Philippines

Bridge-building initiative helps Beijing and Manila get over the troubled waters of the South China Sea dispute.

While recent extreme weather events mean that the Philippines' massive infrastructure development programme may have to be re-designated as 'Re-build, re-build, re-build,' they certainly won't suffice to derail the key projects already commissioned in any significant way. Nor will they undermine the dramatically improved relationship between the country and China, a relationship that, in the past, was more strained than productive. Now, though, against the ever-expanding backdrop of the mighty Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the two countries are committed to building bridges. Quite literally.

As the damage caused by recent super-typhoon Mangkhut underlines, the Philippines is more vulnerable than most when it comes to incidences of extreme weather. As an archipelagic country, made up of more than 7,600 islands, building and maintaining bridges is an essential element in its economic development. The devastation left behind by the storms and typhoons that all too frequently strike the country – particularly in the case of its fragile bridges and viaducts – is made all the worse by the fact that the country still has far fewer such structures than it really needs.

There are, for example, only 19 bridges spanning the 27km-long stretch of the Pasig River that wends its way through Manila, the national capital. By comparison, the 13km of the Seine River in Paris is spanned by 37 such structures during the course of its meanderings through the French capital.

With this infrastructural shortcoming also a feature of many of the Philippines' other major cities, weather damage aside, extreme traffic congestion is now endemic, while bottlenecks caused by the restricted number of crossing points are commonplace. To try to remedy this, during July 2016-June 2018 the government completed retrofitting / strengthening work on 642 bridges, together spanning more than 29km. Some 939 bridges, spanning about 40km in total, were also wholly refurbished, while 204 new bridges (8km in all) were constructed. This, though, is only scratching the surface.

Given the immense costs involved in wholly upgrading the country's connectivity and transport infrastructure, it was inevitable that China would emerge as the only viable source of investment. Fortunately, the country's needs seem to be very much in line with the aims of the BRI, China's ambitious international infrastructure development and trade facilitation programme.

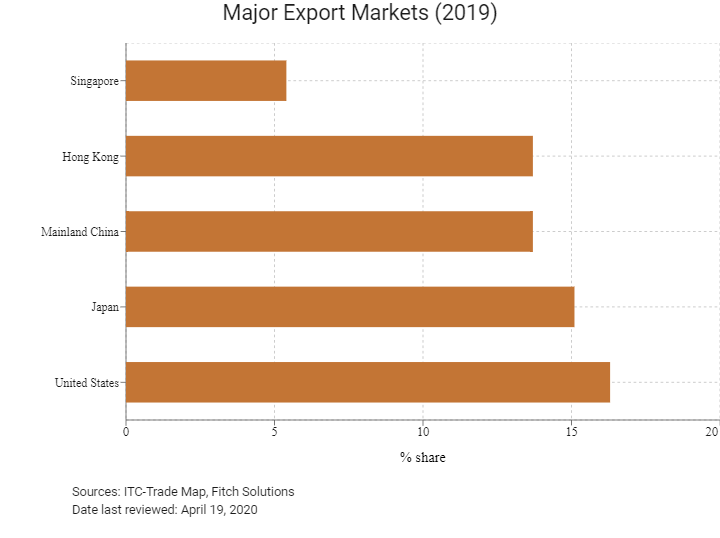

From China's point of view, the Philippines has a clear role to play in the bigger BRI picture. Most obviously, with a population in excess of 104 million, it is a ready market for Chinese exports, with its status as one of the fastest-growing economies in the ASEAN bloc only likely to enhance its allure. Improved connections and, consequently, improved relations would only ease access to this market.

On top of that, there is the country's geographical significance. China has already earmarked the Port of Davao, some 946km to the southeast of Manila, as a key stopping-off point and consolidation hub for the planned expansion of its trade in Southeast Asia and the South Pacific. To that end, it is committed to funding the redevelopment of the port as part of its wider investment commitment to the Philippines.

To date, China has pledged to back large-scale Philippine infrastructure projects to the tune of US$7.34 billion. This, though, is only part of the broader $24 billion agreed during the 2016 state visit to Beijing by Rodrigo Duterte, the President of the Philippines. Tellingly, since Duterte took office in May 2016, there has been a massive 5,682% increase in Chinese investment in the Philippines.

In more specific terms, earlier this year, China delivered on its pledge to provide PHP4.13 billion (US$78 million) of funding for two bridges on the Pasig River, with work beginning on both in July. The first project is actually a replacement for the 506-metre Estrella-Pantaleon bridge that connects Makati City and Mandaluyong City. The second is the all-new 734-metre Binondo-Intramuros Bridge, which will connect two of Manila's most historic districts.

More recently, in late September, the Chinese government agreed to finance and construct the PHP1.5-billion Davao River Bridge-Bucana, part of the 18km Davao City Coastal Road Project. At the same time, China also signed off on a $13.4 million grant for a feasibility study on plans for the massive Panay-Guimaras-Negros bridge project.

Financing for these projects is mainly being provided via the China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA), which only opened its doors in April this year. Despite its relatively recent establishment, the Philippines has already submitted 12 prospective big-ticket infrastructure projects to the agency for consideration. These are believed to include the Luzon-Samar (Matnog-Alen) Bridge; the Dinagat (Leyte)-Surigao Link Bridge; the Camarines Sur-Catanduanes Friendship Bridge; the Bohol-Leyte Link Bridge; the Cebu-Bohol Link Bridge and the Negros-Cebu Link Bridge.

With relations between China and the Philippines at a high point, despite the still-simmering South China Sea territorial disputes, it seems safe to assume that many of these projects will be greenlit. Indeed, it has been widely anticipated that Xi Jinping, the Chinese President, will give his formal assent to the proposals during his state visit to the Philippines later this year.

Marilyn Balcita, Special Correspondent, Manila

Editor's picks

Trending articles

Concerns over China's geopolitical intentions remain a challenge for Belt and Road projects in Southeast Asia.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has not moved quite as quickly in Southeast Asia as it has in South or Central Asia. This is partly down to ongoing tensions in the South China Sea, which have raised concerns among some countries in the region as to China's geopolitical intentions.

At present, the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is caught between these concerns and a desire to enhance its already strong trade relations with China. Overall, there is a recognition that the region would benefit from BRI-driven investment, with the Asian Development Bank maintaining US$1 trillion needs to be spent on infrastructure development by 2020 just to maintain current growth levels.

Xue Li is the Director of International Strategy at the Beijing-based Chinese Academy of Social Sciences' Institute of World Economics and Politics. Outlining the challenge facing the BRI, he said: "We haven't done enough to attract countries in Southeast Asia. On the contrary, their level of fear and worry toward China seems to be rising."

For Southeast Asia, the Singapore-Kumming Rail Link is something of a test case. This high-speed link will run through Laos, Thailand, and Malaysia, before terminating in Singapore, a total distance of more than 3,000km. To date, though, not everything is going the way China might have preferred.

In Laos, construction has been delayed. It is also likely that all of the work will have to be paid for by China, as Laos cannot afford the $7 billion required. In Thailand, meanwhile, negotiations have broken down. The Thais now want to build only part of the line – short of the border with Laos – and finance it themselves without Chinese involvement.

As to which company will build the Singapore-Malaysia stretch, that will be decided next year, with Chinese – as well as Japanese – firms emerging as the current frontrunners. Across the board, though, there is unhappiness at what is considered excessive demands and unfavorable financing conditions on the part of the Chinese. Back in 2014, Myanmar pulled out of the project, citing local concerns over the likely impact of the project.

A similar situation has now arisen in Indonesia. The $5.1 billion Jakarta-Bandung High-speed Railway Project, seen as an early success for the BRI, may now require significantly more funding. Indonesia is also unhappy at what it terms 'incursions' into its waters by Chinese fishing boats. It is, however, trying to downplay their significance as a 'maritime resource dispute' in a bid not to deter Chinese investment in the country. The Philippines is, by comparison, less conciliatory, largely because China is not one of its key trading partners. At present, the Philippines and Vietnam are the ASEAN nations most cynical with regards the ultimate intentions behind the BRI.

Singapore, a country with no direct stake in the South China Sea, remains strongly committed to the Initiative. In March this year, Chan Chun Sing, Minister in Prime Minister's Office, emphasised the importance of BRI as a means of improving links with China and its near neighbours.

He said: "The BRI represents a tremendous opportunity for businesses in Singapore – as well as in the wider Southeast Asian region – to work more closely with China. The more integrated China is with the region and the rest of the world, the greater the stake it will have in the success of the region. The more we are able to work together, the more it will bode well for the region and the global economy."

In line with this, this year has seen a number of Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) signed between China and Singapore. Back in April, one such undertaking was signed between International Enterprise Singapore (IES) and the state-owned China Construction Bank. Under the terms of the memorandum, $30 billion is now available to companies from both countries involved with BRI projects. At present, the two organisations are in discussion with some 30 companies with regards to developments in the infrastructure and telecommunications sectors.

In June, an additional MOU was signed between IES and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China. This has seen a further $90 billion earmarked to support Singapore companies engaged in BRI-related projects.

Ronald Hee, Special Correspondent, Singapore

Editor's picks

Trending articles

With Beijing-Manila ties at their most cordial, the Belt and Road Initiative is helping cement the countries' partnership.

As with many of the most successful Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) infrastructure-redevelopment projects, many of China's investments in the Philippines advance the programme's overall objectives while also meeting key local needs. A prime example of this is the mainland's huge contribution to tackling the water-management issues that have long confounded Manila, the Philippines' capital.

Already deemed a priority by Rodrigo Duterte, the Philippines President, and a key component of his massive Build, Build! infrastructure initiative, China agreed to underwrite the costs of two of the related projects late last year. This saw the Beijing-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the World Bank each sign off on loans of US$207.63 million for the Metro Manila Flood Management Project, with the balance of US$84.74 million being met by the Philippines government. At the same time, China also agreed to provide the US$234.92 million required to initiate the New Centennial Water Source-Kaliwa Dam project (NCWSP).

In terms of water management, Metro Manila suffers from two seemingly contradictory problems, having both too much and, on occasion, too little. This sees the city regularly subjected to serious flooding, often with tragic consequences for many of its residents, while it also struggles to meet the growing demand for safe drinking water occasioned by the region's ever-expanding population. It is hoped that the two China-backed projects will help to alleviate both of these problems.

In terms of the first, the Metro Manila Flood Management Project, this will entail a substantial upgrade to 36 of the region's pumping stations, while an additional 20 will be constructed from scratch. It will also involve a major overhaul of much of the supporting infrastructure along the region's primary waterways.

In total, work on the project will extend across a 29 sq km site. Once completed, it is expected to eliminate the danger of flooding for some 210,000 local households, benefitting about 970,000 people in all.

The first phase of the project, which will see five existing pumping stations substantially upgraded, is expected to get under way this year. At present, details of the required engineering work are being finalised, with procurement work set to be completed by the end of June. Construction proper will then begin in the autumn, with a scheduled end date early in 2020.

The project overall is aiming for a May 2024 completion date. From a local angle, construction will be overseen by the Manila Development Authority, with the National Housing Authority and the Social Housing Finance Corp also playing supervisory roles.

In the case of the NCWSP dam, it is hoped that this will bring an end to the capital's water shortages. To this end, the project will see the construction of a low dam with a discharge capacity of 600 million litres per day and a 27.7-kilometre raw water conveyance tunnel with a capacity of 2.4 million litres per day.

At present, the Philippine authorities are considering bids from three mainland construction companies, one of which, under the terms of the loan, will be appointed as the principal contractor on the project. The three shortlisted contenders are China Engineering, Power China and a joint bid from Guangdong Foreign Construction and Guangdong Yuantian Engineering. Once due diligence has been completed, the winning bid will be announced by the Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System, the Philippine government body with oversight on the project.

Scheduled to be completed in 2023, there is considerable pressure to ensure this particular project is not subject to any delays. This is largely down to the fact that the Angat dam, the source of 93% of the capital's water supply, will be unable to meet the growing demands of the city's population within eight years. Should the NCWSP encounter any major obstacles, Manila's taps running dry could become a very real possibility.

While the benefits to the Philippines represented by these two projects are clearly apparent, the upside for China is less immediately tangible. The new partnership between the two countries, however, has helped patch up a relationship that has more than occasionally been a little fraught. It has also succeeded in reducing the long-simmering tensions over the South China Sea, with the two countries now working more towards jointly administering and exploiting this particular stretch of the Pacific Ocean, rather than competing for ownership.

The thawing of relations has also already substantially improved bilateral trade, while the boost to the Philippine economy expected to result from the many China-backed infrastructure projects will doubtless provide a ready consumer market for an increased level of mainland exports. At the same time, this new co-operation is also expected to give China access to improved maritime trade via a number of the Philippines' hub ports.

Marilyn Balcita, Special Correspondent, Manila

Editor's picks

Trending articles

The Hong Kong Mass Transit Railway Corporation’s MTR Academy offers the railway’s best experiences and practices for supporting Belt and Road rail developments, says Academy President Morris Cheung. The MTR has a literal and figurative “track record” says Valentin Reyes of Manila’s Light Rail, while Hungary’s MAV learns from MTR’s financial sustainability and service.

Speakers:

Valentin Reyes, HSEQ Director, Light Rail Manila Corp

Morris Cheung, President, MTR Academy

Ilona David, President and CEO, MAV Zrt

Related Links:

Hong Kong Trade Development Council

http://www.hktdc.com

HKTDC Belt and Road Portal

http://beltandroad.hktdc.com/en/

GDP (US$ Billion)

330.91 (2018)

World Ranking 40/193

GDP Per Capita (US$)

3,104 (2018)

World Ranking 133/192

Economic Structure

(in terms of GDP composition, 2019)

External Trade (% of GDP)

68.6 (2019)

Currency (Period Average)

Philippine Peso

51.8per US$ (2019)

Political System

Unitary republic

Sources: CIA World Factbook, Encyclopædia Britannica, IMF, Pew Research Center, United Nations, World Bank

Overview

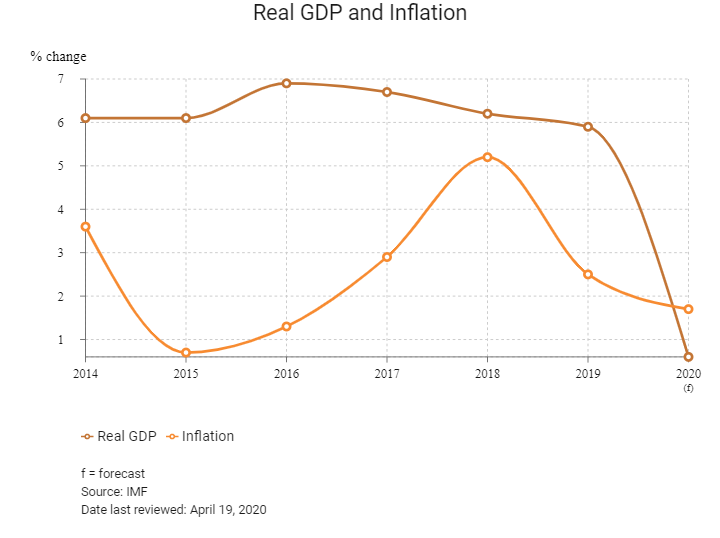

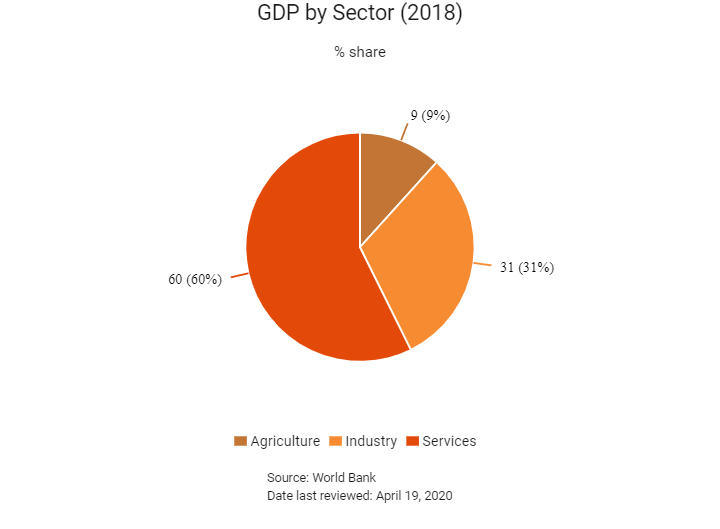

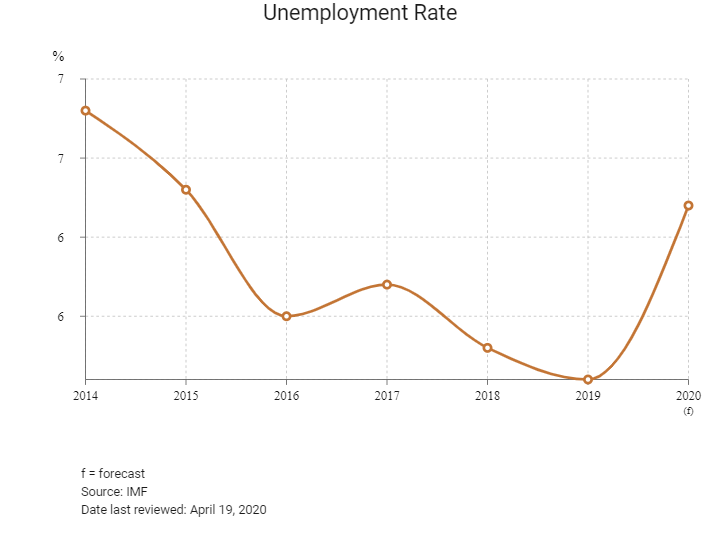

The Philippines has one of the most dynamic economies in the East Asia and the Pacific region. With increasing urbanisation, a growing middle income class, and a large and young population, the Philippines' economic dynamism is rooted in strong consumer demand supported by improving real incomes and robust remittances. Business activities are buoyant with notable performance in the services sector (including business process outsourcing), real estate, and finance and insurance industries.

Sources: World Bank, Fitch Solutions

Major Economic/Political Events and Upcoming Elections

June 2016

Rodrigo Duterte was elected president and announced a hard-line crackdown on drugs. He also suggested that he might pivot from the United States to Mainland China.

May 2017

Martial law was imposed on the island of Mindanao after fighting erupts between security forces and Islamic State-linked militants.

May 2018

Barangay elections were held on May 14, 2018.

May 2019

The 2019 Philippine general election was held on May 13, 2019. The winners took office on June 30, 2019, midway through President Rodrigo Duterte's six-year term. The election saw 12 seats in the House of Representatives, as well as all seats at the senate, provincial, city and municipality level contested.

September 2019

In September 2019, Philippines reformed the corporate tax system through the Corporate Income Tax (CIT) and Incentives Rationalization Act (CITIRA), which would reduce CIT from 30% to 20% over a 10 year period as well as introduce specific tax incentives for capital expenditure and labour up-skilling.

December 2019

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) approved a USD200 million loan for the preparation and execution of various development projects in the Philippines. The loan would support detailed engineering design of the Bataan-Cavite Interlink Bridge Project and the Metro Rail Transit Line 4 linking Ortigas in Metro Manila to Taytay in the province of Rizal, among other works.

February 2020

On February 11, the Philippines notified the United States Embassy in Manila on their decision to terminate the Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) and that the agreement would end in 180 days, provided the decision was not reversed following bilateral negotiations that were scheduled for March 2020. The termination does not spell the end of military relations between the long-term allies, with the long-standing (August 1951) Mutual Defense Treaty (MDT) and more recent (April 2014) Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) both still in place. The VFA, which came into effect May 1999, allowed military personnel from either country visa or judicial privileges, amongst other benefits, as well the United States the right to operate vessels and aircraft in the Philippines freely.

February 2020

Angat Hydropower Corporation awarded GE Renewable Energy a contract for the rehabilitation of 218MW Angat hydropower plant in the Philippines. The facility, located on Angat River, was commissioned in 1967. Under the deal, GE Renewable Energy would supply two new 50MW Francis turbines, four new 50MW generators as well as three new upgraded auxiliary turbines and generators. The firm would also be responsible for assessing the penstock, the powerhouse and providing a new control system. GE Renewable Energy would collaborate with local partner DESCO, which would install and commission the plant. The upgraded plant was due to start operations in 2023 with an increased output of 226.6MW.

April 2020

Work on the new passenger terminal building of Clark International Airport was progressing as scheduled despite the enhanced community quarantine in Luzon, Philippines. Contractor Megawide GMR Construction Joint Venture (MGCJV) stated that work was now 96% complete with only minor works remaining. The new terminal was expected to increase airport's annual passenger handling capacity from 4.2 million to 12.2 million. MGCJV won the construction package in December 2017 by submitting a bid of PHP9.36 billion (USD185.37 million) under a hybrid public-private partnership scheme. The new terminal was expected to be delivered before July 31 2020.

April 2020

The government announced a PHP27.1 billion fiscal package (about 0.15% of 2019 GDP) in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, which comprised, among other areas, support to the tourism and agriculture sectors. Financial assistance would also be provided to affected SMEs and vulnerable households through specialised microfinancing loans and loan restructuring.

Sources: BBC Country Profile – Timeline, Fitch Solutions

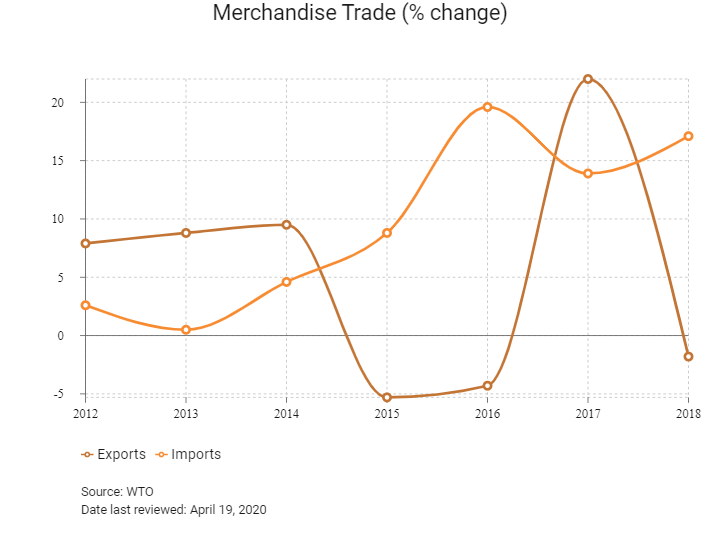

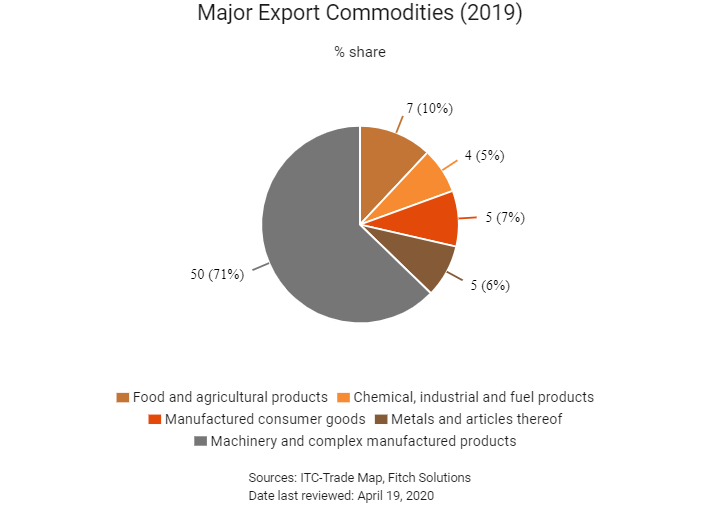

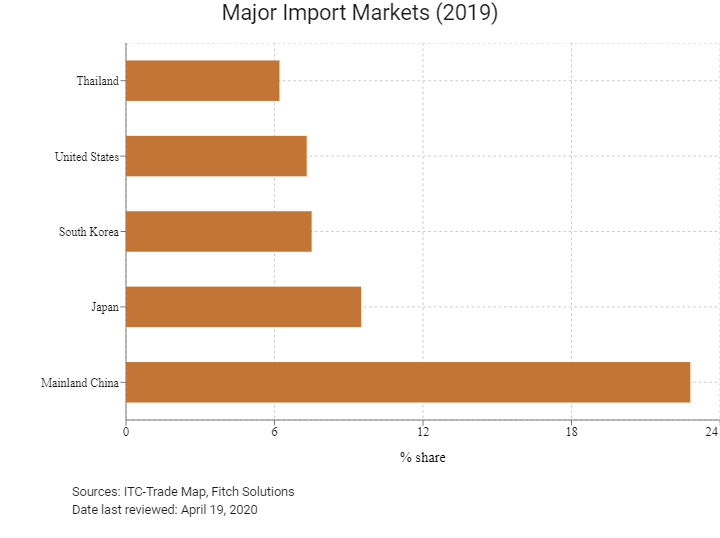

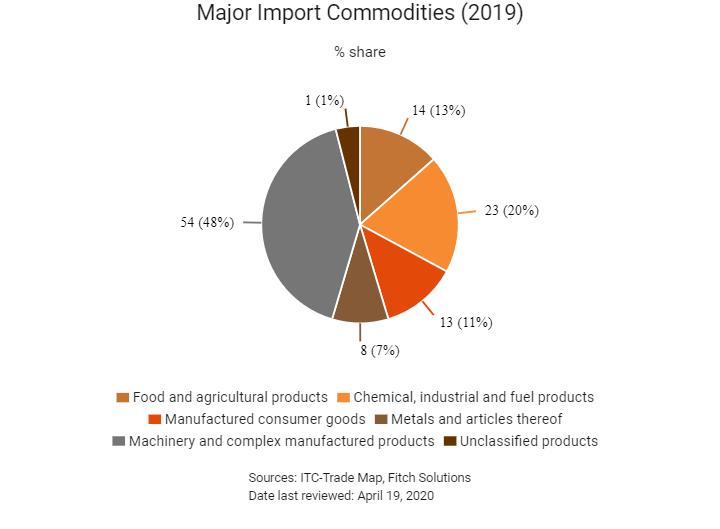

Merchandise Trade

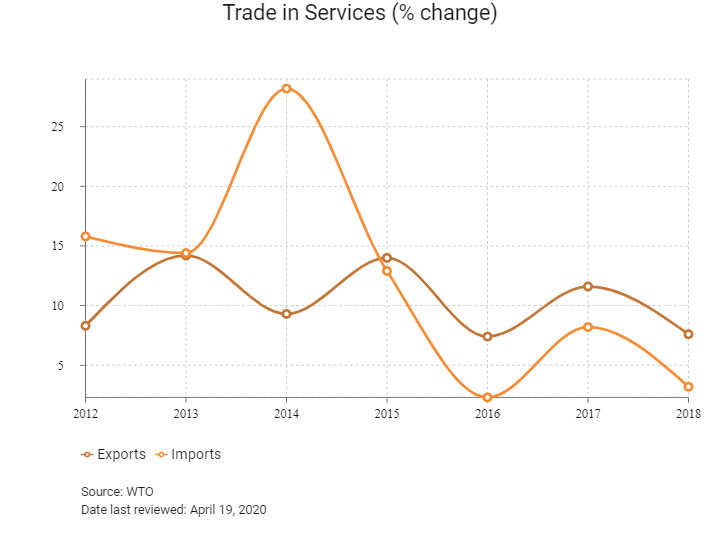

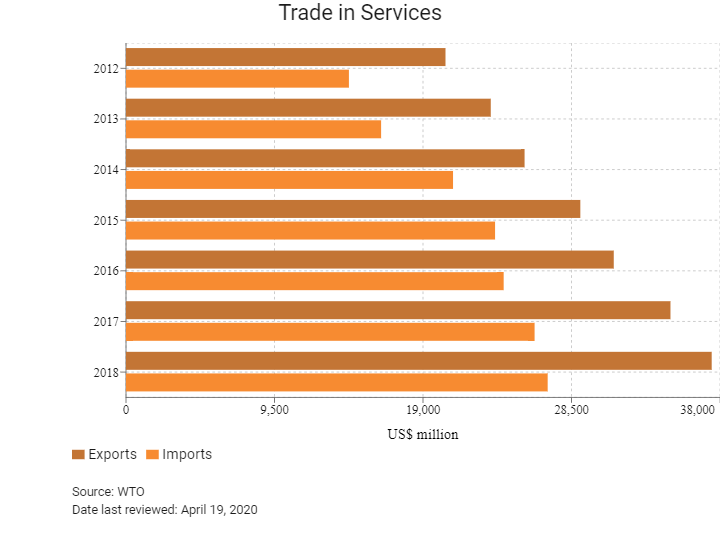

Trade in Services

- The Philippines has been a member of World Trade Organization (WTO) since January 1, 1995.

- The Department of Trade and Industry remains responsible for the implementation and coordination of trade and investment policies as well as for promoting and facilitating trade and investment.

- The Philippines grants most favoured nation (MFN) treatment to all WTO members. The Philippines' simple average MFN tariff was 7.1% in 2016 and 6% of its applied tariffs is 20% or higher. All agricultural tariffs and about 60% of non-agricultural tariff lines are bound under the Philippines' WTO commitments. The simple average bound tariff in the Philippines is 23.5%.

- Imported manufactured goods competing with locally produced goods face higher tariffs than those without local competition. The Philippine government cites domestic and global economic developments to justify the modification of applied rates of duty for certain products to protect local producers in the agriculture and manufacturing sectors.

- The Philippines eliminated tariffs on approximately 99% of all goods from the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) trading partners as a commitment under the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) agreement. The Philippines has been a member of ASEAN since 1967.

- Food products and agricultural inputs are exempt from value-added tax (VAT) which is typically 12%. Excise taxes are levied on alcoholic beverages, tobacco products, automobiles, petroleum products, minerals, perfumes and jewellery.

- A vast range of goods are subject to licences or permits when imported. For certain products, multiple permits or licences are required and informal payments have been reported by the business community.

- About 80% of standards are aligned to international norms. There are 72 mandatory technical regulations covering a wide range of goods. The Philippines Accreditation Bureau has accredited 243 conformity assessment bodies. The Philippines has reformed its food safety regime based on a 'farm-to-fork' approach to enhance food safety. A new Food Safety Act was promulgated in 2013 and its implementing legislation entered into force in 2015. However, the Philippines' sanitary and phytosanitary measure (SPS)-related import requirements for food, which appear to be complex, remain largely unchanged. During the period of 2013 to 2015, the Philippines submitted 46 technical barriers to trade (TBT) notifications and over 200 SPS notifications. Members have not raised any specific trade concerns regarding its SPS and TBT measures.

- Philippine marking and labelling requirements are specified in the Consumer Act of the Philippines (Republic Act No. 7394) and Philippine National Standards (PNS). The Department of Trade and Industry's Bureau of Philippine Standards (BPS) is the national standards body that develops and implements the PNS. All consumer products sold domestically, whether manufactured locally or imported, must contain the following information on their labels:

- Correct and registered trade name or brand name

- Registered trademark

- Registered business name and address of the manufacturer

- Importer or re-packer of the consumer product in the Philippines

- General make or active ingredients

- Net quality of contents, in terms of weight and country of manufacture (if imported)

- The BPS implements a product certification mark scheme to verify conformity of products to PNS and other international standards. This includes critical products such as electrical equipment and electronics, as well as consumer, chemical and construction and building materials. Products manufactured locally must bear a Philippine Standard mark, while imported products must bear Import Commodity Clearance certification marks duly issued by the BPS.

Sources: WTO – Trade Policy Review, Fitch Solutions

Trade Updates

The government is actively seeking new free trade agreements (FTAs) with key trade partners, such as the European Union (EU), and remains committed to reducing current tariff lines for certain products in order to boost competitiveness and ease the trading process for businesses.

Multinational Trade Agreements

Active

- The Philippines is a member of WTO (effective date: 1995).

- AFTA: Came into effect in January 1993. AFTA reduces tariff and non-tariff barriers between 10 member states – Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, Indonesia and Cambodia.

- ASEAN-Australia-New Zealand FTA (AANZFTA): Signed on February 27, 2009, AANZFTA is ASEAN's first FTA with two developed countries simultaneously and the first ASEAN FTA done in a single undertaking. AANZFTA represents ASEAN's most ambitious FTA to date, covering 18 chapters, including new areas that ASEAN had previously never negotiated on, such as competition policy and intellectual property. The AANZFTA also includes an AANZFTA Economic Cooperation Support Programme, which will provide technical assistance and capacity building to the parties of the agreement with the aim of supporting the implementation of it, as well as to support the overall regional economic integration process. The agreement entered into force for all parties in 2012 and work is currently underway to resolve and implement the built-in agenda as stipulated under the agreement. The agreement aims to eliminate tariffs on 99% of exports to key ASEAN markets by 2020.

- ASEAN-Mainland China: The ASEAN-Mainland China FTA covers goods and services. The FTA for goods came into force on January 1, 2005, and the FTA for services came into force on July 1, 2007. The agreement aims to eliminate tariffs, encourage investment and address the barriers that impede the flow of goods and services. The ASEAN-Mainland China Free Trade Area came into force on January 1, 2010 and was upgraded in 2014. In 2019, the ASEAN was the recipient of 14.4% of Mainland China's exports and the source of 13.6% of imports. Total merchandise trade between the ASEAN and Mainland China hit a record high of USD642 billion in 2019.

- ASEAN-South Korea: The ASEAN-South Korea FTA (AKFTA) came into force in June 2007 and May 2009 for goods and services, respectively. The investment agreement entered into force in June 2009. AKFTA aims to create more liberal, facilitative market access and investment regimes between South Korea and ASEAN. A business council was set up in December 2014 to enhance economic cooperation between parties and boost total trade to USD200 billion by 2020. ASEAN was the recipient of 17.5% of South Korea's exports in 2019 and the source for 11.2% of imports. Total trade between the ASEAN and South Korea has more than doubled between 2007 and 2019.

- ASEAN-Japan FTA: Japan provides a huge market for a wide range of goods, with tariff-free trade. This benefits a number of important sectors, including manufacturing, agriculture, mining and chemicals production. Philippines only bilateral free trade agreement is also with Japan, called the Philippines – Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (PJEPA), which covers trade in goods and services, investments, movement of natural persons, intellectual property, custom procedures, improvement of the business environment and government procurement. PJEPA was implemented in December 2008 and provides duty free access to 80% of Philippine exports to Japan, consisting of 7,476 products such as food products, garments and textiles, furniture, metal manufactures, minerals, machinery and equipment parts, electronics, motor vehicle parts and chemicals.

- ASEAN-India FTA: The ASEAN-India Trade in Goods Agreement was signed at the seventh ASEAN Economic Ministers-India Consultations on August 13, 2009. The Agreement entered into force on January 1, 2010 for India and some ASEAN member states. The ASEAN-India Trade in Services and Investment Agreements were signed in November 2014. The Philippines benefits from trade preference in terms of tariff exemption or reduction under the AIFTA, which is a trade bloc agreement between India and ASEAN. This will help member states in terms of trade growth and diversification given the size and performance of the Indian economy and other ASEAN member states.

- ASEAN-Hong Kong FTA (AHKFTA): Hong Kong and ASEAN commenced negotiations of an FTA and an Investment Agreement in July 2014. After 10 rounds of negotiations, Hong Kong and ASEAN announced the conclusion of the negotiations in September 2017 and forged the agreements on November 12, 2017. The agreements are comprehensive in scope, encompassing trade in goods, trade in services, investment, economic and technical co-operation, dispute settlement mechanism and other related areas. The agreements will bring legal certainty, better market access and fair and equitable treatment in trade and investment, thus creating new business opportunities and further enhancing trade and investment flows between Hong Kong and ASEAN. The agreements will also extend Hong Kong's FTA and Investment Agreement network to cover all major economies in South East Asia. The agreement came into force on January 1, 2019, but will take time for all members of ASEAN to comply as implementation is subject to completion of the necessary procedures. Hong Kong is a key export market and the reduction of tariffs will ease the trading process. Hong Kong's potential as a key export market increases the importance of AHKFTA.

- Philippines-European Free Trade Association (EFTA) FTA: The FTA covers trade in goods, services, investment, competition, the protection of intellectual property rights, government procurement and trade and sustainable development with EFTA states (Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland). All customs duties on industrial products are abolished and the Philippines will gradually lower or abolish duties on the vast majority of such products.

Under Negotiation

- Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP): A regional economic agreement that involves the 10-member ASEAN bloc and their FTA partners: Australia, Mainland China, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea. Negotiations on a framework agreement for the RCEP have stalled after India announced its withdrawal from the trade pact at a RCEP summit held in Bangkok in November 2019. Expectations had been for negotiations to conclude in 2019, paving the way for the agreement to enter force by late 2020. RCEP negotiations without India may now be concluded in 2020, but the withdrawal of India represents a setback to attempts to counter the growing wave of protectionism in the US and other parts of the world. The RCEP is envisioned to be a modern, comprehensive, high-quality and mutually beneficial economic partnership agreement that aims to advance economic cooperation, and broaden and deepen integration in the region. The RCEP will lower tariffs and other barriers to the trade of goods among the 15 countries that are in the agreement, or have existing trade deals with ASEAN.

- Philippines-EU FTA: Negotiations are underway to further increase trade flows between the EU and the Philippines under an FTA. The issues of high tariffs for EU automotive exports remain high on the agenda.

- Philippines-South Korea FTA: Negotiations are underway to strengthen bilateral trade between the two states under an FTA. Semiconductors are the most traded product between the two countries, with South Korea also shipping auto parts, pharmaceutical goods and petrochemical products to the Philippines. The Philippines exports agricultural products and garments to South Korea. Negotiations which commenced in June 2019 are anticipated to be concluded in H120.

Sources: WTO Regional Trade Agreements database, Fitch Solutions

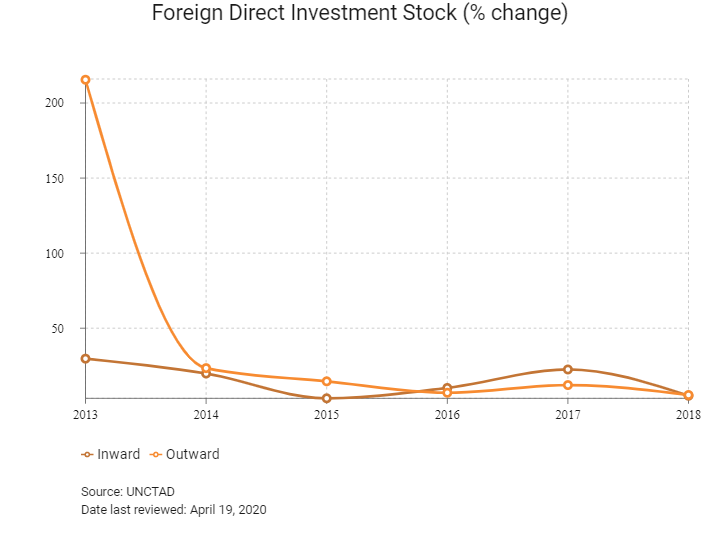

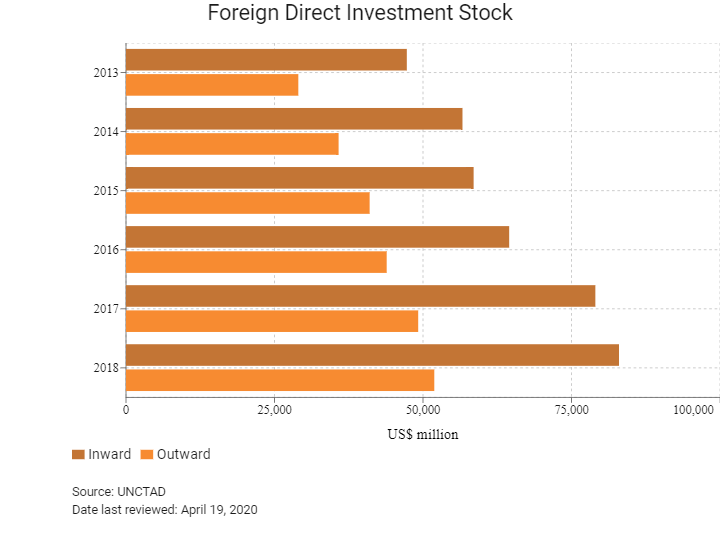

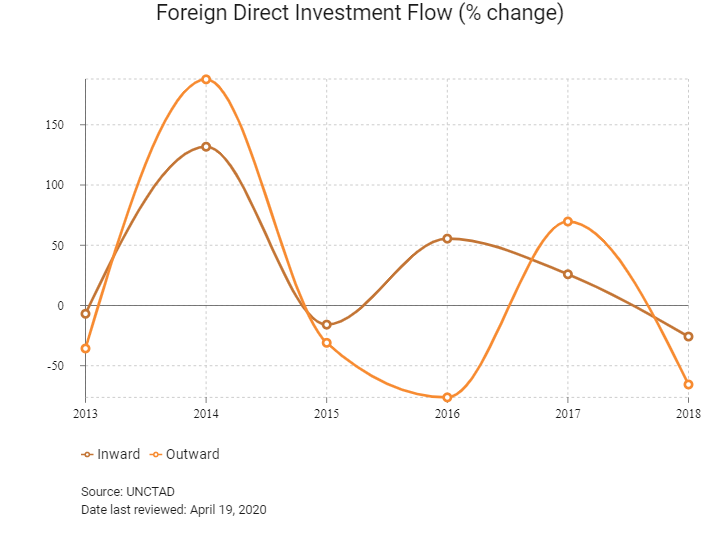

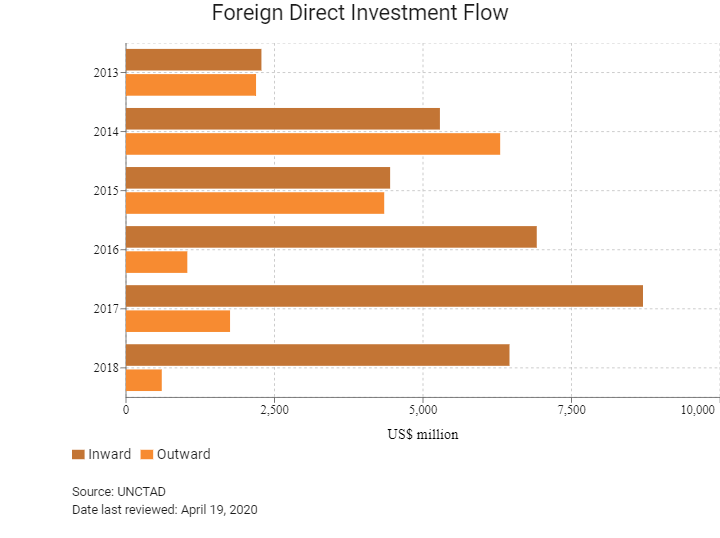

Foreign Direct Investment

Foreign Direct Investment Policy

- The Philippines Board of Investment (BOI) remains responsible for implementation and coordination of investment policies.

- Foreign enterprises are treated equally under law with their domestic counterparts.

- The Philippines is fast becoming a fintech, blockchain and cryptocurrency hub. This is largely due to the relatively accommodating stance which Philippine financial authorities have taken toward cryptocurrency and blockchain adoption.

- Corporations wishing to invest in the Philippines must register with the Securities and Exchange Commission, while individually-owned enterprises must register with the Bureau of Trade Regulation and Consumer Protection in the Department of Trade and Industry. Investors must also register with the relevant agency in order to qualify for incentives.

- An enterprise registered with the BOI – pursuant to the 1987 Omnibus Investments Code – is entitled to a range of incentives, provided they meet the requirements listed. Projects that may be eligible for incentives under the BOI include investments in manufacturing of goods not yet produced in the Philippines, manufacturing that uses new methods or designs, agriculture, forestry, mining, services, nonconventional fuels, enterprises exporting at least 70% of output and projects in less developed areas. The same incentives are also available to businesses that set up operations in one of the numerous special economic zones which operate outside of the Philippines customs area and offer substantial fiscal and non-fiscal advantages to businesses.

- The government has a mandated 'negative list' of sectors (the Foreign Investment Negative List) in which foreign participation is capped at a certain level. The list consists of two parts. Part A lists sectors in which foreign ownership is restricted (such as mass media and private security) and Part B lists sectors in which foreign ownership is limited (such as educational institutions and advertising) for reasons such as national security and public health. The government publishes regular updates to the negative list where restrictions have gradually been reduced on a number of sectors. For example, as of 2014, the government has allowed 100% foreign equity in local subsidiaries of banks. Furthermore, a law signed in 2014 allows foreign banks to enter the Philippine market, where they can establish branches, but cannot open more than six branch offices each.

- Foreigners are banned from fully owning land, although foreign investors can lease a contiguous parcel of up to 1,000 hectares for 50 years, renewable one time for an additional 25 years.

- Philippine law allows expropriation of private property for public use or in the interest of national welfare or defence and offers fair market value compensation. In the case of expropriation, foreign investors have the right to receive compensation in the currency in which the investment was originally made and to remit it at the equivalent exchange rate.

- According to the World Bank Doing Business 2020, the Philippines strengthened minority investor protections by requiring greater disclosure of transactions with interested parties and enhancing director liability for transactions with interested parties.

Sources: WTO – Trade Policy Review, National Sources, US Department of Commerce, Fitch Solutions

Free Trade Zones and Investment Incentives

|

Free Trade Zone/Incentive Programme |

Main Incentives Available |

|

Philippines Economic Zones Authority (PEZA) – 300 zones managed privately and by the government, mainly in the manufacturing, IT, tourism, medical tourism, logistics/warehousing and agro-industrial sectors. |

- Companies established under PEZA receive the same incentives as listed below as well as a 5% tax rate on gross income following the expiration of the income tax holiday. |

|

Philippines BOI Incentives |

- Income tax holidays of four-to-six years. |

Sources: US Department of Commerce, Fitch Solutions

- Value Added Tax: 12%

- Corporate Income Tax: 30%

Sources: Philippines Bureau of Internal Revenue, Fitch Solutions

Important Updates to Taxation Information

In September 2019, Philippines reformed the corporate tax system through the CIT and Incentives Rationalization Act, which will reduce CIT from 30% to 20% over a 10-year period as well as introduce specific tax incentives for capital expenditure and labour up-skilling.

Business Taxes

|

Type of Tax |

Tax Rate and Base |

|

CIT |

30% |

|

Capital Gains Tax |

- 6% on disposal of real property |

|

VAT |

12% on sale of goods and services |

|

Social security contributions |

Maximum contribution of PHP1,178.7 per month per employee |

|

Local Government Taxes |

Up to 3% depending on location |

|

Real Property Tax |

1% in a province or 2% if located in a city |

|

Branch Remittance Tax |

15% on after tax profits |

|

Withholding Tax |

- 15% or 30% on dividends paid to foreign non-resident corporations |

Sources: National Sources, Philippines Bureau of Internal Revenue, Fitch Solutions

Date last reviewed: April 19, 2020

Alien Employment Permit (AEP)

The AEP authorises an individual to work in the country and is valid for either one year or for the length of time stipulated in the employee's contract (but no longer than three years). The AEP is only valid for the respective position and applicable company and a new AEP is required when an employee takes on a new position or joins a different company. Intra-corporate transfers do not require a new AEP. The application for an AEP may be made by either the employee or the employer. The AEP is issued by the Department of Labour and Employment.

9(G) Visa

The AEP is required before obtaining the 9(G) Visa. The 9(G) Visa, or the pre-arranged employment visa, allows for the employment of individuals with skills or qualifications which are not available within the Philippines. The Bureau of Immigration issues this visa and candidates must have secured a job with a company based in the country. A holder of a 9(G) Visa may only work for the employer specified by the visa. If the individual changes employers, the 9(G) Visa automatically downgrades to a tourist visa, requiring the individual to reapply for the 9(G) Visa. The visa is valid for an initial period of one, two, or three years, and can be extended up to three years at a time (depending on the duration of the employment contract) and may be renewed multiple times.

9(D) Visa

The 9(D) Visa (also known as the Treaty Trader Visa) only applies to nationals from Japan, Germany and the United States. To qualify, foreign nationals must prove that they or their employers are engaged in substantial trade, involving investment of at least USD120,000 between the Philippines and their country of origin, they intend to leave the Philippines upon the completion or termination of their work contract, they hold the same nationality as their employer or company's major shareholder and they hold a position of a supervisor or executive in the company. The visa is valid for up to two years.

Provisionary Work Permit

The Provisional Work Permit (PWP) may be obtained while the 9(G) or 9(D) visas is being issued. The AEP is needed for a PWP. The permit is valid for six months.

Sources: Government websites, Fitch Solutions

Sovereign Credit Ratings

|

Rating (Outlook) |

Rating Date |

|

|

Moody's |

Baa2 (Stable) |

20/07/2018 |

|

Standard & Poor's |

BBB+ (Stable) |

30/04/2019 |

|

Fitch Ratings |

BBB (Stable) |

07/05/2020 |

Sources: Moody's, Standard & Poor's, Fitch Ratings

Competitiveness and Efficiency Indicators

|

World Ranking |

|||

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

|

Ease of Doing Business Index |

113/190 |

124/190 |

95/190 |

|

Ease of Paying Taxes Index |

105/190 |

94/190 |

95/190 |

|

Logistics Performance Index |

60/160 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Corruption Perception Index |

99/180 |

113/180 |

N/A |

|

IMD World Competitiveness |

50/63 |

46/63 |

N/A |

Sources: World Bank, IMD, Transparency International

Fitch Solutions Risk Indices

|

World Ranking |

|||

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

|

Economic Risk Index Rank |

31/202 |

29/201 |

26/201 |

|

Short-Term Economic Risk Score |

69.6 |

67.7 |

70.4 |

|

Long-Term Economic Risk Score |

72.1 |

72.9 |

73.5 |

|

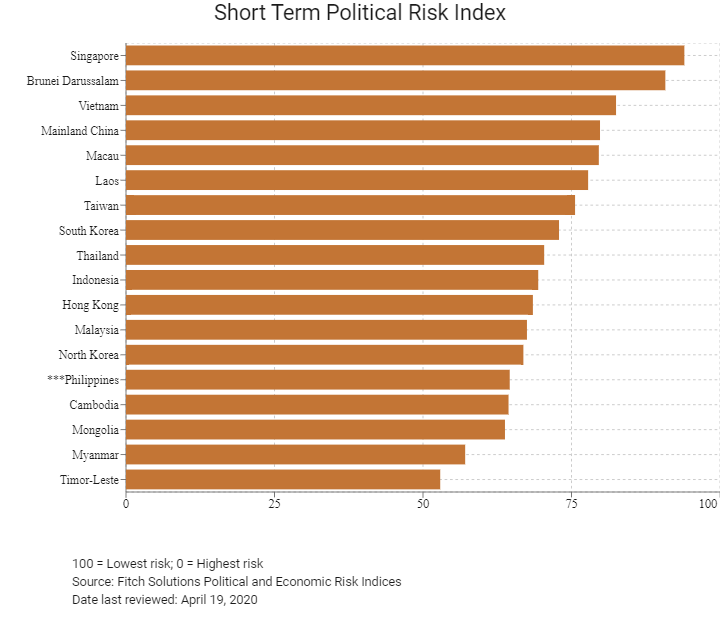

Political Risk Index Rank |

92/202 |

88/201 |

87/201 |

|

Short-Term Political Risk Score |

63.1 |

62.7 |

64.6 |

|

Long-Term Political Risk Score |

64.2 |

64.2 |

64.2 |

|

Operational Risk Index Rank |

124/201 |

112/201 |

110/201 |

|

Operational Risk Score |

43.1 |

47.3 |

47.3 |

Source: Fitch Solutions

Date last reviewed: April 19, 2020

Fitch Solutions Risk Summary

ECONOMIC RISK

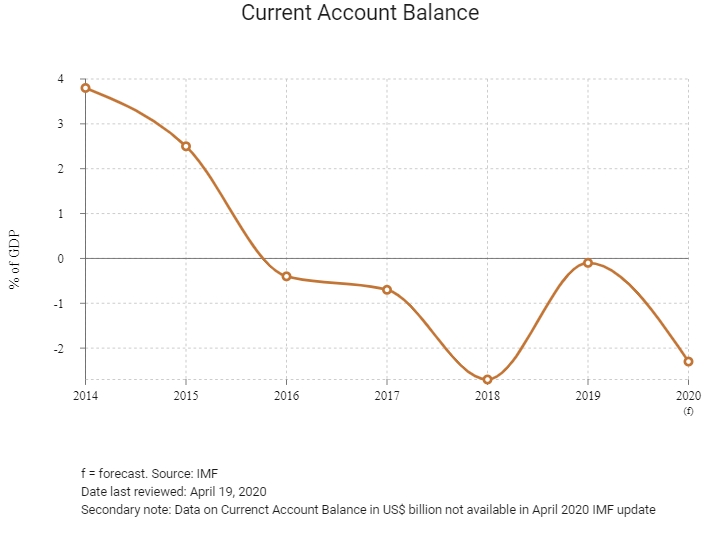

The Philippines’ benefits from continued strong remittances as well as receipts from the business process outsourcing sector, which offset the country’s substantial trade deficit. The country's long-term economic growth prospects have also improved markedly, as the former Aquino administration had sought to address key structural issues and improve the business environment. However, the Covid-19 outbreak poses significant risks to the Philippine economy, particularly if lockdowns are prolonged and extended countrywide.

OPERATIONAL RISK

The Philippines has a large labour market and strong external trade connectivity. However, there are a number of key risks in certain areas, such as internal transport networks and labour costs, which may pose a challenging environment. Philippines' twin deficits leave it somewhat exposed to a sudden bout of risk-off sentiment, with inflation a risk if the peso were to weaken significantly, which in turn could put upwards pressure on import costs for businesses. On a longer term, growing investor sentiment, coupled with an improving business environment on the back of strong reforms, will help propel investment growth in the Philippines.

Source: Fitch Solutions

Date last reviewed: April 20, 2020

Fitch Solutions Political and Economic Risk Indices

Fitch Solutions Operational Risk Index

|

Operational Risk |

Labour Market Risk |

Trade and Investment Risk |

Logistics Risk |

Crime and Security Risk |

|

|

Philippines Score |

47.3 |

57.5 |

49.7 |

45.5 |

36.2 |

|

East and Southeast Asia Average |

55.9 |

56.4 |

57.8 |

55.6 |

53.6 |

|

East and Southeast Asia Position (out of 18) |

13 |

8 |

13 |

12 |

15 |

|

Asia Average |

48.6 |

50.0 |

48.5 |

46.9 |

49.1 |

|

Asia Position (out of 35) |

17 |

8 |

15 |

15 |

28 |

|

Global Average |

49.6 |

50.2 |

49.5 |

49.3 |

49.2 |

|

Global Position (out of 201) |

110 |

53 |

100 |

106 |

144 |

100 = Lowest risk, 0 = Highest risk

Source: Fitch Solutions Operational Risk Index

|

Country/Region |

Operational Risk |

Labour Market Risk |

Trade and Investment Risk |

Logistics Risk |

Crime and Security Risk |

|

Singapore |

83.3 |

77.5 |

90.3 |

79.0 |

86.3 |

|

Hong Kong |

81.5 |

72.0 |

89.0 |

80.7 |

84.5 |

|

Taiwan |

73.0 |

68.3 |

75.3 |

76.3 |

71.9 |

|

South Korea |

70.8 |

62.4 |

70.5 |

79.7 |

70.4 |

|

Malaysia |

69.6 |

62.6 |

74.9 |

74.0 |

66.8 |

|

Macau |

63.9 |

60.9 |

69.5 |

56.2 |

69.1 |

|

Brunei Darussalam |

61.3 |

59.1 |

59.1 |

60.1 |

67.0 |

|

Thailand |

60.7 |

56.6 |

67.7 |

69.2 |

49.4 |

|

Mainland China |

58.8 |

54.9 |

61.4 |

71.8 |

47.3 |

|

Indonesia |

54.4 |

55.1 |

55.1 |

55.7 |

51.8 |

|

Vietnam |

53.4 |

49.3 |

57.5 |

57.8 |

49.0 |

|

Mongolia |

51.1 |

55.3 |

52.5 |

41.0 |

55.6 |

|

Philippines |

47.3 |

57.5 |

49.7 |

45.5 |

36.2 |

|

Cambodia |

40.6 |

44.5 |

43.0 |

35.2 |

39.8 |

|

Laos |

38.4 |

39.5 |

35.5 |

41.0 |

37.6 |

|

Myanmar |

33.1 |

47.8 |

39.1 |

27.8 |

17.8 |

|

North Korea |

32.4 |

51.1 |

18.5 |

27.8 |

32.3 |

|

Timor-Leste |

31.9 |

40.3 |

32.5 |

22.5 |

32.3 |

|

Regional Averages |

55.9 |

56.4 |

57.8 |

55.6 |

53.6 |

|

Emerging Markets Averages |

46.9 |

48.5 |

47.2 |

45.8 |

46.0 |

|

Global Markets Averages |

49.6 |

50.2 |

49.5 |

49.3 |

49.2 |

100 = Lowest risk, 0 = Highest risk

Source: Fitch Solutions Operational Risk Index

Date last reviewed: April 19, 2020

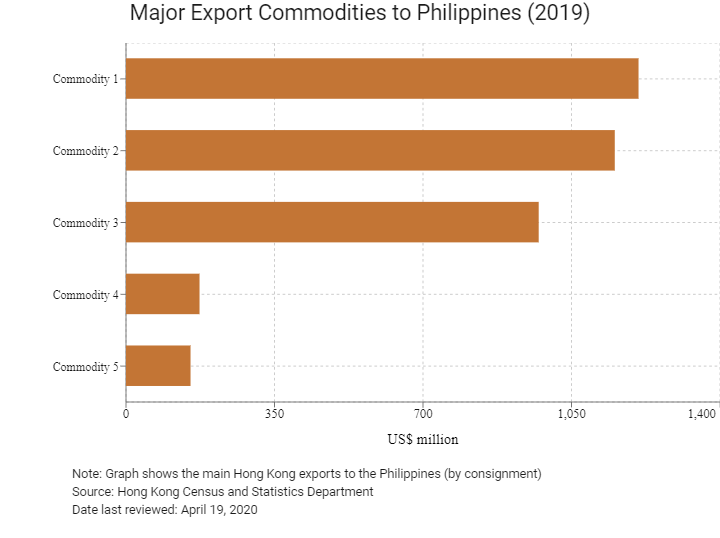

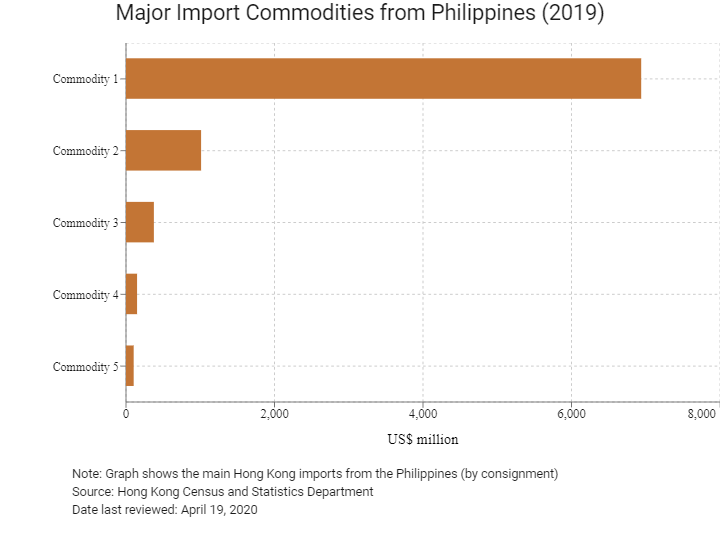

Hong Kong’s Trade with Philippines

| Export Commodity | Commodity Detail | Value (US$ million) |

| Commodity 1 | Office machines and automatic data processing machines | 1,208.0 |

| Commodity 2 | Telecommunications and sound recording and reproducing apparatus and equipment | 1,152.0 |

| Commodity 3 | Electrical machinery, apparatus and appliances, and electrical parts thereof | 972.7 |

| Commodity 4 | Photographic apparatus, equipment and supplies and optical goods; watches and clocks | 173.3 |

| Commodity 5 | Miscellaneous manufactured articles | 152.1 |

| Import Commodity | Commodity Detail | Value (US$ million) |

| Commodity 1 | Electrical machinery, apparatus and appliances, and electrical parts thereof | 6938.7 |

| Commodity 2 | Office machines and automatic data processing machines | 1011.4 |

| Commodity 3 | Telecommunications and sound recording and reproducing apparatus and equipment | 375.4 |

| Commodity 4 | Power generating machinery and equipment | 149.1 |

| Commodity 5 | Vegetables and fruit | 103.4 |

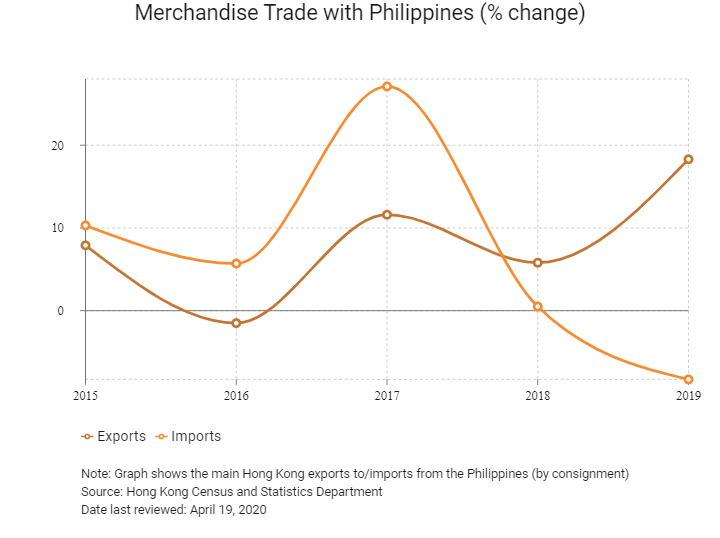

Exchange rate HK$/US$, average

7.75 (2015)

7.76 (2016)

7.79 (2017)

7.83 (2018)

7.77 (2019)

|

2019 |

Growth rate (%) |

|

|

Number of Philippine residents visiting Hong Kong |

875,897 |

-2.11 |

|

Number of Asia Pacific residents visiting Hong Kong |

52,326,248 |

-14.3 |

Source: Hong Kong Tourism Board

|

2019 |

Growth rate (%) |

|

|

Number of Filipinos residing in Hong Kong |

152,771 |

-29.6 |

|

Number of East Asians and South Asians residing in Hong Kong |

2,834,871 |

3.4 |

Note: Growth rate is from 2015 to 2019, no UN data available for intermediate years.

Source: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs – Population Division

Date last reviewed: April 19, 2020

Commercial Presence in Hong Kong

|

2017 |

Growth rate (%) |

|

|

Number of Philippine companies in Hong Kong |

39 |

N/A |

|

- Regional headquarters |

N/A |

|

|

- Regional offices |

||

|

- Local offices |

Source: Hong Kong Census and Statistics Department

Treaties and Agreements between Hong Kong and Philippines

- The Philippines has a Bilateral Investment Treaty with Mainland China that entered into force on September 8, 1995.

- The Philippines has a Double Taxation Agreement with Mainland China that has been applicable since January 1, 2002.

Sources: Fitch Solutions, UNCTAD

Chamber of Commerce or Related Organisations

Philippine Consulate General Hong Kong, China

Address: 14/F, United Centre Building, 95 Queensway, Admiralty, Hong Kong

Email: hongkong.pcg@dfa.gov.ph

Tel: (852) 2823 8501 / 9155 4023

Fax: (852) 2866 9885 / 2866 8559

Source: Hong Kong Protocol Division of Government Secretariat

Visa Requirements for Hong Kong Residents

HKSAR passport holders have been granted visa-free or visa-on-arrival for the Philippines. This visa-free arrangement is valid for 14 days from entering into the country.

Source: Philippine Consulate General Hong Kong, China

Date last reviewed: April 19, 2020

1075 Views

1075 Views Philippines

Philippines