Chinese Mainland

By Paul Starr, King & Wood Mallesons

Paul Starr, Practice Leader Hong Kong Dispute Resolution and Infrastructure and James McKenzie, Senior Associate, King & Wood Mallesons, Hong Kong in conversation with Dr. Wang Wenying, Secretary General at China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission Hong Kong (CIETAC HK) and Sarah Grimmer, Secretary General at Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (HKIAC).

The Belt and Road initiative and Hong Kong

When you hear ‘Belt and Road’, what does that conjure up for your institution?

Wenying: While the Belt and Road initiative will directly or indirectly affect billions of people across the world and more than 60 countries along the routes, it will also create opportunities to build and grow Hong Kong’s role as a financier and dispute resolution hub for Belt and Road projects. This in turn will create opportunities for dispute resolution service providers in Hong Kong including CIETAC HK, which is usually the institution of choice for parties from China and Belt and Road countries to arbitrate considering its unique features.

Hong Kong plays a vital role in the initiative by bridging countries in the Asian region together. The establishment of CIETAC HK is itself a recognition by CIETAC of Hong Kong’s importance to the region. Many sectors in Hong Kong will consequently have a bigger role to play and will benefit from the initiative.

That’s true that Hong Kong is a bridge, in fact, the Hong Kong Government has referred to Hong Kong as a ‘super-connector’ for the Belt and Road initiative. What does HKIAC see as being particularly important to this connection?

Sarah: Hong Kong’s independent legal system and judiciary, extensive network of professional services in finance, accounting, construction and law, bilingualism, and geographical proximity to China are particularly important. A large proportion of the initiative's investment will be channelled through Hong Kong, particularly through Hong Kong incorporated vehicles. As a result, Hong Kong is a critical centre for Belt and Road projects.

In the legal industry alone, Hong Kong has over 1,000 barristers and 6,700 practicing lawyers. Hong Kong is one of the world’s top arbitration venues (voted the third most preferred venue in the world and first in Asia in a 2015 survey by Queen Mary University of London/White & Case survey). HKIAC, Hong Kong’s flagship institution, as well as other arbitral entities based in Hong Kong, and individuals providing legal and arbitration services, will need to think about how their services are relevant in the Belt and Road context and promote them.

In thinking about Hong Kong’s services, what would your institutions say to a Russian or African company that has previously only ever used the English arbitration system but is now involved with a Belt and Road project in which it is considering Hong Kong as a seat? What does Hong Kong have to offer?

Sarah: As many of the companies doing business on Belt and Road projects will be dealing with a Chinese counterparty, they should anticipate that the Chinese party may propose that the seat of the arbitration be in China and/or that the governing law is Chinese. Foreign parties should take advice on what it means for an arbitration to be seated in mainland China and/or on the particularities of Chinese law. Foreign parties often prefer Hong Kong as a seat given its modern arbitration legislation and independent legal system and judiciary. Chinese parties are also equally comfortable with Hong Kong as a seat and thus it is a compelling compromise.

Companies familiar with the common law and the English arbitration system will find Hong Kong particularly attractive as a seat or governing law when negotiating their arbitration clauses because it is a common-law system largely influenced by English law. With its large pool of legal professionals, independent judiciary (including non-permanent judges from other common law jurisdictions on its highest court) and state-of-the-art arbitration legislation, Hong Kong is the go-to jurisdiction for parties looking to meet their Chinese counterparties half-way. Russian parties in particular are looking more and more to Asia for business and dispute resolution services due to sanctions in other jurisdictions, we receive regular enquiries from Russian entities about our services.

Wenying: Under the principal of One Country, Two Systems, Hong Kong, as a Special Administrative Region of China, is supported by the Central Government to maintain its stability, development and prosperity. On the other hand, Hong Kong, under the Basic Law, enjoys independent judicial power including the power of final adjudication. It also continues to be an independent and neutral seat of arbitration to resolve the disputes arising from projects and contracts related to the Belt and Road initiative.

Hong Kong is a common law jurisdiction and there are similarities between arbitration practices in Hong Kong and England & Wales. But Hong Kong is at the same time fully capable of embracing parties and practitioners of different legal and cultural backgrounds together to resolve a dispute. Hong Kong also provides great options for parties when choosing arbitrators because a large number of experienced arbitrators reside or work in Hong Kong.

Belt and Road and dispute resolution

Another layer to this, of course, is that many of the Belt and Road countries contain high levels of legal and political risk. What do you think are some of the advantages and disadvantages of arbitrating Belt and Road disputes versus other dispute resolution methods such as litigation?

Sarah: Submitting disputes to arbitration avoids the perils of litigating in jurisdictions where the rule of law is not applied or where the courts are not independent. Given that some of the Belt and Road projects are massive, and involve national interests, removing disputes from local court sphere is critical.

Also, one of the greatest advantages of arbitration is the enforceability of awards. Belt and Road disputes will involve Chinese parties which means that enforcement may take place in mainland China against Chinese assets. We know that HKIAC and Hong Kong based awards have a strong enforcement rate in the PRC by virtue of the 1999 Arrangement between Hong Kong and the PRC. Recent studies show that enforcement rates in the PRC are improving, particularly with the reporting up system whereby an award can only be refused enforcement with the endorsement of the Supreme People’s Court. Foreign parties can also take comfort in the fact that the Hong Kong courts have enforced awards against Chinese SOEs.

Wenying: I agree that Hong Kong awards have a very strong track record. As the PRC is a signatory to the New York Convention, awards made in Hong Kong can be enforced in more than 150 countries and places under the New York Convention. There is also some harmonisation of arbitration laws along the Belt and Road with more than half of the Belt and Road countries having adopted the UNICTRAL model law in their domestic arbitration laws.

The enforcement of Hong Kong seated awards in the PRC is well handled by the ‘Arrangements of the Supreme People’s Court on the Mutual Enforcement of Arbitral Awards Between the Mainland and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region’. As an example, just recently, on 13 December 2016, the Nanjing Intermediate People’s Court of Jiangsu Province enforced a CIETAC HK arbitral award in the PRC, which demonstrates the capability of the PRC courts to enforce Hong Kong awards issued by CIETAC HK.

That’s an encouraging development. How important for enforcement and the ability to seek interim relief is it that Belt and Road disputes are seated in ‘pro-arbitration’ jurisdictions such as Hong Kong?

Wenying: In the PRC arbitration law, for example, interim relief cannot be made by the arbitral tribunal. In Hong Kong, the Arbitration Ordinance provides not only for court based relief in support of arbitration but that the arbitral tribunal can grant interim measures to protect the parties’ urgent interest when needed.

Interim relief is very important because, firstly, it may assist with enforcing the award capable of being enforced at the end when the winning party gets the award so the award is not just on paper. Secondly, it may help to resolve disputes more efficiently since it may facilitate the disputants to discuss settlement. Hong Kong is a well-known pro-arbitration jurisdiction with all the usual advantages in seeking interim relief and enforcing an order on interim relief rendered by an arbitral tribunal.

Given the operational and credit risks associated with many of the Belt and Road countries, what do you perceive to be some of the key considerations for investors in structuring their investment vehicle or drafting dispute resolution clauses?

Sarah: Investors should opt for arbitration rather than the submission of disputes to local courts. Investors should ensure that arbitration clauses across multiple instruments relating to a particular project are compatible. Parties should use compatible model clauses and may consider adopting an umbrella dispute resolution clause that applies to all related contracts.

Another important dimension we are now advising our clients on is investment treaty rights. What consideration should be made of these potential rights when investors are structuring their Belt and Road investments?

Sarah: Investors and host States should know which bilateral and/or multilateral investment treaties apply to their investment and decide how to structure their investment in order to attract treaty protection. This should happen prior to a dispute arising. This will include an assessment of whether the provisions of other treaties can be accessed through the application of most-favoured nations clauses.

Investment treaties often contain dispute resolution clauses referring investor state disputes to arbitration under, inter alia, the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules. HKIAC has already hosted multiple investor-state arbitrations and has administered arbitrations under the UNCITRAL Rules since 1986 under its own separate procedural guidelines. Furthermore, HKIAC has a tribunal secretary service which is particularly useful in large, complex cases (which investor state arbitrations very often are). HKIAC also recently launched a “free hearing space” initiative, offering parties in an HKIAC-administered arbitration involving a State listed on the OECD list of development assistance (which 70% of Belt and Road jurisdictions are) access to HKIAC’s hearing facilities free of charge. For some parties, the cost savings on hearing facilities will be a factor towards them choosing HKIAC and Hong Kong.

Wenying: For protection under an investment treaty, the person or company making the investment must qualify as an ‘investor’. Most treaties define ‘investor’ as either a natural person or a company having the nationality of the home State. The definition may differ between each bilateral and multilateral investment treaty and investors should always check the exact requirements under the relevant treaty. Although the method used to determine whether a company or person is ‘foreign’ varies across investment treaties, the party seeking to utilise the investment treaty must demonstrate that it is a national of one of the countries that is signatory to the treaty.

Belt and Road and CIETAC HK / HKIAC

What is being done to encourage use of your centres in disputes involving the Belt and Road Initiative?

Sarah: In 2017 and beyond, HKIAC will be playing a very active role in the Belt and Road initiative. We are planning to visit many Belt and Road jurisdictions this year, with the aim of educating local contracting parties about the key issues they need to know when undertaking a Belt and Road project. For example, what does a party need to know when concluding a construction contract funded by a Chinese SOE? Or one that may also involve a Chinese entity contracted in production capacity? What does a party need to know when its project is funded by a Chinese finance institution, whether that be an infrastructure bank, private equity firm or sovereign wealth fund? These are some of the practical considerations that parties need to take into account when embarking on Belt and Road projects.

Because of the very nature of Belt and Road projects, the disputes that emanate from them will often involve multiple contracts as well as multiple parties, including public entities, private equity funds, and SOEs both from within and without Belt and Road jurisdictions. The deals are major infrastructure projects which may involve high-stake disputes with a significant political element.

The 2013 HKIAC Administered Arbitration Rules (the “Rules”) are designed to deal with multi-party and multi-contract scenarios, such as those arising in Belt and Road disputes – specifically, our Rules allow for consolidation, joinder and commencement of a single arbitration under multiple contracts, and default appointment options. Our Rules also contain provisions allowing for expedited proceedings, emergency arbitrator proceedings and a choice of method for determining the tribunal’s fees which can save costs. To assist tribunals in handling large disputes, HKIAC also offers a tribunal secretary service from among the members of our multilingual Secretariat. They have experience in both commercial and investment arbitration and can work in English and/or Mandarin.

HKIAC has recently released statistics on the average duration and costs of its proceedings which demonstrate that it leads among the other major international arbitral institutions on both of these heads. HKIAC also has a deep pool of qualified and bilingual English/Mandarin arbitrators from which parties and the institution can appoint.

Wenying: CIETAC HK currently uses the CIETAC Arbitration Rules 2015 to administer its cases. The Rules are a happy marriage between the Chinese and the international practice of arbitration, which perfectly suits the potential commercial disputes among companies from the Belt and Road initiative. We have witnessed a convergence of arbitration rules among different institutions as they have developed over the past few years. However, there can be some distinctive features in practice among institutions, for example, mediation, scrutiny of awards and case manager systems.

CIETAC HK has gained a reputation of maintaining a relatively more efficient arbitration. Its average time for rendering an award in 2015 was 115 days from the date the arbitrators are appointed. CIETAC will update its pool of arbitrators this May thereby enhancing its capacity in resolving Belt and Road disputes by increasing Belt and Road related arbitrators.

What role do you see your respective centres playing in providing hearing facilities?

Sarah: HKIAC offers modern hearing facilities in the heart of Hong Kong’s central business district. Its premises were voted the best in the world for location, value for money, helpfulness of staff and IT services in 2015 and 2016. Additionally, as I mentioned earlier, HKIAC offers free hearing space for proceedings administered by HKIAC where at least one party is a State listed on the OECD DAC List of ODA assistance.

Wenying: CIETAC has a great network around the globe which allows us to provide hearing facilities readily available in China and at a great number of jurisdictions. CIETAC HK has adequate hearing facilities and caters to cross-border hearings on a regular basis. CIETAC HK will move to the Legal Hub, a wonderful initiative by the Department of Justice, in two years, which is exciting news that we wish to share.

For the traditional commercial arbitration cases that CIETAC HK carries out, if we look at CIETAC’s Fee Schedule, we can easily draw the conclusion that CIETAC is one of the very few international arbitration institutions that puts no additional burden on the parties for hearing facility costs.

We have talked a bit about the role investors play in choice of seat and arbitral institution. Another important party are “funders”. What role do your institutions see funders as playing in choice of dispute resolution clauses and what are your centres doing in terms of outreach to funding bodies?

Sarah: Third party funders’ primary concern is making returns in proceedings either through an award or settlement agreement. Effective enforcement of an eventual award is therefore critical, and choosing experienced arbitrators and institutions with modern rules goes a long way towards ensuring a valid and enforceable award. We work closely with third party funders in terms of mutual involvement in events and educating users. We also formed a special taskforce to consult with the Hong Kong SAR government on legislative reform as it concerns third party funding in Hong Kong.

Wenying: Yes, absolutely, and we are spending a lot of time in China talking to those groups. We recognise that as the parties providing the funds they have a lot of say in what dispute resolution clauses go into contracts.

What is being done by your centres to liaise with these organisations and encourage the choice of your centres and Hong Kong as a seat?

Sarah: We promote our work to Chinese SOEs both in the PRC and in Hong Kong. For example, in the week before Christmas, we hosted three large delegations of Chinese SOEs and arbitral centres in Hong Kong. In the PRC, HKIAC staff often meet with contractors and funders to understand their positions in different transactions and to promote the use of HKIAC’s Rules and services. We have also implemented Belt and Road seminars in Hong Kong and held Belt and Road roadshows in relevant jurisdictions that are recipients of outbound Chinese investment.

Wenying: We will have tailor-made events for investors on commercial arbitration, intellectual property disputes, construction dispute etc., including but not limited to seminars, mock arbitrations and negotiation workshops. We also work with chambers of commerce, governments, and institutes of arbitrators to communicate with arbitration users along the Belt and Road countries on the possibility of arbitration in Hong Kong.

Given all the talk about funding, it seems germane to talk about the pending third party funding reforms to the Arbitration Ordinance. What do your centres think the effect of the reform will be on Belt and Road arbitrations?

Sarah: The legislative reforms will bring Hong Kong into line with other major jurisdictions in terms of third party funding being available in arbitration. This is a positive development and makes Hong Kong more attractive as an arbitral seat. Some parties (whether these are impecunious parties or sophisticated entities using third party funding as a means of capital and liquidity management) may not wish to fund their disputes in the classical way, so third party funding arrangements are an interesting alternative.

Wenying: The Hong Kong Government has a long-standing policy of promoting Hong Kong as a leading centre for international legal and dispute resolution services in the Asia Pacific region. In recent years, third party funding of arbitration has become increasingly common in various jurisdictions.

The pending amendments to the Arbitration Ordinance to allow third party funding in arbitration and mediation proceedings is good news for dispute resolution services in Hong Kong. Third party funding will provide more options for parties initiating their arbitration case. CIETAC HK, with the help of its Working Group Members, has drafted guidelines to assist parties and arbitrators to be informed when considering using funding in their arbitrations.

Finally, what do you both see as the future of CIETAC HK’s and HKIAC’s involvement in Belt and Road?

Wenying: Before the Belt and Road, CIETAC HK was already the choice for resolving China related cross border commercial disputes. With the increasing volume of investment and trade, CIETAC HK will play a crucial role to resolve disputes arising from both.

Sarah: In 2017 and beyond, the Belt and Road initiative will constitute a significant part of HKIAC’s outreach and capacity work. As I mentioned, HKIAC has designed a roadshow for Belt and Road jurisdictions and has held that in the Philippines. We will also visit Mongolia and other jurisdictions this year. We are excited about promoting Hong Kong for Belt and Road disputes.

Please click to read the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

In the face of fierce market competition and rising wages and raw materials costs, some enterprises on the Chinese mainland are considering relocating their production to regions offering lower costs. At the same time, a large number of enterprises are choosing to adopt the strategy of transformation and upgrading in a bid to increase competitiveness and meet challenges. PEAK Corporation in Nanhai district, Foshan city, Guangdong province, is actively upgrading its automated production equipment while formulating a strategic production layout plan in an effort to expand its market share.

Introducing Robots to Ease Technical Staff Shortage

Engaged in the R&D and manufacturing of car lifts/hydraulic equipment, PEAK mainly relies on technology and quality to win in the market. Following changes in the external environment, some mainland enterprises seek to lower cost by relocating their production activities. But in contrast, PEAK spares no effort in enhancing its R&D capability and introducing welding robots and other automated production equipment, such as modified computer numerical control (CNC) sawing machines, stamping presses and automated feeder equipment. By so doing, the company can alleviate the problem of technical staff shortage while strengthening its ability to manufacture high-tech and high quality products.

A spokesperson for PEAK told HKTDC Research: “Manufacturing car lifts is a capital-intensive and technology-intensive production activity. While only a small number of non-technical workers are needed, skilled technical staff of the “master” grade are required to carry out the welding and installation processes.

“As such, shifting production to low-cost regions overseas often cannot solve the problem of a shortage in technical staff. Also, the business operations in question have to rely on the support of upstream suppliers in providing raw materials including quality aluminium, iron and steel. The company not only uses the right machinery and production equipment but also has in place a sound quality control system to ensure that its products meet the stringent technical and quality requirements of the mainland and foreign markets.

“Some low-cost regions in Southeast Asia are in short supply of technical workers and their raw materials supply chain has yet to be developed. If the metal materials produced in China are used to support production in these regions, the cost of transportation involved is huge. So relocation just for the sake of taking advantage of the lower cost of non-technical labour in these regions is often not worth the while.

The spokesman added: “In view of the fact that Guangdong province has a well-developed supply chain system and good logistics supporting services, in order to ease the problem of shortage in technical staff, PEAK has started to introduce automated welding robots in recent years. It is also co-operating with colleges and technical institutes in training more technical staff capable of operating robots and automated production lines.”

Actually, PEAK has already invested in setting up production lines in the US, utilising automated equipment to produce and assemble car lifts and hydraulic products. The production lines are slated to begin operating in the second half of 2017. The products will be mainly sold to the markets in North America, South America and Europe. Apparently, this move has not been made to lower production cost but to save on tariffs levied on products (or raw materials) imported into the country. It also serves to provide better sales and after-sales services to local clients. In addition, the company can capitalise on the sound local logistics network to cut logistics costs and transportation time in supporting its sales activities in markets neighbouring the US.

PEAK was established in 1999. Today, the company boasts not only advanced production equipment and high technology, but also a strong team of management personnel. Its products include single-post, twin-post, four-post and scissors car lifts, which are designed and manufactured in accordance with the technical standards of the America National Standard Institute (ANSI) and/or European Union’s CE. These products reach the relevant quality control standards and are mainly exported to overseas markets. In 2016, the company’s sales amounted to around US$17 million.

(Remark: The above is among the case studies of a research project jointly undertaken by HKTDC Research and the Department of Commerce of Guangdong Province: Shift of Global Supply Chain and Guangdong-Hong Kong Industrial Development. Please refer to the research report of the aforementioned project for more details.)

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Globalisation has precipitated the integration of regional supply chains. Many companies engaged in manufacturing on the mainland have been actively accelerating the “going out” policy by shifting some of their manufacturing business to Southeast Asia and other regions to optimise their overall production layout and meet the challenge of rising production cost on the mainland. Sunny Tan, Executive Vice President of Luen Thai Holdings Limited, says companies need to consider a host of factors other than production cost, such as the trade measures imposed by foreign countries, the supply chain in the relocation destinations, and the demands of end users, before they can effectively upgrade their overall production and operational efficiency.

Preferential Trade Arrangements Affect Production Layout

Tan told HKTDC Research: “Labour and land supply will of course directly impact production cost, but preferential trade arrangements granted by foreign countries to some places of production may also be crucial for lowering the cost of export to overseas markets. For example, products such as apparel and handbags may incur double-digit import tariffs (actual tariff depends on product) when shipped to Europe and North America. However, if they are entitled to tariff reduction and exemption, the benefits may exceed the extent of cost cut.”

He cited the following example: “Thanks to the easing of the US generalised system of preferences (GSP), bags manufactured in beneficiary countries like Myanmar and Cambodia can now enjoy zero import tariff in the US market. In addition, these two countries are also entitled to export bags to the EU, Japan and China with zero duty under different GSP arrangements and free trade agreements. In order to seize the opportunities and enjoy the relevant preferential tax policies, Luen Thai is expanding its bag manufacturing business in the Philippines and Cambodia through developing new capacity and converting some apparel manufacturing facilities for bag production in recent years.”

Provision of Strategic Production Services

Hong Kong-listed Luen Thai is a leading consumer goods supply chain group. It specialises in casual and fashion apparel, sweaters and accessories such as fashion bags and backpacks and makes use of its competitive price, good quality, prompt response and other advantages to provide OEM and ODM services for famous international brands. Its business strategy is to establish regional production networks in China and countries like the Philippines, Cambodia, Vietnam and Indonesia to benefit from the production advantages of different places in the provision of strategic production services to clients.

Luen Thai started its apparel production business in Hong Kong in the 1980s and established a network of production facilities in cities like Dongguan, Panyu and Meizhou in Guangdong province. In the wake of rising production costs and labour shortages on the mainland, it has gradually relocated its production to Southeast Asia in the past decade to lower costs and to benefit from the tariff advantages of these countries.

Tan said: “Not all low-cost countries are suitable for the relocation of production facilities from the Chinese mainland. It all depends on individual companies and the actual circumstances. For example, some ‘Belt and Road’ countries are not popular destinations for foreign investment. Companies may not know the laws and regulations and the culture of these places and may not be familiar with the local labour situation and production support services.

“These will directly affect the feasibility of plans to make investment and set up factories in these places. Moreover, low cost may be due to the lack of supply chain/material support, poor transport infrastructure and logistics services. Some countries have a good supply of unskilled labour but lack skilled workers and technical expertise, which makes it difficult for them to take on high quality and high value-added production activities.”

Catering to the Business Development of International Clients

Tan continued: “In addition to production factors, clients’ needs are also of crucial importance. Internationally renowned brands are quick to respond to market changes. As global economic growth slows down, different brands have been making every effort to upgrade their product design, materials and quality to fight for consumers’ limited spending power. They are willing to keep the production of these products in China and other places of production where the supply chain is more mature in order to be able to respond more swiftly to fierce market competition.

“For products that are more standardised or have a longer life cycle, such as T shirts, underwear and sports sacs, clients may be more willing to trade higher production risks and a longer production cycle for lower cost by shifting production to more backward places of production where cost is lower, such as Bangladesh and Ethiopia.”

Luen Thai owes its success not just to its policy of effectively using the best that the Chinese mainland and other overseas production bases have to offer to satisfy the demands of different clients, but also to its efforts to actively work with the overall brand development strategy of clients. In particular, the less well-known brands are very concerned about their brand and corporate image and want their manufacturers to strictly fulfill their corporate social responsibilities. Luen Thai strictly abides by the laws and regulations of the places of production and ensures compliance with the corresponding labour and moral codes. It also adopts effective environmental protection measures in compliance with the requirements of its clients in order to achieve the objective of sustainable business development.

(Remark: The above is among the case studies of a research project jointly undertaken by HKTDC Research and the Department of Commerce of Guangdong Province: Shift of Global Supply Chain and Guangdong-Hong Kong Industrial Development. Please refer to the research report of the aforementioned project for more details.)

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Asia is a fast-growing region. Companies in this region and multi-nationals are adjusting their business strategies rapidly in response to the changing investment environment. Hong Kong-based Artesyn Technologies Asia-Pacific Limited is a company mainly engaged in the manufacturing of information technology products and power supplies. In recent years, it has stepped up the integration of its mainland manufacturing activities, including upgrading its production plants in Guangdong, reinforcing the R&D capability of its Shenzhen Design Centre, and shifting some of its spare parts manufacturing activities to the Philippines where production costs are lower. In future, Artesyn hopes to capitalise further on the cheap labour of Southeast Asian countries in the production of power supply components and parts for its production plants in Guangdong, and make better use of the advantages of different regions for precision planning of production in order to improve its service to its clients in the Asian, European and North American markets.

Upgrading Production in China

Johnny Cheung, Artesyn’s Managing Director (China Operations), points out that, despite their cost advantages, many Southeast Asian countries are hindered by simple production conditions and supply chain systems. In comparison, the Chinese mainland boasts mature electronic manufacturing clusters that supply all the necessary spare parts and production backup services, as well as having an ample supply of tech talent. These are capable of effectively providing comprehensive services to domestic clients as well as to downstream manufacturers in the region, in the areas of material supply, mould and die design and manufacturing, technical support and provision of solutions. China remains a major region for the company’s development in the near future.

Cheung told HKTDC Research: “Faced with rising production costs and labour shortage on the mainland, Artesyn relocated its production facilities in Shenzhen to Zhongshan to lower cost while actively using the nation’s technological resources to reinforce the R&D capability of its Shenzhen Design Centre. Artesyn has in fact further upgraded its facilities in Zhongshan. The introduction of automated equipment has greatly eased labour shortage and made it possible for us to engage in production involving a higher level of technology. We have also built a production line in Luoding in a remote part of western Guangdong to make use of the city’s ample labour supply and lower labour cost to expand our production capacity.”

In order to diversify the risk of over-concentrated production, Artesyn acquired production facilities in the Philippines through its parent company, Artesyn Embedded Technologies Inc. This undoubtedly provides the company with a solution to rising production costs on the mainland. According to Cheung, employees in the Philippines speak good English and can effectively communicate with management personnel from Hong Kong and various parts of the world. This plant has a relatively low employee turnover rate, and stable employment is favourable for the management of production and staff training. Convenient transportation between the Philippines and China and reasonable logistics costs have also made it possible for Artesyn Embedded Technologies to continuously expand its production capacity in that country in recent years. It can take advantage of the relatively low cost of production in this country to produce electronic parts and components for Artesyn’s production activities in Guangdong.

Precision Planning for Production

Cheung said: “The Philippines is still in a developing stage in terms of supply chain, production network and support services, even in the supply of tech talent. Thus, we mainly make use of its labour resources to produce labour-intensive power supply parts and components as well as power supply units for which demand is relatively steady.

“The company’s production lines in Zhongshan and Luoding mainly produce a wide range of high-tech end products with the backing of the mature supply chain in the Pearl River Delta region. Artesyn also strengthens its engineering design so that its products can use more standard parts and components for automated production. While cutting down on the employment of unskilled workers on the mainland, it makes greater use of the cheap labour of the Philippines to produce power supply parts and components and strives to better leverage the advantages of different regions for precision planning of production in order to provide downstream clients with more cost-effective products.”

Artesyn is a subsidiary of the Artesyn Embedded Technologies Inc. and is mainly responsible for the company’s manufacturing business in China. Artesyn Embedded Technologies is a global leader in the design and manufacture of highly-reliable power conversion and embedded computing solutions for a wide range of industries, including communications, computing, healthcare, military, aerospace and industrial automation. As one of the world’s largest companies for embedded power supply business, it supplies clients with standard AC-DC products and a wide range of DC-DC power conversion products. It has over 20,000 employees worldwide across 10 engineering centres of excellence, four world-class manufacturing facilities, and global sales and support offices.

(Remark: The above is among the case studies of a research project jointly undertaken by HKTDC Research and the Department of Commerce of Guangdong Province: Shift of Global Supply Chain and Guangdong-Hong Kong Industrial Development. Please refer to the research report of the aforementioned project for more details.)

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Max Bonnell and solicitors Ruimin Gao and Erin Eckhoff, King & Wood Mallesons

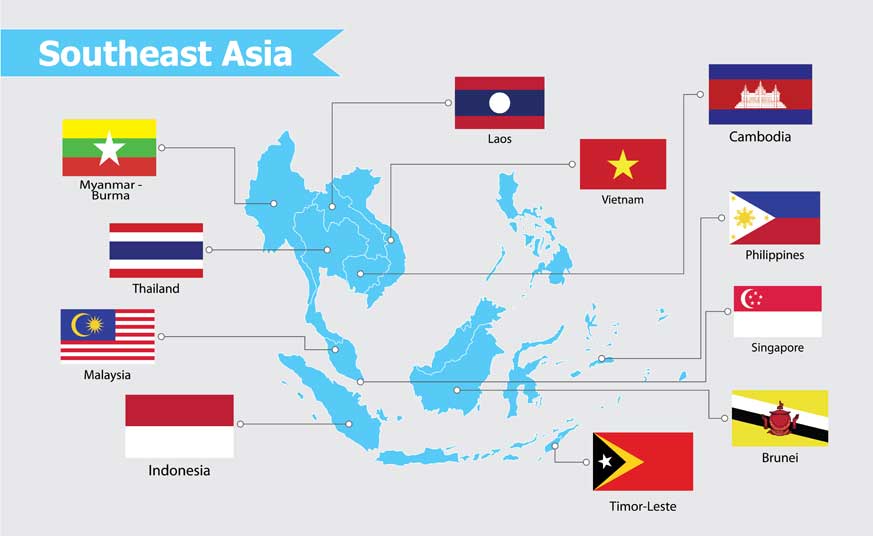

China’s Belt and Road Initiative is a visionary policy that aims to connect over 60 countries in Asia, Europe and Africa along five main routes of the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. Affecting a total population of some 4.4 billion (approximately 63% of the world’s population) and generating an aggregate GDP of over USD20 trillion (approximately 30% of global GDP), it is an ambitious framework that is projected to see significant numbers of infrastructure and other projects set up under its auspices. However, with such strikingly ambitious vision comes unchartered risks.

Since its announcement by President Xi Jinping in late 2013, over 600 contracts have been signed by Chinese enterprises for projects in countries along the Belt and Road routes. This number of cross-border contracts is set to continue to increase, especially as it has been projected that Asia alone needs about US8 trillion worth of basic infrastructure projects for the 2010 – 2020 period. Other than infrastructure and related projects, logistics and maritime sectors are also likely to see heightened activity in the Belt and Road regions.

The significant opportunities of the Belt and Road also come with significant risks of legal disputes arising. This is particularly the case given that the Belt and Road sees commercial contracts being concluded between parties from countries with very different legal systems and traditions. The uncertainty of financial exposure or other negative implications in the event of a dispute is a confronting spectre that threatens every cross-border transaction.

We discuss three key risks for cross-border commercial disputes and the ways to prevent and minimise exposure in order to fully benefit from the Belt and Road opportunities.

Risk #1: Unfamiliar courts and laws

It is an intimidating prospect for commercial parties to have a dispute litigated in a foreign court as it raises questions of real concern – what is the applicable law? Will the judges be impartial? Will the decision be recognised abroad? These risks are particularly relevant for commercial relationships that span multiple jurisdictions. International arbitration provides a number of benefits for parties wishing to resolve a cross-border dispute but seeking to avoid ending up in an unfamiliar court system, especially if any ensuing decision is of limited enforceability. Parties have the freedom to choose the applicable law to the dispute, the location of any hearing, the Tribunal members and even the language of the dispute. Making these choices at the outset of a commercial venture provides a very tangible degree of certainty to cross-border commercial endeavours.

When choosing where to arbitrate it is important to choose an arbitration-friendly jurisdiction, as it is the courts of the “seat” (i.e. the jurisdiction to which the arbitration procedure is tied) that will play a supervisory role in any dispute. This supportive role can include issuing subpoenas against witnesses or for the production of documents of third parties and granting emergency or injunctive relief. It is also the courts of the seat of the arbitration which will usually decide any appeal or setting aside proceedings. For Belt and Road investors, the region has a number of excellent jurisdictions for arbitration, including Singapore, Hong Kong and Sydney, which offer established arbitral institutions and common law traditions.

Risk #2: Uncertainty of outcome and impact to reputation

Another significant area of uncertainty for commercial parties concerns the outcome of the dispute – when will it be resolved and what will be the final ruling? In this context, international arbitration provides another benefit in that arbitral awards are binding on parties as soon as they are rendered and are final, subject to limited and mostly procedural grounds for the award to be set aside by a court. This relative certainty of an arbitral award is in contrast to a judgement rendered by a domestic court which is typically subject to multiple levels of appeal or judicial review with accompanying time and cost implications.

Another key area of uncertainty concerns the potentially negative implications of a dispute on the parties’ reputations. A reputable brand is of paramount importance to commercial parties that are dealing in transactions and trade. For this reason, parties commonly prefer for disputes and final rulings, particularly adverse findings, to remain confidential in order to avoid negative publicity. Litigation proceedings are generally conducted in open court and judgements are made publicly available. Arbitrations, on the other hand, are confidential and conducted in private, making arbitration often preferable in cases involving trade secrets or confidential commercial transactions, as well as for governments and state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

Risk #3: Enforcement challenges

Even once a commercial party is successful in a dispute, the risks do not end there. Enforcement of a judgement or award is the final but most important aspect of the dispute, as an inability to effectively enforce a judgement can render the entire preceding dispute process redundant.

One of the key benefits of international arbitration as a means of dispute resolution is that arbitral awards are enforceable in more than 150 countries that have signed the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Arbitral Awards (New York Convention). This offers a significant advantage over the enforcement of court judgements, which depends on the mutual recognition of judgements between States and typically requires legislation or another legal basis. Further, the process for enforcing foreign court judgements can differ significantly in different countries and can often pose difficulties for parties seeking enforcement.

When preparing commercial contracts, parties should opt for international arbitration if they want the option to enforce an arbitral award in one or more of the over 150 signatory countries to the New York Convention. In drafting the arbitration clause, though, parties must ensure that the seat of arbitration chosen is also a signatory to the New York Convention. This is because only arbitral awards made in a country which is a signatory to that convention can be enforced in another country which is a signatory to that convention.

The relative ease of enforcing arbitral awards globally is another reason why international arbitration is the ideal dispute resolution means for Belt and Road contracts. This has been recognised by the PRC Supreme People’s Court, which promulgated an Opinion in July 2015 stating that foreign arbitral awards relating to the Belt and Road should be promptly recognised in accordance with the law. The Supreme People’s Court also indicated strong support for use of international commercial and maritime arbitration for resolving cross-border disputes arising from the Belt and Road.

Lessons for businesses

Belt and Road is a ground-breaking initiative which will present significant opportunities as Chinese outbound investment in infrastructure reshapes international trade and relations. However, it is important to have the right tools to manage any accompanying risks in order to benefit from these opportunities. To this end, international arbitration provides commercial parties with mechanisms to mitigate risks, resolve disputes effectively and, ultimately, promote trade and commerce.

At its core, international arbitration upholds principles of due process and the rule of law whilst affording certainty and familiarity to parties who can tailor a dispute resolution process according to their own preferences and backgrounds. This is why, even though international arbitration cannot guarantee an ideal outcome for every dispute, it is unquestionably the best form of dispute resolution available when dealing with significantly different legal traditions and cultures, such as those along the Belt and Road routes.

Please click to read the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

With work beginning on the Bangkok-Nong Khai link, rapid pan-Asian rail connectivity looks set to become a reality.

A key element of the High Speed Rail (HSR) connectivity plan for Asia, an integral part of China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), was given the go-ahead early last month. This saw the Thai government formally authorise work to begin on phase one of the Bangkok-Nong Khai HSR project, an essential link in the overall network.

Back in 2016, work began on the much-delayed Kunming-Laos link, another key component of the wider network. More recently, Indonesia approved the Jakarta-Bandung HSR route. Meanwhile, the tender process for the 90-minute Singapore-Kuala Lumpur railway is set to commence in Singapore and Malaysia, with the project scheduled for completion by 2026.

In the case of the Bangkok-Nong Khai HSR link, this four-year, THB179 billion (US$5.3 billion) project will result in the creation of a 253km rail connection between Bangkok and Nakhon Ratchasima, the Thai city seen as the gateway to neighbouring Laos. In total, six stations will be constructed along the route – Bang Sue, Don Mueang, Ayutthaya, Saraburi, Pak Chong and Nakhon Ratchasima.

The line actually forms the first part of a three-stage project that will ultimately connect with Nong Khai and then Kaeng Khoi (Sara Buri)-Map Ta Phut (Rayong). At present, no schedule has been agreed for the completion of the final two phases.

Although phase one is primarily being financed from within Thailand, the Thai government is reportedly in negotiations with the Export-Import Bank of China with regard to financing the required high-speed rolling stock. The overall plan is for Thai firms to build the track, while China will supply the trains and signal systems, and provide technical support.

The long-term objective is to establish a trans-Asia high-speed rail link capable of delivering a journey time of just four hours between Bangkok and Vientiane, the Lao capital. Beyond Laos, the proposed link would then extend to Kunming in southwest China, feeding into the mainland's rapidly expanding inter-city HSR network, which had about 22,000km of track as of the end of 2016. Heading south from Bangkok, the high-speed link would also significantly reduce journey times to Kuala Lumpur and Singapore.

Although the negotiations and many of the approval processes have proved to be slow and have faced frequent delays, Thailand remains committed to the proposed high-speed link, seeing it as set to play a key role in its own future economic growth. In the first quarter of 2017, boosted by recovering export levels, the Thai economy expanded by 3.3%, its fastest quarterly growth for four years. Despite this recent rally, the country's economic growth has been trailing its regional peers since 2014.

In 2016, the Thai economy grew 3.2%, with the Asian Development Bank predicting a 3.5% increase for 2017, rising to 3.6% in 2018. Although representing something of an uptick, these figures are still below the projected ASEAN average and remain significantly down on the 7.2% growth the country recorded back in 2012.

The advantages offered by the country's geographic location are central to its hopes of a sustained economic upturn. Set at the heart of continental Southeast Asia, Thailand shares borders with Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia and Malaysia, with the latter sharing a land border with Singapore, home to the world's second-busiest port. With a population of about 69 million and highly developed logistics and finance resources, Thailand is also seen as perfectly positioned to capitalise on the benefits of the free movement of people, products and capital guaranteed under the constitution of the ASEAN Economic Community.

It is also hoped that enhanced rail connectivity will boost tourism, which currently accounts for about 11% of Thai GDP. The country has already committed itself to becoming “the tourism hub of Southeast Asia” and has made considerable progress in terms of delivering on that. In 2016, for instance, it welcomed 32.6 million visitors, generating THB1.64 trillion in revenue. It is now looking to attract ever-increasing numbers of high-spending visitors from China, India and from throughout the ASEAN bloc.

At present, the Tourism Authority of Thailand is strongly promoting the country as a holiday destination in many of the mainland's second-tier and third-tier cities, having identified them as China's primary source of next generation tourists. Last year, about 8.8 million Chinese tourists visited Thailand, while the ASEAN bloc accounted for further 8.6 million visitors. Although the total number of tourists was up for the first half of 2017 year-on-year, the level of mainland visitors dropped by 3.83%.

This was largely seen as the consequence of a crackdown on so-called 'zero-dollar' trips – cheap packages offered to Chinese group travellers who are then pressured into spending at high-priced shopping and dining outlets by commission-only tour agents. Despite the disappointing figures, however, China remains – by a considerable margin – Thailand's number-one tourism source, followed by Malaysia, South Korea and Laos.

With the country's commitment to the pan-Asian HSR project now confirmed, its position as the connective hub for Southeast Asia's emerging high-speed rail links brings the transformation of rail transport across the continent one step closer. That promises to be good news for the wider tourist industry, as well as for exporters and importers across the region.

Geoff de Freitas, Special Correspondent, Bangkok

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Nadège Rolland, National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR)

China’s Grand Strategy - The BRI is now one of the main instruments of China’s grand strategy.

In sum, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is an essential component in China’s larger effort to solve the fundamental geopolitical challenge that it faces, something its strategic thinkers have been considering since at least the turn of the 21st Century: how can China “rise”—assert its influence and reshape at least its own neighborhood — in ways that reduce the risk of a countervailing response? The Belt and Road Initiative attempts to combine all of the elements of Chinese power and to use all the nation’s strengths and advantages in order to achieve these ends. China’s banks, SOEs, diplomats, security specialists, intellectuals, and media have all been summoned to join in this effort. In other words, the BRI is now one of the main instruments of China’s grand strategy, coordinating and giving direction to an extensive array of national resources in pursuit of an overarching political objective. Focusing only on specific components or dimensions of the BRI, as most Western studies currently do, risks missing the point that all of these aspects are part of a comprehensive vision with a potentially global reach. To those who feel “underwhelmed” by its concrete achievements to date, it is important to keep in mind that the BRI goes well beyond the simple pursuit of economic gain through a series of ambitious engineering projects. It is intended to take a large step toward the realization of the “China Dream,” restoring the nation to its rightful place as the paramount power in Asia in time for the PRC’s 100th anniversary in 2049.

It remains to be seen how far the Belt and Road can go. If it unfolds as Beijing envisions, the implications would certainly be far reaching: an integrated and interconnected Eurasian continent with enduring authoritarian political systems, where China’s influence has grown to the point it has muted any opposition and gained acquiescence and deference; a new regional order with its own political and economic institutions, whose rules and norms reflect China’s values and serve its interests; and a continental stronghold insulated to some degree from American sea power.

Of course there are many obstacles along the way, as China’s leaders are well aware. Some of these can no doubt be overcome, but the BRI will also produce effects that are unexpected and unintended. The tremendous effort and massive resources China has committed to the Belt and Road should at a minimum generate greater international Western attention to its development, underlying motives, and possible strategic implications. This is an endeavor that the Chinese leadership takes very seriously. Others should do the same.

Please click to read the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Amitai Etzioni, International Relations at the George Washington University

The Silk Road is again in the headlines. Some thirty world leaders recently participated in the inaugural Belt and Road Forum (BRF) in Beijing, to consider Chinese President Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy initiative. Sixty-eight countries have already signed agreements with China to participate in the initiative, in which China is said to invest nearly one trillion dollars. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has been dubbed “the project of the century.”

The recurrent publicity about the project raises the hackles of American officials who see it as geopolitics by others means. Trump’s Director of National Intelligence, Dan Coats, said in a recent testimony before the U.S. Senate that the Belt and Road Initiative fits within a pattern of “aggressive” Chinese investments. Coats added that the purpose behind the initiative is for China to “expand their strategic influence and economic role across Asia through infrastructure projects.” Franklin Allen, a professor of finance and economics at Imperial College in London believes that “it is an economic initiative, but along the way China will expand its military bases and so forth.” The Economist sees the Belt and Road Initiative as an attempt by China to replace the U.S. as the leader of global trade.

A less alarmed view finds first of all that the whole project is much overhyped. Figures about investments include projects that had been previously launched. Several projects, including some in Myanmar and Pakistan, have already gone belly up, causing Chinese investors to lose major parts of their investment. Moreover, as the U.S. discovered when it provided aid or invested in other nations, such measures often buy resentment rather than influence. And if China does contribute to the development of infrastructure in Central Asia, and thus to the development of this part of the world, this may well benefit the people of the region and help the nations involved achieve some stability.

In determining how to react to the Silk Road initiative, the West should draw on a major strategic consideration: Do the U.S. and its allies plan to block any and all increases in Chinese influence—or merely contain those moves that entails China’s use of force to dominate other countries?

The important underlying assumption is that a rising China is akin to a rising wave of energy; a strategy that allows that energy to be expended in ways that will not harm the international order and may indeed benefit it is more likely to succeed than one that seeks to bottle up that energy by seeking to block it everywhere. Implementing this strategy thus entails accommodating China’s desire to have more influence, but preventing coercion.

It is important to also distinguish between influence and coercion. Although China is likely to increase its influence in the region, its growing influence should not be equated with aggression. Influence leaves the final decision on how to act in a given scenario to the actor being subjected to the influence. Coercion, on the other hand, preempts such choices and forces those subject to it to abide by the preferences of the actor wielding force. For example, Germany has a disproportionate measure of influence over most European affairs relative to other EU member states, but this does not make it an aggressor, much less a regional hegemon. While in the past, the U.S. was a hegemon within the Western Hemisphere that coerced states that did not abide by its directives, and although it still has more influence in most of the region than any other power, it is no longer aggressive nor a hegemon. So according to the only aggression denying strategy, the U.S. and its allies should not tolerate the coercive use of force in the region (which would violate the long-standing Westphalian principal of sovereignty). However, when China’s moves are limited to seeking to increase its regional influence—say through public diplomacy, trade, investment or cultural exchanges and by investing heavily in the Silk Road—the U.S. should counter such influence with the same kind of means but not by military buildup and implicit threats to use it. This strategy seems preferable to both seeking to maintain the status quo (which leaves little, if any, room for a rising China to expend its rising energies) and retrenchment (in which the U.S. withdraws from Asia under some kind of America First strategy).

The preceding analysis assumes a clear distinction between being a hegemon and an influential power. Dictionary definitions of hegemony conflate influence with dominance. Hegemony might be best defined as the ability of a nation to preempt another nation (within whatever sphere it exerts hegemony) making decisions opposed by the hegemon. In contrast, an influential nation is merely able to get the other nation or nations to grant extra weight to its preferences compared to its own preferences or those of other nations. Distinguishing between these terms highlights important differences between strategies that seek to prevent China from becoming a dominant power and those that also seek to deny it increased influence.

All this means that the U.S. has no reason to oppose China’s major investments in infrastructure drive, one that will help finance the building of roads, railways, ports, bridges and pipelines. And if as a byproduct China will gain some additional influence in Asia (which does not necessarily follow) there is no cause for alarm. For instance, since the U.S. tilted toward India under the Bush administration, China gained somewhat more influence in Pakistan, but this increase did little to change the basic geopolitics of the region.

True, in a case of war, a developed Silk Road may make blocking China—which various U.S. military planners call for, as a less aggressive approach than invading the mainland—more difficult. However, allowing China to gain economic influence but not military dominance, and securing a much needed pathway for its much needed resources, will make war less likely.

Please click to read the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

The industrial landscape in Asia is undergoing a fresh round of changes. Following the earlier large-scale relocation of production activities from many of the developed countries to lower cost regions in the late 1990s, industrial production activities soared across Asia, particularly in China, which emerged as a manufacturing power house. In recent years, however, the investment environment in China has begun to change. Rising labour and production costs across the mainland have prompted a number of foreign-invested and domestic enterprises to adjust their business strategies, frequently resulting in the relocation of part of their production activities to other locations within Asia, while their mainland business operations have been upgraded in a bid to enhance their competitiveness.

The Changing Business Strategies of Guangdong and Hong Kong Enterprises

Many of the local and Hong Kong enterprises engaged in production and trade in Guangdong actually began to adjust their strategies several years ago in order to cope with the changing investment environment of the Pearl River Delta (PRD) region. Among the steps taken was the relocation of a number of production and sourcing activities to lower-cost regions on the mainland.

Quite a number of these businesses also opted to set up production facilities in one of the Southeast Asian and other countries set along the Belt and Road routes or to source various products and raw materials from such locations in the hope of reducing costs through the utilisation of external resources. As the growth of both the global and mainland markets has slackened over recent years, amid intensified competition from other low-cost regions, as well as controlling costs, many Guangdong and Hong Kong enterprises have had to take further action with regard to their transformation and upgrading. This has seen many of them aim to switch from labour-intensive production to high value-added business in order to secure sustainable development in the medium to long term.

Many such enterprises have invested heavily in automation in order to alleviate the problem of labour shortages. By using automated production lines, they also hope to produce items of a higher quality with a greater degree of precision in order to meet the increasingly stringent requirements of the international market and to compete more effectively. While some enterprises have increased investment in technological research and development in an effort to develop into a more high-tech business, others have chosen to build their own brands to raise the perceived value of their products. As the pace of globalisation has quickened, the division of labour between different industrial sectors has become increasingly well-defined, a development that has, in turn, made the management of the global supply chain ever more complicated. In this regard, many enterprises in Guangdong and Hong Kong have had to adjust their strategies in light of the changing external environment in order to achieve a more comprehensive transformation and upgrade.

The Developing China/Asia Supply Chain

The advanced supply chain system and range of production support services enjoyed by the PRD is, arguably, unmatched anywhere else in world. In view of this, when mapping out future business plans, the majority of Guangdong and Hong Kong enterprises have opted to retain and even expand their production activities in the PRD, Guangdong its neighbouring regions, often prioritising higher value-added and higher technology content. At the same time, as industrial activities in other low-cost regions across Asia have continued to thrive, the supply chain relationship between China and Asia (including the ASEAN countries) has become increasingly close, a development that, in turn, offers an expanded market and wider sourcing options for Guangdong and Hong Kong enterprises.

At present, many enterprises ship large quantities of industrial materials from the PRD and other mainland regions to Asia and to other countries along the routes of the Belt and Road in order to support local industrial production activities. A number of such enterprises have also relocated to one of these low-cost regions in a bid to enhance their sourcing activities. Typically, the end-products produced/sourced in these regions are then sold on to the more developed countries, while the industrial materials, parts and components sourced there are shipped back to the PRD and other mainland regions in order to support higher-end production activities. Across Asia, the division of labour has become more and more well-defined, while the trading relationships between upstream/downstream suppliers and manufacturers in China and in a number of different Asian regions has become closer and closer. This has, in turn, fuelled the rapid expansion of intra-Asia trade.

Optimising Regional Business Plans

Generally speaking, in many of Asia’s lower cost regions, production conditions are somewhat basic, while the logistics and support services still have much room for improvement and technical personnel remain in short supply. As such, the enterprises that have relocated their production lines to these regions tend to be mainly confined to low-end, labour-intensive processes, producing light industrial goods as well as parts and components with a longer life cycle. Apart from labour costs, enterprises shifting their production offshore must also take into account their overall costs, including transportation, logistics, materials supply and management.

Coupled with the longer turnaround time required for such cross-regional arrangements, this requires the establishment of a highly efficient supply chain management system if industry players are to capitalise on the opportunities arising from changes to the international market. In light of this, when any such enterprise seeks to map out its offshore production plans, it is advised to take into consideration a number of factors, most notably whether the proposed production activity is compatible with the resources of the local market. As additional considerations, the trade barriers and preferential tariff policies implemented by the EU, US and other export markets may also impact on the regional production and sourcing plans of many enterprises.

Overall, as competition in the international market intensifies and the global supply chain continues to evolve, Guangdong and Hong Kong enterprises can no longer solely rely on their facility to lower direct production costs as a way of remaining competitive. Instead, they will have to proactively adopt a number of alternative strategies, including transformation, upgrading and enhancing business value. They will also need to take into consideration such concerns as overall market demand and cost benefits, while looking to optimise their regional business plans in order to increase their competitive edge.

Against this backdrop, Guangdong and Hong Kong should strengthen co-operation when it comes to formulating the necessary policies for promoting the further development of commercial entities in both locations. In particular, every effort will need to be made with regard to the application of smart manufacturing technology as a means of pursuing industrial upgrading, while action should also be taken to promote technological co-operation between enterprises in both locales and to accelerate the pace at which technological achievements are commercialised. Furthermore, both Guangdong and Hong Kong should look to improve the transport and logistics networks that connect them in order to ensure their respective enterprises can effectively plan for business development across the region. Steps should also be taken to encourage all such enterprises to work together when “going out” to capitalise on any emerging Belt and Road opportunities. They should also look to make best use of Hong Kong’s professional services sector in order to formulate long-term developmental strategies and to effectively manage risk. All the while, they need to strengthen their connections with Asia’s growing regional supply chain and make better use of the various regional resources available in order to expand both the mainland market and the wider export opportunities.

Please click here to purchase the full research report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By David Dollar, John L. Thornton China Center, Brookings Institution

For the five-year period between 2015 and 2019, China’s President Xi Jinping set an ambitious goal of $500 billion in trade with the Latin American and Caribbean region (LAC) and $250 billion of direct investment. The pledge was made at the first ministerial meeting of the Forum of China and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, held in Beijing in January 2015. China has set some large investment targets in Southeast Asia and Africa that it has not always met, so it remains to be seen if this degree of integration can be achieved. But the investment numbers are certainly plausible, as China is likely to emerge in the next few years as the world’s largest supplier of capital.

The outflow of capital from China takes two main forms. These are direct investment, which consists of greenfield investments plus mergers and acquisitions, and lending by China’s policy banks, which are the Export-Import Bank of China (China EXIM Bank) and China Development Bank (CDB). China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) reports the allocation of China’s overseas direct investment (ODI) among recipient countries. Specifically, MOFCOM reports the annual flow of ODI and the accumulating stock of China’s outward investment. In recent years, China’s ODI has amounted to somewhat more than $100 billion per year, accelerating to above $200 billion in 2014. The cumulative stock tripled between 2010 and the end of 2014, reaching nearly $900 billion. Of this total, $106 billion was direct investment to Latin American and Caribbean countries.

One problem with China’s reporting of the ODI to individual economies is that about half of China’s global ODI goes to Hong Kong. And within Latin America and the Caribbean, large amounts of China’s ODI go to the Virgin Islands and the Cayman Islands. These money centers are certainly not the ultimate destination for all of this investment. China should work to improve its statistics to reflect the ultimate destination of its overseas investments so that publics everywhere have more-accurate information. In general, direct investment is welcome, so it would be in China’s interest to produce better data that more accurately reflects its growing role in global investment.

How is Chinese investment likely to evolve?

To the extent that Chinese investment differs from global norms and practices, there are three possible paths forward: (1) Chinese investment could become more typical; (2) global practices could shift in the direction of China; or (3) China could remain at odds. This section speculates that in Latin America we are likely to see some combination of all three possible outcomes.

First, when it comes to investment in poor-governance environments, China is likely to evolve in the direction of current investment norms—that is, to favor better governance environments. Part of China’s motivation for investing in countries such as Venezuela and Ecuador was to gain access to natural resources. In the 2000s, China’s growth model was highly resource-intensive and global prices for most commodities were rising. That made it tempting to look for resources even in risky environments. That has all changed this decade, however. A lot of new supply has come online in sectors such as oil and gas, iron, and copper. Meanwhile, China’s growth model is shifting away from resource-intensive investment towards more reliance on consumption.20 Consumption primarily consists of services, which are less resource-intensive. As a result of these shifts in supply and demand, commodity prices have come down, and China’s import needs have diminished.

Also, as noted earlier, the investments in poor governance countries are not working out well. A study concludes that the relatively strong Chinese involvement in poor-governance states such as Venezuela represents “Beijing filling the ‘void’ left by a declining American presence in Washington’s own ‘backyard.’” The fact that China has stopped funding Venezuela suggests, instead, that it has a more practical and economic attitude to these countries. As Chinese people demand a better return on state-backed investments abroad, it is likely that China will pull back on the resource investments in countries with poor governance. At the same time, many Chinese private firms are looking to invest abroad in a wide range of sectors, and those investments are heading to the United States, other advanced economies, and emerging markets with relatively good governance, as is the case with global investment in general. How much of a concern should this be for the United States? In a companion paper to this one, Harold Trinkunas finds that “the scope for Chinese leverage on Latin American governments is limited to a small set of countries.” Ted Piccone analogously concludes that “for now… China’s rise has generally not impinged on core U.S. national security interests but requires careful monitoring.” My finding of rather indiscriminate investment by China across the continent is consistent with these more benign assessments of China’s activity in Latin America and its potential to generate U.S.-China conflict.

Concerning environmental and social safeguards for infrastructure projects, China has identified an issue that resonates with other developing countries. The World Bank and other multilateral development banks have been imposing environmental and social standards that reflect the preferences of rich-country electorates. Developing countries have been voting with their feet and have turned away from those banks as important sources of infrastructure financing. In general, they welcome Chinese financing of infrastructure. The response among developing countries to China’s proposal for a new infrastructure bank, AIIB, was especially strong. Asian countries that are not particular friends of China, such as India, Indonesia, and Vietnam, were quick to sign up for the effort. AIIB’s attempt to develop workable safeguards to address environmental and social risks without the long delays and high costs of practices at existing multilateral development banks is an important innovation. Latin American countries have indicated their preference by borrowing more from Chinese banks for infrastructure than from the World Bank and IADB. The Chinese-financed projects, however, do carry significant environmental and social risks and it will take strong oversight from Latin American governments and civil society to ensure that benefits exceed costs. Environmental and social safeguards are examples of areas where China may end up modifying global norms to make them align better with developing country preferences.

The third issue identified in this essay, reciprocity, should be an easy one for China to address. There is ample evidence that big state enterprises are less productive than private firms in China. Many of the sectors that remain closed in China are service sectors such as finance, telecommunications, transportation, and media—all of which are dominated by large state enterprises. With the shift in China’s growth model, these service sectors have now become the fast-growing part of the economy, while industry is in relative decline. It will be easier for China to maintain a healthy growth rate if it opens these sectors to international competition, in the same way that it opened manufacturing in an earlier era. And talk of opening these sectors can be found throughout party documents, such as the recent Third Plenum resolution. However, actual progress with opening up under the new leadership has been slow. It may be difficult for China to commit to any bold opening up in the next few years as it grapples with adjustment of its growth model and as it prepares for a political transition in 2017. It is likely that China will remain more closed to inward investment than its partners, which creates a dilemma for them. However, Latin American governments will probably continue to welcome Chinese investment despite the lack of reciprocity.

Please click to read the full report.