Chinese Mainland

Hong Kong Economic Journal - EJ Insight | 12 Jan 2015

India Plans New Industrial Revolution of Its Own

India aims to become a global manufacturing power by focusing on “entirely new industries” such as solar technology, LED lighting, small cars, medical appliances and weapons, Financial Times reported, citing Minister of State for Finance Jayant Sinha.

“What we’re trying to do is massively build out India’s productive capacity,” Sinha told the newspaper in an interview.

“That is, in fact, a veritable supply-side revolution because what we are really trying to do is to position India for a decade or more of sustainable, non-inflationary 7-8 per cent GDP growth. It’s only if we can achieve those kinds of growth rates that we will be able to create the millions and millions of jobs we have to create every year.

India is the world’s third-largest economy after the United States and China, measured on a purchasing power parity basis, but manufacturing makes up only 15 percent of the gross domestic product.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi wants to boost its contribution to 25 to 30 percent of the GDP to help create a million jobs a month in a country with a population of 1.3 billion, the newspaper said.

However, his dream is being hampered by clogged transport infrastructure, a shortage of skills, outdated labor laws that discourage investors, and the reluctance of indebted Indian companies to take on new risks, according to FT.

In order to achieve Modi’s grand vision, the government will seek to meet the country’s vast domestic demand for everything from raw materials to vehicles and home appliances, and then develop internationally competitive industries in new sectors, Sinha said.

“When China became a tremendous electronics manufacturing hub, it did that for smartphones, for instance, which did not exist as a product category,” Sinha said. “It did that in laptops, which did not exist as a product category. They didn’t necessarily replicate what Japan was doing in automotive manufacturing.

“Similarly, I think there will be industries where India will become a global leader, but those are entirely new industries, for instance solar appliances, solar lanterns, solar home systems . . . India is already the world hub for small car design and manufacturing.”

Sinha added: “The Indian economic model is not the same as the Chinese economic model. Ours is a much more innovation-driven, bottom-up approach towards economic growth . . . We will rely on our innovative and world-class firms to be able to unlock these new manufacturing industries of the future.”

The first stage of India’s planned industrial revolution is likely to put more emphasis on public spending for infrastructure than on private investment in new factories.

The government plans to boost public investment by US$25 billion to US$50 billion in the 2015-16 fiscal year, while the country’s railway network seeks to invest US$100 billion in the next five years.

Energy Minister Piyush Goyal has launched a US$250 billion plan for power generation and transmission to double electricity output and achieve Modi’s promise of 24-hour electricity for all by 2019, the report said.

Full content of EJ Insight is available at www.ejinsight.com. Copyright Hong Kong Economic Journal Ltd. Republishing and editing are forbidden without authorization from Hong Kong Economic Journal. If there are any questions, please contact Chris Yeung (chrisyeung@hkej.com) for editorial matters and Margaret Lor (margaretlor@hkej.com) for sales and marketing matters.

| Content provided by |  |

Editor's picks

Trending articles

What is a DTA and how does it work?

What is a DTA and how does it work?

DTA is short for double tax agreement. It is also called double tax treaty (DTT). Countries or states sign DTA’s in order to achieve the following major objectives: avoidance of double taxation, allocation of taxing rights, and exchange of information. DTA’s are negotiated bilaterally between two states and drafted by reference to the framework under the OECD Model Tax Convention.

(I) Avoidance of double taxation

A person earning an income is subject to tax in the state of which he is a resident. Alternatively an income may be taxable in the state in which the income generating activity takes place. But by the operation of the domestic tax rules, the income taxed in one state may also be taxed again in another state. Double taxation may arise in any one of the following three ways:

(a) the conflict of rules adopted by different countries in the determination of tax residence;

(b) the conflict between residence rule in one country and source rule in the other country, and

(c) the conflict of rules adopted by different countries on the source of income.

Example - 1

A Hong Kong company assigns a US national, whose wife and kids are working and living in Canada, to work for its subsidiary in Shanghai for two years. In the absence of any DTA signed between respective countries, the same income of the employee may become taxable in four jurisdictions.

First, double taxation arises from the conflicts between residence rules. The above employee is both a tax residence of Canada and the US as per residence rules of each country. One the one hand, the employee suffers income tax due to his family ties with Canada. That is, his family members work and live in that country. On the other hand, he is a tax residence of the US that imposes worldwide tax on its nationals. Second, double taxation arises from the conflict of source rules between Hong Kong and China. The above employee is subject to income tax as he exercises employment in China, while he is also subject to salaries tax in HK because a contractual relationship has been created following the employment agreement concluded between him a HK company. Third, double taxation arises from the conflict between the residence rules and source rules. Where the employee is taxed in Canada because he has family ties with the country, the same income is subject to tax in China because the employee is performing his duty in China.

(II) Allocation of taxing rights between the signing states

(a) Assignment from HK to China

Let’s study the first example on how the problem of double taxation is solved.

In respect of the double tax claims by the US and Canada, the employee of the HK employer can refer to the Article 4 in the US-Canada DTA to solve the dual residence issue. According to the US-Canada DTA, the employee’s personal and economic relationship (the center of vital interest) with Canada shall take precedence over his US nationality in the determination of residence. In respect of the double tax claims by Canadian and Chinese tax authorities, the employee can avoid double tax as he is entitled under Article 21 of Canada-China DTA to the tax credit in Canada for tax paid to the Chinese tax authority on the income earned in China. Article 21 of Canada-China DTA operates to solve the residence-source conflict. In respect of the double tax claims by the tax authorities in HK and China, the employee can avoid the double tax arising from the clash in source rules by submitting an application for a tax exemption in Hong Kong on the strength of the taxes he has suffered and paid in China on the same income.

(b) Presence of employees in the host country

A double tax agreement can resolve the issue whether certain activities performed in one contracting state (country) by the employees of a company in the other contracting state, has created a taxable presence in the latter state. That is, whether the former has a permanent establishment in the latter.

Example - 2

An employee of a Japanese company is assigned to work in China continuously in connection with an engineering project of the PRC subsidiary for a period of 180 days.

There is a double tax problem, and the respective taxing rights of Japan and China are allocated in one of the following ways:

(i) As per DTA between Japan and China, the presence of employee does not create a permanent establishment in China if the following conditions are met: the employee stays in China for a period not exceeding 183 days in any 12-month period; and his income is not paid or borne by the PRC subsidiary. In this case, China does not tax the income; or

(ii) The presence of employee does create a permanent establishment in China where the parent company charges back the employee’s salaries to the PRC subsidiary. In this case, China taxes the income.

(c) Unilateral tax adjustment

Example - 3

A holding company in country A, in order to reduce its taxable income, purchases goods from its subsidiary in country B at a unit price of USD10, which is above the arm’s length price of USD6. The tax authority later adjusts the purchase price from USD10 to USD6 following the completion of a transfer pricing audit. The group as a whole will be subject to double tax of USD4 per unit of the goods sold, in the absence of a corresponding downward adjustment of the selling price for the subsidiary in country B.

To avoid the double taxation arising from a price adjustment, states may adopt article No. 9 (associated enterprise) of the OECD model tax convention, which provides that the other state shall make adjustment accordingly.

(III) Exchange of information

The exchange of information (EOI) article is provided with an aim to the prevention of fiscal evasion on income and capital, which also deals with double non-taxation of income that arises from the interaction of domestic tax rules of two or more contracting states. Specifically the EOI article operates to override the personal scope (Article 1) and taxes covered (Article 2) as provided in the OECD Model Tax Convention.

(a) Foreseeable relevance

The tax authorities of the contracting state shall exchange such information as is foreseeably relevant for carrying out the provisions of the DTA or to the administration or enforcement of the domestic laws of the contracting states concerning taxes covered by the DTA.

The EOI article is not subject to restriction by the personal scope under Article 1. The scope of information to be exchanged shall include the information in the possession or under control of a person located in the state of the requested authority, who may or may not be the tax resident of either state.

(b) Secrecy provision

Information shall be disclosed only to persons or authorities (including courts and administrative bodies) concerned with the assessment or collection of, the enforcement or prosecution in respect of, or the determination of appeals in relation to the taxes referred to in paragraph (a).

(c) Limitation to relevance and secrecy

The relevance and secrecy provisions are subject to restriction in the following way such that there is no requirement to (i) carry out administrative measures at variance with the laws and administrative practice, (ii) supply information not obtainable under the laws or in the normal course of the administration, of that or of the other contracting state, and (iii) supply information which would disclose any trade secret or process, or information the disclosure of which would be contrary to public policy.

Notwithstanding the provisions in the preceding paragraph, the requested state should not refuse to do so even if the information is not relevant or needed in the assessment, collection or enforcement of the taxes at home. Equally, the requested state cannot decline the requesting state on ground that the information is held by banks, nominees, persons acting in an agency or fiduciary capacity, or it relates to ownership interests in a person.

(IV) Definition of a person

The scope of a person is different between the avoidance of double taxation on income and exchange of information under the DTA articles. A person for purposes of (I) and (II) includes a natural persons and legal persons, who are the residents of one or both contracting states. A person for purpose of (III) includes the taxpayers and non-taxpayers, who reside or are present in the state of the requested authority.

| Content provided by |

|

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Update on the Hong Kong-Germany Double Taxation Agreement

We were recently invited to a high level discussion on the planned Double Taxation Agreement (DTA) between Hong Kong and Germany, an important topic for many of our readers. Organised by the German Consulate General in Hong Kong, the event brought together a hand-selected group of business leaders, representing German companies’ interests, and representatives of the German Federal Ministry of Finance. The aim of this meeting was to create an open forum for ideas exchange and feedback relating to the pending DTA. In particular, it was an opportunity to share with the Federal Ministry of Finance any concerns or advice that German companies may have regarding the DTA.

History

Hong Kong already has comprehensive DTAs in place with 32 countries, including Austria and Switzerland. A first round of discussions began in early 2014 to put in place a full-fledged DTA with Germany. The second round of negotiations are concluding today in Hong Kong and if successful, will still be subject to ratification. According to the German Federal Ministry of Finance, the aim of the DTA between Hong Kong and Germany is two-fold: “desiring to further develop their economic relationship, to enhance their cooperation in tax matters and to ensure an effective and appropriate collection of tax,…” and “intending to allocate their respective taxation rights in a way that avoids both double taxation as well as non-taxation...”

What the DTA means for German businesses

- Since several other major European countries have already signed a DTA with Hong Kong, Germany is currently at a disadvantage. Moreover, for Hong Kong to remain a competitive location vis-à-vis other countries such as Singapore, which already have agreements in place with Germany, a DTA would be beneficial.

- A DTA would help with cross-border tax transparency for German citizens with assets at home and abroad.

- In our opinion, a DTA with Germany would only strengthen Hong Kong’s standing as an attractive city for German businesses and individuals. Hong Kong is the gateway to China and Asia, offering a low tax regime, access to international capital markets, and its status as a RMB and transport hub. This, in combination with its sound rule of law and stable financial system, gives the city a distinct advantage over others. A DTA with Germany will only reinforce this standing.

| Content provided by |

|

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Effects of CNH Exchange Rate on Offshore RMB Interest Rate

Since November 2014, the exchange rate of offshore RMB to USD (CNH exchange rate) has depreciated while choppy CNH HIBOR led to a significant increase in capital cost. This article will discuss whether this phase of RMB interest rate fluctuation has a causal relationship with the depreciation of RMB and the dynamics of such relationship.

Effects of different sources of funds in offshore markets on RMB interest rates

Interest rate is the cost paid by those who demand capital. Hence, in order to answer the first question, we have to understand the channels for obtaining RMB capital in the offshore market and their impact on interest rates.

Unlike onshore parties who gain liquidity mainly from repurchase agreement (Repo) and the interbank market, parties in the offshore market gained RMB liquidity from the following three ways, namely, CNH swaps, interbank lending and CNH CCS. These three channels have different impacts on offshore RMB interest rates.

CNH swap refers to the use of foreign currency (mainly USD) to swap with RMB, which is similar to using USD as collateral for RMB loans. Currently, RMB swaps average approximately USD 20 billion in daily trading volume, much higher than that of interbank lending (on average USD 5-8 billion per day), and are the main channel for obtaining capital in the offshore RMB market. The “CNH Implied Yield” from CNH swap trading has also become the unofficial benchmark rate in the offshore RMB market.

Interbank lending requires the lender to pre-approve a credit line to the borrower in advance. Since such lending is essentially unsecured loans, there are certain requirements for participating institutions, limiting the capital pool available for interbank lending. Therefore, interbank lending is not as active as CNH swaps. One should also note that the quotations of offshore interbank lending are calculated mainly using CNH Implied Yields of the corresponding tenor. Therefore, price changes in offshore RMB capital will first be reflected in CNH Implied Yield and then be transmitted to interbank lending rates. As shown in the diagram below, CNH Implied Yield and CNH HIBOR Fixing are closely correlated, but the latter one is a bit less choppy as it is merely a daily fixing rate and does not represent actual market transactions.

To view the full article, please go to page top to download the PDF version.

| Content provided by |

|

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Mergers and acquisitions: Cultural alignment for successful integration

Cultural alignment is a prerequisite, opportunity, and challenge for directors and CFOs to create value and synergies in post-merger integration

Too often companies put together matches look great on paper but are fraught with management and structural problems that end up turning deals into busts. Acquiring companies often underestimate the problems that unalike company cultures can inflict on a merger. In fact, the difference between success and failure of deal-making is often not a matter of strategy or money, but rather of relationships, culture and politics.

Putting two companies together normally gives the combined entity the resources and capabilities to compete with the market giants. It would also create dominant positions in many markets around the world. However, that was not the case for advertising giants Publicis Groupe SA and Omnicom Group Inc. After the merger, the two CEOs, Publicis’s Maurice Lévy and Omnicom’s John Wren, agreed to be co-CEOs for 30 months; while that sounded good, the reality was that they couldn’t agree on a management team, the way of splitting their duties, or even on which firm should be listed as the acquirer from an accounting perspective. The deal was eventually scuttled in 2003.

The challenge of putting the companies together can be further exacerbated if the two companies have vastly different business models and cultures. For example, in Valeant Pharmaceuticals’s long-running hostile takeover campaign of Allergan Inc., the Botox-maker, the company executives of Allergan have expressed their disagreement with Valeant’s proposal to slash the amount of money that the company spends on research, a move that would probably lead to layoffs of hundreds or even thousands of its employees. As such, Allergan has disregarded Valeant Pharmaceuticals’s proposal and instead, agreed to be sold to generic pharmaceutical manufacturer Actavis plc., a company that shares similar values.

How cultural issues affect the success of an M&A transaction

Integration can be defined in general terms as the process of combining two companies into one entity at every level. Post-merger integration, the most often-cited concern that could significantly impact the success of an M&A transaction, is the top concern for directors and CFOs. Post-merger integration has to be multi-dimensional, with inputs from various perspectives, including strategy, new management, organisation, business, finance and accounting, tax and legislation, information system, and human resources. Yet, studies have pointed out that plenty of M&A transactions fail to yield desired expectations or even erode shareholder value. The little secret about M&As is that the human dimensions and culture are at least as important, if not more critical, than the strategy, pricing, and positioning. Cultural unfitness is commonly found to have a direct and indirect linkage to integration failure. Unsuccessful cultural integration could lead to organisation distractions, loss of key talents, and failure to achieve critical milestones or synergies.

Cultural integration is the key to a successful merger

Many studies agree that cultural alignment is critical to a successful merger. Yet, due to the intangible nature of culture and time constraints, management would rather focus on things that are tangible and measurable, such as financial data and legal matters. Cultural integration is then left unattended and postponed to the post-deal phase. Nevertheless, culture is not something that can be changed or integrated without well-organised plans; it requires time and attention to bring two cultures together and blend into a new collaborative environment.

Approaches to cultural integration

So, how can two different cultures be integrated to achieve full value? First of all, we have to understand the term ‘culture’. Corporate culture is the beliefs and behaviours that determine how a company’s management and employees interact and handle outside business transactions. Often, corporate culture is implied, not expressly defined, which develops organically over time from the cumulative traits of the people that the company hires. A company’s culture can be reflected in its dress code, business hours, office setup, employee benefits, turnover, hiring decisions, client satisfaction and other operational aspects. No companies are cultural twins and thus careful attention is required in understanding the cultures of both merging companies and managing the cultural integration process.

Having said that, it is highly recommended to start the cultural assessment early and make sure that the human dimensions of the combination are incorporated into your due diligence and integration planning from the beginning, instead of an afterthought. Organisations can start with cultural assessment during the due diligence stage, which provides preliminary indications on cultural alignment or misalignment of the two merging companies and whether the existing cultures can be aligned with the overall business strategy. With the cultural and strategic alignment assessments, organisations can reach a tailored sale and purchase agreement and formulate integration strategies that facilitate smoother transition and more effective integration to capture post-merger synergies. The time spent on cultural assessment needs not to be long but should be good enough to obtain a basic understanding on the cultural and strategic background of both companies.

Second, more time should be spent on development and management of the action plan. Due to its intangible nature, culture-related issues are likely to be unpredictable and thus addressing the issues can be a challenging task for the management. In most M&A transactions, companies focusing on cultural integration tend to achieve post-merger synergies – apart from analysis of cultural differences, those companies also evaluate the cultural opportunities and obstacles, which guide their efforts to the right directions. The companies would also take initiatives in redesigning the organisational structure, determining leadership assignment, and modifying human resources practices such as compensation and benefits.

This is followed by communication to employees regarding the company’s new directions and meaning of the changes. Changes may create frustration and stress to employees, yet proper communication from management with a clear vision for the integration can relieve scepticism and doubt. Accompanying with employees retention strategies and other team building activities, companies can establish a new culture and concentrate on the post-merger business goals.

Potential value of cultural alignment

“People are valuable assets to an organisation and play an integral part to the success of a business. Effective people management is the key to achieving post-merger synergies so as to maximize the optimal outcome,” says Barry Tong, Transaction Advisory Services Partner of Grant Thornton Hong Kong. As cultural integration is one of the key factors of a successful merger, it is important to have a dedicated team to manage and oversee the whole integration process.

The causes of merger failure can be complex and varied case-by-case, and there is no perfect model to apply. Nonetheless, culture misalignment is commonly considered as a direct and indirect hurdle and mismanagement of any cultural unfitness can hinder the company from realizing synergies during the integration process. Cultural and strategic alignment, active management of cultural integration, as well as proper communication between management and employees, are the suggested measures that ensure smooth cultural integration and contribute to a successful merger.

Conclusion

Cultural compatibility can have significant impact on the ultimate success of an M&A transaction. It is suggested that a separate cultural integration plan be studied, created and worked upon in the early stages of a merger. Proper management of cultural issues is the key to realise successful post-merger integration, especially from a people perspective.

| Content provided by |

|

Editor's picks

Trending articles

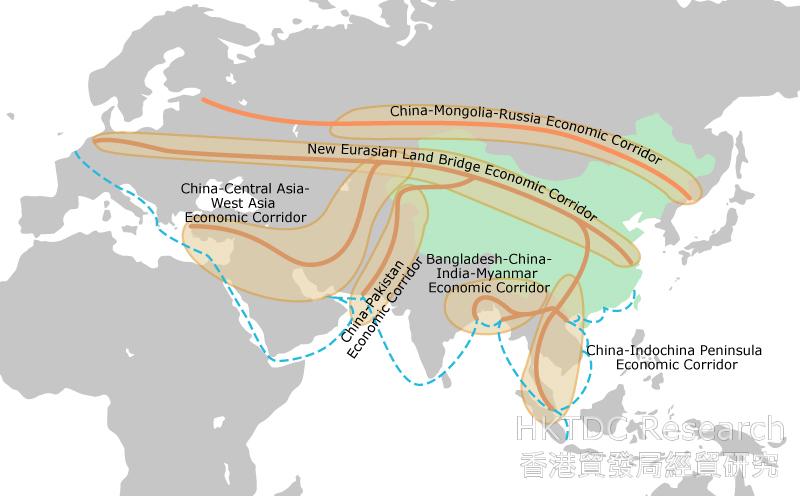

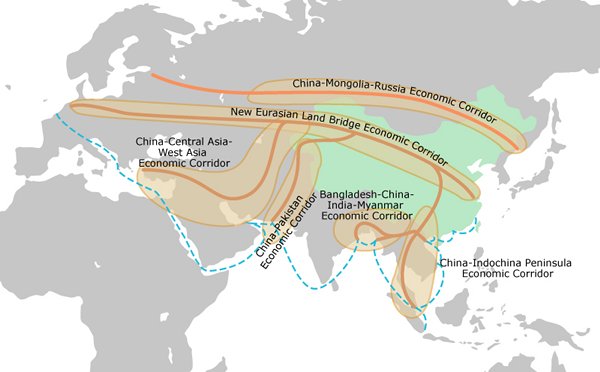

"One Belt, One Road" Initiative: The Implications for Hong Kong

The “One Belt, One Road” Initiative – the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road – is key part of China’s development strategy. The Vision and Actions on Jointly Building the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (the “Vision and Actions”) issued by the National Development and Reform Commission on 28 March 2015 outlines the initiative’s framework, co-operation priorities and co-operation mechanisms.

The Belt and Road Initiative aims to promote connectivity in infrastructure, resources development, industrial co-operation, financial integration and other fields along the Belt and Road countries. These strategic objectives are also closely connected to the “going out” strategy of many Chinese businesses. In light of the Vision and Actions document, as well as other related information sources, the “One Belt, One Road” initiative, with its extensive reach across a number of regions, represent clear development opportunities for Hong Kong.

Vision and Actions: The Key Points

The “One Belt, One Road” initiative aims to promote “connectivity in five respects”: policy co-ordination, facilities connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration and people-to-people bonds. These may be summed up as follows:

The Silk Road Economic Belt focuses on bringing together China, Central Asia, Russia and Europe (the Baltic); linking China with the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean Sea through Central Asia and West Asia; and connecting China with Southeast Asia, South Asia and the Indian Ocean. The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road is designed to go from China’s coast to Europe through the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean and from China’s coast through the South China Sea to the South Pacific. On land, the initiative will take advantage of international transport routes, rely on core cities along the Belt and Road, and use key economic and trade zones and industrial parks as co-operative platforms. At sea, it will focus on jointly building smooth, secure and efficient transport routes, connecting major seaports along the Belt and Road.

Facilities connectivity: Priority will be given to removing transport bottlenecks and promoting port infrastructure construction and co-operation in order to deliver international transport facilitation. Priority will also be given to the construction of regional communications trunk lines and networks in order to improve international communications connectivity.

Economic Corridors of the “One Belt, One Road”

Investment and trade co-operation: Efforts will be made to resolve the problems of investment and trade facilitation; hold discussions on opening free trade zones; expand traditional trade and develop modern service trade and cross-border e-commerce; promote trade through investment, strengthen co-operation with relevant countries in industrial chains, promote upstream-downstream and related industries to develop in concert, and build overseas economic and trade co-operation zones; and encourage Chinese enterprises to participate in infrastructure construction and make industrial investments in countries along the Belt and Road.

Financial integration: Efforts will be made to promote the development of the bond market in Asia and push forward the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the BRICS New Development Bank and the Silk Road Fund; support the efforts of Belt and Road countries and their companies/financial institutions in issuing RMB bonds in China; encourage Chinese financial institutions and companies to issue bonds denominated in both RMB and foreign currencies outside China; give full play to the role of the Silk Road Fund and that of sovereign wealth funds of the Belt and Road countries, and encourage commercial equity investment funds and private funds to participate in the construction of the key projects of the initiative.

People-to-people bonds: Efforts will be made to strengthen educational and cultural co-operation, including cross-nation student and education exchanges; enhance co-operation in tourism; and support think tanks in the Belt and Road countries to jointly conduct research and hold forums.

Fully leverage the comparative advantages of various regions in China:

Northwestern and northeastern regions: The initiative will give full scope to Xinjiang’s geographical advantages and make it a core area on the Silk Road Economic Belt, while giving full scope to the advantages of Inner Mongolia and Heilongjiang province with regard to their proximity to Russia and Mongolia, as well as improving the rail links connecting Heilongjiang with Russia.

Southwestern region: The initiative will give full play to the unique advantages of Guangxi and Yunnan, speed up the opening up and development of the Beibu Gulf Economic Zone and the Zhujiang-Xijiang Economic Zone (also known as the Pearl River-Xijiang Economic Zone), and develop a new focus for economic co-operation in the Greater Mekong Sub-region.

Coastal regions and Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan: The initiative will support the Fujian province in becoming a core area of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road; give full scope to the roles of Qianhai (Shenzhen), Nansha (Guangzhou), Hengqin (Zhuhai) and other locations in opening up and co-operation, and will help to build the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Big Bay Area; will strengthen port construction in a number of coastal cities, such as Shanghai, Tianjin, Ningbo-Zhoushan, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Zhanjiang, Shantou, Qingdao, Yantai, Dalian, Fuzhou, Xiamen, Quanzhou and Haikou, and will strengthen the functions of several international hub airports, notably Shanghai and Guangzhou.

Inland regions: With a focus on city clusters along the middle reaches of the Yangtze River and around Chengdu and Chongqing, the initiative will establish Chongqing as an important pivot for developing and opening up the western region, while making Chengdu, Xian and Zhengzhou leading areas for opening up in the inland regions, and developing railway transportation in the China-Europe corridor.

Co-operation mechanisms and platforms: The initiative will make full use of existing multilateral co-operation mechanisms, such as the Shanghai Co-operation Organisation (SCO), ASEAN Plus China (10+1), Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation (APEC), Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM). In addition to existing forums and exhibitions, it is also proposed that an international summit forum on the Belt and Road Initiative should be established.

Infrastructure: Taking Precedence in the “One Belt, One Road” Initiative

The Asian Development Bank estimated that the Asian economies would need to invest US$8 trillion in infrastructure to bring their facilities up to average world standards between 2010 and 2020. According to reports, China is conducting feasibility studies on four outbound high-speed railways, including the Europe-Asia high-speed rail, the Central Asia high-speed rail, the Pan-Asia high-speed rail and the China-Russia-America-Canada line. The domestic sections of the first three projects are reportedly underway, while negotiations are still being carried out on the last project, as well as on the overseas sections of the first three projects.

Apart from railway networks, other cross-border projects and the building of port facilities, airports, highways, and even electricity and communications projects in the Belt and Road countries are also targets for China’s “going out” funds. In addition to investment, there will also be a considerable number of opportunities for the international contracting of construction and machinery exports.

Industrial Co-operation: Stimulating Trade Flows

In terms of resource development, several provinces in China are planning to take advantage of the Belt and Road Initiative in order to encourage competitive industries to go global and undertake co-operation in advanced technologies. Chinese enterprises are also being encouraged to increase overseas investment in the exploitation of mineral resources in order to improve China’s supply of energy resources.

According to the Department of Outward Investment and Economic Co-operation of the Ministry of Commerce, China has established 118 economic and trade co-operation zones in 50 countries around the world. (These are set up in the host countries, with Chinese enterprises forming the mainstay based on the market situation, the investment environment, and the host government’s policies when it comes to managing investment to attract enterprises to set up production there.) Of these zones, 77 are established in 23 countries along the Belt and Road. These overseas economic and trade co-operation zones have become China’s platforms for overseas investment co-operation, as well as platforms for the clustering of industries.

There are 35 co-operation zones in countries along the Silk Road Economic Belt, including Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Russia, Belarus, Hungary, Romania and Serbia. There are also countless economic and trade co-operation zones along the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. There are, for example, Chinese industrial parks in Laos, Myanmar, Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia, and in South Asia, as well as even in Pakistan, India and Sri Lanka. The Belt and Road Initiative, then, will generate more development opportunities, including the building of industrial parks, facilitating investment projects and boosting international trade by the private sector.

Supporting Development Through Financial Co-operation

In order to provide financial support for the development of the Belt and Road Initiative, China is actively promoting the establishment of the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank, the BRICS New Development Bank and the Silk Road Fund. The Silk Road Fund was officially established at the end of December 2014. According to Silk Road Fund chair, Jin Qi, the fund will mainly invest in infrastructure, energy development, and industrial and financial co-operation, and will support the export of high-end technologies and production capacity. The Belt and Road Initiative does not have strict geographical boundaries and the fund will participate in any project relating to connectivity.

The Silk Road Fund may set up sub-funds for investment in particular industries. Some of these sub-funds may have particular industries as entry points. For example, an electricity sub-fund may be established as many companies may choose to invest in electricity projects. Another sub-fund may target particular regions. Where there are enough qualified people well familiar with a particular region, a sub-fund may be established for that region.

According to Zhou Xiaochuan, Governor of the People’s Bank of China, the Belt and Road Initiative will generate development and investment opportunities as it has diverse financing needs, with the role of the investment bank being to match investment demand and supply through proper financial arrangements. In terms of the demand for qualified personnel, Zhou said that staff members must have experience in investment and international exposure, in addition to a sound understanding of particular countries. They must also have expertise and social connections, together with an engineering background (especially in financing for engineering projects), possess considerable knowledge or experience in key industries, and speak a relevant foreign language.

Driving Increased Levels of Domestic Investment

Chinese provinces are responding positively to the Belt and Road Initiative. According to reports, as of 5 February 2015, more than two-thirds of the 28 mainland provinces that had held their local people’s congresses and political consultative conferences have made their own plans for the initiative. In infrastructure planning, for instance, Chongqing has issued its Opinions on Implementing the Belt and Road Strategy and Building the Yangtze Economic Belt and is expected to invest Rmb1.2 trillion in infrastructure before 2020. This will generate opportunities for co-operation in construction, planning, management, finance and other related fields.

Implications for Hong Kong

In terms of industry sector, infrastructure may be the first stage in the development of the Belt and Road Initiative. It requires investment, project contracting and will drive demand for relevant services. In this connection, Hong Kong should be able to find a considerable array of opportunities in financing, project risk/quality management, infrastructure and real estate services (IRES), as well as several other related fields.

A number of Chinese enterprises may become involved in mergers and acquisitions in the course of “going out”. According to some analysts, China’s aviation industry should also plan to “go out” through mergers and acquisitions. To date, Hong Kong has been the key platform for the mainland’s outward investment. By the end of 2013, Hong Kong accounted for 57.1% of China’s outward investment stock, with the cumulative value standing at US$377.1 billion. The increase of investment and merger and acquisition activities will increase the demand for the respective professional services in Hong Kong.

The launch of the Belt and Road Initiative will increase people-to-people exchanges between China and the countries concerned, as well as boost demand for international logistics. Hong Kong has a leading edge in global logistics links and operation. In addition to freight services, Hong Kong can give further leverage to its functions as a maritime services centre. As Nansha in the Guangdong Free Trade Zone also intends to develop maritime services, Hong Kong may explore co-operation possibilities with the district.

Another area in which Hong Kong can play a substantial role is financial services. Hong Kong can provide additional services here, including fund raising, financing, bonds, asset management, insurance and offshore RMB business. Hong Kong can also seek to play a bigger role in the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, BRICS New Development Bank and Silk Road Fund, including encouraging these institutions to set up their headquarters and branches in the territory and make greater use of Hong Kong’s international talent, as well as inviting the Silk Road Fund to set up sub-funds in Hong Kong. In addition, passenger and freight transport, aircraft leasing and other aviation-related financial services also represent a considerable number of opportunities.

In terms of industrial co-operation, China’s overseas economic and trade co-operation zones will become platforms for overseas investment and co-operation for Chinese enterprises, as well as platforms for the clustering of industries. Southeast Asia, South Asia and Central Asia may further develop into a more extensive network of bases for industrial relocation and even open up as consumer markets. The demand for logistics, supply chain management, consumer products and services may increase with the growth of these regions. Following the opening of logistics hubs in Central Asia, there will be railways linking China with the region. For example, Hong Kong businesses may consider using the Chongqing-Xinjiang-Europe railway to transport goods directly from Chongqing to the Central Asian market, thus saving time and money.

With regard to regional development, apart from Southeast Asia, South Asia, and even Central Asia, Central and Eastern Europe, the demand of mainland provinces for infrastructure investment and logistics services in support of the Belt and Road Initiative will also generate business opportunities for the relevant industries.

Hong Kong can also play a more proactive role in the Belt and Road co-operation platform. For example, Hong Kong may strive to regularly host international summits/forums and work with think tanks and cultural and educational institutions in the Belt and Road countries in conducting research, training, co-operations and exchanges. It could also act as a platform for personnel exchanges/training in relevant fields, such as logistics, infrastructure and finance.

| Content provided by |

|

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Made in China: Sourcing in the “New Normal”

Finding the Right Balance

VF is a USD 12 billion apparel and footwear powerhouse, with an incredibly diverse, international portfolio of brands and products, including The North Face, Nautica, Timberland, Vans, and more. VF has sourcing relationships with more than 1,000 product manufacturing facilities in Asia-Pacific region countries, including China, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand, Cambodia, Pakistan, and India.

China Focus interviews Veit Geise, VP Sourcing of VF, on his opinion of China as a sourcing destination and what trends and challenges to expect when operating there.

How important is China for you compared to other production countries?

This largely depends on the brands and whether we are looking at export or at Chinafor-China business. Price-sensitive brands continue to move or have already moved their activities to other countries several years ago, while very technical brands with a complicated outerwear segment, for example, still depend on China to a large extend. Growing sales & marketing activities in China continue to result in an increase of the Chinafor-China volume, which compensates for a loss of export volume. China, therefore, will continue to be one of the most important sourcing destinations in the future.

What factors do you consider when deciding to stay or move your production location?

This, too, depends on the brands that you are looking at. A price-sensitive business will react very fast to labour cost increases or a change in the geopolitical environment. The more technical a brand is, the less you will be inclined to move volumes to other areas for small incentives. A supplier who understands the complexity and DNA of a technically complex brand, is worth a lot more than saving a few pennies by moving countries. Nonetheless, depending on the product, a supplier’s readiness to react and adapt to changes is critical.

Is price the only factor for your customers?

Definitely not, although it is clearly a driver for making sourcing decisions. Gross margin pressure will not become less in the future, and with inflation at the sourcing locations and little chances to increase retail prices in general, the price pressure will not go away. It is the right balance and mix that you need to find and manage for each brand individually.

What are the challenges you face now in China and beyond? How do you overcome them?

The sourcing business has become much more complex over the past years, and we can anticipate even more complexity in the years to come. Today we require a much greater level of transparency from our factories than we have done in the past. CSR requirements, as well as responsible sourcing, have become very important factors in a relationship. The only way to build successful alliances in the future is an even closer partnership between the buyer and the seller. We will continue to see a further decline of purely transactional business.

To view the full article, please go to page top to download the PDF version.

| Content provided by |

|

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Grant Thornton: Growing Appetite for M&A in China

According to the recent Grant Thornton International Business Report (IBR), China mainland businesses’ appetite for M&A activity continuously grows and the M&A market sets to grow further over the next 12 months. Businesses' M&A plans are becoming more focused as the quality of available targets improves and the willingness of potential vendors to contemplate a sale increased.

M&A activity forecast in China for 2015 up of 10%

“To buy” and “to sell” are key elements for a successful M&A market. The IBR reveals that the year of 2014 witnessed an active M&A market in China. 26% of business leaders seriously considered at least one acquisition opportunity, up from 10% in 2013. Meanwhile, the M&A activity forecast for 2015 increased to 20%, a rise from 10% over the past year. While the willingness of potential vendors grows, the percentage of businesses planning to sell up is also on the rise. The proportion of businesses expecting a change in ownership in the next three years rose from 6% to 9% over the past year.

Confidence in the ability to fund transactions is vital for an active M&A market. Whilst retained earnings (52%) remain a significant source of funding, the proportion of businesses planning to use bank debt to finance deals has risen to 51% from 22% in the last year. The percentage of businesses expecting to finance growth through private equity also increased from 8% to 24%. Meanwhile, despite of the recovery of IPO market, China has seen no increase in the businesses planning to finance deals through public listing (14%).

Xu Hua, CEO of Grant Thornton China, says, “The year of 2014 witnessed an M&A boom. Both the number and the total volume of transaction broke a new record. With the further reform of state-owned enterprises and businesses’ increasing ‘going out’, China’s domestic and overseas M&A markets are both expected to be more active in 2015. CBRC issued the revised edition of Guidelines for Risk Management by Commercial Banks of Loans Extended for Mergers and Acquisitions, easing some M&A financing restrictions which had troubled businesses. This benefits the businesses which starve for financial support for M&A activities.”

The greatest appetite for acquisition in North America

From a global perspective, the IBR reveals that 33% of businesses are planning to grow through M&A over the next three years, a steady rise from 31% in 2013. North American business leaders remain the most bullish (45%), ahead of Latin America (38%), Europe (32%) and Asia Pacific (22%). Meanwhile, 43% of business leaders seriously considered at least one acquisition opportunity over the past 12 months, up from 39% in the previous period. The proportion of businesses expecting a change in ownership in the next three years rose from 11% to 14% over the past year. Finland (38%) is the most bullish for sell, followed by Latvia (32%) and South Africa (29%).

Regarding to different sectors , mining & quarrying industry is the most bullish industry with 60% of businesses planning acquisition in the next three years, ahead of financial service (53%), electricity, gas & water supply (53%), and agriculture, hunting, forestry and fishing (44%). Transport is the most cautious (26%) sector.

| Content provided by |

|

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors | 8 May 2015

RICS Singapore Commercial Property Monitor Q1 2015

Flat market but prime office still expected to post gains

Key macroeconomic trends

The economy grew by 2.1% on a year-on-year basis in Q1 due at least in part, to stronger growth in construction activities and service sector businesses. The bad news is that faced with continued global instability, the performance of the manufacturing sector has been quite disappointing. Singapore’s manufacturers recorded a fourth straight monthly drop in output in March. Moving in tandem with the PMI trend, industrial production figures in January and February decreased by 1.2% year-on-year partly as a result of the weak demand for electrical products abroad. Interestingly, weak manufacturing activity has continued to weigh on the industrial property market. Manufacturers have been reluctant to increase the size of space occupied. According to the Q1 RICS survey, this has contributed to the industrial rental outlook remaining quite gloomy. Meanwhile, we expect a slight pick-up in GDP growth in 2015 and this reflects the expectation of a gradual improvement in economic activity.

Occupier Market

- The Occupier Sentiment Index remained in broadly neutral territory at +2 which signals little change occurred over Q1.

- Tenant demand picked up fairly strongly in the office sector but remained flat in the retail area of the market. Meanwhile the industrial sector experienced a modest decline.

- Alongside this, supply of leasable space increased further in all areas of the market in Q1.

- Near term rent expectations remained flat in general but saw a more material downturn in the industrial sector (-27). The twelve month view has a broadly similar pattern with rents in aggregate projected to rise by 1.4%.

Investment Market

- The Investment Sentiment Index remains in negative territory albeit a little less so, at -9, than in the preceding quarter.

- Investment enquiries improved significantly in the office sector. Meanwhile, they continue to fall in the industrial and retail areas of the market, albeit at a slower pace than previously.

- This was broadly mirrored in the attitude of foreign buyers.

- The supply of commercial property for sale picked up quite notably within each market segment.

- Capital values are anticipated to rise further in the office sector but dip in the retail and industrial sectors over the next twelve months.

- The aggregate increase over the period is projected at 0.3%, but prime office space is expected to record growth of 9.5%.

To view the full article, please go to page top to download the PDF version.

| Content provided by |  |

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Bank of China (Hong Kong) | 25 May 2015

Headwind? Tailwind!Examining the Direct Impacts of the RMB’s Possible Inclusion into the SDR

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) unofficially begins its quintuple review of the SDR basket in recent days, with official result to be expected in October, and implementation at the beginning of 2016. Taking into account of the progress made by the RMB in the past several years including the RMB’s use in cross border trade settlement, investment and reserve assets, its approaching the freely usable standard argues strongly for its inclusion into the SDR this time around. The market is generally optimistic about odds of this outcome because it is a matter of when not if. If successful, it will have direct implications to the RMB internationalization in terms of its policy and market drivers.

I. The RMB meets the basic requirements

IMF generally conducts review of its SDR currencies basket every five years. During the last review in 2010, the RMB was the only candidate being seriously considered for inclusion. China already met IMF’s first criterion at that time, with its exports of goods and services during the five-year period ending 12 months before the effective date of the revision having the largest value. In 2010, China was the world’s third largest exporter of goods and services. Since then, China continues to make headways. Its foreign trade totaled RMB25.42 trillion in 2012, second in the world, and RMB25.83 trillion in 2013, surpassing that of the US to lead the world. In 2014, China retained the crown with foreign trade totaling RMB26.43 trillion. In 2014, China’s GDP reached USD10.38 trillion, second only to the US. In the meantime, the foreign direct investment (FDI) China attracts is also second only to the US, and China’s outbound direct investment (ODI) is right behind Japan and the US amongst G20. The dollar amount has been basically at par with that of FDI. China’s real economy, especially trade and investment growth, sets a solid foundation for the RMB to qualify for the SDR. It is not unreasonable to claim that the RMB internationalization is lagging behind China’s economic clout.

The second criterion is that it has to be determined by the IMF under Article XXX (f) to be a freely usable (FU) currency, which concerns the actual international use and trading of currencies. To help make the decision, the IMF refers to four quantitative indicators: the Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) complied by the IMF itself, the international banking liabilities compiled by the Bank of International Settlements (BIS), the international debt securities statistics also compiled by BIS, and the global forex markets turnovers captured by BIS’ Triennial Central Bank Survey.

Overall, the RMB’s strength lies in offshore deposits and forex trading. In 2014, offshore RMB deposits amounted to RMB2.8 trillion or USD440 billion, making it the fifth largest currency right behind the four SDR currencies. And based on the global forex markets turnovers captured by BIS’ Triennial Central Bank Survey, the RMB is ranked the ninth with a market share of 2.2/200. At the end of 2014, it was the sixth most actively traded currency.

The RMB’s weakness is in central banks holdings and the RMB international bond market. On one hand, COFER has not been able to single out the RMB in its statistics. It was included in other currencies that accounted for 3.1% of the total in 4Q14. On the other hand, the offshore RMB bond market’s size of RMB480 billion at the end of 2014 results in a small share of 0.4% of the total.

It is worth noticing that of these four indicators, three are linked to the offshore market, showcasing the importance of the offshore RMB market’s development to its SDR ambition. Moreover, those indicators are not meant to be used mechanically. IMF also emphasizes that the Executive Board’s judgment is necessary. Combined with Christine Lagarde’s latest comment that it is a matter of when, not if, the RMB makes it into the SDR, and the RMB internationalization’s progress in the past several years, the RMB stands a fairly good chance to pass IMF’s internal assessment of being freely usable in this year’s review.

To view the full article, please go to page top to download the PDF version.

| Content provided by |  |