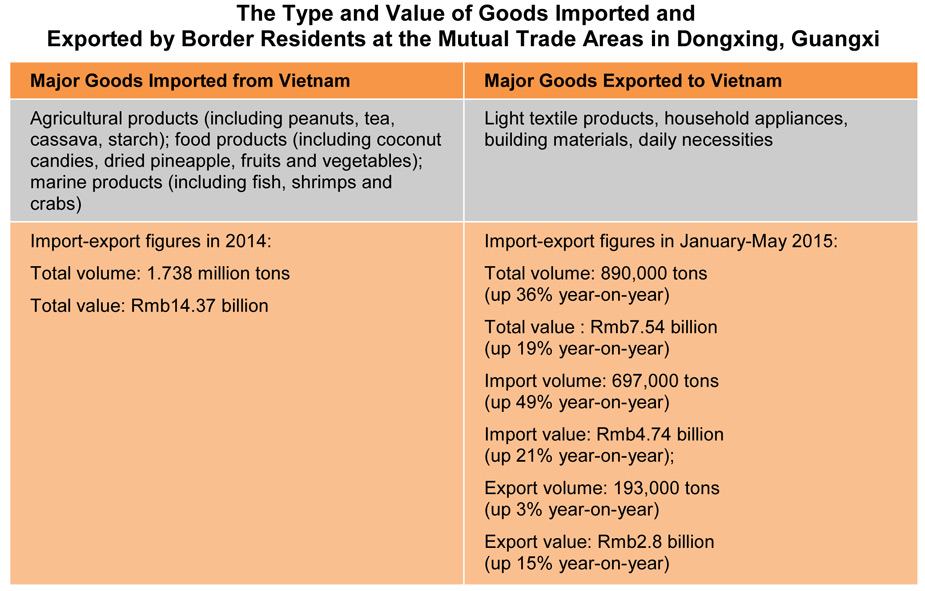

Pingxiang, a county level city in Guangxi, is China's largest border trade port. Dongxing, another major port, lies just 100 metres away from Vietnam's Mong Cai port and is the only Class 1 port in China bordering Vietnam by both land and by sea. A total of 6.15 million border crossings were recorded at the Dongxing port in 2015.

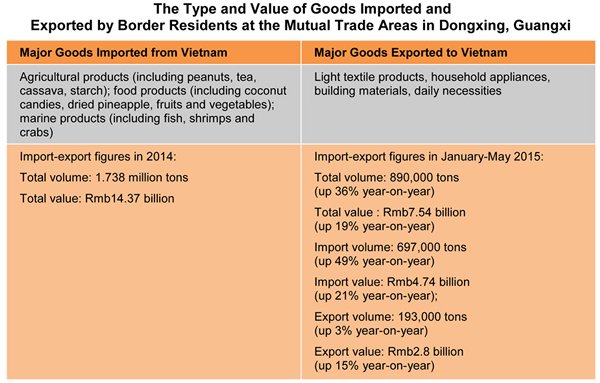

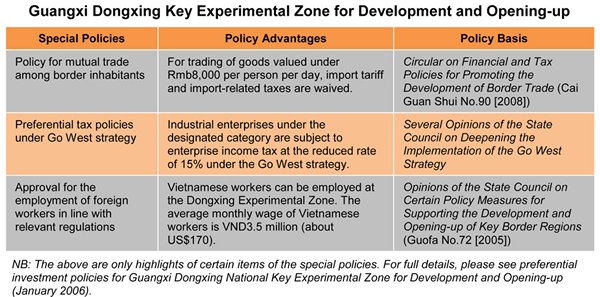

Mutual trade among border inhabitants refers to goods exchanged between border area inhabitants within 20 kilometres of China's land border. Trade can only be conducted at government-approved open zones or designated markets and at a level that does not exceed the prescribed amount or quantity. For daily goods imported by way of mutual trade among border inhabitants (excluding those mutual trade import goods not on the tax exemption list), and with a value of under Rmb8,000 per person per day, import tariffs and import-related taxes are waived. For daily goods exceeding the value of Rmb8,000, import tariffs and import-related taxes will be levied on the portion exceeding the prescribed limit.

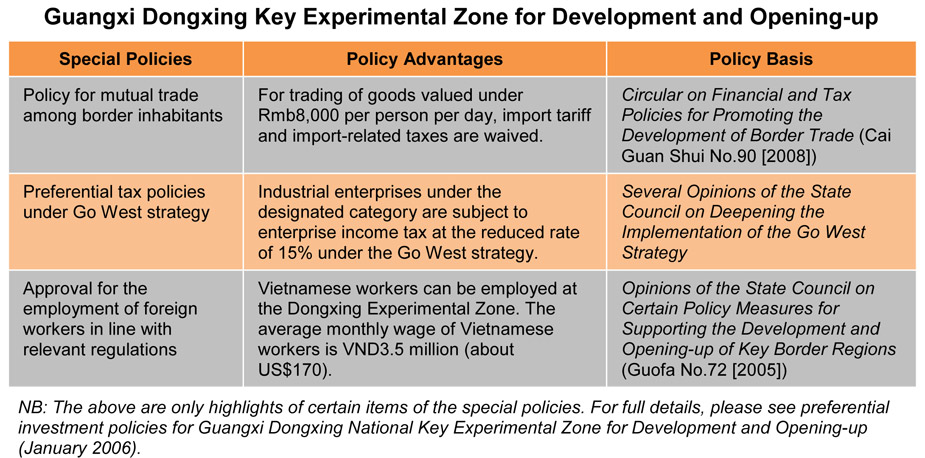

II. Special Policies for Key Border Regions in Guangxi

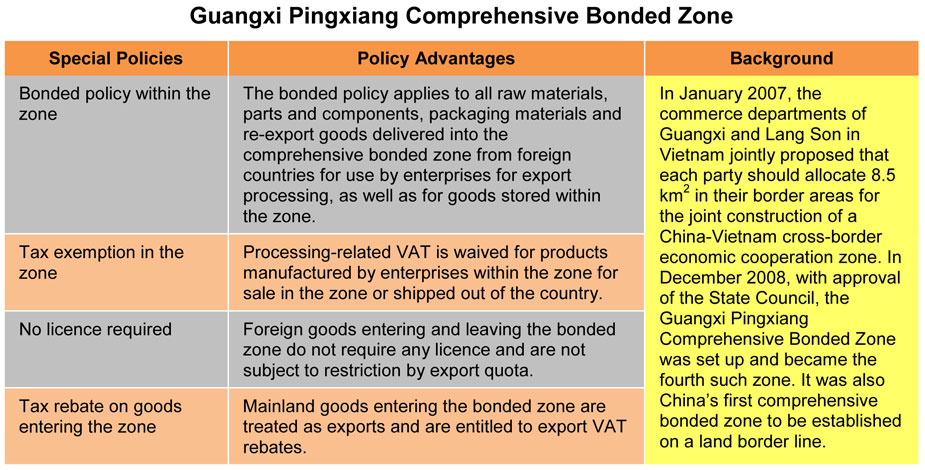

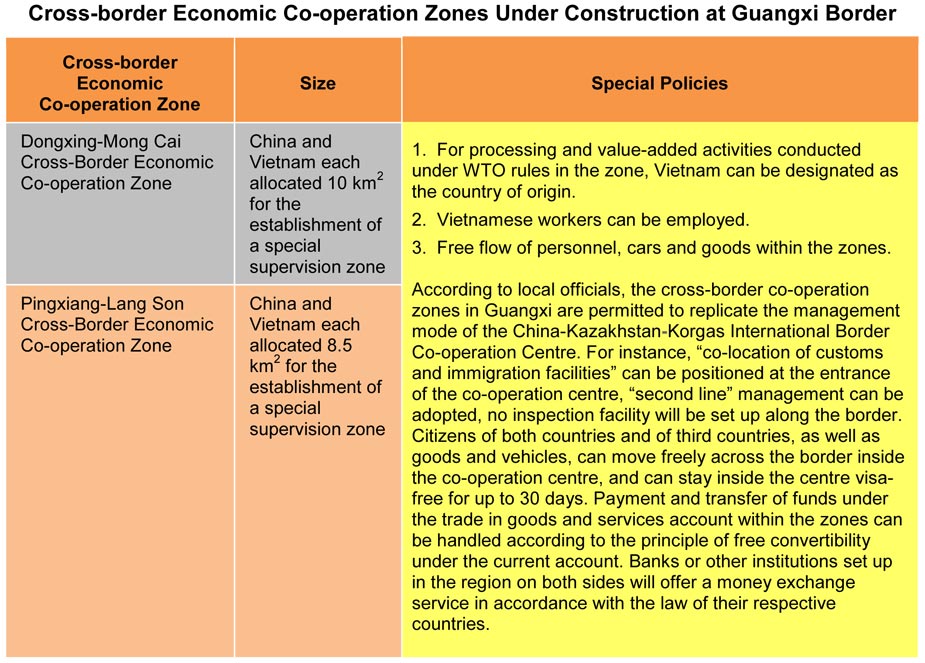

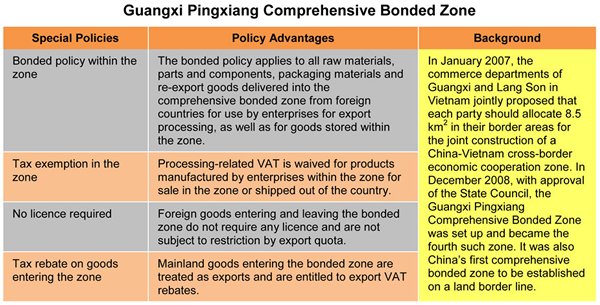

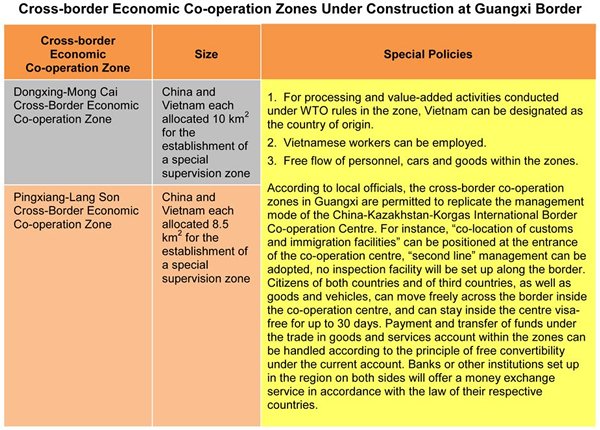

The Central Government divides key border regions into five distinct categories: key experimental zones for development and opening-up; national-level border ports; border cities; border economic co-operation zones; and cross-border economic co-operation zones (for further details, please see Guangxi-Vietnam Border Trade: List of Key Border Regions). Outlined below are the policy advantages of the Dongxing Key Experimental Zone for Development and Opening-up, the Pingxiang Comprehensive Bonded Zone, and the Cross-Border Economic Co-operation Zone (currently under construction in Guangxi).

Cross-border economic co-operation zone refers to a special area set up in the vicinity of the border between two countries. The zone is granted special financial, taxation, investment, trade and industrial dispensations. Certain regions within the zone are subject to cross-border special customs supervision. These regions are sub-regional economic co-operation zones entitled to the preferential policies applicable to export processing zones, bonded zones and free trade zones.

In an article published in the People's Daily on 10 December 2015, Gao Hucheng, China's Minister of Commerce, stated that China had already set up 17 border economic co-operation zones in its border regions. In addition to the China-Kazakhstan-Korgas International Border Cooperation Centre, which was established jointly with Kazakhstan, China is currently negotiating with Laos, Vietnam and Mongolia with regard to establishing further cross-border economic co-operation zones.

III. China-Vietnam Small-Scale Border Trade: Big Opportunities

1. Dongxing: Bright Prospects for Cold Chain Logistics

Vietnam produces a vast variety of marine products, with the Dongxing Experimental Zone an important trading port for the import of such items into China. According to official figures, more than 100 containers of marine products are exported from Vietnam into the Dongxing Experimental Zone every day, representing an annual transaction volume of more than 200,000 tons. In 2013, Dongxing exported about 2,355 tons of processed marine products, with an export value in excess of US$11.6 million.

According to Chen Zhenghao, deputy general manager of Global Green (Dongxing) Frozen Food, a company engaged in the processing of marine products in Dongxing, the city has a number of advantages with regards to this sector. Capitalising on the local policy governing mutual trade among border inhabitants, marine products imported from Vietnam are exempt from import tariffs and import-related taxes. Additionally, local companies can employ Vietnamese workers in Dongxing without having to make social insurance payments on their behalf, a considerable saving on labour costs. Finally, with the marine products processing industry in the nearby port city of Zhanjiang approaching saturation point, excess requirements are being passed on to Dongxing and boosting its growth.

Unfortunately, however, Dongxing's cold chain logistics resources are somewhat underdeveloped, with a lack of storage resources and space pushing up the costs of such facilities. According to Chen, the cold storage fee in Dongxing is Rmb7 per ton a day (for cold storage under -18°C), while in Zhanjiang the fee is only Rmb3.5 per ton. Similarly, the wharf loading and unloading fee in Dongxing is Rmb50 per ton and the warehousing management fee is Rmb200 for each use, all of which translates into a higher total cost. In view of this, Chen believes there are now huge business opportunities in the local cold chain logistics industry.

2. Industrial Relocation Spurs New Logistics Routes

The Friendship Gate in Pingxian is China's major land port for exports to ASEAN and has a throughput of more than 700,000 tons of import/export goods and more than 80,000 cross-border vehicles a year. Puzhai, a sub-district of Pingxiang, is home to China's largest fruit market for trade with ASEAN. According to official figures, a total of 1.623 million tons of fruit were imported and exported via Pingxiang in 2014, most of which was transported by road. Every day, more than 600 container trucks pass through Puzhai.

In light of the rising labour and production costs in China over recent years, many multinational corporations – including Samsung, Nokia, LG, Foxconn and Canon – have established factories in areas close to Hanoi, the Vietnamese capital. As a result, a number of ancillary companies also have relocated to the border areas between Guangxi and Vietnam in order to take advantage of the Pingxiang Comprehensive Bonded Zone, which allows them to conduct bonded processing as well as to employ Vietnamese workers as part of a move to lower labour costs. As a consequence, a logistics land route running from Hanoi to Pingxiang, and then on to Hong Kong, has now been established.

According to Li Chuanren, General Manager of Jiedi, a Guangxi-based supply chain company, it currently takes about 14 hours (1,200 kilometres) to travel by road from Hanoi to Hong Kong, with the transportation fee for a 45-foot container being around Rmb30,000. Given the rapid economic development of the Southeast Asian countries and the construction progress of the cross-border economic co-operation zones, local demand for transit warehouses, cold chain logistics, supply chain management and related supporting facilities will inevitably increase.

3. Hong Kong's Tourism Industry and China-Vietnam Cross-border Tour Opportunities

As part of an update to the Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement (CEPA) agreement – signed between the Ministry of Commerce and Hong Kong in November 2015 and due to be implemented as of 1 June 2016 – Guangxi will become the second CEPA pilot region (after Guangdong) in the country.

Guangxi is well-known for its abundance of tourist spots and historical sites. As border trade has become increasingly buoyant in recent years, approval has now been given by both the Chinese and Vietnamese governments for cross-border self-drive tours. According to official figures, Dongxing welcomed a total of 6.711 million tourists in 2015, while the number of tourists received by Mong Cai – the Vietnamese city just across the river – was in excess of one million. During the same year, 22,000 tour groups, representing a total of 150,000 tourists, applied to the Dongxing national border tourism office for entry-exit permits, of which 115,000 were out-of-province tourists.

The new CEPA agreement is widely seen as good news for those Hong Kong service providers looking to access the Guangxi tourism market. Under the agreement, Hong Kong companies in the tourism and hospitality sector can establish a presence in Guangxi and play a key role in integrating the tourist resources of Southeast Asia and the mainland in order to develop new tourist routes and services.

Crystal Ho and Edison Lian, Guangzhou Office

Related article: "State Council Reveals List of Key Border Regions for BRI Development", 26 February 2016.

| Content provided by |

|