Chinese Mainland

How Sri Lanka can capitalize on the Maritime Silk Road

By Pathfinder Foundation/EconomyNext.com

The Maritime Silk Road (MSR) and Economic Belt policy initiatives unveiled by President Xi Jinping in 2013 were identified as significant elements of an overall Chinese attempt to leverage China’s growing economic power and influence along its geographic boundaries.

The objectives of this enormous development initiative is to strengthen and expand co-operative interactions, create an integrated web of mutually beneficial economic, social and political ties, and ultimately lower distrust and enhance a sense of common security.

MSR : Concept and Direction

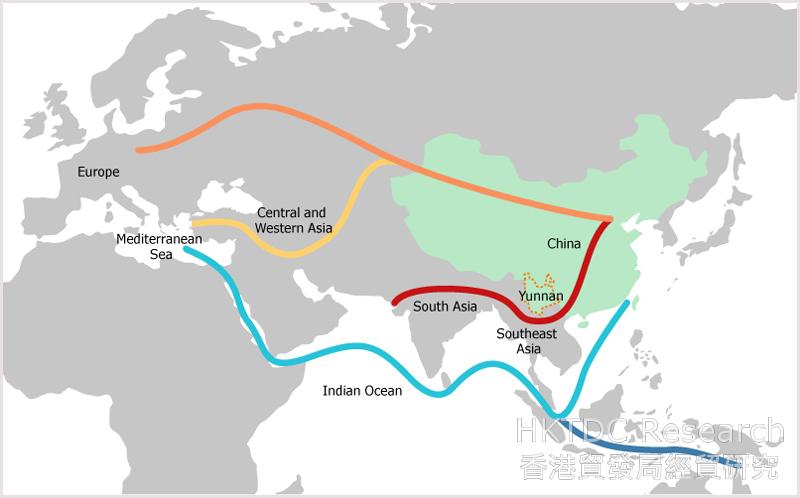

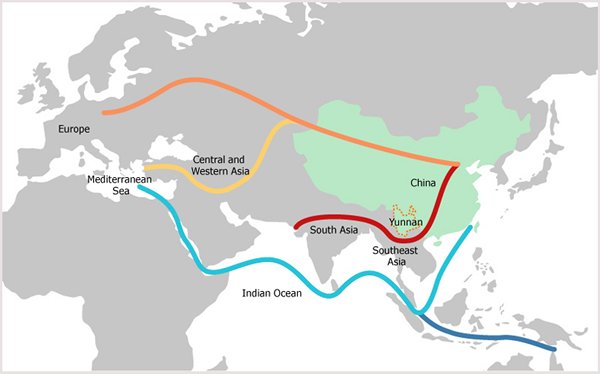

MSR and Economic Belt, also known as One Belt, one Road initiative, has envisioned the creation of a highly integrated, co-operative, and mutually beneficial set of maritime and land-based economic corridors linking European and Asian markets. The Belt and road run through the continents of Asia, Europe, and Africa, connecting the vibrant East Asia Economic circle at one end to a developed European economic circle at the other and encompassing countries with huge potential for economic development. The Silk Road Economic Belt focuses on bringing together China, Central Asia, and West Asia. The “Maritime Road” which is designed to extend from the China’s coasts through the South China sea, the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea, the Mediterranean Sea (through the Suez Canal), with stops in Africa along the way. After the official announcement by President Xi Jinping, the funding for the implementation of MSR and Economic Belt is to be modified through the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) amounting to $50 billion, $40 billion from the New Silk Road Fund, and the New Development Bank initiative between BRICS nations.

The scope and content of the One Belt, One Road initiative is breathtaking, and its goals are ambitious. A Chinese authoritative source once declared that the primary goal of this initiative is to promote and achieve five major goals: “policy coordination, facilities connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration and people-to-people contacts” among its constituent nation states. The initiative to jointly build the Belt and Road embraces the trend towards a multipolar world, economic globalization, cultural diversity and greater ICT application. It is also designed to uphold the global free trade regime and open the world economy. It is aimed at promoting orderly and free flow of economic factors, highly efficient allocation of resources and deep integration of markets. It is also aimed at encouraging the countries along the Belt and Road to achieve economic policy coordination, carry out broader and more in-depth regional co-operation and jointly create an open, inclusive and balanced regional economic co-operation architecture that will benefit all.

The Belt and Road Initiative aims to promote the connectivity of Asian, European and African continents and their adjacent seas. Established and strengthened partnerships among the countries along the Belt and Road, sets up multi-dimensional, multi-tiered and composite connectivity networks, which promote diversified, independent, and sustainable-balanced development among nations. The connectivity projects of the Initiative will help align and coordinate the development strategies of the countries along the Belt and Road, tap market potential in this region, promote investment and consumption, create demand and job opportunities and enhance people-to-people and cultural exchanges.

Perception of the West and the Indians

An article authored by Jacob Stokes, which originally appeared on the Times of India, states that, “the plans have strong financial backing, particularly through China’s vaunted AIIB, and the support of China’s political and economic elites. But huge stumbling blocks still remain, and could challenge China’s ability to realise its ambitions. While efforts to fill Asia’s infrastructure gap - estimated at $8 trillion through 2020 - are welcome, lax lending standards could undermine progress”. If nations use the funding to pursue illogical or unfeasible development projects related to One Belt, One Road, Chinese investments will suffer as debtors struggle to pay back loans. In addition, projects that come with unexpected environmental or human rights scandals could dampen Chinese efforts to upgrade port infrastructure along the route and create free trade zones which add trade capacity for participating nations. He also added that, “it is not yet clear how the maritime road will supplement existing shipping lines”.

Further, although Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi has stated that One Belt, One Road is “not a tool of geopolitics,” there is concern that China would attempt to turn economic co-operation into political influence. Doing so will require Beijing to overcome a number of difficult obstacles, primarily, managing great power competition with India, Russia, and the United States within Central Asia, South Asia, and the Middle East. Russia’s efforts to create a Eurasian Union, linking former Soviet states through economic co-operation, poses direct competition to China’s own integration strategy, even though Chinese-Russian relations are on the mend. India would have reservations about Chinese regional aspirations as well, since Beijing’s programs could hinder its own “Act East” and “Connect Central Asia” policies.

Chinese maritime expansion into the Indian Ocean - especially within ports that could serve as staging grounds for Chinese naval operations - only adds to India’s unease. Although the United States involvement in Central Asia is waning as its role in Afghanistan winds down, Chinese involvement across Eurasia, the Indian Ocean, and the Middle East will test Beijing’s ability to balance competition with co-operation - working with, than against, neighbours and global political powers.

Benefits and Pitfalls of Sri Lanka aligning with MSR

MSR itself will have many positive impacts on medium and longer term economic development of Sri Lanka as a country located strategically in the middle of the proposed Maritime Silk Road. Initially, it will attract infrastructure development oriented funding from the Chinese sources, such as Exim Bank, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, Silk Road Fund as well as private investors. Such improvements will provide the basis for flow of FDI from a large number of other investors from both the East and the West.

However, the Western and Indian analysts perceive and project the Chinese one-belt-one- road strategy as a security threat to its neighbours specially India, Sri Lanka’s closest neighbour. Historical animosity and suspicion between India and China is now being fueled by the latter’s emerging economic and military power. Issue in question is whether Sri Lanka should be the victim of rivalry between two countries which claim to be genuine friends of us.

Sri Lankan leaders, taking into consideration the complexities that exist in the geopolitical situation need to manoeuvre Sri Lanka - China and Sri Lanka - India relations to achieve a win-win-win situation.

This article was firstly published at EconomyNext.com.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Yunnan: A Planned Hub of Belt and Road

A Hub Reaching out to Southeast Asia

Under China’s Belt and Road Initiative, efforts are being made to promote economic policy coordination, orderly free flow of economic factors, highly efficient allocation of resources, and in-depth integration of markets between countries along the Belt and Road routes. In addition to the 60-plus countries involved, various provinces and cities in China are also taking proactive steps to complement the development of the Belt and Road. In the Vision and Actions on Jointly Building the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road released by the National Development and Reform Commission in March last year, it was pointed out that in advancing the Belt and Road Initiative, China will give full play to the comparative advantages of various regions in the country. It also stated that efforts will be made to “take full advantage of Yunnan’s geographic position to advance the construction of international transport links connecting with neighbouring countries”, with plans to build the province “into a hub reaching out to South Asia and Southeast Asia”.

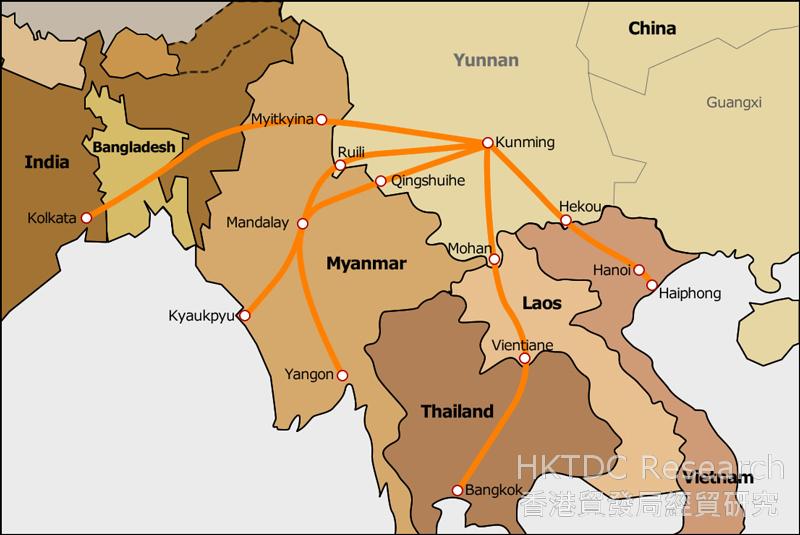

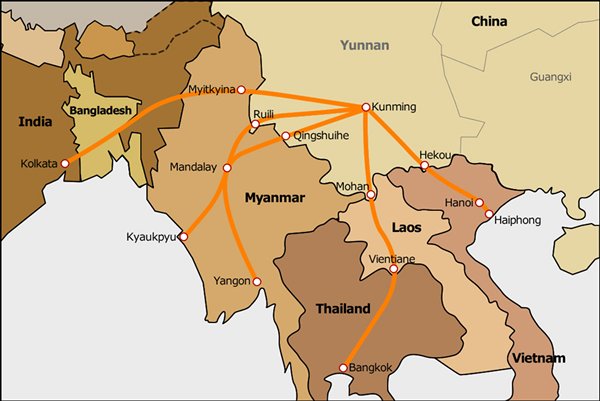

According to the Vision and Actions, the key cooperation directions for development of the Silk Road Economic Belt include from China to Southeast Asia, South Asia, and the Indian Ocean. Geographically, Yunnan is located at a key position in the land links between China and Southeast Asia. The province shares a common border of more than 4,000 kilometres with the three ASEAN countries of Myanmar, Laos and Vietnam, and is close to India, Bangladesh, Thailand and Cambodia. From Yunnan, the distance to the Indian Ocean through Myanmar is much shorter than via the Strait of Malacca. Hence, Yunnan is positioned as a “hub reaching out to South Asia and Southeast Asia” in the Belt and Road Initiative.

Yunnan’s Position in the Silk Road Economic Belt

From “Far-flung” to “Frontier”

Situated in the marginal regions of inland China, Yunnan occupies a “far end” position in terms of transport links. However, as China unfolds its Belt and Road strategy, Yunnan will evolve from its “far-flung” position to become a “frontier”, acting as a hub serving Southeast Asia and South Asia. Goods can travel by road from China’s coastal regions to the Yunnan provincial capital of Kunming and on to border ports including Ruili and Wanding. From there, they can travel south through Myanmar and on to the Indian Ocean. An expressway from Hangzhou in Zhejiang to Ruili in Yunnan has recently opened fully, greatly shortening the travelling time of land transport from China’s coastal regions to Myanmar. Hence, taking full advantage of Yunnan’s geographic position to construct a land-transport network will bring together the economic growth areas and markets of China, South Asia and Southeast Asia, improving the flow of resources and benefiting economic development.

In an interview conducted by HKTDC Research, representatives of the Yunnan Development and Reform Commission said that in building the Belt and Road, Yunnan will focus its efforts on playing up to its regional advantages. Action will be taken to construct an international passage linking China to the Indian Ocean and South Pacific Ocean by land, and to build an export-oriented industrial base. In these efforts, infrastructure construction and connectivity development will be prioritised.

Building a Transport Hub Linking China and Southeast Asia

To develop as China’s land-transport hub for Southeast Asia, Yunnan is set to devote efforts to strengthening ties with both inland regions and foreign countries. According to the Yunnan Department of Transportation, the province has built, or is upgrading, a number of routes serving inland regions, including a national-level expressway running from Kunming to Beijing (National Trunk Highway System No. G5). The Yunnan section of this expressway runs from Kunming to Yongren, with the section linking Panzhihua in Sichuan already completed and open to traffic. The Kunming-Yinchuan Expressway (G85) passes through Yibin in Sichuan after leaving Yunnan. The Yunnan section of the Kunming-Hangzhou Expressway (G56) is currently being fully upgraded to expressway. The Shanghai-Kunming Expressway (G60) runs through Qujing to Guizhou, and the Yunnan section has already been completed. The Kunming-Shantou Expressway (G78) traverses Shilin to connect with Xingyi in Guizhou, with the Yunnan section currently being upgraded to expressway. As for the Kunming-Guangzhou Expressway (G80) which passes through Guangxi, the Yunnan section has already been completed. From Kunming to Lhasa, the Yunnan section stretches 875 km, of which 477 km has been built into an expressway.

In the construction plan for transportation between Kunming and the Indochina Peninsula, a number of land routes are covered, including one running from Kunming to Hekou before joining Hanoi in Vietnam. Of this route, the Kunming-Hekou section covers 401 km, the Hekou-Hanoi section spans 264 km, and the Hanoi-Haiphong section totals 105 km. To date, only 30 km remain to be built into an expressway. It is estimated that, when completed, it will take just seven hours to drive from Kunming to Hanoi.

The Kunming-Bangkok highway starts from Mohan in Xishuangbanna, Yunnan and runs through Laos to Thailand. Of its 1,802 km, the China section takes up 683 km, with part of it being upgraded to expressway. The Laos section covers 229 km and the Thailand section covers 890 km.

Another important route on the drawing board stretches from Kunming through Ruili to Kyaukpyu (a deep-water Indian Ocean port) in Myanmar. The total length of this route is 1,922 km, with the Kunming-Ruili section covering 742 km and the Myanmar section totalling 1,180 km. According to the Yunnan Department of Transportation, the conditions of the roads from Ruili to Mandalay in Myanmar still have much room for improvement. The road conditions from Mandalay to Kyaukpyu are seasonal, that is, they might be blocked during the rainy season. Construction work has to be further advanced.

As for road construction along the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor, it is planned that a route will be built leading to Kolkata in India via Myitkyina in Myanmar, stretching a total length of about 2,597 km. The Yunnan section, running from Kunming to Houqiao, covers 704 km; the Myanmar section totals 504 km (incorporating the Stilwell Road); the India section covers 892 km; and the Bangladesh section amounts to 497 km. However, the Yunnan Department of Transportation pointed out that the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor has yet to reach the detailed planning stage.

Also on the drawing board is a passage similar to the Ruili-Kyaukpyu branch road. This route, with a total length of 1,746 km, runs from Kunming to Qingshuihe and links to Yangon after leaving the Chinese border. The length of the Kunming-Qingshuihe section is 661 km, and the Myanmar section is 1,085 km.

Roadmap of Yunnan’s Outbound Highways

Where rail link planning is concerned, the Pan-Asia Railway Network comprises the east, central and west lines. The east line stretches from Hekou in Yunnan to Vietnam, the central line runs from Mohan in Yunnan via Laos to Thailand/Malaysia, while the west line links Ruili in Yunnan with Kyaukpyu in Myanmar. The Yunnan section of the east line is reportedly under construction. Building of the central line has already made some progress, with China signing cooperation documents with Laos and Thailand at the end of last year. Construction is expected to commence soon.

According to reports, it was announced at the beginning of this year that a CITIC-led consortium, jointly formed by the CITIC Group of China, Chia Tai Group of Thailand and Yunnan Construction Engineering Group, had won the bid to undertake the industrial park and deep-water port projects at the Kyaukpyu Special Economic Zone in Myanmar. Further development of Kyaukpyu will help to advance the construction of transport infrastructure between Yunnan and Myanmar and promote economic, trade and logistics ties between the two places. In the longer term, once the route between China and Myanmar is opened, goods from the inland regions (especially those from southwestern China) will use it for exports to Southeast Asia, as well as for transhipment to other parts of the world via Indian Ocean ports.

In addition to transport hardware, the improvement and streamlining of customs clearance procedures is another focus in the upgrading of Yunnan’s land connections with Southeast Asia. According to the Yunnan Department of Transportation, the drop and pull transport mode is currently being used at the borders between China, Laos and Thailand. In future, upon the signing of a China-Laos-Thailand tripartite transport facilitation agreement, cross-border customs clearance will be made more convenient, but this may involve complicated issues such as documentations, licences and insurance.

Dianzhong New Area is a Focus of Development

In Yunnan’s drive to develop into a hub reaching out to South Asia and Southeast Asia and advance the construction of international transport routes connecting with neighbouring countries, its provincial capital Kunming plays an important role. According to the Kunming Development and Reform Commission, there are plans to turn the city into a transport hub linking China by land with South Asia and Southeast Asia, as well as a national logistics nodal city and a regional-level international logistics centre. However, according to the Yunnan Department of Commerce, the standard of the logistics industry in the province is not high and its development is somewhat dispersed. As Yunnan’s outbound road links gradually take shape, logistics services have much room to grow and upgrade.

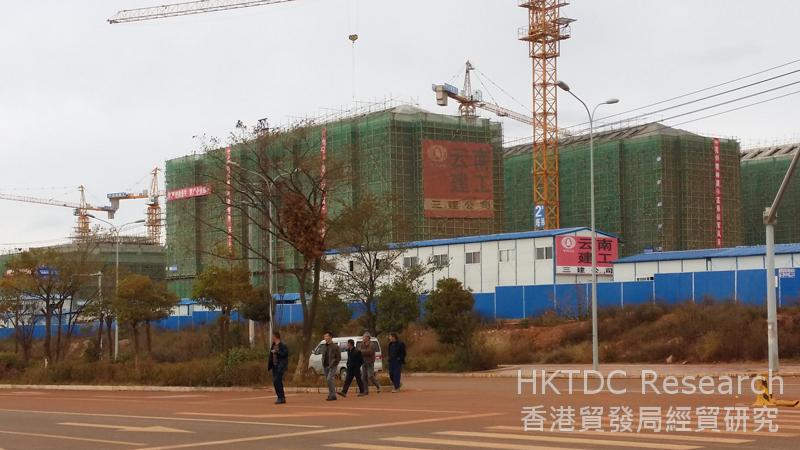

In September last year, the State Council officially approved the establishment of the Dianzhong New Area in Kunming, one of the major highlights of the city’s development plan. It was also proposed that construction of the Dianzhong New Area be designated as an important move in major initiatives and regional development strategies such as the Belt and Road and Yangtze River Economic Belt, as well as being a significant pivot in creating a hub in China that reaches out to South Asia and Southeast Asia.

Located on the east and west flanks of Kunming city proper, Dianzhong New Area is scheduled to become a modern urban area within 20 years. It will contain a number of industrial parks – such as an economic and technological development zone, and the Kunming airport economic zone – that aim to grow emerging industries and modern services. For example, the airport economic zone in the eastern section of the new area intends to develop airport-related industries and logistics services.

The new area will also be built into an export processing base serving South Asia and Southeast Asia. According to Suning Appliance Logistics Centre, which began operating in the new area last year, Phase I of the centre occupies an area of 40,000 square metres, and is projected to expand to 80,000 square metres in the future. The centre’s major function is to complement the distribution services of e-commerce operators, serving the whole of Yunnan province and parts of Sichuan. In the future, it is also possible that Kunming will be used as a distribution base to deliver goods to Southeast Asian countries such as Myanmar.

According to sources from Dianzhong New Area, the transport network of Kunming Airport is gradually expanding. Five logistics enterprises are already operating in the airport economic zone while more than 30 industry players are negotiating to make an entry. The new area hopes to place emphasis on developing airport logistics as well as aviation-related industries, such as airport cold-chain logistics dealing with fruits and vegetables from Yunnan and aquatic products from Southeast Asia. Many courier companies are also getting ready to make a foray into the airport economic zone, which is in the process of applying for permission to set up a comprehensive bonded zone. In addition, there are plans to convert the dedicated railway infrastructure of now-defunct coal-fired power plants into bulk goods yards, and bring together rail, road and air transport.

Air transport is mainly domestic oriented at present, mostly serving the Yunnan and southwestern regional markets. It is hoped that international markets will be developed next – for example, exports of fresh flowers from Yunnan and imports of seafood from Southeast Asia by air. It is also hoped that leading production enterprises which require air-transport services will be attracted to the new area in order to propel airport logistics and, in turn, advance the integrated development of industry and logistics. Players in related manufacturing industries and logistics services should take note of these developments and capture new business opportunities as they arise.

| Content provided by |

|

Editor's picks

Trending articles

‘Belt and Road’ Opportunities for Hong Kong

By Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce

In 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Central and Southeast Asia. During his visit, he had proposed joining hands to build a “Silk Road Economic Belt” and a “21st-Century Maritime Silk Road” (Belt and Road). Since then, this innovative concept of Belt and Road has attracted a great deal of attention from both China and even the rest of the world. Similarly, this concept has sparked discussions among industry insiders in Hong Kong. As an integral part of the Mainland, Hong Kong can play a role in the Belt and Road plan.

“Going Abroad”

Some target countries and regions are emerging economies or developing countries whose legal systems are not that sound. This might lead to challenges for investors. These host countries would usually impose higher tax rates on foreign investment, or in terms of international tax, e.g. definition of Permanent Establishment, they may disregard international practice, or even apply more stringent policies than the international common practice.

Chinese businesses “going abroad” might be treated unfairly, and thus could run into tax disputes. In this regard, we suggest that enterprises should think through the tax policy of host countries and multilateral tax regulations applicable to the “going abroad” projects, in order to minimize any tax burden.

Many developing countries along the Belt and Road roadmap have a less than favourable investment environment. Large-scale PRC enterprises may act as the leading force, jointly with other PRC enterprises, in an attempt the test out the unfamiliar investment environment.

Taking China-Belarus Industrial Park as an example, it will offer preferential taxation by the 10+10 formula to investors, i.e. exemption of 100% corporate income tax for the first 10 years from the date of registration in the park and 50% reduction of corporate income tax for the next 10 years of operation in the park. In addition, employees joining companies in the park also enjoy tax benefits, as well as “one-stop” services during the setup and post-establishment of the enterprises in the park. To date, six enterprises, including YTO Group, ZTE, Huawei, and China Merchants Group, have confirmed and signed an agreement to set up in the park. Around 10 other enterprises have indicated interest, and are considering the options of entering the park.

Hong Kong as a “Super-connector”

Despite financing from the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, Silk Road Fund, China Development Bank, and other institutions led by the PRC Government, financing in respect of Belt and Road related infrastructure remains a major shortfall – around US$8 trillion according to market estimates.

Currently, there are already some Hong Kong finance and insurance institutions who have actively participated in Belt and Road projects, and have utilized their experience and strength in the financial services sector. Through cross-border M&A project financing, construction project financing, international factoring, and the combined use of general debt, preferential debt, and other investment and financing combinations, enterprises are presented with a multitude of financing options.

On the other hand, due to its unique economic position and geographical location, Hong Kong plays a vital role as a super-connector in the Belt and Road roadmap. As an investment hub, the tax treaty benefit under the PRC-HK Double Taxation Arrangement would provide investors with higher tax efficiency.

When facing challenges arising from multi-locations operations, multiple currencies and multinational supply chains, enterprises can leverage Hong Kong’s position as a transport hub, international finance centre and window to the West. Doing so can raise enterprises’ international management standards, as well as expand their global market network. In reality, many Chinese enterprises have set up a finance platform in Hong Kong, or are targeting Hong Kong as a “going abroad” platform.

With the high profile of the Belt and Road policy, the “going abroad” of Chinese enterprises has already evolved into a mechanism that integrates economic, political and cultural factors. In the complicated external economic environment, there is an increasingly difficult international tax environment along with products, projects, investments and personnel “going abroad.” Properly handling these problems requires the wisdom and collaboration of entrepreneurs, governments and professionals.

This article is firstly published in the magazine The Bulletin of the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce (January 2016 issue). Please click here to view the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Belt and Road: Trade and Border Cooperation between Yunnan and Myanmar

In advancing its Belt and Road Initiative, China is giving full play to the comparative advantages of various regions in the country, with Yunnan province positioned as “a major hub reaching out to South Asia and Southeast Asia”. Yunnan will take full advantage of its geographic position to build an international passage from China to the Indian Ocean and South Pacific Ocean by land. Efforts will also be made to build an export-oriented industrial base and to develop the province into a regional-level international economic and trade centre for China, reaching out to South Asia and Southeast Asia.

In recent years, a number of export-oriented processing industries, including BAIC Yunnan Ruili Automotive and Chongqing Yinxiang Motorcycle, have set up in the border regions. As well as Kunming’s Dianzhong New Area, which is the focus of regional development, Yunnan will develop border economic cooperation zones with Myanmar and Vietnam - notably the China-Myanmar Ruili-Muse Cross-border Economic Cooperation Zone at the Myanmar border - in order to promote economic and cross-border cooperation in the border regions.

Myanmar: Yunnan’s Major Trading Partner

Yunnan’s trade with ASEAN jumped to US$14.3 billion in 2014 from US$6 billion in 2011, with exports making up about two-thirds of the value. ASEAN accounted for 48% of Yunnan’s external trade in 2014, up from 37% in 2011. Trade between Yunnan and Myanmar in 2014 accounted for 49% of the province’s trade with ASEAN, and almost 30% of the trade between China and Myanmar.

According to the Yunnan Department of Commerce, finished products such as the garments and household appliances exported by the province, mostly come from the coastal regions and account for about half of Yunnan’s exports to ASEAN. Traders carrying out business via Yunnan mainly conduct general trade, with border trade accounting for only about 12% of the total. In the past, border trade benefited from preferential policies on tariffs and VAT, but these concessions have gradually been removed in recent years. According to the Yunnan Department of Commerce, a number of manufacturers from the coastal regions have set up in Yunnan and the border cooperation zones in order to conduct export trade with Southeast Asia. However, since these export orders tend to involve small volumes and a large variety of product types, it is more convenient to conduct business through traders.

Yunnan’s Ruili port, bordering Myanmar’s Muse port, is China’s largest land port in terms of trade with Myanmar. For many years, the total value of import-export trade handled via Ruili port accounted for about 60% of Yunnan’s trade with Myanmar.

|

The Luoshiwan International Trade City in Kunming is the largest wholesale facility in the city. Housing 25,000 business operators engaged in wholesale and retail, Luoshiwan boasts a daily visitor flow of 250,000. Visitors include local people from Kunming, residents in neighbouring prefectures and cities, as well as traders with truckloads of goods from places such as Guangdong, Zhejiang, Fujian and Guizhou. Located next to Luoshiwan is an integrated logistics facility where goods from outside the province can be stored and then delivered door-to-door to buyers. Luoshiwan’s business model is similar to that of Yiwu in Zhejiang. According to a Luoshiwan representative, 70-80% of business operators in the trade city come from outside Yunnan, mainly from Zhejiang, Guangdong and Fujian. The majority are traders, although some are manufacturers. While wholesale mainly targets Yunnan and the southwestern region, it is estimated that about 20% of the business involves foreign markets, such as Laos and Myanmar. This business is conducted primarily in the form of border trade. Some ethnic products are also sold to India and Pakistan. According to the Luoshiwan representative, its growth is a result of the rising consumption levels in Yunnan in recent years. For instance, the trade city’s latest phase (Phase II) generally sells garments via brand-name stores, with the products on offer there of a considerably higher grade than those being sold in Phase I.

|

Development and Opening-up Experimental Zones Propels Growth of Border Areas

The State Council issued the Opinions on Several Policies and Measures Supporting the Development and Opening-up of Key Border Areas in January this year. It was advocated that steps will be taken to promote the development of priority industries in the border areas; support and prioritise projects to process, transform and utilise imported energy resources as well as projects to process imported resources in key border areas; develop export-oriented industry clusters; and look into the possibility of establishing a key border area industrial development fund. These policies indicate that the central and local governments are positively advancing industrial development in the border areas. In fact, before the above opinions were issued, Yunnan had already devoted considerable effort in recent years to implementing policies encouraging the development of the border areas.

Following approval by the State Council, two key development and opening-up experimental zones have been built in Yunnan’s border areas. The Ruili Key Development and Opening-up Experimental Zone was established in 2012, and the Mengla (Mohan) Key Development and Opening-up Experimental Zone was approved in July of last year. Meanwhile, efforts are continuing to promote cross-border economic cooperation zones in the hope of strengthening joint development with those Southeast Asian countries sharing the same border. Currently, there are four national-level border cooperation zones in Yunnan – in Ruili and Wanding (serving Myanmar), Hekou (serving Vietnam) and Lincang (approved in 2013 and also serving Myanmar).

The Ruili Key Development and Opening-up Experimental Zone is located in the Dehong Dai and Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture in the western part of Yunnan province bordering Myanmar. With Ruili city as its core, the experimental zone houses two category-one national ports, Ruili and Wanding, as well as the Ruili and Wanding national-level border economic cooperation zones. It is hoped that the Ruili experimental zone will become a China-Myanmar border economic and trade centre, as well as an important international land port for China’s southwestern region. Its primary role includes promoting opening up to the outside world; expediting the development of priority industries; accelerating the development of import-export processing zones, and international logistics and warehousing zones; strengthening and enhancing deep-processing industries involving such resources as jewellery and jade, quality timber, and natural rubber; and placing an increased emphasis on developing export processing industries reaching out to the South Asia and Southeast Asia markets.

A number of preferential tax policies are offered in the Ruili experimental zone. Newly established enterprises entering the zone, with the exception of those engaging in industries prohibited or restricted by the state, are entitled to a “five-year exemption and five-year reduction by half” of the local portion of their payable enterprise income tax. Under this concession, counting from their first year of generating income from production or operation, new enterprises will have the local portion of their enterprise income tax exempted for five years and reduced by half in the five years that follow. Where the labour market is concerned, it is estimated that about 60,000 to 70,000 Burmese workers are employed in Ruili, each earning a monthly wage of about RMB1,000. However, labour turnover is quite high. The Ruili experimental zone has also made some progress in attracting the entry of large enterprises, such as Chongqing Yinxiang Motorcycle and the BAIC (Beijing Automotive Industry Corporation).

|

BAIC began negotiations with a local private enterprise in Ruili in 2013 with regard to the setting up of a joint-venture project. With a total investment of RMB3.6 billion, the project has a planned production capacity of 150,000 vehicles upon completion in 2018. Phase I assembly line construction, with a planned capacity of 50,000 vehicles, began in July 2015 and is scheduled for completion by the end of this year. According to a representative of BAIC’s Ruili plant, negotiations on the project were successful thanks to the Belt and Road strategy, which allows the plant to target the Southeast Asia market. The plant can also benefit from the tax concessions offered by the Ruili Key Development and Opening-up Experimental Zone. BAIC started its export business a few years ago and today its products are sold to a number of countries, including Iran, Egypt, Russia and Ukraine. When prioritising export markets in Southeast Asia, BAIC’s first port of call is Myanmar, where the demand for automobiles is huge and second-hand Japanese cars are popular. BAIC plans to produce such auto models as pickup trucks designed specifically to cater to the Myanmar market, with a price point set at about RMB40,000, including provision for a good after-sale service. BAIC has now started to set up sales networks in Myanmar and, through the networks of its joint-venture partner in Yunnan, plans to open shops in Myanmar to sell vehicles and provide a maintenance service.

The parts and components required by BAIC’s Ruili production line are mainly delivered by road from Chongqing, a journey of about two to three days, as rail transport is not yet available. As a result, the transportation costs are rather high. However, many parts and components suppliers have shown interest in coming to Ruili to set up plants to supply the production line. Even when output reaches 100,000 automobiles, it is expected that only about 3,000 workers will be required, with BAIC currently cooperating with local technical schools to train the necessary staff. |

Promoting the China-Myanmar Cross-Border Economic Cooperation Zones

The Ruili Border Economic Cooperation Zone, situated in the Ruili Key Development and Opening-up Experimental Zone, covers an area of about six square kilometres. Located in the Ruili Border Economic Cooperation Zone, the Jiegao Border Trade Zone, covering an area of about 1.92 square kilometers, operates under a special customs supervision mode, whereby vehicles, goods and articles entering and leaving Jiegao from and to Myanmar are not required to make customs declaration to the Chinese authorities and are exempted from customs tariffs and import-related taxes. Goods and articles entering Jiegao from other parts of China are treated as exports once they cross the customs territory boundary. Jiegao is the logistics centre for border trade between China and Myanmar. It is also a gateway to Southeast Asia encompassing trade, processing, warehousing and tourism. To date, it has considerably bolstered production and trading in the jade and redwood furniture industries. Since the special customs supervision policy was implemented, Jiegao has made good progress in trade, warehousing and tourism and has become an important channel for goods and the flow of people between China and Myanmar.

The Jiegao Border Trade Zone has also boosted the development of Myanmar’s Muse region, which borders Yunnan. As a counterpart, Myanmar has set up the Muse Special Economic and Trade Zone, where a special customs supervision model, similar to that implemented in China, has been adopted. Drawing on the experience of establishing Jiegao, Yunnan is now looking into the feasibility of setting up the China-Myanmar Ruili-Muse Cross-border Economic Cooperation Zone. The Yunnan authorities are negotiating with Myanmar with regard to a proposition that each side allocates 100 square kilometres in order to establish a comprehensive cross-border economic cooperation zone, embracing export processing and assembly, imported resources processing, warehousing, logistics, finance and tourism.

| Content provided by |

|

Editor's picks

Trending articles

10 May 2016

China's One Belt One Road: Has The European Union Missed The Train?

By S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University

This Policy Report focuses on the overland routes that connect China to Europe via Central Asia and it aims to answer the question whether the European Union (EU) should engage China in the One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative. The expansion of the OBOR initiative is forcing China’s economic diplomacy to embrace a broader political and security engagement. While Russia and the United States are revising their roles in South and Central Asia, the EU has lost momentum.

This Policy Report addresses the need for the EU to:

- adopt a common voice to engage China’s OBOR initiative;

- promote stakeholder participation;

- coordinate crisis prevention; and

- avoid focusing only on short-term economic gains to attract China’s outbound direct investments.

The EU involvement with the OBOR initiative is adefining moment for Sino-European relations. In this respect, China has to:

- communicate a detailed road map on the OBOR initiative;

- allow local economic actors to access the bids for infrastructural projects;

- increase the role of private Chinese SMEs; and

- avoid relying on the OBOR initiative to export industrial overcapacity.

In this regard, the utilisation of the EU social and environmental best practices by Beijing and a renewed EU stance towards a “flexible engagement” with China could be mutually beneficial for fostering regional stabilisation and structural reforms in South and Central Asia.

Please click for the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

13 May 2016

China’s Belt and Road Initiative Motives, Scope, and Challenges

Published by the Peterson Institute for International Economics

Edited by Simeon Djankov and Sean Miner

For more than 2,000 years, China’s commercial ties with the outside world have been symbolized by the ancient Silk Road, which began as a tortuous trading network of mountain paths and sea routes that provided a lifeline for the Chinese economy. Now the leadership in Beijing is reviving the concept with an enormously ambitious plan to build and upgrade highways, railways, ports, and other infrastructure throughout Asia and Europe designed to enrich the economies of China and some 60 of its nearby trading partners. The potentially multitrillion dollar scheme, which Beijing calls the Belt and Road Initiative, has generated enthusiasm and high hopes but also skepticism and wariness throughout the region and in capitals across the world.

What are the motivations for China’s oddly and perhaps illogically titled initiative? (The “belt” refers to the land portion of the silk route—the Silk Road Economic Belt—and the “road” refers to the Maritime Silk Road.) Is China’s goal to serve as the altruistic equivalent of the US Marshall Plan, the massive post–World War II reconstruction of Europe by the United States? Or is it a plan to cement Chinese leadership and perhaps even hegemony in competition with the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the recently signed trade pact involving the United States, Japan, and 10 other countries on the Pacific Rim? One conclusion is certain, the world is paying attention when one country embarks on an elaborate effort to dramatically upgrade the infrastructure serving three-fourths of the world’s population, increasing their mutual economic dependence on China and each other. As big as China’s ambitions are, many obstacles stand in the way. If successful, China will be disrupting historical spheres of influence of many countries, most notably India and Russia, which regard the region as their neighborhood just as much as China regards it as its own. The record also suggests that ambitious plans to build infrastructure run into many logistical problems, from cost overruns to “bridges to nowhere” to corruption. If, on the other hand, China treads carefully, heeding warnings from history and the concerns of its neighbors, and transforms its initiative into a participatory exercise rather than a solo act, the whole world can benefit.

In this volume of essays edited by Sean Miner and Simeon Djankov, PIIE experts analyze the Belt and Road Initiative’s prospects, the challenges it poses, and China’s goal of furthering its economic, political, security, and development interests. They draw on lessons from past initiatives by multilateral development banks and the experience of the United States and United Kingdom in undertaking grand infrastructure projects. The authors find that the initiative presents both opportunities and risks for the United States, China’s neighbors, and the rest of the world.

Djankov assesses China’s true motivations behind this grand initiative. Miner analyzes the economic and political implications and the steps China can take to broaden the initiative’s benefits. Edwin Truman argues that China faces challenges in the way it governs the initiative and that it should redefine its role in multilateral development banks. Robert Z. Lawrence and Fredrick Toohey draw on historical examples to show that such initiatives must be complemented with institutional reforms and policies in countries where the projects are located. Otherwise pressure from profit-oriented firms can rapidly lead recipient countries into quicksand. Cullen S. Hendrix looks at the security implications and whether encroaching on India’s borders and Russia’s self-defined sphere of influence will cause China more harm than good. Finally, Djankov assesses how the initiative may affect the former Soviet Bloc countries, concluding that success will depend on China’s efforts to blend its goals with those of the governments there.

Please click here for the full publication.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

17 May 2016

China’s the Belt and Road Risk Assessment Issue

By Lidiya Parkhomchik, Eurasian Research Institute

In recent years China begun to seeking for a greater role for itself in the international order. Beijing’s intention to strengthen its global position caused launching a number of multilateral initiatives, namely, the Belt and Road Initiative, which includes the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road projects. The Belt and Road Initiative was launched to promote economic cooperation and cultivate closer ties with countries along the route. According to the Vision and Actions on Jointly Building the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road issued by the National Development and Reform Commission of China on March 28, 2015, the Belt and Road’s member-states need to improve the region's infrastructure and put in place a secure and efficient network of land, sea and air transportation, to establish a network of free trade areas that meet high standards and to deepen political trust (National Development and Reform Comission, 2015).

The Belt and Road project runs through 5 routes shaped in order to connect the continents of Asia, Europe and Africa. For instance, the Silk Road Economic Belt focusses on: (1) linking China to Europe through Central Asia and Russia; (2) connecting China with the Middle East through Central Asia; and (3) bringing together China and Southeast Asia, South Asia and the Indian Ocean. On the other hand, the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road focusses on using Chinese coastal ports to: (4) link China with Europe through the South China Sea and Indian Ocean; and (5) connect China with the South Pacific Ocean through the South China Sea (Hong Kong Trade Development Council, 2016).

It should be also mentioned that one of the reasons for the Belt and Road Initiative’s launching was Beijing’s intention to encourage Chinese firms to go overseas searching new markets or investment opportunities. In this regard, the Chinese governmental bodies focused on providing guidance and advice for domestic companies on doing business in the Belt and Road countries strongly advising to familiarize with a brief introduction to their investment and business environment.

According to the preliminary maps published by the official sources in China, the Belt and Road includes up to 60 countries, which cover the area of the ancient Silk Road. However, not all of them have political and economic stability. Since the Belt and Road range from Sri-Lanka to Syria, any Chinese company planning to trade with or invest in the country along the Belt and Road could face with various challenges, which may prevent China from expanding its influence abroad. Moreover, financial institutions such as $40 billion Silk Road Fund, which was established to provide a direct support to the Belt and Road Initiatives, so as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which was spearheaded by China, should be cognizant of the range of credit risks present in the Belt and Road countries (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2015). Therefore, the exploration of the possible risks and threats that could negatively affect the Belt and Road Initiative developments has become even more significant.

It is obvious that the Belt and Road countries vary dramatically on the issue of potential operational and credit risks. According to the risk assessment report, made by the Economist Intelligence Unit, which scored risks across ten different categories, including security, legal and regulatory, government effectiveness, political instability, tax policy, labour market, foreign trade & payments, financial, macroeconomic and infrastructure, Afghanistan and Iraq, which are beset by conflict, score the highest with regards to overall risk. However, the Central Asian countries such as Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, where the Belt and Road push is likely to be strong, are very close behind. (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2015)

It should be highlighted that Beijing considers the policy coordination between countries along the Belt and Road as an important guarantee for implementing the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road Initiatives. It is obvious that without enhancing high degree of mutual political trust it is impossible to fully coordinate the implementation of practical cooperation and large-scale projects within the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative. Taking into account the fact that the Initiative member states have various forms of government and specific features of political systems there is an essential need for the Chinese authorities to build a multi-level intergovernmental communication mechanism (National Development and Reform Comission, 2015), which would reduce political risks and help to avoid failure in attaining the goals that were set in the Belt and Road Initiative.

Therefore, the political risks scenario analysis become an integral part of the preparatory process for the Initiative implementation. There are various political risks scenario analyses performed by different research institutions such as the EIU. For instance, Kazakhstan’s political stability risks assessments include various scenarios reflecting political changes in the country in case of transfer of power and the first change in political leadership since Kazakhstan gaining its independent in 1991. The main aim of aforementioned scenarios is to understand will the newly elected leader of the country provide the proper level of governmental support required for large-scaled projects implemented in the framework of the Silk Road Economic Belt.

Actually, Kazakhstan has been the biggest recipient of Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in the former Soviet Union, receiving a total of $22 billion in investment from 1991-2013. As of the end of 2014, China’s total stock of FDI to Kazakhstan exceeded $7.5 billion. Moreover, new packages of economic deals totaling $14 billion and $23 billion were unveiled in December 2014 and in March 2015 respectively. (Hong Kong Trade Development Council, 2015) Therefore, it is quite important for Beijing to minimize political risks and protect its overseas direct investment having governments’ guarantee that they will not change the outcome of a previously signed agreements.

In conclusion, it is clear that without proper evaluation of possible operational risk over the Belt and Road initiative implementation it would be impossible for Chinese side (governmental bodies or private companies) to ensure good business planning process. For instance, despite the fact that at the official level all Central Asian countries welcome China’s the Silk Road Economic Belt proposal, there are some economic and political concerns as well. Actually, political elites and security experts in much of Central Asia are aware that China’s growing economic presence can lead to Chinese dominance or interference in regional affairs. (Lain, 2014) Therefore, even strong financial support of the Silk Road Initiative proposed by Chinese President Xi Jinping could not guarantee successful implementation of the project, especially, in the countries with high operational risks.

Please click here for the full publication.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

20 May 2016

Comprehensive Planning to Support the Industries - Seize the Opportunities Arising from the “13th Five-Year Plan” and the “One Belt and One Road” Initiative

By Martin Liao (Legislative Council Member, Commercial (Second) Functional Constituency)

Last month, I mentioned in this column that this year’s Policy Address has set a right direction to value the “13th Five-Year Plan” and the “One Belt and One Road” Initiative. The right direction shall be followed by the Hong Kong Government’s launching relevant work as soon as possible, the key of which lies in whether the Hong Kong Government has the needed vision to set up objectives and to implement the blueprint.

As our country deepens the opening-up policy and reform of financial sector, Hong Kong, being the largest offshore RMB (“CNH”) center, is well positioned to develop into the world’s most important offshore RMB (“CNH”) price fixing center. With China integrating with the global market, the Hong Kong government should consider expanding and extending the interconnectivity model to new asset classes, as well as constructing the most effective cross-market interconnectivity platform, so as to develop a local market that converges domestic and foreign products. New platforms for fixed-income and currency products, commodities and bonds can be set up to establish benchmark prices, while risk management tools can also be developed to complement the existing equity and derivatives business. On the other hand, the huge capital requirement for the infrastructures of the “One Belt and One Road” Initiative alone is estimated at USD 1.04 trillion. Hong Kong is fully competent to become its “financing center”, acting as the primary multichannel financing hub for companies of the countries along Belt and Road. Deplorably, the Hong Kong Government has not shown the vigor to set up these fore-mentioned objectives in the Policy Address.

Following up with the right direction of the Policy Address

Regarding the development of bond market, Hong Kong’s financial industry can now leverage on the capital requirement from the “One Belt and One Road” Initiative and develop into a multi-channel financing center for financial products like sukuk. As a matter of fact it was mentioned in the Policy Address that Hong Kong is aspired to achieve the relevant objective. The problem is that Hong Kong’s bond market is substantially lagging behind. While the Hong Kong Government had acknowledged that Hong Kong must establish a liquid and active bond market many years ago, most bond products are only focusing on exchange fund notes, or fund gathering by bond issuance in the name of specific statutory bodies. These do not match up with our status as an international financial center. It is a pity that there is no sign of any powerful measure to drive any breakthrough in this bottleneck of our bond market in the Policy Address. In the budget delivered by the Financial Secretary, it was only mentioned that the Hong Kong Government would roll out the third round of sukuk in a timely manner; nothing about how to deepen development in the bond market was touched upon. In fact, the “financial industry” was only mentioned in four short paragraphs in this year’s Policy Address, and they are separated from those about the “13th Five-Year Plan” and the “One Belt and One Road” Initiative, as if there is no connection amongst them whatsoever. Had the Hong Kong Government stood up high enough, it would actually be able to recognize that full-scale development is only possible if industrial development is combined with the opportunities arising from the “13th Five-Year Plan” and the “One Belt and One Road” Initiative.

Meanwhile, “financial technologies” have been developing rapidly in recent years. Accelerated advances are noted in the scopes of payment, financing, investment and risk management, etc. Hong Kong as an international financial center could have been well-positioned to grow into a leading financial technology hub, just like New York and London. However, due to the inability to enact local laws and regulations timely with emerging innovative business models, progresses in mobile phone wallets, P2P loans and crowdfunding now all fall much behind other cities, and our “financial technologies” are only developing at a snail’s pace.

A balance to be stricken when developing financial technologies

At the moment, amendments to the laws have been made for developments in financial technologies in advanced economies such as the US, the European Union, Singapore and Japan, etc. In contrast, the three-month old Payment Systems and Stored Value Facilities Ordinance (Cap 584) is the only legislation in Hong Kong that is relevant to financial technology. In terms of emerging financing models such as internet crowdfunding and P2P loans, operators of loan platforms must be Money Lenders Licensees according to Hong Kong law, which has created much hindrance to relevant businesses. However, the issues that laws are not catching up with development are not dealt with in the Policy Address. If Hong Kong is truly developing “financial technologies”, then “the Steering Group on Financial Technologies” should appropriately loosen laws and regulations, while at the same time meticulously protect the interests of investors, such that a reasonable balance between loosening laws and protecting investors’ interests can be stricken. With such a basis in place, financial technologies will be able to grow orderly and healthily. Based on the existing legal framework of Hong Kong, a more suitable path for operation is to categorize clients of emerging financing models such as crowdfunding and P2P internet lending as professional investors. And in early March of this year, the industry has announced the launch of Hong Kong’s first-ever P2P crowdfunding platform for professional investors.

The problem of laws failing to catch up with development is also troubling the innovative technology sector. Admittedly, the unprecedentedly “generous” proposal of a 4.7 billion-dollar investment into innovative technology for scientific research, start-ups and technological application in this year’s Policy Address is a very good initiative. However, the support does not seem to be strong enough, and complementing policies such as legal issues are yet to be properly dealt with. While the 2 billion dollars setting aside for the “inno-tech fund” will be upped to 6 billion after matching with private venture capital funds, the amount is minimum compared with major technology nations which chip in hundreds of billions a year. The US, for example, invested USD 465 billion into the national research and development in 2014, 307.5 billion out of which was contributed by enterprises. Contrarily, private corporate contributions in Hong Kong have always been on the low side, resulting in the local research and development expenses only representing 0.73% of the GDP. To encourage companies to invest more resources in research and development, the Hong Kong government should offer tax incentives to technology development sectors such that they could enjoy tax deductions in research, personnel training and purchasing high-tech equipment. On the other hand, tax-free period and lowered profits tax can also be considered for startups in technological research.

The innovative technology industry has to be supported by laws and regulations

In fact, when the Chief Executive discussed with some young entrepreneurs of the innovative technology industry at a forum earlier on, it was mentioned that there are too many constraints in Hong Kong’s system of laws and regulations, which have been dragging the development of the innovative and technology sector. Examples of internet finance, internet car-calling services, auto-pilot driving technology etc. were raised to show where the real issues lie. If the Hong Kong Government advocates innovative and technology industry but allows hindrance to arise from outdated laws without actively managing the conflicts between new and old business models, I am afraid that good intentions would prove to be fruitless in the end.

With limited space in this column, I am only able to select a few examples to encourage the Government to pace up in perfecting its plans and to do its best to actualize all the relevant measures. I hope the government can take practical steps to lead and to support all the sectors of our society, seize the new opportunities in economic development and establish a strong foundation for Hong Kong’s continual prosperity and stability. I believe these are also the expectations of the general public.

This article was firstly published in the magazine CGCC Vision 2016 April issue. Please click here to view the full article.

(Remark: This is a free translation. For the exact meaning of the article, please refer to the Chinese version.)

Editor's picks

Trending articles

23 May 2016

The Belt and Road Initiative: 65 Countries and Beyond

By Fung Business Intelligence Centre

It has been a year since the Chinese government unveiled the official action plan for the Belt and Road Initiative. With new developments emerging all the time and more information available, it is necessary to have an up-to-date wrap-up on how the Initiative has progressed. One common confusion is which countries are exactly included in the Initiative as the Chinese government has never announced an official list. A Chinese report, released by the China International Trade Institute in August 2015, identified 65 countries along the Belt and Road that will be participating in the Initiative. Together, the countries along the Belt and Road will create an "economic cooperation area" that stretches from the Western Pacific to the Baltic Sea. According to our computation, these 65 countries jointly account for 62.3%, 30.0% and 24.0% of the world’s population, GDP and household consumption, respectively, today.

It is worth noting that, the Initiative should be taken as an open platform for all parties that are willing to contribute to global connectivity. As the official action plan for the Belt and Road puts it, "The Initiative is open for cooperation. It covers, but is not limited to, the area of the ancient Silk Road. It is open to all countries, and international and regional organizations for engagement…"

And Chinese President Xi Jinping has reiterated in many official occasions that the Initiative is an open, diversified and win-win project poised to bring huge opportunities for the development ofChina and many other countries. The Fung Business Intelligence Centre has in the past year collected a list of those other countries that have participated or have showed interest in the Initiative, through joining the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), developing transport infrastructure in collaboration with China, or through many other forms of cooperation. In this way, we have identified 48 such countries which are not covered in the 65-country list above but are likely to become active participants in the Belt and Road in the future.

Please visit the Fung Business Intelligence Centre website for the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

26 May 2016

The Belt & Road Initiative – A Modern Day Silk Road

By Norton Rose Fulbright

Introduction

The Belt & Road Initiative (B&R) is without a doubt the most ambitious, strategic interconnected infrastructure initiative devised in recent memory.

What?

Launched by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013, the initiative aims to connect major Eurasian economies through infrastructure, trade and investment. It will see a RMB1.5 trillion infrastructure investment pipeline1 stretching over 10,000 km over more than 60 countries with a total population of 4.4 billion2 and 40% of global GDP3 across Asia, Europe, the Middle East and Africa, and cover projects across the infrastructure and energy sectors from small scale renewables to large scale integrated mining, power and transport projects. After its announcement in 2015, over 1400 contracts worth over US$37 billion were signed by Chinese companies in the first half of 2015.4

Full details of both the project pipeline and the specific requirements for a project to qualify as a B&R project are still not fully certain. What is clear is that the potential opportunities for infrastructure investment are immense.

For any host country or investor interested in infrastructure in B&R regions, Chinese capital cannot be ignored. Tapping it can be difficult but a foreign investor who can navigate the issues involved is potentially unlocking the key source of capital and equipment for the B&R regions’ major projects over the next fifteen years.

Where?

The Belt & Road Initiative has two main elements: the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road.

The Silk Road Economic Belt will be an overland network of road, rail and pipelines roughly following the old Silk Road trading route that will connect China’s east coast with Europe via a new Eurasian land bridge. 5 regional corridors will branch off the land bridge, with Mongolia and Russia to the North, South East Asia, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh to the South, and central Asia, West Asia and Europe to the West.

The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road is a planned sea route with integrated port and coastal infrastructure projects running from China’s east coast to Europe, India, Africa and the Pacific through the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean.

The geographic scope of the Belt & Road Initiative is fairly fluid and on some interpretations has also been extended to Australia and the UK.

A snapshot of the land corridors and a map showing both the Belt and the Road is set out……

This article was first published by Norton Rose Fulbright and is reprinted here with their full permission.

Please click here for the full article and related information.