Belt and Road Opportunities in Central and Eastern Europe

Central and Eastern European Countries (CEECs) have played an increasingly pivotal role in China’s foreign policy considerations and are key partners to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Cash-rich Chinese white knights have become highly sought-after by many struggling but promising CEE businesses, while generous funding for mega government-to-government (G-to-G) infrastructure projects and seed capital for start-ups are also providing valuable impetus to rejuvenate the CEE economy and restore its industrial and commercial prowess.

CEECs as a Key Partner to “16+1” and BRI

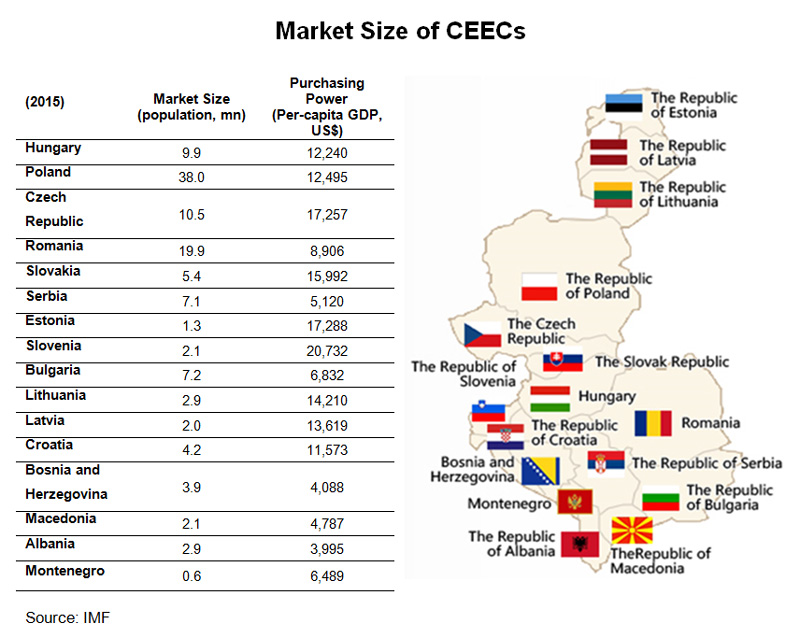

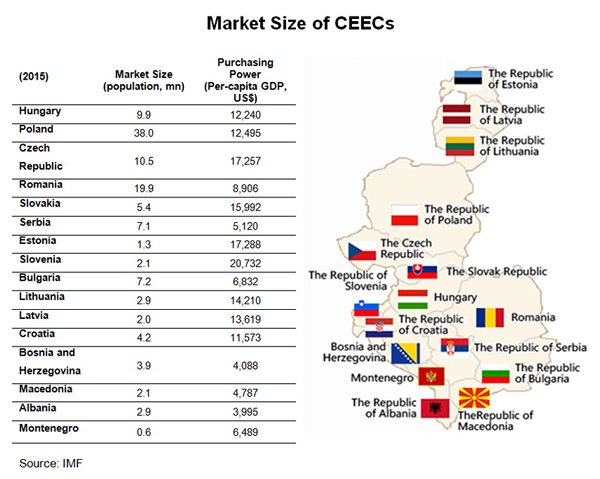

In 2011, China revived its co-operation with a group of 16 Central and Eastern European countries (CEECs), namely Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia and Slovenia. In 2012, the first meeting at a heads of government level was held in Warsaw, marking the official launch of the 16+1 format or mechanism under which China provides preferential financing to support investment projects that use Chinese inputs such as equipment “through business means”.

Since its establishment, the 16+1 format has not only been well-received by member countries, but is increasingly used as a leeway to allow cash-strapped CEECs to sidestep possible violations of EU restrictions on sovereign debt levels. Strengthening Sino-CEEC co-operation and connectivity is also conducive to the successful implementation of the BRI, which aims to facilitate and promote greater integration among the 60-plus countries along the Belt and Road. CEECs, providing a strategic link between Asia and West Europe, are vital to the success of the BRI.

Sino-CEEC Investment and Trade Continue to Blossom

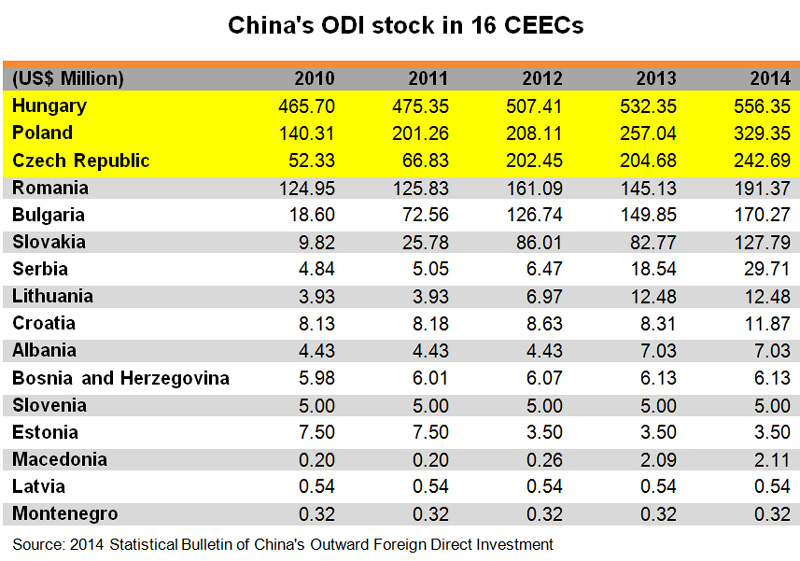

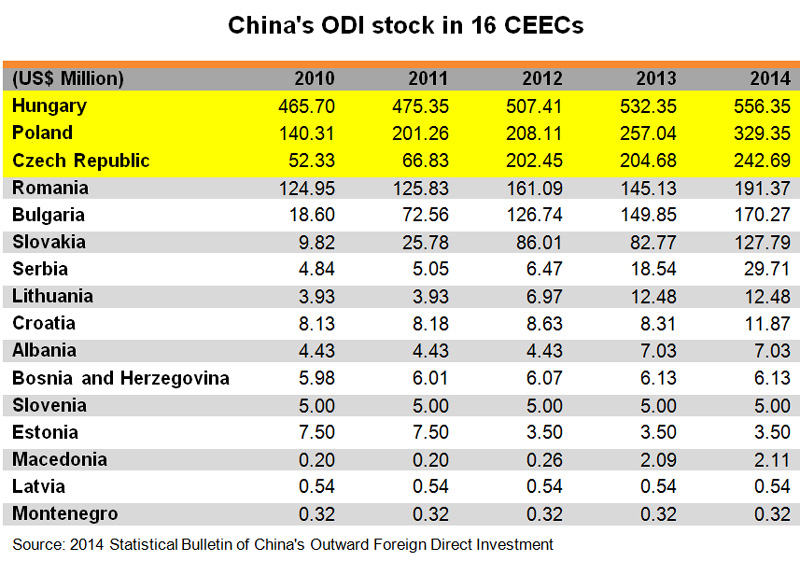

Banking on good Sino-CEEC relations and China’s implementation of a “going out” strategy at the turn of the century, Chinese investors have been investing in projects across the CEECs for some time. China’s outbound direct investment (ODI) in CEECs has been flourishing, while bilateral trade has also blossomed.

In the five years ending 2014, China’s ODI to CEECs grew by nearly 100% from US$853 million to US$1.7 billion. Among the 16 CEECs, three countries – namely Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic – accounted for more than two-thirds of the total, followed by Romania, Bulgaria and Slovakia, which together accounted for another 30%.

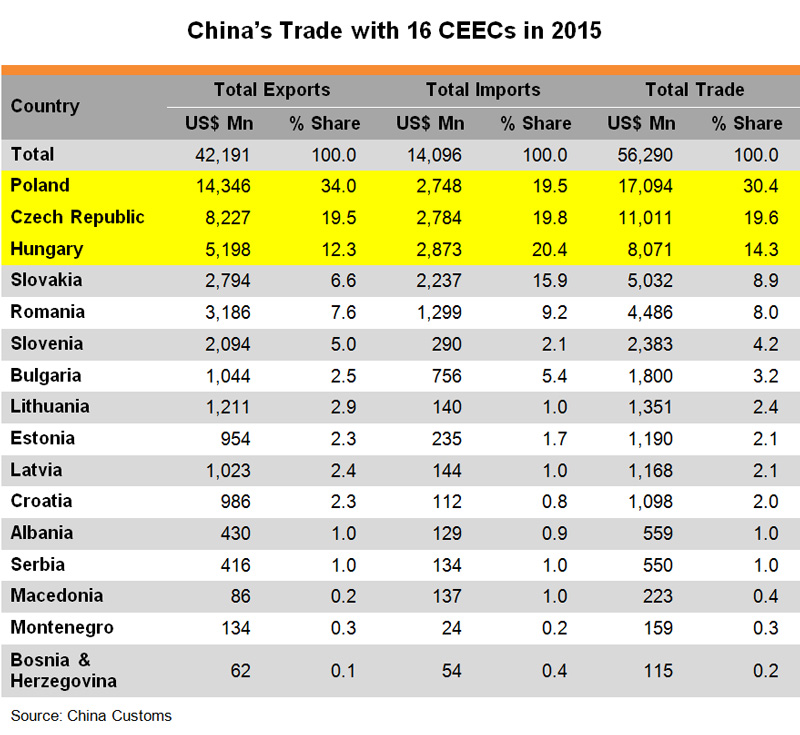

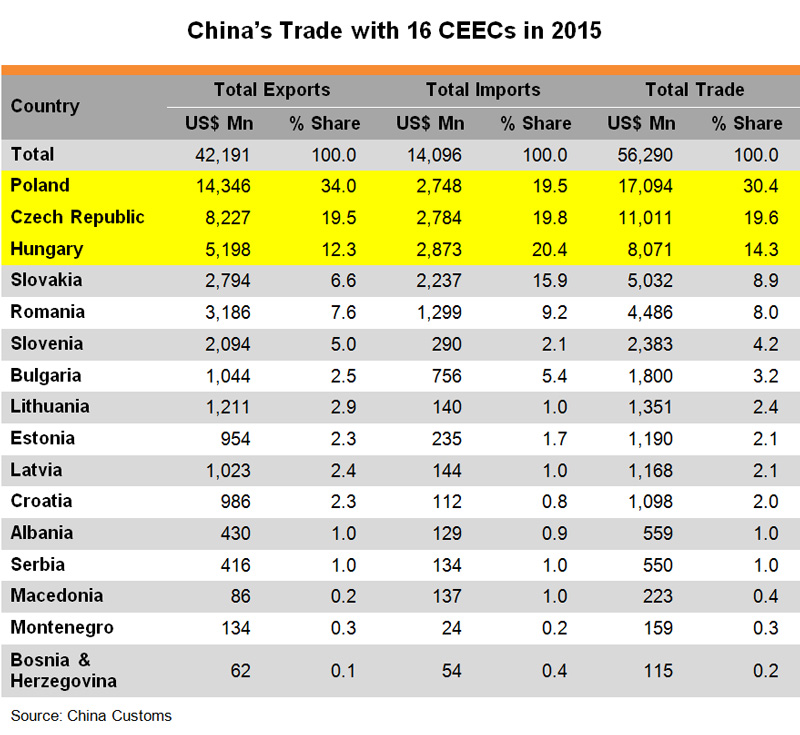

Trade between China and CEECs has remained unbalanced, however. In 2015, China’s exports were nearly twice the size of its imports from the 16 countries. This huge trade imbalance has provided a rallying cry for a new development model featuring enhanced connectivity with greater investment in infrastructure such as railroads, highways, tunnels, bridges, power plants, electric grids, industrial and logistic parks, seaports and airports.

In fact, there is already a balancing trend in Sino-CEEC trade, due mainly to an increase in demand for products such as metals, minerals, chemicals and food and beverages from CEECs. Between 2011 and 2015, China’s trade with 16 CEECs grew by a mere 6.4% from US$52.9 billion to US$56.3 billion. The country’s exports to CEECs increased in that period by only 5.0% but imports from the 16 countries saw a 10.5% expansion. Similar to the pattern seen in China’s ODI to CEECs, Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary were China’s top three trading partners among the 16 CEECs, accounting for more than 64% of all Sino-CEEC trade in 2015.

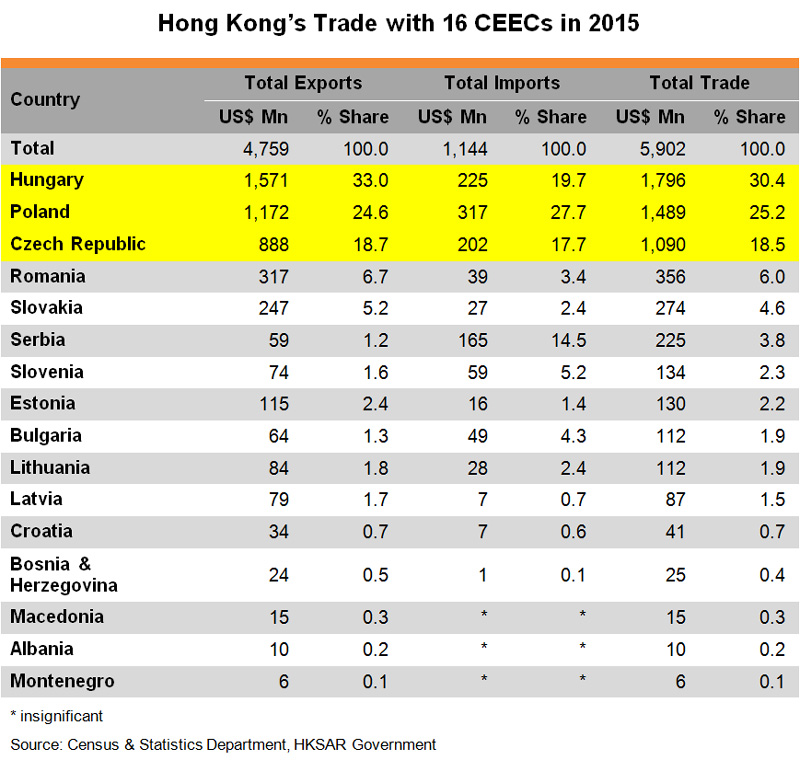

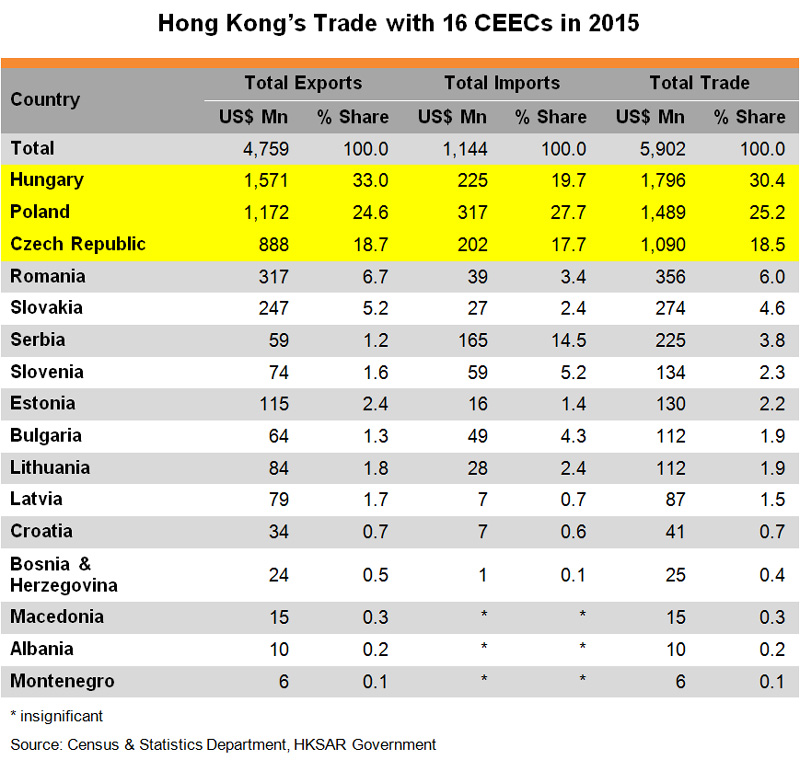

Though Hong Kong’s investment in the 16 CEECs is far from significant, its trade pattern is consistent with Sino-CEEC trade overall, with Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic accounting for nearly 75% of Hong Kong’s total trade with the 16 CEECs in 2015. Boasting a similar year-on-year growth of 24% in the first half of 2016, compared to the 13% regional average, Hungary and Poland are not only sizeable markets among the CEECs, but fast-growing export destinations for Hong Kong traders.

Looking ahead, better alignment of the 16+1 format with the BRI is expected to provide new opportunities to widen and deepen trade and investment co-operation between China and the CEECs. Moving from being export destinations to becoming investment partners in production, technology, finance and infrastructure development, CEECs are likely to see new trade patterns with China, involving higher value-added goods and services with higher technology content.

While different good and services may experience different fortunes in the CEECs, electronics – Hong Kong’s largest merchandise export earner – has fared well in the region. This is especially the case in countries where electronics manufacturing outsourcing clusters are becoming increasingly prominent in the face of rising production costs in other more distant production bases and in light of a greater need for proximity to key markets and better inventory management.

To this end, Hungary has been specialising in the production of transport vehicles since Soviet times, and boasts a long history of auto parts and electronics manufacturing. Hungary is the largest electronics producer among the CEECs, representing some 30% of the region’s total electronics output. Meanwhile, the Czech Republic is often regarded as the most successful Central and Eastern European country in terms of attracting foreign investment, thanks to its strong automotive cluster. For its part, Poland has the largest domestic market and ranks high in terms of manufacturing and automation.

Examples of BRI in Action in the CEECs

While most, if not all, of the CEECs are supporters of the BRI, some have shown greater participation than others. For instance, Poland, with its well-developed industrial market and logistical importance (it is estimated that 25% of all road transport in Europe is operated by Polish companies) has not only established a strategic partnership with China but is also a founding member of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) – the only CEEC joining the bank so far.

As an important conduit linking Asia and Western Europe in the BRI, in 2013 a high-speed railway started operating from Chengdu, the provincial capital of Sichuan province, in Southwest China, to Łódź, in Poland. The freight train takes only 10-12 days to ship goods from China to Poland, twice as fast as sea transport. Goods arriving in Łódź can then be transported to warehouses or customers in London, Paris, Berlin and Rome via Europe’s rail and road networks.

So far, railway lines for container trains have opened up in 16 Chinese mainland cities, heading to 12 European cities including many CEECs such as Łódź in Poland, Pardubice in the Czech Republic and Košice in Slovakia. Last year, Sino-European freight trains made a total of 815 trips, representing a year-on-year increase of 165%.

To better enhance co-operation between companies from both countries, Poland started offering consular services in Chengdu, while the Łódź government has also set up an office in the city. Such cooperation at sub-national levels has been institutionalised and increasingly offers a best-practice way forward in Sino-CEEC relations.

Meanwhile, Hungary – the first European country to sign a memorandum of understanding (MoU) on BRI co-operation with the Chinese mainland – has also signed deals to build a high-speed rail line between Budapest, its capital, and Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. With the line expected to be completed in 2017, the 85% Chinese-financed project will shorten the travel time between the two capitals from eight hours to three.

As an important country in the Balkan Peninsula, Serbia became China’s first strategic partner among the CEECs, in 2009. This favorable bilateral relationship is very much focused on economic co-operation under the BRI. China’s landmark projects in Serbia include the “Mihailo Pupin” Bridge on the Danube River in Belgrade, the construction of sections of the Corridor 11 highway, and the expansion of coal mines near the “Kostolac” thermal power plant.

The further extension of the Budapest-Belgrade high-speed rail line to Skopje, the capital of Macedonia, and to Athens, the capital of Greece, will give China-bound freight trains another alternative to gain access to the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas. To achieve better synergy, China’s state-owned shipping giant Cosco has recently acquired a majority stake in the Piraeus Port Authority, which complements the 35-year concession to operate Piers II and III at Piraeus port it acquired in 2009.

As the closest port in the Northern Mediterranean to the Suez Canal, Piraeus is not only one of the largest ports in the Mediterranean, but a strategic trans-shipment hub for Asian exports to Europe. China’s exports could reach Germany, for example, seven to 11 days earlier thanks to the abovementioned high-speed rail connection.

Under discussion or pending implementation are Chinese plans to invest on the construction and upgrading of port facilities in the Baltic, Adriatic, and Black Seas, with a focus on production capacity cooperation among ports and industrial and logistic parks along the coastal areas.

Hong Kong’s Unique Role in Sino-CEEC Economic Co-operation under the BRI

A new development model characterised by enhanced connectivity and greater multilateral investment will likely take Sino-CEEC economic co-operation to a higher level. The balancing trend in Sino-CEEC trade, plus the CEECs’ ongoing improvements to industrial capacity and logistical accessibility are highly conducive to the successful implementation of BRI.

Investment opportunities linked to the BRI can include cooperation in logistics along and beyond the Eurasian landbridge which directly connects Asia and Europe. Maritime finance, infrastructure bidding, project management and financing are all highly sought-after by project owners looking for competitive funding/co-operation options and Asian investors looking for more lucrative investment opportunities under Europe’s low interest-rate environment.

With about 60% of Chinese ODI being directed to, or channelled through, Hong Kong, the city, as a regional financial centre in Asia, will continue to be the bridgehead for Chinese mainland enterprises exploring “going out” through investing in greenfield schemes and joint investment projects. These may include smart cities/factories incorporating digital processes that use the Internet of Things (IoT) and Big Data, or conducting mergers and acquisitions (M&As) to reinvigorate companies, or even whole industries. Hong Kong is therefore ideally placed to help enterprises from CEECs look for investment partners from Asia, especially the Chinese mainland.

Possessing definite advantages and extensive experience in helping Chinese mainland enterprises make overseas investments, Hong Kong can play a pivotal role in the expected surge in Sino-European trade and Chinese ODI to CEECs under both the 16+1 format and the BRI, which aims to help companies co-ordinate their global supply chains.

Simultaneously, Hong Kong’s extensive link to other parts of Asia and privileged free-port status, coupled with the presence of cost-effective multimodal logistics options and professional services providers, offer CEECs a wealth of opportunities to make inroads into the burgeoning Asian market. Hong Kong’s position will be further strengthened as the Second Eurasian Land Bridge takes shape and new railway routes start operating.

Viewing Hong Kong as an ideal platform and super-connector to promote their products in mainland China and other markets in Asia, more and more companies from CEECs are using trade fairs and conferences in the city to reach out to Asian buyers and partners. For instance, Poland, as the regional leader in food exports to the Chinese mainland, has run a national pavilion at HKTDC Food Expo since 2013, occupying almost 300 square metres in 2016. This trend is expected to strengthen as companies from CEECs pay more and more attention to Asia due to European markets’ lack of growth drivers such as a sizeable youth population and growing incomes.