Chinese Mainland

By Ulrike Solmecke, Department of International Political Economy of East Asia/Ruhr-University Bochum

Introduction

The New Silk Road or the 'One Belt, One Road' (OBOR) initiative aims at nothing less than creating a comprehensive trading network across three continents – Asia, Europe and Africa – thereby integrating around 60 countries with a total of about 63 per cent of the global population, presently generating 29 per cent of worldwide GDP (Wang 2014). The concept of the '21st Century Maritime Silk Road' as a means to intensify China's maritime cooperation with Asian countries and to develop new trade routes via Africa to Europe was introduced in October 2013 by the Chinese president in a speech at the Indonesian parliament…

The Influence of Multilateral Financing Institutions: The Example of AIIB

Important additional performance regulations come from the financing institutions. All financing institutions involved in the OBOR initiative provide regulatory frameworks that address environmental goals; the most comprehensive has been formulated by the AIIB (Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank). Its Environmental and Social Framework (AIIB 2016a: 14) requires, inter alia, private and public clients to undertake environmental and social assessments, including evaluations of environmental data and risks as well as prescribing monitoring and reporting measures for ongoing projects to ensure compliance with the framework. These regulations are complemented by an exclusion list, which expressly precludes the financing of socially or environmentally harmful projects (AIIB 2016a: 46-47). On the whole, the formulation of the guidelines nonetheless leaves considerable room for manoeuvre. They allow for mitigating, offsetting and compensating for adverse impacts, and so on. Being firmly committed to the principles of green growth, the regulations aim to deal as effectively as possible with negative effects, without losing the primary focus on economic growth. While supporting environmentally sounder behaviour among clients, and thereby providing comparatively soft regulatory push, the guidelines cannot be expected to encourage the waiving of unsustainable practices on this basis.

Particularly in connection with multinational transport and construction infrastructure providers, the envisaged AIIB Energy Strategy could theoretically be an important instrument as the energy mix promoted in this context could have a substantial and direct impact on the CO2- intensity of the project units. But here again, the effectiveness of the guidelines depends on the actual strength of the focus on sustainable energy sources. The preliminary issues note (AIIB 2016b) provides for the support of renewable energy, but does not exclude active support of technically advanced fossil fuel based energy production. Push impacts to adopt major sustainability-relevant innovations are restricted within the broad limits of the issues note, thus limiting the immense potential of the regulating strategy.

Conclusion

In sum, economic pressure for European and Chinese multinationals to leave the current path due to slower economic growth in China and a weak economy in the eurozone is apparent as a potential push factor. Investing in 'green economy' strategies as an alternative to business as usual holds forth the promise of economic success. This does not, however, really translate into a need to profoundly change routines or to embark on innovative paths for the industry sectors addressed in this article. One reason is that current stimulus programmes, especially the OBOR initiative, maintain the prospect that a fundamental shift will not be necessary.

Moreover, against the background of enormous demand, particularly as many Asian and European regions are under pressure to catch up economically, the lack of orientation towards sustainable development objectives is unlikely to negatively influence the economic success of the companies involved. The main incentives generated by the OBOR initiative focus on economic growth. Although there are also some environmental goals, they are generally assumed to be compatible with economic growth targets. Without exception, for the industry sectors considered here this results in environmental goals ranking second to efforts to stabilize and promote economic parameters.

Ecological improvements that are triggered by national provisions or self-regulatory initiatives certainly improve environmental performance but they do not bring about structural change. Past experience has clearly shown that quantitative innovations incur a high risk of rebound effects – which are in this case very likely to arise, given the scope of the envisaged project. Multilateral financing institutions generally have great potential to stimulate behaviour changes. But as the example of AIIB shows, these potentials rarely reach fruition; environmental frameworks aiming at innovation push are provided, but they leave much scope for companies to remain on unsustainable paths.

Ultimately, both push and pull factors within the framework of governance arrangements remain weak, as in the preceding discussions of the transport and cement industries. A change of the modal split or a shift towards more environmentally sound building materials are therefore not to be expected on the basis of currently available governance instruments. Instead, institutional regulation and incentive systems support minor 'green' changes but have – on the whole − a rather reinforcing effect on the orientation towards conventional development paths for the multinational enterprises involved in the OBOR project.

Please click to read the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By CGCC Vision

The “Belt and Road” initiative has been facilitating the connection of infrastructures and the integration of trade, industries and finance amongst countries along the Belt. All these aspects have pressing demand for professional services. With its international acclaim for professional services, how can Hong Kong secure a share from the abundant opportunities of the “Belt and Road” ?

Linda Li: Hong Kong’s professionalism to build China’s soft power

“As the country develops its hard power, attention should also be placed on national soft power, which could constantly enhance the comprehensiveness of the country’s overall development.” China President Xi Jinping has emphasized on many occasions that the integrated strength of nationals comprises both hard and soft power. At present, the “Belt and Road” is the grandest national strategy of China. The country must continue to build its soft power to promote collaboration amongst “Belt and Road” countries and to strengthen the mutually beneficial relationship of the parties involved.

Linda Li, Professor of the Department of Public Policy of City University of Hong Kong wrote analysis regarding Hong Kong’s positioning under the national strategy of “Belt and Road”. She proposes that Hong Kong should use its professional service advantage to contribute to the country’s soft power. Lately, she and her research team have received a grant from the Strategic Public Policy Research Funding Scheme of the Central Policy Unit of the HKSAR Government. They will study the role and the sustainable development of Hong Kong’s professional service industry in the “Belt and Road”. The study also organizes and constructs “Sustainable Hong Kong Research Hub”, a cross-disciplinary application research platform that connects universities and local industries.

An amicable lion equipped with both soft and hard powers

What is soft power? Li explained that soft power tends to be an academic concept. “The so-called soft power is a notion relative to hard power. What is hard power? In ancient times, when there were conflicts of interests or when there were differences in beliefs, disagreements were usually solved with armed forces – the strong won and the weak lost. In the modern world economic sanctions are used instead of waging wars to solve similar problems.”

To put it simply, hard power refers to military power and economic strength. Li commented, “Soft power is the opposite. It is neither military nor financial. Rather, it is all about attractiveness. If we use making friends as an analogy, those who associate with you because they are afraid of your force can hardly be called friends; neither can those tempted by your financial strength be considered a friend. Only those who truly like to be with you, who are attracted by your charm, can be called friends.” From the perspective of international politics, the outcome of nurturing Chinese soft power is to build the cultural substance and image appreciated by other countries, which can in turn help to create a stronger regional influence.

In March 2014 during Xi’s visit to France, the famous quote of Napoleon was mentioned, “China is a sleeping lion. When she wakes, she will shake the world. The lion is already wide awake, but it is a peaceful, amicable, and civilized lion.” Li believed that if China is to promote its “amicable, delightful, loveable and respectable” image through the “Belt and Road”, then Hong Kong can play a part in this aspect.

In a global soft power report published by Deloitte in 2016, Hong Kong’s soft power ranks the first amongst all Asian cities. The talents of Hong Kong have come from around the world. About 770,000 people from about 39 global locations are working in our knowledge-based industries. There are 3,491 institutes and enterprises around the world that has direct connections with Hong Kong; we are conducting business with 79 countries. Any companies coming to Hong Kong can easily find a cooperative partner who can meet their expectations.

Facilitating the signing of “Belt and Road” projects in Hong Kong

“We can imagine that there will be more and more commercial and large scale infrastructure projects related to ‘Belt and Road’ in the future. The agreements of these projects can be signed in Hong Kong, and contractual issues can be settled under Hong Kong’s legal framework.” Li added that with Hong Kong’s renowned and professional legal system, international markets are willing to entrust their projects to us and this is the soft power of Hong Kong . For a very long time, Hong Kong has been China’s window to the world. Ever since China’s reform and opening up, Hong Kong has been drawing foreign capital to invest in China. In the past ten years, Chinese enterprises are actively “going international”.

According to Li, soft power, as an economic appeal, usually comes from the country’s own cultural charisma. It is an art to demonstrate cultural charm in diplomatic communications and trade flows between two countries; the requirements would be much more complicated than common business dealings. Li sees that Hong Kong is already equipped with a culturally rich ambience. With its premium professional services, Hong Kong is poised to develop into a soft power hub in the “Belt and Road”.

Li also pointed out that every project involves risk, such as business risks, management risks, sovereign risks, etc; we must stay vigilant to all these risks. She noted that the best way to handle risks is prevention. “Compared to China, Hong Kong is more professional in terms of arbitration and mediation. The technicalities in this area have to be further strengthened, which can be leveraged on to prevent many risks from “Belt and Road” projects in the future.”

The international legal framework for the “Belt and Road”

The legal bases of different countries vary. It is not uncommon that companies tapping into overseas market suffer as a result of the differences in legal perspectives. The same situation happens in China. Apple Inc, New Balance, and renowned former basketball player Michael Jordan, for example, have all had disputes in business law with Chinese companies and government authorities. Li highlighted that with many projects to launch under the “Belt and Road”, the money involved is inestimable. Therefore, the potential issues brought about by legal differences must first be clarified and understood. In fact, there have been proposals to develop an international model for commercial law, which can serve as the reference for judgement when disputes arise in cross-border businesses, and help to reach an agreement.

Li stressed that if China is to establish an international legal framework that can be adapted to the “Belt and Road”, the risks of different business transactions should first be considered. “Under the wider context of “Belt and Road”, we can foresee that the signing parties of certain mega projects will not be enterprises, but rather governments. Some accidents of the same kind took place in the past – as a new term government in a country took over power, the new government did not follow the path of the previous one and invalidated many contracts signed by the previous term. This kind of sovereign risk must be considered when the international legal framework is constructed.” Li believed that as Hong Kong is a robust legal center, it should take a more active role in this aspect of “Belt and Road” affairs. Hong Kong can first begin to conduct preliminary research to measure the risks of “Belt and Road” countries and to prevent high-risk time and locations.

Li emphasized that the professional services of Hong Kong will be adorning the world-facing “Chinese brand” by increasing the country’s resilience against risks. This in turn can lift Hong Kong’s international reputation to a new level, demonstrating the unique advantage of its “One country, Two systems”.

P C Lau: Professional Sectors Have Great Potential under the “Belt and Road Initiative”

When asked about what opportunities the “Belt and Road” Initiative would offer to Hong Kong’s professional services, many members of the professions would tell you capturing these opportunities are easier said than done. P C Lau, Chairman of the Hong Kong Coalition of Professional Services, visited some “Belt and Road” countries to observe and study on site. He has had an in-depth look at how the local professional sectors can tap and expand into the “Belt and Road” markets.

Hong Kong professional services to fill the gap

Lau commented that in the face of a complicated and everchanging global situation, China can no longer merely follow the footsteps of European countries and the US; rather, it is time to create its own rules of the game. The Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank, the Silk Road Fund, and the free trade agreement between China and the ten ASEAN nations are all rising to this opportunity. The strategy of the “Belt and Road” has been put forward under this backdrop.

“About 40% of the world’s population lives along the “Belt and Road”. At present, the aggregate GDP of these countries is not

high, implying they have much potentials awaiting uncovering.” As a member of “old Hong Kong”, Lau frankly commented that Hong Kong has a wide array of strengths. “The fact that Hong Kong has long been an international free port is its primary strength. In terms of social structure, ‘One Country, Two Systems’ is another strength. As a starting point of the Maritime Silk Road, we also have a favorable geographical location. Our free flow of information, talent pool, sound legal system and business ethics also offer confidence to other countries.” He emphasized that Hong Kong’s services are highly professional, and we have the capacity to deliver premium professional service offerings – something that are still lacking in “Belt and Road” countries.

Keeping up with state enterprises in generating business opportunities

Earlier on, Lau visited Kazakhstan, Myanmar, Indonesia, Cambodia and Yinchuan in Ningxia Autonomous Region. He has much to share about choosing which “Belt and Road” country to tap into and the points to note in doing so.

What tips can the Hong Kong professional service sectors use when they expand into the “Belt and Road” markets? Lau responded, “State enterprises and central state-owned enterprises.” He pointed out that basically speaking, when Hong Kong professionals take part in the projects of state enterprises and central state-owned enterprises, they would be able to offer services and collect fees under very low risks. That said, Hong Kong companies should try not to be “too greedy”. They should focus on certain markets with high potentials. “Do not make plans to profit from local companies, but rather from state enterprises and central state-owned enterprises. To put it simply, look for businesses that are settled in USD or RMB instead of the local currencies. This would help prevent currency devaluation risks.”

Lau encouraged Hong Kong’s professional service industry to make good use of their prevailing networks. There are many clansmen associations as well as commercial and industrial associations in “Belt and Road” countries. If we can leverage on our connections with them, we will be able to get a head start. “I recall a few years ago during the Malaysian delegation led by the then Chief Secretary Carrie Lam, she met with Hong Kong expatriates living in the country. Most of them are engineers, which show that Hong Kong has been exporting many professionals.”

Business opportunities are certainly enticing, but Lau also pointed out that to expand into the “Belt and Road” markets, a series of issues must first be overcome. Those who are interested should find out what these are and make early preparation. “The first and foremost are the cultural differences: many Central Asian countries, such as Kazakhstan, are Muslim and there are many taboos. Secondly, there are market risks: for example, the new term of Myanmar government vetoed a reservoir project that was previously approved. Then, there are customer risks: for example, there may not be a local organization comparable to a credit insurance unit. In case something goes wrong, customers would not be protected.”

Despite these shortcomings, Lau still encourages Hong Kong’s professional service sectors to get an early start in these places. Earlier on, he went on a trip to observe and study a few European countries, including Hungary, Poland and Germany, and saw that quite many Mainland enterprises have already tapped into them. They began with an annual profit of USD 3 to 4 million, but are now about 10 times bigger; profits are growing by tens of millions. These countries have good relationship with China. Hong Kong companies can ride on this and offer their professional services.

Drawing on others’ experience to gain a head start

From his trip to Kazakhstan last year, Lau learned that the country had plans to construct a 65km light rail. The China Development Bank has offered a loan of USD 1.8 billion, and a Spanish company will be supplying the trains. China Communications Construction Company and China Railway Construction Corporation are both ready to jump in. All hardware elements are set, but management expertise is lacking. In the end, they seek help from MTR Corporation of Hong Kong for professional assistance.

Over the past few years, MTR’s businesses have expanded into Mainland cities such as Beijing, Tianjin, Shenzhen, etc. Airport Authority Hong Kong also took part in the construction of Zhuhai Airport and Hongqiao Airport. Much experience has been accumulated in these former success cases, which could serve as a reference for companies planning to tap into the “Belt and Road” markets.

Lau quoted Zhang Dejiang, Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, who spoke about two infrastructure projects in Nepal and Cambodia in the “Belt and Road” Summit held in May 2016 in Hong Kong. Hong Kong consultancy firms were introduced to these two projects to undertake supervision duties. Soon after, Nepal was hit by a large earthquake. Many buildings collapsed, but not those supervised by Hong Kong companies. These fully illustrate the fine quality of Hong Kong’s professional service.

Government should assume leading role

Lau said that as the government has always pursued the consistent principle of “small government, big market”, there are worries that any industry-specific support would be criticized by other industries. However, he considers this approach inadequate under current circumstances. He wished that the government could serve as the industry’s lobbyist and connector – as there may be cases that when opportunities arise in mega-scale business projects, government to government negotiation is required to close the deal. Lau hopes the government can change its way of thinking and actively assist the industries in looking for new business opportunities, rather than simply relying on the industry’s own efforts.

This article was firstly published in the magazine CGCC Vision March 2017 issue. Please click to read the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Peter Cai, Lowy Institute for International Policy

Implementation Challenges: Lack of Bankable Projects and Moral Hazard

Chinese leader Xi Jinping launched OBOR at the end of 2013. Three coordinating government agencies (the National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Ministry of Commerce) issued the first official blueprint on OBOR, the ‘Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road’, just two years later in March 2015. However, there has been slow progress in terms of the implementation of projects outside of China.

At a recent OBOR work conference chaired by Vice-Premier Zhang Gaoli, a member of the Politburo Standing Committee who is overseeing the initiative, Xi urged for some signature projects to be implemented quickly, showing tangible benefits and early success. He wanted the focus to be on infrastructure projects that improve connectivity, deal with excess capacity, and trade zones. “We need to get some model projects done and show some early signs of success and let these countries feel the positive benefits of our initiative”, he told a large gathering of senior party officials and business people. Xi is not happy with the lack of progress, not least because OBOR is part of his political legacy. But the initiative faces multiple, formidable challenges.

First, there is a significant lack of political trust between China and a number of important OBOR countries. Perhaps the best example of this is India. The country’s Foreign Secretary Subrahmanyam Jaishankar has said OBOR is a unilateral initiative and that India would not commit to buy-in without significant consultation. Sameer Patil, a former assistant director at the Indian National Security Council and a researcher at foreign policy think tank Gateway House, says the China– Pakistan Economic Corridor project is a major obstacle to Indian involvement in the initiative.

A second problem is that nearly two-thirds of OBOR countries have a sovereign credit rating below investable grade. Some key OBOR countries such as Pakistan are unstable, which poses significant security risks to Chinese companies as well as personnel working there. The Pakistani military has, for example, promised to raise a special military unit of 12 000 soldiers to protect China–Pakistan Economic Corridor projects.

A third problem is caution on the part of over-leveraged and risk-averse Chinese financers. After Xi announced OBOR, Chinese state-owned financial institutions followed with a raft of policies that echoed the president’s grand vision. China Development Bank, which is expected to play a key role in financing OBOR, says it is tracking more than 900 projects in 60 countries worth more than US$890 billion. Bank of China, which has the largest overseas networks, pledged to lend US$20 billion in 2015 and no less than US$100 billion between 2016 and 2018.56 Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) has been looking at 130 commercially feasible OBOR-related projects worth about US$159 billion. It has financed five projects in Pakistan and has established a branch in Lahore.

Yet, despite these public pledges of support, many Chinese bankers and especially those from listed commercial banks such as ICBC are concerned about the feasibility of OBOR projects. They are worried about the many risks associated with overseas loans, including political instability and the economic viability of many projects. As Andrew Collier, Managing Director of Orient Capital Research, has noted: It is pretty clear that everyone is struggling to find decent projects. They know it’s going to be a waste and don’t want to get involved, but they have to do something.” Collier gave an example of one Beijing bank that he said had stopped lending to rail projects in risky places such as Baluchistan in Pakistan.

A chief investment officer from one of China’s largest state-owned financial institutions also told the author about his own reservations: “I prefer to invest in places like Canada and Australia, where I can get safe and decent returns. However, where I have been ordered to invest in OBOR countries, I will only allocate the minimum amount.”

The reservations of Chinese financiers and businesspeople about OBOR also need to be seen in the context of the worsening debt problem within China’s financial system, especially the number of non-performing loans on banks’ balance sheets. This rapid pile-up of debts took place after the country’s massive stimulus package of 2008. China’s leading business magazine, Caixin, has suggested that OBOR could produce a repeat of 2008. Influential economic policymakers in China are also concerned that the political impetus behind OBOR could drive China into investing in white elephant projects abroad. They are worried that some countries will take advantage of OBOR and sign up to Chinese projects with no intention of repaying the loans.

Yiping Huang, an influential economist who sits on the Chinese central bank’s monetary policy committee and a former investment banker, has argued that China needs to proceed cautiously on OBOR projects: “The most effective way to promote the initiative is by getting one or two projects done. If they turn out to be effective, it will be easier to take the next step. If early projects are disastrous, the future path will be hard.”

Huang has also noted the efforts to develop the country’s western region largely failed because the state ignored the fundamental economic issue of ensuring a return on assets.

There are indications that Chinese financiers are demanding tougher terms to ensure OBOR projects are financially viable over the longer term. Negotiations with the Thai Government over the building of a high-profile rail project were hamstrung by disagreements over interest rates, among other things. Chinese financiers demanded a 2.5 per cent return on their concessional loan while the Thai Government wanted 2 per cent, the same rate Beijing offered to Jakarta. When Chinese bankers insisted on 2.5 per cent Bangkok said it would finance the project itself. Xue Li, a senior researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and a member of a semi-official OBOR expert panel, says China is likely to lose money on the Indonesian high-speed rail deal, which Beijing is treating as a one-off special case and does not want the generous funding terms to become the norm.

Conclusion

OBOR is President Xi’s most ambitious foreign and economic policy initiative. Much of the recent discussion has concerned the geopolitical aspects of the initiative. There is little doubt that the overarching objective of the initiative is helping China to achieve geopolitical goals by economically binding China’s neighbouring countries more closely to Beijing. But there are many more concrete and economic objectives behind OBOR that should not be obscured by a focus on strategy.

The most achievable of OBOR’s goals will be its contribution to upgrading China’s manufacturing capabilities. Given Beijing’s ability to finance projects and its leverage over recipients of these loans, Chinese made high-end industrial goods such as high-speed rail, power generation equipment, and telecommunications equipment are likely to be used widely in OBOR countries. More questionable, however, is whether China’s neighbours will be willing to absorb its excess industrial capacity. The lack of political trust between China and some OBOR countries, as well as instability and security threats in others, are considerable obstacles.

Chinese bankers will likely play a key role in determining the success of OBOR. Though they have expressed their public support for President Xi’s grand vision, some have urged caution both publicly and in private. Their appetite to fund projects and ability to handle the complex investment environment beyond China’s border will shape the speed and the scale of OBOR. There is a general recognition that this initiative will be a decade-long undertaking and many are treading carefully.

Please click to read the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

East European nation hopes to resume mainland poultry exports and find key role within the Belt and Road Initiative.

Polish poultry producers are hoping to resume exports to China by the end of this month. Poultry imports from Poland to the mainland were banned in December last year following outbreaks of bird flu on farms in the west and south of the country.

Technically, imports cannot resume until three months after the last reported case of the avian influenza strain in the country. Poland has, apparently, been free of infection since 15 March this year.

Discussions as to the resumption of such exports were held in Hong Kong in early May. Leading the talks were representatives of Poland's National Poultry Council (KRD), with a number of leading mainland poultry distributors in attendance.

A recent rise in Poland's poultry production levels has seen the country keen to secure new export destinations, with China regarded as one of the most promising of the international markets. Overall, sales to the mainland are particularly valued, given that certain poultry items – most notably chickens' feet – have a ready market in China, while being virtually unsalable elsewhere.

According to the KRD, should exports resume, the total value of the Poland-China poultry trade could exceed US$560 million a year by 2020. Immediately prior to the ban, Polish poultry exports to the mainland were valued at about $84 million annually.

According to the KRD, Poland is emerging as one of the EU's key poultry-production centres. At present, it produces about 2.5 million tonnes of poultry a year, 40% of which is exported. Approximately 80% of all such exports currently go to other EU member nations.

In other moves, the Polish government has high hopes of playing a significant role in China's Belt and Road Initiative. In particular, it is hoping that the mooted Central Polish Airport (CPA) project could form an integral element of China's plans to enhance its European trading routes.

In addition to air-cargo transport, the CPA initiative would also see the construction of fast rail links, integrated transport corridors, dedicated economic zones and a comprehensive upgraded to the region's energy infrastructure. In light of its potential significance to the overall BRI programme, Poland is believed to be seeking funding from the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank in order to help make the planned CPA a more affordable reality.

At present, Poland, which is pitching itself as China's gateway to Europe, has been keen to nurture its trading relationships with the mainland. In particular, it has been promoting opportunities relating to a number of niche investments, including yachts and designer furniture, while also looking to secure joint opportunities with regard to environmental technologies, medical and mining equipment, cosmetics and the IT sector.

Anna Dowgiallo, Warsaw Consultant

Editor's picks

Trending articles

China has become a major trading country and important source of foreign investment around the world as its economic activities with other countries continue to grow. Under the Belt and Road development strategy, Chinese enterprises have stepped up their efforts in “going out” to engage in trade and investment activities in countries along the Belt and Road routes. This has spurred demand for professional services to support these enterprises' growing international business.

China’s coastal areas, including the Pearl River Delta adjoining Hong Kong and the Yangtze River Delta (YRD), have always been major areas for economic co-operation with foreign countries. More and more enterprises in Shanghai and the adjacent areas have been heading for the Belt and Road regions in search of opportunities to boost the development of their businesses.

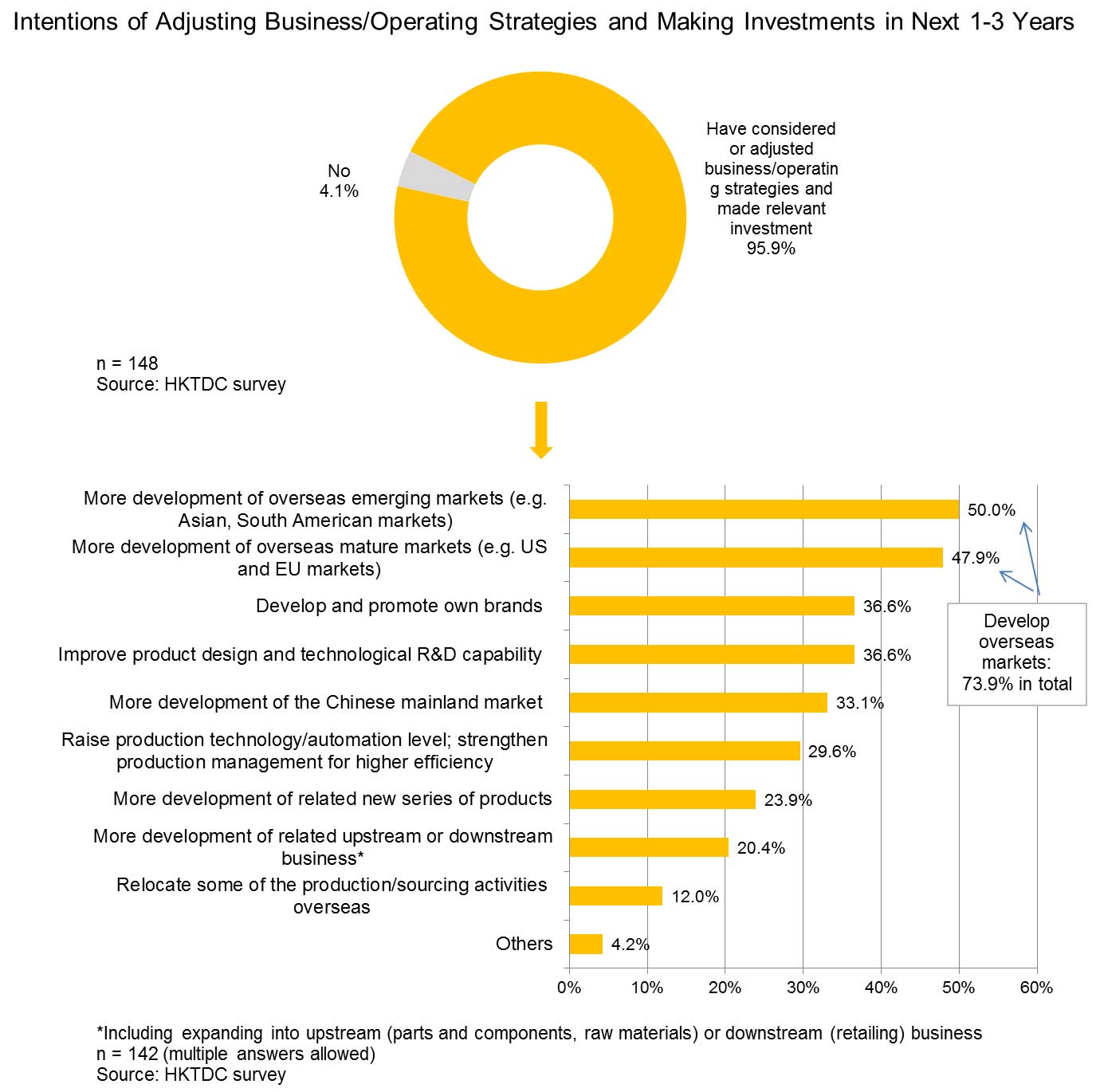

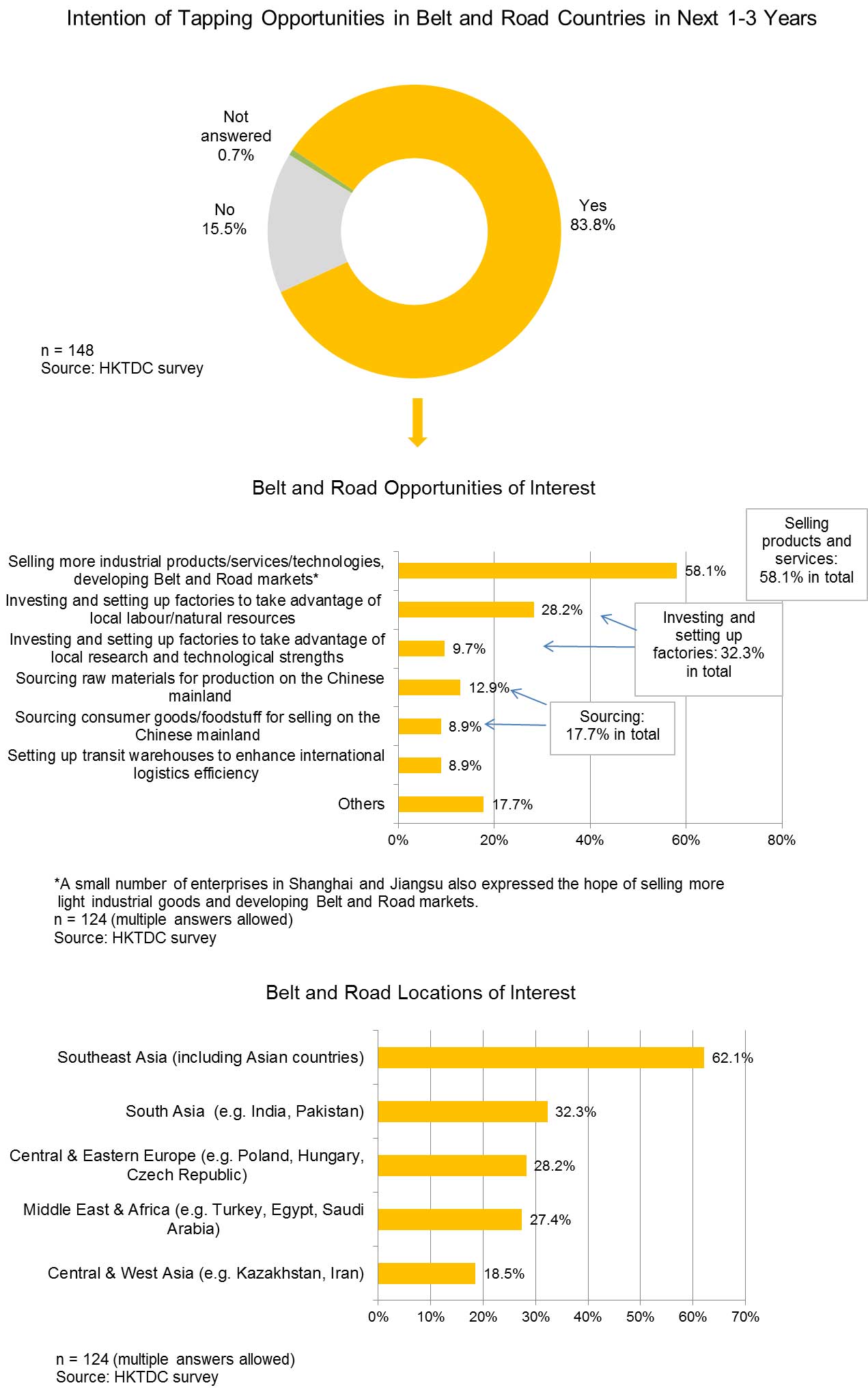

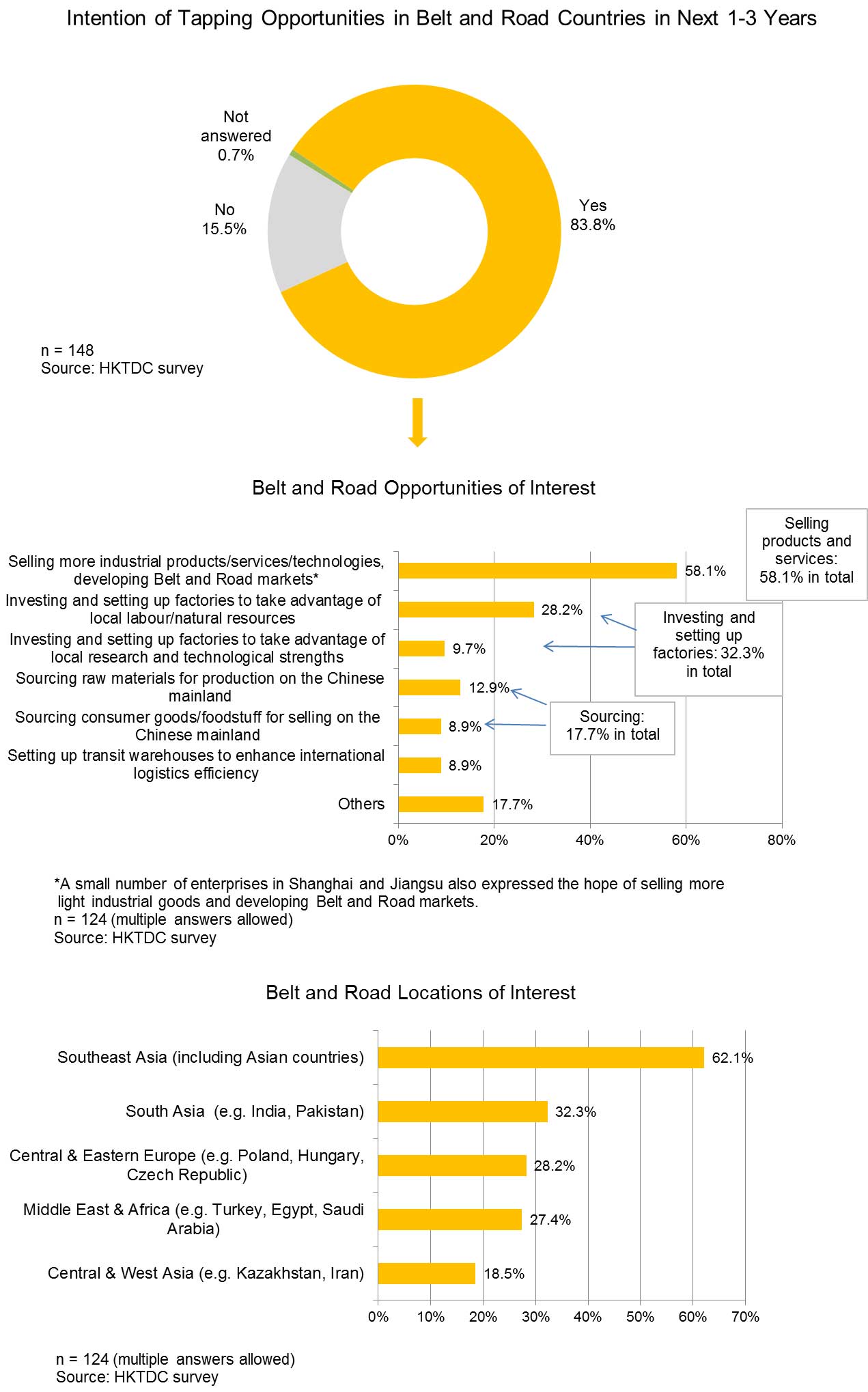

HKTDC conducted a questionnaire survey in Shanghai, Jiangsu and other places in the YRD in the first quarter of 2017 to gauge the situation. The survey results indicate that the great majority of domestic respondents (84%) would consider tapping business opportunities in Belt and Road countries in the next one to three years. Among these, many enterprises (46%) said that Hong Kong was their preferred destination for seeking professional services outside the mainland for capturing business opportunities. This matches with the findings of a similar HKTDC survey in South China last year. [1]

The Belt and Road destinations that respondents showed the greatest interest in were Southeast Asia (62%), South Asia (32%), and Central/Eastern Europe (28%). Most enterprises (58%) expressed the hope of selling more industrial products, relevant services and technologies to Belt and Road markets, while one in three (32%) would consider investing and setting up factories in Belt and Road countries.

There is no doubt that Hong Kong is the preferred platform for mainland enterprises “going out” to invest overseas. Hong Kong service providers have been helping mainland enterprises handle their trade and investment businesses in Hong Kong and overseas markets for many years. Further efforts by mainland enterprises, including those in the YRD, to tap Belt and Road opportunities are bound to generate more business for Hong Kong. (For more details on China’s foreign investment and Hong Kong as the preferred platform for mainland enterprises “going out” to invest overseas, see: China Takes Global Number Two Outward FDI Slot: Hong Kong Remains the Preferred Service Platform)

Belt and Road: Hotspot for China’s Foreign Trade and Investment

China has become a major world economy and the economic activities of Chinese enterprises abroad have gradually extended from trade to other fields of investment. China’s foreign trade volume stood at US$3.69 trillion in 2016, second only to the US with US$3.71 trillion. [2] During the same period, China’s foreign direct investment (FDI) flows (excluding financial sector investment) reached US$170 billion [3], which was among the highest in the world and exceeded foreign capital inflow. It is now a country with net capital outflow.

China’s trade and investment in Belt and Road countries will see sustained growth particularly under the Belt and Road initiative and development strategy. Figures released by the Ministry of Commerce showed China’s total trade with Belt and Road countries rose by 0.6% to RMB6.3 trillion (equivalent to US$1 trillion) in 2016, accounting for just over a quarter (26%) of China’s total foreign trade during the period. Direct investment made by Chinese enterprises in non-financial sectors in 53 Belt and Road countries totalled US$14.53 billion, accounting for 8.5% of China’s total non-financial FDI during this period. Most of the investment went to Singapore, Indonesia, India, Thailand and Malaysia.

As China gears up for the Belt and Road development strategy and encourages businesses to develop trade and investment with the countries and regions concerned, the Belt and Road initiative has become an important factor in driving the “going out” of Chinese enterprises for all kinds of economic activities. As Hong Kong has consistently been the preferred service platform for these enterprises [4], the development of the Belt and Road initiative is expected to spur demand for various Hong Kong support services from mainland enterprises.

HKTDC joined hands with the Shanghai Municipal Commission of Commerce in conducting a questionnaire survey among related enterprises in Shanghai and Jiangsu of the YRD in the first quarter of 2017 to find out about the challenges facing mainland enterprises in the region, their transformation, upgrading and investment strategies, their intention of “going out” to capture Belt and Road opportunities, and their demand for related professional services.

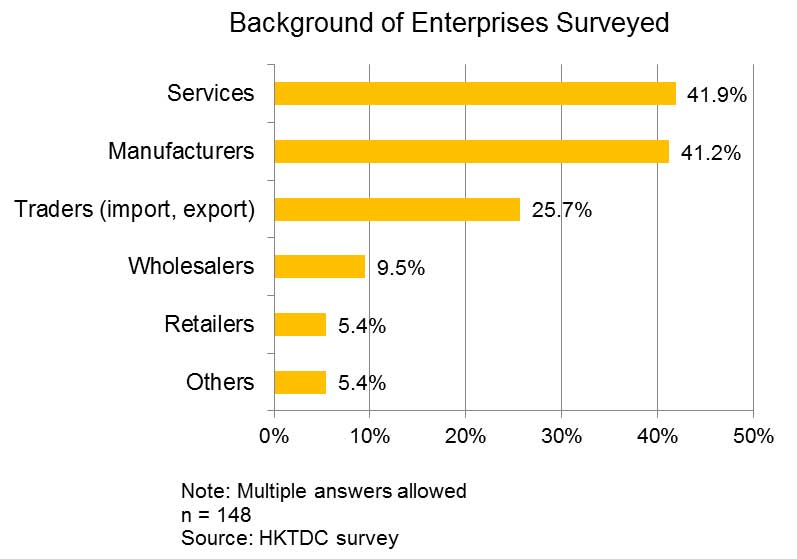

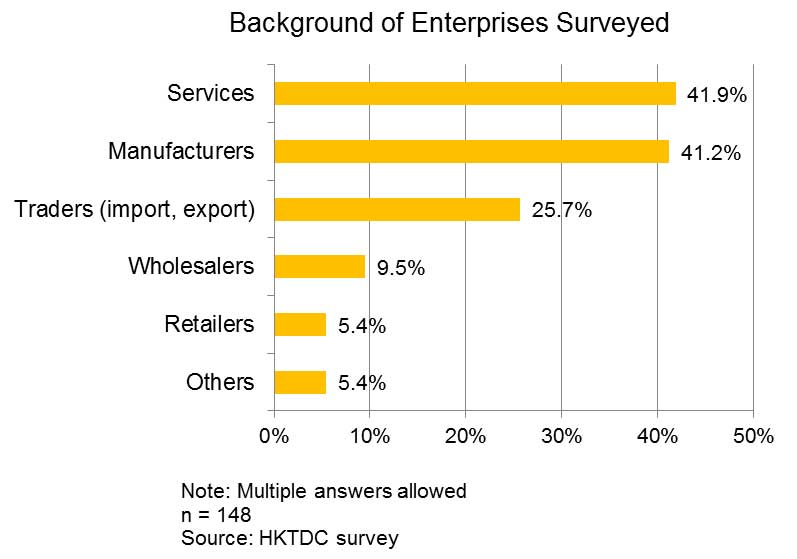

This survey was similar to the one conducted by HKTDC in South China in 2016. [5] A total of 163 completed questionnaires were collected. Of these, 148 were completed by mainland enterprises, including service suppliers, manufacturers and traders. What follows is a summary of the views expressed by these 148 mainland enterprises on “going out” to capture Belt and Road opportunities.

Challenges in Business Operation

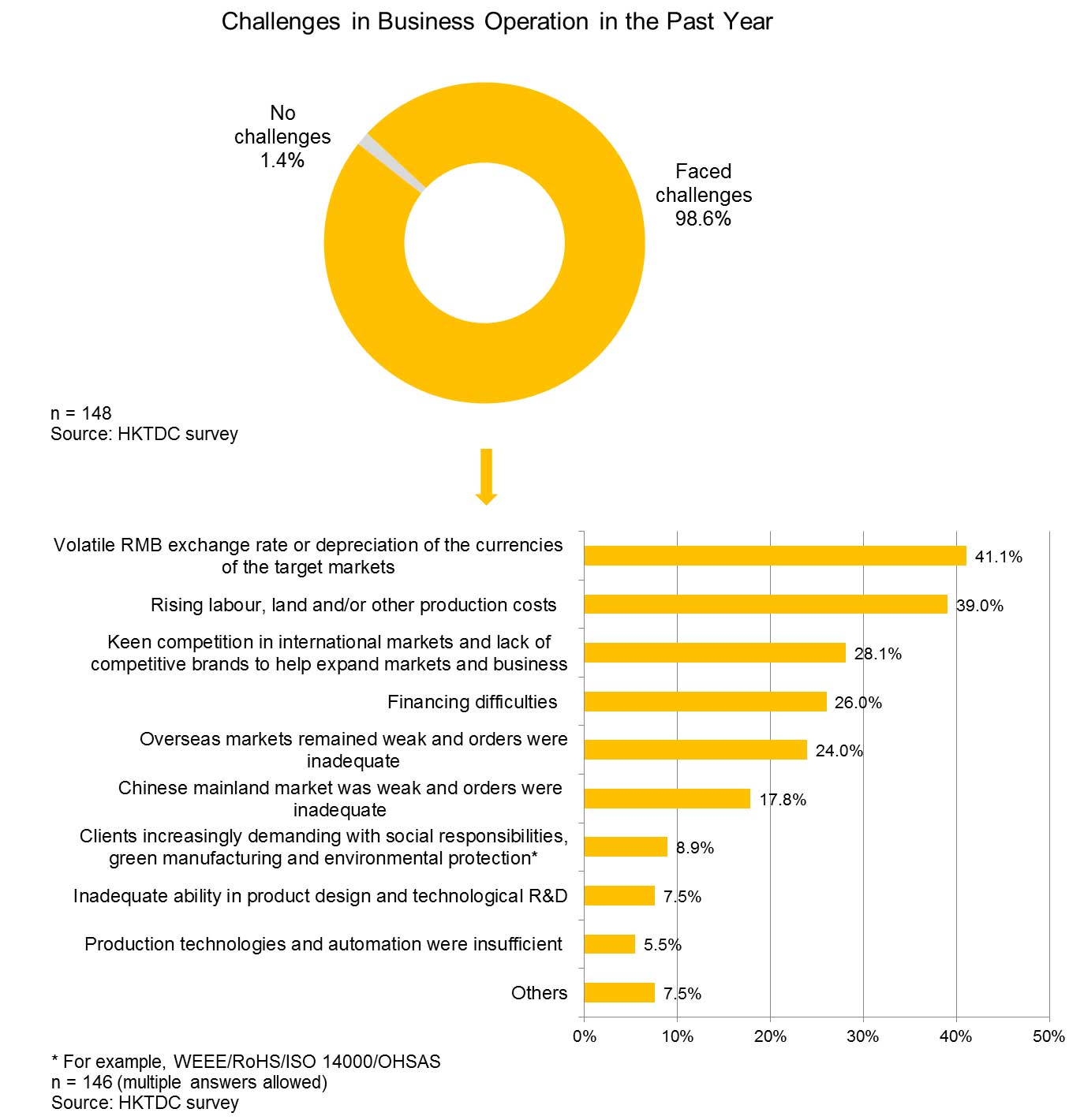

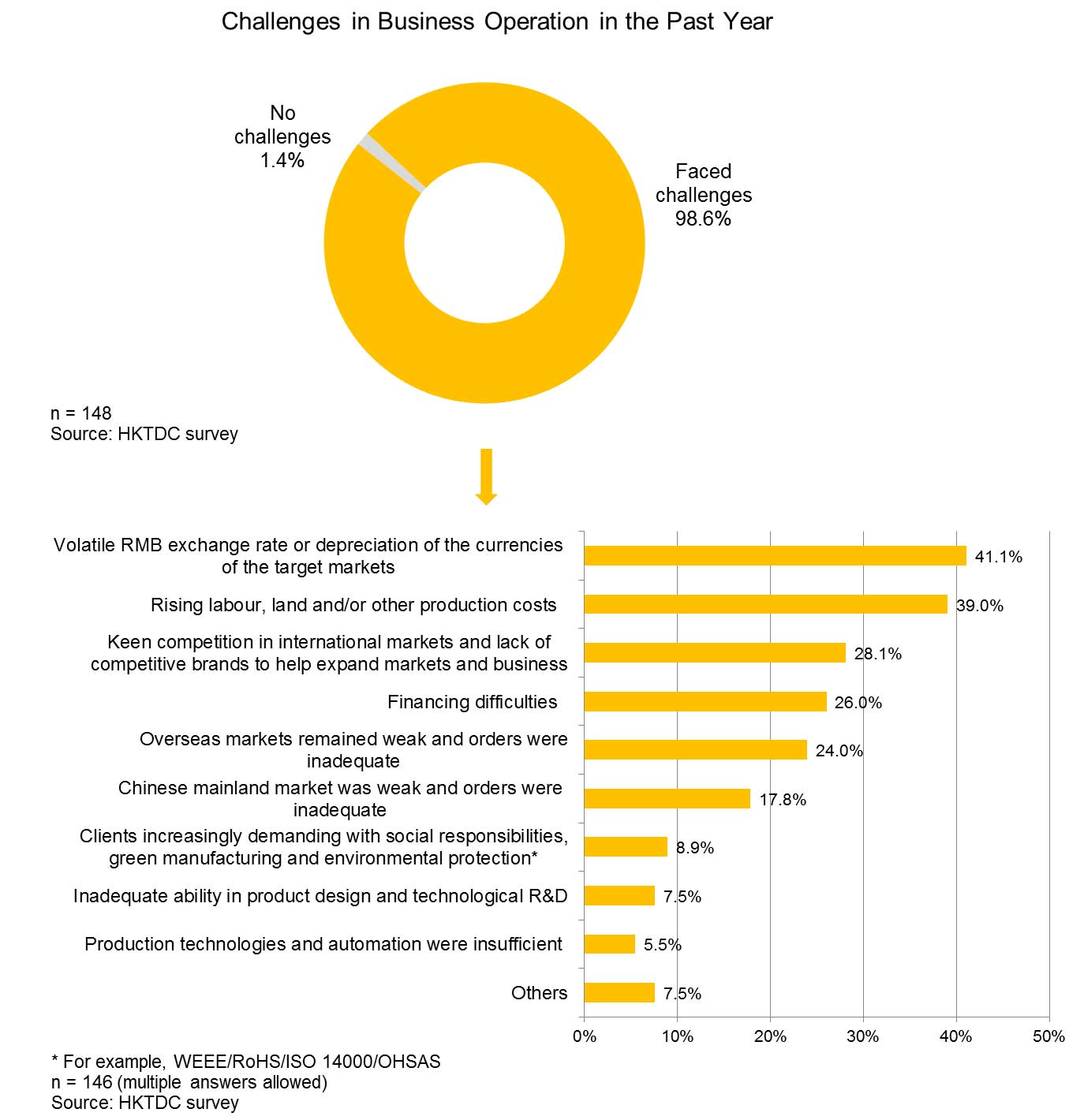

Virtually all respondents (99%) said that their business operations faced a variety of challenges over the past year. Their foremost concerns were the volatile RMB exchange rate (41%) and rising labour, land and/or other production costs (39%). Other challenges included keen competition in international markets (28%), financing difficulties (26%) and weak overseas markets and inadequate orders (24%).

Most Important Countermeasure: Develop Overseas Markets

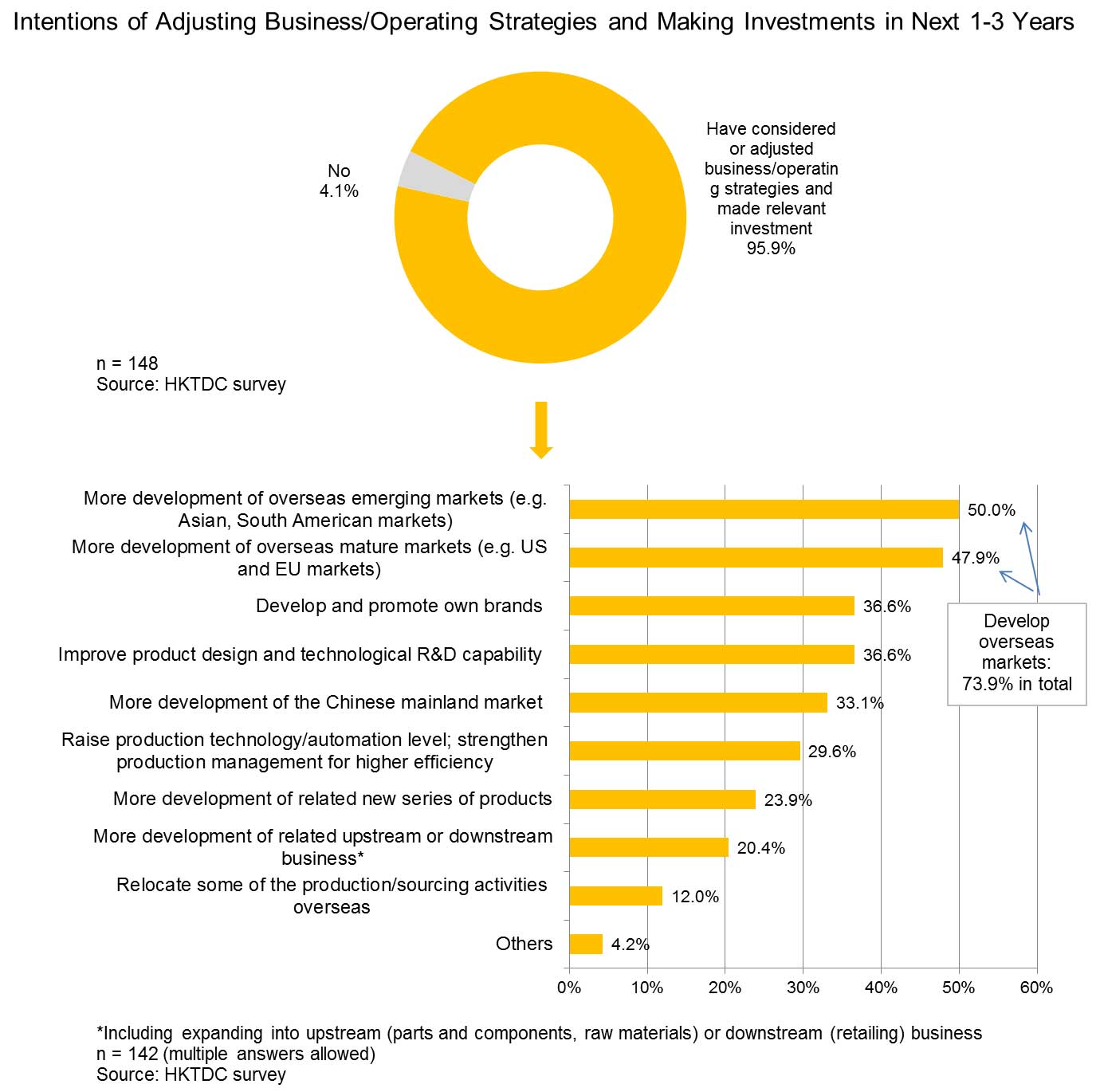

In order to tackle these challenges, over 95% of the respondents said either they would consider adjusting their business/operating strategies and making relevant investment in the next one to three years or they had already done so. Almost three out of every four (74%) of the respondents said they would first exert themselves to develop overseas markets. Of these, half (50%) said they would develop further overseas emerging markets and 48% said they would focus on overseas mature markets. More than one in three (37%) said they would develop/promote their own brands, while the same number said they would work on the improvement of product design and technological R&D capability.

Belt and Road Opportunities: Focusing on Southeast Asian Markets

As China continues to promote the Belt and Road development strategy, 84% of the respondents said they would consider tapping business opportunities in Belt and Road countries in the next one to three years.

Among those enterprises that would consider tapping Belt and Road opportunities, most said they wanted to sell more industrial products and related services and technologies to the Belt and Road markets. Just under a third (32%) said they wanted to go to Belt and Road countries to invest and set up factories for production, while 18% said they would like to go to source consumer goods/foodstuff for selling on the Chinese mainland and source raw materials for production on the Chinese mainland. Another 9% said they hoped to set up transit warehouses in Belt and Road countries to improve their international logistics efficiency.

Among those enterprises interested in tapping opportunities in Belt and Road markets, almost two thirds (62%) said they would focus on Southeast Asia, including ASEAN countries. Fewer respondents chose other regions, with a third (32%) picking South Asia (32%), just over one in four going for Central and Eastern Europe (28%) and the Middle East and Africa (27%), and one in five choosing Central and West Asia (19%).

Although there is a slight difference between the preferences of the respondents in this survey and the one conducted in South China last year, the preferences for Belt and Road opportunities and locations of interest are similar, suggesting that most mainland enterprises have the same intentions of tapping Belt and Road opportunities, regardless of where they are based.

Comparison of Survey Findings in South China and YRD

| Opportunities of Interest | Survey in South China | Survey in YRD |

| Selling products | 88% | 58% |

| Investing and setting up factories | 36% | 32% |

| Sourcing | 35% | 18% |

| Setting up transit warehouses | 22% | 9% |

| Locations of Interest | Survey in South China | Survey in YRD |

| Southeast Asia | 83% | 62% |

| South Asia | 27% | 32% |

| Central & Eastern Europe | 24% | 28% |

| Middle East & Africa | 23% | 27% |

| Central & West Asia | 20% | 19% |

Source: HKTDC survey

Need to Seek Services Support

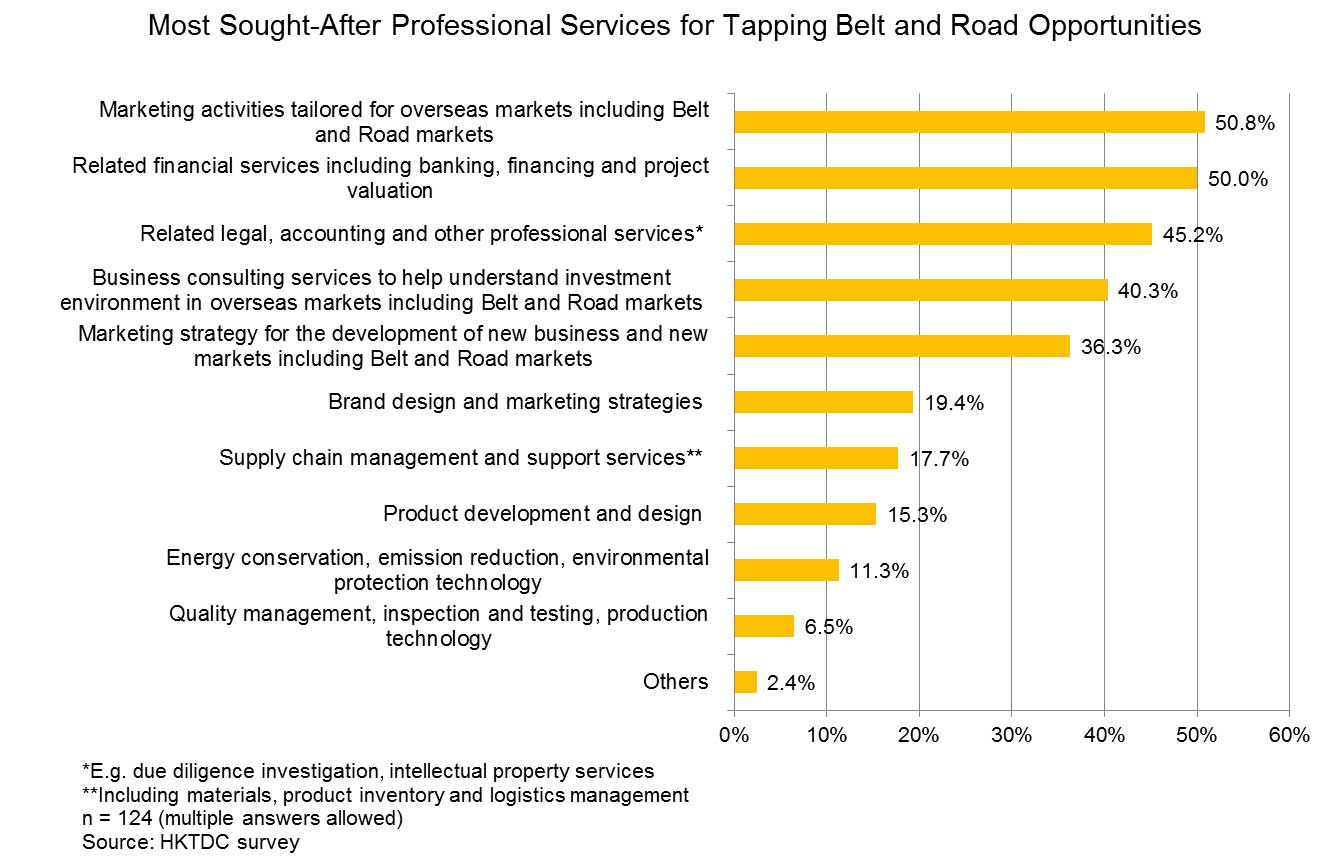

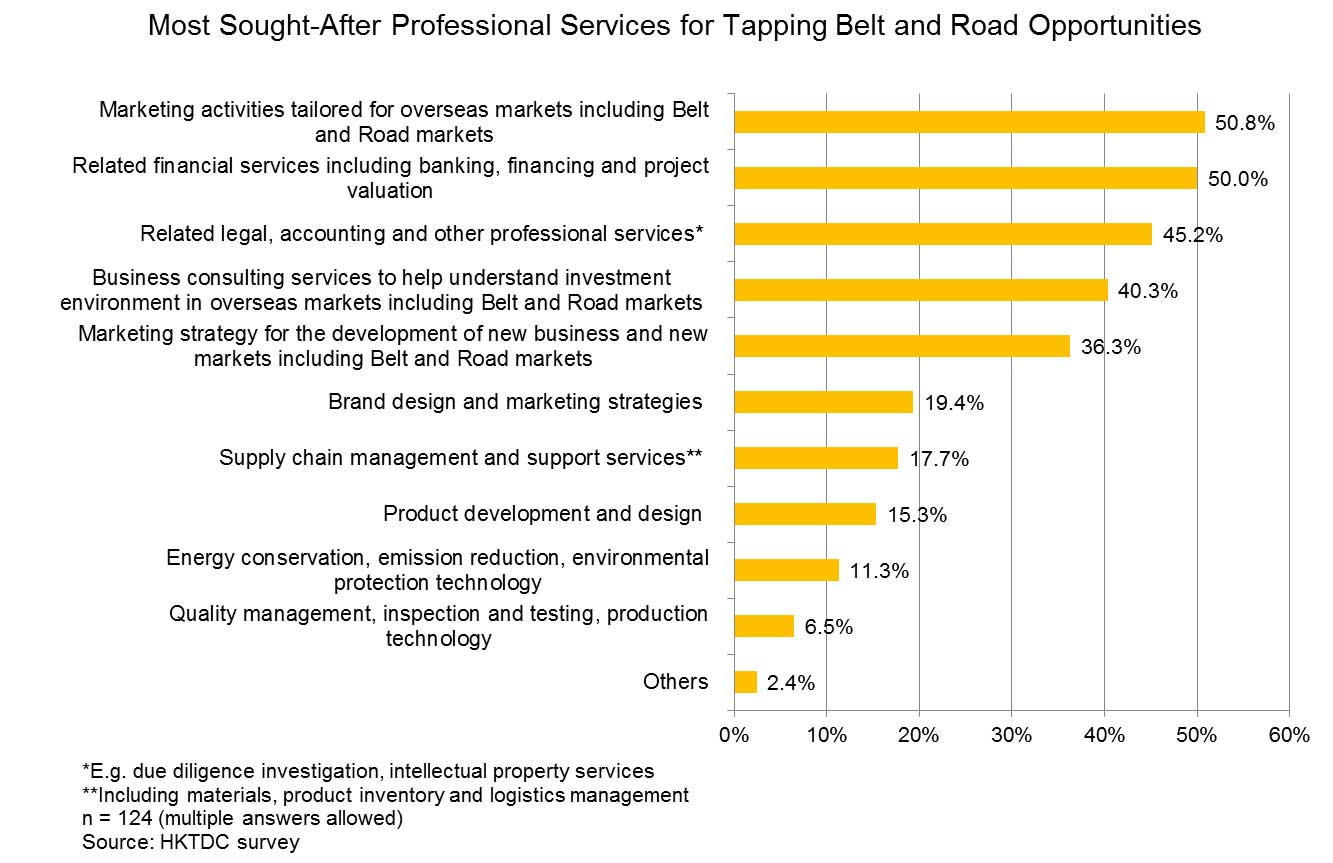

Of those enterprises looking to tap into Belt and Road opportunities, half (51%) said they would like to become involved in marketing activities tailored for Belt and Road and other overseas markets. Half (50%) said they would require related financial services, including banking, financing and project valuation. Just under half (45%) said they would like to seek related legal, accounting and other professional services. 40% said they would require business consulting services to help understand the investment environment in overseas markets, including Belt and Road markets.

Seeking Services Support in the Chinese Mainland and Hong Kong

In order to locate these aforementioned professional services, more than half (55%) of the respondents looking to tap Belt and Road opportunities said they would first source these support services locally. However, a significant number said they would also seek various professional services outside the mainland. Hong Kong was the most preferred destination for most enterprises, accounting for almost half (46%) of all respondents who would like to tap into Belt and Road markets. This again matched the findings of the survey conducted by HKTDC in South China last year. Other destinations highlighted as of interest included the US (34%), Germany (27%) and Singapore (23%).

HKTDC Research would like to acknowledge the help extended by the Shanghai Municipal Commission of Commerce in conducting the survey.

[1] For details about the survey in South China, please see: Chinese Enterprises Capturing Belt and Road Opportunities via Hong Kong: Findings of Surveys in South China

[2] Source: Customs Administration of China; World Trade Organisation

[3] Source: Ministry of Commerce of China

[4] On Hong Kong as the preferred service platform for mainland enterprises “going out”, please see: Guangdong: Hong Kong Service Opportunities Amid China’s “Going Out” Strategy, Jiangsu/YRD: Hong Kong Service Opportunities Amid China's "Going Out" Initiative, China’s “Going Out” Initiatives: Professional Services Demand in Bohai and China's “Going Out” Initiative: Service Demand of Western China to Tap Belt and Road Opportunities.

[5] Please see: Chinese Enterprises Capturing Belt and Road Opportunities via Hong Kong: Findings of Surveys in South China

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Jonathan Holslag, Vrije Universiteit Brussel

Abstract

For all the promises of mutually beneficial cooperation, Chinese policy documents about the New Silk Road, also called ‘One Belt, One Road’, mostly testify to a strong ambition to unlock foreign markets and support domestic firms in taking on foreign competitors. This confirms China’s shift from defensive mercantilism, which aims to protect the home market, towards offensive mercantilism, which seeks to gain market shares abroad. In a context of global economic stagnation, this comes as a major challenge to Europe. As China’s market share grows spectacularly in countries along the New Silk Road, key European member states have both lost market shares and even seen their exports shrink in absolute terms.

Consequences for Europe

If the New Silk Road has one important new ambition, then it is the desire to integrate all China’s previous trade initiatives in order to make its trade policy more efficient and prevent different actors from undermining each other when they go abroad. The New Silk Road confirms China’s focus on access to raw materials and on exports. Given the weakness of its domestic demand, it wants to continue to export labour-intensive manufactured goods, but it now also wants to expand its market share in high-end manufactured goods and different services. The foreign exchange reserves resulting from China’s trade surplus need to be invested in a way that gives China more influence on the international market. The papers relating to the New Silk Road also reveal that the government anticipates that if its domestic economy becomes stronger, consumer demand picks up and companies become more competitive, it wants an orderly outsourcing of manufacturing activities. Labour-intensive factories must be replaced by capital-intensive high-tech producers and the labour-intensive manufacturing that is relocated to other countries must become part of Chinese production chains. In other words, China wants to have a Chinese alternative to today’s multinationals. The New Silk Road, finally, shows that the Chinese government wants to set the terms of trade and determine technical standards to the benefit of its companies.

This all adds up to a very ambitious offensive mercantilist strategy. China understands that its economy remains vulnerable, but it is confident that it can manage this, not by closing its door to the international market, but by manipulating openness. China’s offensive mercantilism is about promoting free trade, while national companies still benefit from staggering amounts of credit and different forms of trade support. It is about making partner countries more connected to the Chinese economy than to competing economies, like the United States, the European Union and Japan. Such competitive connectivity involves new networks of communication, transportation, but also harmonisation of rules and standards. China’s offensive mercantilism seeks to promote a form of economic harmony that is in fact an economic hierarchy. While partner countries can gain from exporting raw materials, tourist services and, in the longer-term, labour-intensive goods, China wants to dominate new strategic industries with high value-added.

This strategy is a tremendous challenge for Europe. China’s new push for trade comes at a moment when economic growth along the New Silk Road is stalled. Between 2008 and 2014, the imports of European goods and services of countries along the New Silk Road only grew by two percent annually, compared to 19 percent annual growth between 2000 and 2008. Between 2008 and 2014, Europe’s exports to Silk Road countries decreased by USD 25 billion, whereas China’s exports grew by USD 250 billion. So, even in absolute terms, Europe lost significantly. In relative terms, Europe’s market share decreased from 38 to 30 percent; while China’s market share increased from 9 to 16 percent. Disaggregating this trade, Europe’s loss of market share was the most dramatic in high-tech goods. In this sector, its market share dropped from 62 to 30 percent, whereas China’s market share increased from 15 to 26 percent. All major EU member states have suffered from this evolution. Between 2008 and 2014, France, Germany and Italy saw their exports to Silk Road countries decrease in absolute terms, -12, -6 and -9 percent respectively. All five countries also saw their market shares decrease.

For trade in services, it is impossible to calculate precise patterns, as comparable data are not available. China consistently reports contracted projects, mostly in construction, engineering, power and telecommunications. The European Union reports exports of services, which is a much broader category, and detailed service exports for a select number of countries. Between 2008 and 2014, China’s turnover of contracted projects along the New Silk Road almost doubled from USD 30 billion to USD 57 billion. For the countries with detailed figures available, China appears to have gained a larger market share. For trade in both goods and services, these losses were incurred in only the first three years after the launching of the New Silk Road. In other words, this is just the beginning. If the New Silk Road proves successful, trade losses will become far larger.

Besides the commercial losses, the New Silk Road also undermines Europe’s political influence. If the internal weakening of the European Union has already damaged Europe’s position, China’s economic charm offensive will complicate the situation even more. As the New Silk Road destroys Europe’s external market, it decreases the prospects for recovery in the eurozone. If some relatively weak members of the eurozone are hoping that their export competitiveness can be increased by social and fiscal sacrifices, China’s offensive mercantilism, its generous use of credit and massive export support make that less likely. The failure of these countries to expand their exports could exacerbate tensions between the members of the eurozone, making it more difficult for centre parties to resist Euroscepticism, and thus indirectly contributing to the further fragmentation of the European Union.

Internal cohesion is also weakening because China actively exploits the divisions between the member states and the short-sightedness of their leaders. This is taking place in different ways. First, China mollifies member states’ leaders by buying government bonds. Apart from Germany, this has usually been in small quantities. Externalising public debt relieves some of the economic difficulties in the short term, but it is no solution in the long-run. Second, China presents its exports of cheap goods and services as an opportunity for the leaders of member states to prop up the purchasing power of their citizens. This is, again, true in the short term, but in the longer run, artificially cheap imports damage European companies and, hence, diminish the prospects for sustainable recovery. Third, China uses the New Silk Road to curry favour with domestic interest groups in member states, like port companies, retailers, financial institutions and transportation firms. Those sectors, as a result, lobby for good relations with China and against a tougher trade policy. Yet, however large these sectors might be, they are hardly helpful in reducing the current account deficit of their country and building a competitive industrial base. All these temptations distract government leaders from the one and only important measure of a favourable economic partnership, that is, balanced trade on the current account.

Please click to read the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Guangxi has a 1,020km border, with three prefecture-level cities adjoining Vietnam. Its border region is one of the four areas for development under the strategy of the “four alongs” currently being implemented in Guangxi. Apart from border trade, which plays an important role in the autonomous region, Guangxi is also promoting cross-border economic co-operation to open up and develop the areas along the border. Border platforms such as cross-border economic co-operation zones and key experimental zones for development and opening up will gradually become the important carriers for opening up and co-operation between Guangxi and ASEAN countries. Moreover, Guangxi plans to develop border processing industries in the ports along the border and promote the transformation of border trade from “cross-border transit” to “inbound processing” while strengthening its trade distribution functions.

Important Role of Border Trade

ASEAN is the principal trading partner of Guangxi, topping its trading partner list for 16 years in a row. In 2016, Guangxi’s import and export value with the ASEAN region accounted for 65% of its provincial total. Guangxi’s trade with Vietnam across its border made up 60% of its total trade value in 2016. Commodities in its export list mainly comprise electrical and mechanical products, textiles, garments, agricultural products, ceramic products, vegetables and footwear, whereas its import list covers agricultural products, electrical and mechanical products, fruits, grains, feeds and coal.

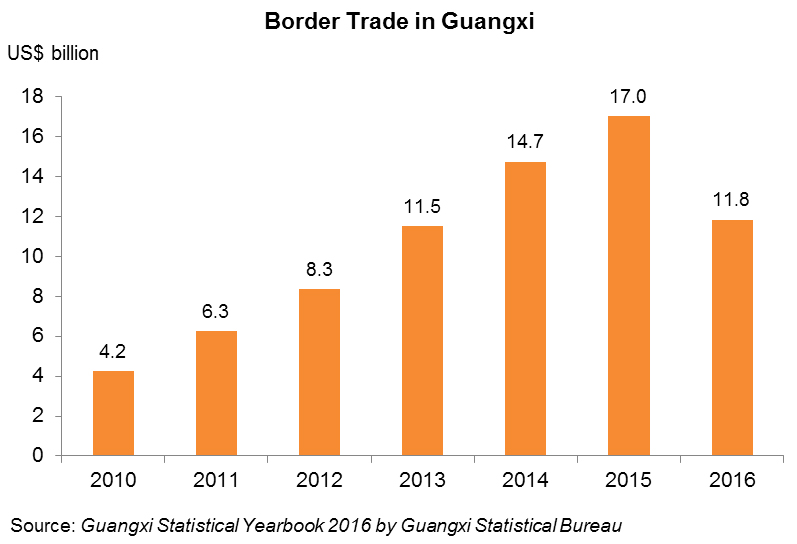

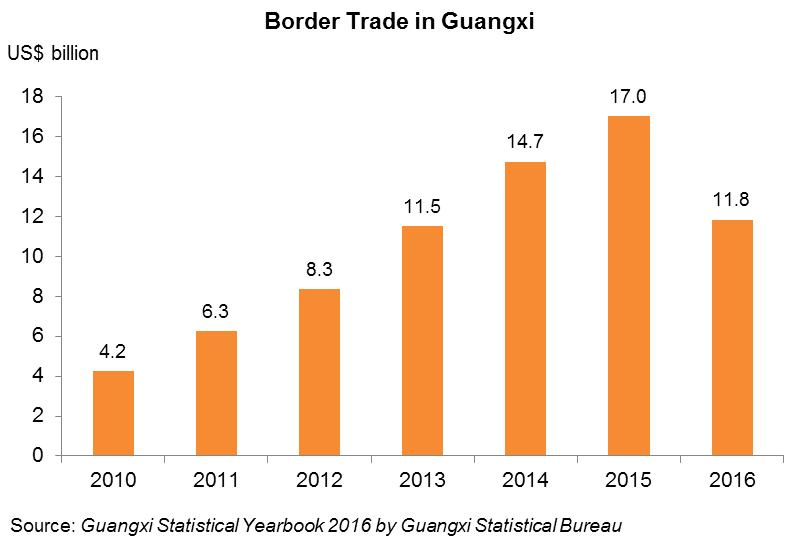

There are 12 border ports and 26 border trading posts in Guangxi. Border trade [1] has been thriving in the autonomous region, constituting 34% of its total trade value in 2014, although the figure dropped to 25% in 2016. These trading activities are mainly conducted with Vietnam, accounting for more than 50% of the total trade value between Guangxi and Vietnam. In respect of Guangxi, more than 90% of its total border trade value comes from exports.

The total border trade value of Guangxi ranks first among all border provinces and regions in China. Export items of its border trade are dominated by electrical and mechanical products and textiles, such as motorcycles, auto parts, small hardware as well as men’s and women’s tops, which constitute some 70% of the total export value of its border trade. Import items mainly consist of agricultural products and mineral products, such as anthracite and minerals of titanium, iron, zinc and aluminium, tropical fruits, mahogany and wood products, which account for about 80% of the total import value of Guangxi’s border trade.

Of all of China’s border ports, Dongxing Port has the highest volume of cross-border passenger traffic. Many Chinese domestic products are exported to ASEAN countries through these border ports, through which products from Vietnam are imported to China. While the port of Friendship Pass is the distribution centre of mahogany products, Dongxing Port has become a distribution centre for marine product processing, and Shuikou is the principal port for nut imports from Vietnam and ASEAN countries.

Development of Border Trade and Processing Industry

In 2016, the State Council of China published the Opinions on Several Policy Measures in Support of the Development and Opening Up of Key Border Regions, which spells out its support for the development of strategic regions along the borders, including pilot zones for strategic development and opening up, national-level border ports, border cities, border economic co-operation zones and cross-border economic co-operation zones. The document mentions that these border regions are becoming the pioneers of China’s implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative. Guangxi has, in fact, started to push forward some border development policies in recent years prior to the publication of the above document.

According to the Memorandum of Understanding on Development of Cross-Border Co-operation Zones signed between China and Vietnam in 2013, there will be three China-Vietnam cross-border co-operation zones in the first batch of development projects, one at the China-Vietnam border of Hekou-Lao Cai in Yunnan province, and two at the China-Vietnam border of Dongxing-Mong Cai and Pingxiang-Dong Dang, both in Guangxi. For the Joint Master Plan on China-Vietnam Cross-Border Economic Co-operation Zones, China has already submitted its draft to Vietnam whereas Vietnam has devised its own draft. Working in collaboration, they will study both drafts and finalise a joint master plan.

Focusing on the development of its border economic belt, Guangxi strives to promote industrial co-operation along the border as well as cross-border interconnection and intercommunication. Border platforms such as economic co-operation zones and national pilot zones for strategic development and opening up will gradually become important carriers for opening up and co-operation between Guangxi and ASEAN countries.

At present, Guangxi is developing the processing industry in border ports while promoting the transformation of border trade from “cross-border transit” to “inbound processing”. It also strives to speed up the development of the cross-border economic co-operation zones of Dongxing-Mong Cai and Pingxiang-Dong Dang along the China-Vietnam border. Permission has been given for border regions such as Dongxing and Pingxiang to expand their pilot zones for cross-border labour co-operation so that its border processing industry can capitalise on Vietnam’s labour force.

Border trade has become the principal form of China-ASEAN commodity trade conducted by small- and medium-sized companies of Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar and Thailand. While some products imported from Vietnam come from other regions, suppliers from other mainland provinces and regions are also attracted to export their products to Vietnam or re-export to other ASEAN countries through the border trade in Guangxi. It is estimated that 80% of Guangxi’s border import trade involves re-sales to other mainland regions. In view of this, apart from promoting a border processing industry, Guangxi plans to build up a more extensive market distribution function. For example, Pingxiang is planning to expand its specialised fruit distribution market.

Pilot Zones for Development and Opening Up Boost Growth of Border Regions

Upon the approval of the State Council, two key pilot zones for development and opening up have been set up along the border in Guangxi – the Dongxing Key Pilot Zone for Development and Opening Up officially established in 2014, and the Pingxiang Key Pilot Zone for Development and Opening Up approved in August 2016.

The Pingxiang Key Pilot Zone for Development and Opening Up has a planned area of 2,028 sq km with Pingxiang City as its core supported by six major functional zones, namely, an international economic, trade and commercial zone; an investment co-operation development zone; a key border economic zone; a cultural and tourism co-operation zone; a modern agricultural co-operation zone; and a border city pioneer development zone.

The Dongxing Key Pilot Zone for Development and Opening Up covers Dongxing City and the port district with a total area of 1,226 sq km. Dongxing City, under the administration of Fangchenggang Municipality, is just across the river from Mong Cai City in Vietnam. The daily passenger traffic of Dongxing port is about 20,000 to 30,000, and its annual total reached 7.15 million in 2016.

Capitalising on the platforms of the Dongxing Key Pilot Zone for Development and Opening Up, the Dongxing China-Vietnam Cross-Border Economic Co-operation Zone inside the Key Pilot Zone, as well as the Financial Reform Pilot Zone along the border, Dongxing is poised to develop six major cross-border industries. The six are: cross-border trade, cross-border tourism, cross-border processing, cross-border e-commerce, cross-border finance and cross-border logistics, all aim at serving Vietnam. Specifically, cross-border trade will focus on mutual trading activities between border residents of both countries; cross-border processing will concentrate on marine products and agricultural by-products, as well as the deep processing of mahogany (four mahogany markets have already been set up in Dongxing) to form distribution centres of related products; and cross-border e-commerce aims to promote the integrated development of border trade and e-commerce, particularly in respect of agricultural by-products.

The Dongxing Key Pilot Zone for Development and Opening Up is mainly characterised by its policy of introducing “early and pilot” measures. The Pilot Zone can explore different policy innovations, including the forms of opening-up and co-operation, as well as financial and tax management models. All innovative policies of opening up, co-operation and reform, such as those on customs facilitation, China-Vietnam integrated border control, and cross-border labour administration, are possible areas for exploration by the Pilot Zone.

One of the major tasks of the Dongxing Key Pilot Zone for Development and Opening Up is to develop a cross-border economic co-operation zone at the China-Vietnam border of Dongxing on both sides of the Beilun River. A core zone of 10 sq km has been planned for Dongxing on the China side, whereas the park zone on the Vietnam side covers 13.5 sq km, with a bridge connecting both sides. The co-operation zone will be operated in the forms of “shop in front and factory at the rear”, “two countries, one zone”, “within and beyond the border”, and “closed border operation”. Planned to “open at the first line and control at the second line”, the zone will pursue the closed operation model of a cross-border free-trade zone within which people, goods and vehicles of both sides can flow freely.

Infrastructural facilities on the Chinese side of the co-operation zone are basically complete, as is the bridge to link the two sides of the zone. The official commencement date of closed operation of the zone has yet to be finalised. The Chinese part of the zone will be developed into three districts. The first is a financial, commercial, trading and tourism district covering 2.06 sq km. The second, with an area of five sq km, is a garment and agricultural by-product industrial district for processing trade, and the third is a logistics and warehouse district. Construction of the first district has been topped out to provide, inter alia, an ASEAN attractions street, and is expected to open to all visitors with identification documents. The daily duty-free limit is RMB8,000 per visitor.

Nine standard factory blocks with a total floor area of more than 60,000 sq m will be completed in the processing trade district by the second half of 2017. Two standard factory blocks have already been constructed, and a mobile-phone assembly plant has moved in for operation. Its finished products are to be exported to Vietnam, while those processed with raw materials from Vietnam will be sold to the Chinese mainland. As the zone will make use of the Vietnamese workforce, the next step is to regulate and quantify the cross-border use of workers with the establishment of a labour management centre.

On the Vietnam side, it is understood that the planning and design blueprint has been completed. In the Dongxing area, there will be a core zone and a number of supporting zones such as an industrial park, a logistics park and a border trade centre. Inside the Jiangping Industrial Park, there are already more than 100 enterprises operating.

With the current direction of development, the cross-border economic co-operation zone and supporting zones can enhance Dongxing’s commercial and trade functions, including commercial services for external trade, commodity exhibition and sale, warehousing, transportation and tourism, helping to shape the city as China’s comprehensive trade centre targeted at Vietnam and entrusted with the integrated functions of processing production, purchasing and transit transportation. Hong Kong companies interested in capitalising on the border policies of China to capture ASEAN market opportunities should take note of the development of these commercial and trade functions.

[1] Border trade refers to the import and export trading activities conducted at designated land border ports between enterprises registered in Guangxi and approved by the government departments of foreign trade and economic co-operation/commerce with border trade operator qualification, and the enterprises or other trade organisations of neighbouring countries of Guangxi or countries adjoining its border.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Deborah Weinswig, Fung Global Retail & Technology

Introduction

Led by China, the One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative involves massive infrastructure investment in Eurasia and Africa. This is expected to improve connectivity and the business climate in those regions. The US is not one of the 65 countries included in the OBOR. However, we believe US companies will also benefit from better connectivity in the long-term because emerging markets will be further developed.

This report looks at how Western multinational companies can capitalize on these emerging opportunities, with a focus on consumer-goods companies. First, we outline the details of OBOR, including its funding and its position in the landscape of global cooperation and integration.

OBOR Implications

Improved Connectivity Translates to More Business Opportunities for Western Multinational Companies

We believe there is much scope for multinationals to capitalize on increased connectivity in the OBOR regions. Improved infrastructure investments and connectivity may open new markets for US and multinational companies and ultimately drive US economic growth. The US currently has close trade ties with countries along the OBOR and we believe they stand to benefit from improved connectivity and business climate in the region.

The US economy is, in part, dependent on the ability of US firms to compete successfully in overseas markets. More than 95% of the world's consumers live outside the US, and approximately 18% of US manufactured exports are sent by American parent companies to their foreign affiliates, according to the US Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs.

For Western companies, the OBOR initiative means new business opportunities in the ASEAN, Central Asia and African countries. In particular, ASEAN—a $2.5 trillion economy that is the world’s seventh-largest and Asia’s third-largest, just behind China and Japan—is poised for strong growth on the back of a young workforce, improving infrastructure and rising incomes.

Any economic impact from the OBOR initiative, however, will likely be felt in the longer-term because infrastructure projects in the underdeveloped regions along the OBOR will take years to complete.

- We see the following benefits to businesses, including Western companies, from the OBOR initiative: Improved infrastructure conditions along the OBOR countries will likely be positive for Western multinational companies in their continuous drive to optimize manufacturing costs: not only will it probably result in lower transit costs, but the infrastructure will enable companies to tap into the lower wages of emerging economies along the OBOR. Although Western multinational companies already have manufacturing bases in many of these countries, higher connectivity will likely reinforce this trend going forward. As a result, Western consumers stand to benefit from lower prices when lower costs are passed through to end users.

- Improvements in the business climate and in disposable income along the OBOR will also likely drive demand for consumer goods and food and beverage (F&B) categories, in turn benefitting multinational companies. Multinational companies and brands will further gain from enlarged catchment areas for their products due to improvements in infrastructure and the removal of non-tariff barriers that will make it easier for them to carry out business.

- Finally, sectors as diverse as trading, tourism, logistics, energy and infrastructure in countries along the OBOR are poised to benefit from upgrades in infrastructure, utilities, energy and related industries. We discuss the possible impacts on a logistics firm, DHL Express, and the tourism industry later in this report, and we provide a case study of Kerry Logistics directly below ...

Key Advantages: IP and Brands

We see IP and brand equity as major advantages for Western companies:

- IP: Advanced and innovative technology is one of the biggest advantages held by Western multinational companies when they expand into emerging markets. However, IP protection in these markets is still relatively weak and regulatory systems need further improvement. India ranked the second lowest in IP protection regulations, according to the US Chamber of Commerce International Intellectual Property Index of 2016. The gradual improvement of the regulatory environment will raise awareness and offer more IP protection for multinationals.

- Established brands: Multinational companies can harness the power of their brands to capture the loyalty of emerging market customers. Tapping into emerging markets that are characterized by structural increases in disposable income and a rising middle class will be an important part of the global strategies of multinational companies.

Key Challenge: Competition from Local and Regional Players

Multinational companies, with their established franchises, have enjoyed competitive advantages as they expand into emerging markets. The gap may close in the future, however, as Chinese companies intensify their overseas expansion. We outline some of the key challenges for international retailers below:

- Local competition: We see local competition as the main challenge for global brands. Local players are better attuned to the tastes of local customers than their international counterparts. They are likely to have low cost structures, better access to regulators and are also positioned to benefit from OBOR. For example, Carrefour, a French hypermarket experienced difficulty keeping up with the shopping habits of the Chinese customers after it entered China in the 1990s. The habit of Chinese customers is to shop daily for fresh food and they treated hypermarkets as convenience stores instead of buying in bulk as many Western shoppers do.

- Regulatory risk: In addition, the regulations of many markets along OBOR may have opaque decision-making process and incentives, which may prove challenging for international companies to adapt to.

- Credit risk: International companies have developed credit and payment systems that protect them against counterparty and default risk. In overseas markets, international companies will face customers that may operate on different credit, payment and enforcement principles.

- Supply chain risk: Supply chain risks stems from firms operating in emerging markets which may have limited visibility of suppliers and distributors and may lead to delivery delays and quality control issues. In some cases, we expect multinationals will cooperate with local or regional players as a means of mitigating local risk, especially in areas that prove too costly for the multinational companies’ expansion. DHL’s cooperation with local postal agencies in remote areas in ASEAN is a good example.

Please click to read the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

The lower labour costs, improved infrastructure and preferential tax treatment have all led to Vietnam attracting a significant inflow of foreign direct investment (FDI). Increasingly, the country is now targetting investment from higher value-added industries, with potential investors advised to look beyond labour cost advantages. There are, however, genuine concerns as to the lack of engineering expertise and ancillary industries within the country, a particular challenge for any business undertaking more sophisticated production with higher degree of automation.

In order to tackle this shortfall, certain investors – including a number from Hong Kong, are making use of the technical and other services, as well as material supplies from the Chinese mainland as a means of supporting their Vietnamese operations. Even for the infrastructural development, such as those in Northern Vietnam bordering China, one of Vietnam’s development directions is to strengthen the country’s access to the Chinese supply chain. In the circumstances, effective management and efficient logistics services are crucial when it comes to ensuring foreign investors and other related companies can properly orchestrate their cross-border arrangements and achieve the maximum operational efficiency.

Enhancing the Infrastructure of Northern Vietnam

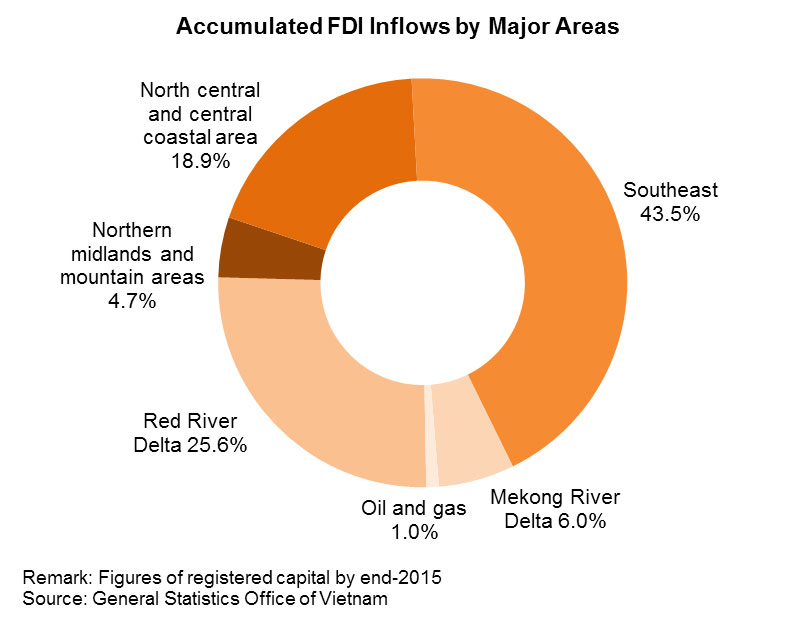

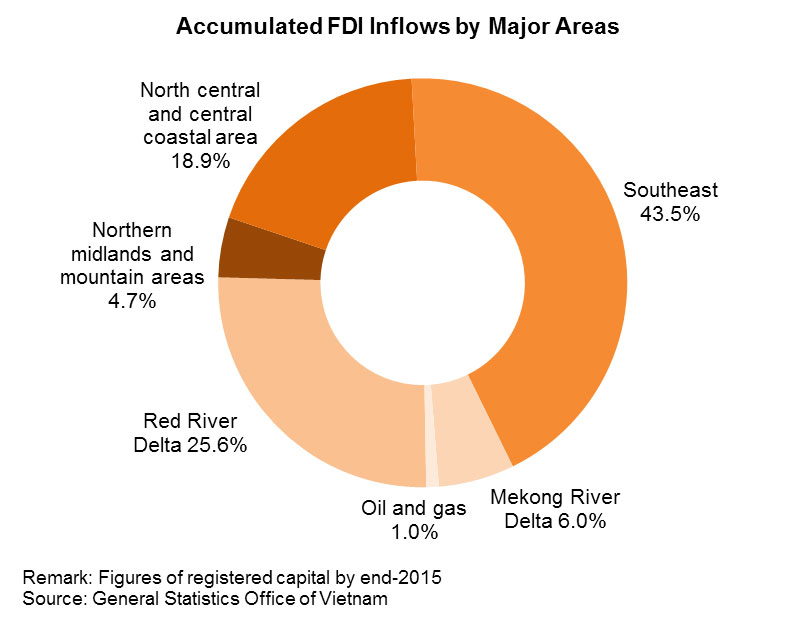

Northern Vietnam is being increasingly targetted by foreign investors, many of whom had previously favoured business opportunities in the south of the county. Highlighting this traditional preference, at the end of 2015, the southeast part of the country – extending across Ho Chi Minh City, Dong Nai and Ba Ria-Vung Tau – accounted for 43.5% of the total accumulated FDI inflow. By comparison, the Red River Delta – including Hanoi, Bac Ninh and Hai Phong – accounted for just 25.6% of the cumulative total. More recently, nonetheless, the northern cities and provinces have started to attract a greater proportion of overall FDI. This is down to both a greater effort on the part of the government to promote the economy of the north and a marked improvement to the infrastructure across the region.

A sign of this change in emphasis is the city of Hai Phong, which attracted the second highest level of FDI in Vietnam in 2016, solely trailing Ho Chi Minh City. Hai Phong is set within the Hanoi-Hai Phong-Ha Long economic triangle. It is also the site of Northern Vietnam’s largest seaport. Of late, sea freight connections between Hai Phong and the ASEAN, US and European markets have been bolstered by the increased availability of container liner services, the consequence of a shift in focus by the international shipping companies.

Cat Bi International Airport, Hai Phong’s principal air transportation hub, has direct links to several other Vietnamese regions, including Ho Chi Minh and Da Nang, as well as offering flights to other Asian countries. The completion of a new highway connecting the city to Hanoi, the country’s capital, has also provided a boost to business and industrial activities in the Hai Phong region. The highway also extends to Ha Long, capital city of the resource-rich Quảng Ninh province. Additionally, Hai Phong’s access to the markets and supply chains of southwest China have been further improved by the completion of highway connections to Mong Cai and Lang Son, the two Vietnamese cities that respectively border the Chinese townships of Tongxing and Pingxiang of Guangxi region.

Hai Phong: The Cost Benefits

Overall, the improvements to its infrastructure have made Hai Phong far more attractive to a range of business and industrial investors, with the success of the VSIP Hai Phong Industrial Park being an example of this. Jointly established in 2008 by a Singapore consortium and a Vietnamese state-owned enterprise, it has a total area of 1,600 hectares, of which 500 hectares are reserved for industrial development. The remaining space has been given over to a range of commercial and residential projects.

As well as benefitting from improvements to the local transportation network, VSIP Hai Phong also owes much to its success to its access to all the required utilities, including reliable electricity, water supplies and optical fibre telecommunication services. This has seen it attract projects largely related to higher value-added industries. To date, these include companies specialising in:

- Electrical and electronics

- Precision engineering

- Pharmaceuticals and healthcare

- Supporting industries

- Consumer goods

- Building and specialty materials

- Logistics and warehousing

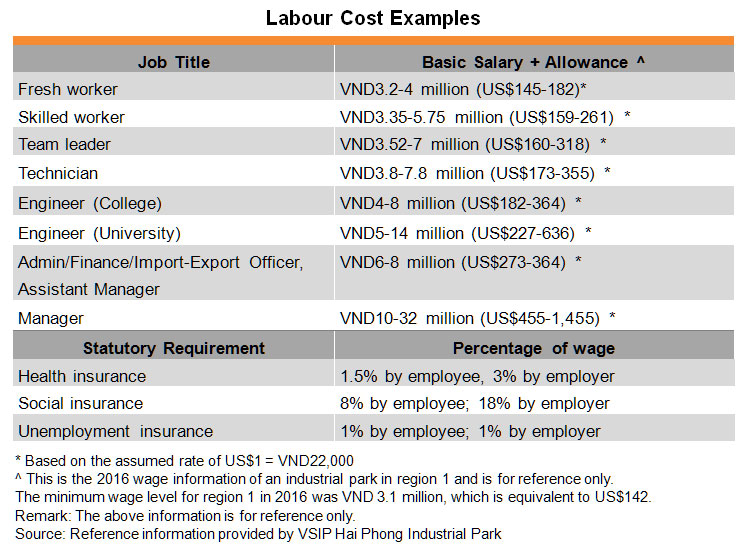

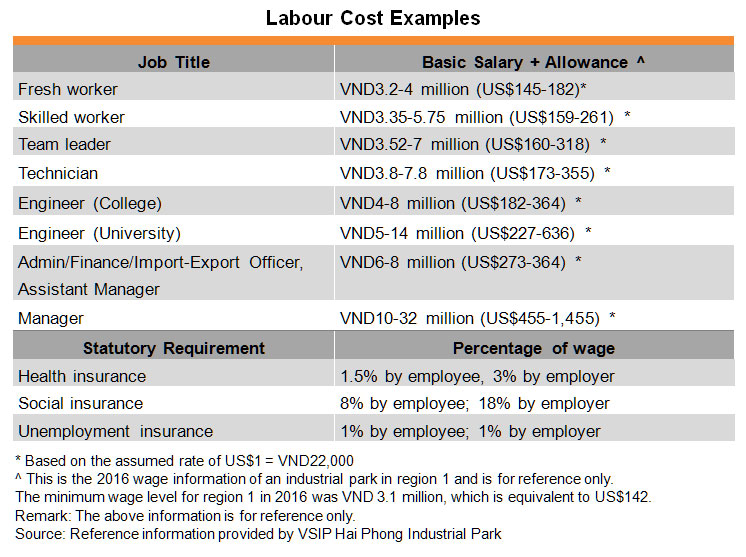

In line with the latest government regulations, industrial investors in VSIP Hai Phong are entitled to claim a range of tax benefits, including preferential corporate income tax rates and exemption from certain import taxes (those related to export processing enterprises[1]). Employees working in the park also pay a lower level of personal import tax[2]. In addition to this, labour costs are relatively low in Hai Phong and its neighbouring regions, with the total monthly cost per worker – factoring in statutory contributions, such as insurance – starting at around US$200-250. This is a relatively low cost when compared to the current wage levels in China.

(Remark: For more information regarding labour costs, please see: Vietnam’s Youthful Labour Force in Need of Production Services.)

Seeking Production Supports from China

According to VSIP Hai Phong, the park is currently home to some 35 industrial projects, with investments sourced from ASEAN, Japan, Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong. An estimated 70% of its industrial areas have already been occupied by such projects. For the future, the park plans to attract more high-end investments, specifically those related to production of technology products and the supporting industries. Any such investments, of course, will be obliged to comply with all the statutory environmental regulations, although any potentially polluting industry that demonstrates it can meet the required emission standards may not be refused.

Many of the industrial projects based in the park are related to processing production, particularly with regard to textiles and clothing items, electronic products and packaging materials. Among the other investors are several companies engaged in the manufacture of intermediate goods, the majority of which are utilised as production inputs by downstream clients in Hai Phong and Northern Vietnam. Production of this kind, however, relies heavily on imported industrial goods and raw materials. One foreign-invested company, which undertakes the assembly production of electronic products and office machinery, for instance, has indicated that it is sourcing competitively-priced, high quality parts and components from elsewhere in Asia in order to support its Hai Phong production activities.

Several Hong Kong-invested companies are also operating in VSIP Hai Phong. One of them, which has a focus on plastic injection moulding, metal stamping and die-casting, told HKTDC Research that it had established a manufacturing operation in Vietnam in order to follow in the footsteps of one its downstream clients. Typically, the plastic and metal outputs of its Hai Phong factory are mainly used for the processing production of IT and other electronic products by its clients in Vietnam. As such, maintaining the Hai Phong factory saves the company money when it comes to logistics costs, while shortening the delivery lead time to its downstream clients. As another plus point, it also enjoys the accrued tax benefits of being based in Vietnam.

While acknowledging a number of clear advantages of being based in Vietnam, maintaining an operation in Hai Phong has not been without its challenges for the company. One of its particular problems is related to the relatively low skill levels of many local workers, with their productivity, consequently, a bit lower than that of their counterparts in southern China. While Vietnamese labour costs are lower, in productivity terms, the labour cost differential between Vietnam and China is far from substantial. In order to enhance its production efficiency, the company is now planning to further automate its operations, a development that will see it requiring lower staff levels. Labour costs, therefore, will ultimately become relatively insignificant when it comes to considering further investments at the site.