Chinese Mainland

By Richard Pomfret, Professor of Economics, Adelaide University

China’s Belt and Road Initiative has the potential to extend the Eurasian Landbridge to include both the current China-Poland mainline to western Europe and a China-Istanbul mainline with spurs to the Middle East and North Africa. This column, the second in a two-part series, outlines the history of the initiative and argues that future construction on the network could be a major step towards Eurasian integration and greatly improve rail's competitiveness relative to air for time-sensitive shipments.

The Eurasian Landbridge: Linking regional value chains

In September 2013 President Xi Jinping on a Central Asian tour announced the One Belt One Road initiative and pledged over $50 billion in Chinese funding for infrastructure projects. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), mooted shortly after and officially opened in 2016, stood ready to provide funding. In May 2017, rebadged as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the initiative was officially launched at the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing, attended by representatives from more than 130 countries and 70 international organisations. At China's 19th National Congress in October 2017, the BRI was incorporated into the Chinese constitution, institutionalising its position as a foremost foreign policy goal of President Xi.

China's Belt and Road Initiative

The high profile given by China to the BRI and AIIB helped to publicise the option of overland rail service across Eurasia. However, the BRI did not create the China-Europe railway Landbridge; much was already happening and had been market-driven in both Europe and China. The most popular line, between Chongqing and Duisburg, has been in operation since 2011 and offers a daily service in 2018. On the Yiwu-Madrid route that is now a weekly service, the first train departed in 2014, but Yiwu business leaders were exploring Landbridge options in January 2013, before President Xi’s announcement. By the time of the May 2017 Belt and Road Forum, China Railway Express, which coordinated all China Railways Corp's European services, showed connections from 27 Chinese cities to eleven European countries on its route map.

What can the BRI add to rail connections west from China across Eurasia? The BRI holds promise for extending the Eurasian Landbridge to include both the current China-Poland mainline to western Europe and a China-Istanbul mainline with spurs to the Middle East and North Africa. Indeed, Chinese maps published since President Xi's 2013 announcement highlight a route to Europe south of the Caspian Sea through Iran and Turkey.

As with the north of the Caspian Landbridge, the track for a south of the Caspian rail route already exists, including a recently opened rail tunnel under the Bosporus. China's interest in the southern route was highlighted after the easing of UN sanctions on Iran in January 2016. One week later, President Xi visited Tehran. On 28 January the first train left Yiwu for Tehran with 32 containers. It took fourteen days due to a slightly circuitous route (Figure 3). In September 2017 the first train to Tehran departed from Yinchuan, capital of Ningxia Autonomous Region, and a twice-weekly schedule for 2018 was announced. The departure point in a Muslim area of China signalled the significance of the trans-Iranian route, not just as an alternative passage to Europe, but also as a potential gateway to the Middle East and North Africa.

Why did the first China-Iran train take a circuitous route via the Kazakhstan-Turkmenistan line along the Caspian coast, which had been opened in December 2014, rather than transiting Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan on a more direct line through Meshed in northern Iran? One consideration was that Uzbekistan under long-time President Karimov had a poor reputation as a transit country, imposing substantial delays both for border checks and along the way.

In September 2016 President Karimov died. His successor, President Mirziyoyev, immediately signalled greater openness to the world, including easing border-crossing restrictions. In 2017-18 negotiations advanced between China and the Kyrgyz Republic for construction of a railway line between Kashgar and Uzbekistan, the only dotted line on Figure 1 where the track does not yet exist. The proposal is popular with China and Uzbekistan but controversial in the Kyrgyz Republic, which sees little benefit beyond limited transit fees and potential costs if the country has to take on debt to build the line. An independent report by Hurley et al. (2018) highlighted the potential for debt dependence in small countries along BRI routes, and listed the Kyrgyz Republic as one of the eight countries most at risk.1 These episodes illustrate the importance of a country's commitment to trade facilitation if it wants to be on a Landbridge route, and China's search for alternative routes, even in the face of strong opposition.

Why does the BRI involve multiple belts?

China's desire for multiple routes could come from two, not mutually exclusive, motives. Multiple routes are important because they enhance the range of transport options and reduce hold-up possibilities, which are always a danger along a single route passing through several countries. On the other hand, if the eventual intention is to cut transport times by constructing a high-speed rail line, China may be trialling the two options to determine the better security/cost trade-off.

Public investment can create alternative routes and could provide a high-speed option. Future prospects will be enhanced by investment in new or upgraded track, better rolling stock and other facilities. These are ways in which the BRI, backed by the AIIB's financial clout, could make a difference.

Investment plans such as the track connecting Kashgar to Andijan have a dual purpose for China. The connecting line will make a south of the Caspian route shorter, and also reduce the potential of Kazakhstan to demand higher transit fees. The BRI also envisages improved rail connectivity with Southeast Asia and with Pakistan. In sum, the BRI envisages a network with multiple, potentially competing (or substituting) routes.

If the intention is to cut transport times by constructing a high-speed China-Europe rail line, the cost is likely to make the two routes – north and south of the Caspian Sea – mutually exclusive as lines between China and Europe. In this scenario, China may be trialling the two options to determine the better security/cost trade-off. Although construction costs would be high, a two-day rail service between China and the EU would be a major step towards Eurasian integration and greatly improve rail's competitiveness relative to air for time-sensitive shipments.

Conclusions

The catalyst for the Landbridge rail services was car and electronics firms seeking to reduce their trade costs, evaluated in money, time and certainty, between German component suppliers and car assembly plants in China, and between Apple, HP and Acer assemblers in China and consumers of their electronics products in the EU. Since 2011 the number of trips along the Landbridge has grown rapidly, with over 3,000 in 2017. These development predated China's BRI, although the two are related and often conflated.

China's BRI is not just piggybacking on the Landbridge. The vision of the overland segment of the BRI has developed as a network of competing and complementary rail lines. The importance for China is reflected in embracement of the Landbridge plus exploration of alternative westward routes through Iran which may be reinforced by substantial investment in a shorter line from China to Uzbekistan. With a longer time-horizon, the Eurasian rail network could link Central Asia to the China-Pakistan Corridor and connect Southeast Asia to the Eurasian rail network. Commentators are right to see China's BRI as a long-term vision. That vision should not be confused with the existing Landbridge, which has been a bottom-up commercial story rather than a top-down political project.

Editors’ note: This column is based on a longer paper “The Eurasian Landbridge: The role of service providers in linking the regional value chains in East Asia and the European Union” presented at the ERIA services and GVC workshop on 2-3 March 2018 in Jakarta and circulated in the ERIA Discussion Paper Seriesas REITI Working Paper: ERIA-DP-FY2018-01. The paper draws on material in Chapter 11 of Pomfret (forthcoming).

Please click to read full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

世界華商組織聯盟《華商世界》

「一帶一路」政策去年寫入中共黨章,地位大躍升。今年一月,中國更將北極圈和拉丁美洲及加勒比海地區納入「一帶一路」倡議的範圍,讓「一帶一路」倡議成為全球化,總面積達到約為3,370萬平方公里之廣。目前,只剩美國、加拿大以及日本尚未涵蓋在這項計畫範圍內。

摩根士丹利在今年一月發布的研究報告中表示,2018至2020年期間,「一帶一路」倡議沿線國家的投資每年將成長14%。2017年中國對「一帶一路」沿線國家的投資佔中國對外投資總額的比例從2016年的8%上升至12%。未來十年,中國的投資還將促使「一帶一路」沿線國家的進出口分別成長10%和5%。受惠最多的國家有馬來西亞、菲律賓、印尼、俄羅斯、沙烏地、泰國和巴基斯坦。

一帶一路政策寫入中共黨章,地位大躍升

「一帶一路」是中國外交政策戰略的核心,去年10月中共第19次全國代表大會中,通過將「一帶一路」政策寫入中共黨章,使得「一帶一路」地位瞬間由國家政策提高到黨的核心價值。專家認為,「一帶一路」地位的提升反應了中共對於外交政策的重視程度,也顯示其對於全球領導能力的野心。

倡議涵蓋範圍再增加兩大地區——北極圈和拉丁美洲

今年1月22日,中國國家主席習近平先在力促拉美與加勒比海地區領袖,共建「跨太平洋海上絲綢之路」,接著中國在同月26日宣布「冰上絲綢之路」,並首度發表北極政策白皮書。短短5天內,中國將拉丁美洲和北極圈納入「一帶一路」倡議的範圍,讓「一帶一路」倡議成為全球化,總面積達到約為3,370萬平方公里。「一帶一路」希望新建或升級現有公路、鐵路、港口和管線網路,現在只剩美國、加拿大以及日本還沒被涵蓋在這項計畫的範圍內。

「一帶一路」全面延伸到拉丁美洲及拉勒比海地區

中國-拉美和加勒比國家共同體論壇第二屆部長級會議今年一月在智利首都聖地牙哥舉行。會議通過了《聖地亞哥宣言》、《中國與拉美和加勒比國家合作(優先領域)共同行動計劃(2019∼2021)》,並專門通過並發表《「一帶一路」特別聲明》。中拉雙方都同意共同建設一帶一路。在中國與世界各國共建一帶一路進程中,拉美應扮演重要角色。智利外長艾拉爾多·穆尼奧斯在聖地牙哥舉行的新聞發佈會上說,現在是一帶一路國際合作來到拉美的最佳時機。

習近平主席給中拉論壇第二屆部長級會議開幕致賀信指出,「歷史上,我們的先輩劈波斬浪,遠涉重洋,開闢了中拉太平洋海上絲綢之路。今天,我們要描繪共建一帶一路新藍圖,打造一條跨越太平洋的合作之路,把中國大陸和拉美兩塊富饒的土地更加緊密地聯通起來,開啟中拉關係嶄新時代。」

16世紀中國與拉美早已往來

早在16世紀中葉,「太平洋海上絲綢之路」就連接起中國與拉丁美洲。提起歷史上的「海上絲綢之路」,人們的認知為古代中國與印度洋沿岸地區經濟文化交往的海上通道。其實,在同時期歐洲「新航路開闢」的背景下,一條被稱作「馬尼拉大帆船(The Manila Galleon)」的太平洋航線,利用季風和洋流來往於菲律賓群島與美洲大陸之間,使得貿易全球化得以初步實現。這條航路中運載了大量來自中國的絲織品和瓷器,堪稱十六世紀版的「太平洋海上絲綢之路」。

當時,西班牙國力鼎盛,在完成對美洲的征服與殖民後,出於對「東方國度」的好奇以及商品的需求,1565年探險家安德烈斯.德.烏達內塔(Andrés de Urdaneta)率領一支航隊,在太平洋上開闢了這條延續長達250餘年的貿易航路。1575年,西班牙的航隊因幫助中國艦船擺脫海盜襲擾而獲得了明朝萬曆皇帝的允准,來到中國福建地區訪問。因此,隨行的傳教士馬丁·德拉達的札記是最早記錄十六世紀中國的歐洲歷史文獻之一。

這條航路承擔東西方貿易往來的重要作用。西班牙和美洲有充裕的貴金屬,中國有發達的商品經濟,在經濟互補的情況下,多邊貿易取得發展。來自中國等亞洲國家的絲綢、瓷器和手工藝品通過該航路運往美洲以及歐洲;同時,來自美洲的貴金屬、農作物、菸草等被商船帶回亞洲,最終形成了「三洲兩洋」(歐洲、亞洲、美洲;太平洋、大西洋)的多邊貿易體系的雛形。

2017拉美對中貿易出口額增長30%

中拉共建「一帶一路」有著穩固的合作基礎。2017年前11個月,中拉雙邊貿易額達2337.6億美元,同比增長18.3%。美洲開發銀行最新數據顯示,2017年拉美及加勒比地區對中國貿易出口額同比增長30%,中國對拉美出口增長貢獻最大。聯合國一份報告顯示,拉美和加勒比地區有望結束連續兩年的經濟衰退,在2017年重新實現經濟增長。

共建「一帶一路」不僅提升拉美基礎設施水平,還為當地創造就業機會,促進經濟發展,帶給當地民眾實實在在的獲得感。阿根廷重要糧食產區羅薩裏奧的糧農,可以利用中國幫助改造的鐵路,將糧食運送到布宜諾斯艾利斯港進而遠銷世界;在厄瓜多爾,用中國技術量身打造的國家公共安全控制指揮係統讓民眾安全感倍增。

中拉將加強基礎設施建設合作和互聯互通,形成橫跨太平洋,連接拉美與亞洲的大通道。中國將支持拉美建設兩洋鐵路、兩洋隧道等關鍵通道,開闢更多海上和空中航線。另外,中方將促進同地區各國貿易和投資便利化,培育中拉20億人口的大市場。「一帶一路」科技創新行動計劃也將對接拉美,雙方可在航空航天、再生能源、人工智能等新興領域合作領域,搭建中拉網上絲綢之路和數字絲綢之路。拉美地區眾多優質農產品,通過「網上絲綢之路」和「數字絲綢之路」進入中國市場。中國消費者足不出戶就能品嘗智利的車厘子、墨西哥的牛油果。

共建一帶一路構想延伸到拉美大陸,成為覆蓋各大陸、連接各大洋、規模最大的國際合作平台。

中國北極白皮書,要共建「冰上絲綢之路」

全球氣候暖化,北極海冰面積近50年以每年1%的比率退縮,最壞的推估30年後北極將呈無冰狀態,除了是生態大浩劫外,冰層下蘊藏的巨量資源、新出現的北極航道,都將成為周邊國家爭奪的焦點,目前已被形容為北冰洋「新冷戰」。制訂北極政策、規範指導北極活動是各國通常作法,中國的近鄰日本、韓國,歐洲的英國、法國、德國等國,都發布北極政策文件。隨著中國發布首份「中國北極政策白皮書」,緊張態勢愈發升高。

中國一月發布首份「中國北極政策白皮書」,以「不缺席」及「不干預」兩大綱領,表明要與各國合作借北極航道共建「冰上絲綢之路(Arctic Silk Road)」,推動北極油氣、礦產、漁業、旅遊等發展。

白皮書內容表示,在經濟全球化、區域一體化下,北極問題已超出北極國家間問題和區域問題的範疇,涉及北極域外國家的利益和國際社會的整體利益。「中國是北極事務的重要利益攸關方,是陸上最接近北極圈的國家之一。北極的自然狀況及其變化對中國的氣候系統和生態環境有直接影響,進而關係到中國在農業、林業、漁業、海洋等領域的經濟利益。」

南北兩極已納入中國發展戰略

中國近年來把參與南北兩極的管理納入發展戰略。中國國家海洋局2017年5月發表南極政策白皮書,南極洲孤懸公海,可由聯合國訂定《南極條約》規範各國和平利用;但北冰洋與周邊幾個國家接壤,北極開發比南極更具戰略價值,各大國競爭態勢也更加激烈。北極目前的權力機構是「北極理事會」,包括6個接壤國家,及另13個非北極國家為觀察員。中國申請入會遭拒3次,搬出聯合國《海洋法公約》,才在2013年獲准成為觀察員。

中共前總書記胡錦濤2012年在十八大提出「建設海洋強國」,宣示投入北極事務,繼任總書記習近平以行動落實「發展海洋強國」,把經營北極列入「一帶一路」藍圖,北極航道被喻為「冰上絲綢之路」,短短幾年,投入北極科考經費已近千億美元。

中國對外貿易貨物進出口90%依賴海運

中國涉入北極事務,關鍵在北極航道影響太重大。中國對外貿易貨物進出口,90%依賴海運,現有東、南、西3條航線,距離遙遠外,運河瓶頸,海盜出沒的危險水域,都大幅墊高航行成本;北極航道隨著冰層融解,每年夏天可航行的天數漸次增加,2017年甚至有俄羅斯油輪無破冰船引導下東航至太平洋。

北極航道開通後,對中國的意義尤其重大。上海以北的港口,穿過白令海峽進入俄羅斯的東北航道,再接北極航道,抵達目的地荷蘭鹿特丹港;走其他3條航道都要近40天,北極航道可以省1/3時間、哩程、燃料、通行費、保險費,航行成本大幅降低。

與北極圈一帶國家積極合作

中國近年在北極活動日益頻繁,除派出多艘科學考察船赴北極圈勘探外,還與俄國合作開闢北極航道,而「冰上絲綢之路」的倡議也在極力拉攏沿北極圈一帶國家。據各家媒體資料顯示,中國在2017年北方海航道破冰引航增加20%。十年來俄國北極地區中國旅客數量增加了9倍。中國在北極的政、經、旅遊等活動都有增加趨勢。

中國在北極的發展,除了在俄羅斯的亞馬爾液化天然氣專案外,北極地區最大城市阿爾漢格爾斯克市(Arkhangelsk)的深水港口改造工程,中國企業也參與其中。中俄北極開發合作已取得積極進展。兩國交通部門正在商談《中俄極地水域海事合作諒解備忘錄》,不斷完善北極開發合作的政策和法律基礎。此外,兩國企業積極開展北極地區的油氣勘探開發合作,商談北極航道沿線的交通基礎設施建設。

以俄羅斯在北極地區開展規模最大的國際能源合作項目亞馬爾液化天然氣專案為例,中國石油天然氣集團公司參與運作,截至2017年10月底,雙方已簽訂96%產量共計1478萬噸液化天然氣長期銷售協議。

建造天然氣工廠需要的142塊模組中,包括中國石油集團海洋工程等7家中國企業承攬了120個。專案建設及運輸產品所用的30艘船舶中有7艘是中國製造,15艘天然氣運輸船中的14艘由中國企業負責營運。

中國的「冰上絲綢之路」還延伸到冰島和芬蘭。2012年中冰兩國簽署《中冰海洋和極地科技合作諒解備忘錄》,目前雙方極地合作主要集中在科研領域,由中國極地研究中心和冰島研究中心聯合設立的極光觀測台將於今年投入使用,建成後將接納來自中國、冰島及其他各國的科學家,為人類認識北極及應對氣候變化作出更多貢獻。

芬蘭北極中心表示,芬蘭積極鼓勵中國參與北極事務相關合作。目前芬蘭正評估建設一條北冰洋海底光纜,建設歐亞大陸間的海底絲綢之路。預計最快2020年建成後,將成為連接歐洲和中國最快的資訊通道。

「一帶一路」建設海上合作,共建三大藍色經濟通道

中國國家發改委、國家海洋局聯合在2017年發布《「一帶一路」建設海上合作設想》,計劃與沿線國家合作建設三條藍色經濟通道。「一帶一路」建設海上合作以中國沿海經濟帶為本,連接中國-中南半島經濟走廊,經南海向西進入印度洋,銜接中巴、孟中印緬經濟走廊,共同建設中國-印度洋-非洲-地中海藍色經濟通道;經南海向南進入太平洋,共建中國-大洋洲-南太平洋藍色經濟通道;積極推動共建經北冰洋連接歐洲的藍色經濟通道。

這是首次將北極航道明確定位成「一帶一路」三大主要海上通道之一。冰上絲綢之路有可能縮短中國到歐洲的最短航線,比傳統航線縮短25%至55%。

依據美國智庫報告顯示,中國在北緯60度以北地區的投資已經接近900億美元,其中與北極有關的投資項目達21個,價值超過10億美元。

原文刊載於世界華商組織聯盟《華商世界》第三十七期2018年4月至6月號,請按此閱覽原文。

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Tham Siew Yean, Senior Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- The DFTZ was launched in November 2017 in partnership with Jack Ma, Executive Chairman of the Alibaba Group.

- It aims to connect Malaysia’s SMEs globally through Alibaba-inspired electronic world trade platforms that are being established to support greater exchange between Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) countries.

- DFTZ challenges will include:

- Budgetary incentives to increase imports via e-commerce will intensify competitive pressures on domestic producers, although it can enhance transhipment.

- E-commerce platform usage will require an SME to have an export strategy, including an understanding of the regulatory regimes and documentation needed from home and importing countries.

- It remains to be seen if SMEs will sustain their membership on these platforms once government financial assistance ends, especially if the potential benefits do not materialize as expected, or quickly enough.

INTRODUCTION

China’s e-commerce giants have been quick in linking their global expansion to the aspired Digital Silk Road of China. In particular, Alibaba founder Jack Ma’s brain child, the electronic world trade platform (e-WTP), aims to connect small businesses globally through trade. This platform is associated with the Digital Silk Road since countries along the BRI are the most important regions for Alibaba and Jack Ma’s global expansion plans.

The establishment of the Digital Free Trade Zone (DFTZ) in Malaysia in partnership with Jack Ma, as the first e-WTP established outside China, is thus a step towards developing the Digital Silk Road. Currently, the only other eWTP that exists in the world is at Alibaba’s home province of Hangzhou. The DFTZ also aims to support Malaysia’s e-commerce dream as articulated in the country’s National E-commerce Strategic Roadmap, launched in 2016. In this Roadmap, the share of e-commerce in Malaysia’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is targeted to increase to 6.4% by 2020 from 5% in 2012, by bringing in 80% of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) into the e-commerce world as well as by expanding market access through exports, investment and employment opportunities. Currently, it is reported that nine out of ten businesses in Malaysia are SMEs, of which 28% apparently have an online presence, with 15% using this involved in exports. The DFTZ specifically aims to facilitate SME export activities by providing platforms, e-fulfillment facilities and enhanced trade facilitation measures.

This article examines how the DFTZ will enhance SME export opportunities and the outstanding challenges that SMEs face in entering the export market through an ecommerce platform.

HELPING SMEs EXPORT

A traditional duty-free zone is a physical area into which goods can be imported duty free for further processing or for re-exporting. The DFTZ differs from this traditional zone in that it has a specific aim of digitizing trade to help SMEs function in international markets. The specific export target for SME is USD38 billion by 2025. If reached, this will make Malaysia Asia’s leading transhipment hub that same year. The DFTZ helps SMEs export by “connecting them to eMarketplaces, government agencies, cross border logistics providers, and cross border payment providers.”

E-commerce trade needs a whole range of services to support the speedy delivery of goods to customers. E-fulfilment, which encompasses the whole process from receiving a sales order to delivering the order swiftly to the customer, and trade facilitation, are therefore important components in this venture. The DFTZ aims to provide an eFulfilment hub, a satellite services hub and an eServices Platform. Its development is divided into two phases: the first is controlled by Pos Malaysia, which at a cost of RM60 million has been upgrading and renovating the former Low Cost Carrier Terminal (LCCT). This is already currently operational. The government budget for 2018, as announced in October 2017, includes an allocation of RM83.5 million for the development of this first phase. This mode of funding in the first phase of development differs from the traditional foreign direct investment (FDI) model, where the foreign technology partner usually provides some or all of the capital.

The satellite services hub aims to be a premier digital hub for global and local internet-related companies that are geared towards the Southeast Asian market. This includes end-to-end services as well as networking and knowledge-sharing.

In the second phase, Cainiao Network, the logistic arm of Alibaba, will partner Malaysia Airports in a green-field investment, which will be operational in 2020. Alibaba will reportedly host its regional eFulfilment hub at the Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KLIA) Aeropolis DFTZ Park. This Park will build on existing air freight infrastructure to include sea freight via Port Klang and railway cargo to Bukit Kayu Hitam, which will support a regional multimodal transhipment hub. The hub will subsequently be linked to Alibaba’s planned eWTP hubs in other countries.

Alibaba’s financial services will also be included eventually. Two of Malaysia’s financial services providers, Maybank and CIMB, have entered into an agreement with Ant Financial Services Group to establish the Alipay mobile wallet in Malaysia. Alibaba Cloud, the cloud computing arm of Alibaba group is also reportedly planning to establish a datacentre in Malaysia.

For the eServices platform, besides providing market access, integrated trade facilitation measures have reduced the cargo clearance time from six to three hours at the KLIA Air-Cargo Terminal 1 (KACT1). This is critical for the speedy delivery required in ecommerce transactions.

Currently, the two main e-commerce platforms available at the zone are Alibaba and Lazada, which has sold 83% of its equity stake to the former since 2017. According to Malaysia Digital Economy Corporation (MDEC), there will be new e-commerce platforms joining from the second quarter of 2018 onwards. However, SMEs can also list in various e-commerce platforms outside the zone, including Alibaba and Lazada. In fact, Malaysia External Trade Development Corporation (MATRADE) has had an e-Trade programme with Alibaba since 2014, whereby approved SMEs are given an e-voucher worth RM1000, which is meant to defray half of the expenses for subscribing to Alibaba e-Trade Global Supplier Package. In January 2017, the e-Trade incentive for approved SMEs has been upgraded; it is no longer confined to Alibaba alone and the amount has also increased to RM5000, with RM2,500 for listing/subscribing purposes and another RM2,500 for e-commerce expenses associated with e-marketplaces. The main advantages of the zone for SMEs are therefore the eFulfilment hub, e-services, and trade facilitation measures that are or will be made available there. SMEs are also able to experience better exchange rates and lower shipping costs, based on customer feedback from Transcargo.

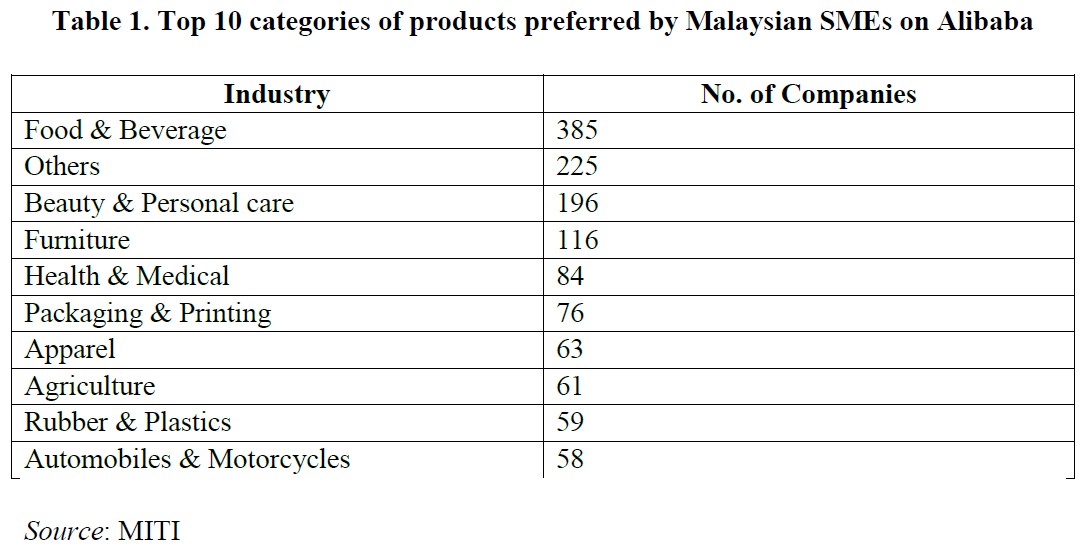

To date, about 2,072 export-ready Malaysian SMEs are on the ecommerce platforms in the DFTZ. Selangor, Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur and Melaka are the three states with the biggest number of SMEs participating in the DFTZ (69%), while the top three products preferred by Malaysian SMEs on Alibaba are food and beverage, others and beauty and personal care, which are mostly consumer products (Table 1).

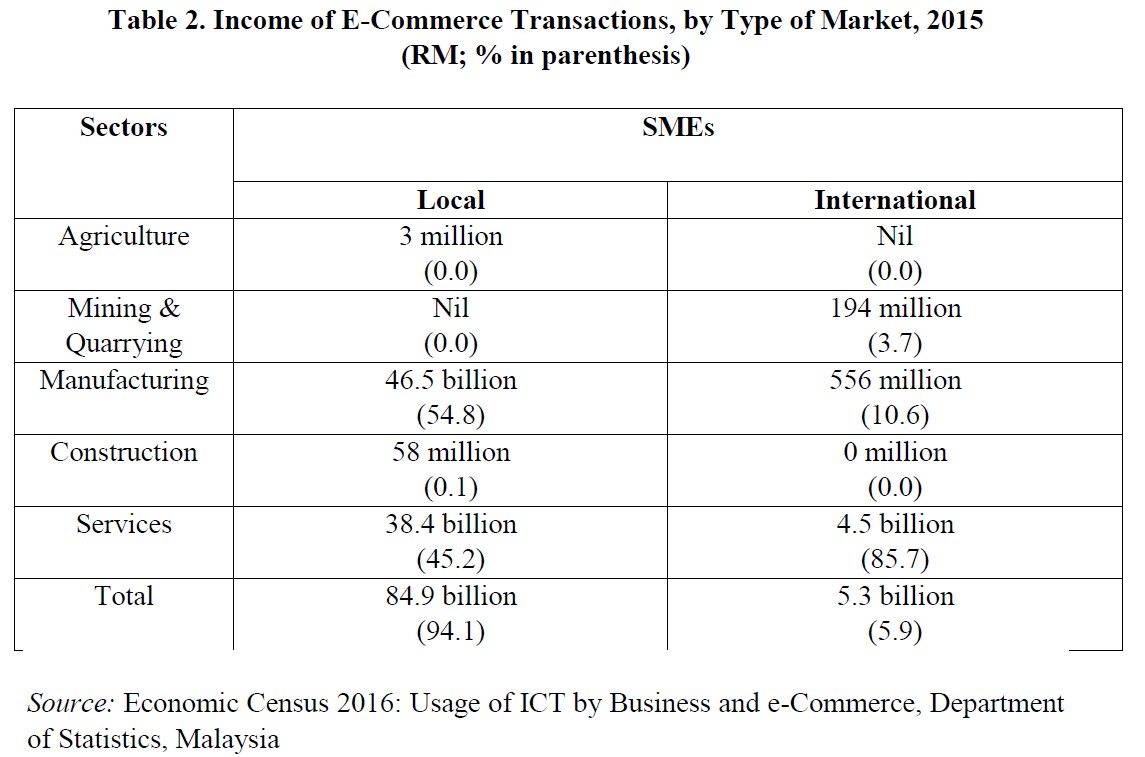

OUTSTANDING E-COMMERCE EXPORTING CHALLENGES FOR SMEs

While for SMEs to join the e-commerce platform is a big step forward, using the platform to export is a bigger challenge for them. According to Malaysia’s Economic Census 2016, 43,460 SMEs are engaged in e-commerce, but only 5.9% of their income from ecommerce are derived from international transactions, which includes imports as well (Table 2). Moreover, the services sector is the largest contributor to international income from e-commerce transactions. Therefore, not many SMEs on ecommerce platforms are able to generate export revenues, and most of them focus on the domestic market. This is why the emphasis in the MITI website is on export-ready SMEs and not necessarily exporting SMEs.

The actual number of Malaysian SMEs that were already listed on Alibaba before the establishment of the DFTZ, is not known, but it appears that these have not necessarily been using the platform for exports, but for prestige. This is especially true of the Gold members. SMEs in general lack understanding of ecommerce, and lack competent personnel to conduct ecommerce activities and market goods and services. Therefore, SMEs that are passive exporters may consider being on an ecommerce platform as an end goal. Once there, they are happy to simply wait for buyers to discover them. Active or intentional exporters tend instead to seek out information on their competitors, the pricing of rival products and who the main customers are, from the same platform as well as other platforms. They will then reposition their product, using both product and price differentiation strategies to find buyers instead of waiting for buyers to find them. But, this requires SMEs to have an ecommerce export strategy, as well as personnel dedicated to this purpose. Furthermore, those who are not able to generate new or additional export revenues from their membership on the Alibaba and Lazada platform, may discontinue the association after a while.

Second, while the zone expedites the export documents needed, it will still require SMEs to obtain all the necessary documents by themselves. More importantly, it will also require them to obtain all the mandatory documents needed from the importing country as well. These may include legitimate concerns from the importing country such as sanitary and phytosanitary standards found in the World Trade Organization (WTO)’s Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS) Agreement. This is especially important in the case of certain consumables such as food and healthcare products, where SMEs will need to comply with local regulations for manufacturing consumables such as having a Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) certified facility that meets Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) standards as well as complying with the food safety requirements of the importing country. However, these non-tariff measures (NTMs) are sometimes used as importing barriers, be it intentionally or intentionally, and are called non-tariff barriers (NTBs). The fall in tariffs due to multilateral, regional and bilateral liberalization has been accompanied by a converse rise in NTBs, globally. Yet, SMEs in Malaysia and other countries continue to be ignorant about the relevant regulations, requirements and procedures when they export to other countries. These barriers will continue to restrict SMEs in penetrating the export market, even with the full availability of the promised infrastructure in the zone. Hence, they will need to learn how to comply with rules and regulations, as is the case with offline exports.

Budget 2018 also announced that goods bought online will be exempted from tax in the DFTZ as long as they are worth RM800 (about USD 203) and below — a higher threshold than the earlier de minimis value (RM500). This encourages import, be it for personal consumption or for re-export, although goods will have to pay the Goods and Services (GST) tax if and when they leave the zone. In contrast, China’s de minimis is USD8, which discourages imports of higher value. This, together with the declining comparative advantage of Malaysia’s exports of consumer goods to China, inevitably implies that competition, especially from China, will further intensify with the establishment of the DFTZ. Although the transhipment of goods may increase, this may come at the cost of some SME producers exiting the industry, including some SME retailers and local SME third party ecommerce providers, as they will face stiff competition from the DFTZ.

CONCLUSION

The establishment of the DFTZ is hailed as a milestone in Malaysia’s national digital economy agenda. It is currently tapping on Alibaba’s system and technology for facilitating ecommerce development in the country. The cost of all these developments is currently funded by the Federal government’s budget allocation and Pos Malaysia.

The wish to increase the export contribution of SMEs from the current 18.6% to 23% by 2020, makes it necessarily for the government to use ecommerce for that purpose. Yet getting on board the ecommerce train does not necessarily increase exports. Changes in the SMEs’ ways of doing business will be needed. SMEs will need to embrace exporting activities with a proper e-commerce export strategy, including compliance with the rules and regulatory requirements of targeted export markets. In particular, the DFTZ also eases entry of imports as the change in the de minimis threshold favours imports over exports. This increases competitive threats to local SMEs, which are already facing declining comparative advantages vis-a-vis China, especially in consumer goods.

The establishment of the DFTZ will therefore require SMEs to formulate new business strategies that will help them survive in the domestic market and penetrate the export market.

This commentary first appeared in ISEAS Perspectives 2018 no 17. Read the original article here.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Jonathan E. Hillman, Fellow, Simon Chair in Political Economy, and Director, Reconnecting Asia Project

The issue:

- Unable to repay its debt, Sri Lanka gave China a controlling equity stake and a 99-year lease for Hambantota port, which it handed over in December 2017.

- The economic rationale for Hambantota is weak, given existing capacity and expansion plans at Colombo port, fueling concerns that it could become a Chinese naval facility.

Recommendations

- Recipient countries should link infrastructure projects to broader development strategies that assess projects within larger networks and monitor overall debt levels.

- The international community should expand alternatives to Chinese infrastructure financing but cannot and should not support all proposed projects.

The view from Hambantota’s Martello Tower says it all. Built by the British in the early 1800s as a lookout post, the small circular fort occupies a hill on Sri Lanka’s southern coast. Look west, along that coastline, and shipping cranes rise above a new port. Look south, out to the Indian Ocean, and hulking ships move cargo along one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes. These images could converge in the coming years, but on most days, they remain miles apart. Last year, only 175 cargo ships arrived at Hambantota’s port.

This gap explains how Hambantota became a cautionary tale in Asia’s infrastructure contest. The port was intended to transform a small fishing town into a major shipping hub. In pursuit of that dream, Sri Lanka relied on Chinese financing. But Sri Lanka could not repay those loans, and in 2017, it agreed to give China a controlling equity stake in the port and a 99-year lease for operating it. On the day of the handover, China’s official news agency tweeted triumphantly, “Another milestone along path of #BeltandRoad.”

The challenge, of course, is that political incentives are skewed toward starting big projects sooner without mitigating risks.

Not everyone is celebrating. Negotiations around the port sparked local protests and accusations that Sri Lanka was selling its sovereignty. Some observers worry that China’s infrastructure investments are creating economic dependencies, which are then exploited for strategic purposes. In 2014, a Chinese submarine docked at Colombo, Sri Lanka’s capital, setting off alarms about China’s expanding military footprint. Unlike Colombo, where Sri Lanka’s navy is headquartered, Hambantota is more isolated and could offer Chinese vessels greater independence.

Sri Lankan officials have tried to calm those fears. “Sri Lanka headed by President Maithripala Sirisena does not enter into military alliances with any country or make our bases available to foreign countries,” Sri Lankan Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe said in August 2017. In February 2018, Sri Lanka’s highest-ranking military officer said, “There had been this widespread claim about the port being earmarked to be used as a military base. . . . No action, whatsoever will be taken in our harbor or in our waters that jeopardizes India’s security concerns.” Sri Lanka’s parliament approved the agreement, but the text has not been made public, allowing suspicions to fester.

Political Ambitions, Economic Realities

As speculation continues about Hambantota’s future, its past provides lessons for Asia’s broader infrastructure competition. For recipient countries, the case underscores the importance of assessing infrastructure projects as part of an overall development strategy. Infrastructure projects often look more attractive in isolation, but their long-term success hinges on being part of a wider network, whether transportation, energy, information, or other systems. A broader approach also draws attention to debt sustainability. The challenge, of course, is that political incentives are skewed toward starting big projects sooner without mitigating risks.

Hambantota’s port did not appear overnight, but resulted from a series of Sri Lankan government decisions. Many Chinese-funded projects in Sri Lanka have been unsolicited, but Hambantota’s port is not one of them. Constructing a port at Hambantota has been part of Sri Lanka’s official development plans since at least 2002. In 2003, SNC Lavalin, a French engineering firm, completed a feasibility study for the port. A Sri Lankan government-appointed task force reviewed and ultimately rejected the study, faulting it for ignoring the port’s potential impact on Colombo Port, which in recent years has handled roughly 95 percent of Sri Lanka’s international trade.

Hambantota’s main challenge came from within Sri Lanka itself.

In 2006, Ramboll, a Danish consulting firm, completed a second feasibility study. It took a relatively optimistic view of the port’s potential, basing traffic projections on Sri Lanka’s future growth and overflow from existing ports at Colombo, Galle, and Trincomalee. Dry and break bulk cargo (commodities and goods loaded individually rather than in standard containers) would provide the main source of traffic until 2030, when the balance would start shifting toward container traffic. By 2040, the port would handle nearly 20 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU), roughly as much as the world’s fifth busiest port in 2015.

With that assessment in hand, Sri Lankan President Mahina Rajapaksa was even more eager to pursue the project. Elected in 2005, Rajapaksa had promised to develop Sri Lanka’s southern districts, especially his home district of Hambantota, which was among the areas devastated by the 2004 tsunami. During Rajapaksa’s tenure in office, Sri Lanka embarked on a series of ambitious projects. Many of these big-ticket projects—including an international airport, a cricket stadium, and the port—had three things in common: they used Chinese financing, Chinese contractors, and Rajapaksa’s name.

Chinese loans were often at high rates. The first phase of the Hambantota port project was a $307 million loan at 6.3 percent interest. Multilateral development banks typically offer loans at rates closer to 2 or 3 percent, and sometimes even closer to zero. One reason China is successful in locking in these higher rates is that better alternatives are often unavailable. Another reason is that Chinese loans, while often requiring the partner to use Chinese contracts, are not as stringent in their requirements for safeguards and reforms. There were no competing offers for Hambantota’s port, suggesting that other potential lenders did not see rewards commensurate with the project’s risks.

Putting political ambitions ahead of market demands, this approach failed to consider Hambantota port within a larger development strategy. Critically, the port at Colombo handled 5.7 million TEU in 2016, has not reached capacity, and will expand in the coming years. If Colombo port’s most ambitious plans are realized, its capacity could expand to 35 million TEU by 2040. Early plans for Hambantota focused on offering fuel services, but under Rajapaksa, it was scaled up to include other activities, many of them already carried out at Colombo. In sum, Hambantota’s main challenge came from within Sri Lanka itself.

The political environment changed in 2015, when Maithripala Sirisena unseated Rajapaksa, but the new government’s options were limited. It reexamined some deals and halted construction at Hambantota’s port. While well-intentioned, this also delayed any revenue the port could generate, effectively making it even more difficult to service the loans. By 2015, some 95 percent of Sri Lanka’s government revenue was going toward servicing its debt, and the government initiated debt renegotiations with China. Talks culminated in the 70 percent equity and 99-year lease deal.

The Path Forward

Highlighting the mistakes that led to Hambantota’s handover is easier than identifying a path forward. But Sri Lanka and its partners are not without options for limiting the damage and preventing similar outcomes in the future.

For its part, the Sri Lankan government could release the full text of the port agreement to help address concerns about the port’s future use. It could also improve government procurement and accounting processes. National debt remains a major concern. In February 2018, Sri Lanka’s auditor general admitted that he could not say with certainty how much public debt the country owed. Greater transparency would help across the board, from evaluating project proposals to contracting and payments.

Advancing a “free and open” Indo-Pacific will not come free.

The challenge for Sri Lanka’s partners is to avoid throwing good money after bad. India, for example, has expressed interest in taking over the international airport near Hambantota port. Officials have suggested it could be used as a flight school. The prospect of turning a failing project around is difficult to resist. But if that attempt is unsuccessful, India risks assuming the reputational damage that China would otherwise suffer. Likewise, Indian and Japanese interest in port facilities in Trincomalee, on Sri Lanka’s east coast, should be tempered by Sri Lanka’s debt levels and the existence of competing ports in the region.

India has another type of leverage, but may not be willing to use it. Its domestic shipping laws do not allow foreign vessels to carry domestic cargo between Indian ports. If those laws were loosened, allowing for greater international participation, India’s own ports would become more active and the need for transshipment services at Sri Lanka’s ports would decline. That would likely cut into a primary source of Hambantota’s future traffic, but also negatively impact Colombo port. Perhaps the biggest barrier to implementation are the interests within India that benefit from these laws and the status quo. But at some point, a stronger response to murky Chinese port investments could include greater openness of India’s own ports.

Clearly, advancing a “free and open” Indo-Pacific will not come free. As Sri Lanka’s experience illustrates, it is not enough to warn against embarking on risky projects. When leaders weigh the short-term incentives of starting projects against the long-term risks of debt and subpar performance, the former often wins out. Better financing alternatives could limit recipient countries’ exposure to high interest rates and project terms that create dangerous dependencies. Capacity-building measures could help train governments to evaluate projects and negotiate terms.

But none of this will solve the fundamental challenge of walking away from unviable projects. Better financing alternatives cannot and should not be made available for all proposed projects. Some projects simply should not be pursued. That responsibility falls to government officials, and in democracies, the citizens who elect them. Sri Lanka’s recent local elections suggest its political winds could change yet again, potentially bringing former President Rajapaksa back to power in 2020. When you climb down from Hambantota’s Martello Tower, there is a plaque and picture of him, smiling, at the bottom of the ladder.

Please click to read full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

中國社會科學院世界經濟與政治研究所徐奇淵

[摘要]

本文估算了一帶一路沿線國家交通基礎設施的融資需求,具體包括總體融資需求及其在六大走廊的空間分佈。這一估算為一帶一路建設的融資機制研究提供了宏觀背景。本文的估算方法,以兩組相關關係的研究為基礎,即:基礎設施投資和基礎設施發展水平間的相關關係(相關關係I),基礎設施發展水平和經濟發展水平間的相關關係(相關關係II)。然後基於歷史,對未來各國經濟發展水平做出基準情形假設,在此基礎上,根據相關關係II,對基礎設施發展水平進行估算。最後,再根據相關關係I,對基礎設施融資需求進行估算。

"一帶一路"沿線區域經濟發展水平各異,基礎設施項目融資需求巨大。在此過程中,關於一帶一路基礎設施融資的諸多問題亟待回答。例如,一帶一路沿線的基礎設施的融資缺口有多大?這種融資缺口呈現何種空間分佈、項目分佈?應該使用何種機制來滿足這些融資缺口?這些融資缺口背後,其信用風險狀況如何?應該使用何種機制來防範、化解這些信用風險,使得一帶一路融資機制更具有可持續性?在回答所有這些問題之前,我們都需要知道,一帶一路沿線融資需求的基本狀況,例如總體融資需求是多少,各國的融資需求是多少,融資需求在六大走廊的空間分佈如何?只有先回答這些問題,然後結合各國的風險狀況、金融市場發展特點,才有可能準確回答前述問題。在回答前述問題基礎上,我們才有可能實現以"一帶一路"戰略為重點,科學引導資本輸出的區域和行業流向,高對外投資的宏觀效益。本文將聚焦於分析一帶一路沿線國家對交通基礎設施的融資需求,並對其進行估算。

基礎設施互聯互通是"一帶一路"建設的優先領域,是要加強公路、鐵路以及港口等交通基礎設施建設,共同維護輸油、輸氣管道等運輸通道安全,推進跨境電力與輸電通道建設,積極開展區域電網升級改造合作。與此同時,一帶一路基礎設施融資需求和融資缺口巨大但乘數效應明顯。其中,交通基礎設施的建設具有突出的重要性。關於全球範圍的交通基礎設施融資需求,很多研究機構都對未來15年,即2015年至2030年間的融資需求進行過測算。不過,對一帶一路沿線國家基礎設施融資需求的研究還較少,即便是較受關注的全球基礎設施融資需求測算,各個機構的計算結果也差異極大,從麥肯錫全球研究院Dobbs et al.的7萬億美元,到美國布魯金斯Qureshi的 27.2-31.4萬億美元,差異達到4倍左右。經合組織研究報告,聯合國可持續發展解決網絡研究報告,世界銀行研究報告的結果則更接近較小值的情形。雖然各機構的結果差異極大,不過即使按照測算的下限來看,全球基礎設施項目融資的需求也非常巨大….

估算結果

一帶一路沿線國家在交通基建方面的總體融資需求。在我們測算的基準(benchmark)情形中:2016年至2030年期間,一帶一路國家的交通基建融資需求將達到2.9萬億美元。這裡和下文所使用的美元,均為2015年美元不變價。基於基準假設的向上、向下調整,該融資需求規模也會有相應調整。

一帶一路國家交通基建融資需求的空間分佈,以中國-中亞-西亞、新亞歐大陸橋兩大走廊為主。從空間角度來看測算結果,我們可以觀察"一帶一路"建設的六大國際經濟合作走廊,其交通基礎設施建設的融資需求分別為:中巴走廊250億美元,中蒙俄走廊990億美元,中國-中南半島1640億美元,孟中印緬經濟走廊1950億美元,新亞歐大陸橋7470億美元,中國-中亞-西亞走廊7920億美元。

請按此閱覽原文。

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By ECFR

- Mathieu Duchâtel, Deputy Director of the Asia and China Programme, European Council on Foreign Relations

- Alexandre Sheldon Duplaix, Researcher-Lecturer, French Defense Historical Service

Summary

- China’s Maritime Silk Road is about power and international influence, but Europeans should not overlook the importance for China of further developing its blue economy, which already represents 10 percent of China’s GDP.

- The Maritime Silk Road already affects Europe in five main areas: maritime trade, shipbuilding, emerging growth niches in the blue economy, the global presence of the Chinese navy, and the competition for international influence.

- On balance, the Maritime Silk Road creates more competition in Europe-China relations, but it also creates space for cooperation in the blue economy and for specific maritime security missions.

- Europe should emulate China’s blue economy as an engine of growth and wealth, and encourage innovation to respond to well-funded Chinese industrial and R&D policies.

- Europeans should strengthen their contribution to maintaining a strategic balance in the Indo-Pacific region and uphold their vision of a rules-based maritime order.

Introduction

"If you want to be rich, build a road first" (要想富,先修路). There is rarely a conversation about Xi Jinping's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – his plan for greater connectivity for China across both land and sea – in which this six-character proverb does not crop up. But in the shape of the Maritime Silk Road part of the strategy, the route exists already and is vital to China's ever-growing wealth. The sea lanes of communication from China to Europe through the Malacca-Suez route are among the busiest in the world. Twenty-five percent of world trade passes through the Malacca Strait alone. China-Europe maritime trade is three times larger than trade by air freight and Eurasian railways, while the last alternative – the Northern Route through the Arctic Ocean, that China dubs the "Ice Silk Road" – is only just starting to develop….

1. Europe and the Maritime Silk Road: engaging on Chinese terms….

2. Five key implications for Europe

2.1 Maritime Trade: China’s increasing global footprint….

2.2 The risk of slow death for the European shipbuilding industry….

2.3 Towards Chinese leadership in emerging strategic industries….

2.4 The new normal in Chinese naval presence worldwide….

2.5 Responding the intensified strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific….

3. Conclusion and policy recommendations

China’s policies on facilitating the growth of its blue economy and its construction of a powerful navy are transforming the global maritime environment in which Europeans operate. Both sides seek prosperity and security, and this can create opportunities. But overall the Maritime Silk Road presents Europe with serious challenges, and it will heighten the competition element in Europe-China relations. Europe should not turn its back on the opportunities that exist but it should not turn a blind eye to the challenges either.

- The EU should put in place an EU-wide investment-screening system, and soon.

Chinese investment in European ports can be unproblematic – until a critical size is reached. This point is reached when the scale of one project in a single country leads to excessive political influence, although this can also come about through the gradual establishment of a position of dominance which threatens fair competition. In third countries, the growth of Chinese influence through port infrastructure leaves no space for a ‘win-win’ game between Europe and China. In an ideal scenario, a greater Chinese economic presence in unstable states could lead to EU-China crisis management cooperation. But the absence of any significant achievements in this area so far indicates that such an outcome is unlikely. As a result, the EU and its member states should draw a clear line for themselves between investment that helps meet European long-term interests and investment that negatively affects Europe’s competitiveness. Besides introducing an EU-wide screening policy, equally important is the need for reflection within the EU institutions and among member states about how investment-screening should apply to the maritime domain and the blue economy. For internal use, the EU could produce a “white list” of areas where cooperation with China can operate on a basis of reciprocity. The EU should make clear to China that reciprocity should be the basis for investment exchanges in the blue economy. Experts understand that reciprocity is about fairness and non-discrimination, but there is a risk of misinterpretation on the Chinese side. Europeans should seek to mitigate this through clear explanations.

- Europe should look and learn from China’s blue economy as an engine of growth and wealth.

Europe should emulate China’s strong and well-funded policies on developing shipbuilding, deep sea exploration, offshore oil and gas exploration and exploitation, shipping, and on the availability of Chinese corporations and policy banks in supporting infrastructure projects worldwide. The EU and EU member states should encourage innovation in order to preserve a European niche of expertise in key sectors of the blue economy. That said, Europeans should keep in mind that a key Chinese weakness is the risk of public resources being wasted because of non-performing loans.

- EU member states with naval forces should respond to the trend of an increasingly proactive China by setting a perimeter for engagement in the maritime domain.

China is a potential partner for three types of naval operation. Two have already formed part of Sino-European cooperation: civilian evacuations and humanitarian escorts. The third – mine countermeasures – would likely come about as a response to terrorism or a war in the Persian Gulf that neither China nor Europe want. Djibouti offers an opportunity to engage with China in the near term, given the presence of several European militaries and of an EU task force in the Gulf of Aden. As a minimum, France, the UK, Germany, Italy, and Spain should exchange liaison officers with the PLAN command in the new base through their own military presence in Djibouti. As a trust-building exercise, they should offer an upgrade in military engagement with China through Djibouti on the PLA’s three priorities (peacekeeping, escorts, and humanitarian assistance), starting with the exchange of threat assessments. The annual limited-scale joint exercise conducted by the PLAN task force and the EU’s Operation Atalanta could also be upgraded to practise in the areas of evacuations and mine countermeasures.

- Europe’s naval presence in the Indo-Pacific should focus on the defence of international law principles and on the promotion of peace in conflict resolution.

In addition to the limited engagement with the PLAN described above, European countries should also step up their naval diplomacy and exercises with other regional actors. Europe already exerts influence through the sale of naval equipment to Australia, Singapore, India, South Korea, and Malaysia, although economic interests are arguably a more important driver for these exports than strategic considerations. Europeans should view their presence and defence cooperation as a contribution to preserving peace in the Indo-Pacific region through achieving strategic balance.

This analysis of the Maritime Silk Road reveals that Europe will increasingly need to consider its approach to China as a matter of grand strategy, and not as a collection of specific policy responses around competition and cooperation with Beijing. Nothing has yet forced Europe to pick a side between China and a US-led counterbalancing coalition in the Indo-Pacific region. But the time will come when it will have to decide, and this may not be a time of Europe’s own choosing. With Xi Jinping in power for the foreseeable future, pursuing a national strategy transparently aiming for global leadership, the international environment is evolving inexorably towards more bipolarity. In this context, what happens on, by, and beneath, the world’s seas will be crucial in the international race for power and influence.

Please click to read full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By Matthew P. Funaiole, Fellow, China Power Project

Jonathan E. Hillman, Fellow, Simon Chair in Political Economy, and Director, Reconnecting Asia Project

The issue:

- China’s Maritime Silk Road Initiative (MSRI) seeks to connect Beijing with trading hubs around the world.

- Beijing insists the MSRI is economically motivated , but some observers argue that China is primarily advancing its strategic objectives.

- This article examines several economic criteria that should be used when analyzing port projects associated with the MSRI.

China’s leaders have mapped out an ambitious plan, the Maritime Silk Road Initiative (MSRI), to establish three “blue economic passages” that will connect Beijing with economic hubs around the world. It is the maritime dimension of President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which could include $1–4 trillion in new roads, railways, ports, and other infrastructure. Within this broad and ever-expanding construct, Chinese investments have been especially active in the Indo-Pacific region, raising questions about whether it is China’s economic or strategic interests that are driving major port investments.

The Indo-Pacific is already central to global commerce and will become even more important in the coming years. Each of the 10 busiest container ports in the world are situated along the shores of either the Pacific or Indian Ocean, and more than half of the world’s maritime trade in petroleum transits the Indian Ocean alone. The ocean’s commercial shipping volume has increased four-fold since 1970, with an estimated 9.84 billion tons of products being transported each year. Exports from Asian economies are expected to rise from 17 percent in 2010 to 28 percent in 2030, further indicating the economic vibrancy of the region.

Continuing this growth will require further reforms and investment. South Asia is the least integrated region in the world, with intraregional trade amounting for less than 5 percent of the region’s total trade. Standing in the way of further integration are “soft” infrastructure challenges, such as customs and trade barriers, as well as hard infrastructure challenges. The World Bank has estimated that between $1.7 trillion and $2.5 trillion needs to be invested in South Asia to close its infrastructure gap. As a result of these challenges, it is more than twice as expensive to export or import a container in South Asia than it is in East Asia.

Many of the same attributes that make a port commercially competitive can also increase its strategic utility. . . . deep water ports can accommodate larger commercial vessels as well as larger military ships.

Beijing insists the MSRI is intended to increase global integration and boost growth, but some analysts question China’s motivations, particularly those behind its investments in ports. During the first half of 2017 alone, Chinese companies announced plans to buy or invest in nine overseas ports, five of which are in the Indian Ocean. Those critical of the MSRI typically argue that while some economic factors may be at play, these investments are driven primarily by strategic objectives. At the heart of this critique is a concern that China will use ports associated with the MSRI to service military assets deployed to the region in support of China’s growing security interests. These concerns have focused on several port projects, including those in Gwadar, Pakistan; Hambantota, Sri Lanka; and Kyaukpyu, Myanmar.

One way to begin testing these competing narratives is to explore the economic viability of new port construction projects associated with the MSRI. To be sure, many of the same attributes that make a port commercially competitive can also increase its strategic utility. For example, deep water ports can accommodate larger commercial vessels as well as larger military ships. It is also true that ports with weak economic fundamentals are not necessarily strategic plays. Political incentives can also motivate the funding of questionable infrastructure projects. With few exceptions, however, these projects have been advertised by Beijing and recipient countries as economic opportunities. Examining the economic merits is a practical first step in assessing the motivations of the MSRI.

This article outlines three economic criteria that should be used when analyzing port projects associated with the MSRI: (1) proximity to major shipping lanes; (2) proximity to existing ports; and (3) hinterland connectivity. While far from exhaustive, these initial criteria are intended to lay the groundwork for more detailed assessments of individual port projects. The following sections explore these factors with reference to the three port projects (Gwadar, Hambantota, and Kyaukpyu) mentioned above.

Proximity to Shipping Lanes

One of the most important—and perhaps the most obvious—determinants of a port’s economic viability is its geographic location. Major ports are typically situated near busy shipping routes and benefit from topographical features such as deep channels or natural harbors. Sri Lanka, for instance, is strategically situated along the Europe-Asia trade route, which has contributed to Colombo Port’s status as the 25th busiest container port in the world.

More than half of the 7.6 million barrels of crude oil that China imports each day come from countries along the Persian Gulf.

In Sri Lanka’s Southern Province, a port at Hambantota is only 10–15 kilometers from the Europe-Asia trade route. Advocates for the port, which Chinese firms now operate, point out that it is even closer to those ship lanes than Colombo Port, which sits on Sri Lanka’s western coast. Given the volume of trade that travels along this maritime corridor—estimated to be 23.1 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) in 2017 and expected to grow in the coming years—they argue that Hambantota can succeed by capturing just a fraction of this traffic.

Gwadar’s proximity to shipping routes is less optimal than it appears at first glance. It is located at the mouth of the Gulf of Oman, a vital maritime passageway for tankers carrying petroleum from the Arabian Peninsula to the energy-hungry countries of East Asia. More than half of the 7.6 million barrels of crude oil that China imports each day come from countries along the Persian Gulf. However, Gwadar is too close to ports of departure to serve as an effective waypoint for ships traveling from the Persian Gulf to China. Beijing and Islamabad’s longer-term vision for Gwadar includes high-speed rail and road networks that could carry oil from ships arriving at Gwadar to Western China. This would reduce the total distance that oil would travel from the Persian Gulf to China, but increase transportation costs while incurring other risks, namely those associated with traveling through restive western Pakistan. At present, much of this supporting infrastructure is yet to be developed, as the final section of this article explains.

Proximity to Existing Port(s)

Given that most maritime traffic follows well-established routes designed to reduce shipping times, and thus costs, it comes as little surprise that some of the construction projects associated with the MSRI lie close to existing ports.

In general terms, the construction of a new port close to an established port makes economic sense if the established port cannot satisfy demand. In practice, assessing these factors is more challenging. Colombo Port, for instance, operates predominately as a transshipment port that services the Indian subcontinent, and has witnessed its throughput—measured in millions of TEU of containerized cargo—increase from 4.9 million TEUs in 2014 to 6.2 million TEUs in 2017. But with a reported capacity of 7.1 million TEUs and plans to further expand its capacity, Colombo is well-positioned to handle future growth in maritime trade.

If Colombo continues to expand its capacity to meet demands, Hambantota may struggle to attract shipping traffic well into the future. According to Sri Lanka’s Ministry of Shipping and Ports, only 183 ships arrived at Hambantota in 2017, down from 281 ships in 2016 —far less than the nearly 4,500 that annually visit Colombo. Most of the ships (40 percent) that did visit Hambantota over this period were vehicle container vessels, a result of the Sri Lanka Port Authority’s decision in 2012 to route vehicle carriers to Hambantota.

The case for Kyaukpyu is comparatively stronger. Some 200 nautical miles north of Kyaukpyu on the coastline of the Bay of Bengal is the much-maligned Port of Chittagong. For years, reports have indicated that Chittagong is congested and inefficient, with throughput in 2017 double that of the port’s designed capacity. Kyaukpyu could serve to alleviate this pressure, especially for vessels traveling between the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea. In 2017, over two-thirds of the port calls made at Chittagong by container ships and bulk carriers were conducted by vessels traveling (in either direction) between Colombo and ports along the Malacca/Singapore Straits.

Hinterland Connectivity

The commercial success of all three port projects hinges on improving their connectivity to the “hinterland” (areas located further inland). The specific requirements of this connectivity depend on the services that each port aims to provide. For example, connectivity requirements are lower for ports specializing in transshipment, which involves moving cargo between ships rather than transporting it along overland routes. Nonetheless, all three ports aspire to be more than just transshipment hubs.

At Gwadar, port facilities have advanced faster than the area’s supporting infrastructure. The port recently received its first container ship, but the lack of adequate transport connections—particularly roads and rail—between Gwadar and the more developed areas of Pakistan hamper the port’s operations. An uptick in shipping traffic at Gwadar, particularly cargo destined for locations elsewhere in Pakistan, would result in serious delays due to the area’s limited connectivity. Importantly, connectivity isn’t just limited to transportation. Ample water and power supplies are also critical. Reports also indicate a shortage of basic services at Gwadar, including potable water.

The commercial success of all three port projects hinges on improving their connectivity to the “hinterland.”

Much like Gwadar, Hambantota’s port is relatively isolated from Sri Lanka’s more developed areas. According to one optimistic projection , traffic leaving the port could surge from under 1,000 vehicles a year to nearly 25,000 vehicles by 2040. Much of that traffic would be destined for areas closer to Colombo. To service this growth, Sri Lanka’s road and rail networks would need to be considerably upgraded and expanded. Some of these supporting projects are underway.

The success of Kyaukpyu could also depend on the development of the China-Myanmar Economic corridor. The proposed multiphase project is designed to promote interstate connectivity between areas in southwest China and Myanmar. These connections, including oil and gas pipelines, could also help to expedite trade from Europe and the Middle East to inland China by allowing it to enter the continent at Kyaukpyu rather than at Chinese ports in the South China Sea, where goods must travel overland for hundreds of miles before reaching inland provinces like Yunnan.

To be sure, connectivity gaps are not limited to Chinese port investments. Chabahar Port in Iran faces similar challenges, particularly its isolation from Iran’s railway network. State-backed companies in India have recently announced investments aimed at addressing this shortcoming.

Sometimes better investments do not offer as many political benefits.

Political Currents and Changing Tides

These cases highlight how the domestic political incentives for port construction do not always align with the economic merits. Hambantota, Gwadar, and Kyaukpyu are all advertised as engines of development for historically underdeveloped areas. As rural locations, they are less connected to broader transportation networks. In other words, the appeal of building a “game-changing” port in an undeveloped area almost always brings with it broader connectivity challenges, most of which are not captured in the cost of the port itself.

Sometimes better investments do not offer as many political benefits. Improving an existing port’s operations is often a cost-effective way to increase trade competitiveness, but technical and management enhancements do not generate the same excitement as ribbon-cutting and ground-breaking ceremonies. The duration of many infrastructure projects also magnifies the political incentives for starting projects. Successful projects can take years to complete and even longer before they become profitable. As such, officials who reap the political benefits of the new projects are often unaccountable for the project’s long-term performance.

Maritime trade is a fluid business. Shipping lanes are slow to change, but they are not immune to revision. As the Arctic warms, for example, northern sea lanes are remaining open for longer each year. There are also ambitious plans, like the Kra Canal, that could impact future shipping lanes, albeit not as dramatically as the Suez and Panama Canals did in the past. Individual ports may rise and fall, based not only on their location but also on their ability to compete and provide services. As the new ports examined in this article mature, they will need to overcome connectivity and services challenges or they will remain constrained. Further research is needed, not only to better understand each port’s characteristics, but also their related connectivity projects.

Please click to read full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Five years on from the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative, the second part of a report on the implications for Turkey of China's economic masterplan focuses on the likely long-term geopolitical transformation of the wider Eurasian region.

China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) presents a number of opportunities for Turkey, many of which will have wide-ranging implications for the country's economy and geopolitical standing. Naturally enough, many within its business, academic and governmental sectors have strong views as to its possible benefits and likely pitfalls.

With a particular emphasis on the broader geopolitical issues that may influence Turkey's view of China's mega-project, a number of senior Turkish figures were asked to give their assessment of the current state of play. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the unprecedented scale and nature of the BRI, it was clear, overall, that no real consensus has yet emerged.

Stabilising Influence

While the BRI's primary effect will be economic, the shift in trading routes and patterns it is set to cause will, inevitably, lead to changes in political relationships across Eurasia. While it is a long-held maxim that improved trade and improved stability go hand-in-hand, not everyone in Turkey seems wholly convinced.

There is, however, a widely shared belief that the BRI will transform far more than just trade arrangements. One Turkish businessman who is convinced of that is Şahin Saylik, General Manager of Kırpart, a leading automotive-parts company with operations in China. Seeing its implications as potentially very broad indeed, he said: "The BRI will definitely have a major geopolitical effect in terms of bringing peace to unstable regions, for instance.

"Good trading partnerships will force countries to have more understanding of, and be more sympathetic with, the region's political relationships. Stabilisation and security are must-haves if the project is to succeed.

"It is a gigantic undertaking that involves considerable economic, cultural, social and political development, as well as stabilisation and peace in the region. As a geographically important player, Turkey can only benefit from the positives the project offers."

Turgut Kerem Tuncel, a senior analyst at Ankara's Center for Eurasian Studies, is another who believes the BRI will be a stabilising influence throughout the Eurasian region, saying: "Potentially, the BRI will have a great geopolitical effect on the region. Liberal internationalist experts view the BRI as a driver for peace, arguing that enhanced trade ties among countries will inevitably aid stability. Certainly, there is some truth to that view."

Iran's Importance

One Eurasian nation that could particularly benefit from an increase in regional trade and stability is Iran. It is currently facing a renewal of US sanctions after the Trump administration pulled out of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) nuclear agreement between Tehran and the US, UK, France, Germany, China and Russia. Coupled with the recent anti-Iranian rhetoric from Israel and the US, the move may mean the BRI takes on an even greater significance within its borders.

Highlighting the importance of Iran to Turkey, Salih Işik Bora, an International Trade Analyst at the Center for Eurasian Studies, said: "Turkey has many good reasons to proactively address the geopolitical challenges that could negatively impact on the BRI. Perhaps the most important is the advancement of collaboration with Iran, as the two countries will together form a critical juncture between Central Asia and Europe.

"Tehran is currently moving towards wider integration with the world economy. A major indicator of this trend is Iran's improving ties with Europe, as illustrated by French oil company Total's recent signing of a $4 billion treaty with Tehran. At the same time, Beijing is clearly interested in enrolling Iran in the BRI, as was shown by Xi Jinping's 2016 announcement that China wants to increase its bilateral trade with the country to $600 billon over the next 10 years."

Pointing out that even the end of the JCPOA nuclear agreement and the threat of fresh sanctions may not halt Iran's progress towards greater international economic integration, he added: "Even the American business community seems eager to lift the current sanctions. Boeing, for instance, recently signed a $3 billion deal to supply civilian aircraft to Iran."

Highlighting Afghanistan as another potential beneficiary, Selçuk Çolakoğlu, Professor of International Relations at Ankara's Turkish Center for Asia Pacific Studies, said: "In order to be successful, the BRI is reliant on a wide range of co-operative efforts across a host of different sectors, from infrastructure to developmental aid. This is hugely significant, given that the BRI projects put forward by other countries have largely concentrated just on developing their transportation infrastructure and improving their integration into the world market through trade liberalisation.

"All these efforts aim to build up regional integration through economic and political co-operation. Afghanistan, as one of the heartlands of Asia, could theoretically become a key hub for transit transportation, regional trade and economic and political co-operation with the help of BRI-related initiatives."

Increased Competition

While improved trade may enhance peace and security, a freer flow of goods and services is not without its potential downside. Addressing this particular issue, Tuncel said: "The BRI may well trigger competition among countries. Eurasian nations could compete with one another to try to ensure that various trade routes pass through their own territories as a way of elevating their own geopolitical significance and maximising their own economic benefits. Nevertheless, as long as the competition remains healthy, it may also facilitate the overall modernisation of the region.

"There may also be competition among the major powers. For example, while the EU seems to have a broadly positive view of the BRI, some indicators show the US is somewhat more cynical.

"Russia's view of the BRI is also worth considering. While the Kremlin wants to create a closed regional economic zone, with the Eurasian Economic Union evolving into a political bloc, the success of the BRI depends on openness. As China is likely to become a dominant force in the region, that may cause problems in its future relationship with Russia."

Looking East

As the EU, the world's largest single market, is on its doorstep, Turkey has long been reliant on exporting its goods to Europe. Its attempts to actually join the bloc have been fruitless and, given the current political climate, look set to remain just that.

For some, though, the BRI gives the country an opportunity to turn away from the west and seek new trading relationships in the east. Clearly an advocate of this particular strategy, Nicol Brodie, an analyst with the Australian National University in Canberra, said: "The BRI is an opportunity for Turkey's President Erdoğan and his government to reduce its economic dependence on the European economies and hedge against deteriorating relations with the United States and NATO. It provides Turkey with trade, foreign direct investment and is a vehicle through which it can establish its economic and cultural footprint across central Asia.

"Turkey's relations with the United States, its long-term security partner, and Germany, its major economic partner, have been frosty for some time. The BRI, though, provides Turkey with a way to explore alternatives to these existing economic and strategic partnerships and simultaneously helps China create its own economic architecture.

"Crucially, it allows both nations to strengthen their relationship without entering into direct opposition with the US. It would be difficult, for example, to find specific reasons to support any claim that the Sino-Turkish relationship undermines the latter's NATO membership."

Tuncel also saw distinct benefits in Turkey potentially pivoting from the west to the east, saying: "Obviously, Turkey's deteriorating relations with the US and the EU, which dashed its hopes of accession to the EU, has generated additional interest in the BRI.

"In Turkey, a visible section of the intelligentsia and political class has voiced support for Turkey's looking east at the expense of its historical inclination attachment to the west. For them, deeper relations with China, Iran and Russia are needed to counter the west's perceived hostility.

"The BRI is a potential lever that can allow Ankara to become the ultimate kingmaker in the Eurasian arena, while increasing its economic and political sphere of influence. If Beijing and Ankara can reach a suitable accommodation, Turkey may well become the backbone of the BRI."

Problems for the West

As Turkey increases its focus on its Eurasian connections, the relevance of western institutions is likely to decrease. This may create difficulties for the US and NATO, given Turkey's key position in relation to the Middle East, the Balkans and the Black Sea states.

Focusing on this particular problem for the west, Brodie said: "This will inevitably put the United States and its NATO partners in a difficult position. While they cannot oppose a trade relationship, they will still be worried about Turkey's attempts to slowly decouple itself from the west's economic and strategic embrace.

"Overall, Turkey's engagement with the BRI and its growing relationship with China is likely to become one of the more permanent fixtures of Turkish politics. The BRI, after all, is compatible with Turkey's defence and economic integration with NATO and Europe."

Complacency Concerns

While many in Turkey are optimistic about the opportunities the BRI presents, there is a growing feeling that this very confidence may present risks, with Turks assuming that the country's advantageous geographic position ensures its advantageous participation. Sounding a warning note in this regard, Tuncel said: "Over-confidence among the majority of Turkish experts and policy makers over the country's geostrategic position is a worry. While it is true that Turkey is in a strategically very important location, this only becomes meaningful if the relevant economic and infrastructural projects are actually implemented.

"This requires deeds rather than bombastic rhetoric. In brief, over-confidence, idleness and the possibility of falling behind with infrastructure modernisation seem to be the major obstacles that have to be overcome to ensure that Turkey can both be fully engaged with the BRI and subsequently benefit from its involvement."

George Dearsley, Special Correspondent, Ankara

For further analysis of Turkey's likely role within the BRI, see part one of this report: "While Concerns Linger, Turkey's BRI Commitment Remains Steadfast", 14 May 2018.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

中國外經貿企業服務網

習近平總書記在2013年訪問中亞四國和東盟期間,先後提出了"絲綢之路經濟帶"和"海上絲綢之路"的戰略構想,並在2013年12月召開的黨的十八屆三中全會上通過的《中共中央關於全面深化改革若干重大問題的決定》關於"構建開放型經濟新體制"中進一步明確提出:"加快同周邊國家和區域基礎設施互聯互通建設,推進絲綢之路經濟帶、海上絲綢之路建設,形成全方位開放新格局。""一帶一路"倡議的提出,是時代的要求,是把快速發展的中國經濟同沿線國家利益結合起來,利用中國自身發展優勢實現自身發展的同時,帶動其他國家乃至世界經濟發展的偉大創舉。

亞洲開發銀行(簡稱"亞開行")在2014年發佈的《亞洲發展展望報告》裡面指出,雖然亞洲區域的經濟增長速度有所放緩,但其仍然是全球主要國家中增速最快的區域,尤其是該區域主要經濟體正在執行的改革措施將繼續推動該區域領銜全球經濟增長,因此亞洲區域是實行"一帶一路"倡議的重點。

經濟的快速發展需要相應的配套設施,然而目前亞洲國家在基礎設施上依然存在巨大的不足。根據亞開行的預測,2010-2020年亞太地區對基礎設施的需求高達8萬億美元(見表1)。基礎設施的建設是支持經濟發展的重要保障,也是實現"一帶一路"倡議互聯互通的基本要求,而基礎設施的建設需要巨額資金的支持。

"一帶一路"倡議實施過程中的資金需求主要集中在以下幾個領域:一是通信、供水和環衛設施等基礎設施領域。沿線的中亞、東南亞等國家的基礎設施較為落後,對基礎設施的新增需求強烈。二是交通、港口等跨境通道領域。"一帶一路"的暢通需要提升鐵路、公路、管道等通道能力。三是能源、資源領域。"一帶一路"跨越的地區能源和資源豐富,特別是中亞、俄羅斯等地區蘊藏著豐富的礦產、石油、天然氣等資源,開發潛力巨大。"一帶一路"沿線國家雖然經濟發展迅速,但是差異較大,一些國家市場制度不完善,在這些國家進行基礎設施建設,存在資金需求量大,投資回報期長而且未來收益不確定的問題。與此同時,"一帶一路"沿線國家間目前跨境金融合作的層次較低,大部分的貸款集中在油氣資源開發,管道運輸等能源領域,其他領域未能從中受益。因此,為了順利推進"一帶一路"倡議的實施,為"一帶一路"沿線特別是亞洲區域的基礎設施建設提供資金支持,我們需要對融資進行總體的規劃,構建以絲路基金為引導,以亞洲基礎設施投資銀行等國際開發性金融機構為重要支撐,以國內政策性銀行、國內商業銀行以及民間投資機構為主要基礎的多元聯動的融資機制。

充分發揮絲路基金的引導作用

2014年11月,在加強互聯互通夥伴關係對話會上,習近平總書記發表了《聯通引領發展夥伴聚焦合作》的重要講話:中國將出資400億美元成立絲路基金。絲路基金成立的初衷是為"一帶一路"服務,主要使命是為"一帶一路"沿線國家提供基礎設施建設、資源開發、產業合作等有關項目提供投融資支持。絲路基金是一個開放的平台,它的包容性和多元化可以為"一帶一路"倡議實施提供豐富的融資渠道和方式,可以吸引有資金實力、有知識和管理經驗的銀行和投資機構參與,多方彙聚就可以優勢互補,博採眾長。絲路基金的定位是中長期的開發投資基金,注重合作項目,更注重中長期的效益和回報。不同於以往股權投資7~10年的投資週期,絲路基金的投資期限能夠到15年或者更長的時間,可以滿足一些發展中國家中長期的基礎設施建設的資金需求。絲路基金首期資本金100億美元(首期注入的資本為美元),這主要是便於國內外投資者通過市場化方式加入進來,外匯儲備通過其投資平台出資65億美元,中國投資有限公司、中國進出口銀行、國家開發銀行亦分別出資15億、15億和5億美元。隨著"一帶一路"倡議的不斷推進,相信會有更多的資本進入。

2015年4月20日,絲路基金、三峽集團及巴基斯坦私營電力和基礎設施委員會在伊斯蘭堡共同簽署了《關於聯合開發巴基斯坦水電項目的諒解合作備忘錄》(以下簡稱《諒解備忘錄》),該項目是絲路基金註冊成立後投資的首個項目。根據《諒解備忘錄》,絲路基金將投資入股由三峽集團控股的三峽南亞公司,為巴基斯坦清潔能源開發、包括該公司的首個水電項目——吉拉姆河卡洛特水電項目提供資金支持。電力行業是巴基斯坦政府未來十年發展規劃中優先支持的投資領域,絲路基金首個對外投資項目落地巴基斯坦的電力項目,標誌著絲路基金開展實質性投資運作邁出了重要一步,而"中巴經濟走廊"建設是"一帶一路"建設的旗艦,表明絲路基金服務"一帶一路"建設的使命。從項目運營管理模式來看,卡洛特水電站計劃採用"建設—經營—轉讓"(BOT)模式運作,於2015年底開工建設,2020年投入運營,運營期30年,到期後無償轉讓給巴基斯坦政府;從項目融資方式來看,絲路基金投資卡洛特水電站,採取的是股權加債權的方式:一是投資三峽南亞公司部分股權,為項目提供資本金支持。在該項目中,絲路基金和世界銀行下屬的國際金融公司同為三峽南亞公司股東;二是由中國進出口銀行牽頭並與國家開發銀行、國際金融公司組成銀團,向項目提供貸款資金支持;從控制風險方面來看,通過股權加債權的方式,一方面可以通過股權鎖定長期投資的高額回報,獲取一定股份,參與公司治理,提高投資收益的確定性,另一方面可以通過債權獲取優先清償權,有助於控制風險。絲路基金不是援助性的,在一定程度上也是逐利的,因此絲路基金在服務"一帶一路"建設的同時要評估項目的風險,平衡好風險和收益之間的關係……

綜上所述,助力"一帶一路"倡議實施的各個資金提供機構之間不是各自為戰、相互競爭的關係,而是相互合作、協同發展的關係。為了推進項目融資的有效進行,我們要形成多方聯動的融資機制。"一帶一路"建設中的一般項目都需要債權融資和股權融資相配合,在充分發揮絲路基金的引導作用的基礎上,由絲路基金聯合其他投資機構比如亞投行共同投資股權,中投也可以附加參與一部分股權投資,啟動一些本來因缺少資本金而難於獲得貸款的項目,然後由中國進出口銀行和國家開發銀行跟進發放貸款,由商業銀行為項目參與企業提供銀行業務,積極引進民間資本參與項目建設,多方聯動,共同促進項目實施,有力的推動"一帶一路"倡議的實施。

請按此閱覽原文。

Editor's picks

Trending articles

By PwC

Foreword

Infrastructure development is crucial to improving connectivity and driving sustainable growth in ASEAN. It is important to identify the changing needs of each of these countries in order to leverage future opportunities and trends in infrastructure investments in the region.

This report is the second in a three-part Infrastructure Series. In the first report, Understanding infrastructure opportunities in ASEAN (2017), we discuss the existence of a widening infrastructure gap in the region, highlight the potential difficulties faced by countries in mobilising infrastructure investments, and examine measures that could potentially address these challenges. In addition, we introduce the future drivers that we believe will further increase infrastructure spending in the region.

In this second report, we take a closer look at how the identified drivers are shaping the pipeline of greenfield infrastructure projects in each ASEAN country. We also assess how the Public Private Partnership (PPP) project pipelines of these countries are shaping up in light of these driving forces.

The subsequent and final report of our Infrastructure Series, which will be published later in 2018, will cover infrastructure funding and financing, including developments in the funding landscape and alternative sources of financing.

We hope that you find our Infrastructure Series a useful resource that addresses some of the key issues that we as infrastructure practitioners grapple with. If you would like to discuss any of the issues raised here, please do get in touch with us.

Chapter 1: Infrastructure in ASEAN

All economies in ASEAN have been focusing their efforts on increasing both private and public sector investments in infrastructure. However, the region’s rapid growth has outpaced its infrastructure development, which has resulted in a huge need for infrastructure investments. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimated that ASEAN countries will require US$2.8 trillion in infrastructure investments from 2016 to 2030…

Transport

Asia Pacific is forecast to become the largest transport infrastructure market in the world with investments expected to increase from US$669 billion in 2016 to nearly US$1.2 trillion in 2025. Cumulatively, investments in transport infrastructure in Asia Pacific are expected to be almost US$9.0 trillion. This is due to the region’s diverse and difficult geography, rapid economic growth and increasing urbanisation, all of which culminates in an acute need to develop transport infrastructure and services.

Governments get ambitious

Governments in the region have identified transport infrastructure to be of strategic importance for their economic development and trade competitiveness. Given the rapid urbanisation and increasing mobility that many ASEAN countries are seeing, demand for transport infrastructure and more efficient transport networks is on the rise. This has placed pressure on governments to renew a commitment to transport infrastructure spending as part of their national development strategies.

Historically, there has been a focus on roads and bridges. Presently, 65% of projects under construction are roads and bridges. There were a total of 270 road and bridge projects in the past, accounting for more than 52% of the total transport projects. This emphasis is set to continue — of the total number of transport projects in the pipeline, 46% are roads and bridges, and 30% are rail.