Chinese Mainland

By Le Xia, Chief Asia Economist, BBVA

Mainland China’s outbound foreign direct investment (ODI) saw a big turnaround as its strong growth momentum in 2016 – which reached 49.3% for non-financial ODI flows – came to a halt last year. This is mainly due to the authorities’ restrictive measures to curb capital outflows. In particular, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) formalized the regulatory pathway for ODI transaction approval in August 2017 to classify outbound investment into three groups: encouraged, restricted and prohibited transactions.

The encouraged group includes the areas which are important to the country’s growth and development such as infrastructure projects related to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), high-tech business, advanced manufacturing, and research and development. Meanwhile, the restricted group includes deals related to real estate, sports clubs, hotels, entertainment and the film industry. Moreover, overseas investment in gambling or sex industries is strictly prohibited.

These tightening measures have proved to be effective. Since August 2017 there have been no recorded Chinese acquisitions in property, sport and entertainment. Meanwhile, the share of ODI in the commodity and energy sectors started to rise. Investment in these sectors accounted for 49.4% of total ODI flow in 2017, way above 29% in 2016.

Although the decline of ODI is broad-based, the government has continued to stress its determination to press ahead with its new national BRI strategy, with the Mainland’s ODI flow to the 65 BRI countries remaining broadly flat in 2016 and 2017. Accordingly, the share of investment to BRI countries increased to 12% of total ODI from 8% in 2016.

The authorities’ newly selective stance on overseas investment has led state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to outperform their private peers, as many of the former’s overseas investment projects are tied to the government’s favoured BRI strategy. Moreover, their dominance in international construction projects can give them more opportunities to make investments related to construction.

However, the ODI of Chinese SOEs may be substantially aided by concessionary financing from state controlled banks, which has increasingly caused foreign concerns over the fairness of the playing field.

Looking ahead, a number of tailwinds and headwinds have emerged to shape the pattern of Mainland China’s ODI going forward.

Encouragingly, many foreign countries’ views towards overseas investment have somewhat improved over the past two years despite the rise in populism around the globe. Our research has found that the evolution of media sentiment regarding Chinese investment in infrastructure improved in most countries in 2017 compared to 2015.

Adding to the tailwinds are some government-led initiatives. Under the BRI, China created a US$40 billion Silk Road Fund to boost infrastructure investment. Additionally, Beijing spearheaded the creation of the US$50 billion Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the US$50 billion BRICS New Development Bank.

In 2015, the country also set up two funds earmarked for its cooperation with Latin America – the China LAC Industrial Cooperation Investment Fund and the China-Latin America Infrastructure Fund. ODI flows to these regions will be greatly aided by improved economic integration and financing for infrastructure investments. Latin America is another region that is bound to receive more ODI on the back of new bilateral lending and investment deals.

However, headwinds to Mainland China’s ODI exist not only at home but also abroad. Anti-globalization movements have intensified in recent years and the international environment has become increasingly uncertain.

The United States has expressed increasing concern about Chinese attempts to acquire technology. The European Union has unveiled proposals of a new framework to screen foreign investments to avoid hostile takeovers in some sensitive sectors; this idea was pushed by France and supported by Germany and Italy. More recently, Australia said it plans to tighten rules on foreign investment in electricity infrastructure and agricultural land, amid concerns about growing Chinese influence in business, politics and society.

In the future, despite the uncertain global environment, outbound investment by Chinese firms is likely to rise over the long term, due to the authorities’ efforts to boost BRI projects and its support of overseas acquisitions that allow Chinese firms to acquire advanced technology and strategic assets.

Continued growing investment and trade links between Mainland China and BRI countries are expected amid connectivity improvements in the next few years. The country’s various industrial sectors will benefit via government-backed entities and, to a lesser degree, multilateral entities. These government-led initiatives will help to improve economic integration and expand the market for Chinese goods and services overseas, all of which will open opportunities for Chinese companies abroad.

Supported by discount financing, immediate beneficiaries will be seen in sectors such as engineering and construction, survey and design, railway signalling systems and rolling stock, as well as in steel machinery and aerospace and defence exports. Over time, we expect operators of ports, railways and other infrastructure to gain from higher volumes initiated by increased bilateral trade between Mainland China and BRI countries. Moreover, mining, transportation infrastructure, manufacturing and information transmission sectors will also benefit.

The industry growth driver for the Mainland’s ODI will move from the property market, hotels, and entertainment to the infrastructure sector, and SOEs will still dominate. Government support for initiatives such as BRI and AIIB will not only fuel infrastructure-related sectors, but also boost bilateral trade over the medium term, with upgraded interconnectivity. These initiatives may also promote increased RMB usage in funding for infrastructure projects and trade deals.

This article was first published in the magazine The Bulletin April 2018 issue. Please click to read the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Although officially cynical as to the aims of the BRI, India is a major recipient of related infrastructure funding.

While some have expressed surprise that Mumbai was the setting for last month's third annual meeting of the Beijing-headquartered Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the choice was wholly in keeping with both the body's long-term agenda and its more recent track record. For more than a year now, India – despite its public protestations of concern over the apparent political intent behind the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – has been partnering with China in order to fund a number of its infrastructure projects, with the AIIB the primary investment vehicle.

It is also worth remembering that, after China, India is the AIIB's second-largest shareholder, as well as, of late, one of its key beneficiaries. Of the US$5.3billion in loans signed off by the AIIB, nearly a quarter of that sum – around $1.3 billion – has been allocated to India-based projects.

Opening proceedings on 25 June, Jin Liqun, the former banker and academic who now serves as the AIIB's President, made clear the links between the institution and the BRI programme, saying: "In addition to our formal partnerships, our members are involved in a wide range of regional infrastructure and trade arrangements, with the BRI being a prime example."

He later amplified his comments at the 2 July Forum on Belt and Road Legal Cooperation. Addressing delegates at the Beijing-hosted event, he said: "To my mind, all AIIB-backed projects are connected with the Belt and Road Initiative."

Of the 28 projects so far approved by the AIIB, seven are located in India, with a further five such initiatives in the pipeline. Among those already in place are two India-specific infrastructure funds and five developments seen as hugely BRI-friendly.

Of the funds, the National Investment and Infrastructure Fund Phase I – as approved on 24 June this year – is a $700 million undertaking co-financed with the Indian Government. Overall, the AIIB has put up $100 million as a means of addressing the equity funding gap that is currently bedeviling a number of Indian infrastructure projects. The other fund, the North Haven India Infrastructure Fund, is a private equity fund, overseen by Morgan Stanley, with a remit of raising between $750 million and $1 billion, with the AIIB committed to putting in up to $150 million.

The most recent initiative to secure AIIB approval is the Madhya Pradesh Rural Connectivity Project, a $502 million upgrade to the road network in Madhya Pradesh, India's second largest state and one of its poorest. The project will enhance the connectivity of 1.5 million people living in 5,640 villages throughout the state, while giving them improved access to education, health and retail facilities.

A major undertaking, the project will require the surface-sealing of 10,000km of existing roads and the construction of 510km of wholly new roads. The project will also put in place the civic support structures required to manage and maintain this upgraded road network. In order to deliver on this, the AIIB has agreed to provide $140 million of funding, with the World Bank putting in an additional $210 million and the Indian Government making up the balance.

The AIIB has also signed-off on $329 million in funding for the Gujarat Rural Roads (PMGSY) Project, an initiative it is co-funding with the Government of Gujarat. A further two projects have seen AIIB funding earmarked for upgrading India's electricity transmission facilities. This has seen the bank agree to provide $160 million of funding for the Andhra Pradesh 24x7 Power For All Project. Co-financed with the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the Government of Andhra Pradesh, this will facilitate a major upgrade for the state's electricity transmission network.

The AIIB is also to commit $100 million to a Transmission System Strengthening Project in Tamil Nadu, India's 11th largest state. This initiative is to be co-financed with the Asian Development Bank and India's Power Grid Corporation.

The final project – the AIIB's largest undertaking in India – is Line Six of the Bangalore Metro Rail Project. With the bank committed to providing $335 million of the estimated overall $1.785 billion cost, the project will involve a 22km extension to the city's existing metro system and the construction of 18 new stations. The co-financers in this particular project are the European Investment Bank and the Indian Government.

Geoff de Freitas, Special Correspondent, Mumbai

Editor's picks

Trending articles

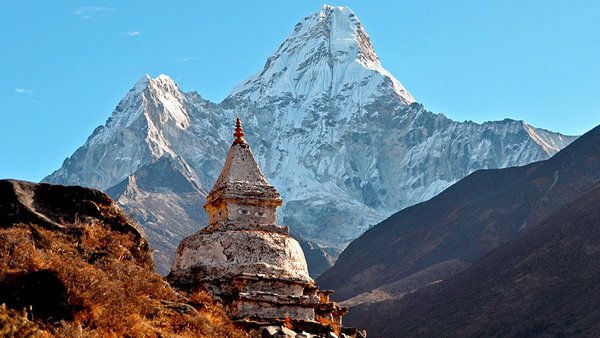

Having signed 14 BRI-related MoUs with China, Nepal must work harder than ever to keep India genuinely neighbourly…

Last month's five-day visit to Beijing on the part of Khadga Prasad Sharma Oli, the recently-elected Prime Minister of Nepal, seems to have opened the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) floodgates, with 14 related projects having now been given the go-ahead by the Himalayan kingdom, while several existing hydro-electric developments have been galvanised back into life. Backed by a series of Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs), the new projects are largely geared towards boosting cross-border connectivity between the two neighbouring nations.

In a statement released in the immediate aftermath of the visit, both countries agreed "to prioritise the implementation of the connectivity-related BRI MoU as it relates to ports, roads, rail and air links and overall communications activity within the Trans-Himalayan Multi-Dimensional Connectivity Network." In a telling aside, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang, who hosted the visit, said: "I now have every hope that a Free Trade Agreement can be concluded in the very near future."

Overall, though, the most significant development to emerge as a result of the visit was the green light given to extending China's Tibetan rail network from its current terminus, close to the Nepal border, to Kathmandu. This will connect the Nepalese capital to Lhasa and plug into the wider mainland rail resource. Although some aspects of the project have yet to be finalised, China has already agreed to fund an in-depth feasibility study of the proposed extension.

With this initial study set to be completed next month – which will then be followed by a more in-depth two-year review – it is now expected that this line will become operational in 2025. In total, the project will require the laying of some 540km of additional track.

At present, estimates as to the final cost of the project vary from US$2.5 billion to $8 billion, a figure that Nepal – given that its total annual GDP is just above $20 billion – would struggle to find on its own. At present, there seems to be a tacit assumption on the part of Nepal that China and India, its other giant neighbour, will somehow cover the costs of both this extensive infrastructure upgrade and several of the energy projects already underway. If the bill was left for Nepal alone to carry, it is believed this overhead would prove a crippling burden for the country for generations to come, with no real ROI likely until well into the 22nd century.

All of which highlights another problem for the mountain kingdom – while looking to ensure its own economic development stays on course, it has to maintain a tricky balancing act, neither overtly-favouring nor inadvertently alienating China or India, its two suitors who, somewhat awkwardly, remain more competitive than co-operative. To complicate matters still further, while India has long had a quasi-monopoly on Nepal's external and internal trade, government figures in Kathmandu have made no secret of their desire to be a little more promiscuous, a development that their New Delhi counterparts have already intimated disapproval of.

This, however, has not deterred China from openly wooing its 30-million-strong neighbour at a time when India appears to have tightened its own purse strings. In 2017, for instance, Beijing pledged $8.3 billion in support of Nepal's infrastructure and energy development projects, more than 26 times the $317 million forthcoming from India over the same period.

Despite the clear challenges that remain, the potential size of the rewards on offer may yet prevail. From China's point of view – given that one of the key BRI aims is to open new markets for its more underdeveloped western regions, including Tibet and Xinjiang – establishing an effective trade route into India via Nepal remains a clear priority.

In order to deliver on this, mainland officials have already mooted the idea of a tripartite China-Nepal-India trade corridor, a similar arrangement to the existing China-Pakistan-India initiative. To date, India has refused to play ball. This is despite the fact that, as Nepal borders Uttar Pradesh, one of India's key food production and manufacturing hubs, a direct route through to China would clearly be in its own interest. Given the clear win-win-win on offer to all three prospective participants, there is still a strong belief that agreement on tripartite trade connectivity may yet be reached.

Geoff de Freitas, Special Correspondent, Kathmandu

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Michal Makocki, Senior Associate Analyst, European Union Institute for Security Studies

Introduction

China’s regional approach to the EU’s neighbourhood is shaped by its flagship Belt and Road Initiative. Reviving the image of the ancient Silk Road, through this massive infrastructure project Beijing aims to re-connect Europe and Asia and to link China to markets in Europe and beyond. This has inevitably attracted the attention of countries in Eastern Europe and the South Caucasus, which in ancient times contained key transit and trading posts before the land routes were gradually superseded by maritime routes which proved faster and more economical. China-backed overland routes boost expectations among these countries of tangible benefits such as new infrastructure construction, transit fees, modernisation of the trade sector, improved connectivity with China’s booming market and ultimately enhanced geopolitical significance. Chinese engagement is also welcomed as it helps diversify Eastern Partnership (EaP) countries’ trade relations beyond their traditional markets, in particular the Russian market. Or so the Chinese slogan promises. Too often Chinese plans lack concrete details: doubts over their implementation, feasibility and viability abound. And most importantly, China’s official slogans focus on economic benefits but gloss over the geopolitical reality of the new routes which may potentially alter the balance of power in the region. This chapter firstly describes the implications of China’s Belt and Road project for the EU neighbourhood, then goes on to examine the region’s responses to the initiative and, finally, attempts to gauge the geopolitical consequences of the project, with a focus on Russia and the EU.

Reactions in the region

Belarus has acquired (together with Russia and Kazakhstan) a pivotal role for the Chinese corridors. Proximity to the European market gives Belarus an edge in attracting Chinese investments, sought not only because of their economic value but also because they offer a coveted source of diversification from the dominant economic partnership with Russia. China has invested in the creation of the Great Stone China-Belarus Industrial Park, which is supposed to support joint production and logistics hubs. Few companies have actually made use of the park so far, but direct connections to Shenzhen (China’s innovation hotspot on the border with Hong Kong) may change that.

Ukraine’s geographical position rivals that of Belarus but the conflict with Russia means that China has adopted a cautious attitude towards the country. Ukraine offers the shortest route between China and Europe (through Kazakhstan, Rostov and Donbass) but due to continued hostilities in Donbass as well as Russia’s transit ban, China has until recently suspended sending its cargo through Ukraine to Slovakia and further on to Europe. The conflict between Ukraine and Russia has also derailed other potential investments from China. Before the annexation of Crimea China was planning to build a deep-sea port in Crimea, a plan which was obviously forestalled by Russia’s annexation of the peninsula. Currently other Ukrainian Black Sea ports are being discussed as alternatives for Chinese investments but without any concrete results at this stage.

Ukraine’s signature of a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) agreement with the EU offers significant opportunities for cooperation with other countries, including China, but until the conflict subsides and Russia lifts its transit ban there is little scope for increased cooperation with China. Ukraine’s key objective in its engagement with the Chinese Silk Road initiative will be to find an alternative supply route which would circumvent Russia. A trial train project was launched immediately after the imposition of the Russian transit ban to transport Ukrainian cargo to China via the Trans-Caspian corridor but it never became fully operational. In terms of infrastructure investments, Ukraine’s upgrading needs are substantial but so far the experience with Chinese projects has been discouraging. A Chinese loan for the construction of a high-speed rail link between central Kyiv and Boryspil airport has been linked with corruption under the Yanukovych administration and had to be renegotiated.

Azerbaijan is being forced by low commodity prices to diversify its economy beyond its traditional reliance on hydrocarbon exports and welcomes the opportunities offered by the Chinese project. Infrastructural improvements in the port of Baku have taken place, helping establish regular connections with Kazakhstan’s Caspian port of Aktau. With the recent opening of the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars (BTK) railway, the corridor will be able to rely on a connection from the Azeri Caspian coast through Georgia and Turkey to the European railway network. However, expectations of significant cargo flows from China have to be assessed against their business rationale. The Trans-Caspian corridor is more expensive than other Chinese routes as it involves a number of points where cargo has to be shifted from trains to vessels or vice versa, thereby increasing the overall costs. It is also interesting to note that Azerbaijan has suddenly acquired importance on the crossroads not only of East-West but also North-South routes, as it is primed to be a transit point along the so called North-South Transport Corridor linking Russia with Iranian ports (however, substantial investments are still necessary on the Iranian portion of the railway, to be financed with Azeri loans). Whether any of these corridors brings Baku benefits beyond not-so-substantial transit fees, will depend solely on Azerbaijan as it firstly needs to build its industrial base virtually from scratch. Chinese investments and the outsourcing of Chinese overcapacity may indeed facilitate this.

Georgia has quickly grasped the potential offered by trade diversification and signed a free trade agreement with China. Together with the DCFTA with the EU, it offers an attractive regulatory package for Chinese investors looking for facilitated access to the EU market. It is also working to improve logistical connections with both of its trading partners. In particular the above-mentioned Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway link and new port on the Black Sea coast in Anaklia (built by a Georgian-American consortium) will be pivotal.

Moldova and Armenia seem to have been largely left behind by the Chinese initiative. China Shipping Group has launched container services in Giurgiulesti, the only Moldovan port on the Danube. But other than that Moldova does not present much interest to China in terms of the BRI. Similarly, connections through Armenia do not seem to offer much added value for China.

Eastern promises…

The Belt and Road project holds two major promises for the EaP countries. First, expanded trade relations with the world’s second-biggest economy will lead to trade diversification. Many countries in the region suffer from tense relations with Russia, which leverages its trade policies for political purposes. Moscow has for example imposed a transit ban on Ukrainian goods. In 2006, at a time of deteriorating relations with Moldova and Georgia, it banned imports of wine from both countries. It may also suspend trade benefits attached to the Commonwealth of Independent States’ Free Trade Area (CIS FTA) or use sanitary and phytosanitary rules to impede access to its market, even for members of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU). From this perspective, the Chinese market offers significant potential for diversification. However, while growing in importance, China’s share of the region’s trade remains small (for example, in 2016 Ukraine’s trade with China amounted to €5 billion or 8% of Ukraine’s total trade). The significance of the Chinese market may change with the improved transport connections. Geopolitically, the Trans-Caspian route in particular offers a way to circumvent Russia, thwarting any future attempts by Moscow to use the transit ban against any of the EaP countries.

The second promise of the Belt and Road initiative is that of increased investments in infrastructure. However, Chinese investments may not be a silver bullet for EaP countries’ infrastructure deficit. China’s model of infrastructure deals is less attractive than that of the EU, which involves grants rather than loans, especially under the Neighbourhood Investment Facility.

…and challenges

The initiative also presents certain challenges. The EaP countries will need to make sure they do not serve as mere transit points but rather are able to use the new corridors to increase their market share in China. For the time being, the fastest growing market will be the EU, with China possibly trailing even behind the US and Turkey. This will justify prioritisation of scarce domestic resources for infrastructure connections with Europe rather than China. Also it is important to remember that customs and trade facilitation often brings faster and much cheaper improvements in logistical efficiency than costly infrastructure investments. On another note, improved connections with China will increase imports and, hence, competition among domestic producers. If such competition compels them to move up the value chain, so much the better, but it might trigger economic dislocation.

Chinese pragmatism is double-edged. While China helps Ukraine circumvent Russian transit bans, Chinese companies have shown interest in building a bridge between annexed Crimea and the Russian mainland. Chinese investments in separatist territories in the region may further fuel conflicts. Beijing’s own rapprochement with Moscow may limit China’s potential to play a positive role in the neighbourhood. For example, Russia forced China to formally acknowledge Russia’s role in the post-Soviet space and agree to consider the ‘interests of Russia during the formulation and implementation of Silk Road projects’. China has already demonstrated that it will respect Russia’s perceived sphere of influence and displayed reluctance to invite interested countries such as Ukraine and Moldova to join the so-called 16+1 platform for cooperation between China and the EU.

For the EU, the Chinese initiative is also a double-edged sword. Firstly, China may aim to tap into Caspian energy resources and compete with the EU for access to them. Chinese energy companies have been cooperating with Turkmenistan to develop offshore gas deposits and have built a network of pipelines from the region to China. Secondly, the Chinese project may bring economic growth and help build the region’s resilience. But that will only happen if Chinese projects are placed on a sustainable footing, do not undermine EU reforms and do not facilitate corruption.

Conclusion

It remains to be seen if China’s ambitious project will bring the benefits to the region that Beijing has often promised. Transit countries enjoy little value added. Fear of dependence on Russia drives many countries to welcome connections to China’s market. But multiple corridors will mean that ultimately it will be China who will maintain the geopolitical leverage thanks to the ability to switch between them whenever conditions so dictate. Also China’s growing economic presence, coupled with skilful diplomacy, may eventually herald mounting political influence in the region. This would add a new layer of complexity to an already complicated political landscape.

This article was originally published as a chapter in Chaillot Paper No. 144, “Third powers in Europe’s east” (EUISS, March 2018), and is reproduced here with the permission of the Institute. Please click to read the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

中國外經貿企業服務網

中國對"一帶一路"沿線國家直接投資現狀

中國對"一帶一路"沿線國家直接投資起步較晚,遲至2007年才開始大規模直接投資。但在過去的10多年間,中國對"一帶一路'沿線國家OFDI一直保持了較快的增長速度,呈現出如下特點:

1. 持續快速增長趨勢

從流量看,據《中國對外直接投資公報》統計,2003年中國對"一帶一路"沿線64個國家OFDI流量僅2.02億美元,2015年飆升到189.3億美元,同比增長38.6%,年均增速高達46.0%,比同期中國OFDI總流量年均38.8%的增速快7.2個百分點,占中國OFDI總流量的比例也從 7.1%上升至 13%。從存量看,2003年,我國對"一帶一路"沿線國家的直接投資存量為13.2億美元,佔我國對外直接投資存量的4%,2015年,這一指標飆升為1156.8億美元,佔中國對外直接投資總存量的10.5%,2003年-2015年,中國對"一帶一路"沿線64個國家投資存量年均增速高達45.2%,比同期中國對外直接投資總存量的增速快11.4個百分點。

2. 近鄰化分佈趨勢

近些年,我國對"一帶一路"沿線國家投資在空間分佈上,呈現出先近後遠的特徵。按照規模大小,目前我國對外直接投資最集中地區依次為東南亞、北亞(俄羅斯和蒙古)、中東、中亞和南亞,除中東地區外,均為我國鄰國。其中東盟10國是我國對"一帶一路"沿線國家直接投資最集中的地區。

3. 集聚化趨勢

從空間分佈來看,中國在"一帶一路"沿線國家OFDI金額有明顯集聚化趨勢。截至2015年,有15個國家承接我國對外直接投資存量超過20億美元。據此,作者計算了首位國家集中度等指標。結果發現,無論是首位國家集中度、前3名國家集中度、前5名國家集中度,還是前10名、前15名國家集中度都基本隨著時間序列的推進,呈現出比較明顯的集聚化趨勢。

4.東道國排名變化大,與大宗商品價格漲落保持一致性的順週期性趨勢

近年來,我國對"一帶一路"沿線國家的投資還出現了東道國年度排名變化比較大,與大宗商品價格漲落保持較明顯一致性等順經濟週期性特徵。從流量上看,2014年有10個國家承接我國對外直接投資流量超過了5億美元,但在2015年,只有8個國家超過了5億美元,除新加坡、俄羅斯、印尼、阿聯酋和老撾5國外,巴基斯坦、泰國、伊朗、馬來西亞和蒙古5國直接出局,新增了印度、土耳其、越南3國。而資源豐富的中亞、北亞和西亞地區,近年來隨著大宗商品價格走軟,已經變成了我國主要的撤資地區,其中哈薩克斯坦撤資25.1億美元,伊朗撤資5.5億美元,分別名列我國總撤資榜的第2位和第4位。這表明我國對外直接投資具有非常明顯的順週期性,這種結構並不利於我國在"一帶一路"沿線國家獲取穩定的資源供給。從存量看,東道國排名也顯現出明顯的變化。2015年,承接我國OFDI存量累計超過40億美元的國家一共有8個,依次是:新加坡、俄羅斯、印尼、哈薩克斯坦、老撾、阿聯酋、緬甸、巴基斯坦。其中,阿聯酋進步最大,從第14位前進到了第6位;蒙古則退步最大,從第7位退到了第10位;哈薩克斯坦雖然只從第3位退到了第4位,但對其投資存量大幅下降了32.4%。

5. 產業多元化和升級化趨勢

近十年以來,中國對"一帶一路"沿線國家投資的行業結構呈現多元化和升級化趨勢。從三次產業角度劃分,我國直接投資主要分佈在農業、能源、金屬、化學、其他工業和公用事業等第一產業和第二產業,第三產業占比雖僅15.6%,但其佔比不斷提升。其中2005年-2011年,第三產業佔比平均為7.6%;2012年-2016年上半年,第三產業佔比升至24.9%,2012年和2016年上半年佔比還分別升至34.2%和35.1%,產業升級特徵明顯。如表5所示,中國投資是先從能源、化學等行業起步,2006年開始擴展到農業、金屬、交通、地產等行業,2007-2009年又拓展至科技教育、金融等更高技術含量行業,2012-2013年開始涉足娛樂和旅遊等服務業,2015年以後還涉足公用事業,呈現出從資源導向到資金密集型行業,進而升級到高科技和現代服務業的發展趨勢。

總體來講,"一帶一路"沿線國家目前還不是我國對外直接投資的主要對象,中國對其投資尚比較有限。目前中國對"一帶一路"投資主要流向有較穩定合作機制的周邊國家,例如中國東盟自貿區中的新加坡、印尼、緬甸和老撾等國,上海合作組織中的俄羅斯和哈薩克斯坦等成員國及印度、巴基斯坦、蒙古等觀察員國。值得提到的是,近年來中國對老撾、緬甸、柬埔寨和蒙古等欠發達鄰國的直接投資有了較大增長,但對經濟發展水平更高、制度環境也更為穩健的東歐諸國以及東盟中的馬來西亞、泰國直接投資的重視程度則明顯不夠。當然,由於近年來主權糾紛,中國對菲律賓、越南的直接投資也不多。

中國對"一帶一路"沿線國家直接投資中存在的問題

鑒於"一帶一路"沿線國家多處地緣政治敏感區和風險集中帶,這使得我國OFDI面臨的問題比較多,具體說來,主要表現在:

1.空間分佈不合理,大多數東道國投資環境不好

鑒於中國OFDI有近鄰化趨勢,而這些國家投資環境卻大多不太理想。根據中國電子科學研究院2016年所編制的"絲路信息化指數","一帶一路"國家總體得分均不高,其中得分最高的為新加坡,評分為7.05;排名最低的國家為不丹,評分僅為2.93。從地區分佈來看,中東歐國家信息化投資環境最為成熟,平均得分在4.88分,但我國對其投資非常少。東南亞居其次,平均得分4.81,是我國對外投資分佈最多的地區。獨聯體國家平均得分排名第三,但除俄羅斯外,我國對其直接投資都不多。中東和中亞國家雖普遍在能源資源方面具有強大保障能力,也是我國直接投資分佈較集中的地區,但其平均得分分別為4.47和4.03。南亞國家平均值僅為3.62,大多數國家在基礎設施建設方面非常薄弱,但近幾年我國對其投資卻增長很快。很顯然,中國OFDI這種空間佈局不是太好,有重構必要。

2.對外直接投資行業集中,投資失敗案件比較高

長期以來,中國對"一帶一路"沿線國家OFDI的行業分佈一直比較集中。據Merger market數據,在2005年至2016年6月這段時間內,中國對"一帶一路"沿線國家跨國並購的行業分類數據中,排名前五名的行業分別是能源(佔比55.6%)、金屬開採及冶煉業(佔比11.6%)、交通製造業(佔比8.2%)、地產業(佔比6.8%),表現出非常明顯的資源尋求型特徵,資源類並購佔比67.2%。雖然近年來,中國對"一帶一路"國家投資已經開始多元化,但總體尚未形成規模。從某種意義上說,這種行業結構也是一把"雙刃劍":一方面,通過OFDI,中國獲得了大量的資源補給,緩解了我國經濟高速增長導致的資源不足問題;另一方面,便利資源的獲得,也會弱化國內產業結構升級的動力。隨著近些年美聯儲不斷加息和中國經濟進入新常態,國際大宗商品價格出現明顯下滑,這不僅使相關產業投資不斷萎縮,也使東道國對我國資本的疑慮不斷加重,中國OFDI風險不斷累積。據Heritage Fundation統計,從2005年至2016年上半年,中國對"一帶一路"國家投資失敗案件51宗,失敗金額686.8億美元,明顯高於其他地區佔比。其中能源業投資失敗佔比69.5%;金屬業佔比9.2%;而且從年度數據看,這些行業的投資失敗事件出現最為頻繁。

3."走出去"企業多為國有企業,而且主要是央企

目前"一帶一路"建設仍處於初期階段,以"道路聯通",即基建、運輸等項目為主。但從投資規模來看,央企是中國對"一帶一路"沿線國家開展投資的主力軍,地方企業和民營企業只能發揮補充性作用。據Heritage Foundation統計,截至2016 年上半年,央企對"一帶一路"沿線國家大型項目投資的存量為1333.1億美元,佔中國對“一帶一路”大型項目投資總量的69.3%。與那些具備豐富投資經驗的跨國公司和開發銀行相比,中國企業甄別有利可圖的項目和控制風險的能力更差。隨著海外基礎設施貸款迅速增加,由於信息披露較慢,還款期更長,這些投資未來可能會為中國金融體系帶來新一輪資產質量問題。

4.培育競爭對手,可能導致產業"空心化"

長期以來,中國企業由於缺乏管理、技術、品牌和渠道等競爭優勢,面對日趨激烈的國際市場競爭時,只是一味依賴國內的低成本勞動力優勢。因此,在對外直接投資過程中,就比較容易培養競爭對手,導致國內相關產業出現"空心化"現象。例如紡織業,隨著我國對越南、印度投資力度的加大,當地興起的相關競爭企業越來越多,這些發展中國家企業在美國等第三市場的份額越來越高,進而導致我國紡織產業競爭優勢不斷下降,甚至導致一定程度的產業空心化。類似的行業還有家電、箱包等行業。

請按此閱覽原文。

Editor's picks

Trending articles

In September 2015, the China-Britain Business Council released a comprehensive new report on China's ambitious and complex "One Belt One Road" initiative in partnership with the Foreign & Commonwealth Office. Designed as a practical guide to where the opportunities lie for UK companies, the report contains succinct chapters on the seven key sectors and 13 major regions to help you understand what the implications are in your industry and where your next steps should be.

"UK business is poised to play an integral part ...

New markets will open and new supply chains will change the way goods move across the globe."

HM Ambassador Barbara Woodward

For more details, please see www.cbbc.org/sectors/one-belt,-one-road.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By PwC China

Summary of Major Discoveries

- Since 2014, the overseas investment transactions made by enterprises based in mainland China in the medicine field have surged, with the transaction volume climbing by over six times, the transaction amount in the first half of 2017 reaching USD4,353 million (approx. CNY28.95 billion), and the compound annualized growth rate increasing to 85%. Two reasons explain this phenomenon: on the one hand, the booming Chinese M&A market results in a declined number of quality targets with higher valuation, thus domestic enterprises shift their focus to the overseas to acquire target companies at a more proper valuation; on the other hand, the Chinese yuan is under pressure of devaluation in recent years, driving domestic enterprises to acquire overseas assets.

- Private enterprises dominate the overseas medicine M&A market, whose transaction amount in recent three years is as high as 21 times that of SOEs. This is in line with Chinese government’s support of medical cause run by non-governmental sectors, and the increasingly important role of private businesses in the medical and health market.

- In terms of specific industries, different from the medical instrument industry, domestic enterprises prefer to make overseas investment transactions in the bio-pharmaceuticals industry. However, regardless of the segment, domestic enterprises that engage in overseas investments mainly aim at introducing the overseas advanced medical resources or business model into China, to accelerate its domestic strategic layout in the healthcare business, and take the acquired firms as the platform for global expansion.

- In terms of investment destination, Chinese enterprises remain preferring to invest in the healthcare industry of developed regions such as Europe and North America. The major reason is that these countries and regions are equipped with the most advanced medical technologies, platforms and brands in the world, and have immense and mature consumption markets.

- Compared with the overseas M&As by domestic enterprises, foreign companies engage in much fewer transactions in the medicine field in China, with the transaction amount much smaller as well. It demonstrates that in the medicine investment area, “going out” outpaces “bringing in” of overseas resources, and the main reason is that domestic pharmaceutical enterprises have much space to improve their R&D capacity.

Outlook

- The central government released the Notice on Further Guiding and Standardizing Overseas Investment Directions in August 2017, which as clearly specified that “priority should be given to promoting overseas investment of infrastructure that is conducive to ‘One Belt, One Road’ development and connectivity of surrounding infrastructure”, “investment cooperation with overseas hi-tech enterprises and advanced manufacturing enterprises should be intensified, and setup of overseas R&D centers encouraged”; the Notice has provided a good policy foundation for domestic enterprises to invest in the overseas medicine field, particularly in the countries along the “One Belt, One Road”. Hence, the growth trend in the medicine investment by Chinese enterprises is expected to continue.

- In light of the “One Belt, One Road” strategy, Asia-pacific region is expected to be an emerging investment destination focused by Chinese investors. At the same time, the countries and regions in Europe and North America, domestic investors, especially private businesses, perhaps face greater pressure and challenges in overseas investment. For instance, in acquiring high-tech firms in the sensitive industries, in February 2016, a semi-conductor manufacturer rejected the USD2.6 billion takeover offer of a company under China Resources (Holdings) Co., Ltd., due to the regulatory pressure of American authority.

- Moreover, with the continuous promotion of the “One Belt, One Road” strategy, an increasing number of overseas investors may access China to invest in the medicine field, particularly in the areas that promote development of the pension services in China.

Please click to read the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Chris Devonshire Ellis, founding partner, Dezan Shira & Associates

An issue when composing a book such as this, covering such a large geographical area, is the definition of what Asia actually is. This becomes especially pertinent when dealing with Asian subcategories like “Eurasia” and “Central Asia”. What do these really mean? Indeed, what is “Russia”?

Asia is defined by Miriam-Webster as “A continent of the eastern hemisphere north of the equator forming a single landmass with Europe” and further revealed to possess “numerous large offshore islands including Cyprus, Sri Lanka, Malay Archipelago, Taiwan, the Japanese chain, & Sakhalin area”.

Which taken literally would mean that the southern islands of the Maldives, being south of the equator, are not part of Asia. Neither are Indonesia and Singapore. Meanwhile, Australia, a continent in its own right and almost exclusively “south of the equator”, has also declared itself part of Asia. Existing definitions, which we have grown used to, are therefore in need of some adjustment.

Central Asia is equally tricky. Most people would identify it as a collection of Muslim states, lying directly south of Russia, and previously part of the Soviet bloc. However, this doesn’t really work. Mongolia is for example Buddhist, as many of the currently Muslim territories once were, while its capital, Ulaan Baatar, is as close to Anchorage in the United States as it is to Moscow.

Even Eurasia can be difficult. The majority of people would imagine this area to extend roughly to the boundaries of the further reaches of the Mongolian Empire at its height – including all of China, and as far west to Hungary in Eastern Europe. “The Steppes” is an expression often used to describe Eurasia. Miriam-Webster again: Eurasia is “The landmass of Asia & Europe - chiefly used to refer to the two continents as one continent”.

Russia meanwhile acknowledges its unique geographic position by maintaining the Double-Headed Eagle as its national symbol. One head faces west, the other east. Although its capital city is in the European part, 75 percent of Russian territory lies in Asia. When thinking of Asia, images of steamy jungles and elephants tend to come to mind, yet the region has a long coastline above the Arctic Circle, previously home to the elephant’s distant cousin, the mammoth. As global warming increases, we may become more familiar with the concept of Arctic lands being Asian.

The reason these definitions are changing is largely due to the rise of China, a re-think of its role in the world and its revision of domestic and foreign policy. As China spreads its influence beyond its own borders, those of us from white European stock should be reminded that the term “Caucasian” typically used to describe us in terms of race includes the word “Asian”.

For the purposes of this book however, and in accordance with Miriam-Webster’s definition of “Eurasia”, this analysis views the subject as including all of Asia - meaning from Arctic Siberia, south to countries such as Sri Lanka and Indonesia, and West to India, Pakistan and Iran. It also includes Europe because, as we will see, China’s Silk Road Economic Belt will impact upon all.

Please click to read the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By CITY BUSINESS Magazine (College of Business, City University of Hong Kong)

After a century of marginalisation, Central Asia transit routes are once again taking centre stage. City Business Magazine editor Eric Collins investigates the nature of the historical Silk Road, and asks why China is unveiling a new version for the 21st century.

Sinuously the Silk Road flows from ancient times down to the present. From China through the Taklamakan Desert to Samarkand at its centre, through the grassland steppe of Central Asia to the shores of the Mediterranean, it helped pioneer globalisation. Romantically we imagine spices, silks, perfumes and precious stones wending their way by camel between China and Europe. But what was the nature of this Road? Who and what travelled along it and in what direction? Was it just confined to goods? Or did ideas make the journey as well? How Broadband was this historical Silk Road? And how does it relate to its latter-day successor, the recent China development policy initiative, One Belt One Road (OBOR)?

Please click here for the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Zhao Minghao (He is a research fellow at the Charhar Institute and an adjunct fellow at the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at Renmin University of China. He is also a member of the China National Committee of the Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific.)

Major American think tanks are beginning to take the “Road and Belt” initiatives seriously. Recently the Center for Strategic and International Studies cosponsored a symposium on the “Road and Belt” with the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies of Renmin University of China. The CSIS has also launched its own “Reconnecting Asia Research Initiative”. Scholars with the Brookings Institution, Center for American Progress and National Bureau of Asian Research have also started corresponding research projects.

US “overreaction” to Chinese proposals has created obstacles to development of China-US relations over the past few years. In fact, Washington could have responded in more appropriate and smarter ways. The US government took great pains to dissuade European allies from joining the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank headquartered in Beijing, on the grounds that the institution can’t meet the “highest global standards” in management and lending. Yet Britain, Germany and France chose to become AIIB founding members despite US opposition.

Financial Times chief commentator Martin Wolf, who had worked with the World Bank, said what the US was truly worried about was that China-initiated mechanisms may undermine American influence on the global economy, and Britain’s decision to join the AIIB was a significant blow to the US. Wolf was straightforward in pointing out that rise of the Chinese economy is both desirable and unavoidable, the world needs fresh mechanisms, and will not stop its progress just because the US refuses to participate. (Martin Wolf, “A Rebuff of China’s AIIB Is Folly”, Financial Times, March 24, 2015)

On April 13, AIIB president Jin Liqun and World Bank president Jim Yong Kim signed their institutions’ first framework agreement on joint fundraising. The agreement will allow the two parties to jointly fund development programs, meaning that the two international institutions have taken an important step forward in meeting the world’s tremendous demands for infrastructure. Before that, the AIIB had agreed with the US-and-Japan-dominated Asian Development Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and the British Department for International Development on fundraising for development projects. The AIIB is expected to approve about $1.2 billion in fundraising programs, including support for road construction in Pakistan and Central Asia.

For Beijing, the AIIB is a test rather than a so-called triumph against the US. This is the first time for the Chinese to attempt to provide public goods in the field of international development, indicating Beijing is actively embracing multilateralism in global governance. Chinese leaders have sufficient motivation to support the AIIB to develop in a manner in conformity with the principle of “lean, clean, green”. The AIIB is expected to demonstrate higher efficiency, zero tolerance to corruption, and commitment to sustainable development. In particular, the AIIB hopes its staff would be a third of the World Bank’s when its registered capital equals that of the latter.

Fundraising needs for infrastructure investments will reach $10 trillion in the next decade. There will be no competition between the AIIB and other multilateral development institutions, such as the World Bank and Asian Development Bank. Instead, there is broad room for them to cooperate. Jin has stated on multiple occasions that American companies would not be excluded from the AIIB’s scope of business. American lawyer Natalie Lichtenstein, who had worked for the World Bank for nearly 30 years, has been hired by the AIIB as an adviser. The AIIB has its eyes on talents’ qualifications and capabilities, not which country’s passport he or she holds.

Beijing has also been open to Washington regarding the “Road and Belt”. During his visit to the US in September 2015, Chinese President Xi Jinping stated in explicit terms that the US is welcome to participate in the initiative.

In order to promote Afghan economic development and economic integration in Central and South Asia, the US put forward the “New Silk Road” program in 2011. By 2014, the program had been further focused on four main fields, namely developing regional energy markets, promoting trade and transportation, upgrading customs and border control, enhancing business and personnel exchanges. This is very similar to the goals of the China-proposed “Silk Road Economic Belt”, so it should be possible to dovetail the two programs.

In fact, China and the US have already been collaborating on Afghan affairs in the past few years. Now they need to take one bolder step forward. They can jointly support construction of such infrastructure facilities as power grid, upgrade of border facilities, and negotiations on border trade agreements. China and the US can also cooperate under such frameworks as the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation Program. In June 2015, Richard Hoagland, a senior official with the US Department of State, talked with officials with China’s National Development and Reform Commission on how to make the “New Silk Road” and “Silk Road Economic Belt” mutually complementary.

Beijing does not expect the Obama administration to enthusiastically support the “Road and Belt”, but it does hope that the American side can be serious about the tremendous potential for the two countries to formulate a global development partnership. The “Road and Belt” has offered a window of opportunities. The US should not overreact to every Chinese proposals. They are not in a zero-sum game. As veteran China expert Harry Harding said, “a more successful and confident United States would regard the rise of China with greater equanimity”. In the realm of international development, Washington doesn’t need to panic, it should instead be confident and take a different attitude – let China succeed.

Please click here to view the full article on the website of China-United States Focus.