Chinese Mainland

By King & Wood Mallesons – Neil Carabine and Stephanie Courtice

China’s outbound foreign direct investment (FDI) has increased substantially over the past decade. China’s 13th Five Year Plan has also encouraged acquisitions and investment by Chinese organisations in a wider range of sectors (e.g. fintech, high-end manufacturing and real estate).

With the implementation of the BAR initiative, Chinese investors will continue to play an increasingly significant role in global markets. In this publication, we look at some of the central steps investors can take to mitigate their risks and take advantage of the legal protections available to safeguard their outbound investments.

Tip 01: Understanding the key risks for outbound foreign investment

As well as providing opportunities, large-scale foreign investment projects face numerous risks. Understanding how to assess, navigate and mitigate these risks is key to project success. Key risks associated with outbound FDI include:

- Country operational risk – risks associated with corruption, national security, political stability, government effectiveness, the legal and regulatory environment, the macroeconomic situation, foreign trade and payments, local labour markets, tax policy and the standards of local infrastructure;

- Political risk – the risk of policy changes on exchange rate and interest rate controls, international sanctions, changes of regime and economic changes, controls on prices, outputs, currency and remittances, labour quotas and, in some cases, nationalisation or expropriation. Political risk may also result from events outside of government control, such as war, revolution, terrorism, labour strikes, extortion, and civil unrest; and

- Credit risk – one of the major risks of outbound FDI is the potential for the host country to default on foreign lending and / or investment projects. This risk is particularly high in a number of BAR countries, which lack sound creditworthiness. The graph below sets out the overall country credit risk of certain BAR countries. Investors should also be aware that during periods of financial crisis, governments may be excused from providing the substantive protections granted under bilateral investment treaties (BITs).

Tip 02: Mitigating corruption risk

Anti-corruption due diligence

Given the penalties under certain investor state laws and the huge commercial risks of investing in a corrupt entity, it is essential that adequate anti-corruption due diligence is undertaken into:

- the entity’s control environment: policies, procedures, employee training, audit environment and whistle-blower issues;

- any ongoing or past investigations (government or internal), adverse audit findings (external or internal), or employee discipline for breaches of anti-corruption law or policies;

- the nature and scope of the entity’s relationship with the government (both family and corporate relationships) and the history of significant government contracts or tenders;

- the entity’s important regulatory relationships, such as key licenses, permits, and other approvals – with a focus on employees who interact with key regulators; and

- the entity’s relationships with distributors, sales agents, consultants, and other third parties and intermediaries, particularly those who interact with government customers or regulators.

Tip 03: Factoring in the ongoing cost of foreign investment regimes

Regulatory issues

Foreign investors often face unpredictable approval regimes. Navigating government decision-making processes can result in delay and increased costs. Even in historically investor-friendly jurisdictions, foreign investors can face challenges and political opposition when the privatization of public assets is involved.

Foreign investment rules

It’s not just caps on ownership. For example, some BAR countries (e.g. the Philippines) prevent foreign nationals from holding executive roles in locally incorporated companies, leading to excessive executive costs associated with engaging a local CEO and a ‘real’ CEO to shadow their local counterpart.

Additionally, some jurisdictions allow initial foreign ownership but require the foreign investor to sell down to a local partner over time, which can lead to a fire sale of assets and depressed pricing. For example, Indonesia requires foreign companies to sell down stakes in local mining operations and increase domestic ownership to 51% by the 15th year of production.

Conclusion

Effective planning and management of outbound FDI projects is key to allowing investors to mitigate risks and maximize the protections available. In particular, investors should:

- engage external advisors at an early stage to help evaluate and navigate the risks associated with potential investments;

- structure investments to maximise the protections available under BITs; and

- ensure effective deadlock and exit mechanisms are incorporated in joint venture agreements to allow for a smooth exit in the event that things do go wrong.

Please click to read full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Massive China-backed road network and port expansion programme tipped to sustain country's economic surge.

At the end of last month, Cambodia's Ministry of Public Works and Transport (MPWT) announced that work had been completed on 2,000km of new roads, seven major bridges and a container terminal servicing the Phnom Penh Autonomous Port. Tellingly, all these initiatives had largely been backed by China, with funding provided from within the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The announcement was triggered by the official opening of a section of National Road No. 6, a 251km stretch connecting the provinces of Kampong Cham in the southeast with Siem Reap in the northwest. The road has a particular economic significance in that it provides a direct and rapid link between Phnom Penh, the Cambodian capital, and Angkor Wat, the country's principal tourist attraction.

It took four years and two months to complete this key part of the country's road network, with the Shanghai Construction Group – the company responsible for much of Shanghai's mid-1990's architectural makeover – acting as the lead contractor. The cost of the project is estimated at about US$255 million, with 95% of that covered by a concessional Chinese loan and the balance made up by the Cambodian government.

While significant in its own right, the work on the road link is just a small part of the BRI-led transformation of Cambodia's transport infrastructure. According to the MPWT, some 70% of Cambodia's upgraded road and bridges have been built with Chinese backing. To date, this includes 2,301km of new roads, with an additional 735km still under construction. Of these, the most recently commissioned is the 96km National Road 11, which was given the go-ahead in March and will connect the provinces of Prey Veng and Tboung Khmum.

Work has been completed on seven of the new bridges, with a combined length of 6.8km. Work on an eighth bridge, spanning the Mekong river, began in February this year with the structure ultimately set to connect the Stung Trang district of Kampon Cham with the Krouch Shmar district of the northwestern Tbong Khmum province. With a construction length of just over one kilometre, the project is estimated to cost $57 million. The principal contractor is again the Shanghai Construction Group, with the work expected to take some three-and-a-half-years and an opening date pencilled in for early 2021.

China's total investment in the redevelopment of Cambodia's roads and bridges now stands at about $2 billion. While there have been some domestic expressions of concern over the size of the debt and the country's apparent over-reliance on China, others have taken a more pragmatic view, arguing that mainland finance is the only game in town if the country is serious about upgrading its infrastructure.

It is generally conceded that, with Cambodia fast becoming a regional manufacturing hub, improved transport infrastructure is all but essential. Given the country's economic growth in recent years, its government has every reason to trust that its escalating debt level will prove to be sustainable. Over the past six years, Cambodia's GDP has grown by an average of 7% per annum, with the current infrastructure redevelopment programme seen as essential for sustaining that momentum. Thankfully, there are signs that the government's faith might not be misplaced.

Already hailed as one of the first real successes to emerge from the ever-closer Phnom Penh-Beijing partnership is the Cambodian capital's Autonomous Port. The facility, the country's largest freshwater port, gained a new container terminal due to a China-sourced concessional loan of $28.2 million.

Once the terminal became operational in January 2013, the port's container loading capacity was trebled overnight, with the aim of processing 150,000 twenty-foot-equivalent units (TEUs) a year. Exceeding even the most optimistic predictions, the port's container throughput totalled almost 180,000 in 2017, some 20% higher than its official target. Should Cambodia's other China-backed infrastructure development programmes come anywhere close to matching the port's performance then, no doubt, any lingering dissenting voices may finally be stilled.

Geoff de Freitas, Special Correspondent, Phnom Penh

Editor's picks

Trending articles

中國外經貿企業服務網

2013年9月和10月,國家主席習近平在訪問哈薩克斯坦和印度尼西亞期間先後提出共同建設"絲綢之路經濟帶"和"21世紀海上絲綢之路"(簡稱"一帶一路")的倡議,得到了沿線國家的廣泛支持和國際社會的高度關注。2015年3月,國家發改委、外交部與商務部聯合發佈《推動共建絲綢之路經濟帶與21世紀海上絲綢之路的願景與行動》(簡稱《願景與行動》),正式將"一帶一路"列為中國新一輪"走出去"戰略重點。"一帶一路"橫跨三大洲,貫通東亞、東南亞、南亞、中亞、獨聯體、西亞北非和中東歐7大區域,涵蓋66個國家,總人口約44億,經濟總量約達21萬億美元,是世界上跨度最長的經濟大走廊。沿線絕大多數國家屬發展中國家和轉型經濟體,經濟發展後發優勢強勁,與中國經濟具有良好的互補性;與此同時,這些國家基礎設施十分落後,是目前制約中國與沿線各國深度合作與共同發展的薄弱環節。為此,《願景與行動》明確指出,基礎設施互聯互通是"一帶一路"建設的優先領域。在尊重相關國家主權和安全關切的基礎上,沿線國家宜加強基礎設施建設規劃、技術標準體系的對接,共同推進國際骨幹通道建設,逐步形成連接亞洲各次區域以及亞歐非之間的基礎設施網絡,從而實現沿線各國多元、自主、平衡、可持續的發展。"一帶一路"基礎設施互聯互通建設是一項長期、複雜而艱巨的系統工程,涉及國家之多、跨越空間之廣前無古人,沿線各國在經濟發展、地緣政治、宗教文化等方面的巨大差異,必然給中國主導的"一帶一路"基礎設施投資建設帶來無法回避的風險和挑戰。為此,深入研究"一帶一路"沿線各區域基礎設施的發展現狀和投資需求潛力,探討中國面臨的投資合作機遇、外在風險與自身挑戰,提出應對思路和策略選擇,對於推進"一帶一路"倡議的順利實施、構建中國全方位對外開放新格局具有重要的現實意義……

中國對"一帶一路"沿線基礎設施投資的進展與挑戰

(一) 中國對"一帶一路"沿線基礎設施投資的進展

從投資規模來看,中國與"一帶一路"沿線國家的基礎設施投資合作規模日益加強。2015年,中國對"一帶一路"沿線60個國家新簽對外承包工程項目合同3987份,新簽合同額926.4億美元,佔同期中國對外承包工程新簽合同額的44.1%,同比增長7.4%;完成營業額692.7億美元,佔同期中國完成營業額總額的44.9%,同比增加7.6%。2016年,中國在“一帶一路”沿線61個國家新簽對外承包工程項目合同8158份,新簽合同額1260.3億美元,佔同期中國對外承包工程新簽合同額的51.6%,同比增長36%;完成營業額759.7億美元,佔同期總額的47.7%,同比增長9.7%。

從區位分佈來看,中國對"一帶一路"沿線國家的基礎設施投資主要集中在東南亞、西亞北非和南亞地區,中東歐地區吸引中國投資的起點較低,但增長迅速,未來潛力巨大。根據商務部《中國對外投資合作發展報告2016》,2015年,巴基斯坦、印度尼西亞、馬來西亞、沙特阿拉伯、老撾、孟加拉、泰國、越南、埃及和土耳其是中國企業在"一帶一路"沿線承包工程領域十個最大的國別市場,其中東南亞國家5個,南亞國家2個,西亞北非國家3個,中國與這十個國家新簽合同額合計570.2億美元,佔“一帶一路”市場的61.5%;完成營業額合計352.2億美元,佔"一帶一路"市場的50.8%。

從行業分佈來看,電力、交通和房屋建築是目前中國對"一帶一路"沿線國家基礎設施投資的重點領域。根據商務部《中國對外投資合作發展報告2016》,2015年,中國企業在"一帶一路"沿線國家承包工程新簽合同額中,電力工程建佔27.4%,交通運輸建設佔16.2%,房屋建築項目佔15.7%。目前,中國企業參與投資合作的巴基斯坦喀喇昆侖公路二期、卡拉奇高速公路、中老鐵路已開工建設,土耳其東西高鐵、匈塞鐵路等項目也正順利推進,這些項目的推進將有效地改善沿線國家的基礎設施條件,有力帶動當地的經濟與社會發展。

中國與沿線國家經濟關係發展勢頭良好,經濟結構互補優勢明顯,現有的合作機制趨向成熟穩定,現有的合作基礎也越來越穩固扎實,這為實現"一帶一路"沿線的設施相通和共同發展目標提供了重要基礎和強大助力。但是,"一帶一路"基礎設施互聯互通建設是一項長期、複雜而艱巨的系統工程,戰略的具體規劃和實施還需進一步完善和細化,中國企業對沿線基礎設施供求狀況瞭解、投資環境適應、風險程度把握、相關信息分析、資金市場運作等都缺乏經驗,戰略的推進實施面臨較大的不確定性。這裡既有來自於沿線東道國的外在風險,也有來自於中國的自身挑戰,既有經濟方面的因素,也有非經濟方面的因素。

(二) 中國對"一帶一路"沿線基礎設施投資的外在風險

大部分國家經濟基礎薄弱,市場機制不健全。"一帶一路"沿線國家多為發展中國家或新興經濟體,整體經濟基礎較為薄弱,經濟結構單一,市場化程度低、法律法規不健全、政府管理水平落後、經濟穩定性差、經濟發展動力不足;也有一些國家國內市場封閉,與中國經濟依賴度較低,外資進入難度大。如果選擇對上述問題十分嚴重的國家進行基礎設施投資,很難依靠市場機制來投資運營,因此會對國內投資企業的利益和分配帶來潛在風險。

部分國家政治風險較高,投資環境較差。東南亞、南亞、中亞和西亞北非等地區的部分國家地緣政治複雜、政權更迭頻繁,再加上宗教、民族矛盾突出以及地緣政治敏感導致部分地區武裝摩擦和衝突不斷,極端主義、恐怖主義和分裂主義盛行,區域政治風險極高,投資環境惡化。而"一帶一路"中的基礎設施建設投資大、週期長、收益慢,項目能否順利推進很大程度上取決於合作國家的政治穩定和對華關係狀況,兩者的矛盾必然對中國在"一帶一路"沿線的基礎設施投資帶來較大的不確定性。例如,由於當地政局不穩,中泰高鐵計劃流產,中緬密松大壩工程被叫停,中國在利比亞、伊拉克、烏克蘭、敘利亞等國的投資也遭遇到困境和損失。

主權爭端局部凸顯,政治互信不容樂觀。東南亞、南亞等部分國家與我國存在有關領土和領海主權的爭端問題,再加上美、日等戰略實施區域外因素的干擾,不僅可能激化既有矛盾,引發沿線國家更多的安全疑慮,甚至還會引爆局部的地緣衝突;少數國家與我國缺乏政治互信,再加上西方大國宣揚的"中國威脅論",導致一些國家對中國推行實施和平發展戰略心存疑慮;還有些國家擔心中國企業投資會衝擊當地傳統產業,破壞當地的資源與環境,等等。這些爭端和矛盾可能會使"一帶一路"所依託的穩定發展環境遭受破壞,對中國在這些國家和地區的基礎設施投資造成壓力和挑戰。

各國利益和制度環境的差異加大協調難度與風險。"一帶一路"基礎設施投資與合作建設涉及相關多國的利益,不同國家存在不同的利益目標,即使同一國家內部的各級政府、企業和居民的利益也存在一定的差異,因此要順利推進中國對"一帶一路"基礎設施投資,必須要建立有效的協調機制,促使各國以及各主體間的利益能夠保持一致性。因此,中國對沿線基礎設施投資必然要承受較高的協調成本和投資風險;另外,沿線各國的政治制度、經濟社會體制、法律和政策體系等也存在明顯的差異,這又進一步加大了國家之間的協調難度,從而也加大了基建企業的投資風險。

中國社科院世界經濟與政治研究所通過借用"經濟基礎、償債能力、社會彈性、政治風險和對華關係"五大指標,對中國海外投資風險進行評級,其中包括"一帶一路"沿線35個國家的風險評級。評級結果表明,"一帶一路"地區的投資風險較高,其中政治風險是最大的潛在風險,而經濟基礎薄弱則是最大的掣肘。從總的評級結果來看,低風險級別僅有新加坡一個國家;中等風險級別包括26個國家,佔35個國家的74%;高風險級別有8個國家,分別為西亞北非的伊拉克和埃及,獨聯體的烏克蘭和白俄羅斯,南亞的孟加拉,中亞的吉爾吉斯斯坦、烏茲別克斯坦和塔吉克斯坦。

(三) 中國對"一帶一路"沿線基礎設施投資的自身挑戰

"走出去"起步晚,企業經驗不足。中國企業海外投資才剛剛起步,基礎設施投資建設項目週期長,設備移動性能要求高,工程難點大,資金需求量大,基建企業大規模"走出去"跨國經營管理、大範圍國際拓展與合作等經驗尚且不足,特別是中國對外承包工程企業在從原有的工程建設承包向股權投融資方向轉變過程中,缺乏成熟完善的運作機制,從而制約了企業"走出去"的步伐。

中國企業海外基礎設施投資缺乏更多融資支持。"一帶一路"基礎設施投資建設資金需求量較大,但目前融資渠道單一,雖然絲路基金、亞投行、金磚銀行等金融機構相繼成立並投入運營,但基礎設施投資的資金缺口仍然巨大。主要原因在於中國企業海外融資中,只有少部分企業選擇境外金融機構(如世界銀行、非洲開發銀行等),大部分境外項目融資支持都是以主權借款和以能源、資源做抵押的借款,而且融資規模比較小;國內金融機構開展外匯貸款的意願不強,政策性金融支持力度非常有限,而且與國際相比,國內融資成本比較高,這又進一步加大了企業境外投資的風險。

國際化專業人才缺乏,專業中介機構能力不強。由於語言限制、文化差異、以及國內專業人才培養不夠等因素的影響,與國際同行相比,中國的涉外會計、律師、諮詢等中介機構的發展程度較低,專業能力不強,特別是涉及國際調研、項目設計、信息諮詢和風險評估等方面能力不足且缺乏國際經驗,這些都會影響中國對外進行大規模和高水平的基礎設施投資。

部分中國企業過於急功近利,缺乏社會責任意識。一些國內企業只注重短期利益,缺乏對項目現實合理性的評判,不顧及項目的前景和當地財政實力,盲目簽約,導致項目停產,如中鐵在委內瑞拉的高鐵項目如今已變成廢墟,75億美元打了水漂。還有一些企業在國內習慣了不顧及自然生態環境,只關注經濟利益,並將這套陳舊的思維模式運用到"走出去"對外基礎設施投資建設中,忽視當地民眾對於環境保護方面的要求,導致投資項目屢屢被叫停。如商務部牽頭、中國企業投資1.8億美元的墨西哥"坎昆龍城"項目,因亂砍亂伐當地森林而墨西哥環境保護署叫停。

請按此閱覽原文。

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Philippe Le Corre, Senior Fellow at the Mossavar- Rahmani Center for Business and Government, Harvard Kennedy School

This chapter focuses on Chinese foreign direct investments (FDI) in Europe, and their potential impact on the landscape of the targeted countries. It examines the investment’s possible connections with the current Belt and Road Initiative (BR), which is primarily billed as an international network of infrastructure projects. With the BR in mind, this chapter asks whether Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOE) can build from their recent experiences in Western Europe, and looks at three main questions: (1) What is the political, economic, and social impact on targeted countries when it comes to public investments in the field of infrastructures? (2) How does it relate to the Belt and Road Initiative? (3) What are the stakes for the cooperation between Chinese investors on the one hand, and local public- and private-sector actors on the other?

The State of Chinese Investments in the European Union

China has almost a millennia-long history of commercial interactions with Europe through the ancient network of trade routes of the original Silk Road. However, these efforts have been redoubled in recent history. This is partly due to the euro debt crisis of 2008; a lower exchange rate for the euro between 2008 and 2016; an ongoing de-industrialization; and a Chinese hunt for world-famous brands and technologies, of which many are in the European Union (EU). According to a 2017 report by Merics and the Rhodium Group, Chinese investments in the EU reached a record $36.5 billion in 2016, up 77% from $23 billion in 2015, which now represents about 4% of total FDI stock in the EU. The United States, in particular, remains a much bigger foreign investor in Europe.

From 2000 to 2016, the top sectors receiving Chinese capital investment were energy, automotive, agriculture, real estate, industrial equipment, and information and communications technology. Chinese state-owned firms also seized opportunities to buy European mining companies, energy assets, and utilities. In 2016, the UK, Germany, and Italy were the three largest recipients of such investments.

China is investing in energy and raw materials in developing countries, and meanwhile looking for opportunities in energy distribution, infrastructure, mergers and acquisitions for brand names, high technology, and market shares in advanced economies. China has also shown a strong interest in airport infrastructures—it took 9.5% of London Heathrow Airport in 2013, 49.9% of France’s Toulouse Airport in 2014, and 82.5% of Germany’s Hahn airport near Frankfurt. China is also active in Eastern and Central Europe, with controlling stakes in Albania’s Tirana Airport and Slovenia’s Ljubljana Airport. In addition, the Beijing Construction Engineering Group (BCEG) is committed in a large £800 million project to redevelop Manchester airport, the UK’s second largest airport.

This wave of Chinese FDI in infrastructure on the European continent started in 2008 in the midst of the euro-debt crisis, when China was offered the opportunity to buy Eurobonds and invest in some of Europe’s infrastructure projects. Bilateral relations between China and EU institutions were also strengthened, and cooperation moved to a new level when President Xi Jinping proposed building a “China-EU partnership” in 2014. China may yet become the largest non-EU contributor to the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI), the initiative launched by the European Commission, with the goal of raising 315 billion euros for stimulating growth and employment. China is expected to contribute 5–10 billion euros to the EFSI. A working group including experts from China’s Silk Road Fund, the European Commission, and the European Investment Bank has been set up to explore opportunities for co-financing….

Lessons to be Learned

It is much too early to make a definitive assessment about Chinese investments in Western Europe in the Feld of infrastructures. The number of compelling cases is limited. Only the Greek case seems worthy of an in-depth analysis because it encompasses several matters that we have alluded to in this paper. First, cooperation between Europe and China: is it short term, long-term, or strategic? Many agreements have been designed and signed, but both bureaucracies and multiplying EU crises have somewhat prevented a faster development. Second, the future of European infrastructures: There are technical aspects that involve the protection of local industries and environmental laws. Third, the impact of national elections on government decision-making: They can be quite radical, and more dramatic changes could take place in the years to come. Fourth, tensions between elites and grassroots views. There is a sense that decisions on allowing Chinese FDIs are sometimes “made by elites” against the will of the people, and not necessarily to the benefit of the latter. Sixth, human resources: Job creation remains the top priority of all the decision-makers in Europe. As explained in the COSCO/Piraeus case, Chinese investors have been better perceived when using local staff.

Most of these issues can be applied to future projects under the BR. If China is to lead through this new initiative, it is implied that it should develop a sense of universality, or at least an understanding of the political, social, cultural, and economic environments where it is intending to invest. Central Asian countries, for example, have a relatively short history as independent nations, but they have the same sense of belonging and history as any other country. Therefore, the BR will have to encompass local aspects as much as global aspects, financial sustainability, transparency, and local political systems.

The internationalization of China, and of its companies in particular, is one of the most important phenomena of the beginning of the twenty-first century. After taking an interest in Africa, Oceania, and Latin America, China has started looking at developed countries, where it engaged in some increasingly important investments. Each of the European countries possesses a sophisticated legal apparatus inherited from its history. The legislation of the European Union adds still another layer of complexity. However, if they want to be engaged over the long term, potential Chinese investors will have no other choice but to understand and accept this system.

Now that China is engaged in a major initiative that will give it responsibilities not just towards its own people, but also towards the foreign populations in countries where it is investing, it is hoped that Beijing’s decisions will not be oriented exclusively towards its domestic public opinion, especially when acquiring European technological jewels, or even utilities. Moreover, promises of Chinese infrastructure projects directed at Central Asia, Pakistan, and even Europe must be followed by actual deeds. In too many cases, announcements of cooperation have been made without them becoming reality.

Please click to read full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

In order to capitalise on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Henan’s Zhengzhou city is looking to develop itself into one of central China’s modern comprehensive transportation and logistics hubs, a role for which it is ideally situated. More than 90% of China’s population, as well as the regions, including China’s three principal industrial zones – the Bohai Rim, Yangtze River Delta and Pearl River Delta – that produce 95%-plus of its GDP – can be reached by air in just two hours. At present, the city is expanding its airport in a bid to be an integral part of the Air Silk Road, while its connection to the China-Europe Railway Express (CR Express) network has also enhanced its logistics offer.

Over recent years, Zhengzhou has been refining its air transport system. In line with this, the Zhengzhou Airport Comprehensive Economic Experimental Zone was established in 2013 as a means of improving Zhengzhou’s aviation logistics and attracting more advanced manufacturing and modern service companies, which typically rely heavily on airport facilities, to the city. Zhengzhou Airport has also been rapidly expanding its links with the world’s other major airline hubs.

The Henan government rolled out the Work Plan for the Construction of the Zhengzhou-Luxembourg Air Silk Road in September 2017, with Luxembourg, which lies at the heart of Europe, identified as the first connection point for the Air Silk Road. Now the Zhengzhou-Luxembourg link is in place, their coordinated development as a dual hub should help Zhengzhou achieve its goal of becoming an international aviation logistics centre.

Airport Experimental Zone

Zhengzhou has been expanding its airport over recent years, with the establishment of the Airport Comprehensive Economic Experimental Zone having laid a good foundation for the Zhengzhou-Luxembourg Air Silk Road. Back in 2013, local municipal government launched China’s first national-level airport economic experimental zone with Zhengzhou Xinzheng International Airport at its core.

Although the experimental zone is outside the China (Henan) Pilot Free Trade Zone (FTZ), it is intended that the two develop jointly in the hope that this will help improve international transportation and logistics channels. The zone has a planned area of 415 sq km and is divided into four functional sub-zones – the Zhengzhou Airport Core Area, an Urban Comprehensive Service Zone, an airport-based Exhibition and Trading Zone and an Advanced Manufacturing Cluster.

The Airport Experimental Zone, itself, is designed to be an international aviation logistics centre. The plan is to improve its land and air distribution networks and enhance China’s freight transit and distribution capability by linking up with the world’s major airline hubs and aviation logistics channels. A modern industrial base of aviation logistics, advanced manufacturing and modern services is also being built, with the airport-based economy in the driving seat. Ultimately, the zone will open up its aviation services and promote the innovative development of the inland port economy in a bid to establish Zhengzhou as a modern aviation city.

Aviation Integration

The Zhengzhou Xinzheng Comprehensive Bonded Zone plays a particularly important role in the development of Zhengzhou as an aviation hub. It is one of China’s 13 comprehensive bonded zones and the first in Central China. It began operations at the end of 2011 and has four major functions – bonded processing, bonded logistics, port operations and comprehensive services.

In order to speed up the development of Zhengzhou as an airline hub, the Xinzheng Comprehensive Bonded Zone has linked up with Zhengzhou Airport, integrating the operations of the bonded zone and the airport. The Xinzheng Comprehensive Bonded Zone established the Port Operations Centre in 2015, which officially began operating in early 2016. All customs clearance procedures and formalities, including customs declaration, inspection and acceptance, are carried out in this centre which operates around the clock. Currently, about 3,500 trucks enter or leave the centre every day.

Although the Xinzheng Comprehensive Bonded Zone and Zhengzhou Airport are less than 3km apart, they have their own customs offices which operate independently. Before the establishment of the Port Operations Centre, goods exported through the Xinzheng Comprehensive Bonded Zone had to clear customs first in the bonded zone and then at the airport. All customs clearance procedures had to be done twice. Since the establishment of the Port Operations Centre, all cargoes entering or leaving the bonded zone go through this centre. Because the customs clearance system is now integrated, cargoes passing through the bonded zone and the airport only need to undergo customs clearance and inspection once. This simplified procedure greatly cuts customs clearance time, from three hours to about 40 minutes. The new practice not only saves time but also reduces logistics cost.

The Airport Experimental Zone has also introduced measures to help businesses. In 2017, Zhengzhou attracted the leading fashion brand Zara to settle in the Xinzheng Comprehensive Bonded Zone, establishing it as Zara’s distribution centre in China. Staff at the Airport Experimental Zone specially designed simple and convenient customs clearance procedures for Zara, creating a system that allows goods to enter before a customs declaration is made. Zara now ships all garments bound for the China market to Zhengzhou, where they are sent by trucks to the Port Operations Centre within the Xinzheng Comprehensive Bonded Zone after being offloaded from cargo planes. After sorting and customs declaration, the garments are directly delivered to Zara’s 300 stores in 20 cities across the mainland, including Chongqing, Chengdu and Xi’an. This model of logistics and distribution is convenient and time-saving, allowing distribution to begin just a few hours after the goods arrive at the Port Operations Centre. The model is expected to become standard practice, and should help Zhengzhou develop into a major distribution centre in the Asia-Pacific region.

Taiwan-funded Foxconn Group has also set up a factory in the Xinzheng Comprehensive Bonded Zone to make iPhones and provide after-sale repair and testing services to users worldwide. Foxconn unveiled plans to move its Hong Kong warehouse to the mainland in 2015. iPhones awaiting repair from around the world are no longer sent to the transit warehouse in Hong Kong before shipment to Zhengzhou. Instead, they are sent straight to the Xinzheng Comprehensive Bonded Zone. This has reduced the time it takes for phones to arrive in Zhengzhou from more than 20 days to just two weeks. The Airport Experimental Zone boasts a complete mobile phone industry chain that covers phone production, manufacture of core components and parts, and maintenance service. It produced nearly 300 million smartphones in 2017, over one-seventh of the global output. It is the world’s largest Apple iPhone production base, making Zhengzhou an important manufacturing base for smart devices.

Cross-Border E-Commerce: Integrated Development of Transportation and Trade Zhengzhou is committed to developing multimodal transportation and improving its logistics networks in the hope that transportation will boost trade and trade will in turn spur the growth of logistics. Cross-border e-commerce is a form of trade that relies heavily on an efficient logistics chain and is crucial for the integrated development of transportation and trade. In view of the importance of cross-border e-commerce, the Xinzheng Comprehensive Bonded Zone set up the “Cross-Border E-Commerce Crowd-Innovation Incubator” within the zone. More than 80 cross-border e-commerce companies, including Tmall.HK, JD.com and Cainiao, have established a presence here. Cross-border e-commerce in the bonded zone is mainly export-oriented. The Henan Bonded Logistics Centre within the Zhengzhou Jingkai Comprehensive Bonded Zone is the largest such centre dealing with imports. Cosmetics and maternity and child products are the main product categories in this field. Besides improving its logistics facilities, Zhengzhou also tries to boost the development of cross-border e-commerce at retail level. The Airport Experimental Zone and the Henan Bonded Logistics Centre both have bonded direct purchase centres where bonded imports are displayed and sold to consumers. These centres operate on the “bonded direct purchase” model. Consumers purchase the goods directly from importers and tax is only paid after the goods are sold. As well as allowing consumers to buy imported goods at cheaper prices, bonded direct purchase centres also provide an offline display platform for cross-border e-commerce businesses and make their operation more flexible. |

The Zhengzhou-Luxembourg Air Silk Road

As its airport gradually develops, Zhengzhou is looking to enhance its role as an important gateway by increasing its links with international logistics hubs. The city government unveiled the Work Plan for Building the Zhengzhou-Luxembourg Air Silk Road in 2017, identifying Luxembourg as Zhengzhou’s first connecting point along the Air Silk Road.

Zhengzhou is the starting point for the Air Silk Road. Zhengzhou Airport is one of China’s eight major air transport hubs, with an air cargo throughput of 500,000 tonnes in 2017, according to figures from the Civil Aviation Administration of China. That was an increase of 10% from 2016, making Zhengzhou the seventh most important for cargo of China’s 229 civilian airports and the leading cargo airport in central China. Passenger traffic exceeded 24 million, up 17% from 2016, moving the airport to 13th in the rankings among mainland cities.

Luxembourg, at the other end of the Air Silk Road, lies at the heart of Europe, next to Germany, France and Belgium. Like Zhengzhou, it enjoys natural geographical advantages, with four major financial centres (London, Paris, Frankfurt and Zurich) in close proximity. Luxembourg Airport, the sixth largest air cargo terminal in Europe, had an air cargo throughput of over 930,000 tonnes in 2017, a year-on-year increase of 14%. In the same year, passenger traffic reached 3.6 million, an increase of nearly 20% from 2016.

To try to leverage the geographical advantages of both places, Zhengzhou has over the past few years been promoting the coordinated development of the two logistics hubs under the “Dual Hub” strategy. In 2014, Henan Civil Aviation and Investment Co purchased a 35% stake in Cargolux Airlines International, which operates the biggest all-cargo airline at Luxembourg Airport. Cargolux is the world’s sixth largest air freighter, and the biggest in Europe, with routes covering all parts of the world. Zhengzhou and Luxembourg airports are working together to increase the number of flights between the two cities in a bid to build an international air cargo network, with Zhengzhou as the Asia-Pacific logistics centre and Luxembourg as the logistics centre for Europe and America.

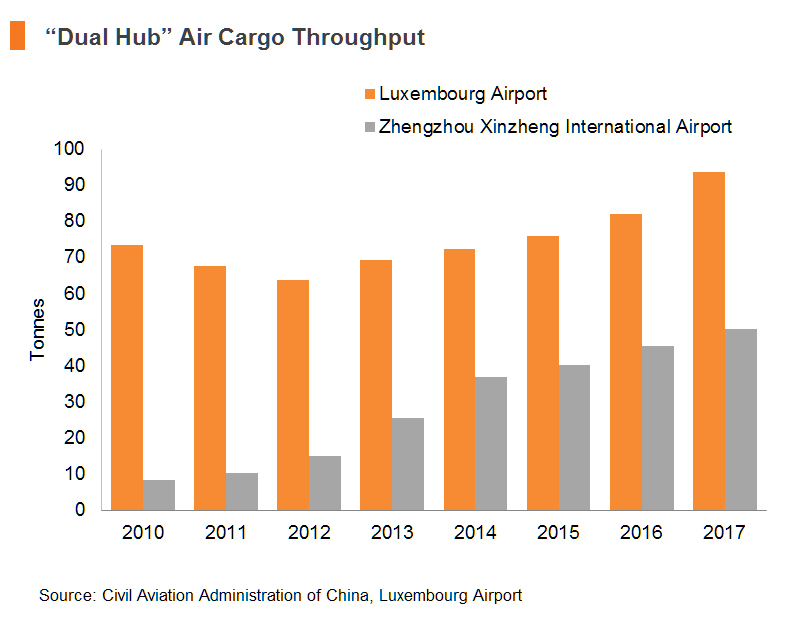

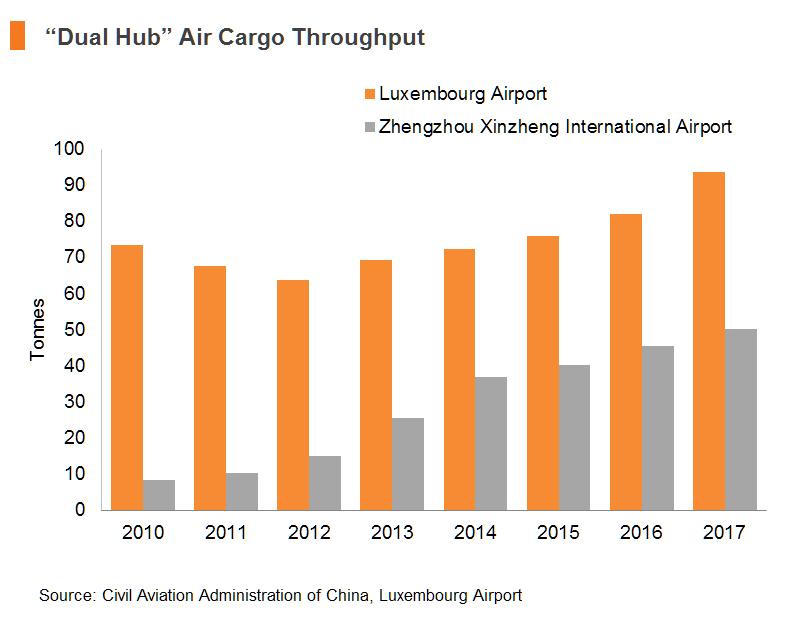

The “Dual Hub” effect has increased the frequency and volume of freight traffic between Zhengzhou and Luxembourg. The Zhengzhou-Luxembourg international air cargo route officially opened in June 2014. Early on, there was just one cargo flight per week, but that increased to six flights per week by the end of 2014, and to 16 by 2017. Air cargo volume soared from 14,700 tonnes in 2014 to 147,000 tonnes three years later, by which time it accounted for nearly a third of the total cargo throughput of Zhengzhou Airport. The air cargo throughput of both Zhengzhou Airport and Luxembourg has grown steadily over the past few years.

Zhengzhou is also expanding its air transport network. Last year, Zhengzhou Airport launched 57 new air routes, 10 of which were cargo routes. That brings its total number of cargo routes to 34, 29 of which are international ones. It has service links with 17 of the world’s top 30 air cargo hubs and now ranks fifth in the country in terms of the number of air cargo airlines, freight routes, destinations, all-cargo freighter capacity and number of flights. Zhengzhou-Luxembourg passenger flights are expected to begin operating before the end of this year.

Zhengzhou plans to continue strengthening collaboration under the Zhengzhou-Luxembourg Air Silk Road. In 2018, Zhengzhou Airport will increase its international air cargo flights and improve its flight network with an emphasis on connecting with the world’s major airline hubs. In terms of air cargo and airmail throughput, Zhengzhou Airport aims to reach 550,000 tonnes before the end of this year and exceed 1 million tonnes by 2020, with international air cargo accounting for 60% of that total. The airport will also start its phase three expansion with a special section for Cargolux and its member companies. The Zhengzhou-Luxembourg Air Silk Road is expected to help develop Zhengzhou as an international aviation logistics centre and create more opportunities for the logistics sector.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Dr Jonathan Choi, Chairman, CGCC

The 19th National Congress explicitly supports the integration of Hong Kong and Macao into the overall national development, with focus on developing the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Bay Area. President Xi Jinping even visited Hong Kong last year and witnessed the signing of the Framework Agreement on Deepening Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Cooperation in the Development of the Bay Area between the NDRC and the governments of the three places. This fully shows that the Central Government attaches great importance to the future development of the three places.

As an international financial and business center, Hong Kong can play a key role in the specific plans for the Bay Area. This year, I made a number of proposals to the CPPCC on how to make the best use of Hong Kong’s strengths to develop the Bay Area into an important hub for the country’s sustained and diversified economic development.

Develop LMC Corridor

The governments of Hong Kong and Shenzhen have inked a deal to jointly develop the Lok Ma Chau Loop (the “LMC Loop”) into an innovation and technology (I&T) park. Located at the border between the two places, the park is an important base for I&T development in the Bay Area. I suggested including some areas along Shenzhen River’s banks adjacent to the LMC Loop and transform the Futian Bonded Zone into a logistics and incubation base for technology industries to further expand the LMC Loop to form an innovation corridor, developing the Bay Area into a national I&T, R&D and application center.

Hong Kong and Shenzhen can consider setting up an administration bureau to formulate specific division of work in the LMC Loop, introduce arrangements to facilitate movement of technology and authorized personnel in and out of the area, cancel restrictions on cross-border research funding and exempt customs duties on imported scientific research equipment in order to lay a good foundation for I&T development in the Bay Area.

Support development of free-trade ports

The 19th National Congress report also mentioned considering developing free-trade ports. As a special economic zone with the world’s highest standard, Hong Kong’s strengths can be an important reference for the development of free trade ports in the Bay Area. The Central Government can explore using Hong Kong as a blueprint to support the upgrading of the Qianhai, Nansha and Hengqin free trade areas into free trade ports, strengthen the free flows of foreign trade, funds and talents including those from Hong Kong and Macao so as to facilitate the presence of talented people from Hong Kong and the rest of the world, and consider emulating Hong Kong in terms of tax structure and preferential treatment.

The authorities can also explore setting up onshore and offshore RMB centers in the Qianhai and Nansha free trade ports and work together with Hong Kong to broaden the two-way offshore RMB channel to attract more mainstream and emerging financial institutions from Hong Kong. For trade facilitation, policy arrangements can be made for exemption of import and export tariffs, and to attract more domestic and foreign enterprises, provide a convenient, standardized and efficient management system and business environment, and in particular support Hong Kong businesses in getting national treatment to access the relevant markets.

State-level leader to oversee development

To effectively implement the Bay Area’s development plan and enable it to play a key role in national economic development, it is necessary for the Central Government to formally incorporate it into its national development strategy. Since Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macao have different social and economic systems and are independent customs duty zones, and their key government officials are very highly ranked, it is better for the Central Government to set up a coordinating committee for the Bay Area. The committee should be headed by a state-level senior leader to supervise the implementation of the overall development plan. It should also coordinate with the NDRC, the relevant central ministries and the governments of the three places for research decisions on major cooperation issues and coordinate specific implementation tasks for integration among the cities in order to avoid duplication.

In fact, CGCC and Hong Kong’s industrial and business community earnestly look forward to the implementation of the Bay Area’s development plan, which will provide enormous new opportunities for Hong Kong businesses. We will actively facilitate stronger ties among entrepreneurs, chambers of commerce and industrial and business groups of the three places through a business cooperation platform, explore how to assist businesses to more effectively participate in the Bay Area’s development, and maintain close contact with relevant government departments to pass on the feedback of the business community, providing businesses with broad support in capturing opportunities in the area.

This article was first published in the magazine CGCC Vision March 2018 issue. Please click to read the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Linda Lim, Professor of International Economic Relations 2018 at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Relations (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Synopsis

Despite its growing prominence internationally, China’s Belt-and-Road Initiative (BRI) is facing a host of challenges. Unless these are addressed, Beijing will find the BRI ending up more a nightmare than a bonanza.

Commentary

XI JINPING’S signature Belt-and-Road Initiative, BRI (which the rest of the world still calls One-Belt-One-Road or OBOR) has attracted a great deal of global attention. The United States and some European Union countries are apprehensive that BRI signals China’s attempt to dominate the two-thirds of the world’s population, and 40 percent of global trade, accounted for by BRI countries.

BRI links China with faster-growing emerging markets, providing an alternative to slow-growing, increasingly protectionist Western markets, and outlets for its abundant domestic savings and industrial excess capacity. Developing infrastructure and relationships in BRI countries will help private and state companies venturing abroad, where they will learn to compete internationally and thus “become stronger”, while also moving China “closer to (the world’s) centre stage”, as President Xi wishes.

Challenge of Infrastructure Play

But funding infrastructure projects is always a challenge. They are large, capitalintensive and expensive, with long construction and payback periods, thus involving high risk. They are also characterised by externalities or spillovers: because social exceed private costs and benefits, left to private investors there will be underinvestment.

Because of this, public funding is the most common funding model for infrastructure projects. Governments can borrow at lower cost than private entities, given an implicit sovereign guarantee against default. They have a longer time-horizon, and investing to prioritise social benefits in instances of “market failure” is their responsibility.

Consortia are also a popular model, involving public-private partnerships, and multilateral and regional agencies, such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Consortia can raise more capital and obtain more expertise from diverse multiple sources, and reduce the risk for any individual lender/investor as well as the borrower/project.

In developing countries capital is scarce, so at a premium, while borrowing from cheaper foreign sources requires repayment in foreign exchange, adding currency risk. Governance risk arises from governments often lacking the expertise to evaluate, implement and monitor projects, and leakage through corruption is common, increasing cost, delay and quality problems.

Political and Other Risks

There is also political risk, since the distribution of costs and benefits may not be equitable, and social unrest may result from disputes over land appropriation and compensation, labour, and environmental consequences such as harm to local

farming, forests and fisheries. Authoritarian governments are not transparent, and may use coercion to resolve disputes, while democratic governments may change and demand changed terms.

BRI countries pose additional high country risks. Many are low-income so lack capital, human resources, and capacity to earn export revenues to pay for imports of materials and equipment for BRI projects, posing high risks of debt and currency crisis. There may be domestic political or economic turmoil, unstable or unpopular governments, and contentious relations with neighbours sharing or affected by projects like dams.

A recent study by the Centre for Global Development identified eight countries (Djibouti, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Maldives, Mongolia, Pakistan, Montenegro, Tajikistan) where the immediate marginal impact of BRI projects in the lending pipeline would raise their debt-to-GDP and debt-to-China ratios to “high risk” levels.

Even without such debt concerns, China’s eagerness for infrastructure projects in BRI countries may not mesh with perceived local needs and could heighten political risk for host governments who collaborate with them.

For example, in relatively developed Malaysia, one business person I interviewed said: “Most of the OBOR initiatives in Malaysia are not positive for the country. The large infrastructure projects like railways and ports are strategic for China but will be white elephants for Malaysia. The deal terms are poorly contrived for Malaysia. But Malaysia only has itself to blame for letting its politicians make such deals.”

Chinese Business Model

The preferred Chinese infrastructure business model does not help win local support, based as it is on exporting Chinese equipment, materials, management and labour to the recipient country so there is minimal local content, job creation, training and supplier linkages. This adds to the perception that BRI projects are for China’s rather than host countries’ benefit.

As another business respondent put it: “The Chinese are relentless in pursuit of profit/advantage without considering negative implications for local communities.” Chinese companies have been accused of poor business practices, such as undercutting local suppliers, failing to honour contracts and to comply with local regulations, while delivering inferior quality and reliability, such as plagued Chinesebuilt power plants in Indonesia.

Another business person familiar with BRI projects told me: “Big Chinese companies are unfamiliar with private enterprise and market economies, because they are all linked to the Chinese government and follow a top-down mode of operation. They are comfortable only with G2G deals.”

Chinese companies’ preference for working through local political leaders, rather than directly with communities affected by their projects, may mean that project social costs are not adequately calculated and compensated for. This results in protests which can stall projects, as has happened with the Myitsone dam and Kunming-Kyaukphyu railway and oil-and-gas pipeline in Myanmar.

If the local leaders China works with are incompetent, corrupt, greedy or unpopular, this rubs off on them, while dissatisfaction with Chinese projects can rub off on the local leaders who collaborate with them — in both cases, heightening political risk.

China’s Creeping Arrogance

In Sri Lanka, the government’s leasing Hambantota port to a Chinese state-owned company in payment of debts incurred for its construction contributed to its local electoral losses in February 2018. And in Indonesia, there are rumours that President Jokowi’s encouragement of Chinese investments could undermine his prospects for reelection in 2019.

Chinese companies also lack experience operating in ethnically and culturally diverse countries, and are frequently accused of lacking respect for local practices and customs, such as observation of Muslim prayer times and the fasting month. They

show no interest in learning about or understanding local populations (or eating their food), displaying what one of my respondents called “unconscious arrogance due to their superior feeling of the success of China”.

This can backfire on local ethnic Chinese populations in Southeast Asia, who already dominate business in some countries, are favoured as local partners by Chinese companies, and would be resented if seen to benefit disproportionately from China investments. Other local Chinese worry that the unpopularity of high-profile Chinese projects could exacerbate latent anti-Chinese feelings that could adversely affect them.

What Can China Do to Correct Image?

What can China do to counter these destabilising negative perceptions of BRI projects?

First, Chinese companies should undertake only projects which are financially, economically and politically viable, and environmentally and socially sustainable. Including such calculations means many projects will not make the cut. Second, they should partner with other lenders and investors, from different countries. Diversification reduces risk, and dilutes the image of being Chinese.

Third, they should make investment decisions together with the host country, not unilaterally, to ensure that the projects are “mutually advantageous” as claimed. Fourth, they can help recipient countries to repay their loans by earning foreign

exchange, for example, by establishing industrial zones for companies relocating labour-intensive manufacturing from China, and by developing markets in China for their exports.

Fifth, they should employ better public relations. This includes being transparent and communicating with local media and host communities about project rationales. And they should reduce high visibility ̶ opening ceremonies should include other foreign partners and investors as well as more locals, and projects should be “branded” not as “Chinese” but as “national” projects, to reduce fears of a loss of sovereignty.

Sixth, they should employ locals as labour and management, provide technical and skills training, and work with all stakeholders, not just the government or party-inpower. In addition, they should train, encourage and expect their Chinese employees to understand, respect and engage with local cultures. All this requires fundamental changes in corporate culture and business model.

Be ‘Less Chinese’

In short, to be successful, BRI projects should become less Chinese. While this might seem to run counter to China’s hope for “soft power”, the billions invested will otherwise not deliver, and may even undermine, its foreign policy goals.

Today, with a massive US$57 billion investment in energy and infrastructure projects in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, the Pakistan government has to employ a 15,000-strong military force to protect Chinese workers. Despite this, in February 2018, a Chinese shipping executive was shot dead in his car in Karachi in “a targeted attack”. If China does not learn to adapt to life outside the Great Wall, the Belt-and-Road Initiative risks turning into a foreign policy nightmare, not a bonanza.

Please click to read full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

中國外經貿企業服務網

習近平總書記在2013年訪問中亞四國和東盟期間,先後提出了"絲綢之路經濟帶"和"海上絲綢之路"的戰略構想,並在2013年12月召開的黨的十八屆三中全會上通過的《中共中央關於全面深化改革若干重大問題的決定》關於“構建開放型經濟新體制”中進一步明確提出:"加快同周邊國家和區域基礎設施互聯互通建設,推進絲綢之路經濟帶、海上絲綢之路建設,形成全方位開放新格局。""一帶一路"倡議的提出,是時代的要求,是把快速發展的中國經濟同沿線國家利益結合起來,利用中國自身發展優勢實現自身發展的同時,帶動其他國家乃至世界經濟發展的偉大創舉。

亞洲開發銀行(簡稱"亞開行")在2014年發佈的《亞洲發展展望報告》裡面指出,雖然亞洲區域的經濟增長速度有所放緩,但其仍然是全球主要國家中增速最快的區域,尤其是該區域主要經濟體正在執行的改革措施將繼續推動該區域領銜全球經濟增長,因此亞洲區域是實行"一帶一路"倡議的重點。

經濟的快速發展需要相應的配套設施,然而目前亞洲國家在基礎設施上依然存在巨大的不足。根據亞開行的預測,2010-2020年亞太地區對基礎設施的需求高達8萬億美元。基礎設施的建設是支持經濟發展的重要保障,也是實現"一帶一路"倡議互聯互通的基本要求,而基礎設施的建設需要巨額資金的支持。

"一帶一路"倡議實施過程中的資金需求主要集中在以下幾個領域:一是通信、供水和環衛設施等基礎設施領域。沿線的中亞、東南亞等國家的基礎設施較為落後,對基礎設施的新增需求強烈。二是交通、港口等跨境通道領域。"一帶一路"的暢通需要提升鐵路、公路、管道等通道能力。三是能源、資源領域。"一帶一路"跨越的地區能源和資源豐富,特別是中亞、俄羅斯等地區蘊藏著豐富的礦產、石油、天然氣等資源,開發潛力巨大。"一帶一路"沿線國家雖然經濟發展迅速,但是差異較大,一些國家市場制度不完善,在這些國家進行基礎設施建設,存在資金需求量大,投資回報期長而且未來收益不確定的問題。與此同時,"一帶一路"沿線國家間目前跨境金融合作的層次較低,大部分的貸款集中在油氣資源開發,管道運輸等能源領域,其他領域未能從中受益。因此,為了順利推進"一帶一路"倡議的實施,為"一帶一路"沿線特別是亞洲區域的基礎設施建設提供資金支持,我們需要對融資進行總體的規劃,構建以絲路基金為引導,以亞洲基礎設施投資銀行等國際開發性金融機構為重要支撐,以國內政策性銀行、國內商業銀行以及民間投資機構為主要基礎的多元聯動的融資機制。

充分發揮絲路基金的引導作用

2014年11月,在加強互聯互通夥伴關係對話會上,習近平總書記發表了《聯通引領發展夥伴聚焦合作》的重要講話:中國將出資400億美元成立絲路基金。絲路基金成立的初衷是為“一帶一路”服務,主要使命是為"一帶一路"沿線國家提供基礎設施建設、資源開發、產業合作等有關項目提供投融資支持。絲路基金是一個開放的平臺,它的包容性和多元化可以為"一帶一路"倡議實施提供豐富的融資渠道和方式,可以吸引有資金實力、有知識和管理經驗的銀行和投資機構參與,多方彙聚就可以優勢互補,博採眾長。絲路基金的定位是中長期的開發投資基金,注重合作項目,更注重中長期的效益和回報。不同於以往股權投資7~10年的投資週期,絲路基金的投資期限能夠到15年或者更長的時間,可以滿足一些發展中國家中長期的基礎設施建設的資金需求。絲路基金首期資本金100億美元(首期注入的資本為美元),這主要是便於國內外投資者通過市場化方式加入進來,外匯儲備通過其投資平臺出資65億美元,中國投資有限公司、中國進出口銀行、國家開發銀行亦分別出資15億、15億和5億美元。隨著"一帶一路"倡議的不斷推進,相信會有更多的資本進入。

2015年4月20日,絲路基金、三峽集團及巴基斯坦私營電力和基礎設施委員會在伊斯蘭堡共同簽署了《關於聯合開發巴基斯坦水電項目的諒解合作備忘錄》(以下簡稱《諒解備忘錄》),該項目是絲路基金註冊成立後投資的首個項目。根據《諒解備忘錄》,絲路基金將投資入股由三峽集團控股的三峽南亞公司,為巴基斯坦清潔能源開發、包括該公司的首個水電項目——吉拉姆河卡洛特水電項目提供資金支持。電力行業是巴基斯坦政府未來十年發展規劃中優先支持的投資領域,絲路基金首個對外投資項目落地巴基斯坦的電力項目,標誌著絲路基金開展實質性投資運作邁出了重要一步,而"中巴經濟走廊"建設是"一帶一路"建設的旗艦,表明絲路基金服務"一帶一路"建設的使命。從項目運營管理模式來看,卡洛特水電站計劃採用"建設—經營—轉讓"(BOT)模式運作,於2015年底開工建設,2020年投入運營,運營期30年,到期後無償轉讓給巴基斯坦政府;從項目融資方式來看,絲路基金投資卡洛特水電站,採取的是股權加債權的方式:一是投資三峽南亞公司部分股權,為項目提供資本金支持。在該項目中,絲路基金和世界銀行下屬的國際金融公司同為三峽南亞公司股東;二是由中國進出口銀行牽頭並與國家開發銀行、國際金融公司組成銀團,向項目提供貸款資金支持;從控制風險方面來看,通過股權加債權的方式,一方面可以通過股權鎖定長期投資的高額回報,獲取一定股份,參與公司治理,提高投資收益的確定性,另一方面可以通過債權獲取優先清償權,有助於控制風險。絲路基金不是援助性的,在一定程度上也是逐利的,因此絲路基金在服務"一帶一路"建設的同時要評估項目的風險,平衡好風險和收益之間的關係。

然而,就絲路基金目前的設計規模來看,即使不斷加入新的投融資機構,其資金也難以滿足"一帶一路"沿線上萬億基礎設施建設的資金需求,因此我們有必要充分發揮絲路基金的引導作用,為國際開發性金融機構以及國內政策性銀行、國內商業銀行以及民間投資機構等投資指引方向,通過不同方式吸納調動各方資金,服務"一帶一路"建設。

絲路基金的資金是政策性質,象徵性和號召力較強,因此當絲路基金決定投資某一項目時,就為外界傳遞一種積極的信號,這時商業資本的逐利性和風險規避性決定了當其發現這一項目有政府保障而且有利可圖的時候,商業資本就會參與項目投資,這樣就可以吸引國際金融機構以及商業性金融機構參與進來。絲路基金還可以通過吸納境內外資金支持戰略開發項目,充分依託政府信用,向境內外金融市場發行“一帶一路”倡議專項債券,引導外匯儲備、社保、保險、主權財富基金等參與"一帶一路"投資。

充分認識國內政策性和商業性銀行以及投資機構的基礎作用

"一帶一路"沿線國家數目眾多,在這些國家進行基礎設施建設不僅需要巨大的資金,而且需要有專門的海外項目投融資的知識和經驗。

國內政策性銀行的資金為政策性質,國家信用擔保,並且本身資金實力雄厚,可以對大型、長期的項目提供融資服務。雖然政策性銀行的境外服務網絡不多,但是其合作代理行較多,因此可以通過信貸產品的發行為"一帶一路"融資服務。如2014年中國進出口銀行對"一帶一路"周邊29個國家累計貸款超過1200億美元,其中向巴基斯坦的能源和基礎設施領域提供了約8億美元融資支持,隨後還將為其提供多達十億美元的融資支持,這可以有力的促進巴基斯坦基礎設施建設,推進"一帶一路"倡議的順利實施。2014年,國家開發銀行向"一帶一路"周邊29個國家累計貸款超過1200億美元,目前國家開發銀行已與世界69個國家和地區的100多家區域、次區域金融機構建立了合作關係,在中長期投融資方面具有顯著優勢,可以為"一帶一路"基礎設施的建設提供有益支持。除了本身的項目貸款,中國進出口銀行和國家開發銀行還應該積極的支持有實力的中國企業"走出去",為企業開展對外投資提供貸款支持,幫助企業進行項目的建設融資。

商業銀行的信用較好,籌資能力較強,對於"一帶一路"中的一些大型項目可以採取銀團貸款的方式為其提供融資服務,也可以利用自身境外網點眾多,牌照比較齊全等優勢,為"一帶一路"各種項目和各個企業提供各種金融服務,如可以利用人民幣發放境外貸款降低融資成本或者也可以在離岸市場開發新的避險產品,幫助境外企業降低匯兌風險。因此我們要積極發揮商業銀行在"一帶一路"倡議實施中的重要作用。2015年,中國銀行將為"一帶一路"相關項目提供不低於200億美元的授信支持,而中國建設銀行也已確立相關項目資金需求約2000億元。中國工商銀行借助其境外網絡優勢,如今已經在"一帶一路"沿線的18個國家和地區擁有120家分支機搆,並與700多家銀行建立了代理行關係,其在2014年支持的"一帶一路"境外項目已達到73個,總金額達109億美元,業務遍及33個"一帶一路"沿線國家,而且目前中國工商銀行已經儲備了131個"一帶一路"的重大項目,支持項目投資額高達1588億美元,涉及電力、交通、油氣、礦產、電信、機械、園區建設、農業等行業,基本實現了對"走出去"重點行業的全面覆蓋。

中國投資有限公司(簡稱"中投")是中國最大的主權財富基金,在絲路基金首期資本金100億美元中,中投出資15億美元,超過進出口銀行和國家開發銀行的出資額。中投在很大程度上代表著"國家角色",在全球資本佈局、海外商業網絡等多方面擁有獨特優勢,推進"一帶一路"建設,要積極發揮中國投資有限公司的重要作用。

另外,我們還要積極鼓勵民間的投資機構走出去進行海外投資,為"一帶一路"建設添磚加瓦。目前中國最大的民營投資集團是中國民生投資股份有限公司(簡稱"中民投"),註冊資本500億元人民幣,由中國59家知名的民營企業發起成立,參股股東均為大型民營企業。2015年3月27日,中民投宣佈將帶領數十家國內優勢產業龍頭民營企業,共同在印度尼西亞投資50億美元建設中民投印尼產業園,且投資規模短期內將超過百億美元,主要包括鋼鐵在內的水泥、鎳礦、港口等四大產業項目,這是中民投貫徹落實"一帶一路"國家倡議、踐行企業國際化的最新舉措。民營企業在技術、管理、工藝等方面都具有比較大的優勢,但是相比政府背景的銀行和機構來說,抵禦風險的能力較低,因此他們在選擇投資項目時會事先對其進行詳細的考察、論證,在形成一套比較成熟的投資方案之後才會最終確定投資方案。這樣就可以保證確定的項目在一定時間內基本上都能順利完成,減少爛尾風險,可以有效的推進"一帶一路"倡議的實施。

我們應該摒棄以往參與跨國基礎設施援助項目和部分工程承包項目中"政府主導"的觀念,以更加"市場化"的運作推動基礎設施建設。因此要鼓勵民間資本參與"一帶一路"信貸項目,加快政府和社會資本合作的步伐,創新公私合營模式(Public-Private Partnership,簡稱PPP模式)。通過PPP模式既可以在不過度增加財政負擔和不加稅的情況下改善一國基礎設施建設並提供公共服務的能力,也可以有效的"撬動"私營資本參與基礎設施建設,所以在推進"一帶一路"倡議實施中涉及到的能源、水和汙水處理、運輸和通訊等部門可充分發揮PPP模式的作用。

綜上所述,助力"一帶一路"倡議實施的各個資金提供機構之間不是各自為戰、相互競爭的關係,而是相互合作、協同發展的關係。為了推進項目融資的有效進行,我們要形成多方聯動的融資機制。"一帶一路"建設中的一般項目都需要債權融資和股權融資相配合,在充分發揮絲路基金的引導作用的基礎上,由絲路基金聯合其他投資機構比如亞投行共同投資股權,中投也可以附加參與一部分股權投資,啟動一些本來因缺少資本金而難於獲得貸款的項目,然後由中國進出口銀行和國家開發銀行跟進發放貸款,由商業銀行為項目參與企業提供銀行業務,積極引進民間資本參與項目建設,多方聯動,共同促進項目實施,有力的推動"一帶一路"倡議的實施。

請按此閱覽原文。

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Jan Gaspers, Head of the European China Policy Unit, Mercator Institute for China Studies

Nowhere else in Europe has China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) been met with quite such a warm embrace as in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). China’s large-scale financing of highways, railways, ports, and other infrastructure to better connect China to Southeast Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Europe has clearly struck a chord with CEE leaders.

This is hardly surprising. Almost three decades after the end of the Cold War, the CEE region still displays a remarkable infrastructure gap. Estimates from July 2017 suggest that shortages in transport infrastructure financing alone in CEE and CIS countries will amount to $730 billion up to 2025. Rather conveniently, China has pledged about $15 billion in investments in CEE infrastructure since the launch of the so-called “16+1” platform in 2012. Made up of 11 EU member states (Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia), 5 EU neighbourhood countries (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia), and China, the 16+1 platform has become a primary venue for economic and political dialogue.

Cooperating more closely with China, the 16 CEE countries do not only hope for infrastructure financing but also for foreign direct investment (FDI) in a wide range of other sectors. In November 2016, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China established a €10 billion China-CEE investment cooperation fund to finance investments in sectors such as high-tech manufacturing and consumer goods. At the Budapest Summit in November 2017, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang promised that the fund would be expanded by another $1 billion and also announced that the China Development Bank would create a $2.38 billion development finance facility for CEE. In addition, China has also used bilateral channels to conclude investments deals with individual CEE countries.

However, the economic realities of Chinese engagement in CEE hardly live up to the ambitious rhetoric habitually vented at 16+1 summits. Comprising only one bridge in Serbia and one motorway in Macedonia, as of late 2017, the list of China-financed 16+1 infrastructure projects completed remains short. The few projects currently underway in the region – notably all of them in the five non-EU 16+1 countries – suffer from the same problems that have accompanied BRI projects in other parts of the world. Hence, Chinese infrastructure loans in the Balkans have been linked to Chinese contractors and suppliers performing the work, providing little stimulus to local economies. Moreover, the fiscal stability of smaller Balkan countries is at peril, as Chinese infrastructure loans and corresponding sovereign guarantees reach the level of 1/3 of national GDPs, like in the case of Macedonia.

Inside the EU, the economic picture is similarly bleak. In February 2017, the European Commission opened a formal investigation into the flagship BRI construction project in Europe, a $2.89 billion high-speed rail link between Belgrade and Budapest. At the time, Brussels expressed doubts about the financial viability of the project and its compliance with EU public procurement rules, as Budapest had failed to issue a call for public tender as is normally required for projects of such magnitude. Eventually, at the Budapest 16+1 Summit, an official call for tender for the project was issued, but, Hungary has made it clear behind closed doors with EU officials that it expects Chinese companies to win the contract. However, for now, China has little to show with EU members in CEE other than some sizeable investments in utility providers. Chinese loans for large-scale infrastructure remain rather unattractive in light of existing EU financing mechanisms, such as the EU’s structural cohesion funds, the European Fund for Strategic Investment (EFSI), or the Trans-European Transport Networks (TEN-T), which tends to partially consist of grants.

Wider Chinese FDI in Central and Eastern Europe also hardly aligns with Beijing’s ambitious rhetoric. China’s own official figures suggest that, as of June 2017, roughly $8 billion in FDI had flowed into CEE industries, including into machinery equipment manufacturing, chemicals, telecoms, and new energies. Considering the size and output of CEE economies, the investment is significant, but it pales when compared to investments in Western EU member states. Part of the reason why overall Chinese FDI in CEE remains low is that financing has been and remains concentrated in the biggest CEE EU member states and Serbia rather than spanning across the whole region. Moreover, the China-CEE investment cooperation fund seems to have failed to complete a single transaction to date.

Despite these sobering economic realities, some political elites in CEE EU member states cling to cooperation with Beijing, actively positioning closer ties with China as a counter-narrative to EU cooperation and the liberal values underpinning the European project. In a clear reference to Brussels, Hungary’s prime minister, Viktor Orban, remarked at the Budapest 16+1 Summit, “We see the Chinese president's 'One Belt, One Road' initiative as the new form of globalization, which does not divide the world into teachers and students but is based on common respect and common advantages.” During Chinese president Xi Jinping’s visit to the Czech Republic in March 2016, Czech president Milos Zeman declared on TV that his country’s poor relations with China in the past were due to the “submissive attitude of the previous government towards the U.S. and the EU” and celebrated the signing of a strategic partnership with China as “an act of national independence.”

While it is not clear whether statements like this are meant to be bargaining chips in negotiations with Brussels over national economic and political priorities or whether they reflect genuine sympathy for China’s political and economic system, the political damage Chinese investment in the CEE has created for the EU is already visible. The EU has been unable for some time to act cohesively vis-à-vis China on trademarks of EU foreign policy, namely upholding the international rule of law and protecting human rights.

In July 2016, Hungary and Greece – the latter of which is a 16+1 observer and major beneficiary of Chinese investments in recent years – fought hard in Brussels to avoid a direct reference to Beijing in an EU statement about a court ruling that struck down China’s legal claims over the South China Sea. In March 2017, Hungary derailed the EU’s consensus on signing a joint letter denouncing the reported torture of detained lawyers in China. In June 2017, Greece blocked an EU statement at the UN Human Rights Council criticizing China’s human rights record, marking the first time the EU failed to make a joint statement at the UN’s top human rights body. CEE countries have since blocked similar EU statements on China.

Considering these developments, current discussions in Brussels about creating a European investment screening mechanism, which is first and foremost geared at Chinese strategic investments in European high-tech industries, will become a litmus test for the EU’s ability to act decisively on China. Chinese investments have already prompted individual 16+1 EU members to challenge the current proposal. However, even if the EU manages to adopt the mechanism by summer 2018 – as is currently envisaged by the biggest member states – this will not help to overcome what is already a central theme in European China policymaking: a growing lack of trust between the East and the West.

Please click to read full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By UNCTAD

The governments of the Lao Peoples’ Democratic Republic, Myanmar and Liberia – among the world’s least developed – are looking to new horizons and e-commerce to boost trade and create jobs.

Each country asked UNCTAD to carry out a Rapid e-Trade Readiness Assessment to guide them in building the right “e-commerce ecosystems” and provide their policymakers with a blueprint for harnessing the economic and developmental potential offered by online trade.

The reports were showcased on the first day of e-Commerce Week on 16 April. The event was opened by UNCTAD Deputy Secretary-General Isabelle Durant and attended by Liberia’s industry and commerce minister, Wilson Tarpeh, Myanmar’s deputy commerce minister, Aung Htoo, and Ambassador Kham-Inh Khitchadeth of the Lao People's Democratic Republic.

The event was also an opportunity for ministers, donors, investors and representatives of development banks and international organisations to survey the e-commerce landscape for other developing countries.

The UNCTAD assessments for each country analysed:

- E-commerce assessments and strategy formulation

- Information and communications technology infrastructure and services

- Trade logistics and facilitation

- Access to financing

- Payment solutions

- Legal and regulatory framework

- Skills for e-commerce

“Each assessment, and this is the beauty of the exercise, includes a list of concrete recommendations for governments,” Ms. Durant said. “We know that digitalisation offers great opportunities for development. It's true, but if we refuse to see it, we will not benefit.”

Mr. Tarpeh highlighted the importance of this assessment for Liberia – the first of its kind that UNCTAD has carried out in Africa.

“When shaping the right framework for e-commerce in Liberia, at stake lies not only our innovation capacity, but also the need to repair the broken linkages between our local industries and across our country,” Mr. Tarpeh said.

“E-commerce is as much about widening our frontiers as creating much needed jobs, particularly for our youths and women-led small and medium-sized enterprises,” he said.

Compelling business case

Policy-level attention to e-commerce is increasing in all three countries, but for different reasons.

A focus on trade and private sector development in Liberia – driven by its recent accession to the World Trade Organization – has also sparked interest towards e-commerce.

Myanmar’s recent reintegration into the global trade system, its membership of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the liberalisation of key sectors including telecommunications have presented significant opportunities for the formerly isolated country.

In the Lao Democratic Peoples’ Republic, interest in e-commerce has been triggered by a drive towards services-led growth, along with the country’s integration into ASEAN and the negotiations on a Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (a free trade agreement between the 10 ASEAN states and the six states with which ASEAN has existing free trade agreements).

With its latest assessments of these two Southeast Asian countries, UNCTAD has now covered e-trade readiness of all three least developed countries in ASEAN (the other is Cambodia) and provided a major boost to these countries’ implementation of the ASEAN’s 2017-2025 Work Programme on E-Commerce.

Sweden funded the assessments for the Lao Peoples’ Democratic Republic and Myanmar, while the Liberia assessment was funded by the Enhanced Integrated Framework (EIF), a multilateral partnership.

In detail: Myanmar

Only a decade ago SIM cards cost upwards of $3,000 in Myanmar, compared to $1.50 now. This has been brought about by an expanding and highly competitive telecommunications market.

High mobile phone use (close to 100%) and smart-phone penetration of 80% offer unprecedented opportunities to use e-commerce as an economic driver.

This is apt, given the fast pace of private sector growth, but it also presents challenges – internet users heavily rely on Facebook for access to information.

Still, the move from a cash-only to a cashless society remains a long-term goal in a country where only 6% of the population has a bank account, and the use of card payments is rare.

In detail: the Lao Peoples’ Democratic Republic

The economy of the Lao Peoples’ Democratic Republic has continued to show signs of resurgence over the last several years, and there has been a noticeable shift in its economic outlook.

Interest in the digital economy is triggered by renewed focus on trade, and especially services. Technology will be an important driver.

It is also essentially a mobile-only country, meaning that 96% of the population who access internet do so on their cell phones.

However, the country is one of the most expensive in the world when it comes to using information and communications technology: it was recently ranked by International Telecommunication Union as 144 out of 166 countries for the cost of using IT and telecoms services. Unlike Myanmar and Liberia, mobile money has not yet been taken off, owing to regulatory concerns.

In detail: Liberia

In the case of Liberia, policy conversations have shifted from post-conflict reconstruction to a greater involvement in global value chains, domestic market development and, recently, the role of information and communications technologies in government and business.

The information and communications technology infrastructure has improved significantly, driven by increased competition among service providers.

Fifty percent of the population has access to a 3G signal, while approximately 17% can access a 4G signal. This means that a relatively high 20% of mobile connections can get broadband.

Driven by select firms led by young Liberians – people under the age of 24 make up more than 50% of Liberia’s population – e-commerce is fast picking up pace and regulations on e-transactions and consumer and data protection are struggling to keep pace.

Online payments options have emerged only recently and use of mobile money is gathering steam.

Please click to read full report.