Chinese Mainland

Guangxi is strategically located as part of China’s direct link to Southeast Asia, with a land border with Vietnam and multiple ports on its shoreline. Guangxi’s Beibu Bay is earmarked as a regional international logistics hub under the autonomous region’s 13th Five-Year Plan, as well as for vigorous development in manufacturing supply chain logistics. The industrial parks in the autonomous region have realised that in the long run they cannot rely solely on preferential policies to prosper but need to develop R&D and support services, such as raising the standards of inspection and testing, and providing training for key personnel, all of which are bound to boost the demand for logistics and professional services.

Potential of Developing Logistics Services in Guangxi

Aligning itself with the central government’s Belt and Road Initiative, Guangxi is stepping up efforts to strengthen the transport links between China’s inland and Southeast Asia, and enhance its ports’ handling capacity and links with the hinterland. It is also looking to build its capital city Nanning into an integrated transport hub. The development involves transport infrastructure as well as related logistics services. On land, according to the Guangxi Development and Reform Commission, Nanning as a regional hub will connect with the Indochina Peninsula to the south. At sea, Beibu Bay will be developed into a regional shipping centre forming part of the China-ASEAN port cities co-operation network. Ten new maritime routes have been operating since the network was established in 2013.

Guangxi is accelerating the pace of constructing a shipping-route network covering ASEAN’s port cities. There are now 35 regular container-ship routes in Beibu Bay connecting ASEAN countries including Brunei, Indonesia and Malaysia. Meanwhile, the overall planning of the entire Beibu Bay has been revised to reposition it as a mother port integrated with warehousing, multimodal transport, port industries, modern logistics, shipping services, passenger travel and international cruises. Division of labour will be carried out by the three main ports: Fangcheng will handle bulk cargo, complemented by container operations; Qinzhou will rely on its bonded port to set up international logistics and develop container and petrochemical maritime businesses; and Beihai will focus on tourism, plus some production operations.

The Guangxi government issued the Implementation Details of the Beibu Bay Economic Zone Port Logistics Development Subsidy in 2016 to attract cargo supply from the mainland and encourage relevant operators. Under the terms, subsidies of different kinds are offered to freight forwarders operating the routes or taking up contracts of sea-rail multimodal transport outside of Guangxi via Beibu Bay, and to Guangxi production enterprises making use of Beibu Bay’s newly added function for containerisation for import and export.

Guangxi is actively developing its role of connecting inland China with ASEAN countries, building more transport routes with Guangxi as the gateway. For example, cargo transport between Guangxi and Thailand has picked up since 2016. According to the Guangxi Department of Commerce, imports and exports between Guangxi and Thailand increased by 32.9% from January to November 2016, with the bulk being Thai electronic products imported through Pingxiang on land and forwarded to locations in the Yangtze River Delta, such as Suzhou. Previously, it took about 14 days to transport goods from Bangkok to Suzhou by sea, while today it only takes about six days through Guangxi by land. The full potential of logistics services in Guangxi under the Belt and Road Initiative is there to be tapped.

Better Logistics Services, at Lower Costs

The Guangxi Department of Commerce and local market players are rosy about the logistics industry in the autonomous region, especially international logistics, agricultural logistics and cross-border e-commerce. Despite rapid development in recent years, the overall market size is still small and logistics costs are high – estimated to be 3 to 4 percentage points higher than the national average. As such, Guangxi is focusing on reducing logistics costs while improving efficiency. Under the 13th Five-Year Plan for Guangxi’s logistics industry, the autonomous region will optimise its transportation structure, encourage the development of professional container and cold-chain transport, improve internal management and upgrade the service of logistics enterprises through advanced information technology, all with the aim of cutting costs.

As few large-scale logistics enterprises operate in Guangxi, and those that do are mainly state-owned, the autonomous region hopes to introduce more overseas enterprises to spur the development of local logistics services, reduce costs and increase efficiency. Sixteen modern logistics clusters are now under construction, and there are plans to promote logistics standardisation and informatisation – by way of integration to enhance efficiency and improve storage utilisation.

Room for Developing Cold-Chain Logistics

Guangxi is a large agricultural region, with a rich supply of fruits, vegetables and aquatic products. According to the Guangxi Department of Commerce, it exports about 30 million tonnes of fruits and vegetables a year, with higher volumes during winter and spring when the vegetable supply in the north is relatively small. In the mainland consumer market, not only are there high import and export volumes of agricultural products, but also higher demand for product quality. To meet this demand, Guangxi is to build an eco-friendly fruit and vegetable base supplying Shanghai, which will involve modern cold-chain logistics services to meet the higher standards of the end-user market.

However, the proportion of cold-chain circulation in Guangxi is relatively low – about 25.4%, 14.3% and 64.3% for fruits, vegetables and aquatic products, respectively. The loss ratio is higher than the national average, with fruits at about 20%, vegetables 12% and aquatic products 15%. Demand for cold-chain logistics services in Guangxi cannot be understated. In addition to the local supply, about three million tonnes of fruits and one million tonnes of aquatic products are imported from Southeast Asia via Guangxi ports every year.

Cold-chain logistics in Guangxi is littered with problems including structural imbalances. Refrigeration companies, for example, are concentrated in the central cities, with few at production bases. Services provided are relatively simple – generally just storage – with neither upstream-downstream integration in the industry chain nor advanced information platform systems. In view of this, Guangxi is working on a high-standard development plan, and is about to roll out preferential policies in support of cold-chain logistics, encourage the entry of new enterprises and establish public information service platforms to better link up with upstream and downstream sectors.

Guangxi is set to build a two-way market for fruits and vegetables, which currently transit the region from ASEAN countries and go to Guangdong for distribution or processing. Taking up the space, Guangxi hopes to develop the local distribution and foreign/domestic trade market as well as the processing industry chain.

Demand for Producer Services on the Rise

In addition to logistics services, Guangxi’s industrial structure has in recent years been gradually moving towards high value-added sectors and adding value to processing trade. In Beihai City, for example, the industry chain in Beihai Industrial Park is already extending upstream and to R&D, with five state-level high-tech enterprises and eight provincial R&D centres and technology centres established. In the long run, industrial development cannot rely on preferential policies alone but requires the development of support services, including improving the level of local testing services, standard certification services and personnel training.

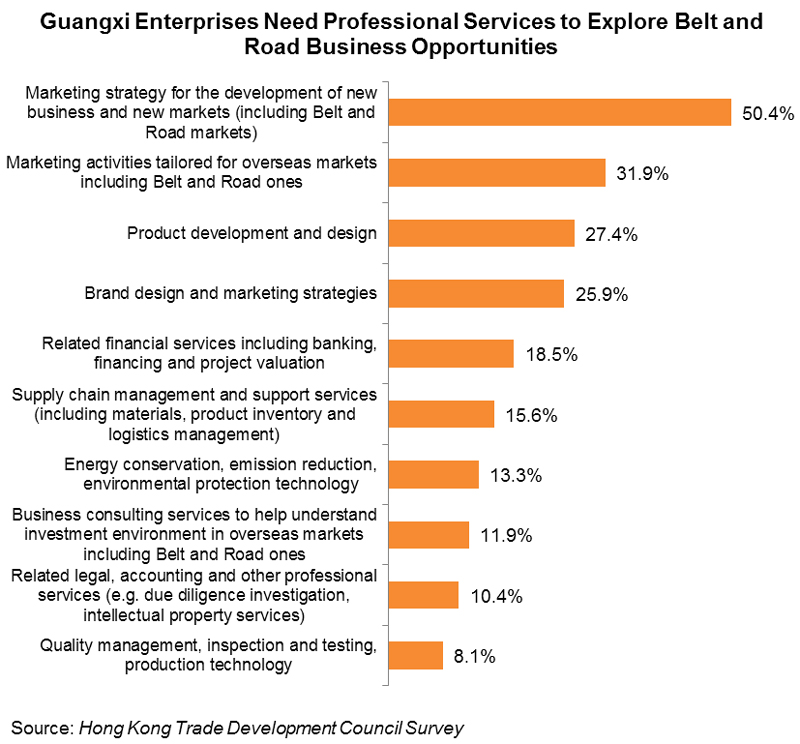

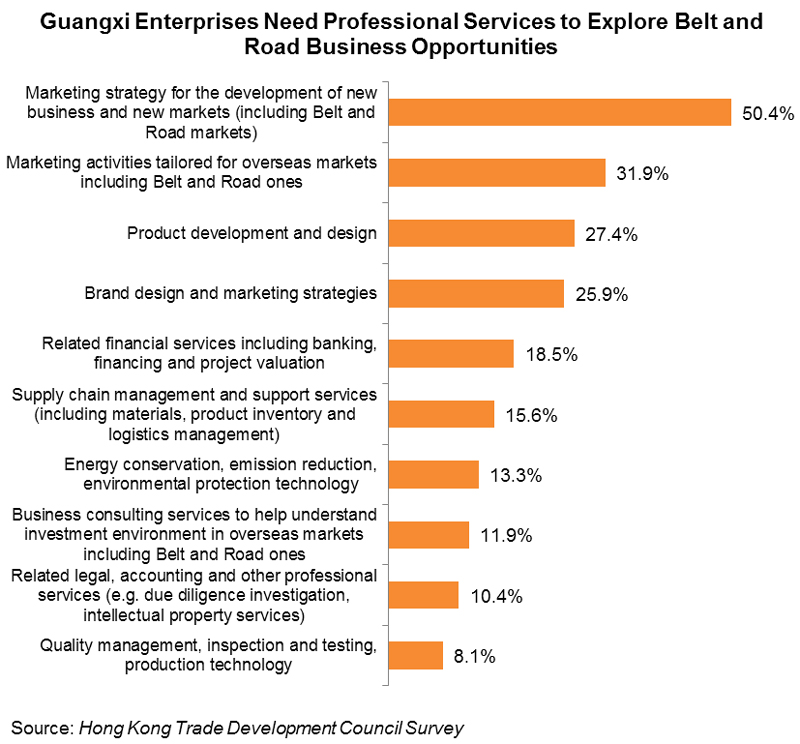

A survey was conducted by HKTDC Research on Guangxi enterprises during the China-ASEAN Expo 2016 [1] to study their tendency to explore the business opportunities brought about by the Belt and Road Initiative and their demand for professional services. In the face of market competition and challenges, most companies said they have made adjustments and investments in business and business strategy or would consider doing so within one to three years. Among the respondents, 49.3% said they would step up developing overseas markets, 29.4% would enhance product design and technology R&D capabilities, while 28.7% would choose to develop/strengthen their own branded businesses.

Many companies indicated interest in enlisting professional service support, with 50.4% of respondents saying they needed a marketing strategy for the development of new business and new markets. To tap Belt and Road business opportunities, some 27.4% wished to seek product development and design services, while 25.9% said they required brand design and promotion strategy services. To secure such professional services, 60% would first tap relevant service support on the mainland, and 53.3% would be interested in seeking professional services in Hong Kong. In conclusion, the survey shows that there is demand by Guangxi enterprises for professional services support from Hong Kong, second only to the mainland.

Guangxi enterprises are looking for professional services support to develop their business amid the growth of service outsourcing in the autonomous region. According to the Guangxi Department of Commerce, the size of the service outsourcing industry doubled in 2016. For instance, a French company opened a call centre in Nanning, a model city for service outsourcing in Guangxi, serving ASEAN customers. Indeed, Nanning as an outsourcing service base has a language advantage as many local residents with long-term contacts with Vietnam and Thailand can understand Vietnamese and Thai. At the same time, Guangxi also hopes to bring in more service outsourcing business with Hong Kong as their “super connector”.

Guangxi Actively Promoting CEPA

The Mainland and Hong Kong Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement Agreement on Trade in Services (CEPA Agreement on Trade in Services), signed between the central government and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) Government, took effect on 1 June 2016. Under the agreement, Guangxi is one of the two pilot regions for implementation of CEPA’s early and pilot measures, after Guangdong.

Guangxi is very positive on the role of the CEPA service trade agreement in carrying out service trade liberalisation between Hong Kong and the mainland. Particularly in some pilot areas– including architectural design, urban planning, landscape design, conference display, international transport and tourism – Guangxi hopes the CEPA service trade agreement can help strengthen its economic and trade links with Hong Kong, and introduce more related professional services such as efficient logistics services from the city, so as to set a new high watermark for the development of Guangxi’s industries.

A circular on the Action Plan for Implementation of the CEPA Agreement on Trade Services in Guangxi (CEPA Action Plan) was promulgated in August 2016 for a number of work plans, including the strengthening of the CEPA early and pilot measures joint conference system in Guangxi. Six task forces were set up to strengthen co-operation in and co-ordination of key areas such as finance and law, tourism and health, trade and exhibition, transport and logistics, architecture and cultural creativity, as well as processing trade industry transfer.

In an attempt to facilitate Hong Kong and Macau enterprises to make better use of CEPA’s open policy to invest in and provide professional services in Guangxi, and solve the common problem of “big door is open, small door is closed”, Guangxi has implemented numerous reforms to allow a more efficient implementation of CEPA. Following more closely the national unified approach, the autonomous region will establish a service trade investment filing system corresponding to CEPA’s negative list and set up a Guangxi CEPA Projects Green Channel in the municipal office of various cities providing one-stop government services for Hong Kong and Macau investors. It aims to help solve the specific difficulties encountered by service providers in developing the sector in Guangxi.

The CEPA Action Plan has made it clear that the various task forces will promote a number of projects as CEPA demonstration projects, with the objective of strengthening co-operation with Hong Kong in introducing professional services. According to actual needs and based on Guangxi’s own industries, the autonomous region will ask various cities to recommend a number of projects with professional services needs, forming a CEPA co-operation project bank to connect with Hong Kong professional service providers.

In addition to co-operation in processing trade between Guangxi and Hong Kong, more industries can be added into the mix, including electronics and electro-plating. Meanwhile, co-operation in the service sector is also a possibility. Given the efficient management of Hong Kong’s airport facilities, much of this expertise could be extended into the development of both Nanning’s airport and its port facilities, while cold chain logistics has particular growth potential here.

In the manufacturing sector, there are a number of large-scale enterprises in Guangxi in the electronics, automobiles and food sectors. This, coupled with the efforts made by processing trade to seek transformation and upgrading and move towards higher value-added, has generated a huge demand for such professional services as R&D, brand promotion and product testing, which the autonomous region is in dire need of. Hong Kong's service providers, well-placed to fill this gap and assist in effecting this transformation and upgrading, stand to benefit from the opportunities arising therefrom.

[1] The survey was conducted among Guangxi enterprises during the China-ASEAN Expo in September 2016 and 149 questionnaires were collected. Related content can be found at Chinese Enterprises Capturing Belt and Road Opportunities via Hong Kong: Findings of Surveys in South China.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By King & Wood Mallesons

Introduction

China’s One Belt One Road policy represents a renewed and strengthened push to connect Chinese investors with investment opportunities along the historical Silk Road trade route and a new maritime route. Whilst the increased investment by China along this route presents clear opportunities for domestic Chinese companies and their OBOR investment counter-parties the road is likely to be a bumpy one.

Challenges will be as diverse as the OBOR countries themselves which range from Singapore to Syria and contain significant divergences in operational and investment risks. However, a web of investment treaty protections overlay the route and provide a crucial means of reducing the risks involved in investment. We set out in this article the policy details, investment protections and detail some of the key considerations for OBOR investors.

Section 1 – Journeying along the bumpy OBOR superhighway

The OBOR policy, which was unveiled by Chinese leader Xi Jinping in late 2013 focuses on economic connectivity and cooperation along a pan-continental superhighway encompassing a land-based “Silk Road Economic Belt” and an ocean going “Maritime Silk Road”. The initiative promises to deepen an already active Chinese involvement in developed economies in South-East Asia on this route as well as opening up new investment in developing economies in Central and Western Asia and Africa. To stimulate this investment, the Chinese Government has pledged a sizeable amount of its own sovereign wealth including:

- USD 40 billion to establish a Silk Road Fund to focus mainly in infrastructure and resources, as well as in industrial and financial cooperation between the countries along the OBOR route; and

- USD 50 billion to a new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (the “AIIB”) which, as the name suggests, is to act as a regional fund for infrastructure projects across its now 57 members in the Asian region.

It is expected that the bulk of the funds in the Silk Road Fund and the AIIB will be spent on infrastructure, construction and energy and resources projects which will take OBOR investors along a sometimes bumpy route. Whilst the OBOR route may begin in more traditional and developed “Chinese Commonwealth” trading partners in Asia it continues through less traditional, Central and Western Asian nations such as Afghanistan, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Georgia as well as African and European nations.

Many of these countries will prove difficult territory for investors to navigate through and will pose serious operational risks. Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria continue to be beset by conflicts; Central Asian nations such as Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan contain potential political and economic risks; whereas OBOR countries from Africa and parts of Asia, continue to suffer from undeveloped legal and operational infrastructures and a lack of funding. These risks and the other legal, regulatory and sovereign risks in the countries through which the route passes militate careful planning by OBOR investors journeying along this highway.

Aside from the usual awareness of risk and prudent contracting and investment structuring, Chinese investors and their contracting partners on the OBOR route should also be aware of their rights under the web of investment treaties covering the route.

Section 2 – Investigating investor protections covering the OBOR route

More than 50 separate bilateral investment treaties (“BITs”) and several multilateral investment treaties (“MITs”) criss-cross the OBOR superhighway and provide a robust source of potential investor protections. Such protections, however, must be understood and carefully planned for by OBOR investors.

BITs and MITs are agreements between countries encouraging investment and setting out the protections each will afford each other and their investors. With the inclusion of Investor State Dispute Settlement (“ISDS”) mechanisms in these investment treaties, corporate and individual investors may be able to bring claims against OBOR governments for breaches of the substantive investor rights set out in those treaties without recourse to the host state’s domestic legal system. The independence of this process from domestic legal systems means that MIT and BIT protections are a crucial bulwark against the political and legal risks that OBOR investors are likely to face.

Arbitration mechanisms, whether under contract or treaty, are powerful rights for OBOR investors because they permit investors to enforce their rights without reliance on local procedures or diplomatic means. Notably, the usual dispute resolution method under Chinese BITs and MITs, ICSID arbitration, allows investors to rely on simplified enforcement mechanisms under the Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of Other States (the “Washington Convention”). Host states that are party to the Washington Convention are required to enforce arbitral awards made under that Convention, making enforcement of awards an international law obligation. 55 countries along the OBOR route are party to the Washington Convention and voluntary compliance is the norm, although not always the rule.

Nevertheless, concerns surrounding reputation and creditworthiness are likely to continue to encourage OBOR governments’ compliance with enforcement.

What kind of investment protections are offered under investment treaties?

Typically, the protections offered in MITs are similar to the protections offered in BITs. The scope of guaranteed protection offered by each treaty will be set by the wording of a particular treaty. Common forms of guaranteed protection include:

- compensation for expropriation or nationalization of investor’s assets by a state. Typically, this guarantee covers both direct and indirect expropriation, and additionally prohibits expropriation unless it is for a public purpose;

- fair and equitable treatment, as well as protection and security afforded to investments. Clauses setting out these protections are designed to create a standard of treatment independent of the standard of treatment afforded to domestic investments which can vary dramatically from state to state; and

- treatment of foreign investments in a manner no less favourable than that provided to domestic investments.

Even though the scope of guaranteed protections offered under each treaty is set by the wording of that particular treaty, investment treaties often also contain a Most Favoured Nation (“MFN”) clause. MFN clauses allow investments covered by a particular treaty to be afforded the same treatment that the host state would give to any other third state’s investments. This allows an OBOR investor to rely on guaranteed protections set out not only in treaties to which China and the OBOR countries are parties but potentially also any other, better substantive protections that any third party country enjoys under its treaty with the OBOR investment host state in which the investor is investing.

How to make use of investment treaties?

In order to fall within the scope of a particular treaty, the investment needs to fall within the definition of ‘investment’ under that treaty. Typically, the definition of ‘investment’ under treaties is broad and non-exhaustive, in the hopes of capturing evolving types of investments. The broad definition is often followed by a list of non-exhaustive examples such as tangible and intangible property, capital investments in local ventures (regardless of form through which they are invested), financing obligations, infrastructure contracts, etc. Often, the definition of ‘investment’ encapsulates not only the primary investment, but also its collateral elements such as loans – which may themselves be considered distinct investments. While treaty definitions of investment are often broad, each treaty may also set out requirements that an investment must comply with in order to be afforded protection under the treaty, for example: compliance with national law. The definition of investment has been subject to significant arbitral scrutiny: tribunals have found that in order to be considered an investment, the investment must assume risk and make contributions to the state, and contain a certain degree of longevity.

Depending on the scope of application of the treaty, it is possible that guaranteed protections in treaties which did not exist at the time of investment may nonetheless apply to those investments. Typically, guaranteed protections survive for a certain period of time after termination of a treaty.

It is also necessary that investors are viewed as such for the purposes of the treaty. Typically, natural and legal persons must be nationals of a contracting state in order to rely on benefits set out in a treaty, but such persons cannot be nationals of the host state. Often, the question of nationality of the investor is difficult to answer when complex holding structures are used to invest. Under some treaties, place of incorporation is relevant whereas under other treaties, the place from which substantial control of the investments is directed determines who the investor is, and accordingly what is the investor’s nationality.

OBOR investors therefore need to be aware not only of the existence of BIT/MIT rights but the impact that structuring an investment on the OBOR route can have on the protections available to them.

Section 3 –MIT/BIT planning on the OBOR route

1. Know your treaty rights: forewarned is forearmed on the OBOR superhighway and OBOR investors should carefully check the BITs and MITs between China and the OBOR country where an investment is being made and their specific provisions. OBOR investors should also check that any treaties are still in force and verify the OBOR country’s history in dealing with ISDS claims.

For example, although a Chinese company seeking to benefit from OBOR investment might consider taking advantage of the China-Jordan BIT, which incorporates a fair and equitable treatment and no expropriation without due compensation clauses, as of the date of writing that treaty is not in force. OBOR investors from Chinese Special Administrative Regions, Hong Kong and Macau should take care to ensure that their residency in an SAR qualifies them as a “national” of China for the purposes of any treaty. Although a Hong Kong investor has already successfully brought a case before ICSID as a Chinese “national” on the basis of the China-Peru BIT some treaties expressly exclude the SAR territories from treaty definitions.

Finally, careful attention should be paid to an OBOR government’s attitudes to ISDS: an OBOR investor in Poland would be prudent to take heed of its government’s recent pronouncement that it is considering cancelling all of its BITs and an OBOR investor in Russia might consider the fraught recent history Russia has had with enforcing treaty claims against it.

2. Contracting for treaty rights: to the extent possible, drafting of contracts governing the investment should: (i) set out the parties’ intention that OBOR investors and their investment vehicles are understood to be “nationals” for the purpose of the relevant treaties which apply; (ii) make it clear that the investment itself is agreed to be an “investment” for the purposes of the contract. Similarly, where contracting or dealing directly with OBOR governments, ISDS clauses of relevant BITs and MITs should additionally be incorporated into contracts to ensure that the host state is contractually obliged to comply with any specific treaty obligations.

3. Consider structuring an investment to take advantage of OBOR ISDS: OBOR investors should consider structuring or restructuring their investments to ensure that they qualify for ISDS protections. When structuring investments, parties ought to give similar weight to considerations regarding ISDS and falling within the scope of investment treaty protections, as they do to the usual tax, funding and corporate governance considerations.

Please click to read the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Balbina Y. Hwang, Visiting Professor at Georgetown University in Washington D.C.

Abstract

In 2013, two countries in East Asia launched their respective visions for an East-meets-West integrated region: China pronounced one of the most ambitious foreign economic strategies in modern times by any country, “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR), and South Korea launched the “Eurasia Initiative” (EAI). This paper examines the rationale, contours, implications, and possibilities for success of Korea’s EAI within the context of China’s OBOR, because a study of the former is incomplete without a clear understanding of the strategic political and economic motivations of the latter. This paper also draws conclusions about how EAI reflects South Korea’s national and regional aspirations, as well as the security implications for the relationship and interaction between the two countries’ alternate visions for a Eurasian continent. While Korean and Chinese visions superficially share a broad and similar goal of connecting two separate regions, ultimately their visions diverge fundamentally on conflicting understandings about national and regional security, and the political and economic roles that each country plays in achieving their ambitions.

Conclusion

In today’s uncertain global environment with new threats and crises emerging with startling frequency, the Korean Peninsula unfortunately remains the focal point of a steady and compelling security problem, as it has for almost 70 years. Aside from the profoundly tragic human costs of the continued division of the Korean people, the political consequences of ongoing tensions and the potential for an outbreak of the Korean War frozen for 63 years has global ramifications, not the least because it could involve military confrontation among the world’s three largest nuclear weapons powers—the United States, China, Russia— and of course now North Korea as an “illegitimate” nuclear power. Yet, a permanent resolution of the bitter division of the Korean Peninsula has perhaps equally profound consequences for the future of the entire Asia-Pacific-Eurasia region, and may even hold the key to possible integration of the Eastern and Western worlds.

China has embarked on an astonishingly ambitious path to link several continents under a new informal architecture shaped by its desire to expand extra-territorial stability. Yet, the purposefully limited view westward (and north and south) with the explicit exclusion of its easternmost neighbor, the Korean Peninsula which is economically and strategically crucial for true regional integration, is strikingly stark. It is perhaps further confirmation that for China, maintenance of the status quo— division of the Korean Peninsula—even with North Korea’s ongoing pursuit of nuclear weapons programs, serves Chinese strategic goals: ensuring extra-territorial stability especially in its bordering countries.

Such entrenched Chinese interests are increasingly at odds with South Korea’s own vision for the region, supported by its growing confidence as a solid middle power. Exacerbating Korean skepticism about Chinese regional ambitions has been Beijing’s increasing boldness in asserting its power in the region, as evidenced by China’s unilateral declaration of an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) in November 2013, which shocked many South Koreans because of its inclusion of Ieodo (or “Parangdo” by Korea), a rock that China claims as part of its territorial rights (Suyan Rock).55 Thus, the ROK’s “Eurasian Initiative,” despite purporting to share similar goals with OBOR of reviving the ancient Silk Roads to promote economic benefits for all involved, is far more likely to be divergent paths than a shared road.

Yet, more than the potential loss of long-term regional benefits, the divergence between the two visions for extra-regional integration signal a deeper and troubling disparity in fundamental views about regional security. China’s refusal to acknowledge the obstructionist role that North Korea plays not only against regional integration but stability on the Peninsula is being acknowledged and challenged by the South Korean leadership, and increasingly by the public. The negative Chinese reaction to Seoul’s decision to deploy the U.S.-led THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defense) system, while unsurprising, was startling in its vehemence, and has only served to increase South Korean suspicions about Chinese ambitions.

Indeed, Chinese willingness to insert itself into the domestic debate on South Korea’s sovereign right to defend itself is indicative of the extent to which China’s preoccupation with stability in its extra-territorial regions is crucial to its own perception and needs regarding its national security. Meanwhile, North Korea’s ability to assert its own independent actions despite regional and global pressures highlight the opportunities for exploitation created by the inability of regional powers to cooperate when national security interests diverge. Thus, the respective grand projects promulgated by China and South Korea to revive the ancient Silk Roads in order to promote regional integration may paradoxically unleash greater divisions in the Asia-Pacific, and fail to deliver the regional stability both nations are striving to achieve.

Please click to read the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

In its 13th Five-Year Plan, Guangxi has made accelerating the growth of processing trade one main thrust of its outward economic development. It aims to increase the value-added of processing trade by encouraging the diversification of assembly processing into R&D, design as well as upstream and downstream sectors. It also wants to establish a “Nanning-Qinzhou-Beihai Electronic Information Processing Trade Industry Belt” by using processing trade parks and bonded zones as carriers. As Guangxi’s processing trade trends towards mid- to high-end, some of the labour-intensive processes have started to move out and industry chains are being formed with neighbouring ASEAN countries.

Processing Trade Develops in Leaps and Bounds

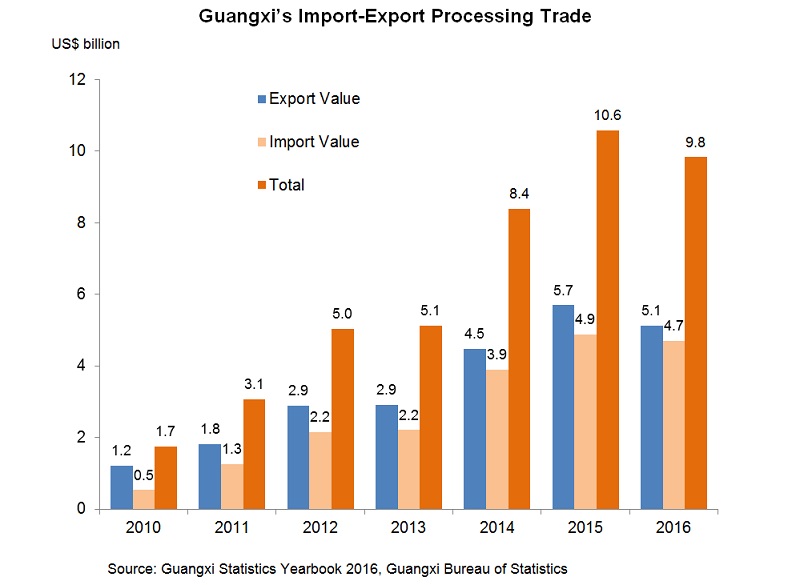

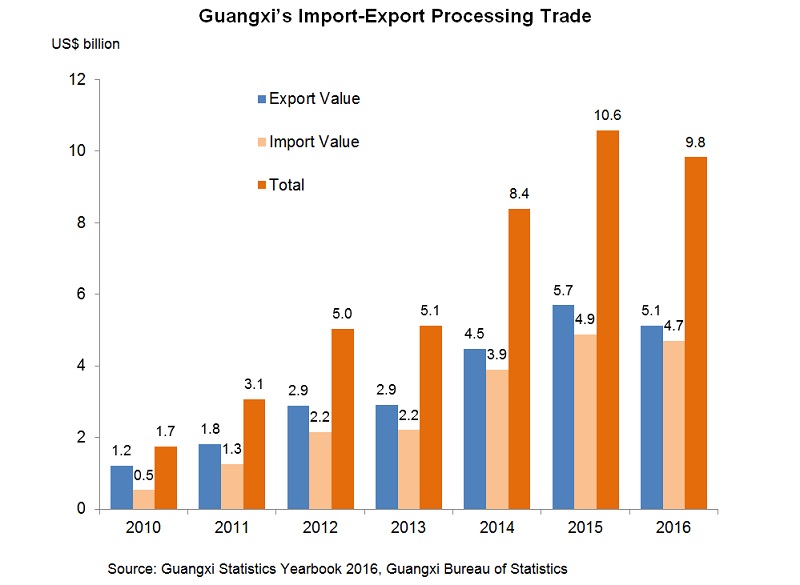

The past few years have seen marked growth in Guangxi’s processing trade. Higher logistics costs notwithstanding, a considerable number of industries in China’s eastern region have moved into the autonomous region. Although in 2016 overall external demand was sluggish and Guangxi’s exports also dropped, from 2010 to 2016 Guangxi’s total import and export value from processing trade still registered a hefty average annual growth rate of 33.3%. In particular, processing trade exports grew at an average annual rate of 27.2%. In 2010, processing trade constituted 9.9% of Guangxi’s overall external trade, but the figure climbed to 20.6% in 2016. Currently, the raw materials, parts and components used in processing trade come from different areas, but exports after assembly mostly transit through Hong Kong.

Further Driving Processing Trade

In a bid to further drive processing trade development, Guangxi proposed a second round of “doubling plan” in 2016. The Implementation Opinions on Promoting the Innovative Development of Processing Trade (the Implementation Opinions) it released in June 2016 proposed that by 2020, the import and export volume of processing trade will double that in 2016 to more than US$20 billion. Meanwhile, there should be further improvements in the structure of export goods from processing trade, with mechanical and electrical products and high-tech products comprising more than 75% and 50%, respectively, of all processing trade exports.

The Implementation Opinions proposed a number of incentive measures to support the development of the processing trade industry, including:

- Processing trade enterprises whose projects fall under the scope of the Catalogue of Encouraged Industries in the Western Region with total investment exceeding RMB50 million will be eligible, up to 31 December 2020, for a reduced enterprise income tax rate of 15% while contribution to local coffers will be exempted.

- In key industrial parks, basic endowment insurance premium will be reduced from 20% to 14% while collection of contributions to the water conservancy fund will be temporarily suspended for processing trade enterprises in these parks.

- For projects in priority development industries with intensive land usage as determined by Guangxi, the minimum land assignment price may be set at no less than 70% of the relevant standards.

- Concerted efforts will be made to give more financial support to processing trade transfer projects. In 2016, a total of more than RMB600 million in specific funds, inclusive of RMB300 million from the Guangxi government and funds from the central government designated for foreign trade and economic development, were allocated for further improving the environment for the development of processing trade industries.

As for labour costs, take the city of Beihai as an example. According to Beihai Industrial Zone (BIZ), the average monthly wage of an ordinary worker is about RMB2,500. It is worth noting that some Guangxi cities along the Sino-Vietnamese border are stepping up labour services co-operation with neighbouring Vietnamese regions. With the signing of a cross-border labour services co-operation agreement in early 2017 between the Guangxi border cities of Chongzuo, Fangchenggang and Baise with the Vietnam border provinces of Quảng Ninh, Lang Son, Cao Bang and Ha Giang, a mechanism for labour services co-operation has been formally set up.

With the sustained development of Guangxi’s economy, labour demand at the autonomous region’s border regions will also grow rapidly. As neighbouring Vietnam has surplus labour, cross-border co-operation in labour services is conducive to Vietnam workers going to work in Guangxi. It has been estimated that the labour cost of each cross-border worker is lower than that of a Guangxi worker by more than RMB10,000 a year.

Processing Trade Trending Towards High Value-added

In recent years, Guangxi’s industrial structure has been turning gradually towards high technologies and electronics, so its processing trade is also advancing in that direction. To promote further processing trade development, the Implementation Opinions suggest that active guidance should be given on bringing in whole chains of supporting industries so that Guangxi’s processing trade can be developed in clusters and its value-added can be increased continually. The autonomous region is now building an electro-plating park in Tieshan port area to provide support for related upstream industries.

Beihai hosts some 600 large and small enterprises in the field of electronics, one of the fastest-growing industries locally. Electronic information is the pillar industry in BIZ, followed by food, pharmaceuticals and equipment manufacturing. According to a BIZ representative, the industry chains there are now extending upstream in the direction of R&D, and BIZ has set up a foundation for supporting this sector. So far, BIZ is host to five state-level high-tech enterprises and eight provincial-level R&D centres and technology centres; it has also set up the first quality inspection centre in Guangxi for electronic information products.

About 20,000 workers are employed in BIZ and the number is expected to hit 30,000 in 2017. Most are local and there is little problem with recruitment. However, one BIZ representative said that labour demands of enterprises now entering the zone are less urgent than before, and they are more concerned with local support in terms of value improvement. BIZ is well aware that, in the long-run, it cannot depend on incentive policies alone. Instead, there is a need to develop support services and upgrade the standards of industrial services including, for example, raising the standards of inspection and testing services, offering certification of standards, and training of personnel, all of which are vital in lending support to R&D. To further enhance the business environment, BIZ will also set up a port joint inspection centre to facilitate customs clearance.

Industry Chain Relationship with ASEAN

For its processing trade, Guangxi uses raw materials, parts and components from different sources, while exports after assembly mostly transit through Hong Kong. Guangxi’s processing trade, however, has ceased to be simple processing with supplied materials: enterprises using Guangxi as a production base make use of labour forces in peripheral areas to carry out and incorporate international co-operation in production capacity. Guangxi figures indicate that some enterprises in the Beibu Gulf area have begun to gradually transfer some low value-added, and very labour-demanding, processes to ASEAN countries.

Although the productivity of Guangxi’s workers is higher than that of their counterparts in some ASEAN countries such as Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, labour costs in Guangxi are also higher. Consequently, some manufacturers in the Beibu Gulf area have started carrying out industrial division of labour with neighbouring ASEAN countries. This entails outsourcing some simple assembling processes to Vietnam or Cambodia, then shipping back the semi-finished products for further assembly in Guangxi. In this way, a processing trade industry chain involving Guangxi and ASEAN has begun to take shape.

As an example, a Taiwan electronics enterprise has invested in an industrial park in Cambodia through a company it has set up in Beihai. Semi-finished products produced by lower-cost labour in Cambodia are shipped back to Beihai for deep processing or final assembly. Since low-end processes have been transferred to Cambodia while mid- to high-end processes are retained in Beihai, the number of workers the enterprise employs in Beihai has been reducing gradually from 4,000 in 2015 to about 2,000 in 2016. Although there is a reduction in the number of workers, overall output value has not decreased.

From Guangxi’s perspective, this is an inevitable development trend. Even though enterprises are moving out some production processes, Beihai no longer wants to take in low-end, low value-added electronics industries. Industrial parks also want to create a sound operating environment so that enterprises will continue to use Beihai as a management centre while building industry chains with ASEAN countries.

Given the fact that the electronics industry requires specialised services support, BIZ, for example, has established an electronic information product inspection and testing centre so that enterprises do not have to send their products outside Guangxi for inspection and testing. The next step is to provide various types of quality certification locally. A port joint inspection and testing centre will also be set up to allow formalities such as customs declaration and commodity inspection to be carried out within the park premises. A skills training school has also been set up inside the park through the joint efforts of businesses and academic institutions to train related technical staff.

|

China-Malaysia Qinzhou Industrial Park China-Malaysia Qinzhou Industrial Park (CMQIP) has been jointly built by government consortia from Malaysia and China. It is one of the two parks under the “two countries, twin parks” co-operation between China and Malaysia (the other is Malaysia-China Kuantan Industrial Park in Kuantan Port, Malaysia). About 15km from the city of Qinzhou, CMQIP has a planned area of 55 sq km. The first phase will cover 15 sq km, of which 7.8 sq km is designated as a start-up area. It is expected that the whole 15 sq km will be developed in 2017, well ahead of the target date of 2020. By early 2017, 66 enterprises had signed agreements to set up operations in the park or were about to do so. CMQIP is intended as an international park and enterprises from around the world are welcome. Standard factory buildings with worker dormitories are available in its processing trade zone. To the east of CMQIP is Sanniang Bay, a 4A grade tourist district; to the west is Maowei Sea, a national ocean park. CMQIP will therefore make use of tourism resources in its neighbourhood to create an international tourist attraction complete with facilities for leisure, vacationing, business, conventions and exhibitions, culture and sports. CMQIP had its foundation laid in 2012 and, after years of efforts in infrastructure building, it is now ready for enterprises to move in and operate. Six industrial clusters are gradually being built up: medicine and healthcare, information technology, marine industry, equipment manufacturing, materials and new materials, and modern services (including cultural creation and tourism). In addition, talks are also under way to introduce traditional Malaysian priority industries such as bird’s nest processing, halal food and rubber, as well as the deep processing of palm oil imported from Malaysia. In choosing sites for the twin parks, Malaysia and China have decided on a port city with a view to co-operating in the development of both industry chains and logistics chains. Industries now located in Malaysia-China Kuantan Industrial Park include steel and aluminium processing and ceramics, and they have set their sights on the regional market. CMQIP intends to tighten Chinese-Malaysian industrial co-operation. At this stage it is bringing in different types of industries in order to make the park a success. It also has plans to gradually introduce Malaysia’s priority industries such as bird’s nest processing and halal food processing. At the end of 2016, with China and Malaysia signing the Protocol on Inspection, Quarantine and Veterinary Hygiene Requirements for the Exportation of Raw, Uncleaned Edible Bird’s Nest from Malaysia to China, Qinzhou and CMQIP in Guangxi may become the designated port of importation and processing base, respectively, for Malaysian raw bird’s nest. |

Bonded Zones Offer More Value-Added Development

Guangxi’s 13th Five-Year Plan mentions that better use should be made of various bonded port zones and export processing zones to step up the development of processing trade. In fact, its bonded port zones are now promoting the development of more value-added activities in different industries. For example, Nanning Bonded Port Zone not only runs a bonded warehouse, but it is also venturing into the exhibition and maintenance of imported cars, repairing of returned exported equipment, aviation logistics, aeroplane related maintenance and training, as well as the deep processing of imported food and health food.

Qinzhou Bonded Port Zone (QBPZ) is pursuing the processing of imported cotton in its bonded zone. The yarns from spinning can either be imported into mainland China or exported. On the mainland, imported fruits and meat must be imported through designated ports that are equipped with inspection and testing facilities. QBPZ is also qualified in this respect, so it is planning to develop the processing of cold-chain imports, targeting mostly imported fruits and meat where the main processes involved are cutting and repackaging. Another project is wood processing, in which imported bonded wood is processed into boards or wooden components for buildings. QBPZ is also developing cross-border e-commerce, aiming to offer a platform for ASEAN SMEs to enter the China market by helping them handle import formalities. Its position is to focus on specialty products from Southeast Asia, and its target markets are Guangxi and the southwestern region.

It is worthwhile for Hong Kong’s manufacturing industry to pay attention to the progress of Guangxi’s efforts in promoting co-operation in production capacity with ASEAN. Hong Kong can capitalise on the development room available to integrate regional supply chains more effectively. Guangxi’s electronics industry has been growing rapidly in recent years. To support the development of the industry, a modern electro-plating industry park is being planned in Tieshan Port, Beihai. Nevertheless, Guangxi’s manufacturing sector still lacks supportive professional services such as R&D, brand promotion, inspection and testing, etc. These vital aspects in manufacturing can offer opportunities for co-operation between Hong Kong’s related sectors and Guangxi’s manufacturing industry.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Alek Chance, Institute for China-America Studies

Executive Summary

This report is a survey of common views on China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) among American strategic studies and international political economy experts. These observations are placed against the backdrop of BRI’s potential to make significant contributions to global economic development, and they comprise a point of departure for a set of preliminary recommendations for using the initiative to improve the US-China relationship. This report maintains an agnostic position regarding the current strategic intentions behind BRI or its future course. However, the scale, scope, and centrality of BRI to China’s foreign and economic policy all invite an examination of its potential to enhance the US-China relationship, and to identify factors that either might facilitate or stand in the way of realizing this potential.

Key Findings:

- BRI is largely regarded among American experts to be a seriously pursued initiative with the potential to significantly impact the economic and political future of Eurasia. However, the overall response to BRI has been ambivalent, with Americans expressing frequent concerns about standards, the adequacy of Chinese development practices, and the erosion of Western development norms.

- Geopolitical concerns significantly frame Americans’ views of BRI. The initiative is sometimes viewed a deliberate attempt to economically marginalize the United States, to create a Eurasian sphere of influence, or as a pretext for expanding China’s overseas military presence. At the very least, perceptions that China is embarking on a new, “assertive” phase of statecraft elevate the scrutiny BRI faces.

Key Recommendations:

- The United States and China should both envision BRI as a vital instrument for strengthening habits of cooperation. BRI must be shaped in a way that places it on the cooperative rather than competitive side of the US-China relationship.

- Chinese experts and policymakers should work to address American (and indeed, global) concerns about the standards and inclusiveness of BRI, and about China’s commitment to existing norms and economic regimes.

- Americans should remain open-minded and flexible about BRI. The US should engage with it where it serves US interests rather than viewing the entire initiative through the often simplistic lens of geopolitical competition.

- The US and China should establish dialogue and collaboration mechanisms focused on exploiting areas of overlapping interests in the BRI domain and to coordinate their different, yet complementary, strengths in development.

Please click to read the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Hong Kong has an online environment that other countries can “only dream about”, says Michael Gazeley of locally-based but global cyber security firm, Network Box. He says China’s Belt and Road Initiative consists of online (as well as land and sea) trading links and Hong Kong can rely on its fast, stable Internet and world class infrastructure to safely connect up the cyber Belt and Road. Catch Part 2 on Hong Kong’s expertise in cyber security.

Speaker:

Michael Gazeley, Managing Director, Network Box Corporation Limited

Related Links:

Hong Kong Trade Development Council

http://www.hktdc.com/

HKTDC Belt and Road Portal

http://beltandroad.hktdc.com/en/

By Vivienne Bath, The University of Sydney Law School

China’s changes to its inbound and outbound investment system, in addition to its programme of BIT (bilateral investment treaties) and FTA (free trade agreements) negotiations, are relevant to investments in and from OBOR countries, but are part of an on-going reform process that is not driven by the OBOR vision. The SPC and Chinese commentators recognise that investment in the OBOR will raise a number of legal issues for investors, but appear to be focused on improving China’s own legal system and its network of current and potential international treaties, primarily BITs and FTAs, as the primary method of dealing with disputes. However, it is clear that protection under China’s current network of BITs along the OBOR is by no means assured, due to the limited content of most of the treaties and potential issues in individual countries with a poor record in terms of rule of law.

Does China have – or should it have – a specific strategy in relation to investment protection agreements focused on the states along the OBOR, and if so what form should it take? In general, the individual countries with which China has negotiated and is currently negotiating FTAs are not states along the OBOR, although regional agreements and negotiations with ASEAN, the European Union and potentially a new Central Eurasian agreement may provide opportunities for strengthened investment agreement protections in some of those states. China’s current emphasis in negotiating agreements with countries along the OBOR seems to be on joint declarations for expanding cooperation and entering into comprehensive strategic partnerships rather than new BITs or investment agreements, although these may be the precursors to more formal state-to-state arrangements.

It is questionable whether China’s long-term interests and aims under the OBOR vision would be well-served by an aggressive programme of negotiating more rigorous investment agreements and attempting to enforce the rights of investors through investor-state arbitration. Indeed, despite an increase in ISDS cases, Chinese investors have been very cautious in relation to attempts to enforce their rights through these means.

This raises the question of the role of the Chinese government in both deal making and protecting the rights and interests of Chinese investors. The Vision Document and other policy documents relating to the OBOR certainly suggest that the Chinese government sees itself as playing an active role in planning and putting its weight behind the expansion outwards as contemplated in the OBOR vision. The provision of funding by Chinese owned and backed institutions,94 when combined with the on-going requirement that Chinese government approval be obtained for major acquisitions and investments and for investments in sensitive countries and investments, also indicate that the Chinese government will play an on-going regulatory role in OBOR investment. These investors may well assume that the Chinese government will continue to be closely involved in their operations and in the behind-the-scenes settlement of disputes relating to investments, particularly in states with a weak legal regime and a poor record in terms of investment disputes.

In summary, reforms to China’s current regulatory and funding regime both encourage outbound investment and support continued government involvement in both the establishment and operation of overseas investments. Due to China’s assertive policy of negotiating BITs and, more recently, FTAs, there is a network of treaties with states along the OBOR designed to promote and protect investment. However, investment protection for Chinese investors still presents challenges, due both to the restricted protections offered by the earlier treaties and the risk associated with a significant number of the host countries along the OBOR. It can therefore be anticipated that the Chinese government will play a continuing role both in encouraging and funding investment along the OBOR and in assisting with disputes.

(Lutz-Christian Wolff and Xi Chao (eds), Legal Dimensions of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, Wolters Kluwer Hong Kong Ltd, 2016, pp165-218.)

Please click to read the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Belt and Road investment priorities and need to boost northern states fuels expansion of Special Economic Zones.

The development of Malaysia's growing number of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) is being shaped by several investment requirements related to the Belt and Road Initiative, as well as by a change in priorities on the part of the country's government.

As the Malaysian government looks to diversify the country's economy, it faces three key challenges, all of which have implications for the SEZ sector. Firstly, it is keen to rebalance economic growth across the country while looking to nurture innovation in the digital-technology sector. On top of that, it is determined to capitalise on the new opportunities emerging from the ASEAN integration programme.

With inward investment focussed almost exclusively on Kuala Lumpur and the southern states of Selangor and Johor, promoting interest in the country's northern regions is seen as a vital part of any move to rebalance the economic map. The key project here is the development of the East Coast Economic Region (ECER), an initiative that was initially green-lit in 2008.

As envisaged, the ECER spans the northern states of Kelantan and Terengganu, as well as Pahang in the east and Mersing in southeastern Johor. It extends across 51% of Peninsular Malaysia, and focuses primarily on the country's traditional strengths in manufacturing, agribusiness, oil, gas, petrochemicals and tourism.

As of May 2016, some 38.5% (US$3.1 billion) of all inbound investment in the ECER had been sourced from Chinese investors. The majority of this funding has been channelled into the Malaysia-China Kuantan Industrial Park. Set in the eastern coastal state of Pahang, this was the first industrial park in the country to be jointly developed by Malaysia and China. Among the more recent investments has been the funding of a $133 million aluminium component manufacturing facility by the Guangxi Investment Group.

In order to create much-needed jobs, however, the northern states require considerably more investment. In line with this, back in 2016, the Terengganu state government lobbied to launch a new SEZ extending across Besut, Setiu, Kuala Nerus, Kuala Terengganu and Marang. The proposed 729,400-hectare development is said to have been modelled on the Shenzhen SEZ in southern China. At present, it is planned that the initial phase will utilise some 221,000 hectares, with the second phase requiring an additional 508,400 hectares.

With improving the country's digital infrastructure one of the key elements in the government's plan to encourage multinationals and SMEs to create new jobs, Malaysia launched the world's first Digital Free Trade Zone (DFTZ) in March this year. The ceremony to mark the formal adoption of the scheme was attended by Najib Razak, the Malaysian Prime Minister, and Jack Ma, the Executive Chairman of Alibaba Group and an adviser on the development of Malaysia's digital economy.

Once completed, the DFTZ will boast an e-fulfilment hub at the Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KLIA) Aeropolis, a 405-hectare development zone focussed on air cargo and logistics as well as the development of an aerospace/aviation cluster. The initial phase will roll out later this year, with Alibaba, Cainiao, Lazada and POS Malaysia already signed up as tenants. The facility will also be the launch site in 2019 for Alibaba's Electronic World Trade Platform – part of the company's bid to streamline global trade arrangements for SMEs.

The second phase of the DFTZ will see the establishment of the Kuala Lumpur Internet City (KLIC). Developed by Catcha Group, the Malaysian/Singaporean internet giant, it is hoped that KLIC will emerge as the key digital hub for global or local internet-related companies looking to target Southeast Asia.

The project will be housed within Bandar Malaysia, a commercial and residential zone located on the site of a former air-force base. The site is being developed by a consortium led by the China Railway Engineering Corp.

In other developments, Bandar Utama, on the outskirts of the capital, will be the terminal for the Kuala Lumpur-Singapore high-speed rail link, scheduled to begin operation in 2026. With a journey time of just 90 minutes, the link is expected to boost business and tourism traffic.

At present, stops are planned at Putrajaya, Seramban, Alor Gajah, Muar, Batu Pahat and Iskandar Puteri in Johor Bahru. All of these locations are intended to be promoted as investment hubs in the coming years, with Iskandar Puteri having something of a head start over the other designated sites.

Forming part of Iskandar Malaysia – the main southern development corridor in the state of Johor – Iskandar Puteri is a 2,217-square-metre SEZ. Established in 2006, it was envisaged as a world-class business, residential and entertainment hub, with its management keen to capitalise on its proximity to Singapore.

Among the businesses already operating within its precincts are Legoland Malaysia, Gleneagles Medini Hospital and Pinewood Iskandar Malaysia Studios. It is also the site of the Medini 'smart city', one of Malaysia's largest urban developments.

Within Medini, investors in six designated sectors – health and wellness, education, financial services, leisure and tourism, the creative industries, and logistics – can take advantage of a number of tax breaks and several other incentive packages. The site is expected to get a further boost in 2019 following the completion of a high-speed rail link to Singapore's Mass Rapid Transit rail system.

In addition to developing domestic SEZs, the country's Ministry of International Trade and Industry has announced that a number of Malaysian companies will be playing key roles in developing several SEZs in neighbouring Laos. These include Savan Park, a commercial and industrial hub jointly funded by the Laos government, and Savan Pacifica Development, a Malaysian consortium.

Among the other projects is the Dongphosy SEZ, a 70-hectare duty-free retail and residential zone intended to promote tourism, which is being jointly developed by Malaysia's UPL Lao and the Laos government. Malaysian companies are also involved in the development of an SEZ in Thakek, southern Laos.

Geoff de Freitas, Special Correspondent, Kuala Lumpur

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Michael M. Du, School of Law, University of Surrey, UK

Abstract

With the launch of “One Belt, One Road” Initiative, China is injecting vitality into the ancient Silk Road. While China is seen to embrace it as the centrepiece of its economic strategy, the new Silk Road Initiative, if well implemented, is expected to bring forth the opportunity of economic prosperity for both China and the countries in the region. Against the backdrop of the complicated and volatile geopolitics in the mega-regions and the voracious needs for gigantic inputs of resources, etc., however, the operationality of the Initiative is in contrast with the grandiose discourse by the Chinese authorities. In particular, where China’s ultimate target is set to shape a new structure for global economic governance, its ability to lead vis-a-vis its targeted partners’ readiness to cooperate, among others, remain to be tested.

Implications for China

The SREB (Silk Road Economic Belt) / MSR (Maritime Silk Road) strategy is expected to feature prominently in China’s 13th Five-Year Plan, which will run from 2016 to 2020 and guide national economic and social development strategy throughout that period. Its immediate implications are as follows:

The strategy will secure the transport of oil and gas and other essential goods, and particularly access to the Central Asian energy resources needed to sustain China’s economy. The property and investment boom at home has now ended, leaving China with significant overcapacity in industry and construction, deflation and rising debt management problems. The implementation of the strategy can ease the entry of Chinese goods into regional markets, help make use of China’s enormous industrial overcapacity, thus offsetting the effects of a falling investment rate and rising overcapacity at home.

China has been tired of accumulating endless volumes of US Treasury and other government bonds, and now prefers more direct investment overseas to make a better use of its more than $4 trillion foreign exchange. Equally important, the SREB/MSR can improve internal economic integration between the country’s advanced coastal and the more backward western provinces. These are the strategy’s intermediary implications.

With respect to the long-term implications, by linking the economies of Central Asia with western China, China is expected to bring further development and stability to restive and relatively underdeveloped Xinjiang and Tibet regions and cuts off any potential support that Uygur dissident groups may seek from fellow Muslims in Central Asia. With the unfolding of the SREB/MSR strategy, China will be in a position to promote the global use of RMB which is likely to lead to the internationalization of RMB.

Implications for Partners

Needless to say, the SREB/MSR strategy will have its implications for the participating countries along the Belt and Road. Properly implemented, the SREB/MSR strategy will likely have an important effect on the region’s economic architecture—infrastructure development, patterns of regional trade and investment. However, this rests on their own perception of interests therein and the extent of cooperation they offered. It is not surprising if they argue SREB/MSR is too China-centric and that other participating states will reap only marginal benefits.

Implication for Global Governance

China has long expressed opposition to the dominance of the US and the dollar in the global financial institutions, most notably the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. The SREB/MSR strategy is the upgraded version of China’s grand strategy of opening-up, as well as China’s strategy for globalization. Globalization has been so far mainly driven by the West. With the unfolding of the SREB/MSR strategy, non-Western countries are going to inject vitality.

The Chinese version of globalization needs to nurture shared interests, shared system and effective dispute settlement mechanism.

Another concern is that some Western officials also fear that a flood of Chinese development money will undermine governance standards at existing lending institutions like the World Bank, especially if China channels funds to its own companies, to politically motivated projects or to environmentally damaging ones.

An even deep concern beneath, which results from the distaste for the Chinese governance structure and state-led economic structure, is whether China will extend and deepen its global footprint without fundamental changes in political and economic philosophy.

Please click to read the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Guangxi has a strategic role to play in both the Belt and the Road. The autonomous region’s “four-dimensional support” development strategy includes further opening up to the east with emphasis on strengthening co-operation with Guangdong and Hong Kong, such as forging closer collaboration with Hong Kong’s professional services under the Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement’s (CEPA) early and pilot measures, and encouraging Hong Kong and foreign enterprises to participate in Guangxi’s construction projects in relation to the Belt and Road Initiative, including the China-ASEAN information port as well as transport and logistics facilities serving ASEAN countries. Meanwhile, Guangxi also hopes to co-operate with Hong Kong companies in advancing the two-way development of its enterprises in “going out” and “bringing in”.

Guangxi Spreads Across Both Belt and Road

The Belt and Road Initiative aims to achieve economic policy co-ordination of countries along its routes, and promote the orderly free flow of economic factors, the highly effective distribution of resources, and in-depth market integration. In addition to the large number of countries along the routes that will participate in building the Belt and Road, different provinces, regions and cities in China are also proactively involved in contributing to the initiative.

According to the Vision and Actions on Jointly Building the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road issued by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) in March 2015, in advancing the Belt and Road Initiative, China is to give full play to the comparative advantages of various regions in the country. Vision and Actions pointed out that efforts would be made to “give full play to the unique advantages of Guangxi in regard to its geographical connection with ASEAN countries by land and by sea, expedite the pace of opening up and developing the Beibu Bay Economic Zone and Pearl River-Xijiang Economic Belt, build international passages serving the ASEAN region, create a new strategic stronghold for the opening-up and development of the southwest and central south regions, and develop an important gateway for the organic integration of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road and the Silk Road Economic Belt”.

Vision and Actions set out three key directions for co-operation in building the Silk Road Economic Belt over land, namely China with Southeast Asia, South Asia, and the Indian Ocean. Meanwhile, the key direction for co-operation in developing the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road by sea is from China’s coastal ports to the Indian Ocean via the South Sea on to Europe, as well as from China’s coastal ports to the South Pacific Ocean via the South Sea.

In terms of geography, Guangxi shares land borders with Vietnam and is situated in a key geographical position in terms of China’s land connections with Southeast Asia. At the same time, the many ports in Guangxi’s Beibu Bay Economic Zone offer much room for the development of sea connections. As such, Guangxi plays a strategic role in both the Belt and the Road.[1]

Strengthening Transport Links Between Inland China and Southeast Asia

Under the development directions of the Belt and Road, Guangxi is expediting its pace of implementing the “four-dimensional support and four-alongs interaction” strategy aimed at strengthening opening up and co-operation internally and externally. The focus of “four-dimensional support” is giving emphasis to the key direction of opening up to the outside world.

First of all, efforts are to be made to further open up to and enhance co-operation with the south, positioning Guangxi as one of the mainland’s contact points in connecting to the Indochina Peninsula. Such efforts also aim to deepen co-operation with ASEAN countries along the Belt and Road, such as building an international co-operation platform and seeking international co-operation in production capacity. With regard to land passages, actions are to be taken to expedite construction of the East Line of the Pan-Asia Railway and highways running from Nanning through Hanoi and Phnom Penh to Bangkok.

Secondly, steps are to be taken to further open up to the east, with emphasis on enhancing collaboration with Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macau, including strengthening co-operation with Hong Kong’s professional services under the CEPA early and pilot measures. Thirdly, efforts are to be made to forge co-operation with important hinterland regions in the southwest and central south (including Yunnan, Guizhou, Sichuan, Chongqing, Hunan and Hubei), and to build passages and establish platforms for these two regions. And fourthly, steps are to be taken to further open up to and strengthen co-operation with developed countries, align with the advanced level of productivity of such developed countries and regions as the EU, Japan and Korea, as well as to further raise the level of internationalisation of Guangxi.

“Four-alongs interaction” refers to the opening up of areas along the sea coast, along the river, along the border, and along the Belt and Road.

Along the sea coast: Guangxi seeks to open up further and expand co-operation along its sea coast, increase the capacity of its ports and their ties with the hinterland, and develop Nanning into an integrated transport hub.

Along the river: Development and co-operation along the river means using the Xijiang golden waterway as the base to expand co-operation between Guangdong and Guangxi, while deepening unified Pan-PRD co-operation.

Along the border: Border trade in Guangxi, with a border of 1,020km, plays an important role in the autonomous region. Efforts will be made to promote collaboration between cross-border economic co-operation zones and advance new development in border areas.

Along the Belt and Road: This refers to the building of expressways and high-speed railways from Guangxi to neighbouring countries along the Belt and Road routes. Capitalising on these transport links, passages for opening up, industrial development and complementariness are to be built. Guangxi has already constructed 13 expressway passages, 11 railway passages and a 2,000-tonne class waterway passage leading to neighbouring provinces and countries.

According to the Guangxi Transport Department, four expressways linking Guangxi with Vietnam have been planned. Indeed, two have already been completed: Nanning to Friendship Gate, and Nanning to Fangchenggang/Dongxing. Meanwhile, construction of the expressways from Baise to Longbang and from Nanning via Chongzuo to Shuikou is under way and both are scheduled for completion by 2019. It is hoped that Vietnam can also accelerate its construction of highways linking to Guangxi.

Drawing on the optimised transport links, Guangxi is actively strengthening its role as the gateway to ASEAN. Since 2016, cargo flows between Guangxi and Thailand have been on the rise. According to the local commerce department, total trade between Guangxi and Thailand grew 32.9% from January to November 2016. Most of the goods were electronic products exported from Thailand to Guangxi by land through Pingxiang for distribution to Yangtze River Delta cities such as Suzhou. In the past, it took about 14 days for goods to be transported from Bangkok to Suzhou by sea, but today it only takes about six days via Guangxi by land. Improvement in trading infrastructure is set to enhance the position of Guangxi as the gateway to ASEAN.

Directions For Co-operation With ASEAN

As an international passage serving ASEAN countries and an important gateway for organic integration, Guangxi plans to forge co-operation with ASEAN in a number of major directions. The potential opportunities provided by the long-term development directions and individual projects for related industries are worth noting.

According to the Guangxi Development and Reform Commission, Nanning, as a regional integrated transport hub, is designated by Guangxi as the core for land connectivity, linking with the Indochina Peninsula to the south and connecting with the Eurasian Land Bridge to the north. With regard to sea connectivity, emphasis is being placed on developing Beibu Bay into a regional shipping centre, as well as building the China-ASEAN port cities co-op network. It is understood that since the China-ASEAN port cities co-op network was built in 2013, 10 new shipping routes have been opened. At the same time, great efforts are being made to advance collaboration in such areas as ports, industry, monitoring, rescue and the judiciary. This has in turn facilitated the flow of people and cargo between China and ASEAN.

In the days to come, the focus of co-operation will be on establishing a shipping and logistics service system, including setting up a regional port logistics technology standardisation system, promoting co-operation in port investment and operation, and deepening collaboration between port industries. At present, Guangxi is quickening its pace in building a network of shipping routes covering 47 port cities in ASEAN countries. Some 35 regular container liners currently sail from Guangxi’s Beibu Bay, establishing marine transport links with ASEAN countries such as Brunei, Indonesia and Malaysia. Where forging closer co-operation in commerce and logistics is concerned, Guangxi attaches importance to promoting the China-ASEAN bulk commodities trading centre, improving the functions of the bonded logistics platform, and developing cross-border e-commerce.

Under the Belt and Road Initiative, strengthening industrial co-operation with regions along the routes is one of the important development directions. In this connection, Guangxi places emphasis on building cross-border industry chains, with priority given to promoting the China-Malaysia Qinzhou Industrial Park in Qinzhou, Guangxi, and the Malaysia-China Kuantan Industrial Park in Kuantan, Malaysia; the China-Indonesia Economic and Trade Co-operation Zone; and the Brunei-Guangxi Economic Corridor; as well as building the China-ASEAN agricultural co-operation base.

Furthermore, actions have been taken to accelerate the pace of building the Guangxi border comprehensive financial reform pilot zone and promoting innovative cross-border renminbi business. There are plans to build the China-ASEAN environmental co-operation demonstration platform and the China-ASEAN environmental technology exchange co-operation base.

Efforts are also being made to further advance construction of the China-Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor by leveraging such leading co-operation platforms as the China-ASEAN Expo and Pan-Beibu Bay Economic Co-operation Forum. For instance, when the Pan-Beibu Bay Economic Co-operation Forum was held in 2016, the China-Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor Development Forum and the China-ASEAN Port Cities Co-op Network Work Conference were convened coincidentally. These platforms for co-operation have now become major avenues for political and commercial exchanges with ASEAN.

It is worth noting that in 2015, China proposed at the 12th China-ASEAN Expo that a China-ASEAN information port be built. Its aim is to deepen network connectivity and information interflow with a view to creating a China-ASEAN information hub with Guangxi as the fulcrum, as well as promoting online economic and trade services and technological co-operation. Construction work will be carried out in two stages.

First, actions will be taken to build a number of basic projects and plan a number of industrial bases serving ASEAN to form a preliminary framework for the China-ASEAN information port. Then from 2018 to 2020, the China-ASEAN national information communication network system will be built to create a big service platform for infrastructural facilities, technological co-operation, economic and trade services, information sharing, and cultural exchanges. The Guangxi Development and Reform Commission pointed out that the China-ASEAN information port involves more than 100 projects, embracing Asia Pacific international direct dial submarine optical cables, China-Vietnam and China-Myanmar cross-border optical cable system capacity expansion, a cloud computation centre, and a big-data centre. Upon completion, it will form a basic network of information integrating with ASEAN.

Enhancing ASEAN Trade Facilitation

In its efforts to strengthen ties with ASEAN, Guangxi not only gives weight to developing infrastructure such as transport and information networks, but also enhances trade facilitation arrangements, in particular customs clearance facilitation. In order to bring mutual benefits to Guangxi and ASEAN in trade and investment, the autonomous region takes the lead in studying and implementing the “two countries, one inspection” system for customs clearance facilitation with ASEAN countries.