Chinese Mainland

By Vice-Admiral Patrick HÉBRARD, Associate researcher, Fondation pour la recherche stratégique, FRS, Paris

(This study was commissioned by the European Parliament's Sub-Committee on Security and Defence)

Abstract

China’s New Maritime Silk Road policy poses geostrategic challenges and offers some opportunities for the US and its allies in Asia-Pacific. To offset China’s westward focus, the US seeks to create a global alliance strategy with the aim to maintain a balance of power in Eurasia, to avoid a strong Russia-China or China-EU partnership fostered on economic cooperation. For the EU, the ‘One Belt, One Road’ (OBOR) initiative by improving infrastructure may contribute to economic development in neighbouring countries and in Africa but present also risks in terms of unfair economic competition and increased Chinese domination. Furthermore, China’s behaviour in the South China Sea and rebuff of the ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, in July 2016, put the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) at risk with possible consequences to freedom of the seas. Increasing relations with China could also affect EU-US relations at a time of China-US tension. To face these challenges, a stronger EU, taking more responsibility in Defence and Security, including inside NATO, is needed.

Introduction

On 7 September 2013, President Xi Jinping proposed the building of the ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ during his visit to Kazakhstan. The same year, on 3 October, addressing the Indonesian parliament, he proposed the building of a ‘New Maritime Silk Road’. Both are now collectively called ‘One Belt One Road’ (OBOR) initiative. At the Boao Forum on 28 March 2015, China released the ‘Vision and Action on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road’ indicating that the OBOR initiative has officially become one of China’s national strategies. According to the Chinese authorities, One Belt refers to the land-based Silk Road, whereas One Road refers to the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road.

At the end of 2014, China set up the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in October and the Silk Road Fund (SRF) in November to sponsor Asian connectivity and development programmes. They function together as complementary wings of Asian development.

China’s OBOR initiative has provoked both positive and negative comments and interpretations internationally. Some observers view it as a grand strategy for extending China’s economic and geopolitical influence into ASEAN, Eurasia and beyond, while others are concerned that OBOR might reshape global economic governance and lead to the rebirth of China’s domination in Asia.

Furthermore, Chinese and foreign media quickly described OBOR as the ‘Chinese version of the Marshall Plan’, and the BRICS Bank, the AIIB, and the Silk Road Fund as key components of that plan. The Belt and Road project is undoubtedly the most important international project that China has embarked on in the last few decades. It aims to stimulate economic development over a vast area covering sub-regions in Asia, Europe and Africa.

Although there has been no official announcement about what countries are covered by the Belt and Road initiative, some official sources point to the involvement of at least 63 countries, including 18 European countries. Particularly relevant for Europe is that the Silk Road ends where the European Union (EU) starts. This massive bloc between the EU and China accounts for 64% of the world’s population and 30% of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

This study will focus on the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. In a first part, it analyses the challenges to the freedom of the seas in Asia, giving particular attention to China’s maritime interest sphere. The second part analyses the role of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’, in this context, while the third part is devoted to the United States and its allies’ role in the security policies in the region. From the above, the fourth part describes the effects of the strategic choices made by regional powers and the United States on European Union cooperation, foreign and security policy deployment in the region, noting possible implications on Euro-Atlantic cooperation. The fifth part describes and analyses the legal dimension of disputes in the context of UNCLOS and of the ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the case of the South China Sea. In the last part, the study proposes some policy options for the EU.

- Current challenges to the freedom of the seas in Asia

- The role of the ‘One Belt One Road’ initiative

- The role of the USA and its allies in the security policies in the region

- Effects on the European Union’s policy in Asia Pacific and on Euro-Atlantic cooperation

- Consequences of the ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the case of the South China Sea

Policy options for the EU

China’s OBOR initiative affords both opportunities and risks due to China’s behaviour in the China’s Seas and hidden strategic policy. For the United States, China’s increasing grip on the South and Central Asia is certainly unacceptable, and US President elect Trump’s telephone call to the Taiwanese President seems to show the future way of the US strategy in the area.

The magnitude of OBOR’s impact on the EU's long-term geopolitical, economic and geostrategic interests will also depend on whether the EU responds to OBOR with one voice and coordinated policies.

Relying on a soft power approach with a focus on international law, the EU is not seen as a strong security player, which leaves it with some possibilities to initiate a maritime security governance mechanism and framework that can mitigate the risk of the Asia-Pacific area being affected by Great Power tensions. This should be done, obviously, in close cooperation and coordination with regional countries.

In accordance with the above the policy options for the EU could be the following:

- In her foreword to the European Union Global Strategy, the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Vice-President of the European Commission states rightly: The purpose, even existence, of our Union is being questioned. Yet, our citizens and the world need a strong European Union like never before… None of our countries has the strength nor the resources to address these threats and seize the opportunities of our time alone. But as a Union of almost half a billion citizens, our potential is unparalleled… We will deliver on our citizens’ needs and make our partnerships work only if we act together, united… Yes, our interests are indeed common European interests: the only way to serve them is by common means. This is why we have a collective responsibility to make our Union a stronger Union. A fragile world calls for a more confident and responsible European Union, it calls for an outward-and forward-looking European foreign and security policy.’65 Consequently, the first action will be to build a ‘credible Union’, anchored on its shared values if the EU wants to be able to discuss as equals with the Great powers.

- EU policy has always promoted international law (UNCLOS) as the basis for maritime governance and cannot accept China’s rebuff of the ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration. That said, the EU must act to avoid a confrontation between China and the USA in the South China Sea, which would have an immediate impact on maritime traffic and world trade. The development of a code of conduct in the South China Sea should be actively pursued and bilateral and multilateral discussions must be encouraged to find an agreement on EEZ delimitations, on fishing and environmental rules and on freedom of navigation in the area, in accordance with the UNCLOS and taking into account the security of China’s strategic nuclear deterrence. Proposing the EU Integrated Maritime Policy (IMP) as a basis for discussion could be helpful.

- The EU policy towards ASEAN is competing with China’s OBOR project. For ASEAN these increasing ties with other countries are welcomed as they contribute to economic growth in the region and offer the possibility not to be excessively dependent on its main partner, China, in coherence with ASEAN concept of centrality. As analysed by the High Representative, the EU should intensify its relations with ASEAN, increasing its presence and facilitating progress in ASEAN confidence-building measures.

- The evolution of China’s strategy and the situation in the East and South China Sea require constant monitoring. This calls for intelligence gathering by European intelligence agencies for improved awareness and decision-making.

- The EU’s interests do not always coincide with those of the United States, and the EU benefits from taking a more independent position on security issues related to Asia. The EU member states must also consider that relations with the US have changed and will continue to evolve. For the USA, the EU is an economic power and a competitor on the world markets. The euro is seen as challenging the dollar’s supremacy and the US strategic priorities have shifted to Asia and the Middle East, as shown by the rebalance of the US military forces66 to these areas. President elect Trump has announced he will give less support and take some distance from its European allies. The EU must strengthen defence and security ties among member states, increase defence efforts and assume a greater role within an ‘obsolete’ NATO.

- The US rebalance towards Asia requires Europe to take a greater responsibility for stability in its immediate surroundings, especially in the Mediterranean, in the western Indian Ocean and in Africa. All observers agree to say that operation ATALANTA in the Horn of Africa, is a success. In spite of the difficulty of its mission, operation SOPHIA is saving migrant lives and helps Libya to rebuild its Navy and Coast Guard. A permanent activation of EUROMARFOR, with a European Maritime Force, sailing in the Mediterranean or alongside the West African coasts would offer the necessary means for presence and surveillance at sea, training with foreign navies and crisis prevention, in relation with NATO.

- Maritime domain awareness is a prerequisite to maritime security. While the US is developing the MISE (Maritime Information Sharing Environment) and the EU, the CISE, (Common Information Sharing Environment), the South East Asian countries have established the IFC (Information Fusion Centre) in Singapore and India is developing its own system. Connection between the different networks will improve considerably the maritime surveillance and awareness. Furthermore, the EU’s PMAR-MASE67 programme for Eastern and Southern Africa and Indian Ocean is financing a maritime regional IFC in Madagascar with the aim to connect it to Singapore’s IFC.

- OBOR opens opportunities for the EU to pursue its geostrategic ambitions68 in Central Asia by deepening the EU-China strategic partnership through cooperation in non-traditional security fields, as decided in 2007 and confirmed in 2015. This could possibly pave the way to EU-Russia reconciliation. It may be advantageous for the EU to consider how its existing policy tools and strategies, such as the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) and the EU Maritime Security Strategy, could be linked with OBOR and how this strategic alignment could feed into the EU's Global Strategy for Foreign and Security Policy.

- China’s new initiatives will accelerate the growth of its influence in the maritime domain as well as in Asia, Africa and Europe more broadly. An EU proactive approach to closely working with local actors and coordinating actions or programs with China when it is of added value, seems to be the best way to preserve European interests and role. For example, the EU has a real interest in supporting the 2050 Africa’s Integrated Maritime Strategy (2050 AIMS) to improve security, tackle IUU and piracy and develop Africa’s economies, and coordinating with Chinese investments in ports and infrastructures.

Please click to read full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

The Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway is the latest beneficiary of China's African investment programme, with the BRI set to ensure that the number of such projects is set to increase, but are China and Africa's agendas truly compatible?

Djibouti is among the tiniest of all of the African nations, while Ethiopia has long been considered the economic powerhouse of the Horn region of East Africa. Both, however, are clear beneficiaries of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China's massive international infrastructure and trade development programme.

While Djibouti may be diminutive, its port packs a punch, occupying, as it does, a strategic position straddling the entrance to the Red Sea. The country also has a substantial military presence, including the largest American military base in Africa. By contrast, Ethiopia, a nation with the second-largest population on the continent, is a true regional economic bright spot.

These two countries, although markedly different, have now been linked by the Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway, a project largely realised through Chinese engineering and investment. Officially opened in October 2016, Africa's first cross-border electric railway was built by the China Railway Group and the China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation, while most of the US$4 billion financing came from the Exim Bank of China.

The new 750km railway provides a much improved import-export corridor for landlocked Ethiopia. Most significantly, it slashes the seven-day road-freight journey from Addis Ababa to the port of Djibouti to just 10 hours. The outcome of a strategic partnership between China and Africa, the rail link is viewed as an integral part of the BRI.

More recently, in June this year, another China-funded/managed project, the Mombasa-Nairobi Line, went into operation. The 485km line is actually phase I of a much bigger project – a $14 billion standard-gauge railway network that will eventually extend from Kenya on to Uganda then to Rwanda.

Once completed, it is hoped that this network will open up many of the landlocked East African markets to Chinese manufactured goods via the port of Mombasa. It is also anticipated that it will improve the supply chain for African mineral commodity exports, resources that China increasingly relies upon.

The two rail projects are just the latest in a long line of engineering initiatives that have seen China establish a substantial presence in Africa. Back in the 1970s, China built the Tazara Railway, which connected landlocked Zambia and its copperbelt with the Tanzanian port of Dar es Salaam. At the time, this was China's largest aid project in Africa.

More recently, China's commitment to major infrastructure projects across Africa has formed a key element of its BRI agenda. It is also clear that China is keen to play a major role in Africa's economic development, a policy that will only enhance its commercial presence on the continent.

Acknowledging this, during the 2015 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation Xi Jinping, China's President, committed to a generous US$60 billion package of development assistance for Africa. Much of this was earmarked for investment in several major infrastructure projects, including the new Ethiopia-Djibouti Railway and a series of port upgrades along the East African coast.

Assessing China's game plan, David Monyae, a political analyst at Johannesburg University's Confucius Institute, said: "China has enhanced its role on the continent with a no-strings-attached approach to investment and commercial engagement. This has created the impression that Beijing is ready and willing to support Africa's development efforts."

Other analysts, however, have been more cynical, asserting that the BRI is a means for China to create not only a global trading bloc, but also to establish a "zone of influence". One such commentator, Peter Fabricius, a consultant for South Africa's Institute for Security Studies, said: "Xi may be taking advantage of a fortuitous opportunity to extend China's economic and political influence as a world leader. This could see it capitalising on a moment of American global capitulation under Donald Trump, the notoriously isolationist US President."

Fabricius is not alone in seeing a clear indication that a new international economic order may be emerging. As a sign of this, China recently established a military base in Djibouti, alongside those already leased to several other countries, including the US and France.

Others, however, refute that the BRI projects underway across the continent form part of a clandestine power grab. Instead, they maintain that China's investments in East Africa are purely part of a wider trade network, one intended to improve access to Africa's one-billion strong consumer market. As such, it is thought, they should be seen as a development drive that is looking to nurture joint progress through enhanced trading pathways.

Whether the two – geopolitical assertiveness and an increased global trading network – can be genuinely separated out is something of contentious issue. Either way, as one writer – Peter Bruce, one of South Africa's leading business journalists – said: "Chinese influence in Africa is immense, visible and spreading fast."

For many, the key question is whether what works for China will also work for Africa. The African Union, a body that represents all 55 countries across the continent, is optimistic that it will. It has long made it clear that it is keen for China to partner with many of Africa's infrastructure and technology programmes.

Perhaps going some way to explain the Union's enthusiasm, Greg Mills, a South African economist, said: "Chinese contractors and businesses are willing to go to places and work in conditions that few in the West would contemplate."

Made in ChinAfrica

It's not just infrastructure deals, however, that are attracting Chinese investors to Africa. According to the World Bank, an estimated 86 million low-skilled manufacturing jobs are set to be outsourced from China, a consequence of the rising cost pressures caused by higher wage expectations. Ultimately, it is expected that Africa will be the primary beneficiary of this shift in labour demand.

Assessing this likely change, Mills said: "Low-tech, high-labour manufacturing cannot be done virtually and, as China moves up the development scale, Africa can realistically hope to meet this demand."

One sector where such a process is underway is the textile industry, with China having relocated some production facilities to Africa. In particular, China has invested heavily in several large manufacturing projects in Ethiopia, with the East African country set to become the continent's garment manufacturing hub.

Ethiopia is already one of Africa's fastest-growing economies, with the country having pursued a policy of deliberately keeping labour costs low in order to create a competitive advantage. One industrial park, near Addis Ababa, the nation's capital, now houses some 80 Chinese textile firms, all attracted by low or zero tariffs and cheaper labour – comparative industry wages are 15 times lower in Ethiopia than in China. The Huajian Group, a Zhejiang-based footwear manufacturer, has also invested heavily in a large plant in the park, which currently has more than 3,000 employees.

Overall, improved transport infrastructure – much of it funded by China – has led to manufacturing efficiency improving across Africa. Once landlocked Ethiopia, for example, now has direct access to a port following the opening of the Addis-Djibouti Line.

It should be no surprise then that several other African countries, notably Morocco, South Africa, Cameroon and Togo, are now said to be angling for Beijing's attention. Given that Chinese companies have already created some 600,000 jobs across Africa, it is pretty much inevitable that every country on the continent would look to capitalise on the possible spoils of the BRI.

For its part, China clearly believes that outsourcing some of its manufacturing requirements will help make certain African countries more self-sufficient. The naysayers argue, however, that China is taking advantage of cheap labour, demonstrating that it's indifferent to the repressive regimes and poor governance that characterise many of its partner countries across Africa.

Despite these concerns, it's indisputable that Africa needs to create a larger manufacturing sector if its economies are to achieve sustainable growth in a global environment where falling commodity revenues seem a long-term reality. It is also clear that China is looking to capitalise on this need.

Ultimately, as with all other investors, China wants to ensure it is getting a good return on its capital, a policy that is more than apparent in its approach to its African infrastructure projects. Highlighting this, Bruce said: "China does almost no work in Africa from which it does not derive some form of benefit, either political or economic."

As was the case with China several years ago, Africa is now keen to participate more fully in the globalised economy. For many, if the BRI can help boost development across Africa and drive economic activity, then that can only be a positive for the continent.

Mark Ronan, Special Correspondent, Cape Town

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Fung Business Intelligence

With a joint communique signed by the attending government heads and an extensive list of 270 deliverables, the first Belt and Road Forum (BRF) concluded fruitfully in Beijing on 15 May. Featuring the theme ‘Cooperation for Common Prosperity’, the two-day forum drew around 1,500 delegates from more than 130 countries and 70 international organizations, including 29 foreign heads of state and government.

The BRF is touted as China’s highest-profile diplomatic event of the year, and a first-of-its-kind international conference promoting the Belt and Road Initiative, which was proposed by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013 and has involved over 100 countries and international organizations so far. The second BRF will be held in China in 2019, Xi announced at the close of the forum.

Inspired by the ancient silk routes and previously known as ‘One Belt, One Road’, the Belt and Road Initiative is an ambitious plan spearheaded by the Chinese government to promote trade and economic integration across Asia, Europe, Africa and possibly beyond. The Initiative, which includes the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, aims at creating an open platform among the participating countries and international organizations to improve policy coordination, infrastructure connectivity, trade and finance collaboration, and people-to-people bonds.

I. Highlights of President Xi’s Keynote Speech

In his keynote speech delivered at the opening ceremony, President Xi repeated his call for an open world economy and reiterated China’s objective of pursuing the Initiative is to create ‘a new model of win-win cooperation’ but not ‘geopolitical maneuvering’. Besides, he pledged more financial support from China to the Initiative through loans and assistance.

Below are key highlights of President Xi’s keynote speech [1]:

- Renewing the Silk Road spirit

- President Xi called for renewing the ancient Silk Road spirit of ‘peace and cooperation, openness and inclusiveness, mutual learning and mutual benefit’.

- Reviewing progress made during the past four years

- Fruitful results have been achieved in the areas of policy coordination, infrastructure, trade, finance and people-to-people exchange.

- For example, China has signed cooperation agreements with over 40 countries and international organizations; total trade between China and other Belt and Road countries in 2014-2016 has exceeded US$3 trillion, and China’s investment in these countries has surpassed US$50 billion; the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank has provided US$1.7 billion of loans for 9 projects in Belt and Road countries.

- Reiterating China’s objectives

- ‘We are ready to share practices of development with other countries, but we have no intention to interfere in other countries’ internal affairs, export our own social system and model of development, or impose our own will on others.’

- ‘We will not resort to outdated geopolitical maneuvering. What we hope to achieve is a new model of win-win cooperation. We have no intention to form a small group detrimental to stability, what we hope to create is a big family of harmonious co-existence.’

- Reaffirming the aim and focus of the Initiative

- ‘The pursuit of the Initiative is not meant to reinvent the wheel’, but ‘to complement the development strategies of countries involved by leveraging their comparative strengths’.

- The Initiative should ‘focus on the fundamental issue of development, release the growth potential of various countries and achieve economic integration and interconnected development and deliver benefits to all’.

- ‘We should build an open platform of cooperation and uphold and grow an open world economy.’

- Pledging more funds for the Initiative

- China’s Silk Road Fund will increase funding by 100 billion yuan; Chinese financial institutions will set up overseas RMB fund business with an estimated scale of around 300 billion yuan; the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China will make special loans worth 250 billion yuan and 130 billion yuan, respectively, to support cooperation in infrastructure, industrial capacity and financing.

- China also promised assistance worth 60 billion yuan to developing countries and international organizations over the next three years. Some other financial assistance will be provided to improve the well-being of people in the Belt and Road countries.

- Enhancing trade and cooperation

- China will host the China International Import Expo starting from 2018.

II. Major deliverables of the Belt and Road Forum

President Xi and 29 other heads of state and government signed a joint communique [2] at the close of the Leaders Roundtable held on the second day of the forum, reaffirming their commitment to building an open economy, ensuring free and inclusive trade, and promoting a universal, rules-based, open, non-discriminatory and equitable multilateral trading system with WTO at its core.

The two-day forum yielded fruitful results with 270 deliverables in five key areas, namely policy coordination, infrastructure, trade, finance as well as people-to-people exchange, according to a list of deliverables released by the Xinhua News Agency. During the forum, China signed cooperation agreements with 68 national governments and international organizations. Below are some of the major outcomes/deals achieved during the BRF [3]:

- Policy coordination

- The Chinese government signed bilateral cooperation agreements with 16 other national governments/relevant ministries and several international organizations.

- The Guiding Principles on Financing the Development of the Belt and Road was endorsed by the ministries of finance of relevant countries.

- An advisory council, a liaison office, and the Facilitating Centre for Building the Belt and Road will be set up. The official Belt and Road web portal and the Marine Silk Road Trade Index have been launched.

- Infrastructure connectivity

- Bilateral cooperation agreements in various fields such as energy, water, ports, railways and information technology, were reached between relevant government departments.

- Agreement for Further Cooperation on China-Europe Container Block Trains among Railways of China, Belarus, Germany, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Poland and Russia was endorsed by railway companies of relevant countries.

- The China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China signed financing agreements on various infrastructure projects with parties of relevant countries participating in the Initiative.

- Trade connectivity

- The Chinese government signed economic and trade cooperation agreements with the governments of 30 countries.

- The Ministry of Commerce of China and the relevant agencies of more than 60 countries and international organizations jointly issued the Initiative on Promoting Unimpeded Trade Cooperation along the Belt and Road.

- The China-Georgia Free Trade Agreement was endorsed.

- Bilateral cooperation agreements in the fields of promoting SME development, agriculture trade, e-commerce, inspection and quarantine, cross-border economic cooperation zone, etc. were signed between China and government departments of relevant countries.

- The China International Import Expo will be held from 2018.

- Finance connectivity

- In addition to the funding pledges made by President Xi in his speech, China will set up the China-Russia Regional Cooperation Development Investment Fund, with a total scale of 100 billion yuan and the initial scale of 10 billion yuan.

- The Ministry of Finance of China signed memoranda of understanding on collaboration under the Initiative with six international development organizations.

- The China-Kazakhstan Production Capacity Cooperation Fund came into operation.

- The China Development Bank, the Export-Import Bank of China, and China Export and Credit Insurance Corporation signed cooperation agreements with relevant parties of countries participating in the Initiative.

- People-to-people exchange

- On top of the 60 billion-yuan financial assistance announced in President Xi’s speech, China will provide 2 billion-yuan emergency food aid to the Belt and Road countries, US$1 billion to the South-South Cooperation Assistance Fund, and US$1 billion to relevant international organizations to implement projects benefiting countries along the Belt and Road.

- Bilateral cooperation agreements on various fields such as cultural exchange, tourism, education, science and technology, health, media exchange and think tank exchange were signed between Chinese government departments and relevant parties of other countries along the Belt and Road.

- The Chinese government endorsed assistance agreements with multiple international organizations.

III. Shaping inclusive globalization with worldwide participation

Over the past four years, the Belt and Road Initiative has won warm response and made practical achievements, while challenges and misgivings such as financing gap, transparency, and economic viability of projects largely remain. The launch of the BRF has provided a great occasion for all participating parties to review progress, gather consensus, develop mechanisms, and cultivate deeper and broader cooperation. The concrete and extensive deliverables produced, especially China’s promise of more funding, have boosted the optimism about the Initiative’s prospects.

Amid mounting concerns over rising protectionism and isolationism, the BRF is an important political event for promoting the Belt and Road Initiative as a new platform for mutually beneficial collaboration and inclusive globalization. The joint communique, which was signed by 30 heads of government led by China, signals that developing countries have become a driving force of free trade and open economy.

Notably, the presence of delegations from the US and Japan, who were previously indifferent to the forum, turned out to be a last-minute surprise. In fact, many developed economies, including Germany, France, Canada and the post-Brexit vote UK, sent delegations to the forum, even as diplomats confessed they knew little about the massive integration strategy. The unprecedented attendance by both developing and developed countries has not only transformed the China-led Initiative into a truly open platform with global recognition, but also marked a significant milestone in China’s rise as a diplomatic superpower at the world stage.

Please click to read the full report.

[1] For the full text of the speech, please see http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-05/14/c_136282982.htm

[2] Joint Communique of Leaders Roundtable of Belt and Road Forum, https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/zchj/qwfb/13694.htm

[3] For the full list of deliverables, please see https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/qwyw/rdxw/13698.htm

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Fraser Cameron and Rui Yan, EU-Asia Centre

Introduction

Why OBOR? There are different motives to explain the OBOR initiative. Some view it as a means for China to deal with its over-production capacities, to reduce regional imbalances by promoting economic development in the Western part of the country, and to utilize its vast, albeit declining, foreign exchange reserves to secure access to new sources of raw materials and promote new markets for Chinese goods. Some consider it will improve China’s energy security while others see it as a master-plan to increase Chinese influence at a time when American leadership in Asia is questioned. China should also gain more influence in Central Asia, often viewed as Russia’s backyard. Some see it as a clever attempt to divert attention from Chinese activities in the disputed South China Sea. Others take a more altruistic view comparing it to the Marshall Plan launched by the US after the Second World War to help restore the battered economies of Europe.

To date there has been very little detail about OBOR from the Chinese side and Chinese officials and experts have been struggling to define the concept and to come up with concrete projects. There is no deadline and there seems to be no exact geographical confines with projects in Africa, Australia and even Latin America all being placed under the OBOR umbrella. There is also an attempt to include free trade agreements that were started long before the OBOR initiative. On the European side there has been a cautious welcome for OBOR but political and business leaders have been waiting for evidence of concrete projects, which they could support. What is clear is the huge interest in OBOR with close to 100,000 articles about OBOR appearing in the past four years. This article reviews how OBOR has been presented and received in China and Europe and assesses its potential to strengthen EU-China relations.

Conclusion

OBOR has a strong domestic context helping the CCP to buy time in order to reform the unsustainable social and economic model. Although OBOR has never been defined, which is perhaps a plus, it continues to enjoy strong support at the highest levels in China although there are some experts who doubt that it will continue to receive the same priority after President Xi leaves office. European opinion is more cautious and waiting to see whether concrete projects materialize. For countries along the route OBOR is generally viewed with positive eyes. AIIB president Jin Liqun estimates that Asian countries need around $8 trillion in expenditure by 2020 just to reach the world average. The AIIB has already issued loans of $1.73bn to nine infrastructure and energy projects in seven OBOR countries. OBOR also ties in with the connectivity aims of the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) and it would be useful to explore possible synergies. Equally there are several EU projects in central Asia (Inogate, Traceca, Bomca) that could be linked to OBOR.

OBOR is a grandiose initiative but there are many potential pitfalls and it is clear that far greater attention should be paid to political risk analysis for the successful implementation of OBOR. Some 70 countries have already joined the initiative and many have enjoyed a boost in trade with China. But many are under-developed countries and often demand Chinese commitment to bring in advanced technology regardless of their development stage. China’s shrinking foreign exchange reserves and the falling value of its currency may also affect the initiative. The Chinese should be wary of over-selling OBOR. Some official commentaries have tended to exaggerate the achievements to date.

Shared interests have led to China-Europe cooperation on OBOR. The popularity and success of OBOR initiative will depend not only on the economic gains and benefits, but also on successful cooperation on issues linked culture, tourism and people to people exchanges. The vision for OBOR is ambitious, but if well implemented, it has the potential to benefit the various countries and societies along the road, not least in promoting sustainable development. It could also have a major impact on EU-China relations.

OBOR is thus an ambiguous tool of Chinese domestic and foreign policy. It is powerful example of Chinese soft power. How China develops OBOR will help define the very nature of China as an actor in the 21st century OBOR will certainly be watched closely by the EU both for synergies to participate and to guard against threats to European interests. It has considerable implications on the political, security, trade, financial and environmental fronts. The EU will have to consider the best approach to engage with China in order to maximise synergies but one thing is clear – OBOR will figure as a major item in EU-China relations for the foreseeable future.

Please click to read the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Wu Shang-su & Alan Chong – S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Synopsis

The fanfare surrounding the pioneering China-Europe container express train that completed a one-way journey between 1-18 January 2017 is only partially warranted. Frictions abound over issues of inter-operability of railway gauges and the diplomacy of connectivity as China pushes ahead with its massive One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative.

Commentary

THE FIRST transcontinental railway between China and Europe arrived in London on 18 January 2017, exactly 18 days after it began its journey of 12,000 kilometres from Yiwu in eastern Zhejiang province, with its cargo of garments, bags and other consumer goods. The train carrying 24 containers pulled by a German Deutsche-Bahn locomotive for its final leg, transited Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, Poland, Germany, Belgium and France before arriving in Britain. A comparable journey by sea would take 30 days or more though carrying a staggering 20,000 containers.

The steel railroad across the Eurasian heartland symbolising the new overland Silk Road – officially known as the Silk Road Economic Belt – partly realises the “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR) vision of China, and includes the many high speed rail projects embraced by much of Asia in the past decade. While the pioneer freight train service was welcomed with much fanfare in Britain and China, in reality, a number of obstacles lie on the less than smooth Silk Road.

Different Gauges and Operators

Several factors currently limit the effectiveness of the railway’s potential in achieving Beijing’s goals. The dozens of existing rail links are not actually inter-connected at the moment. The rail systems in Kazakhstan, Russia, and Belarus use a wide gauge of 1.52 metres, a Soviet legacy, while the Chinese and European systems use a standard gauge of 1.435 metres.

This means that the cargo has to be physically transferred between trains whenever crossing between the two regions of gauges, which occurs at least twice during the journey. Despite the effort of China or its Swiss contractor in managing travel time, additional costs would be unavoidable, and those Chinese products transported through rail would be in an inferior position in the market, in contrast to the volume conveyed through shipping.

Transferring cargo inevitably increases travel time and encourages the use of freight in standard containers, while discouraging transportation of bulky cargo such as agricultural crops and some types of heavy machinery. Those kinds of bulk cargo may be more competitive for landlocked countries to trade rather than manufactured or processed merchandise in containers. Intercontinental freight services have therefore not significantly improved the geo-economic position of those landlocked countries in the global market.

Currently, rolling stocks of variable gauge axles (VGA) for trains running on different gauges, especially transferring between the standard and wide gauges, are available in several European countries, including freight services. However, such expensive and complicated designs, mainly reserved for passenger trains, remain impractical for numerous freight trains and do not present an economic solution for China.

Although China may introduce VGA technology for local manufacture to lower costs, the deployment of VGA would logically multiply refurbishment and transportation costs on the entire overland Silk Road.

Stumbling Over Soviet Era Gauge System

Technically, the rail lines in the former Soviet republics could be transformed into a dual gauge system but that would mean higher costs both in the initial modifications and in the ensuing maintenance. Apart from tracks, different technical criteria, such as signal and electrical systems as well as standards of curves and slopes, make dual-gauge construction more difficult than adding one rail.

Beijing may not be willing to shoulder the expense. Furthermore, the wide gauge system was designed by Tsarist Russia to deny any potential foreign invader any logistical convenience. This fact remains a significant strategic concern.

Therefore, the governments which use the wide gauge may not want to abandon this arrangement, as the standard gauge tracks connect not only to China but also to Western Europe.

Diplomacy of Connectivity

The dependence upon transferability between different rail systems also means that ‘diplomatic grease’ must be applied all along the new Silk Road. Sovereign railroad authorities must cooperate in approving licences, coordinating timetables, arranging adequate engines and other operational matters for the transfer of cargo and rolling stock. National and privatised rail companies ought to establish reliable and open protocols for communication regarding not only cargo transfer but also safety regulations.

Finally, the political assurance of uninterrupted rail transit must be guaranteed as far as possible if business interest is to be sustained. This may be a great deal to ask for considering that Central Asian states still have to consolidate their governance in regard to containing separatist movements, insurgencies and the rule of law. If the new Silk Road is to live up to its promise, diplomatic grease is the final necessary and sufficient ingredient.

For now, it looks like the other half of OBOR – the Maritime Silk Road – could have a relatively smoother sail. It will have to admit transit by ships of all registrations and ownerships, and on internationally recognised waters through the South China Sea, the Straits of Malacca through the Indian Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. It also has to retain a more democratic, flexible and politically accommodating edge over rail transport through the Eurasian heartland.

For politicians, citizens, businessmen and rail companies alike, the new Silk Road requires much more work to establish its credentials as a credible alternative to the time honoured efficacy of maritime trade transit. On a slightly more positive note, the new services would suggest tighter and shorter direct rail links between China and its trading partners in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), which may prove more crucial for the ultimate feasibility of the One Belt, One Road vision.

Please click to read the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Richard Ghiasy and Jiayi Zhou – Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (sipri)

China has long posited that common security can be propelled and buttressed through economic development and cooperation. Infrastructure, in turn, is one of the essential foundations of economic development and cooperation – no economically prosperous state has been able to progress without it. As the Chinese put it ‘要想富, 先修路’ (‘if you want to be rich, first build a road’).

Large parts of Asia have a critical lack of basic infrastructure such as roads, rail tracks, bridges, airports and power grids, which current national and multilateral developmental institutions are unable to address. This infrastructure deficit is an estimated $4 trillion (pdf) for the period 2017-20 alone. China intends to reduce this deficit in Asia, and in parts of Europe, through the Silk Road Economic Belt (the ‘Belt’) component of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The Belt has, therefore, quite deservedly been received with enthusiasm among many states of the Eurasian continent since its proposal in 2013. It is an ambitious multi-decade vision to physically, digitally and culturally connect Eurasia, pursue closer Eurasian economic cooperation and mitigate poverty. This grand vision has become a pillar of the President Xi Jinping administration’s foreign policy.

Opportunities and challenges

Foreign policy is always an extension of domestic interests and the Belt intends to serve a wide range of Chinese interests. These include enhancing China’s economic security by increasing its global economic and financial clout, and mitigating current and possible future security threats emanating from its neighbours by promoting their economic growth and subsequent closer economic ties with China. Simultaneously, the Belt is a useful platform to channel China’s surplus production capacity and surplus capital outwards.

As the Belt is a major public goods provider, it could indeed become one of the cornerstones of Asian economic growth and integration. Concurrently, it could lead to closer political and even security cooperation between China and the participating states and among the participating states themselves. Yet, the pathway towards this future is still fraught with obstacles. These include political and popular suspicion of China’s intentions behind the Belt, geopolitical competition, Chinese financial overextension, and lack of local governmental interest and capacity to tap Belt projects for the benefit of the broader population.

Tied to this latter obstacle is the question of to what extent the Belt actually fits into the on-the-ground political and socio-economic realities of participating states. Improved infrastructure can certainly serve as a catalyst for employment and economic activity, but tapping its developmental potential also requires local states’ investment in human and institutional capital, augmented by smart economic policies.

The Belt is an innately political process: many participating states have low levels of political accountability and high levels of corruption, and Chinese investments do not come with corresponding governance reforms to transform these systems. In addition, there may be physical security threats to implementation of the Belt in the form of general political violence or even more targeted attacks against Chinese projects. The Belt will inevitably be impacted by but also interact mutually with these dynamics.

Interaction with security dynamics in Central and South Asia

The Belt fits well into China’s own security concepts, which stress common security through economic cooperation. The Belt will certainly expand China’s overseas interests and will require China to take a robust position on regional security affairs, not least to protect its investments. Thus, China’s non-interference stance, which has already been evolving over the past few years, will likely become much more ‘creative’ as a result of the Belt.

Indeed, China’s evolving stance can already be witnessed in Central and South Asia, where notable examples include the Quadrilateral Cooperation and Coordination Mechanism to combat terrorism established between the armed forces of China, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Tajikistan in August 2016; the stepping-up by China of military cooperation and security assistance to states participating in the Belt; and the ‘outsourcing’ of military protection of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) – the main Belt corridor in South Asia – to Pakistan.

More broadly, the Belt will interact with Central and South Asian security dynamics in a mutually constitutive way. In Central Asia, it is perceived by the landlocked Central Asian regimes as a means of boosting economic growth, which will have positive spillover effects on security. At the regional level, the financial prospects the Belt offers could also serve to stimulate greater regional cooperation on the range of issues these states face.

However, in South Asia, where the Belt currently only really runs through Pakistan, it has raised regional political temperatures. India has objected to CPEC in the strongest terms (pdf), in part because it traverses territory that is disputed between India and Pakistan. CPEC has exacerbated the pre-existing India-Pakistan rivalry, as well as China-Pakistan competition with India over regional influence and security.

India is concerned about the long-term geopolitical implications of CPEC, particularly that China will gain more regional influence at the expense of India. India fears that investment protection and protection of future transit through Pakistan will increase China’s security role in South Asia, and has concerns about a possible naval base in the port city of Gwadar in Pakistan, one of the BRI’s key strategic investments.

Afghanistan, in contrast to India, welcomes the Belt, but the country’s instability and difficult ties with Pakistan will deter it from becoming an established Belt participating state – at least for the foreseeable future.

A stabilizing or destabilizing influence?

In both Central and South Asia greater economic growth brought by Chinese investment could provide the conditions for increased development and stability. A case in point is that the majority of current CPEC projects focus on improving Pakistan’s electricity grid, important for a country that is plagued by structural power cuts. China hopes that CPEC might instil a ‘change of mindset’ in Pakistan: one that is increasingly oriented towards utilitarian economic development.

However, there are also concerns that Chinese capital could exacerbate some of the structural governance problems in Central Asia and Pakistan, particularly those pertaining to corruption and lack of accountability. In this regard, it could also further entrench a political elite that have proven inept at providing human security and welfare.

It is yet to be seen how these dynamics unfold but it is certain that investment alone will not be sufficient to bring about transformative development to Central Asia or Pakistan. Inclusive and long-term sustainable growth will require institutional reform to address patrimonial practices and state corruption. Central Asian governments and Pakistan will need to prioritize good governance and long-term, inclusive economic growth in addition to short-term economic gains.

Much of the asserted positive spillovers of the Belt therefore still strongly depend on the practical implementation of the Belt, the distribution of the spoils, and how human security in addition to regime- and state-centric security is emphasized and addressed.

This said, it is important to note that most local sources of insecurity in Central and South Asia exist with or without the presence of the Belt. They are not easily resolved of their own accord, and the Belt does at least address a vast Eurasian deficit in infrastructure and economic integration that has few or no large-scale financial alternatives.

The Belt is, at the very least, an opportunity to begin to think about and address these common challenges in pursuit of sustainable development.

This topical backgrounder is based on the report ‘The Silk Road Economic Belt: Considering Security Implications and EU-China Cooperation Prospects’ published by SIPRI and Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES). The report concludes a year-long project that analysed Chinese, Russian and English sources and interviewed 156 experts, including academics, journalists, policy advisors and policymakers in 7 countries throughout Eurasia.

Please click to read the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Promoting the Development of Overseas Co-operation Zones: Hong Kong’s Role and Opportunities

From the above cases of economic and trade co-operation zones in Asia, it is apparent that they are beneficial to the “going out” of mainland enterprises to develop overseas business and expand sales opportunities in Belt and Road markets. They are also beneficial to enterprises in fine-tuning their overall production layout by making use of local labour forces and other advantages in concert with existing production activities on the mainland. Meanwhile, with increases in investment and production in Southeast Asia, a regional supply chain network that connects to China has gradually taken shape and is getting increasingly tight-knit and complex, promoting commercial logistics and trade development in the process.

In the course of their development, these co-operation zones can also provide Hong Kong with outbound investment opportunities. An overview of the cases mentioned above indicates that manufacturers and traders in Hong Kong, particularly SMEs, can consider using these co-operation zones as platforms to forge into respective local markets or to set up a base to capitalise on local production advantages to expand into the international market. Those in Hong Kong engaging in housing and infrastructure construction, transportation (including container terminal planning and operating), warehouse management and logistics can also consider collaborating with the co-operation zones through investment or providing related services to facilitate the sustained development and competitive advantages of the zones concerned.

Challenges Facing the Zones and Hong Kong Services

According to a study report published by the World Bank[1], many of the numerous special economic zones and industry parks (inclusive of industrial parks and science parks) around the world fail to develop sustainably. The success or failure of the development of an industry park is dependent not solely on the investment policy and preferential terms offered by the respective host country or region. It also depends very much on factors such as the site location, planning and design, as well as the level of management of the park in question.

This is particularly so because, as competition is intensive among different countries or various regions of the same country, the corporate-tax incentives offered by parks are basically similar. Therefore, an over-reliance on preferential tax treatment but a lack of effective communication and co-ordination between the government and the stakeholders of a park may lead to a poor connection between the park and the surrounding traffic networks as well as an undesirable labour supply and other supportive and promotional services. This would, therefore, be the main obstacle to an industry park’s sustained development and corporate investment.

In the early stages of developing special economic zones and industry parks, some South-east Asian countries have been concerned mostly with promotional activities to attract enterprises and investment, neglecting to establish a set of clear and sound legal and regulatory systems. Such systems would include a co-operative framework for joint public-private development of the zone or park, the specific rights and responsibilities of a zone/park developer and operator, a zone/park design aligned with the planning and infrastructure construction in peripheral cities, and environmental protection and emissions standards.

In the early years in some countries such as Vietnam, in their eagerness to attract private developers to participate in the development of industrial parks, local governments were reliant on signing investment contracts with individual developers without a standardised overall negotiation framework. This led to a large disparity in preferential or concession treatments, resulting in vicious competition among parks and affecting the processes of approving individual local investment projects by the state-level departments concerned. In some cases, even after an investment had been committed, when a project was found to be inconsistent with local conditions or affecting other sectors or economic aspects, the government would only then impose additional restrictions or demand the reopening of negotiations, increasing the investor’s costs and directly affecting the sustainable development of the whole project.

To ensure that special economic zones and industry parks would better serve their purposes – such as attracting investment, creating jobs and driving industrial upgrading – and that the targets of the 2025 development blueprint of the ASEAN Economic Community could be achieved, the ASEAN countries reached consensus at the ASEAN Ministers’ Meeting in August 2016. They agreed to adopt the ASEAN Guidelines for Special Economic Zones Development and Collaboration to serve as a basis for the effective planning and regulation of future zones and industry parks.

Referring to the above case analyses of industry parks in Vietnam, Cambodia and Malaysia, we now attempt to explore possible roles for Hong Kong in promoting the development of China’s overseas co-operation zones regarding location selection, planning/design and management.

Investment Analysis and Due Diligence

The 10 ASEAN countries are not only very different in their economic and population structures, but also in their labour markets, wage levels, stages of economic development, investment policies and in the incentives they offer. Though most ASEAN countries are using industry parks as the main vehicle to drive economic development and attract investment, there are substantial differences in the actual production environment and conditions among individual parks. These include, for example, the park’s location, conditions of the local supply chain, the standards of logistics facilities and services in peripheral areas, the efficiency of inland and international transportation, environmental requirements, the adequacy of skilled and unskilled labour supply, local training of skills and management personnel, etc. All these issues will eventually affect the sustained development capability and competitiveness of a zone.

Therefore, when carrying out investment planning and selecting a location, an investor must properly evaluate the country, the region and the policies concerned to ensure that the development of the zone will align with the local medium- to long-term development plan. This will minimise the hidden risk that an investment project may not have the blessing of the government, and will avoid the difficult scenario of having to co-ordinate and negotiate with the local government to obtain policy incentives and other support. Nevertheless, most enterprises say they do not have sufficient knowledge about the politics, culture and legal regimes of the relatively backward investment locations along the Belt and Road routes, including some of the ASEAN countries. Their problem is compounded by the fact that information is less than transparent in these countries, so it is difficult to ensure that an investment project is in compliance with the legal requirements of the country concerned, or to assess the medium- to long-term benefits and potential risks of the investment in question. Therefore, there is a need to seek professional services support.

Hong Kong’s service providers in this field are not only familiar with the legal and investment regimes of advanced countries, but can also utilise their extensive international networks in carrying out effective risk assessment for mainland enterprises intending to invest in emerging or Belt and Road countries. They can also offer strategic recommendations regarding the feasibility of an investment project, and can conduct special surveys on key or sensitive issues such as the environmental policy and tax incentives of an investment location. This can help investors control risks and ensure the sustainable development of a project after an investment has been made.

Zone/Park Planning and Management

The United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) estimates there are more than 1,000 special economic zones in the ASEAN region, of which 893 are industrial parks. In Vietnam alone, there are more than 320 manufacturing-oriented industrial parks. As approximately half of the foreign direct investments entering Vietnam have ended up in industrial parks, competition among them is very keen.

Some industrial parks in Asia are designed so poorly that overcrowding and traffic congestion are common, while a number of old-style park premises lack green spaces and lifestyle recreation facilities, all indirectly leading to a host of labour, pollution and social problems. At the other extreme, some industrial parks are developed so ahead of time that their size and facilities far exceed actual demand. Consequently, enterprises setting up operations in these parks must bear very high management fees, unless they obtain subsidies from the government or the developer.

Furthermore, the designated new economic zones or industrial parks in some emerging countries are located in relatively remote areas in order to play a leading role in regional development and growth. Investors and developers in such cases not only have to concern themselves with the development of these zones, but they must also handle and provide transportation and other infrastructure to connect them to peripheral areas and the main ports.

Take Vietnam’s Longjiang Industrial Park as an example. In response to the expected opening of the Ho Chi Minh City-Trung Luong Expressway in 2010, the management company of the park had been upgrading its internal road system in earnest, as well as speeding up negotiations with the local government to facilitate road construction connecting the park to the expressway and to raise its overall transportation and logistics efficiency.

Hong Kong is a hub for infrastructure and real property services boasting more than 2,100 world-class companies engaging in architectural design, surveying and engineering services. These companies have a lot of experience in developing Hong Kong and overseas businesses and are capable of supporting the mainland in developing various types of industry parks overseas by offering a comprehensive range of project consultancy and management services. These include strategic recommendations in architectural design, project supervision, government-developer collaboration, infrastructure development, sewage and waste treatment, etc. Even for projects as large as the East Coast Economic Region in Malaysia, Hong Kong’s services sector can help add value and inject sustainable development planning concepts through their experience in participating in the development of large-scale integrated communities and the integrative utilisation of infrastructure and land.

|

Hong Kong Experts Participate in Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor Project AECOM provided full programme management services for the Dholera Special Investment Region (DSIR) as part of the Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor (DMIC) Development Corporation’s new cities infrastructure programme. The programme aims to transform India’s manufacturing and service base by developing a number of smart, sustainable and industrial cities along the 921-mile corridor between Delhi and Mumbai, the first to be developed being the 347-square-mile township of DSIR. AECOM’s project scope consists of implementing all base infrastructure including water supply, sewerage, roads, highways, power and rail; performing extensive flood-control and drainage measures to protect the future city; and overseeing the development and execution of all public-private partnership delivered projects, such as the railway connecting Ahmedabad to Dholera, industrial waste-water treatment and a potable water-treatment plant. In the process of developing new towns in Hong Kong, AECOM’s experts had to overcome the land constraints and technical challenges while being able to appreciate the needs of these developments at various stages, from engaging stakeholders, conceptual designs to construction, enhancement to completion, and finally making the entire project more resilient within a short timeframe. The unique experience, advanced technology and knowledge used can be readily put into practice in the Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor. [The Hong Kong specialists of AECOM have also participated in a number of ASEAN infrastructure projects. For details, please visit AECOM’s website at www.aecom.com/hk/about-aecom/]. Remark: The above case is published on HKTDC’s Belt and Road web page: www.beltandroad.hktdc.com/ |

As far as the management of zones and parks is concerned, it should be noted that ASEAN’s guidelines for developing and co-operating in special economic zones permit that the developer and operator of an industry park can be different entities. Professional operation services providers offer management and real properties letting services, public utility services such as water and power supply, as well as waste and sewage treatment. They can also offer a host of value-added services such as the setting up of training centres and the provision of services in healthcare, childcare, transportation and employee recruitment.

In Hong Kong, other than local professional real property management service companies, there are also a large number of major international management services companies and consultancies. In addition to providing outstanding management and operation services, these companies are also in a position to recruit clients and match partners for zones and parks through their transnational client networks.

It is highly advantageous for the development of an industry cluster if a park can identify a suitable anchor investor that matches its positioning. The SSEZ has now attracted an industry cluster of about 100 enterprises from the mainland, Europe, the US and Japan that are engaging in textiles, light-industry products and accessories.

Environmental Protection Services

Belt and Road countries are mostly low- to medium-developing economies, but as they gradually industrialise, more and more of their residents are concerned about the resultant pollution. This has forced government planners and developers to pay more attention to environmental protection in industry related projects, and environmental assessment has become one of the investment requirements in many co-operation zones.

As these zones are mostly established in undeveloped or rural areas, industrial development will inevitably impact on the environment. Residents close to some co-operation zones have staged protests against the pollution brought about by mainland enterprises, impacting the zones’ long-term development. Moreover, planning and building environmental protection infrastructure takes time and requires adequate funding. Should the building of such infrastructure lag behind the zones’ development projects, irreparable environmental and pollution problems may result.

Hong Kong’s environmental-protection firms are adept at providing international-standard services in sewage treatment, pollution control and resource economisation. They are also experienced in advanced environmental management and enjoy a good international reputation. Hence they can provide the co-operation zones concerned with various types of environmental services as well as environmental assessment, environmental protection architectural/system design and related advisory services that are in compliance with the standards in advanced countries.

Production and Logistics Services

Belt and Road countries are mostly lacking in key production materials as well as other industrial materials and parts/components. Nor do they have enough skilled workers, technicians and engineers. While on the one hand they have to rely on the importation of certain materials to support production and operations, on the other hand they need different types of skilled personnel to provide production technology support. By virtue of its extensive international logistics network, Hong Kong is capable of effectively linking up goods transportation networks in mainland China, in Belt and Road countries and other important production bases, providing access to the huge production material support from the mainland and from within the region. Moreover, because of its ready supply of personnel in technology application and production technology, and also because of its convenient transportation network, Hong Kong can at any time provide extensive key parts and components, industrial materials and technological support to the production facilities set up by mainland enterprises in the Belt and Road co-operation zones.

|

Demand for Integrated Logistics Services Kerry Logistics (HK) Ltd points out that as ASEAN’s economy is becoming increasingly buoyant and mainland enterprises often choose to invest in factories in the ASEAN market as part of their “going out” strategy, the demands of ASEAN and mainland enterprises operating there for logistics and transportation services is bound to rise rapidly. In a move to effectively serve ASEAN and mainland clients, Kerry Logistics, as a pioneer service provider in cross-border transportation in ASEAN, has launched Kerry Asia Road Transport (KART), an overland cross-border transport network linking ASEAN countries and China, to supply high-efficiency long-haul overland transport and door-to-door delivery services. (Note 1) As the pioneer in creating an ASEAN-wide cross-border road transportation network, Kerry Logistics has successfully linked Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar directly with mainland China. It provides customers with long-haul trucking as well as sea-land and air-land services in these geographically challenging areas. (Note 2) In its recently announced 2016 annual results, Kerry Logistics says its business in other parts of ex-Greater China reported healthy performance. Kerry Logistics’ express business, which covers Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia and Cambodia, continues to capture growth opportunities arising from increased intra-ASEAN e-commerce volume and cross-border logistics activities. (Note 3) Note 1: For further details, please see HKTDC research article (September 2015): Hong Kong Services for Mainland’s Outbound Investment (5): High-end Logistics Services Help Bolster International Business Expansion Note 2: Source Note 3: Source |

Furthermore, as supply chains become increasingly globalised, responsive and efficient, enterprises have to meet their stringent logistics and distribution requirements. Therefore, industrial parks that want to attract enterprises to invest in developing industry clusters have to plan and develop relevant transportation and logistics services.

MCKIP in Malaysia is an example in point. Since it is in collaboration with Kuantan Port to set up a bonded area to attract investment in export-oriented heavy industry and high-tech industries, the future development focus of Kuantan Port is to upgrade its container handling capability and improve its port logistics services. Hong Kong’s logistics services providers have extensive experience in the design of operational processes and the management of operational systems and IT for container terminals. In fact, they have practical experience and track records (including participation in the development of Shenzhen Special Economic Zone) in utilising related infrastructure support, equipment layouts and advanced operational processes in enhancing the overall operational efficiency of ports. Therefore, they are well qualified to offer help to Kuantan Port in developing the business of transporting goods and containers internationally.

Financing and Insurance Services

Enterprises are the main investors in the industrial zones developed overseas by China. Although zones that have passed required assessments are qualified to receive special subsidies and financing services, most funding would still have to be raised in the market. Hong Kong is one the world’s three major international financial centres, and funds are available from various sources and a wide range of financing products. As such, Hong Kong is in a position to match and accommodate funds and meet the insurance needs of different maturation, exchange rates and asset risks.

Adding to this are Hong Kong’s advantages in being an important business platform in the Asia Pacific with a sound legal system, free-flow of capital and information, and a full complement of professional services in law, accounting, etc. In investing in Belt and Road countries, mainland enterprises can make use of Hong Kong’s professional project evaluation and sustainability assessment services to bring in external funds to finance their overseas investment projects and other business ventures. They can also set up a regional office in Hong Kong and capitalise on Hong Kong’s highly efficient business environment to co-ordinate investment projects in mainland China, Asia and Belt and Road countries to enhance overall operational efficiency.

Furthermore, Hong Kong’s services platform can offer different investment options to mainland enterprises, including the use of private-equity investment funds. As a way to diversify risks, mainland investors can also make use of Hong Kong’s international network to identify offshore partners to carry out equity joint investment and other joint-stock co-operations. Mainland enterprises can also make use of their investment partners’ advantages to overcome their own limitations. By generating synergy between their partner’s advantages and their own knowledge and expertise, they can expand the business scopes of their Belt and Road investments.

Conclusion

Over the years, Hong Kong’s service providers have helped many mainland enterprises handle trade and investment business in Hong Kong and overseas markets. In supporting the overseas investment of mainland enterprises, Hong Kong has definite advantages. These include the availability of a full range of international standard professional services in finance, law, taxation as well as risk assessment in sustainable operation and international certification and testing.

As such, Hong Kong is an important springboard from which mainland enterprises can make overseas investments. As the mainland implements the Belt and Road Initiative and encourages the “going out” of enterprises to invest overseas, outbound investment activities, including investment in setting up Sino-foreign co-operative industrial parks, will become increasingly common.

Although mainland enterprises have definite advantages in the general contracting of projects, Hong Kong’s related professional and business services excel when it comes to specialised project segments. Hong Kong also has extensive international experience and is particularly strong when it comes to grasping and analysing overseas information. Therefore, strengthening co-operation between Hong Kong’s services sector and mainland enterprises would be beneficial to promoting China’s overseas economic and trade co-operation zones.

Please click here to purchase the full research report.

[1] Special Economic Zones: Performance, Lessons Learned and Implications for Zone Development, Akinci G and Crittle J, 2008, World Bank

Belt and Road: Development of China’s Overseas Economic and Trade Co-operation Zones (1)

Belt and Road: Development of China’s Overseas Economic and Trade Co-operation Zones (2)

Belt and Road: Development of China’s Overseas Economic and Trade Co-operation Zones (3)

Belt and Road: Development of China’s Overseas Economic and Trade Co-operation Zones (4)

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Malaysia-China Kuantan Industrial Park in Malaysia

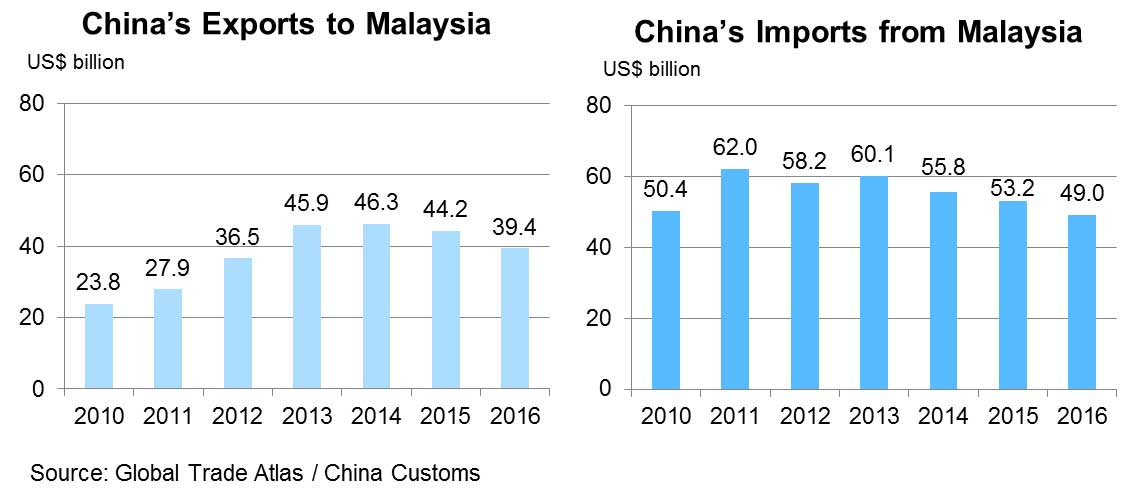

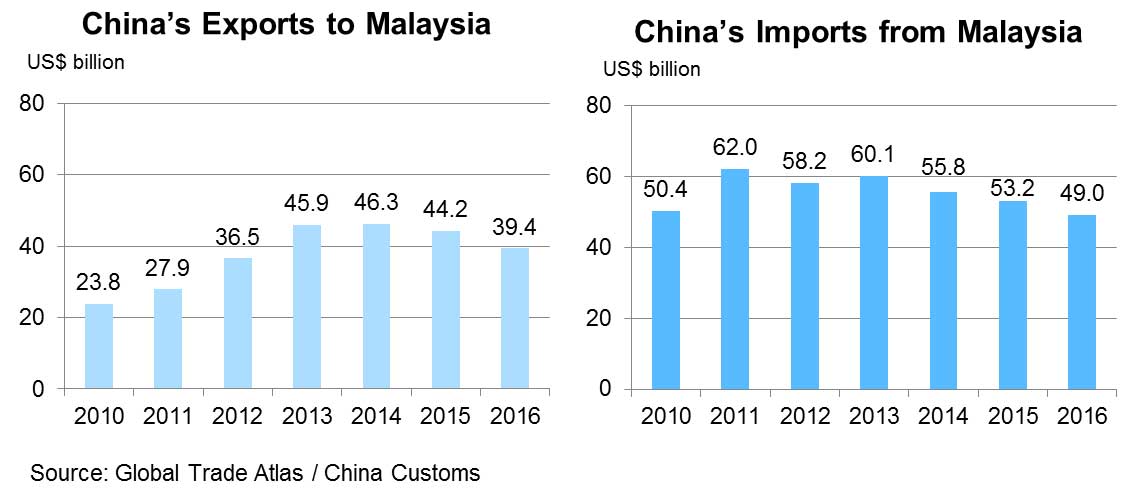

Malaysia, as a major ASEAN economy and an important gateway along the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, is strengthening its industrial co-operation with China. Industrial parks have been established in Qinzhou in China’s Guangxi Autonomous Region (the China-Malaysia Qinzhou Industrial Park), and Kuantan in Malaysia (Malaysia-China Kuantan Industrial Park, MCKIP). Through this “two countries, twin parks” model of co-operation, China and Malaysia hope to strengthen regional supply chain management, push forward the development of industrial clusters, and promote trade and investment between the two countries. The “Port Alliance” will also be established to improve customs efficiency and expedite trading between the two countries through experiments on joint customs clearance, information sharing and other mechanisms. Malaysia is among China’s largest trading partners and major investment destinations in ASEAN, with the volume of bilateral trade reaching US$88.4 billion in 2016.

MCKIP is a bilateral Malaysia-China government-to-government collaboration. MCKIP Sdn Bhd (MCKIPSB) is a 51:49 joint venture between a Malaysian consortium and a Chinese consortium. IJM Land holds a 40% equity interest in the Malaysian consortium; together, Kuantan Pahang Holding Sdn Bhd and Sime Darby Property hold 30% and the Pahang State Government holds the remaining 30%. The 49% stake of the Chinese consortium is held between the state-owned conglomerate Guangxi Beibu Gulf International Port Group (with a 95% equity interest) and Qinzhou Investment Company (the remaining 5% interest).

MCKIP is located in the East Coast Economic Region (ECER) in Malaysia. In 2008, the Malaysian government established the East Coast Economic Region Development Council (ECERDC) in order to spearhead the economic development of the East Coast. The five key economic sectors of the ECER are: (1) manufacturing, (2) oil, gas and petrochemicals, (3) tourism, (4) agriculture and (5) human capital development. The launch of MCKIP in 2013 has been one of the key milestones in the economic development of the East Coast.

MCKIP targets heavy industry and high-technology industry. These include energy saving and environment friendly technologies, alternative and renewable energy, high-end equipment manufacturing and the manufacture of advanced materials.