Chinese Mainland

28 Jul 2016

Trends in Global Trade Pacts: “Belt and Road” and “Trans-Pacific Partnership”

By Dr Tse Kwok Leung, Head of Economics & Policy Research, Bank of China (Hong Kong) Limited

To promote its “Belt and Road” strategy, China is currently conducting four major tasks. The first is the planning of infrastructures, and priority projects include the construction of three high-speed rail networks traversing Europe and Asia. These include the Eurasian High-Speed Railway, the Central Asia High-Speed Railway and the Trans-Asian Railway. Commencement of the Eurasian High-Speed Railway is expected to take place this year. The rail link begins in Beijing and enters Russia, heading through Moscow and on towards Warsaw, Berlin and Paris, with London as a possible terminus. The Central Asia High-Speed Railway begins in Urumqi and heads through Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Iran, Turkey and Germany. The Trans-Asian Railway, on the other hand, will span more than 3,000 km. It begins in Kunming and heads to Singapore, going through Southeast Asian countries such as Laos and Malaysia. Based on its current progress, the rail project is expected to be completed by 2020.

The second task involves port infrastructure projects. Gwadar Port in Pakistan is one of the highlights. Gwadar Port is not only a pier where goods both enter and leave, it is also expected to develop into a modern industrial park where an array of high value-added activities will take place. Eventually, it is expected to grow into a logistics hub.

The third task is to establish overseas trade and economic cooperation zones. According to the Ministry of Commerce, China has established 118 trade and economic cooperation zones in 50 countries across the globe. Of these, 77 are located in 23 countries along the route of the “Belt and Road” initiative. At present, most companies operating in these zones are privately-owned enterprises of Mainland China. Hong Kong companies are also welcome to take up tenancy in these zones. They are important fulcrums of the “Belt and Road” initiative.

The fourth task is to set up or take part in multilateral financial institutes, including the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the BRICS New Development Bank, the Silk Road Fund and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. The AIIB officially commenced operation on 16 January 2016. Headquartered in Beijing, the AIIB has 57 Prospective Founding Members, and an initial registered capital of USD 100 billion.

This article is reproduced with the permission of ECIC. Please click here for the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

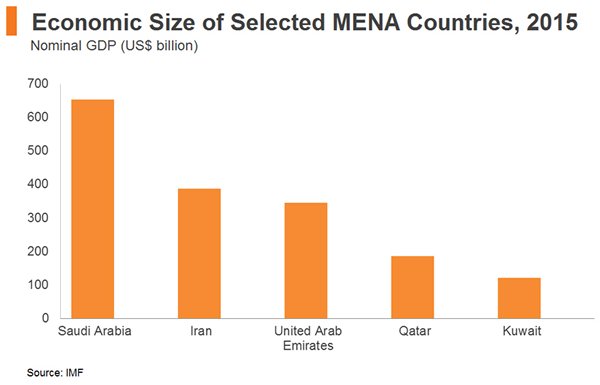

Iran Unbound: A Land of Business Opportunity

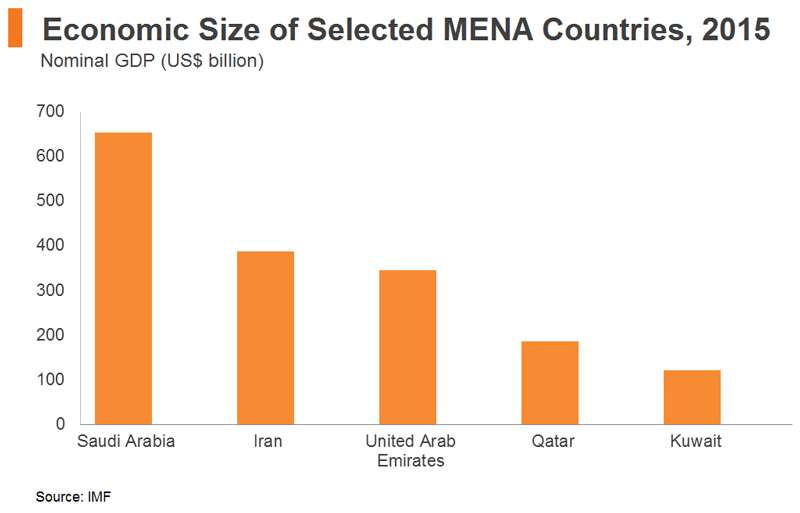

After Saudi Arabia, Iran is the second-largest economy in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, with an estimated nominal GDP of US$387.6 billion in 2015. Following the removal of major international sanctions in January 2016, Iran has been the subject of considerable interest from foreign investors seeking business opportunities in this upper-middle-income[1] country. Overall, the country is characterised by a young and well-educated population, the majority of whom were born after the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran in 1979.

In light of the above, HKTDC Research recently undertook a field trip to Iran, setting out to assess the suitability of the country as an export destination for Hong Kong consumer products, such as electronics, garments and household goods, and to explore opportunities in Iran’s services market for Hong Kong services providers (HKSS) in a number of areas, including construction, project management, logistics, design and finance.

While the gradual restoration of access to the global financial and trading system is expected to enhance the investment climate in Iran, following the removal of nuclear-related UN or “secondary” sanctions in January 2016, HKTDC Research took into account lingering concerns over the so-called “primary” sanctions, which relate to trade with US individuals or companies. In addition, we also undertook a review of the country’s macroeconomic environment and local business practices in order to present an informed understanding of the local market conditions.

This report includes an overview of the business opportunities on offer, with the possible downside pertaining to any early market entry to Iran discussed in another article - Iran Unbound: Balancing Opportunities with Practical Business Risks.

The JCPOA Agreement: a Game Changer

From the time Iranian President Hassan Rouhani took office in August 2013, the government has made great strides towards reducing tensions between Iran and the West. Such tensions had led to a series of US, UN and EU sanctions, including a trade embargo, the freezing of overseas Iranian assets, and the prohibition of financial and bank dealings with Iran.

After some two years of negotiations, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), a historical agreement between Iran and the P5+1 (the UN Security Council’s five permanent members plus Germany), was concluded in July 2015.

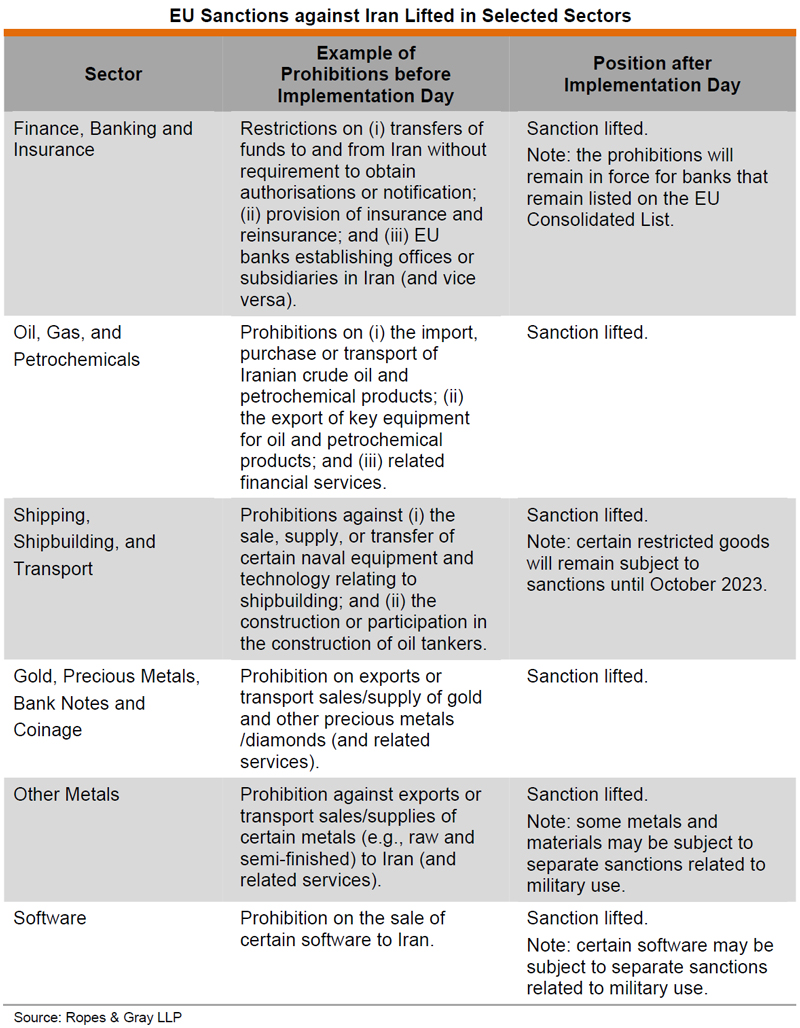

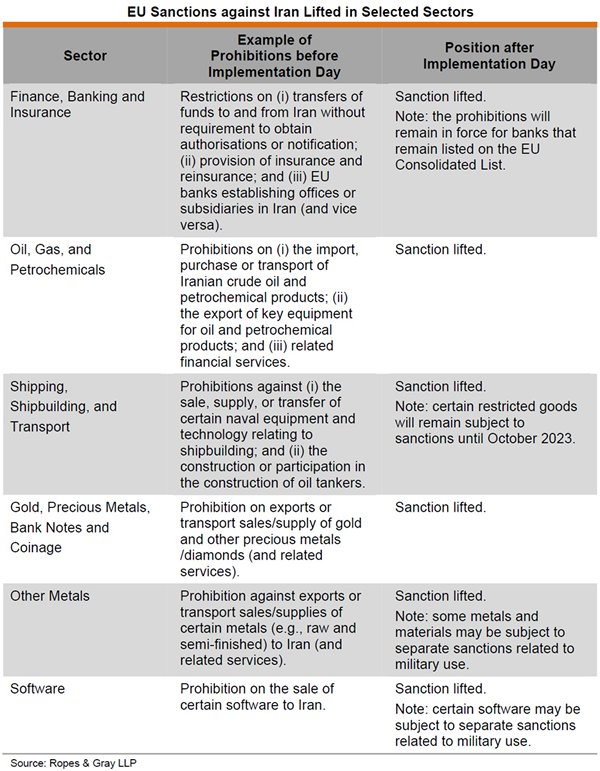

Under the terms of the JCPOA, major economic sanctions against Iran have been removed in exchange for Iran accepting international scrutiny of its nuclear programme. The JCPOA was implemented on 16 January 2016 (“Implementation Day”), heralding the removal of secondary sanctions, including the bulk of EU sanctions against Iran, along with the release of frozen overseas Iranian assets. While the US’s primary sanctions against Iran remain in place, the deal paves the way for a number of companies – primarily European - to re-enter Iran and invest in many of the country’s major economic sectors, such as transport, oil and gas, banking and finance.

In addition, an estimated US$100 billion in frozen assets, relating mostly to oil sales to Asian countries and held in escrow accounts during the sanction period, has been gradually released to Iran, providing the necessary capital for the country to fund its domestic development. Iran has been able to conclude many large procurement deals in the months following Implementation Day.

SWIFT Reconnection Lowers Transaction Costs

Iran’s international banking activity has severely curtailed since 2012, when almost all of the country’s banks were prohibited from using the Society for the Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications (SWIFT) system, a global financial transaction protocol.

Following the implementation of the JCPOA, Iran access to the SWIFT system was restored in February 2016, allowing many Iranian banks to resume cross-border transactions. This has inevitably lowered transaction costs for Iranian companies in light of the intermediary costs that would otherwise be paid to Dubai middle-men. It also eases the country’s general trading environment.

So far, some 30 Iranian banks, including Bank Melli and Bank Mellat, have re-joined SWIFT. As a sign of the further normalisation of banking ties, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) has applied to open branches in Iran. Italy’s Monte Paschi Di Siena Bank is also reported to have provided bank guarantees and letters of credit services to several Iranian banks following the lifting of sanctions. Nonetheless, many major international banks have been hesitant about resuming business ties with Iran, particularly in view of the outstanding primary sanctions.

Restored Macroeconomic Stability Helps Economic Prospects

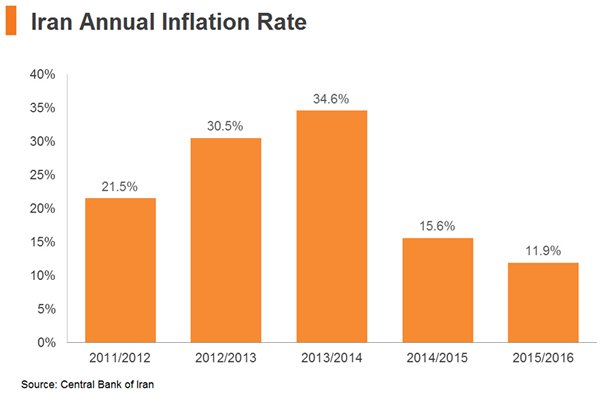

In light of the impact of international sanctions on Iran’s economy – including heavy borrowing from the Central Bank of Iran (CBI) to fund widening government deficits – the Rouhani government, which took power in 2013, has taken major measures aimed at tackling soaring inflation and unemployment.

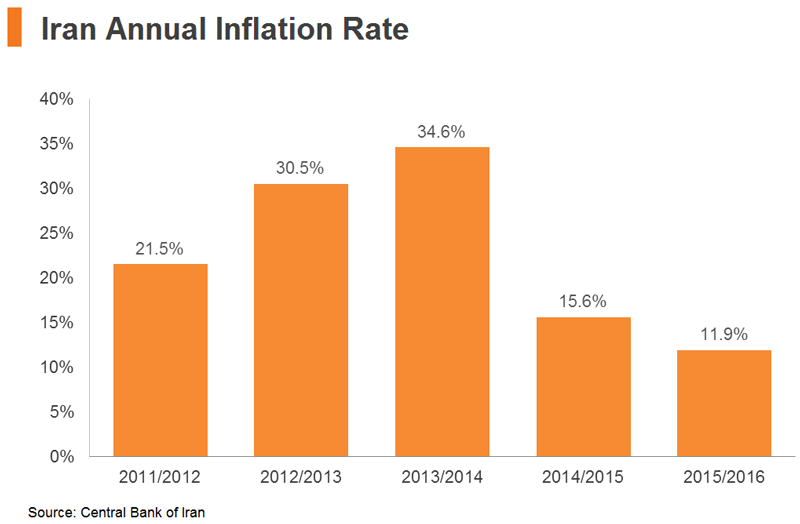

In 2013, following the expansion of sanctions imposed by the US and the EU against the country’s energy and banking sectors, the country’s level of inflation hit a peak of 40%. In order to stabilise this, the Rouhani government introduced a number of measures, including major subsidy reforms and the replacement of cash hand-outs with non-cash benefits. As a result, consumer price inflation over the past Iranian calendar year[2] eased to 11.9% from 15.6% year-on-year. According to the CBI, this declining trend is anticipated to continue, with inflation expected to edge down to single digits by March 2017.

In order to tackle the country’s high unemployment rate, which stood at 11.8% in the first quarter of 2016, the Rouhani administration has proposed ambitious economic reforms through a process of privatisation.

Iran has a large public sector. This exerts substantial control over the economy through state-owned enterprises (SOEs) or semi-private entities, such as foundations, pension funds and companies linked to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). In 2016, it was announced that Iran Air, the government-owned Iranian flag carrier, and the country’s car industry, were to be privatised, along with 201 companies on the 2016 Divesting Lists published by the Iranian Privatisation Organisation. It is believed that this will help improve efficiency by releasing resources tied up in inactive projects and used to fund budgetary shortfalls, ultimately giving an extra push to the privatisation agenda.

Post-Sanctions Development Calls For Foreign Investment

Following years of limited access to external capital, the Iranian government is now keen to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) across a number of sectors, particularly those where new equipment and technology are in high demand.

In the short-to-medium term, the focus of the Iranian economy is expected to be on bridging the funding gap related to major investment projects. In particular, the Iranian government aims to attract up to US$50 billion annually in order to meet an ambitious 8% GDP growth target, as set out in in the sixth Five-year Development Plan for the 2016-2021 period.

Over the longer term, it is estimated that Iran will create investment opportunities of US$1.5 trillion between 2016 and 2025 for local and international investors.

In line with Vision 2025, the Iranian government identifies a number of core industries that the country will focus on developing. These include petrochemical products, metals and minerals, energy, food, pharmaceuticals, industrial machinery and equipment, home appliances, textiles and apparel, and transport.

More specifically, several strategic growth objectives have been outlined in relation to this long-term development plan. These include productivity enhancement through the adoption of advanced technologies; a focus on innovation-driven manufacturing; economic diversification from oil and gas to high value-adding downstream segments; and the establishment of joint-venture manufacturing plants to lower export costs.

It has also been reported that the Iranian government plans to incrementally increase its net investment in manufacturing. This emphasis on manufacturing growth presents ample opportunities for foreign companies to participate in Iran’s ongoing transformation, whether through investing in the manufacturing of petrochemical products, steel, automobiles and consumer goods, or by providing services related to technology, manufacturing process enhancement and the financial sectors.

Opportunities Not Confined to Capital-Intensive Sectors

Home to the world’s second- and fourth-largest reserves of natural gas and crude oil respectively, Iran’s economy is more diversified than most other oil-rich countries in the region, with oil export revenues accounting for only about 30% of the government budget. In the 2014/15 fiscal year, which ended 20 March 2015, the oil sector contributed 15.3% of Iran’s gross national product, followed by the restaurant and hotel trade (15.0%), real estate, specialised and professional services (15.0%), manufacturing (11.8%) and agriculture (9.3%).

Although the oil and gas and other large-scale, capital-intensive sectors such as transport and infrastructure are expected to be the most immediate beneficiaries following the lifting of sanctions, the country is also fast attracting the attention of companies across a number of non-oil industries.

It is worth noting that Iran has maintained a reasonably large domestic manufacturing industry despite the many years of sanctions. This means Iran is quite different to many other emerging markets, where the installation of entirely new production plants is often required, entailing large sums of initial capital. FDI investors in Iran instead have the option of upgrading existing facilities, thus diminishing initial capital requirements. Furthermore, the government is committed to providing a host of incentives to FDI investors, many of which are sector-specific.

Consumer Goods Opportunities

With a population of nearly 80 million and more than 60% of its citizens aged 30 or under, Iran is also one of the largest retail markets in MENA with strong growth potential for imported goods. Throughout the sanctions period, Iran’s large middle class maintained a strong preference for foreign products, with this strong demand met by imports through Dubai and Turkey. This preference is expected to further strengthen in the post-UN sanctions era, as trade and banking normalisation eases related business activity.

During its recent field trip to Iran, HKTDC Research was informed that western companies – including several soft drinks companies – had already entered into domestic licensing deals, under which their products could be manufactured within Iran. At present, Iranian traders and middlemen source products from many international brands via Dubai and Turkey, before re-exporting them to Iran. It was also reported that cargo carriers regularly ship goods to Iran from the free trade zones in Dubai, such as the Jebel Ali Port. Iranian free trade zones, such as Kish Island and Qeshm Island, are locations where international products, many of which are fast-moving consumer goods destined for mass markets, are shipped back to the mainland of Iran.

Prior to the lifting of UN sanctions, most Iranian customers had to make do with “international products” that were of an inferior quality, many of them counterfeit. With sanctions now lifted, Iran’s retail landscape is likely to experience rapid changes in response to the pent-up demand for authentic, high-quality imported goods, including electronics, telecom products and parts, watches and clocks, jewellery, clothing and other consumer products.

As the US has retained its primary sanctions, banning US citizens, companies and financial institutions from doing business with Iran, all transactions made between Iran and the rest of the world are primarily conducted in currencies other than US dollars, notably Euros or RMB. As such, Hong Kong companies which can settle payments in RMB have a distinct advantage.

In addition, as the consumer market further opens up to international companies, there will be an increasing demand for modern retail outlets in order to serve the needs of a young, tech-savvy population, many of whom increasingly prefer large shopping complexes to the traditional bazaars. This may fuel the further development of the construction sector, with new shopping facilities now being built to meet this surging demand.

An Emerging Trade Hub along the Belt and Road

Throughout the sanctions period, China maintained a business relationship with Iran. China has been Iran’s largest trading partner for six consecutive years and there is already a strong foundation in place for both sides to strengthen their economic relationship in the post-sanctions era.

Following the removal of sanctions, China’s President Xi Jinping visited Iran in January 2016. During the visit, the two countries entered into an agreement on a 25-year comprehensive strategic partnership that will deepen co-operation in a number of areas, including communication, railways, ports, energy, trade and services. This will entail a tenfold boost in bilateral trade, taking it to more than US$600 billion over the next decade.

One of the major countries along the China-Central Asia-West Asia (CCAWA) Economic Corridor, as mapped out under China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Iran is expected to benefit from the BRI’s focus on infrastructure development and technology collaboration. This should stimulate demand across a number of sectors, including rail and road transport, energy, telecommunications and real estate.

At the time of writing, the China National Transport Equipment & Engineering Co Ltd is reportedly close to finalising an agreement on a US$3 billion high-speed rail project connecting Tehran with Mashhad. There are also plans for China and Iran to establish a 3,000-4,000 hectares joint industrial estate in Jask Port in southern Iran. This will focus on petrochemical projects, refinery, and steel and aluminum production.

A Potential Gateway to Regional Markets

Located in Southern Asia and bordering the Persian Gulf, the Caspian Sea and the Gulf of Oman, Iran prides itself on being a gateway to a regional market of more than 400 million people, spanning Afghanistan, Iraq, Turkey, Russia and the Central Asia countries. Following the lifting of sanctions, the subsequent easier movement of goods will result in significant trade opportunities, helping Iran to emerge as a trade and logistics hub in the region.

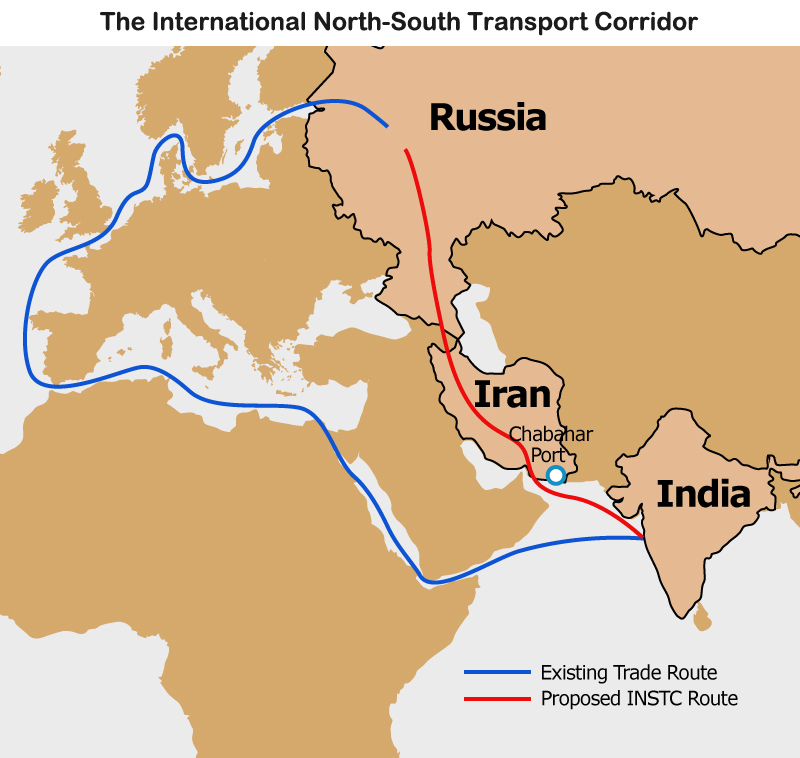

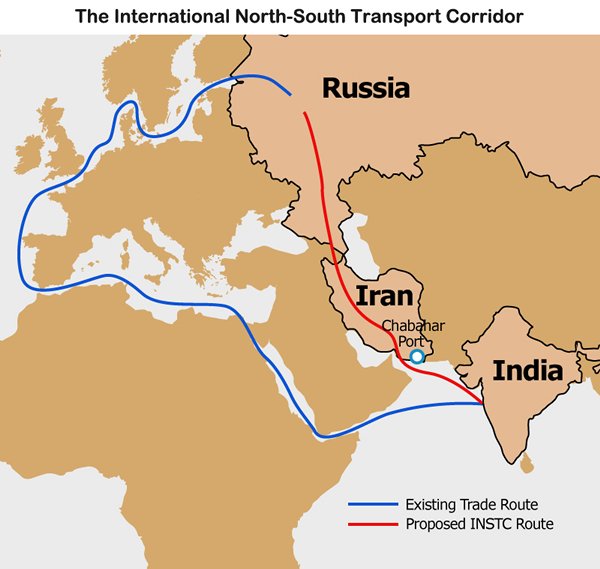

As indicated above, Iran is also a major country along the CCAWA Economic Corridor, an important element in China’s BRI. While the BRI is intended to enhance land and sea connectivity with countries along its key routes, the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), established in 2000, aims to connect the Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf to the Caspian Sea via Iran, and onward to northern Europe via St. Petersburg in Russia. As a multi-modal transport corridor, INSTC will make Iran a key link in connecting the 14 member states, including India and Russia[3].

Moreover, in May 2016 India announced plans to invest US$200 million in developing two terminals and five berths at the Iranian port of Chabahar, with an additional US$300 million available for related infrastructure development. The Iranian government is reportedly now seeking investment from other countries to help fully develop the area.

In addition to construction projects, Asian manufacturers seeking to export to Europe might also benefit from Iran’s geographic proximity to the region, should they choose to establish a production base in the country. Iran boasts dozens of free zones and special economic zones where foreign investors can build new production plants while benefiting from a range of investment incentives.

[1] According to the World Bank, Iran is classified as an upper-middle-income economy, with a GNI per capita between US$4,126 and US$12,735.

[2] The Iranian calendar year of 1394 ended on 19 March 2016.

[3] The member states in the International North-South Transport Corridor include: Iran, India, Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Oman, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Syria, Ukraine, Turkey, Kyrgyzstan and Bulgaria (observer).

| Content provided by |

|

Editor's picks

Trending articles

China's “Going Out” Initiative: Service Demand of Western China to Tap Belt and Road Opportunities

Thanks to the active overseas investment of Chinese enterprises in recent years and the Chinese government’s advancement of the Belt and Road Initiative, China was the world’s third-largest source of foreign investment for the fourth consecutive year in 2015. In fact, many mainland enterprises are stepping up their efforts in “going out” to look for brands, technologies and other resources to boost their competitiveness, while bringing in the advantages of foreign partners as a way to further develop Chinese and overseas markets.

HKTDC Research recently conducted a questionnaire survey with enterprises in western China. The results reveal that in order to deal with such challenges as securing financing, escalating production costs and market slowdowns, mainland enterprises are keen to seek outside professional services to help them achieve transformation and upgrading. These range from brand design and promotion strategies, to marketing and product research and development (R&D), to financial and legal services.

Moreover, the majority of enterprises surveyed said they would consider “going out” further to tap business opportunities in countries along the Belt and Road routes, particularly in ASEAN countries and other Southeast Asian markets. As well as aiming to sell more industrial/light consumer products to Belt and Road markets, they also wish to carry out sourcing and investment activities such as setting up factories.

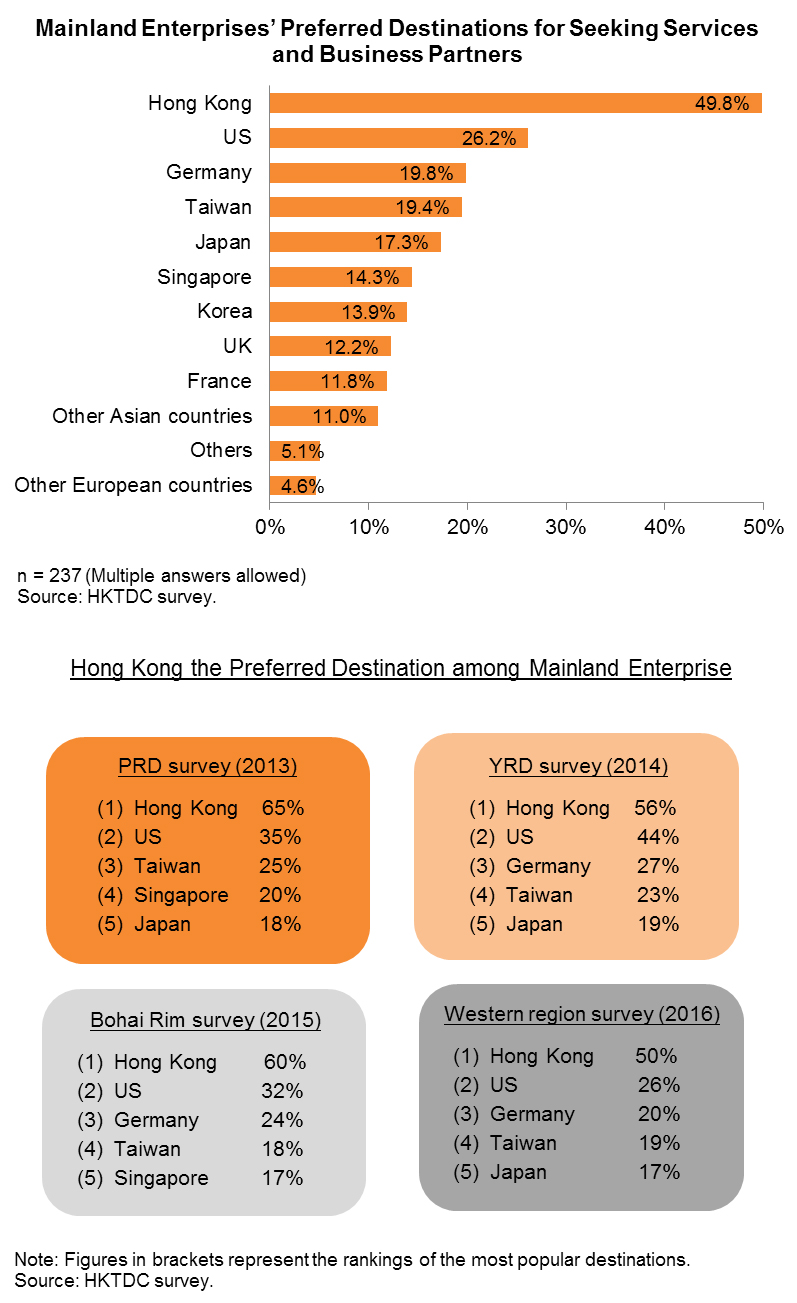

The largest proportion of the surveyed enterprises (50%) said that, in the course of “going out”, they would be most interested in going to Hong Kong to seek professional supporting services and business partners. This is in line with the results of similar surveys carried out by HKTDC Research in the past three years, namely in the Pearl River Delta (PRD) in 2013, the Yangtze River Delta (YRD) in 2014 and the Bohai Rim in 2015. Therefore, whether in the coastal regions or in western China, it is apparent that Hong Kong is the preferred services platform for mainland enterprises intent on “going out”.

New Pattern of Opening Up Under the 13th Five-Year Plan

China is not only a leading destination for foreign direct investment (FDI), but it also ranks among the world’s top sources of FDI. Indeed, China has in recent years significantly relaxed its administrative measures on outbound investment in order to facilitate the “going out” of enterprises to invest overseas. Furthermore, the Belt and Road Initiative strengthens mutually beneficial co-operation with countries along its economic corridors.

Adopted in March 2016, China’s 13th Five-Year Plan[1] stresses the need to establish a new pattern of all-round opening up in the next five years (2016-2020). It encourages enterprises to “go out” to establish sales networks in foreign markets and to bring in the advantages of foreign partners to enhance competitiveness. Meanwhile, bilateral and multilateral co-operation mechanisms will be improved to encourage co-operation and investment in countries along the Belt and Road routes, infrastructure connectivity and trade facilitation advanced, and co-operation in energy and industry chains strengthened. It can therefore be expected that China’s outbound investment activities will see further expansion.

(For further details, please see Opportunities Arising from China’s 13th Five-Year Plan: An Overview.)

The World’s Third-Largest FDI Source

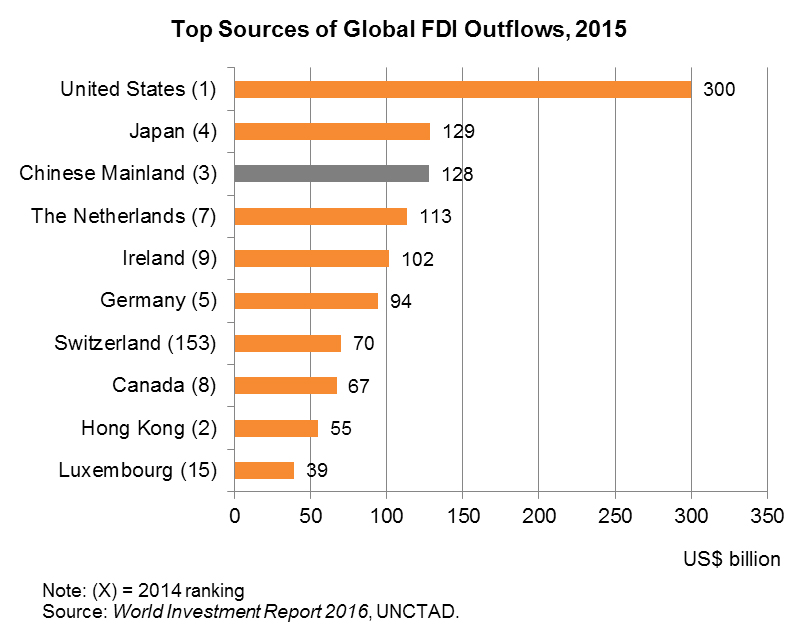

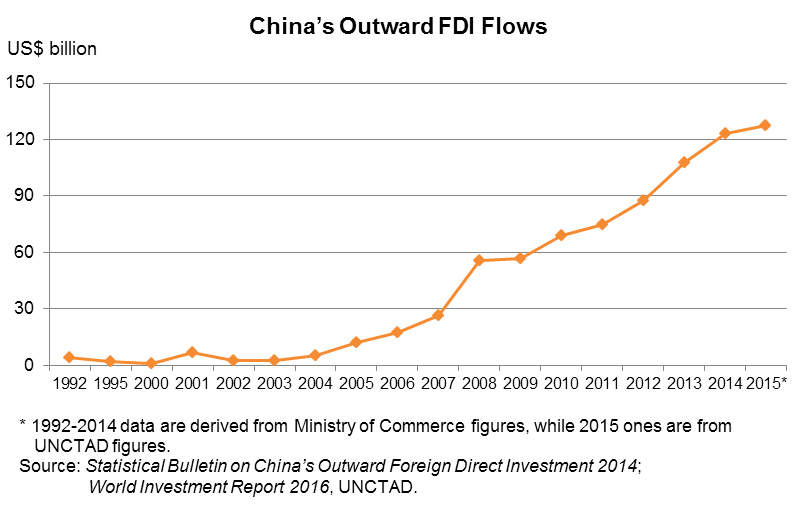

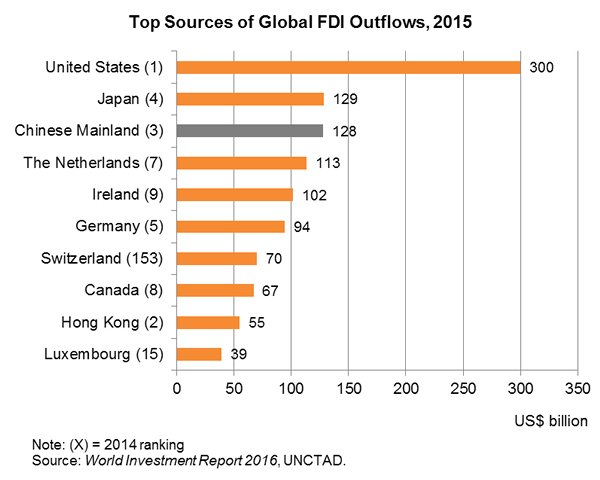

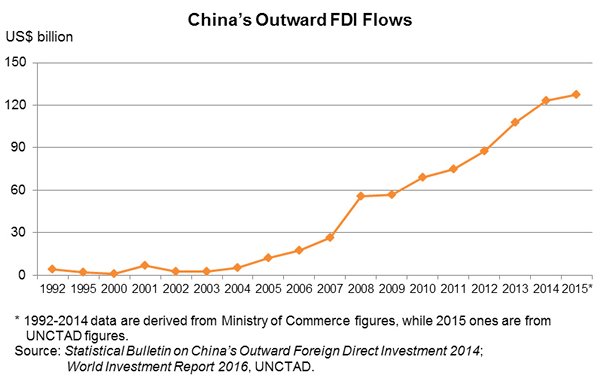

According to the latest United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) figures[2], for four straight years since 2012 China has been the world’s third-largest source of FDI. China’s total outward FDI flows have increased from US$123.1 billion in 2014 to about US$127.6 billion in 2015, trailing only the United States (US$300 billion) and Japan (US$128.7 billion).

Although China has entered into a “new normal” of slower economic growth in the past few years, it has gradually become a main investor in certain developed countries. In particular, investment through cross-border mergers and acquisitions has been increasing, and has moved away from the previous pattern of focusing on energy and natural resources to a diversified pattern covering wholesale and retail, transportation and shipping/warehousing, and real property development. Furthermore, many Chinese enterprises have engaged with their foreign partners in co-operation projects involving technology, or are carrying out various types of commercial co-operation activities with foreign brands, as a way to further develop Chinese and overseas markets.

Meanwhile, China’s direct investment in Belt and Road countries is continually increasing, rising substantially from about US$400 million in 2004 to US$13.66 billion in 2014, an average annual increase of about 43%. Ministry of Commerce figures show that in 2015 Chinese enterprises made non-financial sector direct investment totalling US$14.8 billion (+18.2%) to 49 Belt and Road countries, accounting for 12.6% of China’s total non-financial sector direct investment that year. The investment flows were mainly directed towards Singapore, Kazakhstan, Laos, Indonesia and Russia.

It is worth noting that a considerable number of Chinese enterprises choose Hong Kong as their main channel for carrying out outbound investment – not only because Hong Kong is an international financial centre in the region with such advantages as free flow of capital. Abundant global communications and market network resources, as well as the availability of a complete range of professional services, are also key factors attracting mainland enterprises to use the Hong Kong platform in “going out”.

According to Ministry of Commerce figures, in 2014 the Chinese mainland routed US$70.9 billion in outward FDI through Hong Kong, accounting for 57.6% of the mainland’s total FDI outflows that year. Based on cumulative investment stock as at the end of 2014, the mainland has made US$509.9 billion in outward FDI through Hong Kong, accounting for 57.8% of the mainland’s outward FDI stock.[3]

Hong Kong: a Preferred Platform

Many cities and economic regions along China’s coast have been open to the outside world for many years. As China’s economy and investment outflows expand, coastal regions, provinces and cities, such as the PRD, YRD and Bohai Rim, have become main sources of outbound investment. On the other hand, with the western region including Sichuan province and Chongqing municipal benefiting from the Western Development strategy and other preferential policies, and with the efforts of provinces and cities concerned in attracting outside businesses and capital, the economy in the western region has been developing rapidly. Western China has always been an important gateway, a trading and logistics hub and an industry exchange ground connecting to Central Asia, South Asia and West Asia, and now enterprises in the region are also developing related investment and trading opportunities under the country’s “going out” and Belt and Road initiatives.

In May 2016, HKTDC Research conducted a questionnaire survey at the SmartHK fair held in Chengdu, the capital city of Sichuan province. As well as seeking to understand what challenges enterprises in western China are facing in their operations, the survey also aimed to find out about their intentions concerning transformation and upgrading, in “going out” to tap Belt and Road business opportunities, and their demand for professional services.

The survey followed similar studies carried out by HKTDC Research in the past three years in the PRD (2013), the YRD (2014) and Bohai Rim (2015) regions.[4] In the current survey, 237 effective questionnaires were completed by mainland enterprises (comprising trading companies, manufacturers and service suppliers) mainly from Sichuan, Chongqing and elsewhere in the western region.[5] The opinions of these 237 mainland enterprises on “going out” to tap Belt and Road business opportunities are outlined below.[6]

-

Challenges in Business Operations

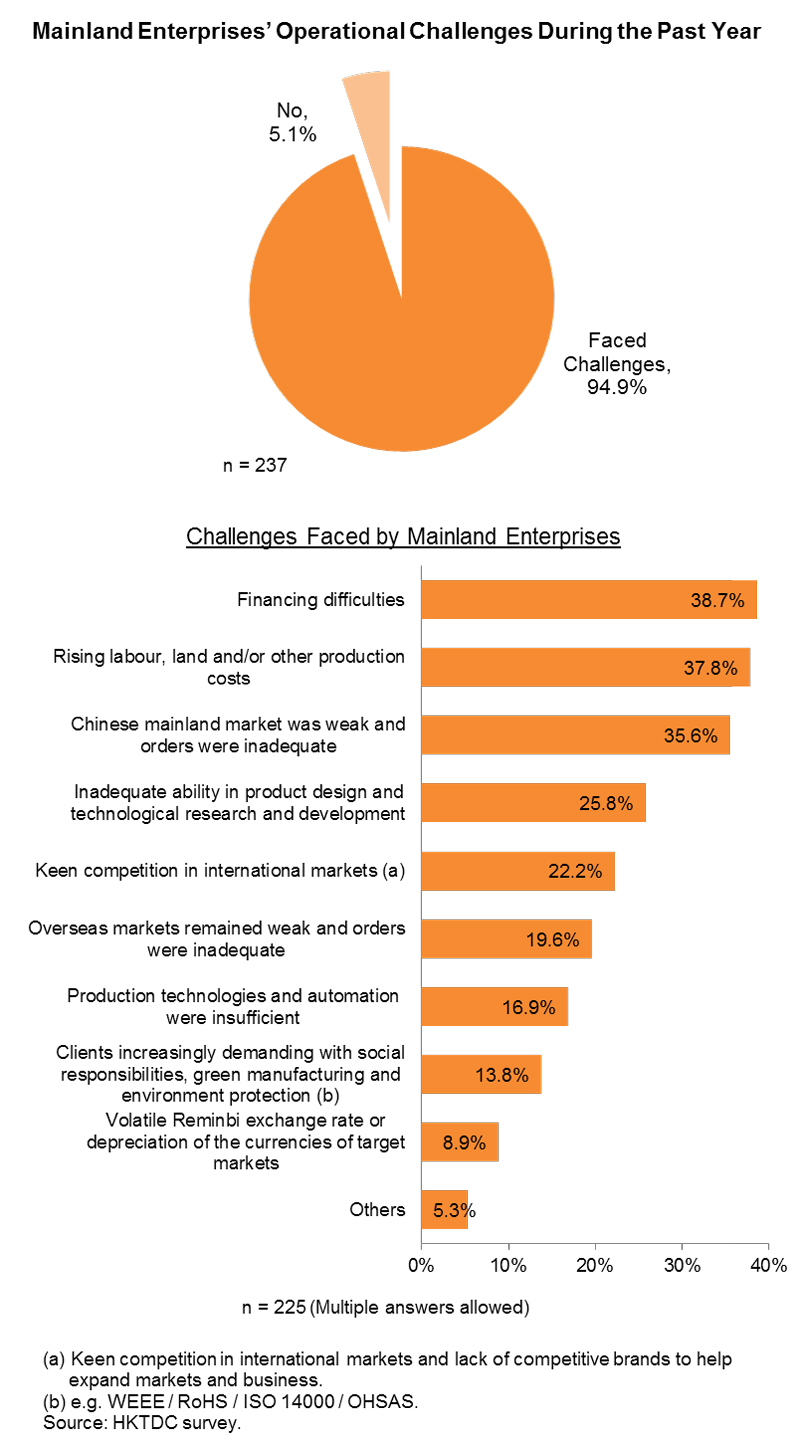

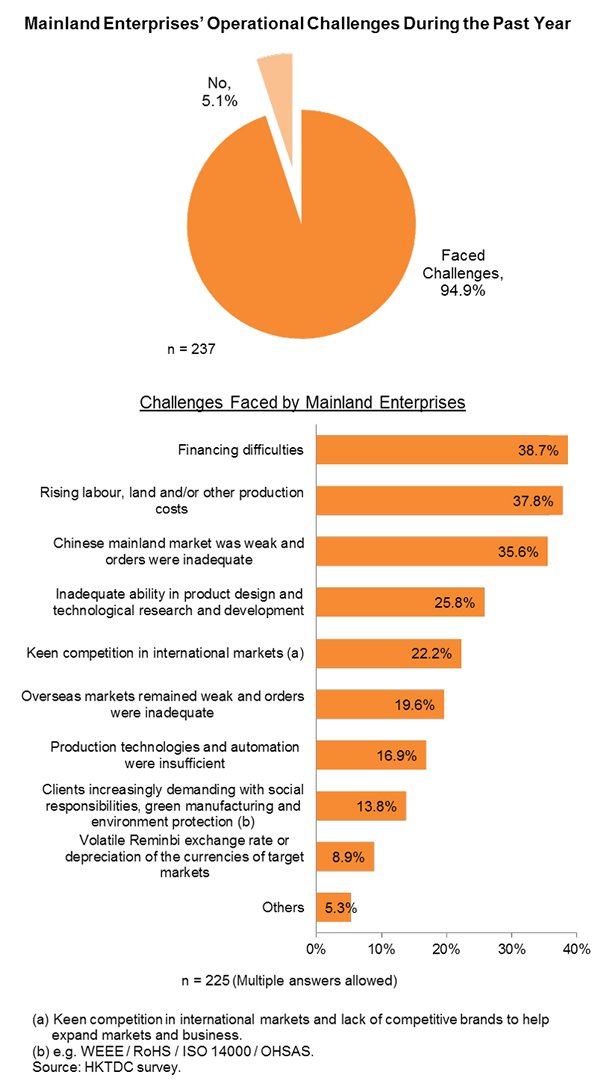

Of the enterprises surveyed, 96% said they had come across different types of challenges in their operations in the past year. The three main problems they faced were (1) difficulties in financing; (2) rising labour, land and/or other production costs; and (3) a weak mainland market and inadequate orders. These accounted for 39%, 38% and 36%, respectively, of the enterprises surveyed.

In addition, 26% of the enterprises indicated they were worried about their lack of capability in product design and technological R&D; 22% pointed out that, in the face of keen competition in the international markets, they lacked competitive brands to help develop international markets and business; and 20% said they were affected by weak international markets and inadequate orders. By comparison, relatively few enterprises (only 9% of those surveyed) said the volatile renminbi exchange rate, including depreciation of the currencies in their target markets, was a hindrance.

-

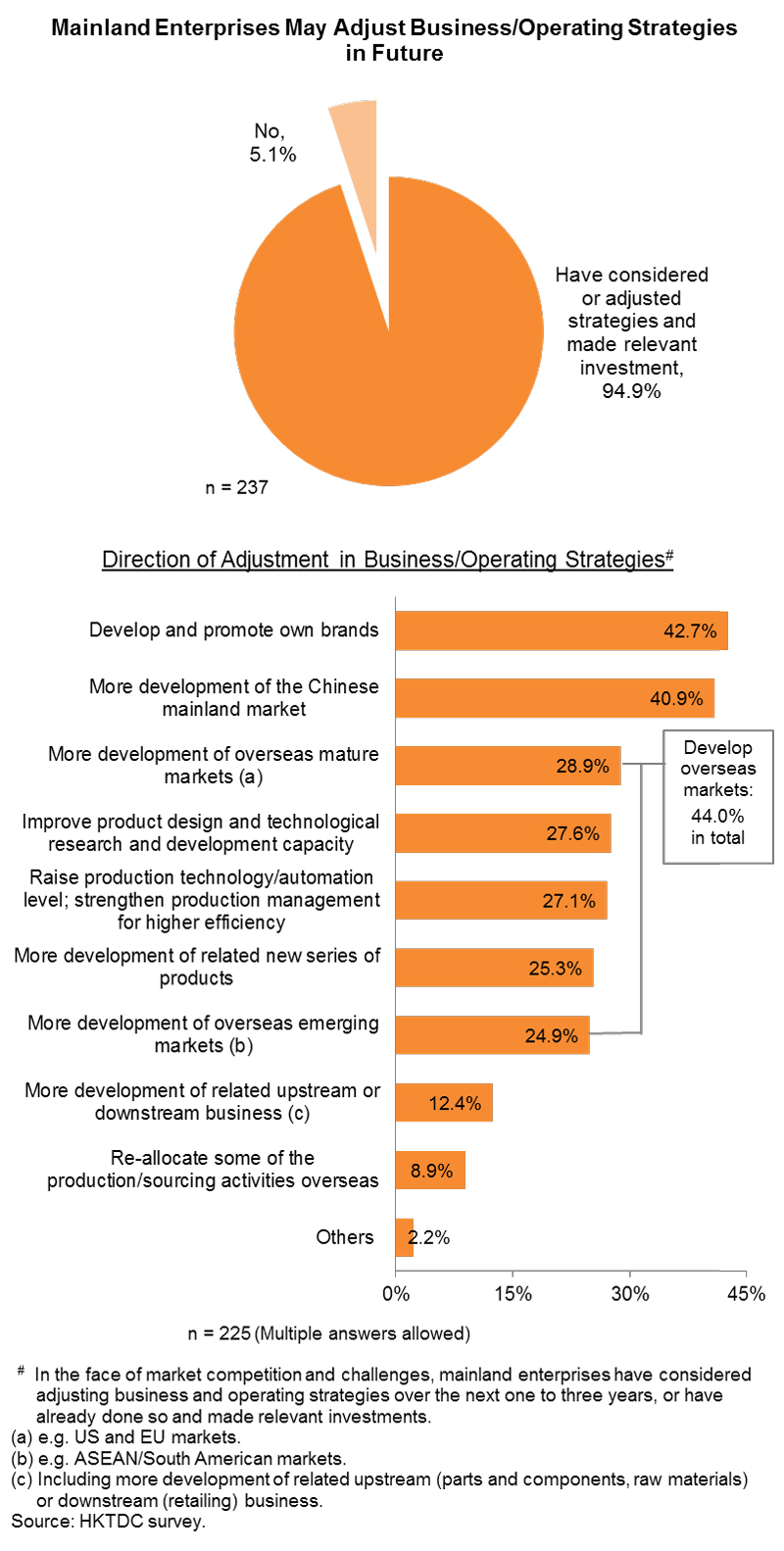

Adjusting Operating Strategy

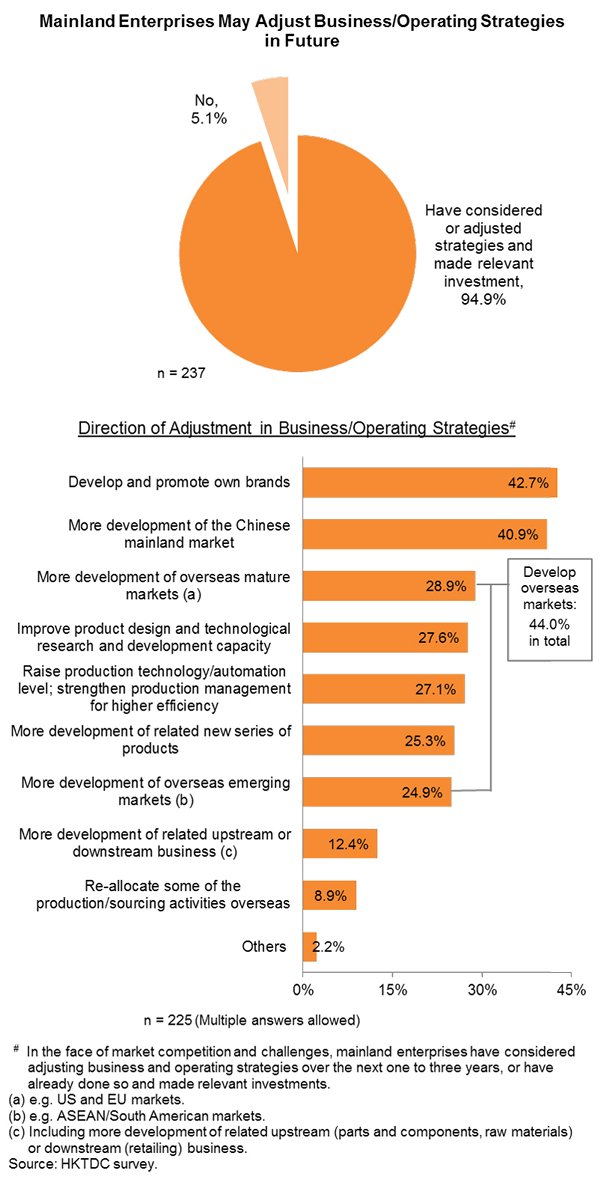

Confronted with market competition and other challenges, 95% of the enterprises surveyed said they had already adjusted their business and operating strategies and made relevant investment, or would consider doing so in the next one to three years. As to the direction of adjustments in business and operating strategies, most enterprises indicated they would do more to develop overseas markets, accounting for 44% of all enterprises surveyed (including 29% saying they would do more to develop overseas mature markets and 25% saying they would do more to develop overseas emerging markets). In addition, 43% said they would develop/strengthen their own-brand business, while 41% said they would like to do more to develop the Chinese mainland market.

Compared with the results of previous surveys, enterprises in western China appeared to be as keen as their PRD counterparts in wanting to develop both overseas markets and the Chinese mainland market. In comparison, enterprises in the YRD and Bohai Rim regions were more concerned with bringing in foreign advantages to develop the mainland market, showing that the development strategies of enterprises in different regions were not all the same.

-

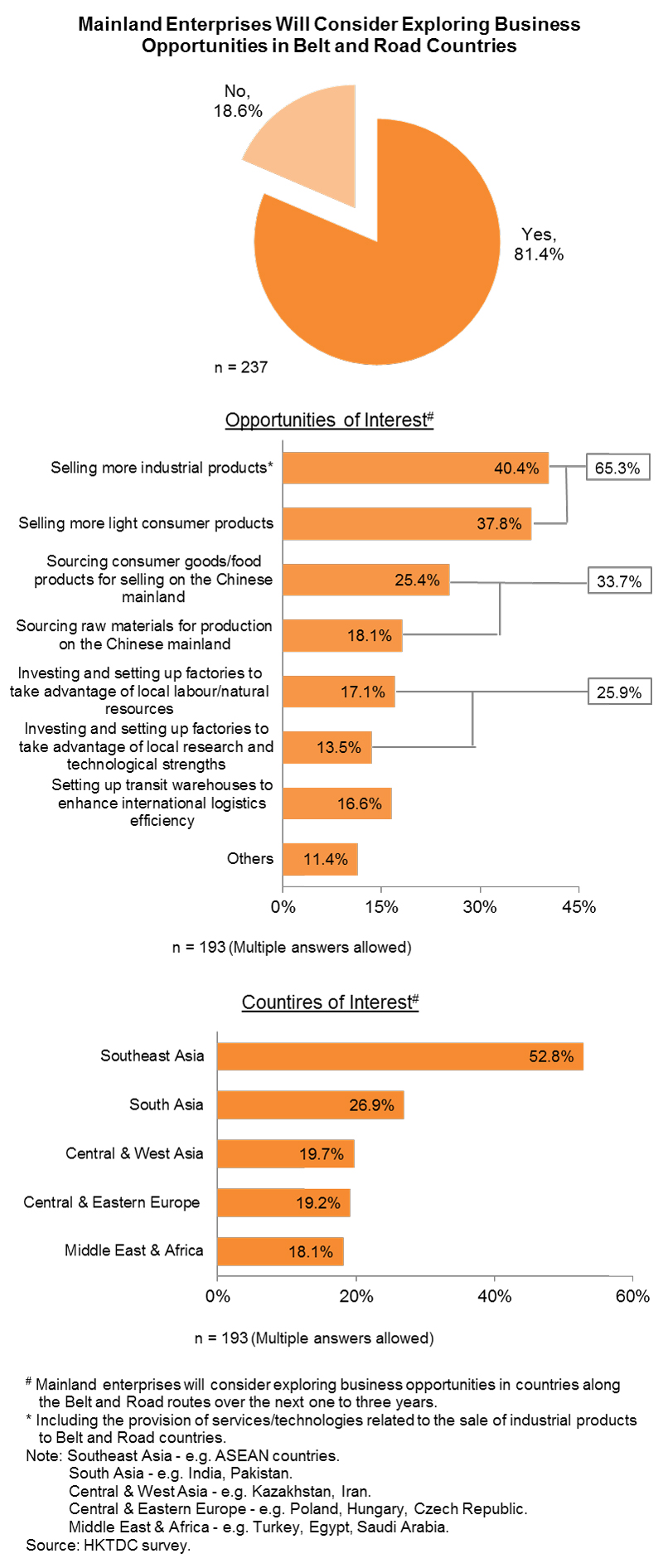

Intention of Tapping Belt and Road Opportunities

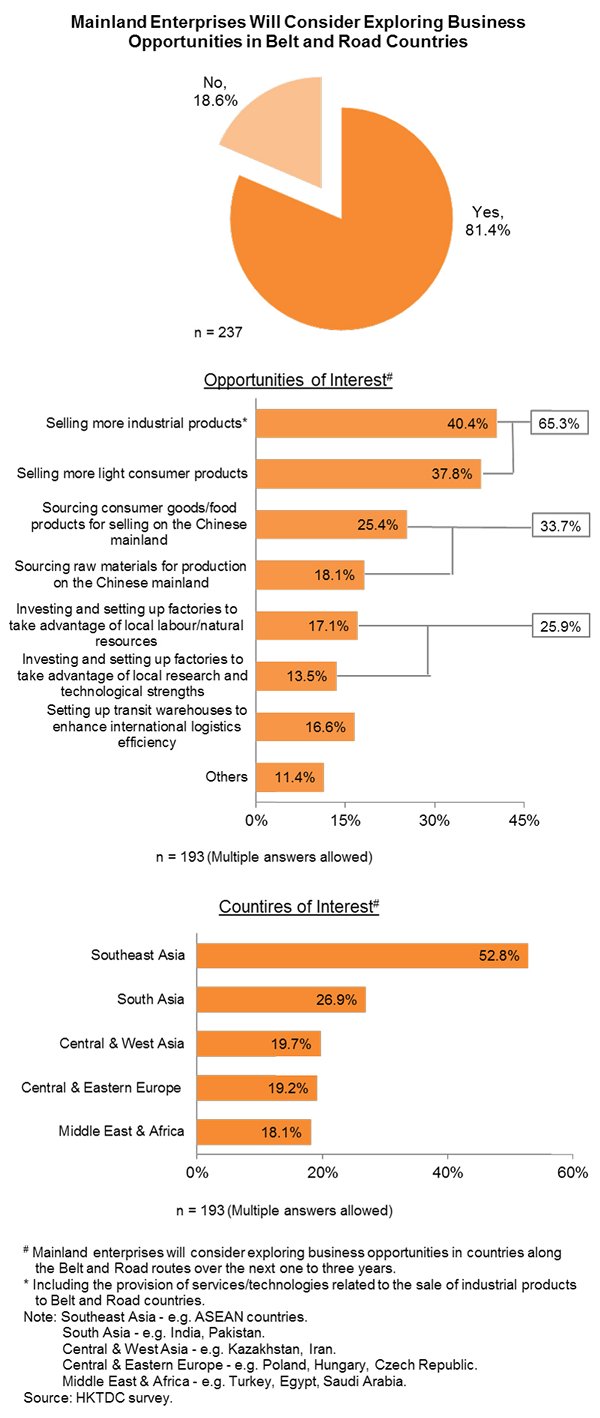

In the current survey, enterprises were also asked about their opinion on Belt and Road opportunities. Among all the enterprises surveyed, 81% said they would consider tapping opportunities in countries along Belt and Road routes in the next one to three years. Among these enterprises, most (65%) said they would like to sell more industrial products and light consumer goods to Belt and Road markets. A smaller proportion of the enterprises (34%) would like to go to Belt and Road countries to carry out sourcing activities, including the sourcing of consumer goods/food products to sell in the mainland market or the sourcing of raw materials for production on the mainland. Some enterprises (26%) would like to invest and set up factories in Belt and Road countries. In addition, 17% would like to set up transit warehouses in overseas locations including Belt and Road countries to enhance international logistics efficiency.

On the other hand, more than half of the enterprises (53%) said they would be most interested in going to Southeast Asia, such as ASEAN countries, to tap Belt and Road opportunities. Other locations of interest included South Asia (27%), Central and West Asia (20%), Central and Eastern Europe (19%) and the Middle East and Africa (18%).

-

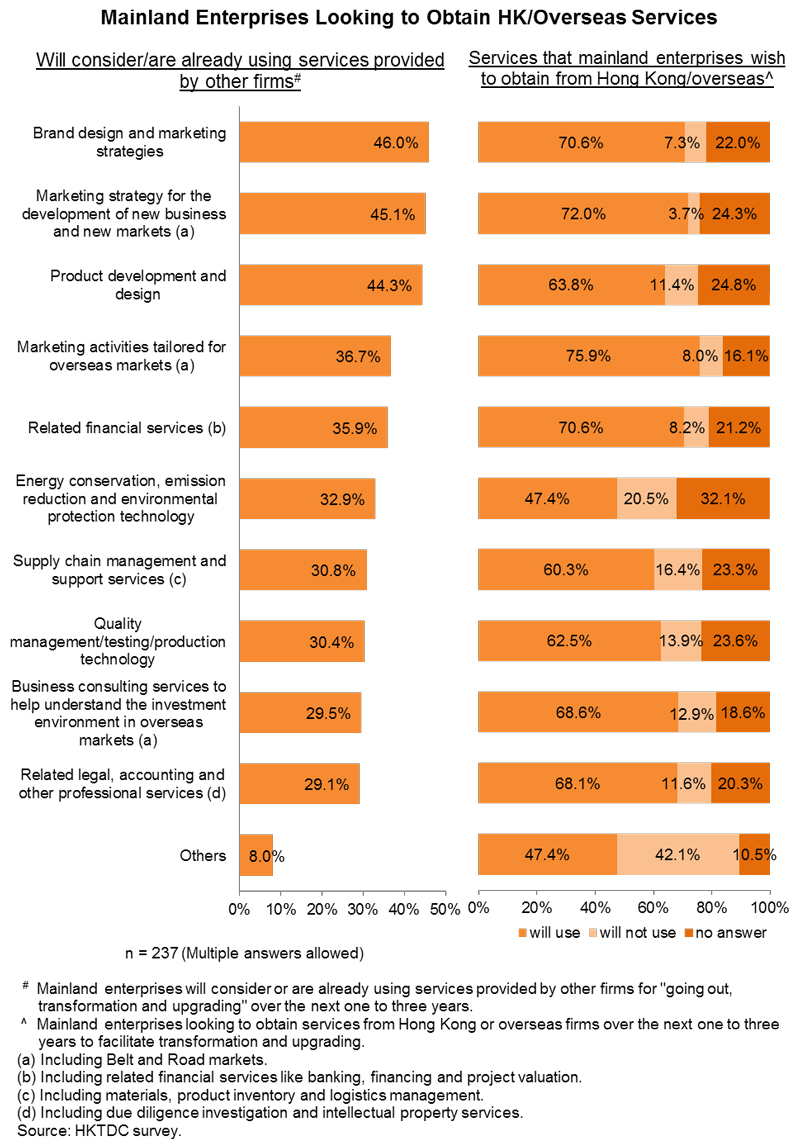

Keen Demand for Hong Kong and Overseas Services

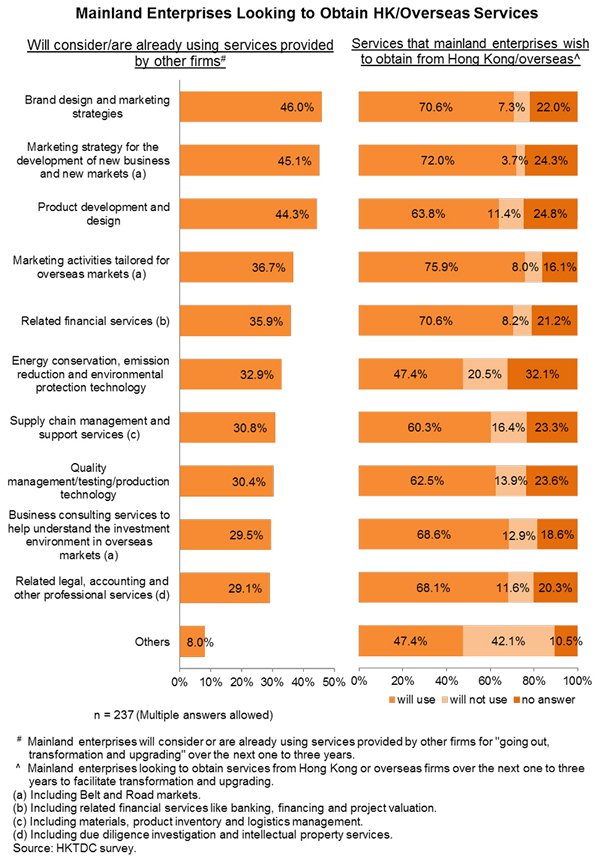

Facing all types of business and operating challenges and aiming to advance transformation and upgrading, the enterprises surveyed were keen for various types of professional services. In line with the results of HKTDC’s surveys conducted previously in the PRD, YRD and Bohai Rim regions, the three main types of services most sought by western China enterprises were: (1) brand design and promotion strategy; (2) marketing strategy for the development of new business and new markets (including the development of Belt and Road markets); and (3) product development and design. These accounted for 46%, 45% and 44%, respectively, of the enterprises surveyed. This shows that, irrespective of the direction of transformation and upgrading of mainland enterprises or the focus of their operating strategies, the professional services needs of enterprises from different regions are more or less the same.

Other services western China enterprises need to seek from the outside included: marketing activities tailored to overseas markets, including Belt and Road markets (37%); financial services such as banking, financing and project valuation (36%); services in energy conservation, emission reduction and environmental protection technology (33%); and supply chain management and support services, such as materials and product inventory and logistics management (31%). Of those enterprises surveyed requiring these services, more than 60% indicated they would use the services provided by Hong Kong or overseas suppliers, with the exception of energy conservation and environmental protection technology.

-

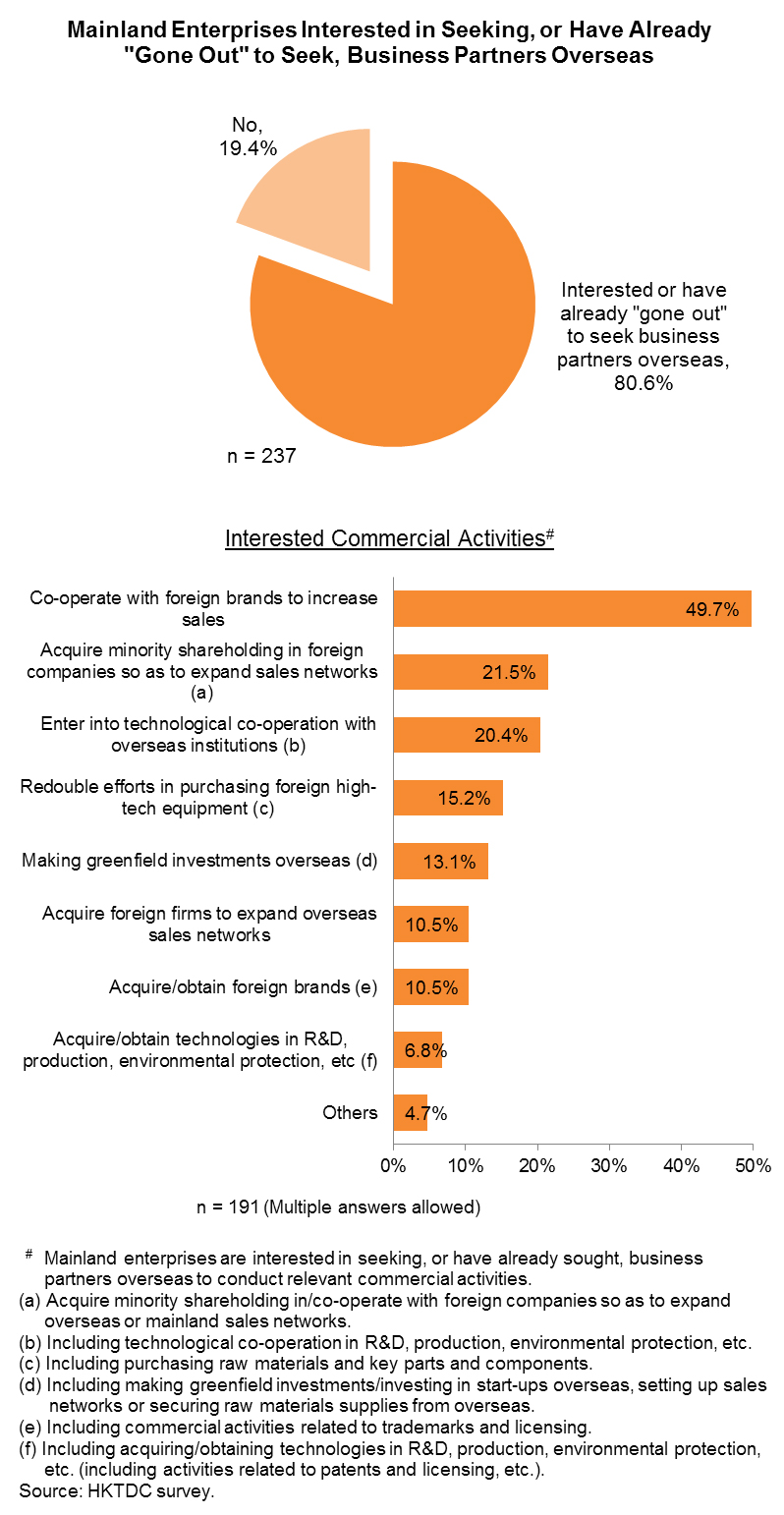

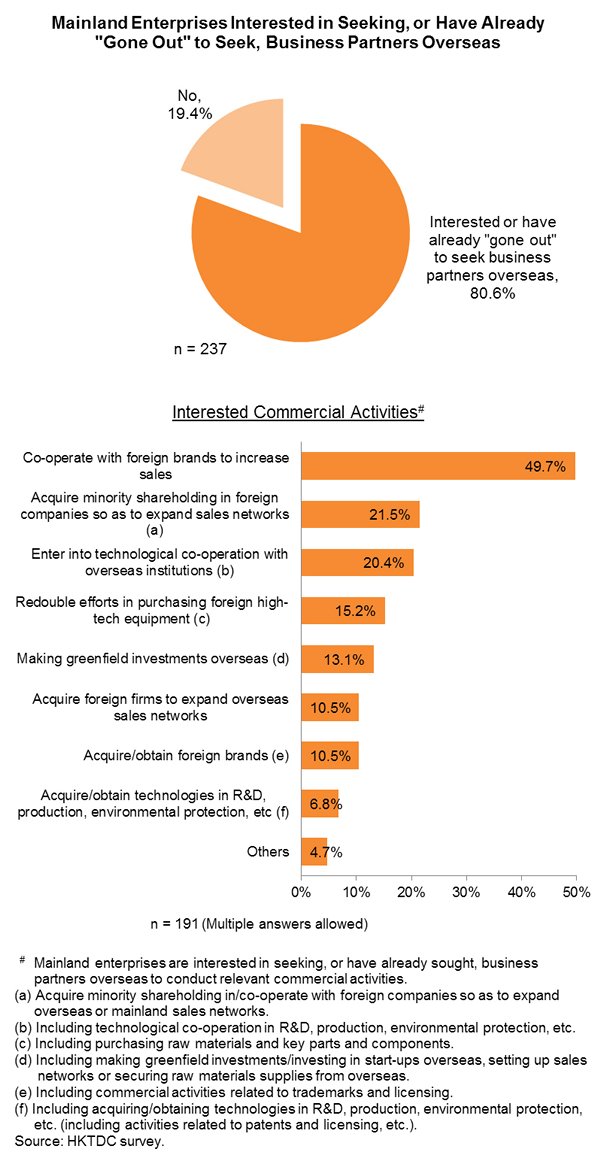

“Going out” To Seek Business Partners

Meanwhile, 81% of the enterprises surveyed expressed an interest in seeking, or had already “gone out” to seek, business partners overseas. The majority of the enterprises (about 50%) said they were interested in co-operating with foreign brands to increase sales. This is similar to the results from the surveys previously conducted in the PRD, YRD and Bohai Rim regions. (Coincidentally, enterprises from different regions considered brand co-operation as their top reason for seeking foreign partners.)

In addition, 22% of the western China enterprises surveyed said they would like to acquire minority equity stakes in foreign companies to expand their overseas/mainland sales networks, 20% would like to enter into technological co-operation with overseas institutions, while 15% would like to redouble their efforts in purchasing high-tech equipment, raw materials and key parts and components from overseas.

-

Hong Kong as the Preferred Services Platform for the Mainland’s “Going Out”

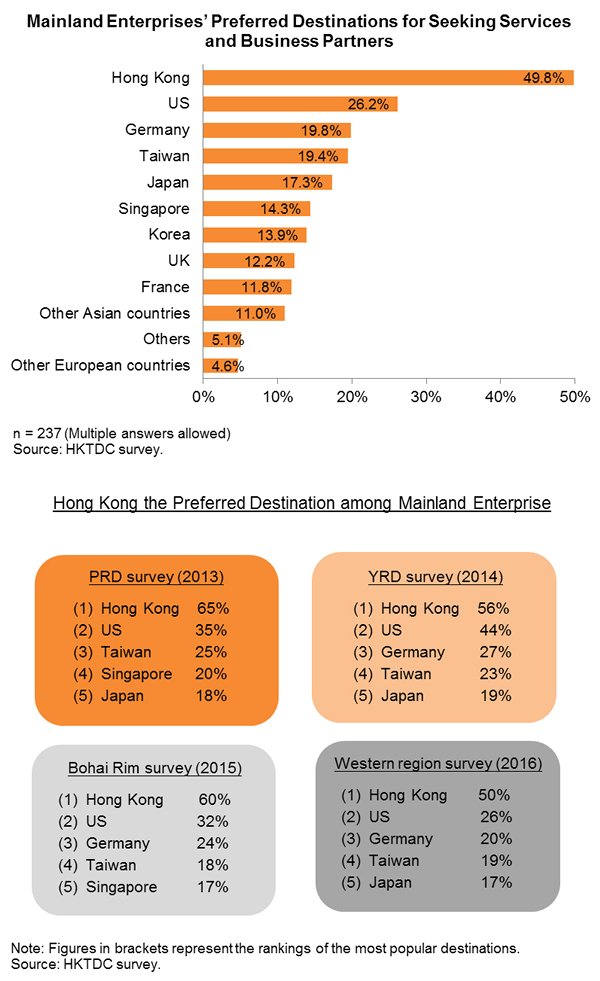

About half (50%) of the enterprises surveyed indicated they would like to go to Hong Kong to seek the professional services mentioned above and/or to look for foreign business partners. Although this proportion is slightly lower than in the previous three surveys, Hong Kong remains the “going out” platform preferred by most western China enterprises, and attracts the preference of a much higher proportion of enterprises surveyed than other locations such as the US, Germany, Taiwan, Japan and Singapore, which account for 26%, 20%, 19%, 17% and 14%, respectively, of the enterprises surveyed. It is therefore apparent that, irrespective of the location of a mainland enterprise or whether it is from the PRD, YRD, Bohai Rim or China’s western region, Hong Kong is the preferred services platform for “going out” from the mainland.

[1] The 13th Five-Year Plan refers to the Outline of the 13th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China adopted at the fourth session of the 12th National People’s Congress in March 2016.

[2] World Investment Report 2016, UNCTAD.

[3] Source: 2014 Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment.

[4] For the research topics and results of the surveys conducted respectively in the PRD, YRD and Bohai Rim, please see Guangdong: Hong Kong Service Opportunities Amid China’s “Going Out” Strategy published in December 2013; China’s “Going Out” Initiative: Jiangsu/YRD Demand for Professional Services published in September 2014; and China’s “Going Out” Initiatives: Professional Services Demand in Bohai published in September 2015.

[5] The HKTDC held a SmartHK Expo fair at Chengdu Century City New International Exhibition & Convention Centre on 12-13 May 2016. During the CEO Forum and four thematic seminar sessions related to “going out” to tap Belt and Road opportunities, HKTDC Research conducted a questionnaire survey on the attendees. Of the 469 questionnaires collected afterwards, 237 were deemed to be effective ones filled out by mainland enterprises (including trading companies, manufacturers and service suppliers).

[6] The options in the current survey are slightly different from those in the three previous surveys, so only some of the results can be compared.

| Content provided by |

|

Editor's picks

Trending articles

2 Aug 2016

‘One Belt and One Road’: Connecting China and the world

By Tian Jinchen (Director of the Western Development Department of China’s National Development and Reform Commission)

China is leading the effort to create the world’s largest economic platform. More than 2,000 years ago, China’s imperial envoy Zhang Qian helped to establish the Silk Road, a network of trade routes that linked China to Central Asia and the Arab world. The name came from one of China’s most important exports—silk. And the road itself influenced the development of the entire region for hundreds of years.

In 2013, China’s president, Xi Jinping, proposed establishing a modern equivalent, creating a network of railways, roads, pipelines, and utility grids that would link China and Central Asia, West Asia, and parts of South Asia. This initiative, One Belt and One Road (OBOR), comprises more than physical connections. It aims to create the world’s largest platform for economic cooperation, including policy coordination, trade and financing collaboration, and social and cultural cooperation. Through open discussion, OBOR can create benefits for everyone.

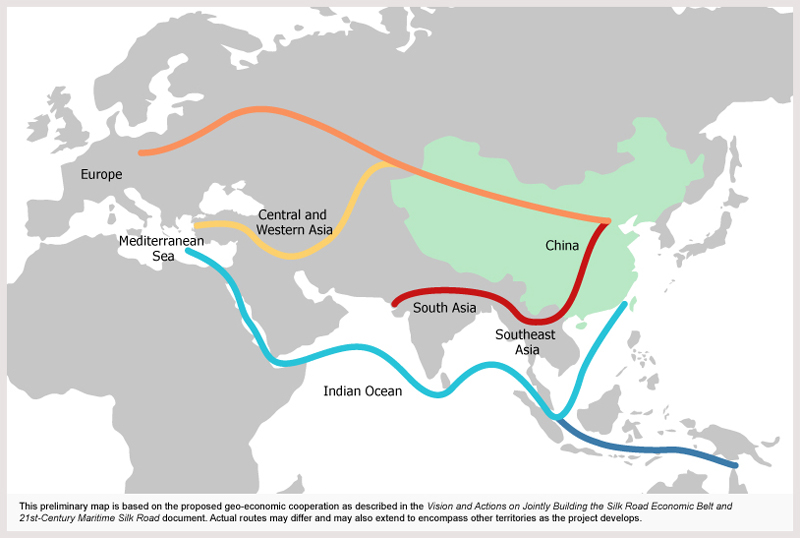

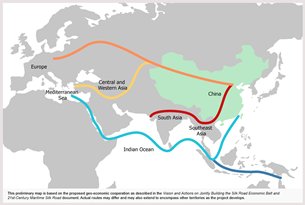

The State Council authorized an OBOR action plan in 2015 with two main components: the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (exhibit included in original). The Silk Road Economic Belt is envisioned as three routes connecting China to Europe (via Central Asia), the Persian Gulf, the Mediterranean (through West Asia), and the Indian Ocean (via South Asia). The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road is planned to create connections among regional waterways. More than 60 countries, with a combined GDP of $21 trillion, have expressed interest in participating in the OBOR action plan.

The effort has already made some practical achievements. China has signed bilateral cooperation agreements related to the project with Hungary, Mongolia, Russia, Tajikistan, and Turkey. A number of projects are under way, including a train connection between eastern China and Iran that may be expanded to Europe. There are also new rail links with Laos and Thailand and high-speed-rail projects in Indonesia. China’s Ningbo Shipping Exchange is collaborating with the Baltic Exchange on a container index of rates between China and the Middle East, the Mediterranean, and Europe. More than 200 enterprises have signed cooperation agreements for projects along OBOR’s routes. In 2014, China established the $40 billion Silk Road Fund to finance these initiatives, and it has made investments in several key projects. These projects are just the start as OBOR enters a new stage of more detailed and comprehensive development. This work will see the development of six major economic corridors, including the New Eurasian Land Bridge, China–Mongolia–Russia, China–Central Asia–Western Asia, Indo-China Peninsula, China–Pakistan, and Bangladesh–China–India–Myanmar. These corridors will be the sites of energy and industrial clusters and will be created through the use of rail, roads, waterways, air, pipelines, and information highways. By both connecting and enhancing the productivity of countries along the new Silk Road, China hopes the benefits of cooperation can be shared and that the circle of friendship will be strengthened and expanded.

China seeks to take the interests of all parties into account so as to generate mutual benefits, including environmental management and closer cultural exchanges. We wish to give full play to the comparative advantages of each country and promote all-around practical cooperation.

This article was originally published by McKinsey & Company’s Global Infrastructure Initiative, www.globalinfrastructureinitiative.com.

©McKinsey & Company 2016 All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

Please click here for the full article.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

4 Aug 2016

Navigating the New Silk Road - Executive Summary from the inaugural Belt and Road Summit

This Executive Summary is jointly produced by the Hong Kong Trade Development Council and McKinsey & Company.

In 2013, China’s President Xi Jinping outlined sweeping proposals aimed at reviving ancient trading routes between Asia, Europe and beyond, through the creation of an overland “Silk Road economic belt” and a “21st century maritime Silk Road.” President Xi’s “Belt and Road Initiative,” perhaps the most ambitious development programme put forward by China, would encompass some 65 countries in Asia, Europe and Africa, which collectively include 4.4 billion people and claim a gross domestic product of US$21 trillion.

As a key driver of this plan, the Chinese government has agreed to underwrite the development of infrastructure in Belt and Road countries through multilateral institutions and policy banks as well as China’s state-owned firms. In 2014, China established three new financial entities, two with international support: the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which includes 57 founding members and has a registered capital of US$100 billion; the New Development Bank, also known as the BRICS bank, and which includes Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, with an initial capital of US$50 billion; and the Silk Road Fund, financed primarily from China’s foreign reserves, with an initial capital of US$40 billion. Furthermore, China’s two policy banks, the China Development Bank and the China Export-Import Bank, are expected to provide substantial funding for Belt and Road-related projects, as are large state-owned lenders such as the Bank of China.

In spite of these resources however, the vast scope of the Belt and Road Initiative leaves ample opportunity for participation by other governments and the private sector. To explore these opportunities, the first ever “Belt and Road Summit” was held in Hong Kong on 18 May 2016, organised by the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and supported by China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Commerce and the People’s Bank of China, in association with the Hong Kong Trade Development Council. The honourable presence of Mr Zhang Dejiang, Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress of China, together with the support of the four Chinese ministries, is the first official endorsement of Hong Kong’s position and roles in the Belt and Road Initiative.

This definitive event brought together more than 2,400 government officials, business leaders and experts from around and beyond the Belt and Road economies for a day of discussion, debate and business-matching. It demonstrated Hong Kong’s ability to host a truly international business forum to facilitate the Initiative.

Why Hong Kong? We believe that Hong Kong is the ideal springboard to begin your exploration of Belt and Road business opportunities. As Asia’s financial and logistics hub, Hong Kong has a history in international trade, a stable legal system

and free flow of capital, information and people – all of which make our city the ideal place to commercialise opportunities from the Initiative.

To help you navigate the Belt and Road, we are pleased to bring you this report, which highlights some of the Summit’s proceedings and identifies major themes and areas for further consideration. Beyond the event, you can also visit our resource portal www.beltandroad.hk for further information on the Belt and Road, insights from business leaders and policymakers and a database of relevant advisors who can help.

In ancient times, the Silk Road connected people, created new opportunities and advanced development of nations through trade, commerce and cultural exchange. Likewise, we hope the Belt and Road Initiative will do all these and more. Beginning with the Belt and Road Summit, we invite you to join us on this momentous journey together for many decades to come.

Vincent H S Lo, GBS, JP

Chairman

Hong Kong Trade Development Council

Please click to read full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

5 Aug 2016

China's One Belt One Road Opportunities for Australian Industry

By Australia-China One Belt One Road Initiative (ACOBORI)

This report presents a practical outline of China’s new Belt and Road Initiative (otherwise known as One Belt One Road) and the complementary role government and business can play in its implementation. The messages contained within this report are intended to provide representatives of Australia’s industries and professional services with a better understanding of current Belt and Road projects. As well as provoke a level of enquiry and consideration about the breadth and depth of capability that Australia could contribute to the implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative.

The Belt and Road Initiative aspires to increase regional cooperation and economic development with countries along the identified Silk Road routes. Beyond this geographical area, China views the Initiative as an inclusive framework, where participation will not be limited to a particular country or region, but rather offer a global model for international engagement.

Therefore, if appropriately curated and understood by both Australia and China, there will be avenues for Australian businesses to take part and benefit from the implementation of the Initiative – specifically:

1. Australian businesses could use the framework of the Initiative to attract Chinese partners in major Australian based projects (which may also involve commonwealth and state government interaction/regulatory compliance);

2. Australian businesses could use the framework of the Initiative to partner with Chinese enterprises in projects beyond Australia – both in China and in Belt and Road countries.

To participate however Australian industries and professions need to further capitalise on a strong trading relationship with China. This requires not only to reinforce the strengths of traditional trading sectors, but also to use the scope of the Initiative to identify other industry sectors where Australian businesses can bring comparative or competitive advantage…

With the link to download this report, you can use www.australiachinaobor.org.au. The current copy you have is a partial report, people can follow the link to our website to request full copy or even hard copy of this report to be posted to them.

Please click here for the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

"Going Out" to Capture "Belt and Road" Opportunities (Expert Opinion 4): Cross-Border Financing Serving Outbound Investment

As an important business platform of the Asia-Pacific region, Hong Kong boasts many advantages, including a sound legal system, free movement of funds and information, and all kinds of legal/accounting and other professional services. Conrad Tsang, Chairman of the PRC Committee of the Hong Kong Venture Capital and Private Equity Association (HKVCA), pointed out that mainland companies may absorb external capital through Hong Kong for their overseas projects and other operations when investing in countries along the Belt and Road. Leveraging Hong Kong's strengths as regional headquarters, they may also make use of the territory's efficient business environment to coordinate investments in the mainland, Asia and other Belt and Road markets and boost the efficiency of "going out" as a whole.

Financing Overseas Investment Projects

In an interview with the HKTDC Research, Conrad Tsang said: "Unlike startups that need the support of seed or angel funds, mainland companies planning to 'go out' and invest abroad have grown to a considerable scale and have good assets and cash flow. This notwithstanding, most of them still need financing for their overseas projects and need to seek sufficient funds to support the development of these projects.

"Hong Kong's low tax rate and relatively simple tax system, well-developed financial infrastructure and efficient communications networks have attracted many venture capital and private equity funds to set up offices in the territory. Many of these are managing the funds of local investors, but a good part of them have funds from all over the world.

“On the one hand, they make use of Hong Kong networks to develop mainland-related investment projects, on the other hand, they also take advantage of Hong Kong's position as their regional headquarters to seek investment opportunities and manage investment projects in the Asia-Pacific region. Their business covers Southeast Asian countries like Vietnam, Malaysia and Thailand, Central Asia and even Russia and other countries along the Belt and Road. With China 'going out' to expand business with countries along the Belt and Road, there is plenty of room for cooperation between Hong Kong's venture capital and private equity firms and China's 'going out' enterprises."

Hong Kong is an international financial centre, with a low tax rate, convenient business environment and other advantages. Geographically it lies next to the rapidly developing Asian region as well as mainland China, which has already become a major world economy.

As such, it is attracting international venture capital and private equity firms eyeing opportunities in the Asia-Pacific markets to shift their regional headquarters to the territory. They make use of Hong Kong's information resources and networks to find investment opportunities in the mainland, Asia and even countries along the Belt and Road and engage in fund raising and other financing activities. They also make use of Hong Kong's professional services to handle accounting, contract, legal and other matters, manage their business presence in the mainland and other regions, and secure and conclude investment deals locally.

Injecting International Elements in Going Out Enterprises

Tsang believes that Hong Kong is attractive in part due to its freedom from some of the business obstacles encountered elsewhere. He said: "Mainland companies often need foreign currency capital to finance their operations when developing business abroad, including establishing sales networks, carrying out direct investment, and engaging in purchases and all kinds of acquisitions. At present, they are still subject to many restrictions in trying to raise capital for overseas projects through domestic channels.

“Through Hong Kong's business platform and its advantage in the movement of capital, mainland companies can effectively overcome investment and financing hurdles in their overseas ventures. In fact, Hong Kong's venture capital and private equity investors can not only help in equity funding but can also inject international elements into mainland companies. Through their international corporate structure in Hong Kong, they can carry out cost-effective equity and debt financing for outbound investment projects and support the development and operation of these projects.

“Investors from all over the world converge in Hong Kong and venture capital and private equity firms with footholds in Hong Kong have become important clusters of investors in the Asia-Pacific region. They can effectively assist ‘going out’ mainland companies investing in projects along the Belt and Road.”

HKVCA currently has over 340 corporate members, including 190 private equity firms, and manages a total of US$1 trillion in assets. These firms are engaged in venture, growth, buyout and other funds in the Asia-Pacific region.[1] A total of US$67 billion in private equity funds were raised in Asia last year, about 18% of which were gathered in Hong Kong. There were 354 private equity entities with headquarters in Hong Kong as of the end of 2015.[2]

[For examples of how Hong Kong investors can help mainland companies in "going out", please see: “Going Out” to Capture “Belt and Road” Opportunities (Expert Opinion 5): A Co-investment Example of Going Global]

[1] Source: HKVCA.

[2] Source: Asian Venture Capital Journal/data quoted by the Hong Kong SAR government.

| Content provided by |

|

Editor's picks

Trending articles

9 Aug 2016

Infrastructure Financing Trends

By International Finance Corporation, World Bank Group

What are the Current Trends in Emerging Market Infrastructure Spending?

Emerging markets need twice the infrastructure investment they now receive. East Asia has the greatest needs, while Africa’s requirements are large in comparison to its economic size; power generation accounts for more than half of needed investment. There is great potential for increasing participation by institutional investors in developing-country infrastructure: Insurance companies, asset managers, pension funds and sovereign wealth funds are increasingly aware of the manifold benefits that infrastructure investments offer.

Emerging markets can absorb an estimated $2 trillion per year in infrastructure spending, about half of which currently goes unmet. And the gap will only grow, as infrastructure investment needs in emerging economies are expected to double annually over the next decade.

Government budgets are the biggest source of funds, accounting for about three of every four infrastructure dollars, while the private sector provides the rest. Yet in the aftermath of the financial crisis, governments have seen their fiscal deficits grow and their budgets shrink, increasing the need for private funding. However, most private funding flows to upper middle-income countries.

Going forward, East Asia including China will require the majority of infrastructure investment; Sub-Saharan Africa’s needs are substantial relative to the size of the region’s economies. In terms of sectors [1], electricity will require over half of all infrastructure spending. That includes power generation, capacity, and transmission and distribution networks. And preparation costs, including design and arranging financial support, are not insignificant—they can constitute up to 10 percent of overall project costs.

Debt represents about three-quarters of total private financing for infrastructure, with loans about 1.5 times the size of bonds. Before 2008, international loans had been the main infrastructure funding source. Since then international lending has slowed and local loans and bonds have filled the gap. International instruments rebounded in 2013, though primarily due to a few large transactions in limited sectors in Mexico, China, and Brazil.

Private Participation

Private participation in emerging-market infrastructure hit a high in 2012. The Latin America/Caribbean region was the largest recipient, while South Asia and East and Central Asia have tended to be high volume destinations as well. At a country level there is a concentration in the BRICs—Brazil, Russia, India, and China—plus Turkey and Mexico. Between 2000 and 2013 some 38 percent of private flows went to Brazil and India. Still, despite the increase in private investment in infrastructure since 2008, most of the gains flowed to upper-middle income countries, while flows to lower-middle and low income countries fell by 37 percent and 68 percent, respectively, between 2007 and 2013. At a sector level, private investment is concentrated in the energy and information technology sectors.

Insitutional Investors

Insurance companies, asset managers, pension funds, and sovereign wealth funds are all attracted to infrastructure because it offers diversification potential and inflation and interest rate protection—and it contributes to public goals. As a result, and despite the current small allocation to infrastructure by these market participants, private infrastructure investments are increasingly attracting interest from institutional investors. In addition, more investors are entering the space via debt, co-investments and secondaries, and less through direct investment.

Please click here for the full report.

[1] Infrastructure sectors covered: energy, water and sanitation, transport, and telecom. Estimates were conducted using various sources, including PPIAF, Dealogic, and Project Finance Review. Source for spending data: Bhattacharya and Romani, “Meeting the Infrastructure Challenge, 2013.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

12 Aug 2016

Six Challenges for US-Japan Cooperation in Asia

By Hitoshi Tanaka, Senior Fellow, Japan Center for International Exchange

A new year has come, but it seems clear that in 2016, the regional order in East Asia will continue to be characterized by a sense of instability. China’s behavior continues to create unease, most prominently through its unilateral construction of artificial landfill islands in the South China Sea, but also through the progress it is making on its regional economic initiatives, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the One Belt, One Road infrastructure connectivity plan. Meanwhile, the shadow of Crimea hangs over Russian dealings with Asia, and North Korea has yet again tested a nuclear device.

A key question as 2016 progresses will be a familiar one: How best to focus US-Japan cooperation to address both the challenges and opportunities that accompany the rise of China? The time is ripe for intensive alliance consultations regarding future cooperation with China given the relative improvement of Sino-Japan relations over the last year. At the same time, there are six thorny issues that carry the potential to undermine US-Japan cooperation and thus need to be dealt with. Close, careful US-Japan consultation and cooperation is required to ensure that these issues do not create a wedge in the alliance.

1. The Future of US Global Leadership

The world is watching the US presidential election closely for signs of the foreign policy path the next US president will take. A significant amount of the rhetoric from the primaries is concerning—most notably the xenophobic remarks of Donald Trump, which have captured the media spotlight. While it is still a long road to the White House, the kind of debate we have seen so far—which has taken a hostile tone toward certain nations and groups (such as banning Muslims from entering the United States) and has failed to recognize the vital need for international cooperation—is damaging to the long-term credibility of US global leadership. Continued US leadership is critical to maintain and strengthen liberal and free-market values as well as the stability and prosperity of East Asia. The United States, East Asia, and the world need a US president with the stomach for strong global leadership based on deep cooperation and consultation with US allies and partners, rather than one who advocates unilateralist or isolationist thinking.

2. Regional Trade Deals and Economic Governance

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) deal reached in October 2015 has rightly been hailed as a major achievement in setting common rules for regional economic governance. Now the agreement must be ratified by the 12 signatory states, including the US Congress. In light of China’s efforts to launch the AIIB, roll out the One Belt, One Road initiative, and reach a Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership with the ASEAN+6 nations, the TPP is critical to the future credibility of US regional leadership. The TPP is not simply a vehicle to facilitate increased trade, but rather a means to shape 21st-century rules for economic governance and to promote and entrench liberal free-market principles in Asia Pacific.

Indonesia’s decision in September 2015 to choose China over Japan to build a high-speed train line between Jakarta and Bandung is illustrative of what is at stake. The US$5.5 billion Chinese proposal was attractive given that it required neither financing nor a loan guarantee from the Indonesian government; in other words, China is taking on almost all of the financial risk of the project, which most ODA providers are not able to do. Three-quarters of the funding will come from China and the remaining 25 percent from Indonesian companies. Indonesian President Joko Widodo, who campaigned on improving welfare for ordinary Indonesians, was thus able to avoid using the national budget for a project in one of the country’s most prosperous areas. But many questions remain regarding the transparency of the proposal and the ability of China to meet international standards, including on labor and environmental regulations. There is already local criticism of the project for its plans to use Chinese workers at a time when Indonesia’s unemployment rate is rising and there are concerns over China’s safety record in light of the crash of a high-speed train in Wenzhou in 2011.

It is thus critical that the United States, Japan, and the broader international community engage with Chinese-led economic initiatives, including the AIIB and One Belt, One Road project, to help steer China toward a greater embrace of international best practices. In this context, it is important to note that the TPP has an open-accession clause to create a clear and transparent process through which other countries—including China, Indonesia, and South Korea—can join in the future. The United States and Japan should actively promote the expansion of TPP membership, especially to these countries.

3. Demilitarizing the South China Sea

The construction of artificial landfill islands by China in the South China Sea in areas such as the Fiery Cross, Mischief, and Subi Reefs, which are also claimed by ASEAN nations, has set back efforts to peacefully negotiate a diplomatic resolution to these territorial disputes. Moreover, the potential for the future construction of a chain of airports, ports, and other facilities on the artificial islands, as well as high-profile attempts by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy to enforce no-fly zones, risks further militarizing the South China Sea. Such a scenario would be a serious security concern for the region and should be avoided.

One potentially complicating factor is the recent election in Taiwan, where the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) won a comprehensive victory, with Tsai Ing-wen winning the presidency and the party gaining the majority in the Legislative Yuan. The DPP is known for its pro-independence stance vis-à-vis Beijing and has in the past suggested negotiations between Taiwan and ASEAN nations over the South China Sea. Tsai has also questioned the “1992 consensus” that there is only “One China” with Beijing and Taipei simply maintaining differing interpretations. For the time being, Tsai seems to have settled for a loosely defined continuation of the status quo. But if the DPP government were to push Taiwan toward a more assertive foreign policy stance and articulate a South China Sea policy different from that of the mainland, it could further complicate the issue.

Further military build-up in the South China Sea will undoubtedly feed regional tensions and increase the risk of accidental conflict. Until a diplomatic resolution can be peacefully negotiated between China and the ASEAN countries, it is vital that all parties be alert to China’s incremental changes. At the same time, in addition to continued US freedom of navigation operations—to ensure free passage, uphold international law, and prevent any further unilateral changes to the status quo—the United States and Japan must coordinate and cooperate to persuade China that freedom of navigation in what is a vital sea route for international commerce and the energy security of East Asia, is a shared interest not just for the United States, Japan, and ASEAN countries but also for China itself.

4. North Korea

Four years since he inherited power from his father, Kim Jong-un appears to be drawing from a diverse toolbox to consolidate his grip on power. First, Kim is continuing the country’s nuclear weapons development program. On January 6, 2016, North Korea tested a nuclear device for the fourth time—the second under Kim Jong-un’s leadership. Such tests and rocket launches are a signal to domestic audiences, especially the Korean People’s Army (KPA), that Kim is capable of continuing the country’s technological progress and bolstering military might against hostile external forces. Second, Kim has also purged a number of high-level officials from his father’s cliques (most infamously his own uncle, Jang Song-thaek), replacing them with his own younger loyalists. Notably, these purges have tended to target military men rather than economic planners. Third, Kim has also shown interest in cementing his legitimacy through economic development. Experiments with reforms have taken place quietly in the background, allowing farmers to retain a fraction of their produce to sell on the market rather than being forced to sell everything to state distributors. Kim is also gearing up for the 7th Congress of the Workers’ Party of Korea (WPK), the first time such a meeting has been held in 36 years. It has been speculated that Kim may use the party congress as a platform to launch more serious economic reform measures and to reassert the primacy of the WPK over the KPA.

The region was rocked by North Korea’s most recent nuclear test. This time, the international community must go beyond business-as-usual measures to deal with the North Korean nuclear program. In order to truly alter North Korea’s behavior, economic sanctions, including financial sanctions, will need to be strengthened. Beijing has a big role to play. Irrespective of its apparent change in attitude after the third North Korean nuclear test in 2013, China has continued to provide substantive assistance to North Korea. For any form of sanctions to be effective, though, the international community as a whole, including China and Russia, must fully back them. South Korea, Japan, and the United States must deepen cooperation and adopt a unified approach on sanctions policy as well as on joint contingency planning. From a coordinated trilateral base, the three nations also need to consult with China and Russia to form a united five-nation front to apply greater pressure on North Korea. An immediate restart of the denuclearization process under the Six-Party Talks may be difficult, but without the right measures to pressure and isolate North Korea, nothing will be achieved and North Korea will continue to develop its nuclear arsenal.

5. Russia Policy

Since Vladimir Putin and Shinzo Abe both returned to power in 2012, the two leaders have built a certain rapport and have shown a willingness to deal with the issue of the Northern Territories (referred to as the Southern Kuril Islands in Russia). Putin was even scheduled to visit Japan. But then Russia annexed Crimea in March 2014 and summit plans were put on hold.

Since then, Japan has stuck to its international obligations and imposed sanctions against Russia in concert with the other G7 nations to punish Russia for its violation of international law. However, if it appears that an acceptable agreement can be reached on the Northern Territories, an issue that has blocked the normalization of Japan-Russia relations since the end of World War II, Japan will have no choice but to seize the opportunity. At the same time, it is important that the United States and Japan maintain very close coordination and not allow Russia to utilize the Northern Territories issue to drive a wedge between them. They must also make clear to Russia that any Russo-Japanese cooperation to resolve the Northern Territories dispute will not translate into an acceptance of the annexation of Crimea or any other violation of international law.

Recently, Prime Minster Abe has reportedly expressed the possibly of making a trip to Russia in his capacity as this year’s chair of the G7. There is also talk of a possible trip by Putin to Tokyo by the end of 2016. While continuing to advocate for a peacefully negotiated resolution to the Crimea crisis, given the possibility that the isolation of Russia could push Putin toward China, it may be wise not to preclude some forms of strategic cooperation with Russia in areas of overlapping interest—including on North Korea and Syria.

6. Reducing Okinawa’s Burden

The battle between the Okinawa prefectural government and the Japanese central government regarding the relocation of the US Marine Corps Futenma Air Station continues to intensify. Each side has launched a series of tit-for-tat court battles centering on the legality of the construction of a new base in Henoko to replace Futenma. Backed by their determined governor, Takashi Onaga, local Okinawan protestors are demanding at a minimum that no new bases be built in the prefecture, with a view to reducing the concentration of bases in Okinawa in the future.

The situation has reached something of an impasse. While the United States might be happy to leave this to the Japanese government to deal with as a domestic issue, ultimately the United States will also have to suffer the consequences of Okinawa’s local opposition. Deep US-Japan consultations must continue, which should be conducted as part of regularized reviews of the US forward deployment structure and how it relates to US-Japan alliance goals. There are two important points to keep in mind here. First, while a continued US forward deployment presence in Okinawa is critical to the maintenance of the alliance’s deterrence posture, if the situation is not handled with due sensitivity for local Okinawan concerns, base protests will continue to be a thorn in the side of alliance relations over the long term. Second, the overall US forward deployment posture in East Asia should be evaluated in light of advances in new military technologies and the need to respond to regional security challenges in a dynamic way. A more evenly rotated distribution of US soldiers across the region—a trend that is underway thanks to increased cooperation with partners such as Australia, India, the Philippines, Singapore, and Vietnam—would not only help reduce the burden on Okinawa over the long term, but also be strategically desirable in responding to a range of new threats.

The choices we make now, during this time of regional flux, about how to deal with these six challenges will go a long way toward determining the future regional order. With deep and regularized consultations across all aspects of the alliance—including on security, economic, and diplomatic strategy—not only can the United States and Japan (in conjunction with other allies and partners) deepen the foundation of their cooperation, but they can also guard more effectively against unilateral changes to the status quo and work together with China to steer its rise in a mutually beneficial direction.

Hitoshi Tanaka is a senior fellow at JCIE and chairman of the Institute for International Strategy at the Japan Research Institute, Ltd. He previously served as Japan's deputy minister for foreign affairs.

Reprinted with the permission of the Japan Center for International Exchange.

Please click here for the full report.

Editor's picks

Trending articles

“Going Out” to Capture Belt and Road Opportunities (Expert Opinion 5): A Co-investment Example of Going Global

Chinese mainland enterprises are increasingly looking to make direct investment overseas in order to explore new markets or to obtain access to labour or other resources. Companies have undertaken such moves on their account as well as via mergers and acquisitions. According to one Hong Kong-based investment house, however, equity co-investment or other forms of joint-stock partnership could provide additional options for those mainland investors who are eager to expand their overseas businesses while managing the risk involved. Through cooperation with co-investors, mainland enterprises could not only enjoy the benefits of risk sharing among the investment partners, but also be furnished with additional synergy that could help them move beyond their business constraints, thereby reaching new business frontiers through capitalising on the strengths of their co-investment partners.

Alternative Mode of Investment

Alex Downs is the Director of Ironsides Holdings Limited, a Hong Kong-based private equity investment firm that sources funds from Hong Kong, the US and other territories. The firm invests directly into private companies and projects in a number of areas, including health-care, agriculture, logistics and technology. Its current investments cover - among others - the Southeast and Central Asian regions, which are within the remit of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Interviewed recently by HKTDC Research, Downs said: “Chinese enterprises seem to prefer taking a controlling stake when conducting investment in overseas projects or companies. There is, however, always the choice for them to have a much bigger presence in the overseas markets and explore new business opportunities via cooperation with their foreign counterparts, something that could result in decent profits with reduced risks.

“Chinese enterprises could reduce their overseas investment risks by cooperating with experienced equity co-investment partners. With minority equity participation, these partners could effectively undertake feasibility studies, due diligence and long-term sustainability analyses for the cooperation projects in question. In the case of investment in certain emerging economies along the Belt and Road, further engagement of local or other experienced partners would be an option for those mainland investors concerned about the risks stemming from loose local regulations and immature legal systems, less transparent local ownership requirements, imperfect or partial local business and market information, troublesome labour arrangements and other cultural issues.

More importantly, via their co-investment partners, Chinese mainland enterprises could be given the option of enhancing their businesses beyond their original operations.” In this regard, Downs cited the example of an agricultural investment made last year. In this instance, Ironsides was heavily involved in helping the company to re-brand and re-focus its core business model as part of the investment programme. This helped the mainland enterprise expand its reach into the international market.

Downs also discussed a number of the current opportunities available to support heavy industry, such as coal mining operations on the Chinese mainland. In this instance, a co-investor could become a pivot, allowing the mainland mining operation to divert its excess capacity into investment projects in Southeast Asia. This could see them fundamentally refocus their company, with the help of experienced international partners, into new and profitable business projects beyond coal mining. Such co-investments could reduce the risk associated with investments, while also solving the overcapacity problem affecting many mainland companies. Ultimately, this would enable them to continue their operations and assure them of profitable growth.

Synchronising the Interests of Different Partners

Assessing the pro and cons, Downs said: “Ultimately, Chinese enterprises may not have the controlling stakes in such co-investment models, with success resting on the participants’ contributions and the effective cooperation among the partners. On the upside, the Chinese enterprises would be given the opportunity to participate in a bigger project and have access to markets beyond that of their original business, thus generating sustainable incomes from their overseas investment. This would be a viable option for those ‘going-out’ enterprises without enough experience, exposure and/or resources. Of course, they would have to determine whether to get a majority control in a smaller-scale project by sole investment or whether to take a smaller stake in a bigger project and go global with co-investment partners, and probably with lower risks.”

Downs noted that China is on course to solve its overcapacity problem, while looking along the Belt and Road to seek for further growth impetus. In this regard, private equity firms based in Hong Kong, such as Ironsides, would be able to help Chinese mainland enterprises to relocate their excess capacity via investment in Asia and other Belt and Road countries. This is down to the fact that investment firms in Hong Kong have the advantage of vast business connections both on the Chinese mainland and internationally. As a result, they have access to a variety of different companies, all of which are looking for growth opportunities.

With free flow of information and familiarity with Chinese and foreign business environment, Hong Kong investors have a considerable understanding of the business needs of a variety of mainland and overseas companies. They are thus in the ideal position to help combine the strengths and resources of Chinese and foreign partners, and to align their interests in order to jointly enter new markets, move up the value chain, and re-allocate resources, when required, to drive businesses forward.

| Content provided by |

|